Summary

Glucosylceramides (GlcCer), glucose-conjugated sphingolipids, are major components of the endomembrane system and plasma membrane in most eukaryote cells. Yet, the quantitative significance and cellular functions of GlcCer are not well characterized in plants and other multi-organ eukaryotes. To address this, we examined Arabidopsis lines lacking or deficient in GlcCer by insertional disruption or by RNAi suppression of the single gene for GlcCer synthase (GCS, At2g19880), the enzyme that catalyzes GlcCer synthesis. Null mutants for GCS (designated “gcs-1”) were viable as seedlings, albeit strongly reduced in size, and failed to develop beyond the seedling stage. Heterozygous plants harboring the insertion allele exhibited reduced transmission through the male gametophyte. Undifferentiated calli generated from gcs-1 seedlings and lacking GlcCer proliferated in a manner similar to calli from wild-type plants. However, gcs-1 calli, in contrast to wild-type calli, were unable to develop organs on differentiation media. Consistent with a role for GlcCer in organ-specific cell differentiation, calli from gcs-1 mutants formed roots and leaves on media supplemented with the glucosylated sphingosine glucopsychosine, which was readily converted to GlcCer independent of GCS. Underlying these phenotypes, gcs-1 cells had altered Golgi morphology and fewer cisternae per Golgi apparatus relative to wild-type cells, indicative of protein trafficking defects. Despite seedling lethality in the null mutant, GCS RNAi suppression lines with ≤2% of wild-type GlcCer levels were viable and fertile. Collectively, these results indicate that GlcCer are essential for cell-type differentiation and organogenesis, and plant cells produce GlcCer amounts in excess of that required for normal development.

Keywords: glucosylceramide synthase, glucosylceramide, sphingolipids, Arabidopsis, ceramide, differentiation

Introduction

Sphingolipids are essential membrane constituents in plants and other eukaryotes (Chen et al. 2012, Hillig et al. 2003, Leipelt et al. 2001). The functions of glycosphingolipids, consisting of non-polar ceramides linked to a variety of sugar residues, are not well understood in plants or animals at the organismal level. In plant cells, glycosphingolipids are abundant in the plasma membrane, and are found predominantly in the outer leaflet (Tjellstrom et al. 2010). They are also enriched in the tonoplast and other endomembranes (Lynch et al. 1987, Sperling et al. 2005, Verhoek et al. 1983), and several studies have implicated glycosphingolipids in targeting of proteins to the plasma membrane (Markham et al. 2011, Roudier et al. 2010, Yang et al. 2013). Glycosphingolipids, along with sterols, are major constituents of lipid rafts that are thought to form organizational units for proteins having cell surface-related activities, such as transporters (e.g., PIN1, H+-ATPase) and cell wall biosynthesis and degradative enzymes (Borner et al. 2005, Guillier et al. 2014, Simon-Plas et al. 2011, Titapiwatanakun et al. 2009). Glycosphingolipids also contribute to physical properties of the plasma membrane and tonoplast that are critical for plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (Kimberlin et al. 2013, Leipelt, et al. 2001).

Two classes of glycosphingolipids occur in plants: glucosylceramides (GlcCer) and glycosylinositolphosphoceramides (GIPC) (Chen et al. 2010). GlcCer consist of a glucose head-group bound to a ceramide backbone, and GIPC contain a head-group composed of phosphoinositol with up to seven hexose or pentose sugar residues bound to ceramide (Cacas et al. 2013). GIPC and GlcCer account for ~60% and ~30%, respectively, of the total sphingolipids of Arabidopsis leaves (Markham et al. 2007, Markham et al. 2006), and may occur in at least equivalent amounts in leaf tissues from tomato and soybean (Markham, et al. 2006).

In contrast to GIPC, which are primarily limited to plants and fungi, GlcCer are found broadly in the eukaryotes, including plants, insects, mammals, and most fungi. GlcCer are formed by activity of an evolutionarily conserved glucosylceramide synthase (GCS) that catalyzes the transfer of Glc from UDP-Glc to ceramide (Fig. 1a). It has also been shown that steryl glucosides can serve as the Glc donor for GlcCer synthesis in wax bean microsomes (Lynch et al. 1997), but it is not clear if this activity is catalyzed by the evolutionarily conserved GCS. In plants, GCS is ER-localized, along with enzymes associated with synthesis of the ceramide backbone (Hillig, et al. 2003, Leipelt, et al. 2001, Markham et al. 2013).

Figure 1. Characterization of the SK-2634 T-DNA insertion line and genetic complementation with GCS.

(a) GCS catalyzes the final step in GlcCer synthesis by transferring a glucosyl residue from UDP-Glc to the ceramide backbone. (b) Schematic of GCS/At2g19880 gene with 14 exons (black boxes) and 13 introns (white boxes). The SK-2634 mutant line has a T-DNA insertion in intron 9. (c) Two-week-old segregating SK-2634 line with gcs-1 (red arrows) exhibiting dwarfism and growth delay. (d) Wild-type (Col-0) calli and (e) gcs-1 calli propagated and maintained for four weeks on media supplemented with 0.2 mg/L 2,4-D and 2 mg/L kinetin. (f) Comparison of the GlcCer content in WT and gcs-1 seedlings and calli. Averages and standard errors, as indicated by error bars, are shown for three independent experiments. (g) Genetic complementation of gcs-1 with GCS allele. GCS gene amplified using WT genomic DNA shows ~6 Kbp band, while complemented line (expressing the transformed GCS cassette of ~5 Kbp) lacks this PCR product indicating a homozygous gcs-1 background (primers P10–P11; Table S1). FLC/At5g10140 gene was amplified as control (primers P12–P13; Table S1). Two-week-old (h) WT seedlings and (i) Complemented lines (T3) expressing WT GCS in the gcs-1 background.

At the whole organism level, complete disruption of a GCS-encoding gene has only been reported in filamentous fungi. In general, fungal gcs mutants are viable, but exhibit a number of growth defects. For example, loss of GlcCer in gcs mutants alters cell surface interactions of several fungal species with certain plant antifungal defensins (Ramamoorthy et al. 2007, Thevissen et al. 2004). In the case of a Fusarium graminearum gcs mutant, resistance to the alfalfa defensin MsDef1 was associated with impaired polar growth, due in part to the loss of aerial hyphae (Ramamoorthy, et al. 2007). Conidia of this mutant were also reduced in number and morphology. Similarly, pathogenicity of Candida albicans was lost in gcs mutants, although the cells were able to transition from the yeast to hyphal state (Noble et al. 2010).

In humans, the aberrant accumulation of GlcCer in organs such as spleen and liver is the basis for Gaucher’s disease, a human lysosomal disorder, and inhibitors of GCS have been explored as therapies for this disease (Messner et al. 2010). Conversely, the reduction of GlcCer activity by use of the GCS inhibitor D,L-threo-1-phenyl-2-palmitoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol (PDMP) has been shown to stimulate autophagy in neuronal cells and disrupt Golgi morphology and retrograde trafficking between the Golgi and ER (Shen et al. 2014). In addition, ceramide glycosylation is associated with maintaining the tumor pluripotency of breast cancer stem cells (Gupta et al. 2012). One hypothesis is that glycosylation of ceramides removes these from the stress-response pool, making selected cancer cells less responsive to chemotherapy. Fitting with this idea, it was shown that GCS is overexpressed in chemotherapy-resistant tumors of breast, colon, and leukemia cancers (Liu et al. 2013).

Similar to results in human cells, application of the GCS inhibitor PDMP to tobacco leaves and Arabidopsis roots was shown to result in disruption of Golgi complex morphology and Golgi-mediated protein trafficking, rapid fusion of vacuoles, and tonoplast invagination (Kruger et al. 2012, Melser et al. 2010). Defects in Golgi-mediated protein trafficking were accentuated by combining PDMP with GCS RNAi suppression. As observed in human cells, these defects included a decrease in retrograde trafficking from Golgi to ER as well as reduced expression of PIN1 in the plasma membrane and other subcellular compartments (Melser, et al. 2010, Melser et al. 2011). No impact on plant growth was reported for GCS RNAi lines, although the plants contained 30% to 50% of wild-type GlcCer levels suggesting only partial suppression of GCS (Melser, et al. 2011). As with the use of any chemical inhibitor for study of biological processes, it cannot be excluded that some portion of the phenotypes observed with PDMP treatment are the result of non-specific effects of this chemical, apart from inhibition of GCS activity.

Given the abundance of GlcCer in the plasma membrane and other endomembranes, we hypothesized that GlcCer are essential for cell and whole plant viability. To test this hypothesis, a gcs-1 T-DNA insertion mutant as well as GCS RNAi lines were examined for the impact of complete and partial loss of GCS activity in Arabidopsis. We show that plants with as little as 2% of wild-type GlcCer levels are viable, and cells can proliferate in a largely undifferentiated state (e.g., calli) without detectable amounts of GlcCer. However, nearly complete loss of GlcCer results in impaired cell-type differentiation and organogenesis in gcs-1 null mutant cells, a phenotype that was rescued by application of glucopsychosine, a glucosylated sphingosine, to restore GlcCer production independent of GCS activity. The subcellular basis for the gcs-1 phenotypes was shown to be associated with abnormal morphologies of several features, most notably the trans-Golgi network, indicative of defective protein processing through the secretory pathway. The results are discussed in light of the various roles of GlcCer in plant cells.

Results

A GCS null mutant displays seedling lethality but is viable as undifferentiated cells

Based on sequence similarity, At2g19880 is the only detectable candidate for glucosylceramide synthase (GCS) in the Arabidopsis genome. The corresponding cDNA encodes a ~59 kDa enzyme that has been shown to exhibit GCS activity (Melser, et al. 2010). An insertional mutant was obtained to better understand GCS function and its role in sphingolipid metabolism. SK-2634 line from the Saskatoon Arabidopsis mutant collection (Robinson et al. 2009b) was confirmed to have a T-DNA insertion in intron 9 of GCS (Fig. 1b). Mutants heterozygous (GCS/gcs-1) for the T-DNA insertion were identified by PCR-based genotyping (Fig. S1), and gcs-1 homozygous mutants obtained as segregants lacked detectable GCS mRNA transcripts (Fig. S2). gcs-1 seedlings were easily distinguished from wild-type and GCS/gcs-1 heterozygotes by their reduced size and pale, often necrotic appearance. These seedlings also displayed little secondary growth and did not advance past the seedling stage (Fig. 1c, 2a–f). Genetic complementation of gcs-1 by transgenic expression of the wild-type GCS allele restored mutant plants to growth indistinguishable from wild-type plants (Fig. 1g–i). Despite the apparent seedling lethality associated with GCS disruption, calli could be propagated from the gcs-1 seedlings and maintained as proliferating cells for periods of up to 8 weeks on sucrose-containing media (Fig. 1d, e). Consistent with disruption of the GCS enzyme, only trace amounts (≤0.05 nmol/g DW) of GlcCer were detectable in gcs-1 calli, whereas calli derived from wild-type seedlings contained ~150 nmol/g of GlcCer (Fig. 1f).

Figure 2. Seedling phenotypes from gcs-1 mutants.

Arabidopsis seedlings were imaged at three weeks post germination. (a) Wild-type (WT) seedlings have long roots and trichomes form on first and second leaves. Cotyledons and leaves are green. (b–f) The gcs-1 homozygous mutants display extreme dwarfism with short roots and malformed cotyledons, and are developmentally delayed. Phenotypes are variable, ranging from (b) severely dwarfed to (c) larger seedlings with first leaves. (d–f) Most seedlings exhibit pale and/or necrotic tissue. (e, f) Seedlings typically abort growth when first leaves can be seen emerging from the shoot apical meristem. Arrow marks first leaves in (f).

The gcs-1 mutation affects male gametogenesis

Since GlcCer are highly enriched in pollen from Arabidopsis (Luttgeharm et al. 2015b), gcs-1 mutants were examined for defects related to fertility. GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous plants are expected to produce 25% homozygous offspring. However, only ~9% of progeny displayed the mutant seedling phenotype, and the observed deficit in mutants could not be attributed to inefficient germination (Table 1). Reciprocal crosses of heterozygotes with wild-type showed that when GCS/gcs-1 was the female parent, the expected 1:1 ratio of heterozygous to wild-type progeny was observed, while when GCS/gcs-1 was the male parent, heterozygous progeny were significantly underrepresented (Table 2). Crosses were repeated using a GCS/gcs-1 line that was homozygous for two unlinked markers. With GCS/gcs-1 as the male parent, poor transmission of the gcs-1 allele was again observed (Table 2). These offsprings were heterozygous for the two control markers, confirming that pollination from the GCS/gcs-1 male parent had occurred.

Table 1. Occurrence of gcs-1 mutant phenotype from GCS/gcs-1 self-fertilization.

The numbers of observed progeny phenotypes were tallied from wild-type (WT) and four heterozygous plants (A–D). The gcs-1 mutant phenotypes were observed as shown in Figure 2. The numbers of seedlings that fail to germinate do not account for the observed frequency of the gcs-1 mutant phenotype below the expected 25%.

| Genotype of parent | WT | Mutant | Failure to germinate | Total | % Mutant | % No germination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 180 | 0 | 0 | 180 | 0 | 0 |

| GCS/gcs-1 A | 181 | 19 | 2 | 202 | 9.4 | 1.0 |

| GCS/gcs-1 B | 178 | 18 | 1 | 197 | 9.1 | 0.5 |

| GCS/gcs-1 C | 115 | 15 | 3 | 133 | 11.3 | 2.3 |

| GCS/gcs-1 D | 315 | 30 | 5 | 350 | 8.6 | 1.4 |

| GCS/gcs-1 Total | 789 | 82 | 11 | 882 | 9.3 | 1.3 |

| Expected under hypothesis of equal segregation | 662 | 221 | 882 | 25% | ||

| Chi-square = 98.30, Hypothesis rejected, P < 0.005 (Degrees of Freedom = 2) | ||||||

| Averages for GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous plants A–D (n=4) | 9.60 (1.17) | 1.30 (0.74) | ||||

Table 2. Reciprocal crosses with GCS/gcs-1 heterozygotes indicates a defect in male gametogenesis.

The numbers of observed progeny genotypes were tallied from three independent crosses using the indicated male and female parents. The wild-type (WT) male and female were Col-0. The asterisks mark data and corresponding chi-square values showing that the hypothesis of equal segregation for the gcs-1 allele can be rejected when the male parent is GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous (P < 0.005; Degrees of Freedom = 2). Obs., observed; Exp., expected; Het., heterozygotes.

| Female parent | Male parent | Allele genotyped | Obs. Het. | Obs. WT | Total | Exp. Het. | Exp. WT | Chi-square for hypothesis of equal segregation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCS/gcs | WT | gcs-1 | 14 | 9 | 23 | 12 | 12 | 1.08 |

| WT | GCS/gcs | gcs-1 | 2 | 41 | 43 | 21 | 21 | 34.6* |

|

GCS/gcs ugt80B1 ugt80C1 |

WT | gcs-1 | 10 | 11 | 21 | 11 | 11 | 0.09 |

| WT |

GCS/gcs ugt80B1 ugt80C1 |

gcs-1 | 0 | 22 | 22 | 11 | 11 | 22.0* |

| ugt80B1 | 19 | 0 | 19 | 19 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ugt80C1 | 16 | 0 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

To further investigate the poor transmission of the gcs-1 allele from the male gametophyte, experiments were conducted to assess pollen viability and pollen tube germination. Differential staining for viable versus aborted pollen revealed no visible differences between the GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous and wild-type anthers (Fig. 3a, b). Using a protocol for in vitro pollen tube germination, pollen tubes were visible for ~68% of the pollen grains from either the heterozygous or wild-type flowers (Fig. 3c–g). Quantification of pollen tube germination according to morphology showed no apparent differences between the genotypes (Fig. 3g). Therefore the male gametophyte is likely to be affected by the gcs-1 mutation in a downstream step leading up to fertilization.

Figure 3. Pollen phenotypes from GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous versus wild-type plants.

(a–b) Flower buds were fixed in Carnoy’s solution, and anthers were dissected followed by staining for viability. (a) Wild-type (WT) and (b) GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous anthers both exhibit viable pollen as indicated by magenta-red staining. (c–f) Fresh pollen grains were incubated overnight in a liquid germination medium. (c–d) Long pollen tubes were observed in both (c) WT and (d) GCS/gcs-1 samples. (e) For both genotypes, some pollen grains failed to germinate (“no germ.”) while others had short pollen tubes (“short”). (f) Odd-looking (“odd”) pollen tubes were also observed. (g) Quantification of pollen tube data. No significant differences in pollen tube germination were detected between WT and GCS/gcs-1 samples (t-test; P > 0.05). Averages and standard deviations, as indicated by error bars, are shown for two independent trials with three replicates each (n = 100 pollen grains per replicate).

Subcellular defects of gcs-1 mutants

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to examine subcellular features in gcs-1 seedlings in comparison to wild-type (Fig. 4a–h). The morphologies of the Golgi apparatus and trans-Golgi network (TGN) were visibly affected (Fig. 4e, f). Quantification indicated that gcs-1 mutants have significantly fewer cisternae per Golgi stack in comparison to wild-type (Fig. 4i). Overall, the cells appeared to stain less densely, likely due in part to a relative reduction in rough ER in comparison to wild-type. The cell walls typically had a curvy appearance as compared to wild-type. While chloroplasts were observed in sections from wild-type hypocotyls, no chloroplasts were found among similar sections from gcs-1, consistent with our observations that the mutant seedlings are typically pale and fail to develop a green appearance. Other organelles, such as mitochondria, nuclei, and vacuoles appeared relatively normal, and plasmodesmata were visible in cell walls from both mutant and wild-type sections (Fig. 4c, d, h).

Figure 4. Subcellular defects in gcs-1 mutant seedlings and calli.

(a–h, l–o) Transmission electron micrographs (TEM) reveal ultrastructural features of cells from (a–h) seedling and (l–o) callus cells. (a–h) Seven-day-old seedlings were prepared in longitudinal sections for TEM analysis. (a–d) Representative images of wild-type (WT) in comparison to (e–h) gcs-1 mutant. Subcellular details from (a, e) hypocotyl and (b–d, f–h) root tissues. Red arrows indicate normal Golgi apparatus stacks in (a, b) wild-type in comparison to (f, g) fewer cisternae per Golgi stack in gcs-1 mutants. G, Golgi apparatus; CW, cell wall; PD, plasmodesmata; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; M, mitochondrion; V, vacuole; Ve, vesicles. Compared to (c, d) wild-type cells walls, (g, h) gcs-1 cell walls appear abnormally curvy. (i) Quantification of number of cisternae per Golgi stack. Error bars indicate standard deviations, and a significant difference between wild-type and the gcs-1 mutant is marked by an asterisk (Two-tailed t test, P < 0.0001). (j, k) Cells were propagated on callus induction media followed by fixation and staining with Toluidine blue and Basic fuchin. (j) Wild-type cells appear connected from the outer rim of the callus to the interior, while (k) gcs-1 cells appear abnormally discontinuous and fragmented in the center of the callus. (l–o) TEM of callus cells. (l, n) Nuclei in wild-type and mutant. N, nucleoli. (m, o) Yellow arrows indicate nuclear envelope. In (m) wild-type, nuclear membranes appear intact, whereas in (o) gcs-1 mutants, the nuclear envelope appears discontinuous.

Cells from gcs-1 mutant calli, propagated in callus inducing media (Fig. 1e), were also examined by microscopy (Fig. 4j–o). While the cells in the outer layers of the calli appeared similar in gcs-1 and wild-type, cell morphologies in the interior of calli were abnormal in the mutants (Fig. 4j, k). The cells near the center of the calli appeared smaller and seemed to have lost cell wall adhesion to neighboring cells. TEM of cells corresponding to the periphery revealed differences in the nuclei of the cells. Wild-type cells exhibited nuclear envelopes with double membranes (Fig. 4l, m), whereas in gcs-1 mutants the nuclear envelope appeared to have gaps in the membranes. In addition, the nuclei in gcs-1 mutants appeared pyknotic, and nucleioli were less densely stained (Fig. 4j–o). Reticular forms of mitochondria, indicative of active cell division (Segui-Simarro et al. 2009), were observed in wild-type but not in gcs-1 cells.

Loss of GlcCer biosynthesis is accompanied by alterations in other sphingolipid classes

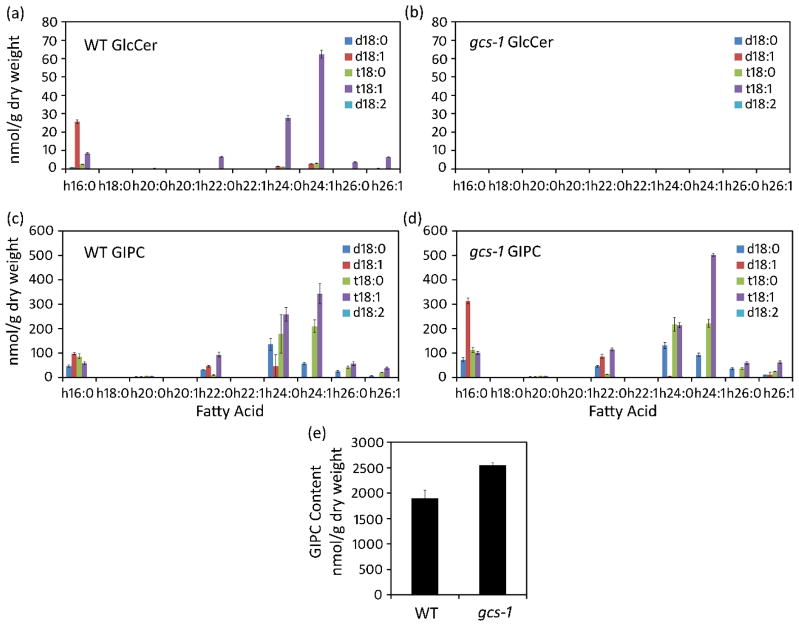

Comprehensive ESI-MS/MS-based profiling was conducted to examine the effect of GCS T-DNA disruption on the complete sphingolipid complement (or “sphingolipidome”) in gcs-1 calli and seedlings. In contrast to the near absence of GlcCer in gcs-1 calli as described above (Fig. 1f, 5a, b), GIPC content was increased in gcs-1 calli relative to wild-type calli (2550 nmol/g DW GIPC in gcs-1 calli versus 1900 nmol/g DW in wild-type calli) (Fig. 5c–e). This increase was due largely to the accumulation of GIPCs with 16:0-OH fatty acid/d18:1 long-chain base ceramide backbones that are typically more enriched in GlcCer. Increases in ceramides and free long-chain bases were also detected in gcs-1 calli compared to wild-type calli (Fig. S4a–f). Sphingolipidome profiles obtained from wild-type and gcs-1 2-week-old seedlings also revealed significant alterations (Fig. S3a–h).

Figure 5. Glucosylceramide (GlcCer) and glycosylinositolphosphoceramide (GIPC) profiles of calli tissues.

Sphingolipid profiles were quantified in nmol/g dry weight. Averages and standard errors, as indicated by error bars, are shown for three independent experiments. GlcCer profiles in wild-type calli (a) and in gcs-1 calli (b). GIPC profiles in wild-type calli (c), and in gcs-1 calli (d). (e) GIPC levels in wild-type and gcs-1 calli.

Homozygous gcs-1 callus displays impaired differentiation and organogenesis that can be chemically rescued

Calli from both gcs-1 and wild-type proliferated on callus-inducing medium containing 0.2 mg/L 2,4-D and 2 mg/L kinetin. Cultures developed similarly with no macroscopic distinctions and both types appeared light green, friable, and unorganized (Fig. 1d, e). Although they were easily propagated, only wild-type calli were able to regenerate roots and shoot-like structures when cultured on differentiation medium without plant growth regulators. Within two weeks, the wild-type calli turned green and differentiated an extensive root system and shoot-like protuberances that continued to grow (Fig. 6a). In contrast, gcs-1 calli never developed roots or shoots, remained yellowish in color (Fig. 6b), and eventually exhibited a necrotic appearance after approximately eight weeks on differentiation medium.

Figure 6. Callus differentiation defects and chemical complementation analysis of gcs-1.

(a) Wild-type (Col-0) callus showing extensive root system and shoot-like protuberances (red arrows) four weeks after transfer to differentiation medium without growth regulators. (b) gcs-1 callus failed to show root or shoot development when transferred to the same medium. (c) Ceramide synthase catalyzes the production of glucosylceramide using glucopsychosine (Glc-LCB) and acyl-CoA (16:0-CoA) as substrates. (d) gcs-1 seedlings cultured for two weeks on MS Phytagel medium developed into a callus-like mass. (e) gcs-1 cultured on medium supplied with 50 μM Glucopsychosine were able to form roots and leaves. (f) Quantification of nhGlcCer in gcs-1 seedlings grown with and without 50 μM Glucopsychosine. (g) Non-hydroxylated GlcCer (nhGlcCer) profiles in gcs-1 seedlings. (h) nhGlcCer profiles in gcs-1 seedlings supplemented with 50 μM Glucopsychosine. Sphingolipid profiles were calculated in nmol/g dry weight. Averages and standard errors, as indicated by error bars, are shown for three independent experiments.

Efforts to chemically rescue the inability of gcs-1 seedlings and calli to differentiate leaves and roots with exogenous GlcCer were not successful, likely due to inefficient uptake of GlcCer. Instead, gcs-1 seedlings were supplied with glucosylated sphingosine, also known as glucopsychosine (d18:1; a non-acylated long chain (sphingoid) bases (LCB) with a glucose head group). Mutant seedlings grown on media supplemented with glucopsychosine displayed shoot growth, and developed leaves as well as a complex root system (Fig. 6e, Fig. S5b). In contrast, gcs-1 mutants without chemical supplementation did not form organs and remained callus-like over the 2-week time course (Fig. 6d, Fig. S5a). gcs-1 mutants supplied with glucopsychosine accumulated only small amounts of the typical GlcCer with hydroxylated fatty acids (0.65 nmol/g DW) (Fig. S6a–c), but non-hydroxylated C16 fatty acids were detected in amounts of nearly 2,000 nmol/g DW, indicating the ability of endogenous enzymes to acylate glucopsychosine to form GlcCer (Fig. 6f–h). Assays of the three Arabidopsis ceramide synthases LOH1, LOH2, and LOH3 revealed that these enzymes are capable of GlcCer production using glucopsychosine and 16:0-CoA as substrates (Fig. 6c). Of these enzymes, LOH2 was most active with these substrates (Fig. S7). These findings indicate that Arabidopsis cells can incorporate glucopsychosine as a substrate for GlcCer production in a process that bypasses the need for an active GCS. Overall, chemical complementation results with glucopsychosine demonstrate the requirement of GlcCer for cell-type differentiation from callus-inducing media.

Arabidopsis is viable with as little as 2% of wild-type GlcCer levels

GCS RNAi suppression lines were generated to define the lower limit of GlcCer content required for normal cell differentiation, organogenesis, and viability of Arabidopsis. For these studies, amiRNA constructs (designated A and B) were generated that targeted two regions of the GCS gene. Transgenic lines showing the greatest GCS suppression from each construct based on qPCR analyses were further characterized (Fig. 7f). Plants from construct A (Line A) displayed developmental abnormalities, including strong reduction in the leaf and petiole sizes relative to wild-type plants (Fig. 7a). These plants lacked lateral root formation and showed shorter hypocotyl length than that of wild-type plants when grown vertically on agar plates in the light and under conditions of etiolation (Fig. 7b–e). Despite these growth phenotypes, Line A plants were fertile and developmental abnormalities were inherited in subsequent generations. Sphingolipid profiling analyses indicated that Line A plants accumulated only ~2% of wild-type GlcCer levels (4 nmol/g DW GlcCer in Line A plants versus 206 nmol/g DW in wild-type plants) (Fig. 7g). This sharp decrease in GlcCer in the RNAi suppression line correlated with increases in GIPC levels (1313 nmol/g dry weight in RNAi Line A versus 453 nmol/g dry weight in wild-type) and slight increases in hydroxyceramides and ceramides (Fig. S8a–h). The line chosen from the B construct transformants showed variability in growth with plants designated as “normal”, “intermediate”, and “small” with regard to size relative to wild-type control plants (Fig. S9a). Small plants, which flowered and generated viable seeds, had ~3% of wild-type GlcCer levels (6 nmol/g DW versus 203 nmol/g DW in wild-type plants). Line B plants designated “normal” had ~25% of wild-type GlcCer levels (Fig. S9b). Taken together, these results show that although GlcCer are essential, plants with as little as ~2 to 3% of wild-type GlcCer levels are viable and maintain vegetative and reproductive growth.

Figure 7. Effects of down-regulation of GCS transcripts.

(a) Comparison with wild-type (Col-0) plants at both vegetative (top) and reproductive (bottom) stages indicate reduced stature in the GCS RNAi line A. Seven-day-old etiolated Col-0 (b) and GCS RNAi line A (c) showed reduced hypocotyl growth in mutant plants relative to wild-type plants. (d) Col-0 and (e) GCS RNAi line A seedlings grown under light for two weeks. (f) Relative expression of GCS transcripts measured in Col-0 and RNAi Line A using Q-RT-PCR. Averages and standard errors are shown for three independent experiments. (g) Glucosylceramide contents (nmol/g dry weight) quantified in Col-0 and RNAi Line A leaves. Averages and standard errors, as indicated by error bars, are shown for three independent experiments.

Discussion

Since GlcCer are major components of the plasma membrane, tonoplast, and the endomembrane system in plants, delineation of their specific roles are critical to unraveling the fundamental mechanisms underlying membrane structure and function. In studies reported here, a GCS null mutant devoid of GlcCer was characterized to more definitively assess the function of this glycosphingolipid in plant cells. Our findings show that despite their abundance in specific membranes, plant cells can proliferate to some extent in the absence of GlcCer, but are defective in their ability to differentiate into specific organs. Moreover, it is remarkable that Arabidopsis GCS RNAi suppression lines with as little as 2% of wild-type levels of GlcCer are fertile, indicating that plants have only a minimal requirement for GlcCer for differentiation, including the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. In addition, it is especially notable that Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which lacks GlcCer, does not normally differentiate from a budding yeast to filamentous state (Dickson et al. 2002). In contrast to S. cerevisiae, filamentous and dimorphic fungi are observed to produce GlcCer (Noble, et al. 2010, Ramamoorthy, et al. 2007). Similar to our observations in Arabidopsis, disruption of GCS function in fungi does not affect basic cell viability but has been noted to reduce fungal hyphal and mycelial growth and can affect virulence of pathogenic fungi (Noble, et al. 2010, Ramamoorthy, et al. 2007, Rittenour et al. 2011, Zhu et al. 2014).

In the present study, seedlings homozygous for T-DNA disruption of GlcCer were observed to be severely reduced in size relative to seedlings genotyped as wild-type or heterozygous for T-DNA insert. These seedlings also failed to form observable root hairs or had little or no ability to form first leaves. Although the gcs-1 mutant seedlings were capable of forming calli that proliferated for up to 8 weeks on sucrose-containing media, these cells did not differentiate into organs, including leaves and roots, when maintained on media with hormone concentrations capable of promoting differentiation of callus from wild-type seedlings. In addition, transmission of the gcs-1 mutant allele through the male gametophyte was also partially impaired. Notably, no significant differences were observed in pollen viability or pollen germination relative to wild-type plants, suggesting that the pollen defect may be due to impaired pollen tube growth toward the egg cell. Alternatively or in addition, the lack of GCS enzyme activity and concomitant decrease in GlcCer may result in defects in nuclear migration, cell-cell fusion and/or nuclear fusion events that are mediated by the male gametophyte prior to fertilization of the egg cell. Consistent with the importance of GlcCer for pollen function, a recent lipidomic study revealed that in Arabidopsis, GlcCer are more enriched in pollen than in leaves, and their composition in pollen is structurally distinct from that in leaves, particularly with regard to the LCB composition of ceramide backbones (Luttgeharm, et al. 2015b).

The microscopy studies were aimed at understanding the cellular basis for the developmental defects of gcs-1 mutants. Golgi apparatus morphologies were visibly affected, and gcs-1 mutants displayed significantly fewer cisternae per Golgi stack in comparison to the wild-type. Consistent with our results, previous reports describing treatment of Arabidopsis roots with the GCS inhibitor PDMP indicated a role for GlcCer in Golgi-mediated trafficking of proteins (Kruger, et al. 2012, Melser, et al. 2010, Melser, et al. 2011). How can the observed defects in protein trafficking hinder developmental functions, but allow basic cell division to occur in a near normal manner in gcs-1 mutants? Perhaps multicellularity and differentiation require a network of proteins that undergo extensive trafficking through the secretory pathway. Moreover, many secreted proteins are likely to be important in cell-signaling events including cell adhesion. Our observation that cell adhesion is disrupted in gcs-1 mutant calli is indicative of disruption of cell-cell communication between neighboring cells. In addition to their critical importance for protein trafficking, it is possible GlcCer act as signaling molecules in triggering or regulating cell-type differentiation.

Our studies also provide information regarding channeling of ceramides between glycosphingolipid classes. Interestingly, gcs-1 calli were not found to accumulate ceramides as might be predicted for loss of GCS activity. Instead, ceramide structures normally enriched in GlcCer, including those with dihydroxy LCBs (e.g., d18:1) and C16 fatty acid, were detected in increased amounts in GIPCs of gcs-1 calli. In addition, total GIPC levels were higher in gcs-1 calli, in amounts proportional to GlcCer amounts found in wild-type calli. This finding suggests that ceramides normally used for GlcCer production are converted to inositolphosphoceramides (IPC) for GIPC synthesis without competition for glucosylation in gcs-1 calli. Further investigation of this phenomenon in gcs-1 cells may provide insights into how certain ceramide structures are normally differentially apportioned between GlcCer and GIPC biosynthesis pathways.

In strong support of our data from the mutants, we showed that the inability of gcs-1 seedlings to differentiate can be chemically rescued by exogenous supply of the psychosine glucosyl sphingosine to media. This compound was readily incorporated into GlcCer via fatty acid acylation, most likely by activities of native ceramide synthases, which we demonstrated can use glucosyl sphingosine as a substrate. In addition, GlcCer levels in chemically-complemented seedlings were >10-fold higher than amounts produced by mutants without psychosine supplementation, suggesting that psychosine-derived GlcCer production bypasses mechanisms or metabolic bottlenecks that normally mediate or limit GlcCer levels in plant cells. Furthermore, the GlcCer produced from psychosine was mostly non-hydroxylated, and nearly devoid of the α- or 2-hydroxy fatty acids normally found in GlcCer in plant cells. This observation indicates that GlcCer are not substrates for fatty acid α-hydroxylation and is consistent with findings of others suggesting that sphingolipid α-hydroxylation uses free ceramides rather than fatty acyl-CoAs as substrates (Konig et al. 2012, Nagano et al. 2012). Of note, PDMP treatment of chemically complemented gcs-1 cells may be useful for determining whether this GCS inhibitor has any non-specific effects on cellular processes. Finally, given the effectiveness of glucopsychosine conversion to GlcCer, it is likely that this system would prove useful for examining whether molecules related to GlcCer, such as galactosylceramides and lactosylceramides, are also able to functionally replace GlcCer in conferring cell-type differentiation by supplementation of gcs-1 seedlings and calli with psychosines containing alternative sugar residues. This method may be more widely applicable to the study of mutants defective in other lipid classes via chemical complementation with appropriate lysolipid precursors.

Taken together, our findings provide a more complete understanding of the contributions of GlcCer as specific glycosphingolipids that are critically required for plant cell function. Despite their abundance in specific membranes, our findings reveal that GlcCer are not essential for basic cell viability and proliferation, but are necessary for processes underlying cell-type differentiation that are critical for multicellularity. Furthermore, our observation that viable plants can be obtained with only 2% of wild-type GlcCer levels and previous reports that GlcCer can be reduced by 50 to 75% without effect on Arabidopsis growth (Chen, et al. 2012, Konig, et al. 2012, Melser, et al. 2011) brings into question why plant cells produce GlcCer in large excess of amounts needed to maintain fertility. These unexpected findings may indicate that GlcCer have quantitative significance for plant performance under non-optimal growth conditions. Alternatively or in addition, GlcCer may have accessory roles in plant cells aside from their functions as structural membrane components. One possibility is that GlcCer also serve as a non-cytotoxic repository for excess ceramide production, similar to the role of ceramide glycosylation that has been proposed for mediation of the pluripotency of breast cancer stem cells (Gupta, et al. 2012). Future studies that address the functions of GlcCer in response to various environmental stresses are now poised to further delineate the dynamic roles of these important glycolipids in plants.

Experimental procedures

Characterization of Arabidopsis GCS/At2g19880 T-DNA insertion mutant

SK-2634 seed stock containing a T-DNA insertion in the GCS/At2g19880 locus was obtained from the Saskatoon Arabidopsis T-DNA mutant collection (Robinson et al. 2009a). Genomic DNA was extracted from plant material, and PCR was used to genotype and identify GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous and gcs-1 homozygous mutants from segregating populations using gene-specific primers in conjunction with T-DNA insertion-specific primers P1, P2, and P3 (Table S1). PCR reactions were performed at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, and then 72 °C for 10 min using Taq Polymerase (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) in a volume of 25 μL, including 2 μL of genomic DNA. For analysis of GCS transcript in T-DNA insertion homozygous mutants, total RNA was isolated from plant tissues using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription of mRNA to cDNA was accomplished using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) after treating 1 μg of total RNA with DNaseI (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). PCR was performed to analyze the expression of GCS and Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4 (EIF4/At3g13920), which was used as a control (primers P4–P7; Table S1).

Genetic complementation of GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous plants

For genetic complementation of SK-2634 heterozygous T-DNA insertion mutants, a 5183 bp fragment of the GCS/At2g19880 coding region was amplified from Arabidopsis (Col-0) genomic DNA using primers P8 and P9 (Table S1) that introduced flanking AscI restriction sites to the amplified fragment. After digestion with AscI, the amplified product was cloned into binary vector pB110 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), which contains a CaMV35S-DsRed selection marker, and then introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 by electroporation. Arabidopsis GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous plants were transformed by the floral dip method (Clough et al. 1998), and primary transformants were selected based on a screening for the DsRed marker with a green LED light and a Red 2 camera filter. Selected heterozygous plants were genotyped in the next three generations using GCS genomic oligonucleotide primers P10 and P11 (Table S1), allowing the identification of gcs-1 complemented plants. FLC/At5g10140 served as a control and was amplified using primers P12 and P13 (Table S1).

Plant materials and crosses

Seeds were sown on soil containing Metro-Mix 380, Vermiculite and Perlite (Hummert International, Saint Louis, MO) in a 7:3:2 (w/w/w) ratio and stratified at 4°C for 3 days to 5 days. Germination and plant growth occurred at 23°C under continuous light. Reciprocal crosses were performed with GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous plants and Col-0 as the wild-type. The ugt80B1/At1g43620 (SALK_103581) and ug80C1/At5g24750 (SALK_080068) insertion mutant alleles (Alonso et al. 2003) were used as control markers. To characterize the gcs-1 seedling phenotypes, seeds from GCS/gcs-1 heterozygous plants were surface sterilized and sowed onto 0.8% plant tissue culture grade agar containing 1x Murashige and Skoog (Murashige et al. 1962), 1% (w/v) sucrose and 0.5% (w/v) MES buffer at pH 5.8. For quantification of germination, seeds were sown onto a square plate with a grid containing five seeds per 26 mm × 26 mm square. Seeds were stratified for 3 days to 5 days at 4°C and transferred to 23°C and continuous light. Progeny from the reciprocal crosses were genotyped by PCR (primers P1–P3 and P14–P19; Table S1).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Seedlings or calli were immersion fixed (2% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.2 to pH 7.4), at room temperature overnight, washed and then prepared as described in (Stirling et al. 1995). Samples were embedded in flat molds and polymerized at 60°C for 24h to 48 h. Thin (gold) and semi-thin sections (purple-green) were cut on a Reichert Ultracut S. Thin sections were absorbed onto 200 mesh copper grids and viewed on a FEI CM100 TEM equipped with AMT digital image capture system. Semi-thin sections were mounted on glass slides, stained with Epoxy Tissue Stain (Toluidine blue and Basic fuchsin) and viewed by light microscopy.

Pollen viability staining

Flower buds were fixed in Carnoy’s solution and stored at 4°C prior to staining for viability. Anthers were dissected on a glass slide using a stereo microscope and stained according to a previously described protocol (Peterson 2010). Anthers were imaged with Nikon 80i microscope and a Nikon DS-5M color camera using DS-L2 software.

In vitro pollen tube germination

The liquid pollen tube germination medium was as in (Fan et al. 2001), except that polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used instead of PEG 4000. Pollen tube germination was performed as in (Markham, et al. 2011), with several modifications. For each genotype, ~50 open flowers were collected in 1.5 mL tubes and allowed to dry at room temperature for ~30 min. Flowers were submerged in 1 mL pollen tube germination medium by vortexing at maximal speed for 2–3 min. Pollen grains were separated from floral tissues by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 min, followed by removal of 700 μL, using the remaining 300 μL to resuspend the pollen grains. The pollen suspension was added to the bottom of a 1-inch diameter glass vial, capped and incubated overnight at 21°C under continuous light. The next day, triplicate samples from each genotype were prepared for light microscopy. Blinded experiments were implemented for quantification of pollen tube germination. A Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope and QImaging Retiga EXi camera with QCapture software were used to image pollen tubes.

Sphingolipid analysis of Arabidopsis plant material

Sphingolipid extraction was performed as described in (Markham, et al. 2007). Plant material or calli used to obtain total sphingolipids were analyzed using a Shimadzu Prominence ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system coupled with a QTRAP4000 mass spectrometer (ABSCIEX), as previously described in (Kimberlin, et al. 2013). Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) atomic mass units (amu) for GlcCer containing non-hydroxy fatty acids were calculated by subtracting 16 amu from the Q1 transition of glucosylceramide MRMs described by (Markham, et al. 2007).

Initiation and maintenance of Arabidopsis wild-type and gcs-1 calli

Wild-type (Col-0) and homozygous gcs-1 seedlings were first grown for 2 weeks on Murashige and Skoog basal medium (Murashige, et al. 1962) supplemented with 25 g/L sucrose. Surface-sterilized explants were used to initiate and maintain callus cultures on Gamborg’s B5 medium (Gamborg et al. 1968) supplemented with 2,4-D (0.2 mg/L), and kinetin (2 mg/L). All cultures were grown in square plates on 50 ml medium containing 2 g/L Phytagel™ (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cultures were kept at 25°C under continuous light (cool white fluorescent), with an intensity of 50 μmol m−2 s−1, and calli were excised every month and sub-cultured on the same medium under the same conditions for maintenance of cultures. Wild-type and gcs-1 calli that were sub-cultured for 2 months, were transferred to plates supplied with Murashige and Skoog basal medium without growth regulators. Calli were retained on this medium for 1 month to allow the development of roots and/or shoot-like structures.

Chemical complementation of gcs-1 mutants with glucopsychosine

Homozygous gcs-1 seedlings were cultured on Murashige and Skoog basal medium (Murashige, et al. 1962) containing 2 g/L Phytagel (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 50 μM glucopsychosine (1-β-D-glucosylsphingosine; Matreya, LLC, Pleasant Gap, PA) dissolved in methanol (5 mM stock), and 0.2% (w/v) tergitol NP-40 solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Microsome isolation and ceramide synthase in vitro assay

Microsomes were prepared either from 4-week-old Arabidopsis transgenic plants that overexpressed the LOH2 ceramide synthase (Luttgeharm, et al. 2015b), or from Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain 6602 (Δlag1/Δlac1 + pRS416-lag1; obtained from Howard Riezman) transformed with LOH1 or LOH3 optimized sequences (Luttgeharm, et al. 2015b) as described in (Luttgeharm et al. 2015a). Microsomal proteins and d18:1 glucopsychosine (Matreya, LLC, Pleasant Gap, PA) and palmitoyl-CoA (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) were used for the ceramide synthase in vitro assay as described in (Luttgeharm, et al. 2015a). Glucosylceramide production was analyzed by mass spectrometry as previously described (Markham, et al. 2007), targeting non-hydroxy glucosylceramides.

Generation of GCS/At2g19880 amRNAi silencing constructs

The DsRed plant selection marker cassette was amplified by PCR from the binary vector pB110 vector (Kimberlin, et al. 2013) (primers P20 and P21; Table S1). The PCR product was cloned as an AfeI fragment into the corresponding site of the destination vector pEarleyGate100 (Earley et al. 2006). This resulted in disruption of the Basta resistance gene of this vector and replacement of the plant selection marker with DsRed coding sequence under control of the cassava mosaic virus promoter. The resulting vector was designated pCD3-724-Red. MicroRNA design conducted using procedures and tools described in the WMD3-Web MicroRNA Designer website (http://wmd3.weigelworld.org/ (Schwab et al. 2006)) to generate two miRNA vectors AtGCSamRNAi-A and AtGCSamRNAi-B targeting different sequences. First, two amiRNA were chosen from the potential list of amiRNA of AtGCS generated by WMD3: 5′-TATATAGGAAGTTGTCTGCAA-3′ (AtGCSamRNAi-A) and 5′-TAGTAAGCATATTGTACCCCC-3′ (AtGCSamRNAi-B). Each sequence was uploaded into the oligo design tool of WMD3 by choosing the RS300 (MIR319A Arabidopsis vector) as the template to generate four oligo sequences (P22–P25 and P26–P29; Table S1), which were then used together with RS300 oligo A and RS300 oligo B primer (P30–P31; Table S1) to engineer the corresponding artificial microRNA into the endogenous miR319a precursor by PCR mutagenesis. The PCR products were introduced by Gateway cloning into PENTR/D-TOPO vector to generate pENT_AtGCSamRNAi-A and pENT_AtGCSamRNAi-B. These vectors were linearized by ApaLI digestion. Following gel purification of the linearized plasmids, a Gateway LR reaction was conducted with the binary vector pCD3-724 to generate the final vector pCD3-724-Red-AtGCSamRNAi-A and pCD3-724-Red-AtGCSamRNAi-B vectors that were used for Arabidopsis transformation by floral infiltration of Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 harboring each of the binary vectors. Transformants were selected by DsRed fluorescence of seeds as described above, and selected transformation events were advanced through subsequent generations to obtain homozygous lines.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR

Seedlings expressing the AtGCSamRNAi-A and -B transgenes were grown vertically for 2 weeks at 25°C, under continuous light, with an intensity of 50 μmol m−2 s−1 on Murashige and Skoog basal medium (Murashige, et al. 1962). RNA extraction was followed by cDNA synthesis using SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Q-RT-PCR was conducted with cDNAs generated from three independent experiments, using the BioRad MyiQ iCycler instrument and relative expression values of GCS were determined using optimized QuantiTect primers for both GCS/At2g19880 and the reference gene PP2AA3/At1g13320 (primers P32 and P33; Table S1), using the QuantiFast SYBR Green Supermix (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. PCR-based genotyping of SK-2634 mutants used to identify GCS/gcs-1 heterozygotes.

Figure S2. PCR-based analysis of GCS mRNA transcripts in wild-type (Col-0) and homozygous gcs-1 mutant plants.

Figure S3. Sphingolipid classes detected in wild-type (Col-0) leaves or bulked gcs-1 mutant seedlings.

Figure S4. Ceramide (Cer) and hydroxyceramide (hCer) profiles analyzed from calli generated from either wild-type or gcs-1 seedlings.

Figure S5. Chemical complementation of homozygous gcs-1 seedlings with 50 μM glucopsychosine.

Figure S6. Glucosylceramide (GlcCer) profiles after chemical complementation.

Figure S7. In vitro assay for glucosylceramide (GlcCer) synthesis.

Figure S8. Sphingolipid profiles analyzed in leaves of wild-type (Col-0) or GCS RNAi knockout mutant Line A.

Figure S9. Effects of down-regulation of GCS mRNA transcripts with RNA interference.

Table S1. Oligonucleotide primers used in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the National Science Foundation (MCB-112206 to K.S.; MCB-1158500 to E.B.C). J.M. was supported in part by Professor Tala Awada and the School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Support was provided to A.M.B by the Johnson Cancer Research Center and the Kansas IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE) (NIH P20GM103418) and to E.S.M by NSF-REU grant DBI-1156571.

References

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, Gadrinab C, Heller C, Jeske A, Koesema E, Meyers CC, Parker H, Prednis L, Ansari Y, Choy N, Deen H, Geralt M, Hazari N, Hom E, Karnes M, Mulholland C, Ndubaku R, Schmidt I, Guzman P, guilar-Henonin L, Schmid M, Weigel D, Carter DE, Marchand T, Risseeuw E, Brogden D, Zeko A, Crosby WL, Berry CC, Ecker JR. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2003;301:653–657. doi: 10.1126/science.1086391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner GH, Sherrier DJ, Weimar T, Michaelson LV, Hawkins ND, Macaskill A, Napier JA, Beale MH, Lilley KS, Dupree P. Analysis of detergent-resistant membranes in Arabidopsis. Evidence for plasma membrane lipid rafts. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:104–116. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.053041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacas JL, Bure C, Furt F, Maalouf JP, Badoc A, Cluzet S, Schmitter JM, Antajan E, Mongrand S. Biochemical survey of the polar head of plant glycosylinositolphosphoceramides unravels broad diversity. Phytochemistry. 2013;96:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Cahoon EB, Saucedo-García M, Plasencia J, Gavilanes-Ruíz M. Plant Sphingolipids: Structure, Synthesis and Function. In: Wada H, Murata N, editors. Lipids in Photosynthesis. Springer; Netherlands: 2010. pp. 77–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Markham JE, Cahoon EB. Sphingolipid delta 8 unsaturation is important for glucosylceramide biosynthesis and low-temperature performance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012;69:769–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson RC, Lester RL. Sphingolipid functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1583:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley KW, Haag JR, Pontes O, Opper K, Juehne T, Song K, Pikaard CS. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 2006;45:616–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan LM, Wang YF, Wang H, Wu WH. In vitro Arabidopsis pollen germination and characterization of the inward potassium currents in Arabidopsis pollen grain protoplasts. J Exp Bot. 2001;52:1603–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamborg OL, Miller RA, Ojima K. Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Experimental Cell Research. 1968;50:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(68)90403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillier C, Cacas JL, Recorbet G, Depretre N, Mounier A, Mongrand S, Simon-Plas F, Wipf D, Dumas-Gaudot E. Direct purification of detergent-insoluble membranes from Medicago truncatula root microsomes: comparison between floatation and sedimentation. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:255. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0255-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Bhinge KN, Hosain SB, Xiong K, Gu X, Shi R, Ho MY, Khoo KH, Li SC, Li YT, Ambudkar SV, Jazwinski SM, Liu YY. Ceramide glycosylation by glucosylceramide synthase selectively maintains the properties of breast cancer stem cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:37195–37205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillig I, Leipelt M, Ott C, Zahringer U, Warnecke D, Heinz E. Formation of glucosylceramide and sterol glucoside by a UDP-glucose-dependent glucosylceramide synthase from cotton expressed in Pichia pastoris. FEBS Letters. 2003;553:365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberlin AN, Majumder S, Han G, Chen M, Cahoon RE, Stone JM, Dunn TM, Cahoon EB. Arabidopsis 56-amino acid serine palmitoyltransferase-interacting proteins stimulate sphingolipid synthesis, are essential, and affect mycotoxin sensitivity. Plant Cell. 2013;25:4627–4639. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.116145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig S, Feussner K, Schwarz M, Kaever A, Iven T, Landesfeind M, Ternes P, Karlovsky P, Lipka V, Feussner I. Arabidopsis mutants of sphingolipid fatty acid alpha-hydroxylases accumulate ceramides and salicylates. New Phytol. 2012;196:1086–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger F, Krebs M, Viotti C, Langhans M, Schumacher K, Robinson DG. PDMP induces rapid changes in vacuole morphology in Arabidopsis root cells. J Exp Bot. 2012;64:529–540. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipelt M, Warnecke D, Zahringer U, Ott C, Muller F, Hube B, Heinz E. Glucosylceramide synthases, a gene family responsible for the biosynthesis of glucosphingolipids in animals, plants, and fungi. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33621–33629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YY, Hill RA, Li YT. Ceramide glycosylation catalyzed by glucosylceramide synthase and cancer drug resistance. Advances in Cancer Research. 2013;117:59–89. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394274-6.00003-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttgeharm KD, Cahoon EB, Markham JE. A mass spectrometry-based method for the assay of ceramide synthase substrate specificity. Analytical Biochemistry. 2015a;478:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttgeharm KD, Kimberlin AN, Cahoon RE, Cerny RL, Napier JA, Markham JE, Cahoon EB. Sphingolipid metabolism is strikingly different between pollen and leaf in Arabidopsis as revealed by compositional and gene expression profiling. Phytochemistry. 2015b;115:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DV, Criss AK, Lehoczky JL, Bui VT. Ceramide glucosylation in bean hypocotyl microsomes: evidence that steryl glucoside serves as glucose donor. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;340:311–316. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DV, Steponkus PL. Plasma membrane lipid alterations associated with cold acclimation of winter rye seedlings (Secale cereale L. cv Puma) Plant Physiol. 1987;83:761–767. doi: 10.1104/pp.83.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham JE, Jaworski JG. Rapid measurement of sphingolipids from Arabidopsis thaliana by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:1304–1314. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham JE, Li J, Cahoon EB, Jaworski JG. Separation and identification of major plant sphingolipid classes from leaves. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22684–22694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham JE, Lynch DV, Napier JA, Dunn TM, Cahoon EB. Plant sphingolipids: function follows form. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013;16:350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham JE, Molino D, Gissot L, Bellec Y, Hematy K, Marion J, Belcram K, Palauqui JC, Satiat-Jeunemaitre B, Faure JD. Sphingolipids containing very-long-chain fatty acids define a secretory pathway for specific polar plasma membrane protein targeting in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23:2362–2378. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.080473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melser S, Batailler B, Peypelut M, Poujol C, Bellec Y, Wattelet-Boyer V, Maneta-Peyret L, Faure JD, Moreau P. Glucosylceramide biosynthesis is involved in Golgi morphology and protein secretion in plant cells. Traffic. 2010;11:479–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melser S, Molino D, Batailler B, Peypelut M, Laloi M, Wattelet-Boyer V, Bellec Y, Faure JD, Moreau P. Links between lipid homeostasis, organelle morphodynamics and protein trafficking in eukaryotic and plant secretory pathways. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30:177–193. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0954-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner MC, Cabot MC. Glucosylceramide in Humans. In: Chalfant C, Del Poeta M, editors. Sphingolipids as Signaling and Regulatory Molecules. Landes Bioscience and Springer Science+Business Media; 2010. pp. 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nagano M, Takahara K, Fujimoto M, Tsutsumi N, Uchimiya H, Kawai-Yamada M. Arabidopsis sphingolipid fatty acid 2-hydroxylases (AtFAH1 and AtFAH2) are functionally differentiated in fatty acid 2-hydroxylation and stress responses. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:1138–1148. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.199547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble SM, French S, Kohn LA, Chen V, Johnson AD. Systematic screens of a Candida albicans homozygous deletion library decouple morphogenetic switching and pathogenicity. Nat Genet. 2010;42:590–598. doi: 10.1038/ng.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R, Slovin JP, Chen C. A simplified method for differential staining of aborted and non-aborted pollen grains. International Journal of Plant Biology. 2010:1. [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthy V, Cahoon EB, Li J, Thokala M, Minto RE, Shah DM. Glucosylceramide synthase is essential for alfalfa defensin-mediated growth inhibition but not for pathogenicity of Fusarium graminearum. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:771–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittenour WR, Chen M, Cahoon EB, Harris SD. Control of glucosylceramide production and morphogenesis by the Bar1 ceramide synthase in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SJ, Parkin IAP. Bridging the gene-to-function knowledge gap through functional genomics. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2009a;513:153–173. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-427-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SJ, Tang LH, Mooney BA, McKay SJ, Clarke WE, Links MG, Karcz S, Regan S, Wu YY, Gruber MY, Cui D, Yu M, Parkin IA. An archived activation tagged population of Arabidopsis thaliana to facilitate forward genetics approaches. BMC Plant Biol. 2009b;9:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudier F, Gissot L, Beaudoin F, Haslam R, Michaelson L, Marion J, Molino D, Lima A, Bach L, Morin H, Tellier F, Palauqui JC, Bellec Y, Renne C, Miquel M, Dacosta M, Vignard J, Rochat C, Markham JE, Moreau P, Napier J, Faure JD. Very-long-chain fatty acids are involved in polar auxin transport and developmental patterning in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:364–375. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.071209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab R, Ossowski S, Riester M, Warthmann N, Weigel D. Highly specific gene silencing by artificial microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1121–1133. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segui-Simarro JM, Staehelin LA. Mitochondrial reticulation in shoot apical meristem cells of Arabidopsis provides a mechanism for homogenization of mtDNA prior to gamete formation. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2009;4:168–171. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.3.7755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Henry AG, Paumier KL, Li L, Mou K, Dunlop J, Berger Z, Hirst WD. Inhibition of glucosylceramide synthase stimulates autophagy flux in neurons. J Neurochem. 2014;129:884–894. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Plas F, Perraki A, Bayer E, Gerbeau-Pissot P, Mongrand S. An update on plant membrane rafts. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2011;14:642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling P, Franke S, Luthje S, Heinz E. Are glucocerebrosides the predominant sphingolipids in plant plasma membranes? Plant Physiol Biochem. 2005;43:1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling JW, Graff PS. Antigen unmasking for immunoelectron microscopy: Labeling is improved by treating with sodium ethoxide or sodium metaperiodate, then heating on retrieval medium. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 1995;43:115–123. doi: 10.1177/43.2.7529784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevissen K, Warnecke DC, Francois IE, Leipelt M, Heinz E, Ott C, Zahringer U, Thomma BP, Ferket KK, Cammue BP. Defensins from insects and plants interact with fungal glucosylceramides. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3900–3905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titapiwatanakun B, Blakeslee JJ, Bandyopadhyay A, Yang H, Mravec J, Sauer M, Cheng Y, Adamec J, Nagashima A, Geisler M, Sakai T, Friml J, Peer WA, Murphy AS. ABCB19/PGP19 stabilises PIN1 in membrane microdomains in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;57:27–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjellstrom H, Hellgren LI, Wieslander A, Sandelius AS. Lipid asymmetry in plant plasma membranes: phosphate deficiency-induced phospholipid replacement is restricted to the cytosolic leaflet. FASEB Journal. 2010;24:1128–1138. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-139410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoek B, Haas R, Wrage K, Linscheid M, Heinz E. Lipids and enzymatic activities in vacuolar membranes isolated via protoplasts from oat primary leaves. Z Naturforsch. 1983;38c:770–777. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Richter GL, Wang X, Mlodzinska E, Carraro N, Ma G, Jenness M, Chao DY, Peer WA, Murphy AS. Sterols and sphingolipids differentially function in trafficking of the Arabidopsis ABCB19 auxin transporter. Plant J. 2013;74:37–47. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Wang M, Wang W, Ruan R, Ma H, Mao C, Li H. Glucosylceramides are required for mycelial growth and full virulence in Penicillium digitatum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;455:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. PCR-based genotyping of SK-2634 mutants used to identify GCS/gcs-1 heterozygotes.

Figure S2. PCR-based analysis of GCS mRNA transcripts in wild-type (Col-0) and homozygous gcs-1 mutant plants.

Figure S3. Sphingolipid classes detected in wild-type (Col-0) leaves or bulked gcs-1 mutant seedlings.

Figure S4. Ceramide (Cer) and hydroxyceramide (hCer) profiles analyzed from calli generated from either wild-type or gcs-1 seedlings.

Figure S5. Chemical complementation of homozygous gcs-1 seedlings with 50 μM glucopsychosine.

Figure S6. Glucosylceramide (GlcCer) profiles after chemical complementation.

Figure S7. In vitro assay for glucosylceramide (GlcCer) synthesis.

Figure S8. Sphingolipid profiles analyzed in leaves of wild-type (Col-0) or GCS RNAi knockout mutant Line A.

Figure S9. Effects of down-regulation of GCS mRNA transcripts with RNA interference.

Table S1. Oligonucleotide primers used in this paper.