Abstract

Background

Skin bleaching is a widespread phenomenon in spite of their potentially toxic health effects.

Objectives

This study aimed to determine if such products are used in Sweden in particular by pregnant women, furthermore to explore immigrant women's view skin bleaching.

Methods

455 pregnant women completed a questionnaire, which were statistically analysed. Focus groups and individual interviews were conducted with immigrant women, content analysis was used to assess the data.

Results

Skin bleaching products were used by 2.6% of pregnant women, significantlly more by women born in non-European countries. Motivating factors were associated with the concept of beauty together with social and economic advantages. The women had low awareness of the potential health risks of the products. Regulations on the trade of skin bleaching products have not effectively reduced the availability of the products in Sweden nor the popularity of skin bleaching.

Conclusion

There is need for further research especially among pregnant women and possible effects on newborns. Products should be tested for toxicity. Public health information should be developed and health care providers educated and aware of this practice, due to their potential negative health implications.

Keywords: Skin bleaching, harmful practice, pregnancy

Introduction

Skin bleaching refers to the use of chemical agents to lighten skin colour. Such products can be prescribed to treat hyperpigmentation disorders1, but are more frequently used intentionally to lighten skin complexion. The regular and sustained use of skin bleaching products has been practiced in African and Asian contexts for decades, with prevalence estimates from 25% to 96%2–6. Skin bleaching continues to affect communities “of colour” disproportionately6, but has extended beyond the African and Asian continents7–11. While traditionally a female practice, use has become more popular also among men in recent years12.

Skin bleaching products include creams, ointments, soaps, capsules/pills, and injections. The most commonly used products contain hydroquinone, corticosteroids or mercury4. These agents act in different ways to lighten skin, but generally work by suppressing the production of melanin, the pigment which gives human skin its colour13–15. While effective in lightening skin colour, the products are also associated with health risks, such as dermatitis, impaired wound healing and adrenal suppression12,16. Mercury is associated with adverse neurological, psychological and renal effects and organic mercury compounds also have the ability to cross the placenta with toxic effects for the foetus3,12,15,16–19.

Medical concerns about safety have resulted in more stringent regulations and prohibitions on the production and trade of certain products in many countries. These efforts, however, appear to have done little to curb the growing popularity of skin bleaching around the world, nor the widespread availability of the products6,20,21. Health problems are regularly observed, and globalisation continues to fuel the flow of goods7–8,22–23. To our knowledge, there are no formal studies assessing the prevalence of skin bleaching products in Sweden. Given the widespread use and popularity of skin bleaching products globally and their potential adverse health effects, it is critical to address this knowledge gap in Sweden today, where immigrants comprise 15% of the country's population24. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of skin bleaching among pregnant women in Sweden, and further to explore the perceptions of immigrant women on practice, safety, availability of skin bleaching products, and underlying factors motivating a preference for lighter skin.

Methods

An exploratory design was chosen to answer the research questions as there were no earlier studies in Sweden to build upon. In the tradition of methodological triangulation25, we selected a combination of quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques to gain a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon of skin bleaching. The qualitative methods were also used to follow-up on unanswered questions which emerged during the analysis of the quantitative data.

Quantitative component

At a university hospital in Sweden, the two senior reseachers, who planned the study, invited all pregnant women attending a routine ultrasound examination during weeks 16–18 gestation to answer a short anonymous questionnaire while awaiting their appointments (July to October 2012). The women were given the study information and questionnaires at the time of arrival to the hospital for their routine scans, by a receptionist. The midwives and doctors providing the ultrasound were not involved in the study, which was completed before the medical examination. The documents were available in Swedish, English, French and Kiswahili. The questionnaire contained five closed questions on socio-demographic information and obstetric history, one question on prior and present use of skin bleaching products and, for users, questions regarding duration, frequency, satisfaction and if adverse effects were observed. Three open questions explored what kind of products were used, where the products were applied and what kind of adverse effects were obeserved, if any. The questionnaires were voluntarily returned, placed in a sealed box in the waiting room of the clinic. The box was emptied every other day by one of the reserachers. The responses were entered into a statistical database created using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 18. Data was summarised in frequency tables. Chi-square tests were used for comparison between users and non-users. The results were considered significant at p-values of less than 0.05.

Qualitative component

The second stage of the study involved a further three months of data collection (November 2012 to January 2013). Three focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in a meeting room at the hospital, with four women in each group. African women participated in the first two groups and Asian women in the third FGD. The FGDs lasted approximately 60 minutes each. Four individual interviews were conducted face-to-face in one of the university offices or, over the internet, with Skype or Facebook Messenger. We identified participants using snowball sampling; immigrant women known to the study researchers were asked to help in identifying other participants from their social networks for the study. One of the researchers contacted the women and explained the purpose and procedures for voluntary participation. The FGDs and interviews were conducted in English, as all participants were fluent in English, using a topic guide covering perceptions on the use of skin bleaching products, motivations for skin bleaching, knowledge of the safety and types of products used, and their availability in Sweden.

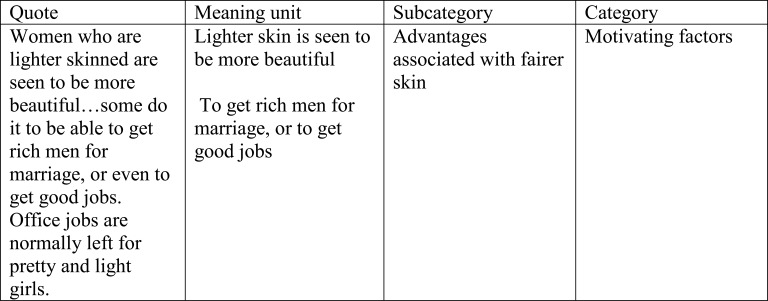

Extensive written notes were taken during the FGDs and interviews, by the last author, JO. Qualitative content analysis according to Graneheim & Lundman was followed26 and used. The textual data was read by all authors, who identified meaning units, coded and organised them into sub-categories and categories (Figure 1). The authors discussed the categories emerging from the data. After analysing two FGDs and all individual interviews, we decided to conduct a focus group with women born in Asian countries to check for potential variation in the phenomenon of skin bleaching by continents. However, similar findings were acquired.

Figure 1.

Example of the analytical process moving from interview text to meaning units, sub-categories, and categories.

Study group

The combined clinical, research and life experiences of the multidisciplinary group of researchers ensured capacity to perform this mixed methods study with competence. ED and BMA planned the study and JO, PhD-student born in Kenya, but resident in Sweden during the study period, carried out the qualitative discussions and interviews. BMA, also born in Kenya, has vast relevant experience on the interplay of ethnicity and women's health issues in various African countries. JI, BMA and ED brought expertise on the analysis of qualitative data to the team. ED, gynecologist/obstetrician, consultant at the university hospital during the study period, contributed with clinical knowledge and practice of both quantitative and qualitative research.

Ethical clearance

Permission for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board, Uppsala,Sweden (Dnr 2011/020). All women in the study were given verbal and written information on the principle of voluntary participation to ensure that they were not obliged to participate and could decide to stop without implications for their health care. When a pregnant woman decided to answer the anonymous questionnaire and leave it in the sealed box, we considered she had provided informed concept to participate in the study, a procedure accepted by the ethics review committee. The questionnaires were anonymous, thus findings could not be linked to any respondent.

Results

Quantitative

During the study period, 857 pregnant women attended the antenatal clinic for routine ultrasound examinations and 455 (53%) completed the study questionnaires (Table 1). Eighty-five percent (388) of the participants were born in Sweden, 14% (65) were born in other countries, and two women did not indicate their birth country. Sixty percent of the participants had completed a university education. The foreign-born participants were originally from 39 countries, 17 in Europe, 13 in the Middle East and Asia, eight in Africa and one in South America. There were no significant differences between users and non-users according to age or parity. Twelve of the 455 women (2.6%) stated they used skin bleaching products. Four women were Swedish, three were originally from Asian countries, two from African countries, two from the Middle East, and one woman did not list her country of origin, parity or highest education. Significantly more women (p=<0,001) born in other countries were current users (12%) of skin bleaching products, than the Swedish born women.

Table 1.

Distribution of pregnant women in Sweden on usage of skin bleaching products

| Non users n=443 | Users n=12 | |

| Mean age and range, years | 30 (16–49) | 29 (26–44) |

| First pregnancy | 195 (44%) | 5 (45%) |

| Second or more pregnancy | 249 (56%) | 6 (55 %) |

| Higher education | 266 (60%) | 7 (64%) |

| Born in Sweden | 384 (87%) | 4 (33%) |

| Born in other countries | 57 (13%) | 8 (67%) |

| Unknown birth country | 3 (0,7%) | 1 (8%) |

The women used these products for prolonged periods, all but one stating they had used the products for either 3 to 6 years or more than 6 years. The women primarily used cream products, and mainly applied the products to their faces. The majority of women (72.7%) using the products were satisfied with the results, and no one mentioned any side effects from the products.

Qualitative

Sixteen participants were foreign-born women, ranging in age from 22 to 50 years. They had all immigrated to Sweden from African and Asian countries including Kenya, Uganda, Burundi, Bangladesh, Thailand, Vietnam and India. The results of the FGDs and individual interviews support the findings from the questionnaire, that bleaching products are used in Sweden, and primarily by immigrant women. The interviews disentangled some of the complex reasons why women use these products; how the safety and efficacy of the products is perceived; and how easily skin bleaching products are obtained. Three categories were developed through the analysis process.

Motivating factors

Bleaching practices and womens' motivations for it, were discussed with ease, and described as constant and ubiquitous both in women's home countries and social circles in Sweden — a common daily activity, similar to “brushing one's teeth”. On the surface, the primary motivation for skin bleaching was explained simply as a means “to be much more beautiful”. There was no consensus amongst participants on an ideal image or definition of beauty, but it was accepted that beauty equated to fairer skin, with fairness being a relative concept. These discussions typically turned to the factors underlying the equation of fair skin and beauty. Participants commented on the role of Western and local media and marketing influences in transporting and perpetuating a Western image, and how producers attempt to appeal to local standards of beauty by using models from the region.

Look at all the celebrities and all the advertisements. All those people on those posters look almost white. If it were not for their other physical features, they would pass for white people. And who does not want to become as popular as them? (Thai woman).

A commonly shared explanation for the positive correlation between fair skin and beauty was that it extended to a range of tangible social and economic benefits, including access to better job opportunities, higher social status, better marriage proposals, and better life circumstances in general.

Women who are lighter skinned are seen to be more beautiful… some do it to be able to get rich men for marriage, or even to get good jobs. Office jobs are normally left for pretty and light girls. (African FGD).

Some women even apply these products to their children in Sweden. You find them using different creams on the children to make their complexions lighter…so they do not get dark. (Burundi woman)

The participants referred mostly to skin bleaching practices in their home countries. However, they consistently agreed that the same beliefs and motivations for skin bleaching applied to their lives in Sweden. Thus the practice of skin bleaching, and the beliefs underlying it, seem to follow with immigration.

Light-skinned women are treated better back home and yes even here in Sweden. (Kenyan woman).

Perceived health risks

The FGDs included awareness and concerns about potential health risks associated with the use of skin bleaching products. A number of superficial side effects to the skin were mentioned, especially discolouration, greyness, redness and patching. Other women disagreed that the products had any negative side effects, or did not consider them significant.

Some people have been using these creams for a long time and I rarely see any side effects. I have been using it on my face for six years now and my face is much smoother than it ever has been. I think the side effects are overrated. (Asian FGD).

Other health consequences were cited, such as wounds that would not heal, skin infections, allergies, ulcers and thinned skin. It is notable that much of this knowledge was based on speculation or hearsay.

There are many people who say that those who bleach, especially those who use tablets and injections, cannot be operated upon as their skin is so thin and does not heal properly. I do not know how true that is,… who knows, but the chemicals in these products cannot be without any side effects? (African FGD).

In regard to the safety of the products, participants had little knowledge about the contents or ingredients in skin bleaching products, nor any potential side effects including potential transmission through the placenta with effects to the foetus.

I don't think the products have side effects for pregnancies or children…if you are just applying it on your skin, then I think it's only the mother being affected. (African FGD).

The ingredient lists on product packages were not considered helpful as they primarily contain names without meaning for the average consumer. Where negative health consequences were mentioned in the discussions, they were attributed to use of cheaper or homemade bleaching products. Expensive products were perceived to be safe(r).

Some people use Jik, you know that product for keeping clothes white? They shower and scrub their bodies with Jik. There are many household products that people use, especially those that are acid-based. They really sting and burn the skin…Women who have lots of money use pills and injections to lighten their skin. That way, they get a more uniform skin change…some of the creams irritate the skin, so it's much better with the injections and pills. (African FGD).

Another belief was that the effects of bleaching are reversed upon discontinuation of use. This discussion touched on the psychological complexity inherent in the use of skin bleaching products.

It is very difficult to stop bleaching. You see, when you stop using them, you reverse the benefits. Even though many people lighten their skin, they do not want people to know they are engaged in the practice. Many people like lighter-skinned women, but they look down upon skin bleaching practice. So many people that do bleach will rarely stop. (African FGD).

Availability of skin bleaching products in Sweden

Participants were unanimous that an extensive range of products are readily available for purchase in various shops in Sweden and on the internet.

Skin lightening in Sweden is very common…There are many people who bleach their skin here… You can get a range of products here in Sweden, some I had never even seen before I came here. (Thai woman).

The women in our study also explained that skin bleaching supplies were frequently brought back to Sweden following visits to their home countries, or were sent by post from friends and family.

Discussion

In this study we find that potentially toxic skin bleaching products are easily obtained and used in Sweden and long-term use is the norm also during pregnancy. Mahé et al, reports from Senegal that the cosmetic use of hydroquinone and corticosteroids were extensively prevalent among pregnant women and with negative impact on birth and placenta weights3. Skin bleaching is motivated by complex psychological, economic and social factors. In agreement with other studies, we found that having a lighter shade of skin colour is always preferable, irrespective of one's original colour21. According to Franklin in, ‘Living in a Barbie world,’ “there exists a social premium on light skin across races and this is a manifestation of white privilege. Regardless of one's race, being closer to looking white accrues privileges tied to being white”21. The disproportionately high social capital attributed to fair skin is so powerful that women in our study spoke about mothers who also bleached their children's skin.

A global overview of the geographic distribution of wealth based on household income shows the biggest gaps in equality fall cleanly along racial lines27. Margaret Hunter writes that, “Many female bleachers observe the acute correlation between race and socio-economic class and want to improve their opportunities in the local employment and marriage markets, as well as adopt a cosmopolitan, modern identity”28. The respondents in our study adhered to the same perception, that fairer skin is endowed with both social privilege and financial advantage and thus bleaching is motivated by aesthetic ideal, but also on a calculated analysis.

Hunter writes that there is shame around skin lightening in some cultures “either because one should ‘naturally’ have light skin, not chemically derived light skin, or because some believe that lightening the skin implies a shame of one's race or ethnic identity”28. We did not focus on the psychological impact of skin bleaching in our study, and further research on shame or stigma associated with the practice is necessary.

Public health information and necessary consumer information on the potential health risks of skin bleaching is limited and we found that women use skin bleaching products without adequate information about their potential health risks. Neither health care practitioners nor governments have prioritised this as important patient and public health information. Furthermore our results indicate that national and international regulations, including prohibitions, on the manufacture and distribution of skin bleaching products, have not affected the availability of the products.

Strengths and limitations

A detailed description of the study design and participants has been provided for the readers to ensure trustworthiness and transferability of the findings. JO and BMA, both African women, have personal experience as immigrants in Sweden, which may have facilitated participants in relating to the topic and engaging in the interviews.

We chose to keep the questionnaire short, to reduce the burden for potential participants awaiting their ultrasound. With 53% responded, we have no information from those who decided not to answer, and thus true prevalance could be different from what was found. Irrespective, skin bleaching is present in Swedish society, and among pregnant women, with potential health effects. The target group of pregnant women in the quantitative part of the study can be discussed. Sweden is a multiethnic country and we wanted to mirror the population and not only explore the practice of skin bleaching among women of colour. We were interested to determine if prevalence was high enough to continue with testing for toxic products in the umbilical cord, blood, hair and urine of newborns, which we had ethical clearance to do. However, prevalence was low, and we concluded that the sample size for such an investigation could not be reached at present time in Sweden. A limitation was that we asked participants for their country of origin, rather than their ethnicity or skin colour, which would have been optimal and should be refined in future studies. Information on specific brands of skin bleaching products were not included in the questionnaire, thus we do not know the exact products and cannot assess their relative harmfulness or toxicity. Our study population reflected national statistics for pregnant women in Sweden regarding age, parity and immigration background, except for a slightly higher proportion with university education, which is not surprising as the study was performed in a university region.

This study illustrates a practice used among pregnant women and immigrant women. It shows the need to bring such knowledge forward in public and antenatal health services, particularly regarding the potential negative effects, as has been done with warnings regarding smoking and drinking alcohol. We do not know the extent of skin bleaching practice among non-pregnant women, and studies are needed to investigate this population as well. However cultural practices continue to spread globally and adverse medical effects will be strenuous on already limited health care resources. We encourage continued research into the multiple dimensions and implications of skin bleaching such as motivating factors for the use of these products, toxicity, sale, purchase and trade and identify effective alternative skin bleaching agents. Information on the potential adverse health effects is needed29, and studies of the health implications for infants, has to be carried out in a country where cosmetic skin bleaching is more commonly used than in Sweden3. As bleaching products are sold and used in Sweden, this knowledge is important to advocate for changes to the deeply-rooted and more insidious factors, such as racism, and to challenge widespread associations between fairer complexions, social status and beauty.

References

- 1.Dadzie OE. A review of misuse of cutaneous depigmenting agents. Eur Dermatol. 2010;5:74–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03150.x. PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wone I, Tal-Dia A, Diallo OF, Badiane M, Toure K, Diallo I. Prevalence of the use of skin bleaching cosmetics in two areas in Dakar (Senegal) Dakar Med. 2000;45(2):154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahé A, Perret JL, Ly F, Fall F, Rault JP, Dumont A. The cosmetic use of skin-lightening products during pregnancy in Dakar, Senegal: a common and potentially hazardous practice. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(2):183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladizinski B, Mistry N, Kundu RV. Widespread use of toxic skin lightening compounds: medical and psychosocial aspects. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29(1):111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ly F, Soko AS, Dione DA, Niang SO, Kane A, Bocoum TI, et al. Aesthetic problems associated with the cosmetic use of bleaching products. Int J Dermatol. 2007 Oct;46(Suppl 1):15–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blay YA. Skin bleaching and global white supremacy: by way of introduction. J Pan African Studies. 2011;4(4):4–46. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petit A, Cohen-Ludmann C, Clevenbergh P, Bergmann JF, Dubertret L. Skin lightening and its complications among African people living in Paris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5):873–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mistry N, Shapero J, Kundu RV, Shapero H. Toxic effects of skin-lightening products in Canadian immigrants. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15(5):254–258. doi: 10.2310/7750.2011.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. Mercury exposure among household users and nonusers of skin-lightening creams produced in Mexico - California and Virginia, 2010 Internet. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA); 2012. Jan 20, cited 2014 December 1. Report No.: 61. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6102a3.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Son KH, Heo MY. The evaluation of depigmenting efficacy in the skin for the development of new whitening agents in Korea. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2013;35(1):9–18. doi: 10.1111/ics.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.al-Saleh I, al-Doush I. Mercury content in skin-lightening creams and potential hazards to the health of Saudi Women. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1997;51(2):123–130. doi: 10.1080/00984109708984016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dadzie OE, Petit A. Skin bleaching: highlighting the misuse of cutaneous depigmenting agents. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(7):741–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimbow K, Obata H, Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB. Mechanism of depigmentation by hydroquinone. J Investig Dermatol. 1974;62(4):436–449. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12701679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denton CR, Lerner AB, Fitzpatrick TB. Inhibition of melanin formation by chemical agents. J Investig Dermatol. 1952;18(2):119–135. doi: 10.1038/jid.1952.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olumide YM, Akinkugbe AO, Altraide D, Mohammed T, Ahamefule N, Ayanlowo S, et al. Complications of chronic use of skin lightening cosmetics. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(4):344–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engler DE. Mercury “bleaching” creams. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(6):1113–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de la Cuadra J. Cutaneous sensitivity to mercury and its compounds. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1993;120(1):37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira DB, Foster G, Savill J, Syme PD, Taylor A. Membranous nephropathy caused by mercury-containing skin lightening cream. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1987;63(738):303–304. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.63.738.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harada M. Congenital Minamata disease: Intrauterine methylmercury poisoning. Teratology. 1978;18(2):285–288. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420180216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anekwe ON. The global phenomenon of skin bleaching: a crisis in public health (Part 1). Voices in Bioethics: An Online Journal Internet. 2014. Jan 29, cited 2014 Nov 14. Available from: http://voicesinbioethics.org/2014/01/29/the-global-phenomenon-of-skin-bleaching-a-crisis-in-public-health-an-opinion-editorial-part-1/

- 21.Franklin I. Living in a Barbie world: skin bleaching and the preference for fair skin in India, Nigeria, and Thailand Senior Honors Thesis. Stanford, CA: Stanford University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKelvey W, Jeffery N, Clark N, Kass D, Parsons PJ. Population-based inorganic mercury biomonitoring and the identification of skin care products as a source of exposure in New York City. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(2):203–209. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith RD. Trade and public health: facing the challenges of globalisation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(8):650–651. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistics Sweden (PopulationUnit), author Utrikes födda Internet. 2012–2013. cited 2014 Dec 4. Available from: http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Artiklar/Fortsatt-okning-av-utrikes-fodda-i-Sverige/

- 25.Denzin NK. Sociological methods: a sourcebook. New Jersey: Aldine Transaction Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies JB, Shorrocks A, Sandstrom S, Wolff EN. The world distribution of household wealth Internet. 2007 cited 22 Nov 2014. Center for Global, International and Regional Studies, University of California Santa Cruz; Available from: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/3jv048hx. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter ML. Buying racial capital: Skin-bleaching and cosmetic surgery in a globalized world. J Pan African Studies. 2011;4(4):142–164. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ajose FOA. Consequences of skin bleaching in Nigerian men and women. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:41–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02812.x. PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]