Abstract

While conflict-induced forced migration is a global phenomenon, the situation in Colombia, South America, is distinctive. Colombia has ranked either first or second in the number of internally displaced persons for 10 years, a consequence of decades of armed conflict compounded by high prevalence of drug trafficking. The displacement trajectory for displaced persons in Colombia proceeds through a sequence of stages: (1) pre-expulsion threats and vulnerability, (2) expulsion, (3) migration, (4) initial adaptation to relocation, (5) protracted resettlement (the end point for most forced migrants), and, rarely, (6) return to the community of origin. Trauma signature analysis, an evidence-based method that elucidates the physical and psychological consequences associated with exposures to harm and loss during disasters and complex emergencies, was used to identify the psychological risk factors and potentially traumatic events experienced by conflict-displaced persons in Colombia, stratified across the phases of displacement. Trauma and loss are experienced differentially throughout the pathway of displacement.

Keywords: Internal displacement, Internally displaced persons, Victims of armed conflict, Humanitarian crisis, Complex emergency, Forced displacement, Forced migration, Trauma signature analysis, TSIG

Introduction

In the annals of forced migration, Colombia is notable for the high overall numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs), the unrelenting and unidirectional flow of IDPs arriving in urban centers, and the protracted course of displacement [1••, 2••]. Colombia's unique trajectory of conflict-induced forced migration exposes IDPs to vacillating psychosocial ramifications throughout the phases of the displacement experience.

The Context of Forced Migration Worldwide

Forced migration, involving displacement of individuals, families, and entire communities from their homes and lands, is one of the most psychologically devastating consequences of persecution, armed conflict, generalized violence, and other types of human rights violations [3, 4••, 5, 6]. Forced migrants are repeatedly exposed to potentially traumatic events (PTEs) [5] and experience crippling losses that begin even before they are dispossessed of their homes, possessions, livelihoods, communities, and systems of social support [3, 4••, 5, 6].

The two major categories of persons who are forcibly displaced are IDPs [7••, 8, 9] and refugees [10]. The United Nations provides the following definition for IDPs:

“Internally displaced persons are persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized State border” [11••].

Refugees, in contrast, seek safety from armed conflict by escaping or fleeing from their home country and crossing an international frontier to reside in exile in another nation. Internationally, there are more than twice as many IDPs as refugees; a total of 15.4 million refugees were under UN surveillance in 2012 [8, 10], and the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) estimated the global tally of IDPs at 33.3 million persons for 2013 [7••]. By remaining within their home countries, IDPs may not be protected by the full spectrum of human rights safeguards that are accorded to refugees. Perhaps counterintuitively, results of several systematic reviews indicated that IDPS who remain within their own country experience worse mental health outcomes than refugees [3, 4••].

Colombian Forced Migration

Colombia is most notable for its accumulating census of IDPs, estimated at 5.7 million in 2013 [1••, 7••]. Moreover, these tallies of IDPs do not include the children who have been born into displacement. This creates a significant undercount of vulnerable youth directly affected by forced migration [7••, 8]. The Colombian armed conflict has also produced almost 400,000 refugees [9], but IDPs outnumber refugees 14 to 1.

Phases of Displacement

Colombian forced migration is a protracted process involving a sequence of life experiences that both precede and follow the focal episode when persons are forced to vacate their homes and abandon their communities, thus becoming IDPs. The acute trauma and life-changing losses that mark “the departure” (“la salida”) create a memorable punctuation point in the lifespan of forced migrants. IDPs experience extraordinary adversities, overt danger, and psychological distress throughout all phases along the trajectory of displacement, leading to chronic elevation of risks for victimization, physical ailments, and mental disorders.

Analyses and discussions presented here are stratified according to the “phases” of displacement. The following sequence of six phases collectively describes the “pathway” that Colombian IDPs must navigate physically and psychologically: (1) pre-expulsion threats and vulnerability in the community of origin, (2) precipitating event(s) leading to and including the moment of departure and displacement, (3) migration in search of a safer habitat, (4) transition and adaptation during initial relocation, (5) long-term resettlement (the end point for most Colombian IDPs), and (6) return to the community of origin (rare – but a primary focus of recent laws and programs). The unfortunate reality in Colombia is that most IDPs reach the stage of prolonged resettlement and have no practical possibility of returning to their communities of origin throughout the remainder of their lifetimes.

Psychological Consequences of Internal Displacement

Abrupt and coerced displacement is one of the harshest multiple-loss experiences imaginable [12, 13]. At the moment of departure, IDPs lose their homes, lands, animals, businesses, properties, assets, and personal possessions. They also lose their identities as productive landholders or gainfully employed citizens, their social status, their support networks, and their communities [1••, 2••, 7••, 8–10, 14]. The intensity of loss is often compounded by trauma. IDPs have been expelled from their homes, often by acts of extreme brutality [1••, 2••, 14]. In Colombia this has involved a range of threatened or actual atrocities including violent assaults, assassinations, massacres, publicly witnessed acts of violence against civic leaders, torture, kidnapping, forced disappearance, sexual assault, and forced recruitment of youth to serve in the ranks of guerrilla or paramilitary groups [1••, 2••, 12–17].

The circumstances of forced migration combine the stressors of extreme trauma with devastating loss in a manner that synergistically elevates the likelihood for progression to psychopathology. This includes increased risks for such common mental disorders (CMDs) as major depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorder, as well as somatic complaints and increased consumption of alcohol and illicit drugs [16–21].

Methods

Trauma Signature (TSIG) Analysis

To examine the psychological consequences of internal displacement in Colombia, we applied the established, evidence-based methodology of TSIG analysis [22•, 23]. TSIG analyses have been conducted on a range of disasters and extreme events. TSIG is premised on the assumption that each disaster or complex emergency exposes the affected population to a unique pattern of traumatizing hazards, losses, and changes. In the present study, TSIG analysis was used to examine the extent to which Colombian IDPs are exposed to empirically documented risk factors for psychological distress and mental health disorders [24–29] throughout the phases of displacement. Consistent with the Disaster Ecology Model [29–32], TSIG analysis advances the position that this singular “signature” of exposure risks is a predictor of the psychosocial and mental health consequences sustained by Colombian IDPs. Internal displacement in Colombia provides the context for extending TSIG applications from catastrophic natural disasters [33–38], human-generated (anthropogenic) technological disasters [39], and “hybrid” disasters (featuring both prominent natural and anthropogenic elements) [40, 41], to the realm of intentional, perpetrated acts of violence [42] and armed conflict situations that can evolve into complex emergencies [1••, 43–45].

Coordination of Subject Matter Expertise

This study was originally conceived by the originators of TSIG analysis (J.M.S., Y.N., Z.E.) and was further evolved by an expanded group of global mental health colleagues who joined them in Colombia to develop evidence-based outreach, screening, and intervention programs for Colombian IDPs (R.A., H.V., A.E.O.). During this period, the original TSIG analysis was performed, presented in international forums, and critiqued. Subject matter expert (SME) input was received from two of Colombia's leading psychiatrists (R.C., S.L.G.) and two renowned Latin American psychiatrists (M.A.O., M.L.W.). Based on the feedback received, the TSIG analysis was modified to examine hazards and stressors by phase of displacement. Psychologist colleagues who have participated in multiple previous TSIG analyses (D.R.G., F.E.W., M.E.), assisted by the team's research librarian (Y.G.-B.), joined forces to review the international psychological literature on forced migration. Two Colombian research assistants reviewed publications in Spanish (A.M.G.C., N.M.G.).

Analysis Sequence

The TSIG analysis reported here consisted of the following steps: (1) retrieval and synthesis of published reports in English and Spanish on internal displacement and forced migration globally and in Colombia (including the peer-reviewed scientific literature, government reports, published studies conducted by non-governmental organizations, and relevant laws and policies); (2) elucidation of the defining features of Colombian forced migration; (3) construction of a hazard profile by phase of displacement; (4) identification and documentation of prominent stressors faced by IDPs categorized into hazards, losses, and changes and stratified into the six phases of displacement; and (5) creation of a trauma signature summary based on the estimated psychological severity of exposures to salient hazards, losses, and changes.

Unique and Defining Features of Internal Displacement (Tables 1 and 2)

Table 1.

Top five nations in numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs), 2004-2013

| Rank | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Sudan | Colombia | DR Congo | Uganda | Iraq |

| 2005 | Sudan | Colombia | Uganda | DR Congo | Iraq |

| 2006 | Sudan | Colombia | Iraq | Uganda | DR Congo |

| 2007 | Sudan | Colombia | Iraq | DR Congo | Uganda |

| 2008 | Sudan | Colombia | Iraq | DR Congo | Somalia |

| 2009 | Sudan | Colombia | Iraq | DR Congo | Somalia |

| 2010 | Colombia | Sudan | Iraq | DR Congo | Somalia |

| 2011 | Colombia | Iraq | Sudan | DR Congo | Somalia |

| 2012 | Colombia | Syria | DR Congo | Sudan | Somalia |

| 2013 | Syria | Colombia | Nigeria | DR Congo | Sudan |

Table 2.

Distinguishing features of internal displacement in Colombia, South America

| Numbers and Time Trends | |

| 1 | Colombia has the largest population of conflict-affected internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the world. |

| 5.7 million in 2013 | |

| 2 | Children born to relocated/resettled IDP families are not counted in the total. |

| 3 | Colombia accounts for 17 % of IDPs in the world. |

| 5.7 million Colombian IDPs/33.3 million IDPs worldwide in 2013 | |

| 4 | Colombia accounts for 91 % of IDPs in the Western Hemisphere – geographically isolated from other major concentrations of IDPs worldwide. |

| 5.7 million Colombian IDPs/6.27 million IDPs in the Western Hemisphere in 2013 | |

| 5 | Colombian IDPs outnumber Colombian refugees 14 to 1. |

| 5.7 million Colombian IDPs and 394,000 Colombian refugees: 14:1 ratio | |

| 6 | Internal displacement in Colombia is unidirectional. |

| Almost no Colombian IDPs have been able to return to their homes. | |

| 7 | Colombian internal displacement has continued for decades. |

| 8 | Numbers of Colombian IDPs increase each year. |

| Context of Colombian Displacement | |

| 9 | Displacement takes place in the context of decades of armed insurgency. |

| 10 | IDPs are designated as a protected class of “victims of armed conflict”. |

| 11 | Colombian IDPs include a mixture of non-combatant civilians, current/former guerrilla, and current/former paramilitary members. |

| 12 | There is a complex relationship between drug trafficking and displacement. |

| Colombia is the major world source nation for cocaine. | |

| Colombia is one of two major suppliers of heroin entering the US. Seized lands have been used for drug crop cultivation, drug processing, transit, concealment of illicit activities, and expansion of the power base for armed actors. | |

| 13 | The predominant pattern of internal displacement is rural to urban. |

| Rural lands are seized. Relative safety is found in urban settings. | |

| Characteristics of Colombian IDPs | |

| 14 | Seventy percent (70 %) of Colombian IDPs are women and children. |

| 15 | Special populations are disproportionately represented. |

| Indigenous, Afro-Colombian, low educational attainment, low literacy subgroups | |

| 16 | Ninety-five percent (95 %) of Colombian IDPs work in the “informal sector”. |

| 17 | Resettled IDPs are difficult to locate and identify for services. |

| “Invisibility”: No IDP camps or geographically defined neighborhoods | |

| 18 | In Colombia, IDPs have no defining identity or unifying organization. |

| 19 | Colombian IDPs have no safe place to migrate and no safe alternatives to return to communities of origin. Many no longer wish to return. |

| 20 | Laws and programs to provide public health, psychosocial, and legal services – and land restitution – for IDPs are in the early stages. |

Distinguishing features of conflict-induced displacement in Colombia, relative to patterns of displacement worldwide, were identified through a combination of ongoing literature review and conversations with SMEs in Colombia and worldwide. Members of the author team have previously described some of the defining characteristics of Colombian forced migration [1••]. Findings reported here synthesize new information and expand previous discussion on this topic [1••].

Hazard Profile (Table 3)

Table 3.

Hazard profile of internal displacement Colombia, South America

| Disaster type | Definition | Armed conflict-induced forced migration resulting in large populations of internally displaced persons (IDPs) within Colombia and Colombian refugees in other nations: 2012-2013: 5.5-5.7 million IDPs in Colombia 2012-2013: 394,000 refugees outside Colombia |

| Disaster classification | Intentional anthropogenic (human-generated) armed conflict disaster involving massive population displacement and forced migration that has escalated into a protracted complex emergency and humanitarian crisis | |

| Hazard exposure by phase of displacement | Pre-expulsion: Hazards in community of origin |

Targeted threats of harm from armed actors Left-wing guerrillas Right-wing paramilitary Criminal bands (BACRIM) Narco-traffickers Colombian military forces Taxation of land-holding peasants (“campesinos”) Extortion Fraudulent actions to gain control of land Community exposures to violence in the area: Combat, homicides, kidnapping, forced disappearance, massacres, assaults, gender-based violence, improvised explosive devices, antipersonnel mines, terrorist acts, forced recruitment of local youth into guerrilla or paramilitary units Exposure to expulsion/displacement of neighbors or family members living in the area |

| Expulsion: Hazards that precipitate or “trigger” displacement |

Loss of land due to legal means Loss of land due to fraudulent sales Targeted, believable threats of harm from armed actors Left-wing guerrillas Right-wing paramilitary Criminal bands (BACRIM) Narco-traffickers Colombian military forces Direct infliction of harm: Assault, homicide, kidnapping, forced disappearance, massacres, gender-based violence, forced recruitment Atrocities committed against family, friends, or civic leaders |

|

| Migration: Hazards encountered while in transit to a safer locale |

Dangers experienced while moving to another site Transportation hazards Vulnerability to physical harm, assault, robbery Lack of access to survival necessities, sanitation Exposure to the elements |

|

| Transition and adaptation during initial relocation: Hazards encountered during early adjustment to displacement |

Lack of income to purchase survival necessities Dangers experienced in unfamiliar urban setting Exposure to urban environmental hazards, pollution Potential encounters with gangs, criminal bands Vulnerability to physical harm, robbery Potential surveillance of IDPs' movements by informants for the guerrilla or paramilitary |

|

| Long-term resettlement: Hazards encountered during protracted displacement in the community of resettlement |

Ongoing exposure to dangers in urban settings Limited income from employment in “informal sector” Job-related risks for physical injury Financial incentives to engage in illegal activities Exposure to pervasive urban violence including gang and criminal activities Interpersonal violence Partner/family violence Gender-based violence School bullying Drug trafficking-associated violence Availability/risks for substance use (alcohol, drugs) Urban areas under control by guerrilla, paramilitary, criminal bands, urban gangs |

|

| Return: Hazards encountered while attempting to return to community of origin, reclaim lands or property, and readjust |

Currently, there is extreme risk for those attempting to return to the communities of origin or to reclaim the properties that have been confiscated | |

| Place dimension | Community of “expulsion” Communities of origin from which IDPs are displaced |

Primarily rural Rural areas across Colombia Includes rural agrarian areas Includes mountain, jungle, other remote habitats Includes lands belonging to indigenous groups Focal areas of displacement change over time |

| Community of “resettlement” | Primarily urban Urban centers across Colombia Bogotá is the major “receptor” city |

|

| Time dimension | Duration of internal displacement in Colombia Duration of societal disruption |

Ongoing since the 1960s – more than 50 years Ongoing across all phases of displacement and forced migration |

| Duration of life/health risk | Continuous health risks across all phases of displacement and forced migration Risks for public health Risks for physical health Risks for mental health Displacement disrupts social support networks Displacement disrupts access to health care services For almost all IDPs, displacement is “protracted” For many IDPs, displacement is likely to be lifelong |

TSIG hazard profiles use an epidemiologic approach to disaster description that incorporates hazard, person, place, and time dimensions. Type of disaster was based on classification schemes used by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) [46] and the World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine [47].

This TSIG analysis examined the literature and fielded discussions among the co-authors and a wider network of SMEs to define the types of hazards and exposures encountered by IDPs. Displacement and adaptation progress through a series of “phases.” Although the circumstances of displacement are highly variable, for the purpose of this TSIG analysis, the “trajectory of displacement” is stratified into six relatively sequential “phases:” (1) pre-expulsion, (2) departure/expulsion, (3) migration, (4) transition and adaptation during initial relocation, (5) prolonged resettlement, and (6) (very seldom) return.

Psychological Stressor Matrix (Table 4)

Table 4.

Matrix of potentially traumatizing exposures and stressors for internally displaced persons in Colombia, South America by phase of displacement

| Phase of displacement | Types of exposures and stressors |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard | Loss | Change | |

| Pre-expulsion: Exposures and stressors in community of origin prior to expulsion |

Expulsion/displacement of neighbors or family members Actions of armed actors: Threats of harm Harm to person Harm to family member Forced recruitment of local youth Community exposures to violence in the area: Combat Assassinations Homicides Kidnapping Massacres Forced disappearances Exposure to interpersonal violence: Assaults, muggings Violence against women Child abuse Sexual violence Gang violence Violence: criminal bands Narco-trafficking Improvised explosive devices Antipersonnel mines |

Actions of armed actors: Legal processes to take possession of land Illegal processes to take possession of land Forced taxation of landholders Extortion, bribes Malfeasance Misfeasance |

Frequent change in control of region among armed actors |

| Expulsion: Exposures and stressors that precipitate or “trigger” displacement |

Actions of armed actors creating potentially traumatic events (PTEs): Targeted, believable threats of harm Direct infliction of harm to trigger displacement: Assassinations Homicides Kidnapping Massacres Forced disappearances Assaults, muggings Gender-based violence Atrocities committed against family, friends, or civic leaders Mass expulsion |

Loss of land due to legal means Loss of land due to fraudulent sales Acute losses: Land, crops, livestock Home and shelter Possessions Separation from family Loss of friends, neighbors Severe economic losses Loss of livelihood Loss of means of support |

Acute changes: Forced migration Displacement Homelessness Exposure to the elements Lack of basic necessities Lack of sanitation Lack of security Lack of privacy Disruption of essential services and health care Disruption of livelihood Disruption of “community” Loss of cultural heritage Immediate change in identity Dispossessed Unemployed Nomadic Dependent |

| Migration: Exposures and stressors experienced while in transit to a safer locale |

Exposure to dangers during transit to new locale: Risk of transport injuries Vulnerability to physical harm, assault, robbery Actions of armed actors: Surveillance of IDPs by armed actors during migration Threats against IDPs |

Lack of access to survival necessities, sanitation Lack of food, water Lack of toilets, sanitation Lack of clean, dry clothing Lack of clothing suitable to climate in area of relocation Lack of hygiene supplies Lack of home, shelter Limited cash to pay for necessities Lack of privacy, personal space Strong psychological reactions: Traumatic bereavement Complicated grief |

Engaging in survival behaviors while migrating Search for basic necessities Exposure of IDPs to: Harsh environment Lack of shelter Dependence on public transportation Uncertainty regarding destination Traveling through unfamiliar, disorienting, dangerous territory |

| Transition and adaptation during initial relocation: Hazards encountered during early adjustment to displacement |

Dangers experienced in unfamiliar urban setting Exposure to urban environmental hazards Exposure to violence Potential encounters with gangs, criminal bands Vulnerability to physical harm, robbery Exposure to the elements, pollution Potential surveillance of IDPs' movements by informants for the guerrilla or paramilitary Exposure to dangers in urban settings Exposure to pervasive urban violence including gang and criminal activities Urban areas of guerrilla, paramilitary, criminal control Dangers of physical injury related to types of available employment in “informal sector” Addictive behaviors Child abuse, sexual abuse, violence against women |

Lack of access to survival necessities Lack of adequate, safe shelter or housing Lack of food, clean water Lack of access to health care Lack of mental health care Lack of social network Lack of family supports Lack of friends, neighbors Lack of civic support resources Loss of landholder and breadwinner role/identity Loss of self-esteem Loss of independence Lack of access to survival necessities Poor quality, unsafe housing Lack of food, clean water Lack of access to health care Limited social network Limited family supports Limited friends, neighbors Limited civic support resources |

Initial adjustment to urban environment Lack of knowledge of resources Living in poverty with limited resources Economic uncertainty Lack of urban job skills Seeking employment in “informal sector” Criminal alternatives to earn money Access to alcohol, drugs Early adjustment to urban environment Living in poverty Economic uncertainty Employment in “informal sector” Criminal alternatives to earn money Vulnerability to scams, illegal operations Access to alcohol, drugs |

| Long-term resettlement: Exposures and stressors experienced during protracted displacement in the community of resettlement |

Ongoing exposure to dangers in urban settings Exposure to pervasive urban violence including gang and criminal activities Informal sector employment: high risks of injury, interpersonal violence, possible illegal activities Increased risk of partner/family violence Increased risks for use of alcohol drugs Risks to family members/children: e.g., school bullying Currently, there is extreme risk for those attempting to return to their communities of origin or to reclaim their properties |

Increasing access to survival necessities Improved quality of housing Access to basic necessities Expanding social network Family supports Increasing numbers of friends Access to some civic support resources |

Ongoing adjustment to urban environment Living in poverty Economic uncertainty Employment in “informal sector” Criminal alternatives to earn money Vulnerability to scams, illegal operations Access to alcohol, drugs |

| Return: Exposures and stressors experienced while attempting to return to community of origin, reclaim lands or property, and readjust |

Actions by armed actors In communities of origin Threats against IDPs attempting to return Assassinations of persons attempting to return and those who advocate for them |

Loss of social networks established in urban settings Loss of access to services available in urban settings |

IDPs opting not to return Do not want to re-adapt to rural living Prefer urban settings following adaptation Do not want to relocate children who have grown up in urban centers Belief that “return” will be a “second displacement” experience |

The next step involved matching the description of hazard exposures to the literature on psychological risk factors (for distress, disorder, and psychiatric diagnosis). This was summarized in a “stressor matrix.” In parallel with the hazard profile, risk factors and stressors are presented for each of the six stages of displacement, subcategorized into exposures to hazards, losses, and changes.

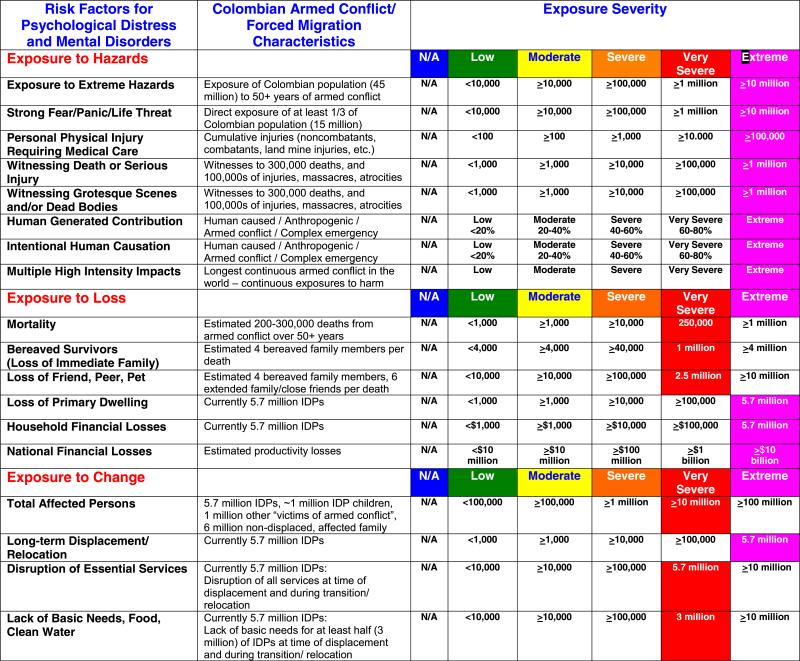

Trauma Signature Summary (Table 5)

Table 5.

Armed conflict and forced migration in Colombia, South America: Trauma signature summary

As a final step in the TSIG analysis, a composite trauma signature summary table was constructed, displaying some of the most significant evidence-based psychological risk factors, grouped under the headings of hazards, losses, and changes. The table presents exposure severity ratings for the risk factors. The ratings use ten-fold (order of magnitude) differences between adjacent categories. Based on CRED's database of international disaster events, dating from 1900 to the present [46], ratings of “extreme” for a specific risk factor are reserved for disasters that produce consequences at that order of magnitude only several times every 50 to 100 years. “Very severe” ratings reflect the order of magnitude threshold reached with a frequency of one or several times within a 10-to-20 year period, while “severe” ratings occur one or several times within a 3–5-year period.

Results

Unique and Defining Features (Tables 1 and 2)

Colombia is the only nation to have been consistently ranked either first or second in numbers of IDPs each year over the 10-year period 2004-2013 (Table 1). In 2013, Colombia's 5.7 million IDPs represented 17 % of IDPs worldwide and 91 % of IDPs throughout the entire Western Hemisphere. Based on the landmark Law 1448 (Law of the Victims and Land Restitution) passed in 2011, Colombian IDPs are now designated as a protected class of citizen “victims of armed conflict” [48••]. Colombia has instituted an ambitious strategy for providing health, social, and legal services for IDPs while simultaneously promulgating policies designed to allow some IDPs to return and reclaim their lands.

Hazard Profile (Table 3)

Forced migration in Colombia is classified as an intentional anthropogenic (human-generated) armed conflict disaster involving massive population displacement and forced migration that has escalated into a protracted complex emergency and humanitarian crisis. Most evident in the review of hazards are the findings that Colombian displacement has continued for decades and the hazards change over time and across phases. Although the types of hazards vary, the common element throughout the forced migration trajectory is unrelenting exposure to perceived threat and overt harm in a manner that jeopardizes life and livelihood.

Matrix of Potentially Traumatizing Exposures and Stressors (Table 4)

Stressors and PTEs proliferate throughout every phase of displacement. However, what is apparent is that the proportionate balance of exposure to trauma and loss changes according to phase of displacement. During the pre-expulsion phase, harm is threatened and future loss looms. The expulsion phase is typically brief but marked by fear of imminent harm or actual perpetrated harm, compounded by the finality of massive loss at the moment when those who are being expelled must hurriedly flee or purposefully vacate their homes, lands, and community. Migration takes place immediately following expulsion. The PTEs that forced these newly displaced persons to abandon property and possessions are vividly recalled and losses are acutely experienced during flight and migration. Transition and adaptation during initial relocation bring loss and radical change in lifestyle to the forefront, as recently displaced persons attempt to cope with losses while adjusting to urban living conditions, ill-equipped socially or vocationally to survive. Long-term resettlement involves modification of all aspects of life and lifestyle such as: learning to cope within urban systems, seeking support from various social services, generating meager income in informal sector jobs, and dealing with the stressors of pervasive urban violence. Least characterized is the return phase because so few Colombian IDPs have been able to successfully rejoin their communities of origin.

Trauma Signature Summary (Table 5)

Dating from the mid-1900s, the armed insurgency in Colombia has produced a multitude of consequences and created a spectrum of “victims of armed conflict” [48••], with the largest number of affected persons being IDPs [1••, 2••]. The TSIG summary table illustrates that internal displacement generates a confluence of major psychological risk factors that, singly and collectively, carry a high risk for psychopathology. The elements of (1) decades-long duration, (2) ever-enlarging numbers of persons affected, and (3) intentional human causation differentiate forced migration in Colombia from TSIG case studies of natural, hybrid, and non-intentional technological disasters previously performed [33–41]. These features also contribute to the finding that most psychological risk factors appearing in Table 5 are rated as either “very severe” or “extreme.”

Discussion

Forced Migration in Colombia within the International Context

Conflict-induced forced migration is an international public health crisis of such magnitude that it commands the dedicated focus of United Nations agencies and international monitoring centers (IDMC, Norwegian Refugee Council, International Organization on Migration) and takes high priority on the agendas of numerous humanitarian actors worldwide [7••, 10]. Globally, more than 48 million world citizens in dozens of nations are displaced from their homes and communities of origin because of armed conflict. The need for mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) for IDPs and refugees with elevated rates of distress, psychosocial needs, and CMDs is a critical component of the response to those who have been forced from their lands [3, 4••].

Colombia occupies a noteworthy place in the annals of forced migration [1••]. Colombian internal displacement has continued unabated for decades, and because very few IDPs are able to return to their communities of origin, the census rises annually. This has maintained Colombia's rank as either first or second in numbers of IDPs every year for the past decade, 2004-2013 (Table 1), despite dramatic, time-limited surges of IDP numbers in the world's fiercest combat zones [7••].

Landholding peasants have been expelled en masse, casualties of the armed conflict that, in recent years, has become increasingly financed by drug traffickers. Peasant lands are desirable for drug crop cultivation, drug processing, transit, concealment of illicit activities, and expansion of the power base for armed groups (including guerrilla, paramilitary, narco-traffickers, criminal bands). The seizure of agrarian lands from vulnerable “campesino” landholders partially explains the predominant rural-to-urban flow of IDPs. Recent years have seen a secondary pattern of urban-to-urban relocation as some resettled IDPs seek out new habitats.

Disproportionately represented among Colombian forced migrants are women and children, as well as indigenous, Afro-Colombian, and low literacy subgroups. IDPs settle on the outskirts of urban centers, occupying areas that are co-populated by a variety of “victims of armed conflict” and persons living in poverty. Colombian IDPs do not dwell in camps. There are no clear geographic boundaries designating IDP neighborhoods. Most IDPs (95 %) work in the “informal” sector, toiling in various forms of subsistence labor, earning undeclared wages, and receiving no employee benefits. Healthcare in Colombia is regarded as a universal “right,” but Colombia has a two-tiered healthcare delivery system (contributory and subsidized); without formal employment, the majority of IDPs do not qualify for the healthcare services provided to persons who are formally employed and pay taxes.

Many IDPs have been displaced by the decades-long armed insurgency that has created a changeable checkerboard of power throughout rural Colombia [1••, 2••]. Most IDPs are noncombatants who never engaged directly in any conflict. Nevertheless, the armed actors who expelled the IDPs also have a presence in the urban centers of relocation, so many resettled IDPs are fearful about publicizing their presence or their plight, preferring the safety of anonymity. With the recent passage of The Law of the Victims [48••], programs to provide public health, psychosocial, and legal services—and land restitution—for IDPs have been initiated. As such, there is now increasing incentive for IDPs to register and be counted. Hazards and Stressors Across the Phases of Conflict-induced Displacement

Each of the phases along the pathway of displacement is replete with stressors including exposure to various forms of violence. However, the prominence of exposures to hazards, losses, and life changes varies across phases. The expulsion phase, as well as pre-expulsion events that immediately precede displacement, frequently includes exposures to actual or threatened physical harm accompanied by perceived life threat. While acute and severe loss is powerfully felt at the moment of expulsion, loss continues to be experienced across all subsequent phases. Likewise, expulsion triggers abrupt change, but continuous change is a hallmark of life for IDPs. The remainder of this discussion traces the hazards and stressors encountered by IDPs along the trajectory of displacement, citing the Colombian and global research literature.

Pre-expulsion

Colombia

In rural Colombia, the stressors inherent in the “campesino” (peasant) lifestyle of subsistence agriculture have been exacerbated by decades of armed conflict that has created nearly universal exposure to violence. Much of Colombia remains outside the control and protection of the Colombian Army or National Police, while the geographic and economic hegemony of the various armed groups shifts amorphously and dynamically.

Typically, life for Colombian campesinos and small landholders prior to expulsion is persistently hazardous with exposure to the actions of multiple armed groups [12–16]. Many were overtly threatened (57 % of IDPs claim they abandoned their homes due to threats) and heavily taxed by the armed actors (essentially extortive payments to forestall physical harm or seizure of lands) [49–51]. Many have borne witness to warfare and a variety of atrocities taking place in the vicinity of their home communities [49–56]. Some of their neighbors may have lost their properties through legal processes to dispossess them, often involving bribes or other forms of misfeasance [1••, 16]. If local community members have joined the insurgency or engaged in illicit crop cultivation or drug trafficking, all local residents were placed at high risk when government forces launched combat operations or aerial spraying and defoliation [53–55].

International

The enlarging global research literature on conflict-associated forced displacement demonstrates that the pre-expulsion period sets the stage for later displacement [6, 57–66, 67•, 68••, 69–83]. Other nations where internal displacement has occurred within the context of enduring armed conflicts include Uganda [6, 62, 66], Ethiopia [57], Sudan [58, 59, 70, 72, 73, 79, 81], and Sri Lanka [71, 74]. Prior to displacement, future IDPs witness nearby armed conflict and other acts of violence [6, 67•, 68••, 69–77, 71, 74–78]. Additional pre-expulsion stressors include famine, poverty, and religious persecution and strife [57, 74, 83].

Departure/expulsion

Colombia

In Colombia, each episode of displacement is different, ranging in scale from a single individual or household to mass expulsion of entire communities [1••, 2••, 7••, 14]. The moment when persons must abandon their homes and communities is traumatically memorable and fraught with loss. The trigger event may be either preemptive avoidance of harm or direct infliction of harm. Some persons vacate their properties based on perceived or imminent threats. Others are violently forced from their lands.

The litany of atrocities that have precipitated displacement in Colombia includes the murder of relatives, massacres, forced disappearances, torture, kidnapping, assault, sexual abuse, and other forms of violence [1••, 2••, 12–19, 49, 51, 52, 84]. Beyond whatever harm is perpetrated, the expulsion phase is most notable for the gravity, totality, and finality of loss. At the instant of displacement, home, land, crops, livestock, and possessions are left behind [53, 85]. Loss extends to livelihood, means of support, stature and identity, self-sufficiency, reputation, stability, community connectedness, and social network destruction [55, 56, 85–88], collectively described as experiencing “life project loss” [89]. In Colombia there has been disproportionate displacement of indigenous peoples and obliteration of cultural roots in what has been termed the “depeasantization phenomenon” [55, 56, 85, 86].

International

From the international literature, the expulsion event has been variously set off by combat, killings, arrests, maltreatment, forced labor, torture, sexual violence, kidnapping, ethnic violence, and human rights abuses [57–66, 67•, 71, 77, 79, 80, 82, 90]. Expulsion frequently results in separation from family members and acute shortages of survival resources such as food and shelter [78, 79, 83, 91].

Migration

Colombia

The path, pace, and pattern of migration are highly variable. Some IDPs may be in pell-mell flight, escaping from a conflict zone. Others may initially travel a short distance to bivouac with extended family members or neighbors for a period before moving on to relocate elsewhere. For some, however, migration involves a dangerous and uncertain passage [50]. Most IDPs are noncombatants who are not enemies of the State, but much of Colombia is not securely under government control, and the tentacles of various armed actors are far reaching [1••]. Some recently displaced persons have been maintained under surveillance while migrating from their former homes to a distant point in search of refuge. Migrating IDPs may experience lack of basic necessities, exposure to the elements, vulnerability to robbery or physical harm while using public transportation, and then a disconcerting arrival in the destination city, devoid of urban survival skills.

International

International research describes multitudinous dangers experienced while migrating including physical exhaustion, lack of food and water, communicable disease risks, fleeing through combat zones, and witnessing harm to loved ones [57]. In contrast to the situation in Colombia, some nations have experienced conflict or genocidal actions on a scale that has set in motion mass migrations of 100,000s of persons simultaneously [76, 79]. Some migrations have resulted in high death rates from exposure, injury, bombardment, or armed assault [91]. Such “crisis migration” scenarios [92] are associated with shortages of survival necessities, inability to find suitable and sustainable areas for resettlement [76], overcrowding of IDP camps, and high rates of morbidity and mortality [6]. In some instances, migrating peoples, including unaccompanied and vulnerable minors, have had to rely on professional traffickers to reach their destinations [67•].

Transition and Adaptation to Relocation

Colombia

IDPs arriving in urban settings experience overwhelming “disorientation.” Displaced Colombians journey from what is customary to what is not even conceivable. Upon arrival in the urban destination city, every known thing from past existence is changed. New IDPs relocate to the poorest and most hazardous neighborhoods characterized by lack of sanitation, food insecurity, malnutrition, exposure to disease vectors, and environmental pollutants [49, 50, 93–97].

Some IDPs initially sleep in makeshift tents with minimal protection from the elements or urban predators. Moving from the street to a more stable but overcrowded physical structure often involves an entire family sharing a single room [49, 50, 93–95]. New IDPs have few prospects for employment and a limited repertoire of urban job skills [49, 50, 93, 95, 96], leading to economic dependence [85].

Pervasive exposure to violence, constant vulnerability to physical harm, and frequent victimization characterize life in the impoverished barrios populated by IDPs [98]. Gang activity is common. Colombian urban areas are carved into micro-territories with local control exerted by various guerrilla factions, narco-paramilitary gangs, or criminal bands (“BACRIM”). Some IDPs find themselves relocating in proximity to urban members of the armed groups that evicted them from their rural homes.

International

Globally, in tandem with the Colombian situation, IDPs experience a variety of exposures to violence upon initial relocation [63], and they must navigate daunting bureaucratic systems to seek refugee status or apply for asylum while confronting social, cultural, and language barriers [67•]. Studies have indicated that increased trauma exposure during expulsion is associated with worse economic, occupational, educational, and familial adaptation during relocation [76, 79]. For some forced migrants, the site of initial relocation is an IDP camp, typically characterized by overcrowding, insecurity, food aid dependency, health problems associated with lack of basic necessities, and exposure to camp violence [6, 99, 100].

Long-Term Resettlement

Colombia

Long-term resettlement represents the longest phase of displacement, typically persisting for decades. Children are born and raised in displacement and life in resettlement becomes the “new normal.”

Resettled IDPs face a variety stressors and challenges including low literacy, extreme poverty, employment in the informal sector, discrimination based on ethnicity, stigmatization based on IDP status, single-woman-headed households, and significant delays in qualifying for and receiving supportive services [49, 50, 53, 54, 87, 95–97, 101–103]. IDPs live in overcrowded “ollas urbanas” – marginalized urban areas characterized by drug micro-trafficking, prostitution, delinquency, and begging [53, 54, 87, 102]. Many live in congregate, shared spaces, lacking security and personal privacy.

Life in urban barrios populated by IDPs is replete with exposures to hazards such as gang violence, gender-based violence, partner/family violence, and school bullying. IDPs share neighborhoods with other “victims of armed conflict.” Shifting on a block-by-block basis, power and control are often vested in the hands of criminal bands, gang members, or even guerrilla or ex-paramilitary whose influence extends to urban settings [50].

The act of transitioning from rural to urban settings does not confer safety. IDPs do not find refuge or safe haven. For many IDPs, the major change is that in the urban areas of resettlement, they are no longer landholders and therefore not targets for expulsion. However, in the urban settings where IDPs relocate, dangers and psychological stressors abound.

International

The literature on long-term resettlement following displacement describes the hardships endured and the concomitant psychological consequences. Depending upon the locale and the conflict situation, IDPs experience impoverished living conditions characterized by overcrowding, lack of privacy, shared beds, exposure to animals and insect vectors, insecurity and vulnerability to violence, and scarcity of basic needs including nutritious food, drinking water, sanitation, and health care [57–60, 63, 64, 70, 72, 74, 75, 90]. Documented mental health problems associated with long-term resettlement include PTSD, depression, PTSD-depression comorbid diagnosis, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, somatoform disorder, somatic complaints, alcoholism, sleep disturbances, emotional reactivity, psychological distress, elevated suicide risk, perceived stigmatization, helplessness and guilt after witnessing violence, and long-term disability associated with mental health problems [3, 4••, 5, 6, 57–62, 67•, 68••, 69, 70, 73–75, 79, 82, 100]. Studies have revealed intergenerational transmission of trauma for children who are born to displaced families [74]. Also prominent are women's health issues including lack of sexual and reproductive rights and access to obstetrical and gynecological care [72].

Return to Community of Origin

Colombia

To this date most Colombian IDPs have not, and cannot, return to their communities of origin to reclaim their lands and homes. The Law of the Victims [48••] makes provision for restoration of property rights or compensation for losses. However, the current reality is that IDPs who attempt to return to their communities of origin face extreme risks for re-victimization including persecution, reprisals, and violence [49, 54, 93, 88].

As an important counterpoint, many Colombian IDPs have adapted to their urban environments of resettlement, and they do not express a wish to return. For them, “return” would feel like a second displacement experience. As a variation on this theme, increasingly, patterns of displacement within Colombia are transitioning to intra-urban relocation of IDPs, sometimes referred as “re-displacement” [104].

Conclusion

The experience of forced migration in Colombia involves a sequence of phases during which IDPs are subjected to a cascading series of PTEs. The trajectory of Colombian internal displacement, described as a concatenation of six stages, is protracted in time. At each stage, exposures to hazards are compounded with severe and irrecoverable losses, creating constant flux and change. IDPs must constantly adapt and attempt to cope with shifting realities at each step. This synergistic sequence of exposures portends a high incidence and prevalence of psychological consequences with a high likelihood for progression to diagnosable psychopathology. This has been robustly documented in the evolving scientific literature. In the present study, trauma signature analysis has been applied to provide a framework for understanding the dynamics of internal displacement in Colombia in relation to the psychological consequences observed.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Disaster Psychiatry

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest James M. Shultz, Dana Rose Garfin, Zelde Espinel, Ricardo Araya, Milton L. Wainberg, Roberto Chaskel, Silvia L. Gaviria, Anna E. Ordóñez, Maria Espinola, Fiona E. Wilson, Natalia Muñoz García, Ángela Milena Gómez Ceballos, Yanira Garcia-Barcena, Helena Verdeli, and Yuval Neria declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Dr. Maria A. Oquendo receives royalties for the commercial use of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Her family owns stock in Bristol Myers Squibb.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

James M. Shultz, Center for Disaster & Extreme Event Preparedness (DEEP Center), University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA

Dana Rose Garfin, Department of Psychology and Social Behavior, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA dgarfin@uci.edu.

Zelde Espinel, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, FL 33136, USA z.espinel@med.miami.edu.

Ricardo Araya, Centre for Global Mental Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK riaraya.psych@gmail.com.

Maria A. Oquendo, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University & The New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA mao4@columbia.edu

Milton L. Wainberg, Global Mental Health T32 Research Fellowship, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University & The New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA mlw35@columbia.edu

Roberto Chaskel, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, Hospital Militar Central, Universidad El Bosque, Universidad de Los Andes, Bogota, Colombia rchaskel@gmail.com.

Silvia L. Gaviria, Department of Psychiatry, Universidad CES, Medellín, Colombia sgaviria1@une.net.co

Anna E. Ordóñez, Child Psychiatry Branch, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)/National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA anna.ordonez@nih.gov

Maria Espinola, McLean Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA mfe@bu.edu.

Fiona E. Wilson, Department of Clinical & Health Psychology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK fiona.e.wilson@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk

Natalia Muñoz García, Program in Clinical and Health Psychology, School of Social Sciences, Universidad de Los Andes, Bogota, Colombia n.munoz12@uniandes.edu.co.

Ángela Milena Gómez Ceballos, Program in Public Health, Schools of Medicine and Government, Universidad de Los Andes, Bogota, Colombia am.gomez14@unandes.edu.co.

Yanira Garcia-Barcena, Department of Health Informatics, Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine, Louis Calder Memorial Library, Miami, FL, USA jennygarcia@miami.edu.

Helen Verdeli, Teachers College and Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University & The New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA verdeli@tc.edu.

Yuval Neria, Department of Psychiatry & Department of Epidemiology, Columbia University & The New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA ny126@columbia.edu.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1••.Shultz JM, Gómez Ceballos AM, Espinel Z, Rios Oliveros S, Fonseca MF, Hernandez Florez LH. Internal displacement in Colombia: fifteen distinguishing features. Disaster Health. 2014;2(1):1–12. doi: 10.4161/dish.27885. [Presents the defining characteristics of forced migration that differentiate Colombia from other nations with large populations of IDPs and refugees.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2••.Accion Social Informe Nacional de Desplazamieto Forzado en Colombia, 1985 a 2012. [31 May 2014];Accion Social: Unidad Para la Atencion y Reparacion Integral a Las Victimas. 2013 Jun; http://www.cjyiracastro.org.co/attachments/article/500/Informe%20de% 20Desplazamiento%201985-2012%20092013.pdf. [Provides a detailed and richly illustrated account of the current state of internal displacement in Colombia. Particularly useful for graphically demonstrating time trends and geographic patterns of displacement.]

- 3.Porter M, Haslan N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;294:602–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Roberts B, Browne J. A systematic review of factors influencing the psychological health of conflict-affected populations in low and middle-income countries. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(8):814–29. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2010.511625. [Provides a recent and well-formulated review of the international literature on psychological dimensions of conflict-affected populations worldwide with a strong focus on forced migrants.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, Marnane C, Bryant RA, van Ommeren M. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302(5):537–49. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts B, Ocaka KF, Browne J, Oyok T, Sondorp E. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression amongst internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7••.Albuja S, Arnaud E, Caterina M, Charron G, Foster F, Glatz AK, et al. Global overview 2014: people internally displaced by conflict and violence. [31 May 2014];Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and Norwegian Refugee Council, Geneva Switzerland. 2014 2014. http://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/2014/global-overview-2014-people-internally-displaced-by-conflict-and-violence/. [Provides the official global overview on internal displacement for 2013. Facilitates the positioning of IDP patterns within Colombia in relation to the international context.]

- 8.Albuja S, Arnaud E, Beytrison F, Caterina M, Charron G, Fruehauf U, et al. Global overview 2012: people internally displaced by conflict and violence. [31 May 2014];Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and Norwegian Refugee Council, Geneva Switzerland. 2013 http://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/global-overview-2012.

- 9.UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency [31 May 2014];Internally displaced people: questions and answers. 2007 http://www.unhcr.org/basics/BASICS/405ef8c64.pdf.

- 10.UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency [31 May 2014];UNHCR Statistical Yearbook 2012. (12th edition). 2012 http://www.unhcr.org/52a7213b9.html.

- 11••.United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance [31 May 2014];Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. 2004 https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/GuidingPrinciplesDispl.pdf. [Provides the definitive examination of refugee populations worldwide, thus permitting comparison of IDP vs. refugee situations.]

- 12.Habozit A, Moro MR. Breaking the silence in Colombia to resist violence, Part 1 of 2. Soins Psychiatrie. 2013;284:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Habozit A, Moro MR. Breaking the silence in Colombia to resist violence, Part 2 of 2. Soins Psychiatrie. 2013;285:40–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) and Norwegian Refugee Council [31 May 2014];Colombia: property restitution in sight but integration still distant: a profile of the internal displacement situation. 2011 Dec 29; http://www.rcusa.org/uploads/pdfs/Colombia+-December+2011.pdf.

- 15.Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières-Holland. [10 Jan 2014];Living in Fear: Colombia's Cycle of Violence. 2006 http://www.msf.org.au/resources/reports/report/article/living-in-fear-colombias-cycle-of-violence.html.

- 16.Three time victims: victims of violence, silence and neglect. Armed conflict and mental health in the department of Caquetá; Colombia: 2010. [7 July 2014]. Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières. http://www.lekari-bez-hranic.cz/cz/downloads/Three_time_victims.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres de Galvis Y, Bareño J, Sierra GM, Mejia R, Berbesi DY. Indicadores de situación de riesgo de salud mental población desplazada Colombia. Rev Observatorio Nac Salud Ment Colomb. 2010;1:26–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards A, Ospina-Duque J, Barrera-Valencia M, Escobar-Rincón J, Ardila-Gutiérrez M, Metzler T, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression symptoms, and psychosocial treatment needs in Colombians internally displaced by armed conflict: a mixed-method evaluation. Psychol Trauma. 2011;3:384–93. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Londoño A, Romero P, Casas G. The association between armed conflict, violence and mental health: a cross sectional study comparing two populations in Cundinamarca department, Colombia. Confl Health. 2012;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodríguez González A, Posada-Villa JA, Bayón Montaña MC, Pacheco JF. Intervención en Crisis Durante la Fase de Emergencia para Víctimas de Desplazamiento Forzado y Desastres: guía para Gestión de Caso Psicosocial Para Unidades Móviles. Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar and Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM); 2009. [7 Jul 2014]. http://www.oim.org.co/poblacion-desplazada/1466-intervencion-en-crisis-durante-la-fase-de-emergencia-guia-de-gestion-de-casospsicosocial-para-unidades-moviles.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 2005;365:1309–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Shultz JM, Neria Y. Trauma signature analysis: state of the art and evolving future directions. Disaster Health. 2013;1:4–8. doi: 10.4161/dish.24011. [Provides the overview on trauma signature (TSIG) analysis methods and applications.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shultz JM, Neria Y, Espinel Z, Kelly F. Trauma signature analysis: evidence-based guidance for disaster mental health response. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26(S1):s4. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X11006364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: part I. A review of the empirical literature, 1981-2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65(3):207–39. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norris FH, Friedman M, Watson P. 60,000 disaster victims speak. Part II. Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry. 2002;65:240–60. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norris FH, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. [31 Jan 2014];Risk factors for adverse outcomes in natural and human-caused disasters: a review of the empirical literature: a National Center for PTSD fact sheet. 2007 http://www.georgiadisaster.info/MentalHealth/MH12%20ReactionsafterDisaster/Risk%20Factors.pdf.

- 27.Norris FH, Wind LH. The experience of disaster: trauma, loss, adversities, and community effects. In: Neria Y, Galea S, Norris FH, editors. Mental health and disasters. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2009. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Posttraumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008;38:467–80. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shultz JM, Neria Y, Allen A, Espinel Z. Psychological impacts of natural disasters. In: Bobrowsky P, editor. Encyclopedia of natural hazards. Springer Publishing; New York: 2013. pp. 779–91. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shultz JM, Espinel Z, Galea S, Reissman DE. Disaster ecology: implications for disaster psychiatry. In: Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Weisaeth L, Raphael B, editors. Textbook of disaster psychiatry. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shultz JM. Perspectives on disaster public health and disaster behavioral health integration. Disaster Health. 2013;1:1–4. doi: 10.4161/dish.24861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shultz JM, Espinel Z, Flynn BW, Hoffman Y, Cohen RE. DEEP PREP: all-hazards disaster behavioral health training. Disaster Life Support Publishing; Tampa: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shultz JM, Marcelin LH, Madanes S, Espinel Z, Neria Y. The trauma signature: understanding the psychological consequences of the Haiti 2010 earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26:353–66. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X11006716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shultz JM, Marcelin LH, Espinel Z, Madanes SB, Allen A, Neria YA. Haiti earthquake 2010: psychosocial impacts. In: Bobrowsky P, editor. Encyclopedia of natural hazards. Springer Publishing; New York: 2013. pp. 419–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shultz JM, McLean A, Herberman Mash HB, Rosen A, Kelly F, Solo-Gabriele HM, et al. Mitigating flood exposure: reducing disaster risk and trauma signature. Disaster Health. 2013;1:30–44. doi: 10.4161/dish.23076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neria Y, Shultz JM. Mental health effects of Hurricane Sandy: characteristics, potential aftermath, and response. JAMA. 2012;308:2571–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.110700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shultz JM, Neria Y. The 2x2 Project. Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology; 2012. [7 Jul 2014]. The trauma signature of Hurricane Sandy: a meterological chimera. http://the2x2project.org/the-trauma-signature-of-hurricane-sandy/. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shultz JM, Walsh L, O'Sullivan T. Psychological impact of Superstorm Sandy: the trauma signature. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013;28(S1):s162. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shultz JM, Walsh L, Garfin DR, Wilson FE, Neria Y. The 2010 deepwater horizon oil spill: the trauma signature of an ecological disaster. J Behav Health Serv Res. :1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shultz JM, Forbes D, Wald D, Kelly F, Solo-Gabriele HM, Rosen A, et al. Trauma signature of the Great East Japan Disaster provides guidance for the psychological consequences of the affected population. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:201–14. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shultz JM, Kelly F, Forbes D, Leon GR, Verdeli H, Rosen A, et al. Triple threat trauma: evidence-based mental health response for the 2011 Japan disaster. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26:141–5. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X11006364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shultz JM, Cohen A. Sandy Hook Elementary school shooting: the trauma signature. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013;28(S1):s163. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Migline V, Shultz JM. Psychosocial impact of the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26(S1):s110. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Espinel Z, Shultz JM. Trauma exposure in internally displaced women in Colombia: psychological intervention. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013;28(S1):s167. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Espinel Z, Shultz JM, Araya R, Hernandez Florez LJ, Gomez Ceballos AM, Verdeli H, et al. OSITA: “Outreach, Screening, and Intervention for Trauma” with internally displaced women in Bogotá, Colombia.. In: Javits Jacob K., editor. Presented at: American Psychiatric Association 167th Annual Meeting; New York, NY, USA. 3 May 2014; Convention Center; [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters [31 May 2014];EM-DAT: the international disaster database. http://www.emdat.be.

- 47.Health disaster management: guidelines for evaluation and research [31 May 2014];World Association of Disaster and Emergency Medicine (WADEM) http://www.wadem.org/guidelines.html.

- 48••.Ley de víctimas y restitución de tierras y sus decretos reglamentarios: LEY 1448 de 2011. [31 May 2014];Republica de Colombia, Ministerio del Interior. 2012 http://portalterritorial.gov.co/apcaa-files/40743db9e8588852c19cb285e420affe/ley-de-victimas-1448-y-decretos.pdf. [Presents the text of the landmark Law 1448: Law of the Victims and Land Restitution, passed in 2011, that defines IDPs as a class of “victims of armed conflict” and lays out a comprehensive set of program strategies to serve IDPs and prepare the way for some to return to communities of origin.]

- 49.Población desplazada en Bogotá, una responsabilidad de todos. Colombia: 2013. Proyecto Bogotá Cómo Vamos y Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados [ACNUR]. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ceballos Bedoya M. El desplazamiento forzado en Colombia y su ardua reparación. Rev Iberoam Filosofía Política Humanidades. 2013;15:169–88. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garay L. Tragedia humanitaria del desplazamiento forzado en Colombia. Estud Políticos. 2009;35:153–77. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alejo E, Rueda G, Ortega M, Orozco LC. Estudio epidemiológico del trastorno por estrés postraumático en población desplazada. Univ Psychol. 2007;6:623–35. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andrade AJ. Psychopathological effects of Colombian armed conflict on forcibly displaced families resettled in Cairo, 2008. Rev ORBIS. 2011;20:111–48. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boletín “Tapando el sol con las manos”. [9 Jul 2014];Informe sobre el desplazamiento forzado, conflicto armado y derechos humanos, periodo enero-junio. 2008 http://www.abcolombia.org.uk/downloads/Tapando_el_sol_con_los_manos.pdf.

- 55.CODHES Boletín “Víctimas emergentes”. [9 Jul 2014];Informe sobre el desplazamiento, derechos humanos y conflicto armado en 2008. 2009 http://www.colectivodeabogados.org/IMG/pdf/codhes_informa_no_75.pdf.

- 56.Falla U, Chávez YA, Molano G. Desplazamiento forzado en Colombia: análisis documental e informe de investigación en la Unidad de Atención Integral al Desplazado (UAID). Rev Tabula Rasa. 2003;001:221–34. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Araya M, Chotai J, Komproe IH, de Jong JTVM. Effect of trauma on quality of life as mediated by mental distress and moderated by coping and social support among postconflict displaced Ethiopians. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:915–27. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ayazi T, Lien L, Eide AH, Ruom MM, Hauff E. What are the risk factors for the comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in a war-affected population? A cross-sectional community study in South Sudan. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ayazi T, Lien L, Eide A, Swartz L, Hauff E. Association between exposure to traumatic events and anxiety disorders in a post-conflict setting: a cross-sectional community study in South Sudan. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bamrah S, Mbithi A, Mermin JH, Boo T, Bunnell RE, Sharif SK, et al. The impact of post-election violence on HIV and other clinical services and on mental health—Kenya, 2008. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013;28:43–51. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12001665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Basishvili T, Eliozishvili M, Maisuradze L, Lortkipanidze N, Nachkebia N, Oniani T, et al. Insomnia in a displaced population is related to war-associated remembered stress. Stress Health. 2012;28:186–92. doi: 10.1002/smi.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, Brennan RT, Verdeli H, Borisova I, Neugebauer R, et al. Moderators of treatment effectiveness for war-affected youth with depression in Northern Uganda. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:544–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Jong K, van der Kam S, Ford N, Hargreaves S, van Oosten R, Cunningham D, et al. The trauma of ongoing conflict and displacement in Chechnya: quantitative assessment of living conditions, and psychosocial and general health status among war displaced in Chechnya and Ingushetia. Confl Health. 2007;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-1-4. doi:10.1186/1752-1505-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Jong K, van de Kam S, Ford N, Lokuge K, Fromm S, van Galen R, et al. Conflict in the Indian Kashmir Valley II: psychosocial impact. Confl Health. 2008;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-2-11. doi:10.1186/1752-1505-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Jong K, Ford N, van de Kam S, Lokuge K, Fromm S, van Galen R, et al. Conflict in the Indian Kashmir Valley I: exposure to violence. Confl Health. 2008;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-2-10. doi:10.1186/1752-1505-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ertl V, Pfeiffer A, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Community-implemented trauma therapy for former child soldiers in Northern Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306:503–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67•.Fazel M, Reed RV, Panter-Brick C, Stein A. Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: risk and protective factors. Lancet. 2012;379:266–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60051-2. [Reviews mental health of refugee children resettled in high-income countries.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68••.Flink IJE, Restrepo M, Blanco DP, Ortegon MM, Enriquez CL, Beirens TMJ, et al. Mental health of internally displaced preschool children: a cross-sectional study conducted in Bogota, Colombia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:917–26. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0611-9. doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0611-9. [Examines the mental health impact of internal displacement specifically for preschool children in Bogotá.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Freitag S, Braehler E, Schmidt S, Glaesmer H. The impact of forced displacement in World War II on mental health disorders and health-related quality of life in late life: a German population-based study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:310–9. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hamid AARM Musa SA. Mental health problems among internally displaced persons in Darfur. Int J Psychol. 2010;5:278–85. doi: 10.1080/00207591003692620. doi:10.1080/00207591003692620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Husain F, Anderson M, Cardozo BL, Becknell K, Blanton C, Araki D, et al. Prevalence of war-related mental health conditions and association with displacement status in postwar Jaffna District, Sri Lanka. JAMA. 2011;306:522–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim G, Torbay R, Lawry L. Basic health, women's health, and mental health among internally displaced persons in Nyala Province, South Darfur, Sudan. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:353–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.073635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Salah TT, Abdelrahman A, Lien L, Eide AH, Martinez P, Hauff E. The mental health of internally displaced persons: an epidemio-logical study of adults in two settlements in Central Sudan. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59:782–8. doi: 10.1177/0020764012456810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Siriwardhana C, Adikari A, Pannala G, Siribaddana S, Abas M, Sumathipala A, et al. Prolonged internal displacement and common mental disorders in Sri Lanka: the COMRAID study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064742. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thapa SB, Hauff E. Psychological distress among displaced persons during an armed conflict in Nepal. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:672–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0943-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Letica-Crepulja M, Salcioglu E, Francisković T, Basoglu M. Factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in war-survivors displaced in Croatia. Croat Med J. 2011;52(6):709–17. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2011.52.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mels C, Derluyn I, Broekaert E, Rosseel Y. The psychological impact of forced displacement and related risk factors on Eastern Congolese adolescents affected by war. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:1096–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pedersen D, Tremblay J, Errázuriz C, Gamarra J. The sequelae of political violence: assessing trauma, suffering and dislocation in the Peruvian highlands. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:205–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roberts B, Damundu E, Lomoro O, Sondorp E. Post-conflict mental health needs: a cross-sectional survey of trauma, depression and associated factors in Juba, Southern Sudan. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-7. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schmidt M, Kravic N, Ehlert U. Adjustment to trauma exposure in refugee, displaced, and non-displaced Bosnian women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:269–76. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sonderegger R, Rombouts S, Ocen B, McKeever RS. Trauma rehabilitation for war—affected persons in northern Uganda: a pilot evaluation of the EMPOWER programme. Brit J Psychol. 2011;50:234–49. doi: 10.1348/014466510X511637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weaver H, Roberts B. Drinking and displacement: a systematic review of the influence of forced displacement on harmful alcohol use. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:2340–55. doi: 10.3109/10826081003793920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamout R, Chaaya M. Individual and collective determinants of mental health during wartime. A survey of displaced populations amidst the July–August 2006 war in Lebanon. Glob Public Health. 2011;6:354–70. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2010.494163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.CODHES [9 Jul 2014];Boletín especial “Las cifras no cuadran”; personas muertas, capturadas, heridas, secuestradas y desplazadas en el marco de la política de seguridad ciudadana en Colombia, periodo 2002 – septiembre 2008. 2008 http://viva.org.co/cajavirtual/svc0143/articulo0014.pdf.

- 85.Gómez SL, Botero MI, Rincón JC. El caso del desplazamiento forzado en Colombia: un análisis municipal a partir de regresiones cuantílicas. Equidad Desarro. 2013;19:77–96. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Centro Internacional de Toledo para la Paz CITpax Colombia. [9 Jul 2014];La Reparación Integral de las Víctimas en 2011, V Informe. 2012 http://www.aecid.org.co/?idcategoria=1786.

- 87.Aparicio DP, Di-Coloredo CA. Diferencias existentes en los estilos de afrontamiento de hombres y mujeres ante la situación de desplazamiento. [7 Jul 2014];Universidad de San Buenaventura. 2006 http://biblioteca.usbbog.edu.co:8080/Biblioteca/BDigital/36734.pdf.

- 88.Camilo GA. Impacto psicológico del desplazamiento forzoso: estrategia de intervención. In: Bellow MN, Cardinal EM, Arias FJ, editors. Efectos psicosociales y culturales del desplazamiento. Universidad Nacional de Colombia; Bogata: 2000. pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 89.CODHES . Desplazamiento forzado intraurbano y soluciones duraderas: una aproximación desde los casos de Buenaventura, Tumaco y Soacha. Bogotá: 2013. [7 Jul 2014]. Available at: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Desplazamiento%20forzado%20intraurbano%20y%20soluciones%20duraderas.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Turnip SS, Hauff E. Household roles, poverty and psychological distress in internally displaced persons affected by violent conflicts in Indonesia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:997–1004. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Somasundaram D. Collective trauma in the Vanni-a qualitative inquiry into the mental health of the internally displaced due to the civil war in Sri Lanka. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2010;4:1–31. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martin S, Weerasinghe S, Taylor A. What is crisis migration? [7 Jul 2014];Forced migration review. 2014 45:5–9. http://www.fmreview.org/en/crisis/martin-weerasinghe-taylor.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Balladelli PR, Rodríguez CY, Hernández J. Organización Panamericana de la Salud/Organización Mundial de la Salud: Ruta y Siga: Acceso de la Población Desplazada a los Servicios de Salud. OPS. Serie Cuadernos de Sistematización de Buenas Prácticas en Salud Pública en Colombia; Bogotá: 2009. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hernandez A, Gutierrez M. Vulnerability and exclusion: life conditions, health situation, and access to health services of the population displaced by violence settled in Bogotá – Colombia. Rev Gerencia Políticas Salud. 2008;7:145–76. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Builes GME, Gilberto MAA, Minayo MC. Las migraciones forzadas por la violencia: el caso de Colombia. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2005;13(5):1649–60. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232008000500028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]