Abstract

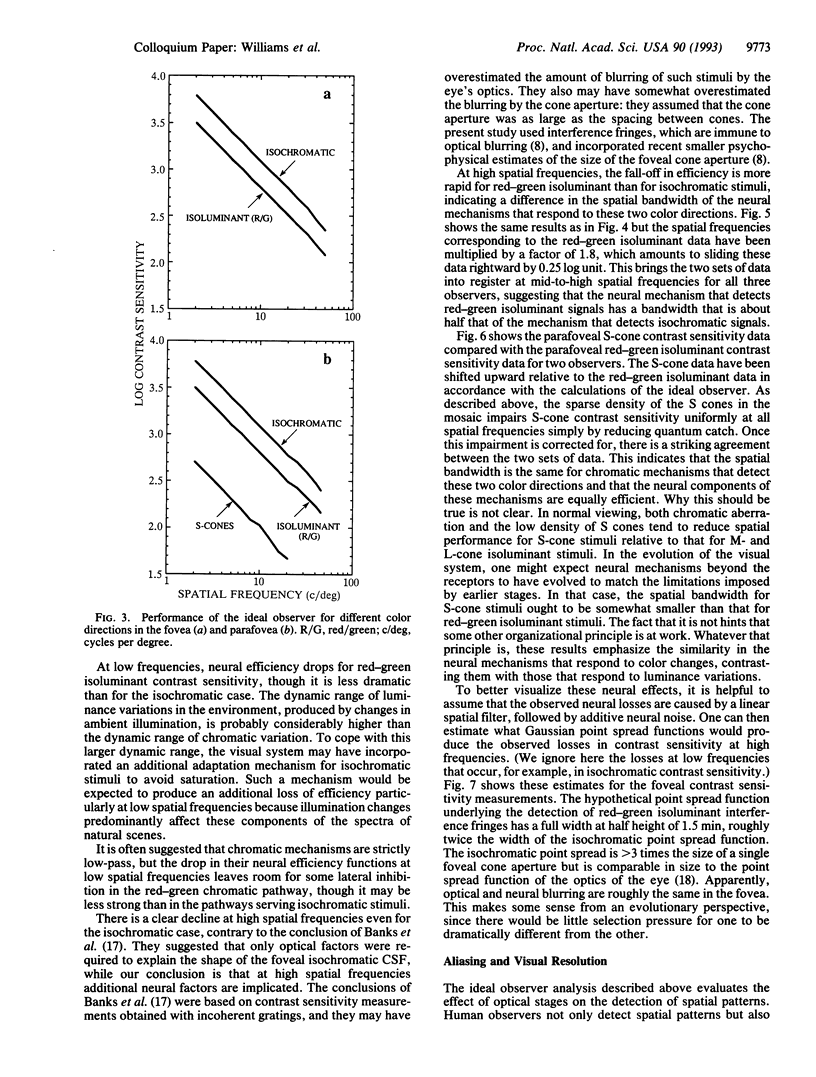

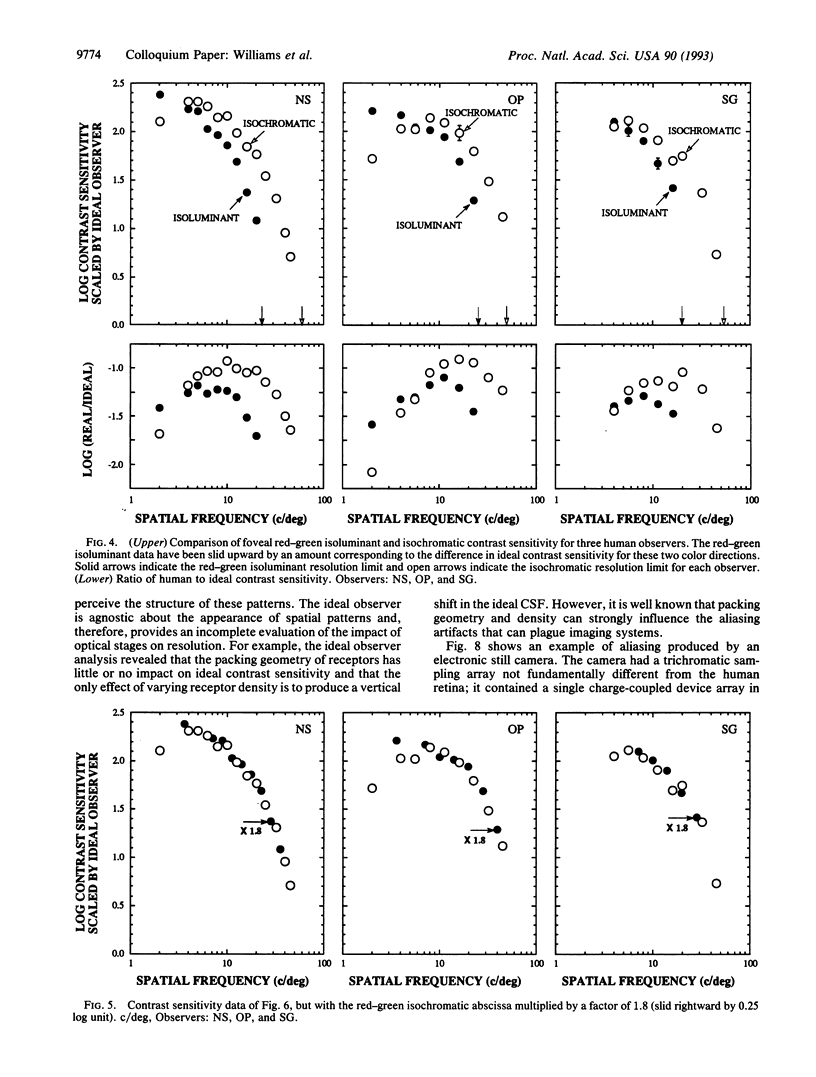

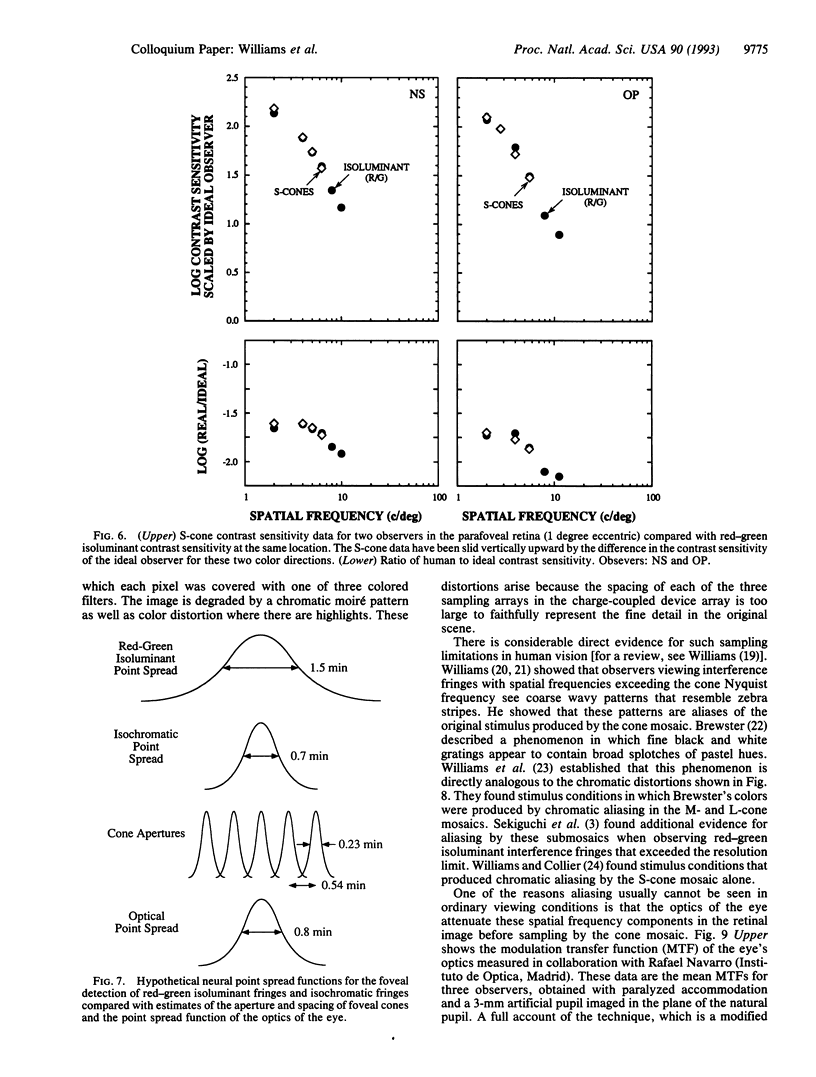

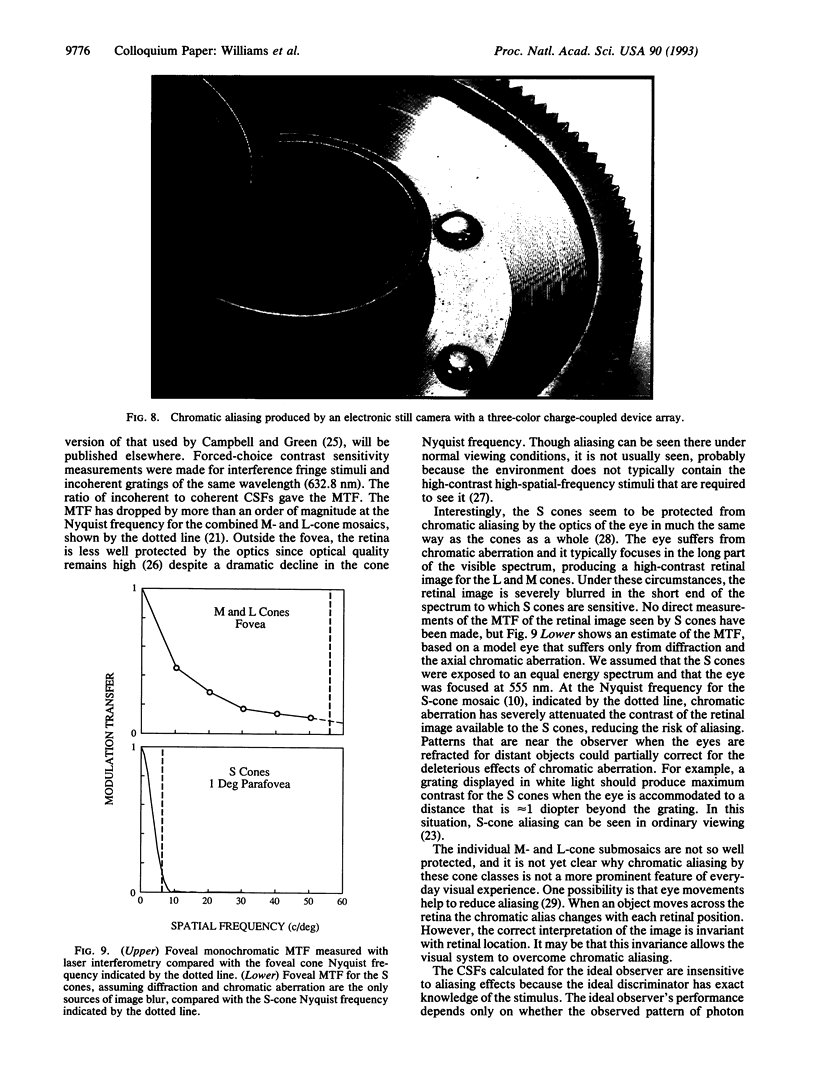

This paper evaluates the role of various stages in the human visual system in the detection of spatial patterns. Contrast sensitivity measurements were made for interference fringe stimuli in three directions in color space with a psychophysical technique that avoided blurring by the eye's optics including chromatic aberration. These measurements were compared with the performance of an ideal observer that incorporated optical factors, such as photon catch in the cone mosaic, that influence the detection of interference fringes. The comparison of human and ideal observer performance showed that neural factors influence the shape as well as the height of the foveal contrast sensitivity function for all color directions, including those that involve luminance modulation. Furthermore, when optical factors are taken into account, the neural visual system has the same contrast sensitivity for isoluminant stimuli seen by the middle-wavelength-sensitive (M) and long-wavelength-sensitive (L) cones and isoluminant stimuli seen by the short-wavelength-sensitive (S) cones. Though the cone submosaics that feed these chromatic mechanisms have very different spatial properties, the later neural stages apparently have similar spatial properties. Finally, we review the evidence that cone sampling can produce aliasing distortion for gratings with spatial frequencies exceeding the resolution limit. Aliasing can be observed with gratings modulated in any of the three directions in color space we used. We discuss mechanisms that prevent aliasing in most ordinary viewing conditions.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BRINDLEY G. S. The summation areas of human colour-receptive mechanisms at increment threshold. J Physiol. 1954 May 28;124(2):400–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks M. S., Geisler W. S., Bennett P. J. The physical limits of grating visibility. Vision Res. 1987;27(11):1915–1924. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor D. A., Nunn B. J., Schnapf J. L. Spectral sensitivity of cones of the monkey Macaca fascicularis. J Physiol. 1987 Sep;390:145–160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell F. W., Green D. G. Optical and retinal factors affecting visual resolution. J Physiol. 1965 Dec;181(3):576–593. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavonius C. R., Estévez O. Contrast sensitivity of individual colour mechanisms of human vision. J Physiol. 1975 Jul;248(3):649–662. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Makous W., Williams D. R. Serial spatial filters in vision. Vision Res. 1993 Feb;33(3):413–427. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90095-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio C. A., Allen K. A., Sloan K. R., Lerea C. L., Hurley J. B., Klock I. B., Milam A. H. Distribution and morphology of human cone photoreceptors stained with anti-blue opsin. J Comp Neurol. 1991 Oct 22;312(4):610–624. doi: 10.1002/cne.903120411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin S. J., Williams D. R. No aliasing at edges in normal viewing. Vision Res. 1992 Dec;32(12):2251–2259. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler W. S. Sequential ideal-observer analysis of visual discriminations. Psychol Rev. 1989 Apr;96(2):267–314. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.96.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. G. The contrast sensitivity of the colour mechanisms of the human eye. J Physiol. 1968 May;196(2):415–429. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan J. R., 3rd, Geisler W. S., Bovik A. C. Color as a source of information in the stereo correspondence process. Vision Res. 1990;30(12):1955–1970. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(90)90015-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauskopf J., Williams D. R., Heeley D. W. Cardinal directions of color space. Vision Res. 1982;22(9):1123–1131. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod D. I., Williams D. R., Makous W. A visual nonlinearity fed by single cones. Vision Res. 1992 Feb;32(2):347–363. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen K. T. The contrast sensitivity of human colour vision to red-green and blue-yellow chromatic gratings. J Physiol. 1985 Feb;359:381–400. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro R., Artal P., Williams D. R. Modulation transfer of the human eye as a function of retinal eccentricity. J Opt Soc Am A. 1993 Feb;10(2):201–212. doi: 10.1364/josaa.10.000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi N., Williams D. R., Brainard D. H. Aberration-free measurements of the visibility of isoluminant gratings. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 1993 Oct;10(10):2105–2117. doi: 10.1364/josaa.10.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi N., Williams D. R., Brainard D. H. Efficiency in detection of isoluminant and isochromatic interference fringes. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 1993 Oct;10(10):2118–2133. doi: 10.1364/josaa.10.002118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder A. W., Miller W. H. Photoreceptor diameter and spacing for highest resolving power. J Opt Soc Am. 1977 May;67(5):696–698. doi: 10.1364/josa.67.000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromeyer C. F., 3rd, Kranda K., Sternheim C. E. Selective chromatic adaptation at different spatial frequencies. Vision Res. 1978;18(4):427–437. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(78)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. Aliasing in human foveal vision. Vision Res. 1985;25(2):195–205. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Collier R. Consequences of spatial sampling by a human photoreceptor mosaic. Science. 1983 Jul 22;221(4608):385–387. doi: 10.1126/science.6867717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., MacLeod D. I., Hayhoe M. M. Foveal tritanopia. Vision Res. 1981;21(9):1341–1356. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., MacLeod D. I., Hayhoe M. M. Punctate sensitivity of the blue-sensitive mechanism. Vision Res. 1981;21(9):1357–1375. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. Topography of the foveal cone mosaic in the living human eye. Vision Res. 1988;28(3):433–454. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(88)90185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. Visibility of interference fringes near the resolution limit. J Opt Soc Am A. 1985 Jul;2(7):1087–1093. doi: 10.1364/josaa.2.001087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellott J. I., Jr Spectral analysis of spatial sampling by photoreceptors: topological disorder prevents aliasing. Vision Res. 1982;22(9):1205–1210. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellott J. I., Jr Spectral consequences of photoreceptor sampling in the rhesus retina. Science. 1983 Jul 22;221(4608):382–385. doi: 10.1126/science.6867716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]