Abstract

Biomedical ontologies play a vital role in healthcare information management, data integration, and decision support. Ontology quality assurance (OQA) is an indispensable part of the ontology engineering cycle. Most existing OQA methods are based on the knowledge provided within the targeted ontology. This paper proposes a novel cross-ontology analysis method, Cross-Ontology Hierarchical Relation Examination (COHeRE), to detect inconsistencies and possible errors in hierarchical relations across multiple ontologies. COHeRE leverages the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) knowledge source and the MapReduce cloud computing technique for systematic, large-scale ontology quality assurance work. COHeRE consists of three main steps with the UMLS concepts and relations as the input. First, the relations claimed in source vocabularies are filtered and aggregated for each pair of concepts. Second, inconsistent relations are detected if a concept pair is related by different types of relations in different source vocabularies. Finally, the uncovered inconsistent relations are voted according to their number of occurrences across different source vocabularies. The voting result together with the inconsistent relations serve as the output of COHeRE for possible ontological change. The highest votes provide initial suggestion on how such inconsistencies might be fixed. In UMLS, 138,987 concept pairs were found to have inconsistent relationships across multiple source vocabularies. 40 inconsistent concept pairs involving hierarchical relationships were randomly selected and manually reviewed by a human expert. 95.8% of the inconsistent relations involved in these concept pairs indeed exist in their source vocabularies rather than being introduced by mistake in the UMLS integration process. 73.7% of the concept pairs with suggested relationship were agreed by the human expert. The effectiveness of COHeRE indicates that UMLS provides a promising environment to enhance qualities of biomedical ontologies by performing cross-ontology examination.

Introduction

An ontology provides a formal description of entities (or concepts) and relationships between entities in a given domain. Ontologies or controlled terminologies in biomedical domains, such as the the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD9CM), play a vital role in healthcare information management. For example, SNOMED CT has been designated in the U.S. and many other countries as the preferred terminology for use of electronic health records (EHRs) [1]. Biomedical ontologies also serve as essential knowledge sources for many biomedical applications including text processing [2, 3], data integration [4, 5], decision support [6], reasoning [7], and information retrieval [8].

Most biomedical ontologies have a large size and a complex structure. It is unavoidable that errors and inconsistencies may be introduced. Hence researchers have proposed auditing methods to detect possible errors and inconsistencies in concepts or relationships to enhance the quality of biomedical ontologies. Jiang and Chute [9] leveraged Formal Concept Analysis to identify missing concepts in SNOMED CT. Zhang and Bodenreider [10, 11] proposed a lattice-based approach for exhaustive auditing of SNOMED CT structure. Gu et al. [12] presented computable methods to detect erroneous relationships in the Foundational Model of Anatomy (FMA). Luo et al. [13] developed an automated method to audit symmetric concepts in FMA using self-bisimilarity and linguistic features of the concept labels. Ochs et al. [14] presented a subject-based abstraction network method to audit SNOMED CT using the relationships provided. Mortensen et al. [15] evaluated crowdsourcing methods to detect errors in SNOMED CT. Zhang et al. [16, 17] developed fast MapReduce algorithms for lattice-based evaluation with dramatically reduced time. We refer to [18] for a more detailed review of early auditing methods for biomedical terminologies.

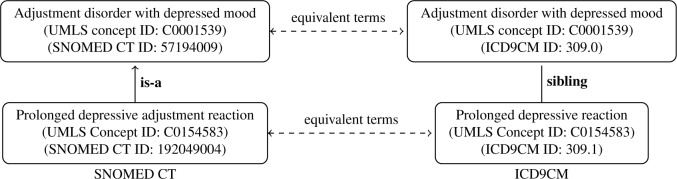

Most existing works have focused on developing auditing methods utilizing the knowledge (e.g., terms, relationships) provided within a targeted ontology. This paper proposes a novel cross-ontology method, Cross-Ontology Hierarchical Relationship Examination (COHeRE), to detect possible errors and inconsistencies in hierarchical relationships across multiple biomedical ontologies in the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) [19]. Inconsistencies uncovered using COHeRE involve UMLS concept pairs related by different types of relationships in disparate source vocabularies. For example, Prolonged depressive adjustment reaction is related to Adjustment disorder with depressed mood through the is-a relationship in SNOMED CT, while Prolonged depressive reaction is related to Adjustment disorder with depressed mood through the sibling relationship in ICD9CM (Figure 1). Since not all such relations can be correct, the inconsistencies provide immediate candidates for auditing and change. For example, the sibling relationship in Figure 1 should probably be changed to is-a, in ICD9CM.

Figure 1:

Example of inconsistent relations in SNOMED CT and ICD9CM integrated in the UMLS.

COHeRE takes the UMLS concepts and relations as input, and produces inconsistent relations (and the number of distinct occurrences) as output. Within UMLS, 138,987 concept pairs were found to have inconsistent relationship types across multiple source vocabularies. 22,644 concept pairs were found to be related by CHD in some source vocabularies, but were specified as other relations (RO) in other vocabularies. 2,755 concept pairs were found to have the hierarchical child relation (CHD) in some source vocabularies, but being in a sibling relation (SIB) in others. Manual evaluation of 40 inconsistent concept pairs detected by COHeRE shows that 95.8% of the involved inconsistent relations indeed exist in their source vocabularies, and 73.7% of the concept pairs with suggested relationship by COHeRE are valid.

1 Background

1.1 Unified Medical Language System (UMLS)

The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) [19], developed by National Library of Medicine (NLM), is a large integrated repository of biomedical source vocabularies to facilitate interoperability among disparate systems in medicine. Knowledge in the UMLS is organized by concept (or meaning). Term variants from source vocabularies are clustered together to form a concept, and each concept is assigned a unique concept identifier (CUI). For example, terms Myocardial infarction, Infarction of heart, Heart attack, MI and Cardiovascular Stroke from different sources represent the same meaning and are assigned a unique CUI: C0027051. The 2014AB release of the UMLS contains over 3 million concepts and 11.9 million unique concept names from more than 150 source vocabularies, including SNOMED CT, FMA, and ICD9CM. The concepts are provided in the distribution file MRCONSO of the UMLS.

Moreover, relationships between terms in source vocabularies are preserved in the UMLS as relationship attributes (RELA). There are over 600 relationship attributes in the UMLS, abstracted into 10 broader relationship types (REL). REL can be further classified as synonymous, hierarchical, or associative. For instance, Coccyx Injury (C0560630) and Back Injury (C0004601) are related through is a (RELA) in SNOMED CT. It is classified as a hierarchical relationship CHD (REL) in the UMLS, where CHD means child relationship. Table 1 shows the UMLS relationships (2014AB release) at different granularity. The 2014AB version of the UMLS contains over 60 million relations between terms, which are provided in the distribution file MRREL. In this paper, relation refers to an individual link between two terms, while relationship indicates a type of relation.

Table 1:

Relationships in the UMLS 2014AB release (REL: relationship, RELA: relationship attribute).

| Class | REL | RELA Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Synonymous | SY (source asserted synonymy) | same as, alias of |

| Hierarchical | CHD (has child relationship in a source vocabulary) | is a, part of |

| PAR (has parent relationship in a source vocabulary) | inverse is a, has part | |

| SIB (has sibling relationship in a source vocabulary) | sibling in is a, sibling in part of | |

| RN (has a narrower relationship) | tradename of, form of | |

| RB (has a broader relationship) | has tradesman, has form | |

| Associative | AQ (Allowed qualifier) | actual outcome of, modifies |

| QB (can be qualified by) | has actual outcome, modified by | |

| RQ (related and possibly synonymous) | classified as, classifies | |

| RO (has relationship other than synonymous, narrower, or broader) | measured by, measures |

1.2 MapReduce

We use a cloud-computing technique called MapReduce [20] in order to process large amounts of data required by COHeRE. MapReduce is a scalable distributed computing framework to process large amounts of data. A MapReduce program consists of a mapper and a reducer, to transform data in the form of key-value pairs. The mapper has a map method to transform input (key, value) pairs into intermediate (key′, value′) pairs. The reducer has a reduce method to transform intermediate (key′, [value′]) aggregates into output (key″, value″) pairs. MapReduce has been successfully used for developing scalable approaches to auditing is a relationship in SNOMED CT [16, 17, 21, 22].

2 Methods

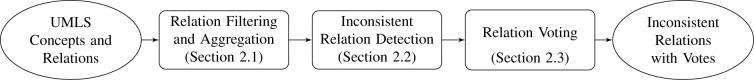

Figure 2 shows the overview of the proposed pipeline of steps for COHeRE. First, the UMLS concepts and relations are taken as the input; relations are filtered according to certain criteria; and relations claimed in source vocabularies are aggregated for each concept pair. Second, inconsistent relations are detected if a concept pair has disparate relations in different source vocabularies. Finally, the inconsistent relations are voted by source vocabularies, and the voting result together with the inconsistent relations are the output.

Figure 2:

Overview of the proposed method COHeRE.

2.1 Relation Filtering and Aggregation

Material preparation. The MRCONSO (1.41GB) and MRREL (5.48GB) distribution files in the UMLS 2014AB release are used as the input for concepts and relations between concepts, respectively. Since UMLS is multilingual and covers a wide range of vocabularies, a subset of most relevant source vocabularies (Table 2) are manually selected to perform the cross-ontology examination for this study. Hence terms that are not in the subset of source vocabularies are discarded from MRCONSO. In addition, concepts with terms containing word unspecified or NOS (Not Otherwise Specified) are filtered out from MRCONSO, since such terms are very likely to cause error-prone relations in the integrated MRREL.

Table 2:

A list of revenant source vocabularies for cross-ontology examination.

| Vocabulary Acronym | Vocabulary Name |

|---|---|

| ATC | Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System |

| CDT | Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature |

| CPM | Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center Medical Entities Dictionary |

| CPT | Current Procedural Terminology |

| FMA | Foundational Model of Anatomy Ontology |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HL7V2.5 | Health Level Seven Vocabulary Version 2.5 |

| HL7V3.0 | Health Level Seven Vocabulary Version 3.0 |

| ICD10 | International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems |

| ICD10CM | International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, Clinical Modification |

| ICD9CM | International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification |

| ICNP | International Classification for Nursing Practice |

| MDR | Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Terminology (MedDRA) |

| MEDCIN | Medicomp Systems |

| MEDLINEPLUS | MedlinePlus Health Topics |

| MSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| MTH | UMLS Metathesaurus |

| NCBI | NCBI Taxonomy |

| NCI | NCI Thesaurus |

| NDFRT | National Drug File - Reference Terminology |

| OMIM | Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man |

| RXNORM | RxNorm Vocabulary |

| SNOMEDCT_US | US Edition of SNOMED CT |

| UMD | Universal Medical Device Nomenclature System |

| VANDF | Veterans Health Administration National Drug File |

Relation filtering

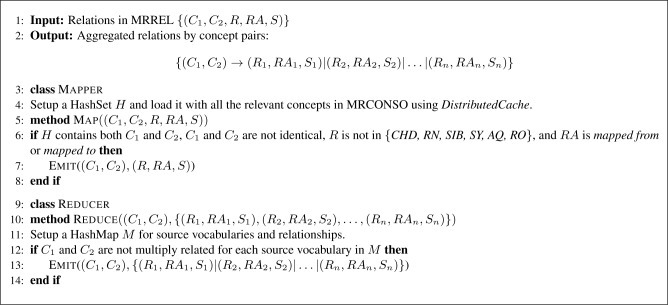

Each relation record in MRREL can be represented as (C1, C2, R, RA, S), where C1 and C2 form a concept pair, R is the relationship between C1 and C2 indicating C2 R C1, RA is the relationship attribute of R, and S is the source vocabulary. Since every source relationship is represented in two directions in separate rows in UMLS, analyzing both directions of a concept pair is redundant. For example, if a concept pair (C1, C2) is related through the CHD relationship with the is a relationship attribute, then (C2, C1) is symmetrically related through the PAR relationship with the inverse is a relation attribute. To avoid duplicated analysis, only one direction CHD is used for analyzing this concept pair. Generally, concept pairs with relationship CHD, RN, SIB, SY, AQ or RO are used for the cross-ontology analysis. In addition, a concept pair is discarded if the concepts share the same unique identifier CUI, since COHeRE will only investigate relationships between distinct concepts. Concept pairs with relationship attribute RA as mapped from or mapped to are also ignored, since they are generated by UMLS and represent mappings between source vocabularies. Due to the large size of the MREEL file, this filtering process is implemented using MapReduce (Mapper in Figure 3) to enable parallel computing.

Figure 3:

MapReduce algorithm for Relation Filtering and Aggregation.

Relation aggregation

For each concept pair (C1, C2), source relationships are aggregated into the format of

Since COHeRE aims to audit ontologies utilizing external knowledge, (C1, C2) are discarded if they are multiply related in a single source vocabulary, that is, there exist i and j such that Ri ≠ Rj but Si = Sj. For example, in the source vocabulary SNOMEDCT_US, concepts Acetaminophen (C0000970) and Acetaminophen 160mg/5mL elixir (C0973757) are related through two relationships: CHD (is a) and RO (has active ingredient). Such inconsistencies are discarded at the single source level. The relation aggregation process is implemented as a MapReduce Reducer in Figure 3.

In sum, concept pair (C1, C2) with relationship R and relationship attribute RA is filtered out if one of the following criteria is met:

the relationship R is not CHD, RN, SIB, SY, AQ or RO;

the two concepts C1 and C2 share the same unique identifier CUI;

the relation attribute RA is mapped from or mapped to;

if the two concepts C1 and C2 are multiply related in a single source vocabulary after relation aggregation.

2.2 Inconsistent Relation Detection

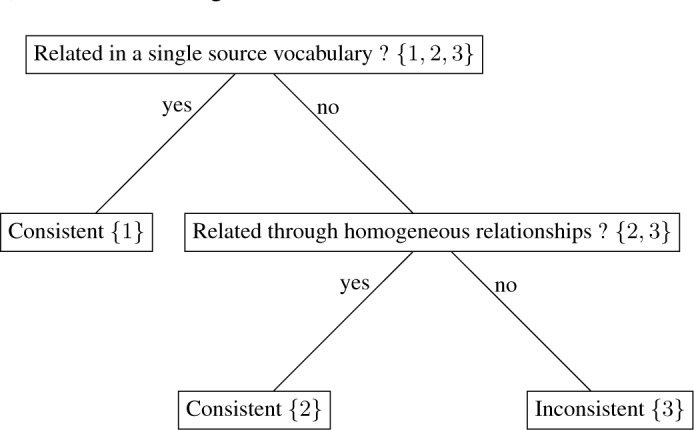

For each pair of concepts obtained in the Relation Filtering and Aggregation step, the concepts are related either in a single source vocabulary or in multiple source vocabularies. For instance, the concepts Arginine supplement (C3853287) and Arginine and glutamine supplement (C3853286) are related through CHD only in a single source vocabulary SNOMEDCT_US (No. 1 in Table 3); the concepts Hexosamines (C0019478) and Fructosamine (C0060765) are related through CHD in both MSH and NDFRT (No. 2 in Table 3); the concepts 17-Oxosteroid (C0000167) and Androstenedione (C0002860) are related through SIB in CPM and CHD in both MSH and NDFRT (No. 3 in Table 3).

Table 3:

Examples of concept pairs after the Relation Filtering and Aggregation process

| No. | Concept pair (C1, C2) | Relationships and source vocabularies {(R, RA, S)} |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Arginine supplement (C3853287), Arginine and glutamine supplement (C3853286) |

CHD, is a, SNOMEDCT_US |

| 2 |

Hexosamines (C0019478) Fructosamine (C0060765) |

CHD, null, MSH | CHD, null, NDFRT |

| 3 |

17-Oxosteroid (C0000167), Androstenedione (C0002860) |

SIB, null, CPM | CHD, null, MSH | CHD, null, NDFRT |

Concepts pairs related in a single vocabulary are considered consistent (see the decision tree in Figure 4). For each concept pair with multiple source vocabularies, the concepts are either related through homogeneous relationships (e.g., No. 2 in Table 3) or non-homogeneous relationships (e.g., No. 3 in Table 3). Concept pairs related through homogeneous relationships are considered consistent, while those related through non-homogeneous relationships are considered inconsistent and collected to facilitate further analysis.

Figure 4:

Decision tree for inconsistent relation detection using the example concept pairs provided in Table 3 as the input. The numbers in the curly brackets indicate the row numbers in Table 3.

2.3 Relation Voting

The inconsistent concept pairs detected above have non-homogeneous relationships across different source vocabularies. A voting module is developed to rank the non-homogeneous relationships by the number of claimed source vocabularies. If the relationship with the most votes has at least 2 votes, then it will serve as a suggestion for correcting potential errors in the inconsistent source vocabularies; otherwise, no suggestion will be made by COHeRE. Take row 3 in Table 3 as an example, the CHD relationship receives 2 votes from the source vocabularies MSH and NDFRT, and the SIB relationship receives 1 vote from the source vocabulary CPM. Hence CHD relationship could be suggested to correct potential error or inconsistency in the source vocabulary CPM. The output of COHeRE are the inconsistent concept pairs and suggested relationships with the most votes.

3 Results

After the Relation Filtering and Aggregation step, 11,921,502 distinct concept pairs were obtained. Among these, 11,372,069 pairs were related in a single source vocabulary, and 549,433 pairs were related in multiple source vocabularies. After the Inconsistent Relation Detection step, 138,987 concept pairs were found with inconsistent relationships across multiple source vocabularies. Table 4 shows the inconsistent relationships containing at least one hierarchical relationship (e.g., CHD or SIB) ranked by the number of concept pairs involved. For example, there were 2,755 concept pairs with inconsistent relationships CHD and SIB, and 1,407 concept pairs with inconsistent relationships CHD and SY. After the Relation Voting step, the concept pairs are classfied according to the number of highest votes. Table 5 shows the numbers of concepts pairs with the highest votes between 1 and 7 with specific examples provided. For instance, there were 962 concept pairs with highest votes at least 3; 51 concepts pairs with highest votes at least 5; and there were no concept pairs with highest votes greater than 6.

Table 4:

Inconsistent relationships with at least one hierarchical relationship (CHD or SIB), ranked by the number of concept pairs involved. Here CHD represents CHD with relationship attribute is a, CHD without relationship attribute specified, or RN with relationship attribute is a; and CHD with other kind of relationship attribute specified is explicitly provided in this table such as CHD (member of). SIB represents SIB with relationship attribute sib in is a or SIB without relationship attribute specified; and SIB with other kind of relationship attribute specified is explicitly provided in this table such as SIB (sib in part of). RO represents RO with any relationship attribute or without relationship attribute specified. RN represents RN with any relationship attribute or without relationship attribute specified. SY represents SY with any relationship attribute or without relationship attribute specified.

| Inconsistent Relationships | No. of Concept Pairs |

|---|---|

| CHD, RO | 22,644 |

| SIB, RO | 24,475 |

| CHD, RN | 6,199 |

| CHD, SIB | 2,755 |

| CHD, SY | 1,407 |

| CHD, RN, RO | 823 |

| CHD, RN, SY | 812 |

| SIB (sib in part of), RO | 797 |

| SIB (sib in part of), SIB | 433 |

| CHD, SIB, RO | 183 |

| CHD, CHD (member of) | 115 |

| SIB (sib in branch of), SIB | 72 |

| CHD, SY, RO | 52 |

| SIB, SY, RO | 46 |

| CHD, SIB (sib in part of) | 35 |

| SIB (sib in branch of), RO | 27 |

| SIB, SY | 25 |

| SIB (sib in tributary of), SIB | 22 |

| SIB (sib in tributary of), RO | 22 |

| CHD, SIB (sib in branch of) | 11 |

| CHD, SIB (sib in tributary of) | 9 |

| CHD, SIB, SY | 8 |

| SIB, RN | 7 |

| CHD (member of), RO | 5 |

| CHD, SIB (sib in part of), RO | 3 |

| CHD, CHD (member of), RO | 3 |

| SIB (sib in part of), RN | 2 |

| SIB (sib in part of), RN, RO | 2 |

| SIB, SIB (sib in part of), RO | 2 |

| CHD, SY, RN, RO | 2 |

| SIB, RN, RO | 2 |

| CHD, SIB, RN | 2 |

| CHD, SIB, SY, RO | 1 |

| SIB, AQ | 1 |

| CHD, SIB, SIB (sib in part of) | 1 |

| CHD, SIB, RN, RO | 1 |

Table 5:

Numbers and examples of concept pairs with top votes at least n (1 ≤ n ≤ 7). n+ means ≥ n.

| No. of Highest Votes | No. of Concept Pairs | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 7+ | 0 | NA |

| 6+ | 2 |

Dengue Fever (C0011311), Severe Dengue (C0019100) 6 votes for CHD: MTH, MSH, NCI, NDFRT, SNOMEDCT_US, MEDCIN 1 vote for SIB: ICD10CM |

| 5+ | 51 |

Methacholine (C0600370), Methacholine Chloride (C0079829) 5 votes for CHD: MTH, MSH, SNOMEDCT_US, MEDCIN, NDFRT 1 vote for RO (has free acid or base form): NCI 1 vote for RN (form of): RXNORM |

| 4+ | 298 |

Thrombocytopenic purpura (C0857305), Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (C0034155) 4 votes for CHD: MSH, NCI, NDFRT, SNOMEDCT_US 1 vote for SIB: MDR |

| 3+ | 962 |

Acetaldehyde (C0000966), Paraldehyde (C0030438) 3 votes for CHD: MTH, MSH, NDFRT 1 vote for SIB: CPM |

| 2+ | 5,937 |

Orthostatic hypotension (C0020651), Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (C1299624) 2 votes for SIB: MSH, MDR 1 vote for CHD: SNOMEDCT_US |

| 1+ | 146,571 | Amylases (C0002712), Isoamylase (C0022143) 1 vote for SIB: MSH 1 vote for CHD: SNOMEDCT_US |

3.1 Evaluation

Since hierarchical relationships are dominant in biomedical ontologies, this study focused on evaluating two types of inconsistent relationships [CHD, RO] and [CHD, SIB] (see Table 4). A random sample of 40 UMLS concept pairs with inconsistent relationships (20 for each type) was selected and manually reviewed by a human expert. Table 6 summarizes the 40 concept pairs into 7 subtypes with examples given. For the [CHD, SIB] type, source vocabularies include MDR, NCI, ICD9CM, ICD10CM, SNOMEDCT_US, GO, FMA, and NDFRT, and the examined 20 pairs of concepts are regarding to disease, syndrome, injury, neoplastic process, cell component, pathologic function, or biologically active substance. For the [CHD, RO (has ingredient)] type, source vocabularies include NDFRT, RXNORM, SNOMEDCT_US, and VANDF, and all the evaluated 12 concept pairs are regarding to clinical drug. For the [CHD, RO (regional part of)] type, source vocabularies include SNOMEDCT_US and FMA, and all the 4 examined concept pairs are regarding to body part or organ component.

Table 6:

Subtypes and examples of the 40 concept pairs with inconsistent relationships examined.

| Subtypes of Inconsistent Relationships | No. | Example |

|---|---|---|

| CHD, SIB | 20 |

Ventricular Dysfunction (C0242973), Right Ventricular Dysfunction (C0242707) CHD: MSH, NCI, NDFRT; SIB: MDR |

| CHD, RO (has ingredient) | 12 |

Buprenorphine/Naloxone (C1169989), Buprenorphine 8 MG/Naloxone 2 MG Sublingual Tablet (C1168831) CHD: SNOMEDCT_US, NDFRT; RO (has ingredient): RXNORM, VANDF |

| CHD, RO (regional part of) | 4 |

Fifth lumbar vertebra (C0223552), Arch of fifth lumbar vertebra (C0223553) CHD: SNOMEDCT_US; RO (regional part of): FMA |

| CHD, RO (has finding site) | 1 |

Ear structure (C0013443), Hyperacusis (C0034880) CHD: OMIM; RO (has finding site): SNOMEDCT_US |

| CHD, RO (negatively regulates) | 1 |

Cell-Matrix Adhesion (C0887869), Negative Regulation of Cell-Matrix Adhesion (C1516324) CHD: NCI; RO (negatively regulates): GO |

| CHD, RO (has manifestation) | 1 |

Dextrocardia (C0011813), Kartagener Syndrome (C0022521) CHD: MSH, SNOMEDCT_US; RO (has manifestation): OMIM |

| CHD, RO (has manifestation), RO (disease may have associated disease) | 1 |

Aniridia (C0003076), WAGR Syndrome (C0206115) CHD: MSH, NDFRT, SNOMEDCT_US; RO (has manifestation): OMIM, RO (disease may have associated disease): NCI |

For each given pair of UMLS concepts, the expert was required to perform the following procedures:

Check if there are terms mapping to them in each source vocabulary involved, and keep records of identifier codes for each term identified in a source vocabulary.

For each relationship between the two concepts, check if the relationship is indeed claimed in the corresponding source vocabulary.

For the relationship with the highest votes as at least 2, choose “agree,” “disagree,” or “not sure” to rate if the expert agrees that it can be used as the correct relationship for the concept pair to resolve inconsistency. For the case that there is 1 vote for each relationship involved, specify one relationship as the correct relationship or answer “not sure.”

Take as an example the UMLS concepts Osteosarcoma metastatic (C0278512) and Extraskeletal osteosarcoma metastatic (C0855050) related through CHD (is a) in NCI and SIB in MDR:

Terms mapping to the concept Osteosarcoma metastatic (C0278512) include C7781 in NCI and 10031246 in MDR. And terms mapping to Extraskeletal osteosarcoma metastatic (C0855050) include C8808 in NCI and 10015849 in MDR.

The relationships CHD (is a) and SIB between the two concepts are indeed claimed in NCI and MDR, respectively.

The expert specifies that CHD (is a) is the correct relationship.

The intention of steps (a) and (b) was to verify if the detected inconsistent relationships for the concept pair indeed exist in the source vocabularies or are caused by the integration process of source vocabularies into the UMLS. They are essential for evaluating COHeRE’s ability to filter out noisy information the integration of UMLS may cause and detect valid inconsistent relationships across different ontologies.

It was verified that all the 40 concept pairs have mapping terms in the involved source vocabularies. For a total of 95 individual relations (note that one concept pair have multiple individual relations in different source vocabularies), only 4 of them were found not claimed in the corresponding source vocabulary. For instance, the is a relation between Metformin (C0025598) and Metformin hydrochloride 1000 MG Oral Tablet (C0978482) was no longer active in SNOMEDCT_US, but still included in the UMLS. In general, 95.8% (91/95) of the individual relations detected by COHeRE is valid.

For cases where the relationship with highest votes is at least 2, there were 19 concept pairs, among which 14 (73.7%) concept pairs were agreed by the expert, 2 disagreed, and 3 not sure. For the case that there is 1 vote for each relationship involved, there were 21 concept pairs, among which, 19 concept pairs were specified a correct relationship by the expert, and 2 not sure.

Manual examination of the verified result indicates the following facts:

ICD9CM, MSH, and MDR sometimes classify concepts related through CHD as SIB. Dermatitis Herpetiformis (C0011608) and Juvenile dermatitis herpetiformis (C0152092) are related through CHD (is a) in SNOMEDCT_US, and SIB in ICD9CM; Neurites (C0085103) and Axon (C0004461) are related through CHD in GO and FMA, and SIB in MSH; Ventricular Dysfunction (C0242973) and Right Ventricular Dysfunctions (C0242707) are related through CHD in MSH, NCI, NDFRT, and SIB in MDR.

SNOMED_CT and NDFRT show inconsistencies regarding to relations between pharmacologic substances and clinical drugs. For instance, the pharmacologic substance Buprenorphine/Naloxone (C1169989) and the clinical drug Buprenorphine 8 MG/Naloxone 2 MG Sublingual Tablet (C1168831) are related through CHD in SNOMED_CT and NDFRT, and RO (has ingredient) in RXNORM and VANDF. However, the pharmacologic substance Potassium Chloride (C0032825) and the clinical drug Potassium Chloride 1 MEQ/ML Oral Solution (C0979640) are indeed related through RO (has active ingredient) in SNOMED_CT, and through RO (has ingredient) in NDFRT. This indicates that SNOMED_US and NDFRT are inconsistent for relating clinical drugs with pharmacologic substances.

SNOMED_CT sometimes relates body parts using CHD (is a) instead of part of. For instance, Fifth lumbar vertebra (C0223552) and Arch of fifth lumbar vertebra (C0223553) are related through CHD in SNOMEDCT_US, and RO (regional part of) in FMA.

4 Discussion

Distinction from related work

COHeRE leverages the knowledge across different ontologies to detect possible errors, which is distinct from most existing OQA works utilizing the knowledge provided within a targeted ontology [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 21]. COHeRE also differs from [22], where the structural disparity between SNOMED CT’s Body Structure sub-hierarchy and FMA was investigated using a cross-ontology method, but the scope was limited to ontological terms relating to human body structure. In [23], Mougin and Grabar exhaustively studied multiply-related concepts within the UMLS, and explored why the multiply-related concepts occur and whether they are inherited from source vocabularies or introduced by the UMLS integration. It was reported that a quarter of multiply-related concepts in UMLS are inherited from source vocabularies [23]. COHeRE differs from [23] in two ways. One is that COHeRE adopts only a subset of source vocabularies that are most relevant for cross-ontology examination. The other is that COHeRE aims to achieve effective filtering mechanism to remove the multiply-related concepts caused by the UMLS integration, and utilize the actual inconsistent relationships across multiple source vocabularies to detect inconsistencies and facilitate ontology quality assurance.

Conceptualization difference analysis

Manual analysis showed conceptual difference between ontologies. Take the concept pair Nipple neoplasm (C1112166) and Benign nipple neoplasm (C1332519) as an example, COHeRE detected two inconsistent relationships: CHD (is a) in the source vocabulary NCI, and SIB in the source vocabulary MDR. In NCI, Nipple neoplasm is classified into Benign nipple neoplasm and Malignant nipple neoplasm. In MDR, “neoplasm” is classified according to “benign,” “malignant,” and “unspecified.” Nipple neoplasm is classified under Breast neoplasms unspecified malignancy, and Benign nipple neoplasm is classified under Breast neoplasms benign. Hence the detected inconsistency is due to the conceptual difference. Although concept terms containing “unspecified” were filtered out by COHeRE, other terms classified under such terms were still included for the inconsistency detection (e.g., Nipple neoplasm under Breast neoplasms unspecified malignancy). To avoid this, the hierarchical information provided by UMLS (the distribution file MRHIER) can be used to remove the descendant terms of those terms containing “unspecified.”

Limitations

First, this study relies on the UMLS knowledge source, and it is not generalizable to domains lacking an integrated ontological system. Second, this study is limited in the number of concept pairs with inconsistent relationships evaluated. Third, this study only focused on evaluating two types of inconsistent relationships ([CHD, SIB] and [CHD, RO]). Evaluating more types of concept pairs may reveal more interesting inconsistencies. Fourth, this study did not investigate concept pairs that are multiply related in a single source vocabulary. It would be interesting to study inconsistent relationships occurring in a single source vocabulary. Lastly, if the ontologies integrated in UMLS are given in the Web Ontology Language (OWL) and the relations are defined as mutually exclusive, then simple OWL inferencing should be able to detect these inconsistencies.

5 Conclusion

This paper presented a novel cross-ontology method, COHeRE, to detect possible errors and inconsistencies in hierarchical relationships across multiple biomedical ontologies. COHeRE leverages the UMLS knowledge source and the MapReduce cloud computing technique for systematic, large-scale ontology quality assurance work. COHeRE is effective in detecting inconsistent hierarchical relations among UMLS source ontologies for quality assurance. The effectiveness of COHeRE indicates that UMLS provides a promising environment to enhance qualities of biomedical ontologies.

References

- [1].Lee D, de Keizer N, Lau F, Cornet R. Literature review of SNOMED CT use. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2014;21(e1):e11–e19. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aronson AR. Effective mapping of biomedical text to the UMLS Metathesaurus: the MetaMap program. AMIA Annual Symp Proc. 2001:17–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cui L, Sahoo SS, Lhatoo SD, Garg G, Rai P, Bozorgi A, Zhang GQ. Complex epilepsy phenotype extraction from narrative clinical discharge summaries. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2014;51:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mate S, Köpcke F, Toddenroth D, et al. Ontology-based data integration between clinical and research systems. PloS one. 2015;10(1):e0116656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang GQ, Cui L, Lhatoo S, Schuele S, Sahoo S. MEDCIS: Multi-Modality Epilepsy Data Capture and Integration System. AMIA Annual Symp Proc. 2014:1248–1257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bodenreider O. Biomedical ontologies in action: role in knowledge management, data integration and decision support. Yearb Med Inform. 2008:67–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Palombi O, Ulliana F, Favier V, Lon JC, Rousset MC. My Corporis Fabrica: an ontology-based tool for reasoning and querying on complex anatomical models. Journal of biomedical semantics. 2014;5:20. doi: 10.1186/2041-1480-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Han Q, Li D, Tan J, Wang X, Fang B, Tian X. MeSH-based Biomedical Information Semantic Retrieval Model. Open Automation and Control Systems Journal. 2014;6:473–479. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jiang G, Chute CG. Auditing the semantic completeness of SNOMED CT using formal concept analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(1):89–102. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang GQ, Bodenreider O. Using SPARQL to Test for Lattices: application to quality assurance in biomedical ontologies. The Semantic Web-ISWC. 2010:273–288. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-17749-1_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang GQ, Bodenreider O. Large-scale, exhaustive lattice-based structural auditing of SNOMED CT. AMIA Annual Symp Proc. 2010:922–926. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gu HH, Wei D, Mejino JL, Elhanan G. Relationship auditing of the FMA ontology. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42(3):550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Luo L, Mejino JLV, Zhang GQ. An Analysis of FMA Using Structural Self-Bisimilarity. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2013;46(3):497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ochs C, Geller J, Perl Y, Chen Y, Xu J, Min H, Case JT, Wei Z. Scalable quality assurance for large SNOMED CT hierarchies using subject-based subtaxonomies. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014 doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-003151. amiajnl–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mortensen JM, Minty EP, Januszyk M, Sweeney TE, Rector AL, Noy NF, Musen MA. Using the wisdom of the crowds to find critical errors in biomedical ontologies: a study of SNOMED CT. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014 Oct 23;:pii. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002901. amiajnl-2014-002901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhang GQ, Zhu W, Sun M, Tao S, Bodenreider O, Cui L. MaPLE: A MapReduce Pipeline for Lattice-based Evaluation and Its Application to SNOMED CT. IEEE International Conference on Big Data 2014 (IEEE BigData 2014) :754–759. doi: 10.1109/BigData.2014.7004301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cui L, Tao S, Zhang GQ. Biomedical Ontology Quality Assurance Using a Big Data Approach. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data; [In press] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhu X, Fan JW, Baorto DM, Weng C, Cimino JJ. A review of auditing methods applied to the content of controlled biomedical terminologies. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42(3):413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bodenreider O. The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS): integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D267–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dean J, Ghemawat S. MapReduce: Simplified data processing on large clusters. Communications of the ACM. 2008;51(1):107–13. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tao S, Cui L, Zhu W, Sun M, Bodenreider O, Zhang GQ. Mining Relation Reversals in the Evolution of SNOMED CT Using MapReduce. AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science. 2015:46–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhu W, Zhang GQ, Tao S, Sun M, Cui L. NEO: Systematic Non-Lattice Embedding of Ontologies for Comparing the Subsumption Relationship in SNOMED CT and in FMA Using MapReduce. AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science. 2015:216–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mougin F, Grabar N. Auditing the multiply-related concepts within the UMLS. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014 Oct;21(e2):e185–93. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]