Abstract

Air pollution has been linked to increased incidence of diabetes. Recently, we showed that ozone (O3) induces glucose intolerance, and increases serum leptin and epinephrine in Brown Norway rats. In this study, we hypothesized that O3 exposure will cause systemic changes in metabolic homeostasis and that serum metabolomic and liver transcriptomic profiling will provide mechanistic insights. In the first experiment, male Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats were exposed to filtered air (FA) or O3 at 0.25, 0.50, or 1.0 ppm, 6 h/day for two days to establish concentration-related effects on glucose tolerance and lung injury. In a second experiment, rats were exposed to FA or 1.0 ppm O3, 6 h/day for either one or two consecutive days, and systemic metabolic responses were determined immediately after or 18 h post-exposure. O3 increased serum glucose and leptin on day 1. Glucose intolerance persisted through two days of exposure but reversed 18 h-post second exposure. O3 increased circulating metabolites of glycolysis, long-chain free fatty acids, branched-chain amino acids and cholesterol, while 1,5-anhydroglucitol, bile acids and metabolites of TCA cycle were decreased, indicating impaired glycemic control, proteolysis and lipolysis. Liver gene expression increased for markers of glycolysis, TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis, and decreased for markers of steroid and fat biosynthesis. Genes involved in apoptosis and mitochondrial function were also impacted by O3. In conclusion, short-term O3 exposure induces global metabolic derangement involving glucose, lipid, and amino acid metabolism, typical of a stress–response. It remains to be examined if these alterations contribute to insulin resistance upon chronic exposure.

Keywords: Air pollution, Ozone, Metabolic syndrome, Serum metabolomic, Stress response

Introduction

The incidence of metabolic syndrome is steadily increasing worldwide, resulting in higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Ford et al., 2002). The common clinical components that comprise metabolic syndrome include, but are not limited to, abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), prothrombotic state, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance (Ford et al., 2002; Grundy et al., 2004). Conventional etiologies, including sedentary lifestyle, diet-related obesity and genetics have been implicated as the major contributors to insulin resistance and the development of metabolic syndrome (Grundy et al., 2004). Most recently, air pollution, such as particulate matter (PM), has also been linked to the development of metabolic syndrome, and may serve as an effect modifier for the epidemiological associations between environmental factors and increased rate of cardiovascular diseases (Chen and Schwartz, 2008). A number of recent epidemiological and experimental studies have shown that chronic inhalation of airborne PM may increase an individual’s risk for acquiring type 2 diabetes by creating a pro-inflammatory state, insulin resistance, and/or obesity (Brook et al., 2008; Rajagopalan and Brook, 2012; Liu et al., 2013). A number of mechanistic pathways have been proposed where lung injury/inflammation initiates systemic inflammation, which is postulated to play a central role in inhaled pollutant-induced insulin resistance, but the evidence remains insufficient (Shoelson et al., 2006; O’Neill et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2011; Rajagopalan and Brook, 2012). Similar to PM, the ubiquitous air pollutant ozone (O3) has been associated with adverse pulmonary and cardiovascular health effects, such as lung injury/inflammation, decreased lung function and heart rate variability in animals and humans (Watkinson et al., 2001; Hollingsworth et al., 2007; Ciencewicki et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Farraj et al., 2012; Wagner et al., 2014). However, the likely contribution of O3 to metabolic disorder and extra-pulmonary effects has yet to be systematically investigated.

Exposure to O3 has also been shown to induce cardiovascular functional changes through modulation of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates sympathetic and parasympathetic balance (Farraj et al., 2012; Gordon et al., 2014). More specifically, acute O3 exposure has been shown to stimulate lung vagal C-fibers through transient receptor potential member A1 (TRPA-1) receptors that lead to activation of neural stress-responsive regions in the central nervous system where lung afferents of vagus nerves terminate (Taylor-Clark and Undem, 2010; Gackiere et al., 2011). Stress-mediated hypothalamus pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis activation is well known to modulate a variety of physiological processes including thermoregulation, immune elicitation, hormonal disposition, and systemic metabolic alterations (Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). One study has recently shown that acute O3 exposure increased serum corticosterone in rats (Thomson et al., 2013), which is a marker of HPA axis activation. Recently, we have shown that O3 induced glucose intolerance and increased serum leptin and epinephrine in Brown Norway (BN) rats, in addition to inducing hypothermia and bradycardia during exposure (Bass et al., 2013; Gordon et al., 2014). Observed increases in serum epinephrine and corticosterone during acute pollutant exposure suggest a potential involvement of sympathetic and/or HPA-associated neurohumoral factors. However, a detailed characterization of O3-induced metabolic impairment and involvement of neurohumoral intermediates has not been reported. This could aid in identifying potential mechanisms of O3-induced systemic metabolic effects.

The objective of this study was to utilize serum metabolomic and liver transcriptomic techniques together with metabolic hormonal assessment to gain insight into the characteristics and potential mechanisms of metabolic alterations during O3-induced hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance. The serum metabolomic approach used in this study is able to detect quantifiable metabolites in the serum released from biochemical processes in various tissues critical for metabolic homeostasis (Barnes et al., 2014). The detection of metabolites can provide insight regarding organs being affected by O3 exposure. Liver being the major organ for control and maintenance of metabolic processes, the assessment of liver transcriptional changes could provide mechanistic insights into its role in O3 systemic metabolic response. We hypothesized that O3-induced hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance will be associated with broad scale systemic metabolic impairment, and that the use of serum metabolomic together with liver transcriptomic approaches will provide insights into 1) the mechanisms by which O3 perturbs metabolic processes, and 2) the potential contribution of O3 to long-term metabolic alterations.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male, 10 week old, healthy Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats (250– 300 g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories Inc. (Raleigh, NC). Rats were housed (2/cage) in polycarbonate cages containing beta chip bedding in an isolated animal room in an animal facility maintained at 21 ± 1 °C, 50 ± 5% relative humidity and held to a 12 h light/dark cycle. The animal facility is approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). All animals received standard (5001) Purina pellet rat chow (Brentwood, MO) and water ad libitum unless otherwise stated. Animal procedures were approved by the U.S. EPA NHEERL Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; Permit Number: 13-02-003 and 16-03-003). Animals were treated humanely and all efforts were made for alleviation of suffering.

O3 generation and animal exposures

O3 was produced from oxygen by a silent arc discharge generator (OREC, Phoenix, AZ), and its entry into the Rochester style “Hinners” chambers was controlled by mass flow controllers. The O3 concentrations in the chambers were recorded continuously by photometric O3 analyzers (API Model 400). Chamber temperature and relative humidity were measured continuously. Mean chamber air temperature and relative humidity were 23.3 °C (74 °F) and 46%, respectively. In the concentration-response study, rats were randomized by body weight into four exposure groups (n = 6/group) to make sure each exposure group had the same overall average body weight. Similarly, in the time-course study, rats were randomized by body weight into six groups (n = 8/group) for two exposure conditions and each time point. In the concentration-response study, WKY rats were exposed to either filtered air (FA) or O3 (0.25, 0.50, or 1.0 ppm), 6 h/day for two consecutive days and sacrificed 18 h after day 2. In the subsequent time-course experiment, three groups of WKY rats were used. 1) The first group was either exposed to FA or 1.0 ppm of O3 for 6 h/day for one day (1 d–0 h), 2) a second group was exposed 6 h/day for two consecutive days (2 d–0 h), and 3) a third group was allowed an 18 h recovery, following two consecutive days of O3 exposure (2 d–18 h)

Glucose tolerance testing (GTT)

All rats that underwent GTT were fasted for 8–10 h in cage or during exposure prior to the assessment of blood glucose concentrations. For rats that were allowed an 18 h recovery period, food was removed for 10 h (overnight; 10 pm to 8 am) before GTT. Baseline blood glucose concentrations were measured by pricking the distal surface of rats’ tails using a sterile needle to obtain ~1 µl of blood. A Bayer Contour glucometer was used to determine blood glucose levels using test strips, which require 0.6 µL whole blood. After the first measurement, rats were given an intraperitoneal (I.P.) injection of glucose, 2 g/kg/10 mL (20% d-glucose; 10 ml/kg). Measurement with the glucometer was repeated every 30 min over the course of 2 h. In the concentration–response study, all animals underwent GTT 4 days prior to O3 exposure, immediately following O3 on day 1 and immediately following O3 on day 2. For the time-course study, rats assigned to the 18 h recovery group were used for GTT. These rats underwent GTT one day before O3 exposure, immediately following O3 exposure on day 1, immediately following O3 exposure on day 2, and also after an 18 h recovery period following two days of O3 exposure. In addition, rats assigned to the 2 d–0 h time point underwent GTT immediately following one day of FA or O3 exposure. No GTT was performed on the 1 d–0 h group where tissue and serum collection were performed immediately after exposure. The 2 d–0 h exposure group for tissue and serum collection did not undergo GTT on the 2nd day of O3 exposure.

Necropsy and sample collection

For the concentration–response study, all rats were necropsied 18 h after two consecutive days of FA or O3 exposure. For the time-course experiment, one group of rats (n = 16), which did not undergo GTT, were necropsied immediately after the first day of exposure (1 d–0 h). The 2nd group of rats (n = 16) was necropsied immediately after the second day of O3 exposure (2 d–0 h). The recovery group (n = 16) was necropsied 18 h after the second day of exposure (2 d–18 h). In each study, rats were fasted for 8–10 h before necropsy regardless of fasting associated with GTT. Rats were weighed and anesthetized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (Virbac AH, Inc., Fort Worth, TX; 50–100 mg/kg, i.p.). Blood samples were collected through an abdominal aortic puncture directly into serum separator vaccutainers without coagulant for serum preparation. Tubes were centrifuged at 3500 ×g for 10 min and aliquots of serum were stored at −80 °C until analysis. In the concentration–response study, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed through tracheal tubing using Ca2+-and Mg2+-free phosphate buffer saline, 37 °C at 28 mL total lung capacity/kg rat weight. Aliquots of BAL fluid were used to determine total cell counts with a Z1 Coulter Counter (Coulter, Inc., Miami, FL) and cell differentials were performed on cytospin slides stained with Diff-quick as previously described (Bass et al., 2013). The cell-free BAL fluid was used to analyze albumin, as previously described (Bass et al., 2013). In the time-course experiment, in addition to collecting serum at each time point, liver tissues were collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA analysis.

Serum analysis

Serum samples collected from rats were analyzed for insulin, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and leptin using rat-specific electrochemiluminescence assays (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD) via manufacturer’s instructions. Total cholesterol was measured in serum samples using kits from TECO Diagnostics (Anaheim, CA), while HDL-C and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were measured with kits from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Middletown, VA). Both types of kits were modified for use on the Konelab Arena 30 system (Thermo LabSystems, Espoo, Finland).

Metabolomic analysis

Serum global metabolomic profiling was performed by Metabolon Inc. (Durham, NC). Detailed methods are described in previous publications (Evans et al., 2009; Dehaven et al., 2010; Reitman et al., 2011). Frozen serum samples from time-course study for 1 d–0 h and 2d–0 h time points (n = 7–8/group) were used for this analysis.

Sample accessioning

Each sample received was accessioned into the Metabolon laboratory information management system (LIMS) and was assigned a unique identifier that was associated with the original source identifier only. This identifier was used to track all sample handling, tasks, results, etc. All aliquots of any sample were automatically assigned their own unique identifiers by the LIMS when a new task was created; the relationship of these samples is also tracked. All samples were maintained at −80 °C until processed.

Sample preparation

Samples were prepared using the automated MicroLab STAR® system from Hamilton Company. A recovery standard was added prior to the first step in the extraction process for QC purposes. Sample preparation was conducted using aqueous methanol extraction process to remove the protein fraction while allowing maximum recovery of small molecules. The resulting extract was divided into four fractions: one for analysis by Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectroscopy (UPLC/MS/MS) (positive mode), one for UPLC/MS/MS (negative mode), one for Gas chromatography/Mass Spectroscopy (GC/MS), and one for backup. Samples were placed briefly on a TurboVap® (Zymark) to remove the organic solvent. Each sample was then frozen and dried under vacuum. Samples were then prepared for the appropriate instrument, either UPLC/MS/MS or GC/MS.

UPLC/MS/MS

The LC/MS portion of the platform was based on a Waters ACQUITY ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) and a Thermo-Finnigan linear trap quadrupole (LTQ) mass spectrometer, which consisted of an electrospray ionization (ESI) source and linear ion-trap (LIT) mass analyzer. The sample extract was dried then reconstituted in acidic or basic LC-compatible solvents, each of which contained 8 or more injection standards at fixed concentrations to ensure injection and chromatographic consistency. One aliquot was analyzed using acidic positive ion optimized conditions and the other using basic negative ion optimized conditions in two independent injections using separate dedicated columns. Extracts reconstituted in acidic conditions were gradient eluted using water and methanol containing 0.1% formic acid, while the basic extracts, which also used water/methanol, contained 6.5 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The MS analysis alternated between MS and data-dependent MS2 scans using dynamic exclusion. Raw data files are archived and extracted as described below.

GC/MS

The samples destined for GC/MS analysis were re-dried under vacuum desiccation for a minimum of 24 h prior to being derivatized under dried nitrogen using bistrimethyl-silyl-trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA). The GC column was 5% phenyl and the temperature ramp was from 40 °C to 300 °C in a 16 min period. Samples were analyzed on a Thermo-Finnigan Trace DSQ fast-scanning single-quadrupole mass spectrometer using electron impact ionization. The instrument was tuned and calibrated for mass resolution and mass accuracy on a daily basis. The information output from the raw data files was automatically extracted as discussed below.

Quality assurance (QA)/quality control (QC)

For QA/QC purposes, additional samples were included with each day’s analysis. These samples included extracts of a pool of well-characterized human plasma, extracts of a pool created from a small aliquot of the experimental samples, and process blanks. QC samples were spaced evenly among the injections and all experimental samples were randomly distributed throughout the run. A selection of QC compounds was added to every sample for chromatographic alignment, including those under test. These compounds were carefully chosen so as not to interfere with the measurement of the endogenous compounds.

Metabolomic data extraction and compound identification

Raw data was extracted, peak-identified and QC processed using Metabolon’s hardware and software. Metabolite quantification was based on area under the curve. These systems are built on a web-service platform utilizing Microsoft’s. NET technologies, which run on high-performance application servers and fiber-channel storage arrays in clusters to provide active failover and load-balancing. Compounds were identified by comparison to library entries of purified standards or recurrent unknown entities. Metabolon maintains a library based on authenticated standards that contains the retention time/index (RI), mass to charge ratio (m/z), and chromatographic data (including MS/MS spectral data) on all molecules present in the library. Furthermore, biochemical identifications are based on three criteria: retention index within a narrow RI window of the proposed identification, nominal mass match to the library ±0.2 amu, and the MS/MS forward and reverse scores between the experimental data and authentic standards. The MS/MS scores are based on a comparison of the ions present in the experimental spectrum to the ions present in the library spectrum. While there may be similarities between these molecules based on one of these factors, the use of all three data points can be utilized to distinguish and differentiate biochemicals. More than 2400 commercially available purified standard compounds have been acquired and registered into LIMS for distribution to both the LC and GC platforms for determination of their analytical characteristics.

Statistical analysis of metabolomic data

Missing values (if any) are assumed to be below the level of detection. However, biochemicals that were detected in all samples from one or more groups but not in samples from other groups were assumed to be near the lower limit of detection in the groups in which they were not detected. In this case, the lowest detected level of these biochemicals was imputed for samples in which that biochemical was not detected. Following log transformation and imputation with minimum observed values for each compound, Welch’s two-sample t-test was used to identify biochemicals that differed significantly between experimental groups. Pathways were assigned for each metabolite, allowing examination of overrepresented pathways. Significant (p < 0.05) pathway enrichment output (cumulative hypergeometric distribution) was assessed for each of the selected contrasts (1 d–0 h; 2 d–0 h and 2d–18 h) using MetaboSync, version 1.0 (Metabolon, Inc. RTP, NC) to determine the metabolic processes impacted by O3.

Gene array

Liver tissue samples from FA or 1 ppm O3-exposed rats (n = 5–6/group) for all three time points from the time-course study were used for this analysis. Total liver RNA was isolated from ~20 mg tissue with a commercially available RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) using silica gel membrane purification. Liver RNA was resuspended in 30 µl of RNAse-free water. RNAse inhibitor was added and RNA yield was determined spectrophotometrically on a NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). RNA integrity was assessed by the RNA 6000 LabChip® kit using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). We examined global gene expression changes using the Affymetrix platform (RG-230 PM Array strip). Biotin-labeled cRNA was produced from total RNA using an Affymetrix IVT-express labeling kit (cat# 901229). Total cRNA was then quantified using a Nano-Drop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and evaluated for quality on a 2100 Bioanalyzer. Fragmented cRNA were also evaluated for quality using 2100 Bioanalyzer. Following overnight hybridization at 45 °C to Affymetrix RG-230 PM array strip in AccuBlock Digital Dry Baths (Labnet International Inc.), the arrays were washed and stained using an Affymetrix GeneAtlas fluidics station as recommended by the manufacturer. Arrays were scanned on an Affymetrix Model GeneAtlas scanner. After scanning, raw data (Affymetrix.cel files) were obtained using Affymetrix Command Console Operating Software. This software also provided summary reports by which array QA metrics were evaluated including average background, average signal, and 3′/5′ expression ratios for spike-in control GAPDH.

Normalization and determination of differentially expressed genes

The Affymetrix GeneAtlas array data for each sample was normalized by Affymetrix Expression Console software using the plier algorithm with perfect match only probes. The resulting expression table was downloaded from Affymetrix Expression Console software into a text file. Statistical contrasts were calculated at each time point for O3 vs. the FA control. Each contrast was computed on a text file containing all assayed genes as rows and only the contrast samples as columns by a Bayes t-test using R. Subsequently, a multiple test correction using the Benjamin–Hochberg method with an alpha of 0.05 was applied to the Bayes t-test output in Excel. To support subsequent analysis, the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from the three time-point contrasts were consolidated into an O3 DEG expression table.

Functional gene list preparation

The DEG list for each time point was also submitted to the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v6.7 for determination of significant Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways using a modified Fisher Exact test with a p-value cutoff of 0.05. Functional gene lists were generated by NetAffx queries at the Affymetrix website (www.affymetrix.com). The query terms were “apoptosis”, “diabetes”, “gluconeogenesis”, “glycolysis”, “mitochondria”, “steroid metabolism”, “tricarboxylic acid cycle”, “unfolded protein response” and “cytokines”. The eight lists were exported separately from NetAffx as text files. For each gene list, Affymetrix probeset IDs were used to select the corresponding gene from the O3 DEG expression table to build an expression table that only contains the genes for a given function that were also O3 DEGs. Hierarchical clustering was computed for each functional gene list using Cluster 3.0 (de Hoon et al., 2004) and the clusters were displayed using Java Treeview (Saldanha, 2004). Three functional probeset lists based on queries of “steroid receptor”, “insulin receptor” or “fatty acid” were obtained from NetAffx. Each of these lists was compared to the list of DEGs for the 1 d–0 h time point to identify DEGs in each of the three functional categories. Each functional list was processed separately by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) to produce a direct relationship graph. The graph constructed from the Ingenuity knowledgebase depicts some of the biological relationships among the probe sets on the list. The microarray data are publically available through Gene Expression Omnibus (accession # GSE59329).

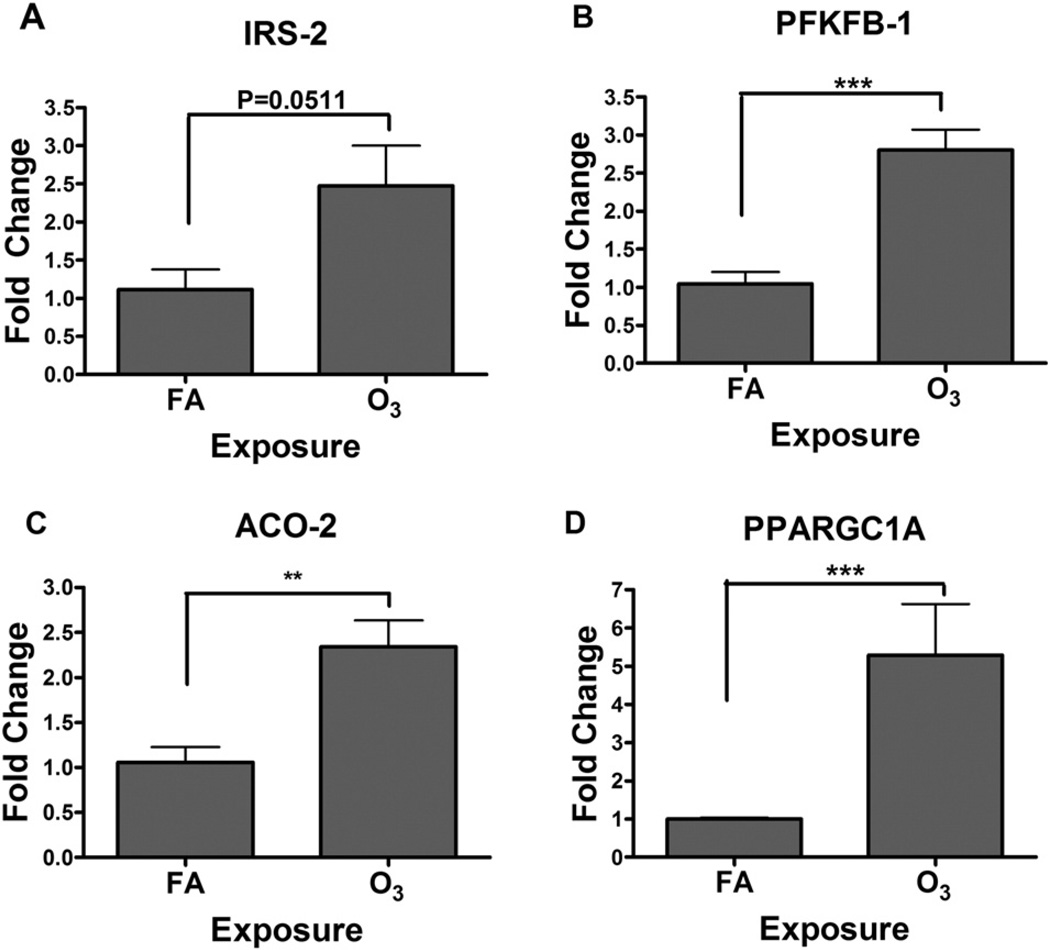

Real time PCR confirmation of gene array findings

We selected 4 genes increased in expression from the gene array (insulin receptor substrate-2, IRS-2; 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 1, PFKFB1; aconitase-2, Aco-2; and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma c1a, Ppargc1a) and a control transcript (β-actin) to determine the validity of gene array findings. RT-PCR for RNA from FA or O3-exposed rat livers at 1 d–0 h time point was conducted on an ABI Prism 7900 HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described previously (Bass et al., 2013). Primers were purchased from ABI as inventoried TaqMan Gene Expression Assays, each containing a 6-carboxy-fluorescein (FAM dye) label at the 5′ end. Data were analyzed using ABI sequence detection software (SDS version 2.2). For each PCR plate, cycle threshold (cT) was set to an order of magnitude above background. For each individual sample, target gene cT was normalized to a control gene cT (β-actin) to account for variability in the starting RNA amount. Expression of exposure group was quantified as fold difference over FA control.

General statistical analysis

Graphpad prism 4.03 software was used for statistical analysis of GTT and biomarker data. Dose response study GTT was analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) where each time blood glucose measurement was independently assessed. The two independent variables were day and dose. One-way ANOVA was used for data analysis of neutrophils and albumin in the BAL fluid. The time-course study GTT was analyzed by two-way repeated measures MANOVA (multivariate ANOVA). The two independent variables were day and dose. The time course study biomarker measurements were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test. Pair-wise comparisons were performed as subtests of the overall ANOVA. The nominal Type I error rate (α) was set at 0.05. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Results

O3 induces pulmonary injury and inflammation in a concentration-dependent manner

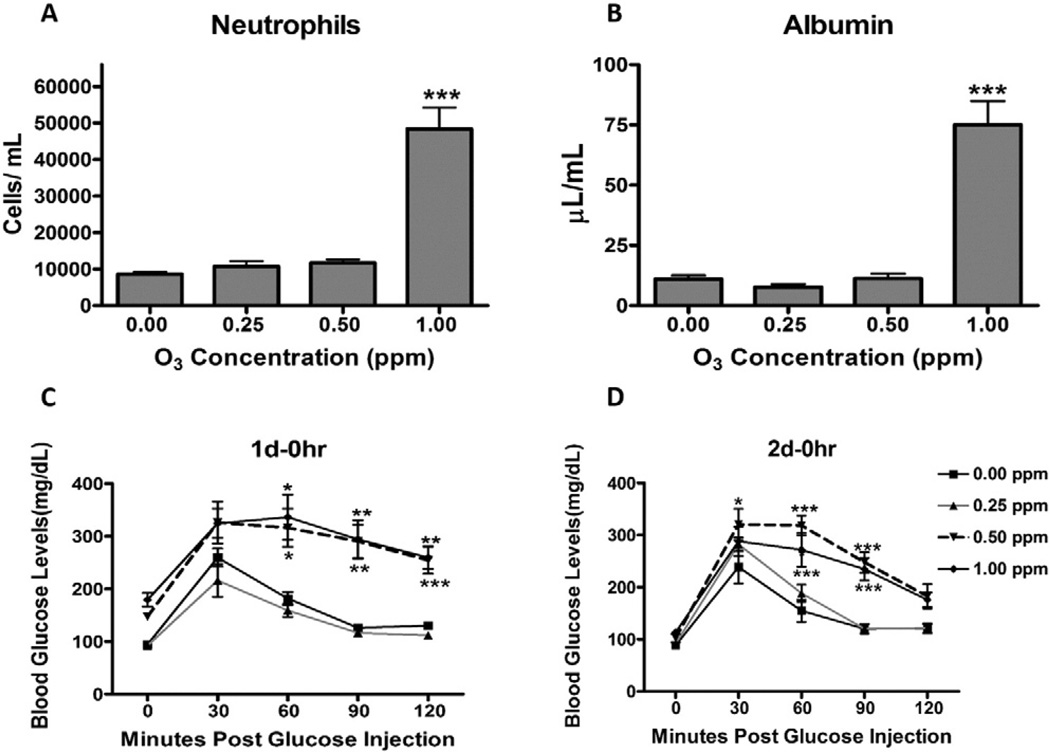

Although O3 is well studied for its potential to induce lung injury in many experimental settings, we wanted to determine the concentration-dependent cellular responses and inflammation in our experimental model to better correlate these changes with systemic metabolic alterations. Therefore, we first confirmed O3-induced pulmonary cellular responses in WKY rats by examining the BAL fluid for increases in the lung vascular leakage of albumin and neutrophilic inflammation at 18 h post two consecutive days of O3 exposure. Inflammation and cellular responses have been shown to peak on the second day of O3 exposure (van Bree et al., 2001). The concentration response analysis showed that 1.0 ppm O3 increased the number of neutrophils in the BAL fluid (Fig. 1A). Albumin, a lung protein leakage marker that exists at lower levels in the normal lung, was also elevated at 1.0 ppm O3 (Fig. 1B). These changes were not evident in rats exposed to 0.5 or 0.25 ppm O3.

Fig. 1.

O3-induced cellular and inflammatory responses in the lung are associated with hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance in WKY rats. Rats were exposed to FA or O3 (0.25, 0.5 or 1.0 ppm) for 6 h/day for two consecutive days. Immediately after day 1 (1 d–0 h) and day 2 (2 d–0 h) of exposure GTT was performed. Rats were necropsied 18 h after day 2 exposure (2 d–18 h) and BAL fluid was analyzed for lung toxicity markers. (A) Neutrophils, as a marker of inflammation. (B) Albumin, as an indicator of vascular protein leakage. (C) Blood glucose at baseline and during GTT in rats exposed to FA or O3 (1 d–0 h). (D) Blood glucose at baseline and during GTT in rats exposed to FA or O3 (2 d–0 h). The values in the bar graphs are displayed as mean ± SE of n = 6/exposure group. The GTT curve shows mean value ± SE of n = 6/group with repeated measures over 2 h. The 0 min time point shows fasting glucose levels in each group. * Indicates significant difference from respective FA-exposed groups at a given time (* = p < .05, ** = p < .01, *** = p < .001).

O3 exposure induces concentration- and time-dependent hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance

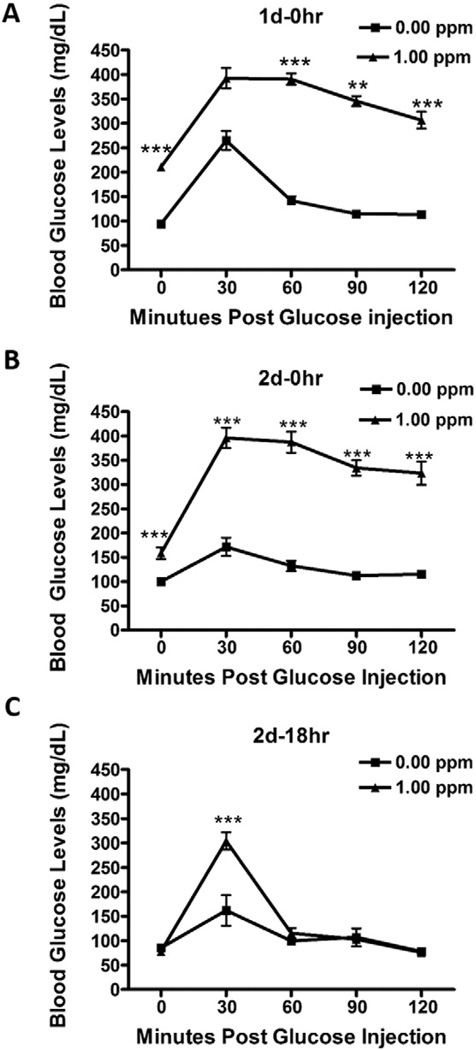

GTT in the concentration–response study was conducted to determine whether O3-induced cellular and inflammatory lung responses were associated with prior changes in blood glucose regulation. In comparison to the FA group, O3-exposed rats at 0.5 and 1.0 ppm on day 1 displayed marked fasting hyperglycemia (0 min time point; Fig. 1C). By contrast, the 2 d–0 h O3 exposure group illustrated diminished fasting hyperglycemia (Fig. 1D). Both the 0.5 and 1.0 ppm experimental groups exhibited glucose intolerance when examined immediately after O3 exposure on day 1 (Fig. 1C) and day 2 (Fig. 1D). O3 at 0.25 ppm caused neither hyperglycemia nor glucose intolerance (Figs. 1C and D). GTT was also performed in the time-course study where exposure was to FA or 1.0 ppm O3. As noted in the concentration–response study (Fig. 1C), O3 at 1.0 ppm induced hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance when examined immediately after a 6 h exposure (1 d–0 h; Fig. 2A). Like O3 exposure on day 1, hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance persisted on day 2 of exposure (Fig. 2B). O3-induced hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance were largely reversed after 18 h in the recovery group (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Acute O3 exposure induces reversible hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance. GTT was performed in rats exposed to FA or 1.0 ppm of O3 immediately after first day of 6 h O3 (1 d–0 h) (A); immediately after second day of 6 h O3 (2 d–0 h) (B); and at 18 h after second day of 6 h O3 exposure (2 d–18 h) (C; recovery group). Each value represents mean ± SE of n = 8/group. *Indicates significant difference from FA exposed rats for a given time point (** = p < .01, *** = p < .001).

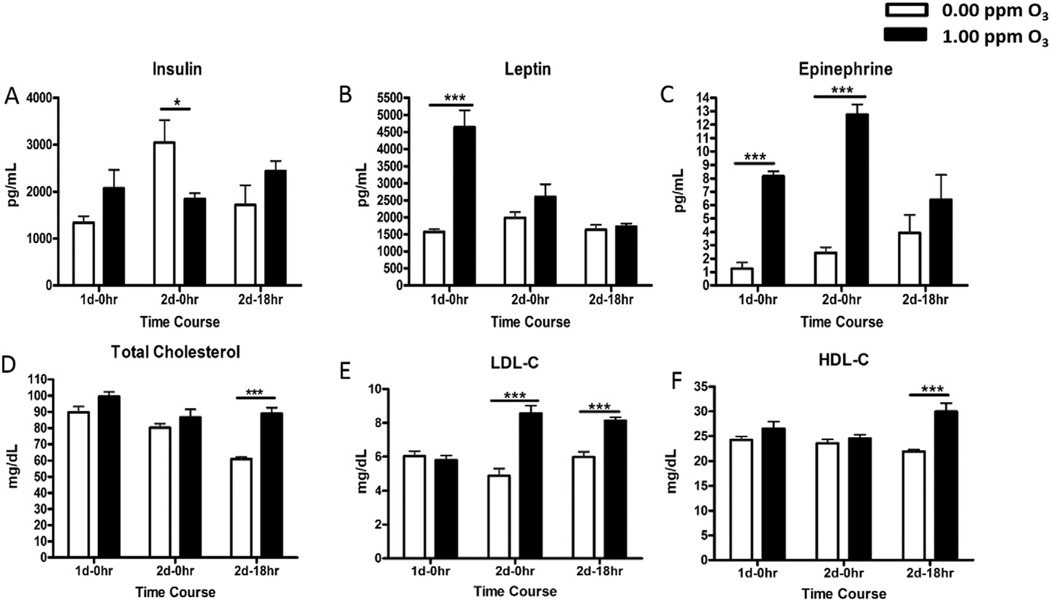

O3 exposure alters the serum metabolic hormones and lipids

To determine the potential cause of hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance, we assessed the serum levels of metabolic hormones and cytokines through electroimmunochemiluminescence and colorimetric ELISA techniques. Variability was noted in baseline (FA control) levels of insulin between three time points, where FA-exposed rats after 2 d–0 h had high levels of insulin relative to the other two groups. This increase in insulin could relate to the sustained stimulation of its release in response to the injection of a high dose of glucose immediately following the day 1 of FA or O3 exposure for performing GTT. When compared to time-matched FA group, serum insulin levels were lower in O3-exposed rats at 2 d–0 h time point (Fig. 3A). Serum leptin, a satiety hormone, increased after day 1 (1 d–0 h) of O3 exposure, but not on day 2 (2 d–0 h) or following an 18 h of recovery (2 d–18h)(Fig. 3B). Serum IL-6 did not change after O3 exposure at any time point (Fig. 3C). There was a significant diurnal variation in cholesterol levels of FA-exposed rats such that rats necropsied in the afternoon times for 1 d–0 h and 2 d–0 h had higher levels than rats necropsied in the morning at 2 d–18 h time point. O3 exposure resulted in elevated serum total cholesterol and HDL-C at 2 d–18 h time point (Figs. 3D and F). The levels of LDL-C were increased on day 2 (2 d–0 h and 2 d–18 h) after O3 exposure (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Acute O3 exposure alters circulating mediators, metabolic hormones and lipids in rats. Metabolic hormones and cholesterols were measured in the serum of FA and O3 exposed rats at various time points (1 d–0 h, 2 d–0 h, 2 d–18 h). Each value indicated in the bar graphs represents mean ± SE (n = 6–8/group). *Indicates significant difference from time-matched FA exposed rats (* = p < .05, ** = p < .01, *** = p < .001).

Metabolomic analysis

We conducted metabolomic analysis of serum samples from FA or 1.0 ppm O3-exposed rats at 1 d–0 h and 2 d–0 h to gain understanding of the nature of metabolic changes and potential involvement of multiple organs in homeostatic control of metabolic processes. Comparison of global biochemical profiles for rat serum revealed several key metabolic differences between O3-exposed rats vs. FA control. The metabolomic analysis identified strong effects of O3 exposure on metabolites that reflect changes in central energy metabolism. Of 313 named biochemicals identified in the serum, 81 metabolites were significantly increased in O3-exposed rats and 48 decreased at 1 d–0 h, while 71 metabolites were increased and 80 were decreased at 2 d–0 h. Pathway analysis identified a number of pathways that were significantly altered after O3 exposure. Those included lysine catabolism, branch chain amino acids (BCAA) metabolism, protein degradation, urea cycle, sphingolipids metabolism, fatty acid synthesis, primary and secondary bile acid metabolism and glutathione metabolism at 1 d–0 h. Many of these pathways also remained changed at 2 d–0 h, in addition to alteration in beta-oxidation pathway. A detailed analysis of metabolic processes affected based on individual metabolites impacted by O3 is given below.

Metabolomic analysis: O3 impairs glucose homeostasis through perturbation of glycolytic pathways

The metabolomic analysis confirmed hyperglycemia at 1 d–0 h following O3 exposure (Table 1), as evident during GTT. In addition, the metabolite 1,5-anhydroglucitol, a biomarker inversely related to long-term glycemic control, was markedly decreased in O3-exposed animals at both time points (Table 1). Fructose levels were also increased at 1 d–0 h but not at 2 d–0 h. The glycolysis end-product pyruvate was increased on day 1 of O3 exposure while the anaerobic glycolytic metabolite, lactate, was significantly decreased at day 2 in O3 exposed animals (Table 1). Several tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates (citrate, α-ketoglutarate, fumarate and malate) were less abundant in the serum samples of O3-exposed rats especially on day 2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolomic analysis: O3-induced changes in serum metabolites for glucose and amino acid metabolism.

| Fold change |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological processes | Metabolite | O3 1 d/ | p-Value | O3 2 d/ | p-Value |

| FA 1 d | FA 2 d | ||||

| Glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, pyruvate metabolism | Glucose | 1.47 | 0.0000 | 1.07 | 0.2801 |

| Fructose | 1.64 | 0.0168 | 1.16 | 0.5933 | |

| 1,5 androhydroglucitol | 0.77 | 0.0073 | 0.75 | 0.004 | |

| Pyruvate | 1.87 | 0.0011 | 0.86 | 0.2283 | |

| Lactate | 1.1 | 0.3613 | 0.72 | 0.0029 | |

| Kreb cycle | Citrate | 1.07 | 0.5455 | 0.83 | 0.0778 |

| Alpha-ketoglutarate | 0.7 | 0.0067 | 0.67 | 0.0048 | |

| Succinate | 0.88 | 0.481 | 0.91 | 0.3771 | |

| Fumarate | 1.08 | 0.9269 | 0.66 | 0.0177 | |

| Malate | 0.78 | 0.1529 | 0.73 | 0.0414 | |

| Tryptophan metabolism | Kinurenate | 3.13 | 0.0004 | 2.11 | 0.0137 |

| Kinurenine | 1.63 | 0.0001 | 1.23 | 0.0468 | |

| Amino acid metabolism | 3-Methylhistidine | 1.03 | 0.7168 | 1.22 | 0.0117 |

| N-acetyl-1-methylhistidine | 0.85 | 0.1509 | 1.60 | 0.0008 | |

| 3-methyl-2-oxobutyrate | 1.62 | 0.0001 | 1.46 | 0.0009 | |

| 3-methyl-2-oxovalerate | 1.84 | 0.0000 | 1.6 | 0.0001 | |

| Isoleucine | 1.47 | 0.0000 | 1.47 | 0.0000 | |

| Leucine | 1.57 | 0.0000 | 1.39 | 0.0001 | |

| Valine | 1.69 | 0.0000 | 1.49 | 0.0000 | |

| 4-methyl-2-oxopentanoate | 1.89 | 0.0000 | 1.59 | 0.0000 | |

| Beta-hydroxyisovalerate | 1.85 | 0.0005 | 1.78 | 0.0006 | |

| Beta-hydroxyisovalerate | 2.03 | 0.0000 | 1.53 | 0.0001 | |

| N-acetylleucine | 5.72 | 0.0000 | 1.36 | 0.1878 | |

| N-acetylvaline | 2.16 | 0.0000 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| N-acetylisoleucine | 5.79 | 0.0000 | 1.81 | 0.018 | |

| 3-hydroxyisobutyrate | 1.91 | 0.0000 | 1.4 | 0.0038 | |

| 4-methyl-2-oxopentanoate | 1.89 | 0.0000 | 1.59 | 0.0000 | |

| Alpha-hydroxyisovalerate | 2.06 | 0.0000 | 1.47 | 0.0071 | |

| Isobutyrylcarnitine | 1.2 | 0.1633 | 0.61 | 0.0011 | |

| 2-hydroxy-3-methylvalerate | 1.87 | 0.0000 | 1.34 | 0.0041 | |

| 2-methylbutyrylcarnitine (C5) | 1.31 | 0.0891 | 1.06 | 0.6531 | |

| Isovalerylcarnitine | 1.63 | 0.0029 | 1.26 | 0.0973 | |

| Urea | 1.24 | 0.0143 | 1.18 | 0.0398 | |

Table depicting O3-induced changes in circulating metabolites reflecting changes in glucose metabolism following 1 d or 2 d of FA or O3 exposure. Values indicate relative fold differences for each biochemical between O3 and FA samples at each time point (n = 6–7/group). Fold change >1 indicates increase, while fold change <1 indicates decrease. When p-value is < .05, the change is considered significant.

Metabolomic analysis: O3 exposure increases serum amino acids

A number of BCAA and their metabolites were increased in the serum following O3 exposure (Table 1). The data showed several signatures of altered protein and amino acid catabolism. Urea, generated to eliminate nitrogenous waste made from amino acid catabolism, was more abundant with O3 exposure. One muscle-specific protein catabolite (3-methylhistidine) and one possible muscle protein catabolite (N-acetyl-1-methylhistidine) were more abundant after 2 days of O3 exposure, suggesting their release from muscle (Table 1). Increases were observed in the BCAA themselves (leucine, valine and isoleucine) as well as several metabolites generated when BCAA are catabolized to enter the TCA cycle. Some of these metabolites (alpha-hydroxyisocaproate, alpha-hydroxyisovalerate and 2-hydroxy-3-methylvalerate) are typically present at low abundance unless dehydrogenase reactions are defective, or with mitochondrial dysfunction. Combined with the observed decrease in TCA cycle intermediates, these metabolite changes may reflect mitochondrial dysfunction.

Metabolomic analysis: O3 exposure increases serum free fatty acids (FAA) and cholesterol while decreasing bile acids

All detectable short- and long-chain FFA were noticeably more abundant in O3-exposed rats at both time points. These increases included essential, non-essential, saturated, polyunsaturated and hydroxy fatty acids ranging in length from C12 to C22, as well as, palmitoyl and stearoyl sphingomyelin (Table 2). Additionally, O3 exposure reduced mitochondrial β-oxidation metabolites (beta-hydroxybutyric acid, propionylcarnitine and butyrylcarnitine) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Metabolomic analysis: O3 exposure increases circulating FFA.

| Fold change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological processes | Metabolite | O3 1d | p-Value | O3 2d | p-Value |

| FA 1 d | FA 2 d | ||||

| Essential fatty acid | Linoleate (18:2n6) | 1.57 | 0.0034 | 2.14 | 0.0000 |

| Linolenate [alpha or gamma; (18:3n3 or 6)] | 1.63 | 0.0107 | 2.17 | 0.0001 | |

| Dihomo-linolenate (20:3n3 or n6) | 1.67 | 0.0014 | 1.13 | 0.296 | |

| Eicosapentaenoate (EPA; 20:5n3) | 2.12 | 0.0000 | 1.29 | 0.0426 | |

| Docosapentaenoate (n3 DPA; 22:5n3) | 2.02 | 0.0000 | 1.3 | 0.0268 | |

| Docosapentaenoate (n6 DPA; 22:5n6) | 2.22 | 0.0000 | 1.7 | 0.0001 | |

| Docosahexaenoate (DHA; 22:6n3) | 1.93 | 0.0000 | 1.59 | 0.0001 | |

| Long chain fatty acid | Myristate (14:0) | 1.31 | 0.0087 | 1.49 | 0.0001 |

| Myristoleate (14:1n5) | 1.33 | 0.0358 | 1.84 | 0.0001 | |

| Pentadecanoate (15:0) | 1.37 | 0.0048 | 1.39 | 0.0018 | |

| Palmitate (16:0) | 1.59 | 0.0009 | 1.8 | 0.0000 | |

| Palmitoleate (16:1n7) | 1.51 | 0.0417 | 2.47 | 0.0001 | |

| Margarate (17:0) | 1.51 | 0.0016 | 1.68 | 0.0001 | |

| 10-heptadecenoate (17:1n7) | 1.31 | 0.0119 | 1.47 | 0.0003 | |

| Stearate (18:0) | 1.33 | 0.0034 | 1.36 | 0.001 | |

| Oleate (18:1n9) | 1.61 | 0.0069 | 2.38 | 0.0000 | |

| Cis-vaccenate (18:1n7) | 1.65 | 0.0091 | 1.46 | 0.027 | |

| Nonadecanoate (19:0) | 1.27 | 0.1076 | 1.38 | 0.0156 | |

| 10-nonadecenoate (19:1n9) | 1.4 | 0.1337 | 1.63 | 0.0077 | |

| Eicosenoate (20:1n9 or 11) | 1.29 | 0.0804 | 1.39 | 0.0227 | |

| Dihomo-linoleate (20:2n6) | 1.6 | 0.0021 | 1.45 | 0.0057 | |

| Mead acid (20:3n9) | 1.77 | 0.0003 | 1.51 | 0.0032 | |

| Arachidonate (20:4n6) | 1.22 | 0.0819 | 1.23 | 0.0474 | |

| Docosadienoate (22:2n6) | 1.42 | 0.0077 | 1.07 | 0.5246 | |

| Adrenate (22:4n6) | 1.88 | 0.0001 | 1.26 | 0.0814 | |

| Fatty acid, monohydroxy | 3-hydroxypropanoate | 0.99 | 0.9762 | 0.73 | 0.0091 |

| 3-hydroxyoctanoate | 0.93 | 0.7825 | 0.99 | 0.8814 | |

| 2-hydroxystearate | 1.3 | 0.0029 | 1.26 | 0.0066 | |

| 2-hydroxypalmitate | 1.34 | 0.0007 | 1.31 | 0.0007 | |

| Fatty acid and BCAA metabolism | Propionylcarnitine | 0.82 | 0.1495 | 0.64 | 0.008 |

| Butyrylcarnitine | 0.72 | 0.0168 | 0.54 | 0.0001 | |

| Butyrylglycine | 0.87 | 0.168 | 0.94 | 0.4452 | |

Table depicting O3-induced changes incirculating FFA following1d or 2 d of FA or O3 exposure. Values indicate relative fold differences for each biochemical between O3 and FA samples at each time point (n = 6–7/group). Fold change >1 indicates increase, while fold change <1 indicates decrease. When p-value is <.05, the change is considered significant.

Bile acids are synthesized in the liver from cholesterol, further metabolized by the gut microbiome, and released into the intestine to facilitate dietary fat absorption. In this study, several cholesterol and bile acid metabolites were changed by O3 exposure. Serum cholesterol was elevated, while virtually all serum bile acid metabolites were decreased in O3-exposed rats at both time points (Table 3). The observed increase in diet-derived phytosterols (fucosterol, beta-sitosterol and campesterol) suggests increased dietary absorption of cholesterols or decreased metabolism/excretion of cholesterol. While rats were not provided food during O3 exposure, the changes in circulating cholesterol and bile acids might be due to decreased metabolism and/or release in the circulation. The observed decreases in several bile acids and an intermediate in bile acid synthesis from cholesterol (7-hoca) suggest decreased bile acid production may contribute to elevated serum cholesterol (Table 3).

Table 3.

Metabolomic analysis: O3 exposure alters circulating metabolites indicative of impairment in cholesterol and bile acid metabolism.

| Biological processes | Metabolite | Fold change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3 1d | p-Value | O3 2d | p-Value | ||

| FA 1 d | FA 2 d | ||||

| Bile acid metabolism | Cholate | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.0019 |

| Glycocholate | 0.21 | 0.0061 | 0.18 | 0.001 | |

| Chenodeoxycholate | 0.27 | 0.0401 | 0.16 | 0.0062 | |

| Hyodeoxycholate | 0.32 | 0.003 | 0.62 | 0.1782 | |

| Taurodeoxycholate | 0.5 | 0.0279 | 1.81 | 0.1032 | |

| Glycodeoxycholate | 0.07 | 0.0042 | 0.16 | 0.0671 | |

| Glycochenodeoxycholate | 0.15 | 0.0219 | 0.08 | 0.0041 | |

| 6-Beta-hydroxylithocholate | 0.17 | 0.0005 | 0.45 | 0.1509 | |

| Beta-muricholate | 0.33 | 0.0251 | 0.3 | 0.0011 | |

| Hyocholate | 0.38 | 0.0974 | 0.33 | 0.011 | |

| Alpha-muricholate | 0.19 | 0.013 | 0.12 | 0.0006 | |

| Tauroursodeoxycholate | 0.46 | 0.0058 | 1.09 | 0.8176 | |

| Tauro-alpha-muricholate | 0.54 | 0.0222 | 0.89 | 0.6976 | |

| Taurohyodeoxycholic acid | 0.25 | 0.0011 | 1.14 | 0.5012 | |

| Monoacyl-glycerol | 1-Linoleoylglycerol (1-monolinolein) | 0.64 | 0.0009 | 0.54 | 0.0000 |

| 2-Linoleoylglycerol (2-monolinolein) | 0.64 | 0.0004 | 0.52 | 0.0000 | |

| 1-Arachidonylglycerol | 0.64 | 0.0065 | 0.79 | 0.0689 | |

| 2-Arachidonoyl glycerol | 0.67 | 0.0172 | 0.75 | 0.0496 | |

| Sphingolipid | Palmitoyl sphingomyelin | 1.57 | 0.0004 | 1.75 | 0.0000 |

| Stearoyl sphingomyelin | 2.73 | 0.0018 | 2.66 | 0.0002 | |

| Sterol/steroid | Cholesterol | 1.33 | 0.0003 | 1.27 | 0.0008 |

| Beta-sitosterol | 1.44 | 0.0003 | 1.1 | 0.2589 | |

| Campesterol | 1.31 | 0.0047 | 1.07 | 0.5349 | |

| Fucosterol | 1.43 | 0.0101 | 1.25 | 0.0895 | |

Table depicting O3-induced changes in circulating cholesterol and bile acid metabolites following 1 d or 2 d of FA or O3 exposure. Values indicate relative fold differences for each biochemical between O3 and FA samples at each time point (n = 6–7/group). Fold change >1 indicates increase, while fold change <1 indicates decrease. When p-value is <.05, the change is considered significant.

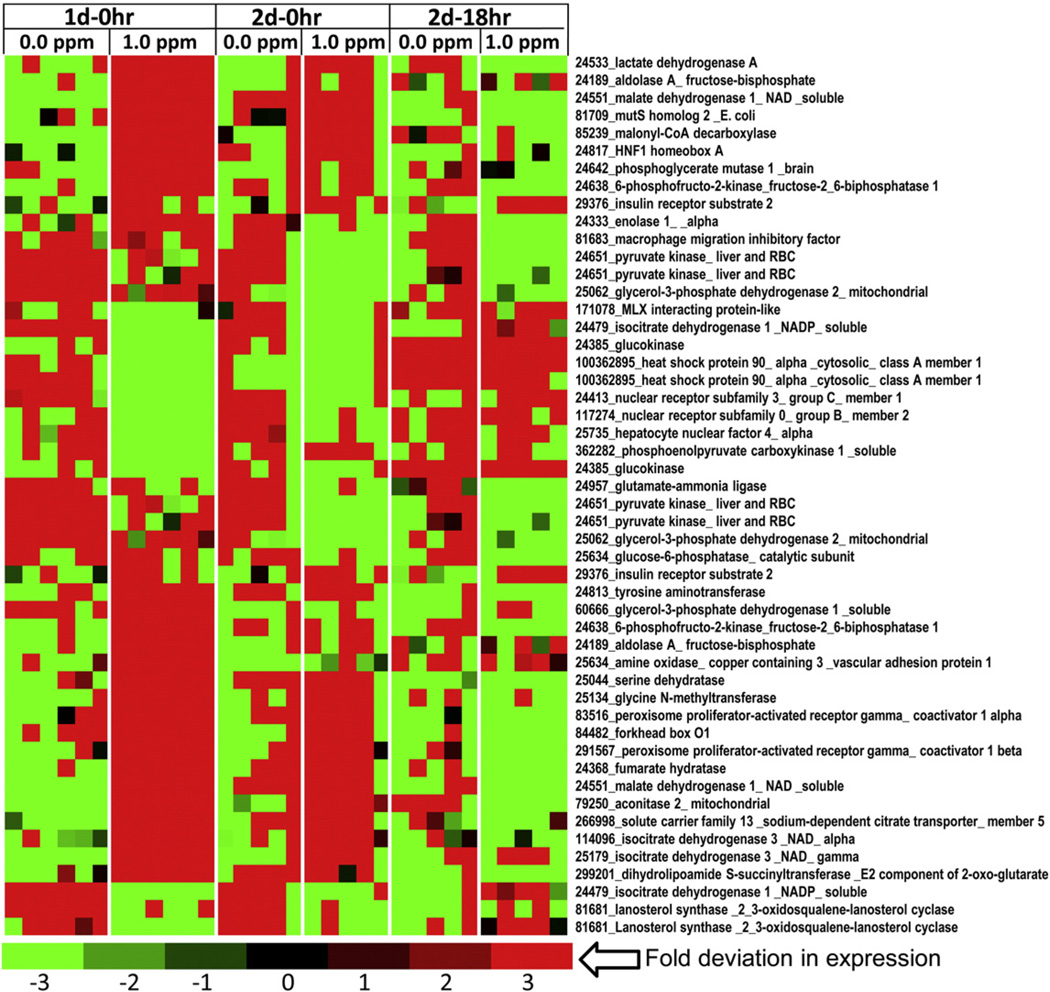

Liver transcriptomic profiling reveals its role in homeostatic control of O3-induced systemic metabolic alterations

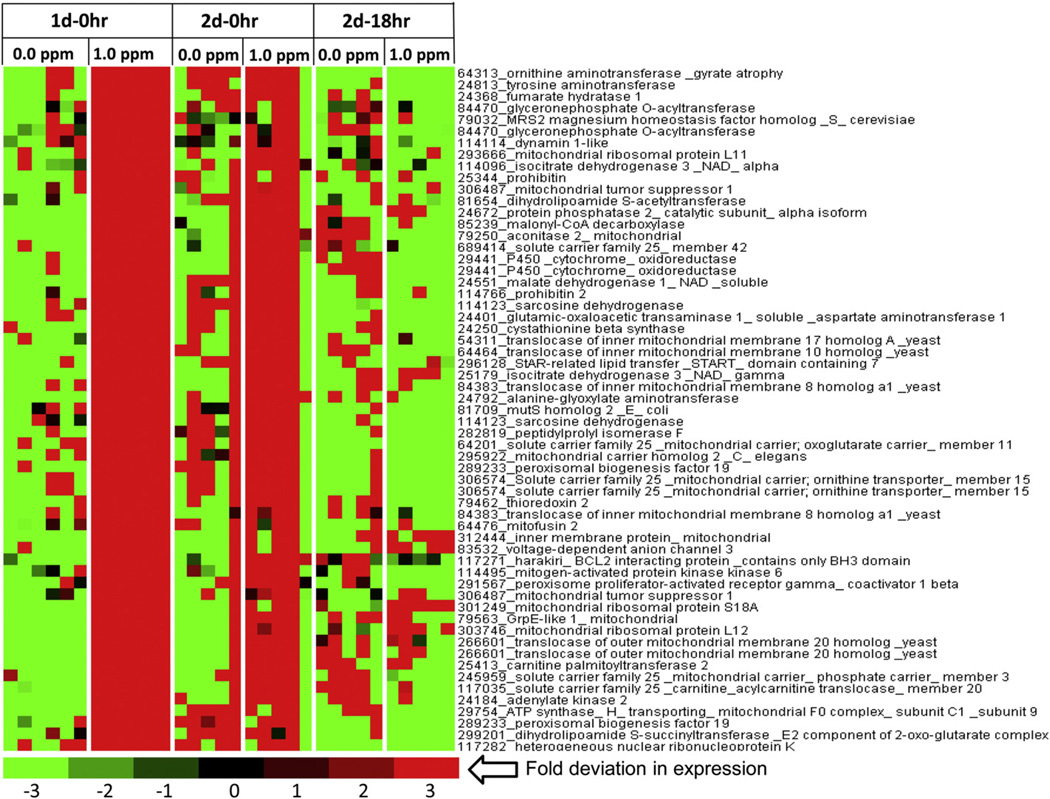

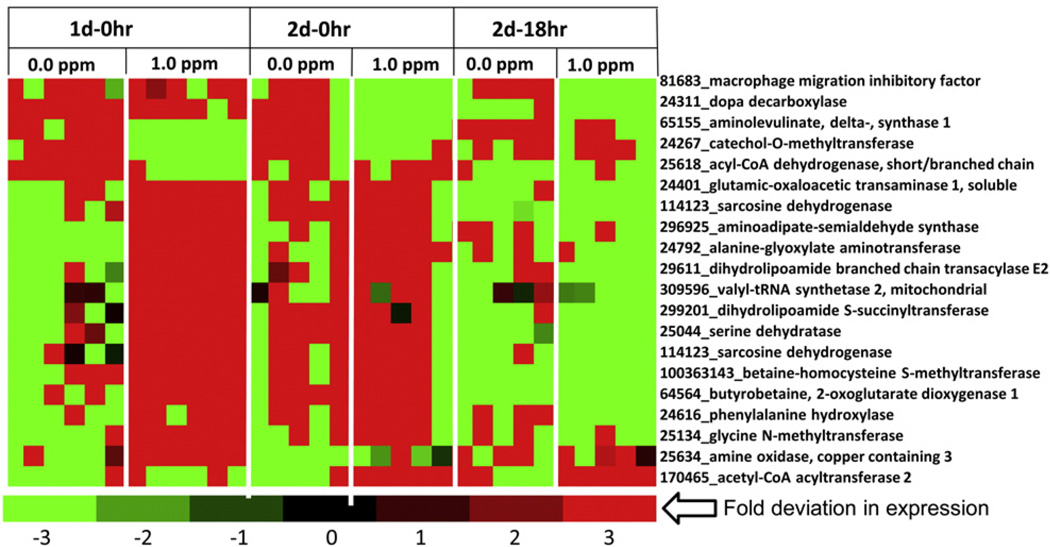

Because the liver is the primary organ that regulates glucose, amino acid, cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism, we conducted global gene expression profiling of liver to determine its role in systemic metabolic impairment induced byO3 exposure. Overall, the effect of O3 on the liver transcriptome was greatest at 1 d–0 h with reduction in number of genes affected at 2 d–0 h and 2 d–18 h. At 1 d–0 h, 2335 genes were found to be significantly different in O3-exposed rats compared to FA controls, while on 2 d–0 h there were only 72 genes and 2 d–18 h there were 247 genes differentially expressed. KEGG pathway analysis of liver DEGs at day 1 indicated that steroid biosynthesis, TCA cycle, and glyoxylate and decarboxylate metabolism pathways were significantly altered by O3. When genes associated with various metabolic processes, apoptosis, mitochondria, unfolded protein response and diabetes were separated from master DEGs list, probe sets assigned to each of this process represented 11–34% of the total probes on the array, suggesting widespread liver gene expression impact of O3 exposure implicating metabolic processes (Supplementary Information (SI) Table 1). The heatmaps of cytokine network showed inhibition of many genes with induction of some genes (SI Fig. 1A – C). Many genes belonging to apoptosis pathway were impacted by O3 exposure (SI Fig. 2A – F). Genes involved in steroid and fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling were of interest and showed that O3 impacted key regulatory genes involved in these processes (SI Fig. 3 and Fig. 4A – C).

Fig. 4.

Altered transcription levels of genes involved in glucose metabolism in the livers of O3-exposed rats. Functional gene lists were generated by NetAffx queries at the Affymetrix website (www.affymetrix.com) and identified from DEGs list based on the query terms, “glycolysis”, “tricarboxylic acid” cycle and “gluconeogenesis”. These genes were selected to prepare expression value tables for each sample. Genes were then median centered with average linkage, hierarchically clustered using Cluster 3.0 and displayed through Java Treeview. Red indicates genes that have high expression values across all groups, green indicates genes that have low expression values across all groups, and black indicates median expression. Note that this heat map is truncated to show important clusters affected by O3 exposure (n = 5–6/group).

O3 increased hepatic expression of numerous glycolytic genes including insulin receptor substrate-2, lactate dehydrogense A, aldolase A, phosphoglycerate mutase-1, enolase 1-alpha, pyruvate kinase, 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase-fuctose-2,6 bisphosphatase, and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-2 at 1 d–0 h and 2 d–0 h (Fig. 4), suggesting a central stimulation to increase glycolysis. However, the expression of glucokinase, an important enzyme for conversion of circulating glucose to glucose-6-phosphate, was decreased in O3-exposed rats. Interestingly, O3 exposure also increased the expression of some of the gluconeogenic genes, such as the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1-soluble, glucose-6-phosphatase, and phosphofructo-2-kinase-fuctose-2,6 bisphosphatase, which is a multi-functional protein that plays a role in gluconeogenesis, as well as, glycolysis. In addition, O3 increased expression of genes involved in amino acid metabolism that feed into gluconeogenesis. Those included glutamate-ammonia ligase, tyrosine aminotransferase, serine dehydratase, and glycine-N-methyltransferase (Fig. 4). O3 also elevated expression of genes encoding the TCA cycle enzymes such as fumarate hydratase, acontinase-2, and isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 NAD-alpha and gamma suggestive of enhanced energy expenditure in the liver.

Because many genes involved in glycolysis and TCA cycle were induced, we presumed that liver mitochondrial function might also be affected by O3 exposure. Many of the observed glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and TCA genes modified by acute O3 exposure were seen in heat maps generated for mitochondria gene cluster (Figs. 5A and B). These also included genes involved in steroid metabolism. Mitochondrial heat maps (Figs. 5A and B) showed that O3 decreased the expression of genes involved in cholesterol and steroid metabolism. These genes included farnesyl diphosphate synthase, ATP citrate lyases, and MLX interacting protein. Meanwhile, O3 increased the expression of genes involved in glycolytic and fatty acid catabolic processes, such as acyl CoA thioesterase 1, acyl CoA thioesterase 2, acyl CoA thioesterase 7, 3-hydroxybutarte dehydrogense type 1, and pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase catalytic subunit 2 (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, O3 increased expression of genes encoding enzymes involved in mitochondria biogenesis and homeostasis in the liver, such as the peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gamma, involved in liver homeostatic control. O3-exposed rats also showed increases in mitochondria apoptotic genes such as the Bcl-2 interacting protein containing the BH3 subunit and other genes involved in apoptotic pathways (Fig. 5B; SI Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

Acute O3 exposure modulates the expression of genes involved in liver mitochondrial function. Functional gene lists were generated by NetAffx queries at the Affymetrix website (www.affymetrix.com) and identified from DEGs list based on the query term, “mitochondrial genes”. Genes were then median centered with average linkage, hierarchically clustered using Cluster 3.0 and displayed through Java Treeview. (A) A cluster of mitochondria genes showing lower expression after O3 exposure relative to FA. (B) A cluster of genes showing higher expression in rats exposed to O3 relative to FA-exposed rats. Red indicates genes that have high expression values across all groups, green indicates genes that have low expression values across all groups, and black indicates median expression (n = 5–6/group).

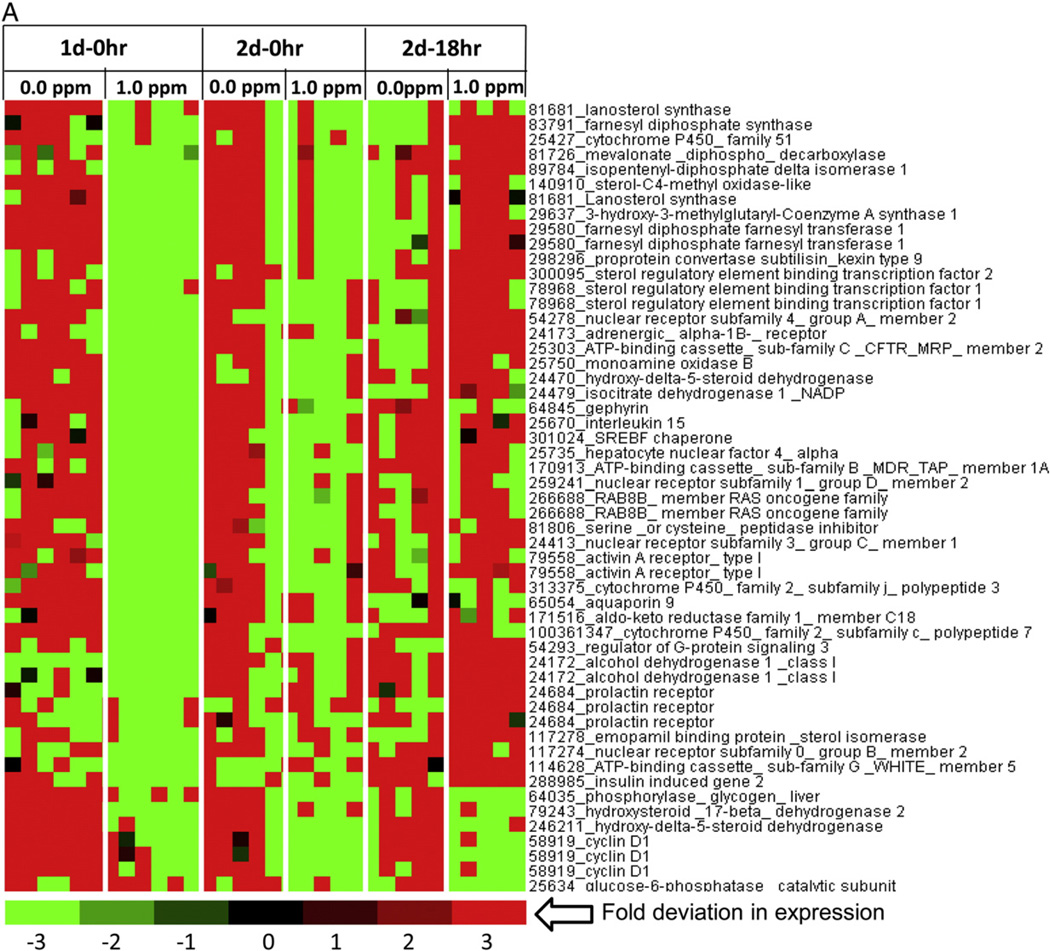

While metabolomics data indicated marked changes in FFA and steroid metabolism, DEGs belonging to these processes were separated from a master DEGs list of liver genes. Since these metabolic pathways operate in mitochondria, some of these genes were readily seen in the heat maps for mitochondrial genes. A heat map of steroid metabolism genes further confirmed that O3 exposure decreased expression of genes that encode enzymes necessary for cholesterol synthesis in the liver, including but not limited to, lanosterol synthase, farnesyl diphosphate synthase, mevalonate diphospho-decarboxylase, isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase, sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1/2, and more (Fig. 6A). In contrast, O3 increased the expression of genes that encode for the proteins arginase, argininosuccinate lyase, and argininosuccinate synthetase, which are essential for liver ammonia detoxifying processes and the progression of the urea cycle (Fig. 6B). O3-exposed rats also demonstrated higher expression of genes that encode for nuclear receptors, such as, estrogen, thyroid, and RAR-related orphan receptor A (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Modification of steroid metabolism genes in the livers of rats after O3 exposure. Functional gene lists were generated by NetAffx queries at the Affymetrix website (www.affymetrix.com) and identified from DEGs list based on the query term, “steroid metabolism genes”. Genes were then median centered with average linkage, hierarchically clustered using Cluster 3.0 and displayed through Java Treeview. (A) A cluster of steroid metabolism genes showing lower expression after O3 exposure relative to FA (B) A cluster of steroid metabolism genes showing higher expression in rats exposed to O3 relative to FA. Red indicates genes that have high expression values across all groups, green indicates genes that have low expression values across all groups, and black indicates median expression (n = 5–6/group).

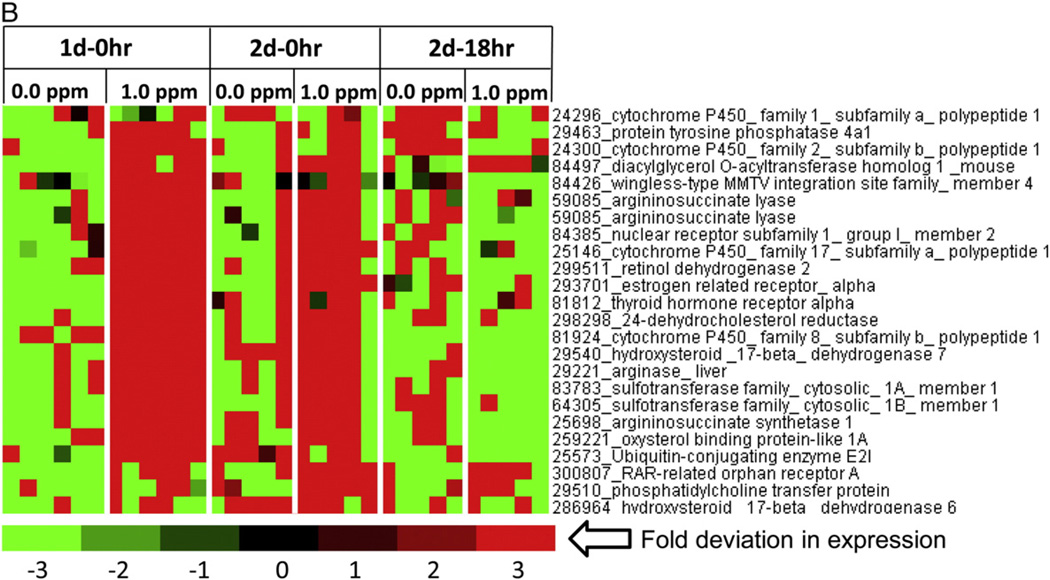

Since increases in circulating BCAA occurred likely due to increased muscle protein catabolism, we wanted to determine whether genes involved in liver amino acid metabolism responded to this systemic response. Some of the genes involved in the use of amino acids for gluconeogenesis providing precursors for TCA cycle were induced by O3, as indicated earlier. These gene included dihydrolipamide S-succinyltransferase, serine dehydratase, aminoadipate-semialdehyde synthase, butyrobetaine, 2-oxoglutarate dioxygenase 1 and more (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

O3 exposure alters expression of genes involved in amino acid metabolism in the liver. Functional gene lists were generated by NetAffx queries at the Affymetrix website (www.affymetrix.com ) and identified from DEGs list based on the query term, “amino acid metabolism”. Genes were then median centered with average linkage, hierarchically clustered using Cluster 3.0 and displayed through Java Treeview. Heat map of DEGs with significant O3 effect Red indicates genes that have high expression values across all groups, green indicates genes that have low expression values across all groups, and black indicates median expression (n = 5–6/group).

We confirmed the validity of the liver gene array findings using RT-PCR for four transcripts at 1 d–0 h time point (Fig. 8). All four transcripts that are important in metabolic regulation, including IRS-2, PFKFB1, Aco-2, and Ppargc1a, were found to be increased when expression was analyzed using RT-PCR, confirming that the array technique provided satisfactory results (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

O3-induced increases in expression of selected genes confirmed using RT-PCR. Total liver RNA from FA and O3-exposed rats(1 d–0 h) was used for RT-PCR (n= 6/group). The expression values were first normalized for individual rats using β-actin as a control transcript and then relative fold change from O3 was calculated using FA values. *Indicates significant difference from FA-exposed rats for a given time point (** = p < .01, *** = p < .001).

Discussion

Recent epidemiological and experimental studies have shown that O3 and ambient PM, in addition to causing respiratory effects in humans and animals, may also contribute to a number of systemic health outcomes such as neuronal, reproductive, cardiovascular and metabolic effects, including insulin resistance (Campbell, 2004; Thomson et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; Pedersen et al., 2014). The mechanisms of these systemic effects are poorly understood. We have recently shown that acute O3 exposure in BN rats induces glucose intolerance, leptinemia and catecholamine release generally observed during a stress response (Bass et al., 2013). O3 exposure has been shown to induce lung injury and inflammation (van Bree et al., 2001), activate stress responsive regions in the brain (Gackiere et al., 2011), and induce hypothermia and bradycardia (Gordon et al., 2014). In this study, our goal was to characterize the homeostatic metabolic response of the WKY rat to O3 exposure using serum metabolomic and liver transcriptomic approaches to better understand the potential mechanisms responsible for systemic metabolic alterations.

In WKY rats, O3-induced fasting hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance, and serum leptin increases that were much more pronounced than responses we recently reported in BN rats (Bass et al., 2013). These metabolic and hormonal changes were accompanied by rapid and reversible increases in serum protein degradation byproducts, FFA and cholesterol, depictive of a systemic metabolic response, and decreases in TCA cycle intermediates, which might relate to hypothermia observed in rats after an O3 exposure (Gordon et al., 2014). Liver gene expression changes were coherent with changes in serum metabolites and showed inhibition of genes involved in steroid biosynthesis but stimulation of genes involved in gluconeogenesis, glycolysis, β-oxidation and energy expenditure. O3-induced release of short- and long-chain FFA into the circulation, likely involving adipose lipolysis, was coincided with decreased expression of hepatic lipid biosynthesis genes. The concomitant increase in circulating cholesterol may be a result of reduced catabolism in the liver as a consequence of inhibition of bile acid synthesis evidenced by the decrease in circulating bile acid metabolites. Further, our data show increased flux of BCAA into the circulation, which corroborated with increased expression of hepatic enzymes that utilize precursor amino acids for gluconeogenesis. Overall,we show that these acute systemic effects of O3 exposure involve a broad scale derangement of glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism reflective of a sympathetic and HPA-mediated stress response. If and how this reversible derangement might relate to chronic development of metabolic disorders will require studies involving long-term exposures.

As observed in our study, O3-induced lung injury and inflammation peaks one day after an acute exposure (van Bree et al., 2001). We have shown that O3 initially induces acute hypothermia during exposure but this is followed by hyperthermia and lung inflammation the following day. The temporal pattern of metabolic changes seen in the present study suggests that neuronal response might be stimulated prior to inflammation. A number of animal studies have shown that O3 can induce neuroinflammation and activate catecholeminergic neurons likely through lung vagus afferents (Gackiere et al., 2011; Martínez-Lazcano et al., 2013). Activation of these central nervous system locations can stimulate sympathetic and HPA-mediated release of adrenal stress hormones in the systemic circulation, which can perturb metabolic functions involving glucose, lipids, and amino acids (Seematter et al., 2004). We have also observed an increase of epinephrine after an acute O3 exposure in BN rats (Bass et al., 2013). In addition, O3 has been shown to increase corticosteroidal activities in multiple tissues likely through activation of HPA-axis (Thomson et al., 2013). The systemic metabolic changes such as hyperglycemia, glucose-intolerance, lipidemia, and amino acid influx induced by O3 are similar to those induced during a neuronally-mediated stress response following an organ injury (Molina, 2005; Wang et al., 2007). Although stress-mediated metabolic disorder has been very well established, no prior air pollution studies have linked a stress response to subsequent systemic metabolic impairment.

Temporal differences were noted in O3-mediated hyperglycemia, leptinemia and glucose intolerance. Leptinemia was observed only on day 1, which coincided with fasting hyperglycemia, increased circulating pyruvate and 2-hydroxybutarate on day 1 and decreased lactate on day 2, while glucose intolerance persisted over both days. This may relate to a number of potential interactive mechanisms governing glucose intolerance and could explain the reversible nature of metabolic effects upon termination of O3 exposure. It is not clear what stimulates leptin release immediately after O3 exposure, which coincides with release of FFA on day 1 but not on day 2. The stimulation of sympathetic nerves is known to result in inhibition of leptin secretion (Sandoval and Davis, 2003), but the activation of HPA has been associated with its increase (Roubos et al., 2012). Leptin is made primarily in adipocytes and has major impact on metabolic and immune processes (Mainardi et al., 2013). Since adipose lipolysis is likely stimulated after O3 exposure, it is possible that the release of FFA into the circulation stimulates concomitant leptin release. However, leptin increase was not sustained on day 2 while FFA continued to be increased. Acute release of leptin from adipose tissue can directly signal the hypothalamus to mediate peripheral fat oxidation and suppress food intake (Roubos et al., 2012). It has been shown that increased leptin can inhibit the neurons co-expressing neuropeptide Y (NPY) and Agouti-related peptide (AgRP) in the arcuate nucleus in the medio-basal hypothalamus (Morton, 2007). Thus, leptin can contribute to the reduction of acute fasting hyperglycemia observed on day 2 of O3 exposure.

Enhanced expressions of some of the genes involved in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and glycolysis after O3 exposure are suggestive of the changes induced following a stress response (Raz et al., 1991; Dufour et al., 2009). The O3-induced increases in corticosterone (Thomson et al., 2013) may augment hepatic glucose production by stimulating glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. However, the increase in blood glucose is accompanied by increases in 2-hydroxybutarate on day 1 and decreases in 1,5-anhydroglucitol in serumat both time points, suggesting compromised glycemic control (Buse et al., 2003). Concomitantly, the glycolytic metabolite pyruvate accumulated only on day 1 with a slight reduction on day 2, suggesting that glycolysis does not progress into the TCA cycle at least in the early phase of O3 exposure in the tissues. In contrast, lactate decrease in the O3-exposed group on day 2 may indicate subsequent reduction of anaerobic glycolysis in the peripheral tissues that may coincide with the rebound effect on body temperature in rats following termination of exposure as previously noted (Gordon et al., 2014). O3 exposed rats showed reduced serum levels of TCA cycle and β-oxidation intermediates despite stimulation of genes in the liver. These changes suggest that the O3-induced metabolic response likely involves reduced energy expenditure byperipheral tissues, such as the muscle, while maintaining homeostatic activities in the liver.

O3 exposure decreased serum insulin levels despite glucose intolerance, particularly on day 2, suggesting that β-cells in the pancreas may be impacted. It has been shown that the autonomic nervous system can have inhibitory effects on insulin production and secretion into systemic circulation by islet β-cells (Bloom et al., 1978; Buijs et al., 2001; Kiba, 2004). Additionally, short-term leptin increases have also been observed to suppress β-cells’ insulin production through sympathetic activation in rodents (Park et al., 2010). It is possible that this is an adaptive mechanism involving short-term insulin resistance in the peripheral tissues in the midst of O3-induced stress to ensure adequate glucose supply to the brain and other organs actively involved in maintenance of homeostasis, such as the liver.

The release of FFA into the circulation from adipose lipolysis is one of the hallmark features of stress-induced metabolic alterations. O3-induced increases in circulating FFA could be due to sympathetic action on white adipocytes (Nonogaki, 2000). It is has been shown that catecholamines during a stress response stimulate lipolysis and the mobilization of FFA in adipose tissue through activation of the β-adrenergic receptors (Carey, 1998). β-adrenergic receptor activation results in stimulation of adenylyl cyclase, followed by increases in intracellular cAMP, leading to the degradation of triglycerides and shuttling of FFA into the systemic circulation (Carey, 1998). In addition, activation of the HPA axis can also cause increased release of FFA from adipose tissues (Carey, 1998). Increased circulating FFA are known to induce insulin resistance by increasing serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and halting insulin-mediated glucose uptake (Schulman and Zhou, 2009), which may explain O3-induced glucose intolerance.

O3-induced increase in circulating cholesterol further supports the contribution of sympathetic or HPA axis activation (Kunihara and Oshima, 1983). Despite, rats being fasted during O3 exposure, the observed increases in circulating cholesterol and phytosterols suggest decreased catabolism of cholesterol. Bile acid production is one important mechanism for eliminating cholesterol through excretion. The observed decreases in several bile acids and an intermediate of bile acid synthesis from cholesterol suggest that decreased bile acid production may contribute to elevated serum cholesterol. These data are supported by evidence that the transcription of essential genes involved in cholesterol and steroid synthesis was suppressed in the liver.

Notably, O3-induced increases in several circulating BCAA including muscle-specific protein catabolites, combined with the observed decrease in TCA cycle intermediates, may reflect increased protein catabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction. Given the fact that BCAA are known to regulate insulin production (Lu et al., 2013), their increases in the circulation after O3 exposure might influence insulin action in peripheral tissues. Stress has been shown to augment the catabolic state and therefore increases the utilization of BCAA for energy production in organs such as liver (Biolo et al., 1997; Porter et al., 2013). It has been shown that muscle protein catabolism is stimulated under stress to provide necessary precursor amino acids for the liver to synthesize large amounts of acute phase proteins (Biolo et al., 1997). In addition, the increases in the expression of gluconeogenic enzymes involving BCAA suggests their use in energy production by the liver.

Changes in liver gene expression were not restricted to metabolic processes, rather genes involved in apoptosis and mitochondrial function were remarkably impacted by O3. O3 exposure also changed the expression of several genes involved in inflammatory processes that tended to be inhibited rather than induced. Air pollution has been recently linked to non-alcoholic liver disease, also known as liver steatohepatitis (Zheng et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2014). One experimental study involving long-term exposure to concentrated ambient PM has shown liver inflammation, fibrosis and changes in markers of insulin signaling (Zheng et al., 2013). Marked acute effects of O3 on liver gene expression reflecting apoptosis, alteration of mitochondrial function and metabolic processes in the present study support the hypothesis that air pollutants could, over a long period of time, induce liver disease. The mechanisms by which O3 may lead to acute changes in liver gene expression and contribute to long-term disease will need to be examined further.

Although a number of studies have shown an increased release of inflammatory mediators from the lung into the circulation following exposure to air pollutants, specifically PM (Finnerty et al., 2007; Mutlu et al., 2007; Delfino et al., 2008), O3 did not significantly increase serum IL-6 levels in this study. We and others have previously shown that acute O3 alone did not influence other serum inflammatory biomarkers such as TNF-α (Urch et al., 2010; Bass et al., 2013). Additionally, metabolic impairment was noted at 0.5 ppm without changes in indicators of lung injury or inflammation, suggesting that the immediate metabolic response likely resulted from neurohumoral activation and not from cytokines released systematically.

Some of the metabolic effects of O3 observed immediately following day 1 were reduced upon the second day of exposure, and most were reversed upon an 18 h recovery period. This is critical in considering the relevance of these observations to humans who are exposed episodically over their lifetime. The reduction of O3 effects upon subsequent exposure might relate to the adaptation that has been widely reported in pulmonary injury and inflammation (Brink et al., 2008; Hamade and Tankersley, 2009); however, the mechanisms are poorly understood. We observed that the adaptation response to O3 might also involve reduced metabolic impairments upon subsequent exposure. It is likely that the degree of adaptation responses vary between animal species and strain (Hamade and Tankersley, 2009). In our prior study, we observed that episodic subchronic O3 exposure might reduce some of the acute metabolic effects in BN rats; however, glucose intolerance was still apparent after a 13 week episodic exposure (Bass et al., 2013). Thus, the metabolic consequences of low-level episodic O3 exposure are likely dependent upon the nature of that episodic exposure, the underlying genetic susceptibility and the biomarker of interest. Chronic stress has been linked to a rise in circulating lipids, insulin resistance and increased incidence of diabetes (Kelly and Ismail, 2015). Thus, it remains to be established if long-term O3 exposure might be linked to insulin resistance and diabetes predisposition through chronic stress and persistent metabolic alterations. The EPA.gov site states that the average O3 concentration that humans are exposed to across the United States is at or below the National Ambient Air Quality Standard of 0.075 ppm, with higher levels (0.2 to 0.3 ppm) seen frequently in regions with hot climates (Calderón-Garcidueñas et al., 2000). The 1.0 ppm O3 concentration used in this study for most analysis is considered high compared to human relevant doses. However, it has been shown that rats require three to four times the concentration of O3 to acquire an equivalent dose to humans (Hatch et al., 1994). Thus, the concentrations of O3 used in our study, although higher than ambient levels, are appropiate for rodent exposures.

In conclusion, we show that the inhaled pulmonary irritant O3 is able to induce systemic metabolic changes, as seen by hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance, leptinemia, increased serum FFA, cholesterol, and BCAA together with varied changes in liver transcriptome expression involving the processes of apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction and the alterations of glucose, protein and lipid metabolism. The known increases in epinephrine (Bass et al., 2013) and corticosterone (Thomson et al., 2013), together with the nature of systemic metabolic changes involving multiple central and peripheral tissues, provides supportive evidence for the involvement of a stress response in O3-induced systemic metabolic impairment. Further studies will be required to determine the likely long-term consequences of these metabolic alterations on insulin resistance. Although the immediate metabolic responses are not associated with the systemic increases in inflammatory cytokines, the contribution of chronic systemic inflammation might be important in the development of metabolic disorders.

Transparency document

The Transparency Document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Beth Owens, Barbara Buckley and Christopher Gordon of the US EPA for their critical review of the manuscript. We thank Mr. Dock Terrell of the U.S. EPA for conducting O3exposures. This research was supported by the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill’s Initiative for Maximizing Diversity (IMSD) grant (5R25GM055336), US-EPA-University of North Carolina-Co-Operative Trainee Agreement (#CR-83515201) and NIEHS Toxicology Training Grant (T32 ES007126). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- O3

Ozone

- WKY

Wistar Kyoto Rat

- FA

Filtered Air

- FFA

Free Fatty Acids

- BCAA

Branched Chain Amino Acids

- BN

Brown Norway Rat

- HDL-C

High Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- TNF-α

Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha

- HPA

Hypothalamus Pituitary Adrenal

- GTT

Glucose Tolerance Test

- I.P.

Intraperitoneal

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The research described in this article has been reviewed by the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Agency, nor does the mention of trade names of commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.025.

References

- Barnes VM, Kennedy AD, Panagakos F, Devizio W, Trivedi HM, et al. Global metabolomic analysis of human saliva and plasma from healthy and diabetic subjects, with and without periodontal disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass V, Gordon CJ, Jarema KA, Macphail RC, Cascio WE, et al. Ozone induces glucose intolerance and systemic metabolic effectsin young and aged brown Norway rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013;273:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biolo G, Toigo G, Ciocchi B, Situlin R, Iscra F, et al. Metabolic response to injury and sepsis: changes in protein metabolism. Nutrition. 1997;13:52S–57S. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SR, Edwards AV, Hardy RN. The role of the autonomic nervous system in the control of glucagon, insulin and pancreatic polypeptide release from the pancreas. J. Physiol. 1978;280:9–23. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink CB, Pretorius A, van Niekerk BP, Oliver DW, Venter DP. Studies on cellular resilience and adaptation following acute and repetitive exposure to ozone in cultured human epithelial (HeLa) cells. Redox Rep. 2008;13:87–100. doi: 10.1179/135100008X259187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Jerrett MP, Brook JRP, Bard RLMA, Finkelstein MM. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and traffic-related air pollution. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008;50:32–38. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31815dba70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs RM, Chun SJ, Niijima A, Romijn HJ, Nagai K. Parasympathetic and sympathetic control of the pancreas: a role for the suprachiasmatic nucleus and other hypothalamic centers that are involved in the regulation of food intake. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;431:405–423. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010319)431:4<405::aid-cne1079>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse JB, Freeman JL, Edelman SV, Jovanovic L, McGill JB. Serum 1,5-anhydroglucitol (GlycoMark): a short-term glycemic marker. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2003;5:355–363. doi: 10.1089/152091503765691839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas L, Mora-Tiscareño A, Chung CJ. Exposure to air pollution is associated with lung hyperinflation in healthy children and adolescents in Southwest Mexico City: a pilot study. Inhal. Toxicol. 2000;12:537–561. doi: 10.1080/089583700402905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. Inflammation, neurodegenerative diseases, and environmental exposures. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1035:117–132. doi: 10.1196/annals.1332.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey GB. Mechanisms regulating adipocyte lipolysis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998;441:157–170. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1928-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Schwartz J. Metabolic syndrome and inflammatory responses to long-term particulate air pollutants. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:612–617. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciencewicki J, Trivedi S, Kleeberger SR. Oxidants and the pathogenesis of lung diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;122:456–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hoon MJ, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaven CD, Evans AM, Dai H, Lawton KA. Organization of GC/MS and LC/MS metabolomics data into chemical libraries. J. Cheminform. 2010;2:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino RJ, Staimer N, Tjoa T, Polidori A, Arhami M, et al. Circulating biomarkers of inflammation, antioxidant activity, and platelet activation are associated with primary combustion aerosols in subjects with coronary artery disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:898–906. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour S, Lebon V, Shulman GI, Petersen KF. Regulation of net hepatic glyco-genolysis and gluconeogenesis by epinephrine in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;297:E231–E235. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00222.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AM, DeHaven CD, Barrett T, Mitchell M, Milgram E. Integrated, nontargeted ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry platform for the identification and relative quantification of the small-molecule complement of biological systems. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:6656–6667. doi: 10.1021/ac901536h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farraj AK, Hazari MS, Winsett DW, Kulukulualani A, Carll AP, et al. Overt and latent cardiac effects of ozone inhalation in rats: evidence for autonomic modulation and increased myocardial vulnerability. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120:348–354. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerty K, Choi JE, Lau A, Davis-Gorman G, Diven C, et al. Instillation of coarse ash particulate matter and lipopolysaccharide produces a systemic inflammatory response in mice. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2007;70:1957–1966. doi: 10.1080/15287390701549229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gackiere F, Saliba L, Baude A, Bosler O, Strube C. Ozone inhalation activates stress-responsive regions of the CNS. J. Neurochem. 2011;117:961–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CJ, Johnstone AF, Aydin C, Phillips PM, MacPhail RC, et al. Episodic ozone exposure in adult and senescent Brown Norway rats: acute and delayed effect on heart rate, core temperature and motor activity. Inhal. Toxicol. 2014;26:380–390. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2014.905659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]