Abstract

Homeopathy research has focused on chronic conditions; however, the extent to which current homeopathic care is compliant with the Chronic Care Model (CCM) has been sparsely shown. As the Bengali Patient-Assessed Chronic Illness Care (PACIC)-20 was not available, the English questionnaire was translated and evaluated in a government homeopathic hospital in West Bengal, India. The translation was done in six steps, and approved by an expert committee. Face validity was tested by 15 people for comprehension. Test/retest reliability (reproducibility) was tested on 30 patients with chronic conditions. Internal consistency was tested in 377 patients suffering from various chronic conditions. The questionnaire showed acceptable test/retest reliability [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) 0.57–0.75; positive to strong positive correlations; p < 0.0001] for all domains and the total score, strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.86 overall and 0.65–0.82 for individual subscales), and large responsiveness (1.11). The overall mean score percentage seemed to be moderate at 69.5 ± 8.8%. Gender and presence of chronic conditions did not seem to vary significantly with PACIC-20 subscale scores (p > 0.05); however, monthly household income had a significant influence (p < 0.05) on the subscales except for “delivery system or practice design.” Overall, chronic illness care appeared to be quite promising and CCM-compliant. The psychometric properties of the Bengali PACIC-20 were satisfactory, rendering it a valid and reliable instrument for assessing chronic illness care among the patients attending a homeopathic hospital.

Keywords: chronic care model, chronic illness care, disease management, homeopathy, India

1. Introduction

Chronic diseases are major causes of death and disability worldwide with rising prevalence. They pose a significant health threat and an increasing challenge to health care systems.1 Despite advances in treatment, patients with chronic diseases do not always receive optimal care.2 Current care is often event-driven, despite evidence that a structured, proactive approach helps reduce the burden of several chronic diseases.3 Because the causes of chronic diseases are complex, treatment should be multifaceted, integrated, and tailored to patient needs.4

Disease management programs (DMPs) aim to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of chronic care delivery by combining patient-related, professionally directed, and organizational interventions.2 DMPs are often based on the Chronic Care Model (CCM). The CCM has achieved widespread acceptance and reflects the core elements of patient-centered care in chronic diseases. The idea is to transition chronic care from acute and reactive to proactive, planned, and population-based.5 A recent literature review reaffirms the notion that redesigning care using the CCM leads to improved patient care and better health outcomes.6 The model provides an organized multidisciplinary approach to care for patients with chronic diseases. Glasgow and colleagues developed the Patient-Assessed Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) to assess patients’ perspectives of the alignment of primary care to the CCM measurement of care that is patient-centered, proactive, planned, and includes collaborative goal setting, problem solving, and follow-up support.7 Since then, PACIC has emerged as a practical, patient self-report, quality-improvement tool to help organizations evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of their delivery of care for chronic illness and identify areas for improvement, and to evaluate the level and nature of improvements made in their system. It has been used both nationally and internationally as an instrument to evaluate the delivery of CCM activities for a variety of chronic health conditions including, diabetes, osteoarthritis, depression, asthma, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A short version called PACIC-11 (or PACIC-s) and a longer version called PACIC-26 for diabetics were also available.8, 9 Very recently, Dutch versions of PACIC-20 and PACIC-11 have also been developed.4 The paradigm for high-quality chronic illness care now seeks to promote a fuller understanding of the patient’s preferences in order to improve self-management abilities and to activate and/or empower patients.10

Homeopathy research in humans has focused on various chronic conditions; however, no data are available to date showing the extent to which current homeopathic care in any homeopathic setting is CCM-compliant. Until recently, a considerable amount of homeopathic research has concentrated on patient satisfaction,11 development of homeopathic prescribing and patient care indicators,12 patient activation,13 and patient-centered care.14 The authors intended to translate and validate the Bengali version of the PACIC-20 questionnaire and thereafter evaluate the quality of homeopathic chronic illness care in a government homeopathic hospital in West Bengal, India, namely Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homeopathic Medical College and Hospital (MBHMC&H).

2. Methods

Ethics clearance was obtained from the institutional ethics committee prior to conducting the study. All participants were provided with patient information sheets in local vernacular Bengali and informed consents were obtained. The survey matter and questions were also explained verbally to the participants by the research assistant to facilitate easy understanding. No identifiable patient information was required, ensuring anonymity and protection of patient privacy. Also the questionnaires that were filled in by the research assistants were concealed by putting them inside opaque envelops, which were sealed at the survey site. These were sent for data extraction in a specially designed Microsoft Excel master chart that was subjected to statistical analysis in different statistical computational websites.

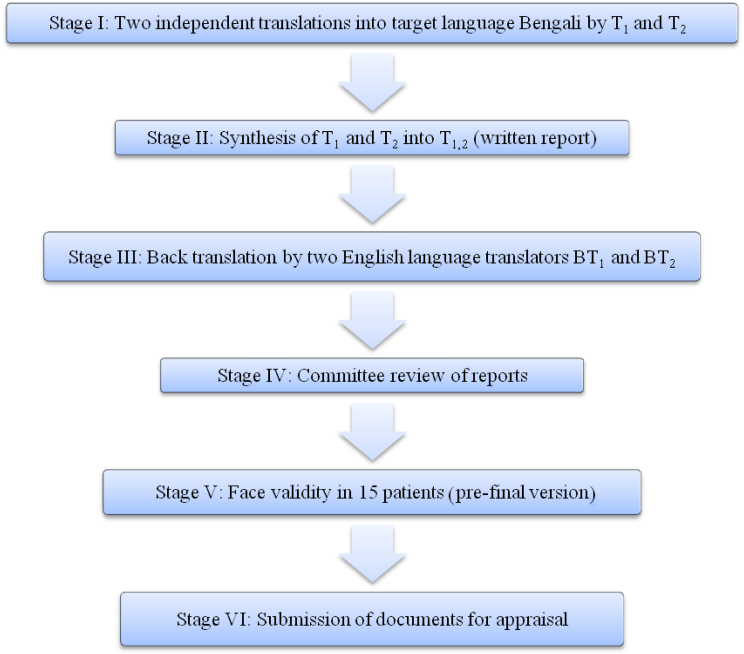

The six different stages that were needed for the development of the study questionnaire are seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation sequence of the Bengali Patient-Assessed Chronic Illness Care (PACIC-20) questionnaire that was used in the study.

2.1. Stage I (forward translation)

For the forward translation from English into Bengali, two independent native Bengali speaking translators translated the English version of PACIC-20 into the target language Bengali (T1 and T2). One of the translators was a clinician and therefore aware of the concepts that were being measured with the PACIC-20 and the other translator was a language specialist with no medical background.

2.2. Stage II (synthesis of T1 and T2 into T1,2)

The two translators had to then agree on one new consensus version of the translation (T1,2). This consensus version was overseen by the expert committee.

2.3. Stage III (back translation)

For the back translation from Bengali into English, two English language translators (BT1 and BT2) were required. Although born in India, they both have been residing in the United States for over 15 years. They both independently translated T1,2 back into English. They were blinded to the original English version of the PACIC-20 during this process.

2.4. Stage IV (expert committee)

The committee consisted of methodologists, health professionals, translators, and a language professional. The committee reviewed all the translations (T1, T2, T1,2, B1, and B2) and the written report comparing the back-translations with the forward translation T1,2. Based on those translations, the pre-final version was developed.

2.5. Stage V (face validity)

The pre-final version of the questionnaire was tested on 15 randomly (simple random sampling) chosen patients visiting outpatient clinics of MBHMC&H. Each completed the questionnaire and was then asked the meaning of each questionnaire item as well as whether or not they had problems with the questionnaire format, layout, content, clarity, language, instructions, or response scales. Any difficulties were noted and included in the final report. A detailed report written by the interviewing person, including proposed changes of the pre-final version based on the results of the face validity test was then submitted to the expert committee.

2.6. Stage VI (committee appraisal)

The final version of the Bengali PACIC-20 was developed by the committee based on the results of the face validity testing and the written report. Thus, all Stages I–VI were successfully completed. The final version of the PACIC-20 for patients is presented in Appendix 1.

2.7. Test/retest reliability

The Bengali PACIC-20 questionnaire was tested for reliability by administering repeatedly to 30 patients at 30-day intervals. The questionnaire item domains were given in different random order for the second administration to avoid the patients memorizing their initial responses.

2.8. Validation

The purpose of cross-cultural adaptation is to try and ensure consistency in the content and face validity between the original and the translated versions of a questionnaire. The content validity of the PACIC-20 questionnaire was previously evaluated in the original English version, and was therefore not tested in this study. Thus in a cross-sectional study in January 2014, 377 patients from different outpatient clinics of MBHMC&H were asked to fill in the new Bengali version of the PACIC-20 provided with a five-point frequency Likert (almost always: 5, almost never: 1). Another section in the questionnaire sought information regarding patients’ gender, age, residence, chronic conditions, self-rated health status, level of education, and monthly family income. The questionnaires were given to them in the practice to fill in immediately. A sample size of 377 was determined taking into account a margin of error of 5%, confidence level of 95%, population size unknown (taken as 20,000), and response distribution estimated to be 50%. A systematic sampling method was used for recruitment of the patients. The sampling fraction was estimated (and approximated) to be 5/6 (n/N; n = required sample size of 377; N = average number of outpatients every day, that is 450); five was decided as the sampling unit by simple random sampling, and thus every 5th patient was interviewed.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using different computation websites. Test/retest reliability of the Bengali PACIC-20 was evaluated by using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with values of ≥ 0.30 considered good. The internal consistency of the Bengali PACIC-20, which measured the degree to which items that made up the total score were all measuring the same underlying attribute, was assessed using Cronbach’s α values with ≥ 0.6 considered acceptable. The sensitivity to change over a time period of 1 month of using the questionnaire was assessed with the standardized response mean (SRM).

Descriptive statistics were presented as absolute values, percentages, means, and standard deviations (SDs). Baseline differences were tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and an independent t test. A p value less than 0.05 for a two-tailed test was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Out of 405 patients approached, 377 (response rate 93.1%) returned the complete questionnaire. The mean total PACIC-20 score percentage seemed to be moderate: 69.5 ± 8.8%. The majority of the respondents were women (n = 201; 53.3%), belonged to the age group 31–45 years (n = 121; 32.1%), had education status of less than high school (n = 239; 63.4%), had a monthly household income of less than 10,000 rupees (n = 329; 87.2%), suffered mostly from rheumatologic complaints (n = 129; 34.2%), with a self-rated health status of poor to fair (n = 175; 46.4%). The other most frequently reported (diagnosed) conditions were piles (n = 22), benign prostatic hypertrophy (n = 12), chronic suppurative otitis media (n = 10), acid peptic disorder (n = 8), urinary tract infection (n = 8), otorrhea (n = 6), COPD (n = 5), diabetes mellitus (n = 4), epilepsy (n = 4), and hypothyroidism (n = 4). Evidently, the conditions were varied and sparse in number, hence they were not tabulated, except the three most frequent—rheumatologic, gynecologic, and allergic (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 377).

| Patient group | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Men | 176 (46.7) |

| Women | 201 (53.3) |

| Age group (y) | |

| 18–30 | 81 (21.5) |

| 31–45 | 121 (32.1) |

| 46–60 | 113 (30.0) |

| > 60 | 62 (16.4) |

| Educational status | |

| Less than high school | 239 (63.4) |

| High school | 99 (26.3) |

| More than high school | 39 (10.3) |

| Monthly income (Indian rupees) | |

| < 10,000 | 329 (87.2) |

| ≥ 10,000 | 48 (12.8) |

| Chronic conditions | |

| Rheumatologic | 129 (34.2) |

| Gynecologic | 73 (19.4) |

| Allergic | 31 (8.2) |

| Othera | 144 (38.2) |

| Health status | |

| Poor to fair | 175 (46.4) |

| Good | 167 (44.3) |

| Very good to excellent | 35 (9.3) |

Frequently reported other conditions included piles, benign prostatic hypertrophy, chronic suppurative otitis media, acid peptic disorder, urinary tract infection, otorrhea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, hypothyroidism, etc.

3.2. Subscale scores and sample characteristics

The “patient activation” subscale score seemed to be influenced significantly by age group (F = 4.337; p = 0.005), education (F = 3.221; p = 0.041), income (t = 4.476; p < 0.0001), and self-rated health status (F = 5.223; p = 0.006). The “delivery system or practice design” subscale score was influenced by education (F = 5.833; p = 0.003) and health status (F = 7.165; p = 0.001). Only monthly income had significant influence on the domains of “goal setting or tailoring” (t = 3.819; p = 0.0003) and “follow-up or coordination” (t = 3.763; p = 0.0004). The “problem solving or contextual” domain scores varied significantly with age groups (F = 3.350; p = 0.019), income (t = −3.763; p = 0.0004), and health status (F = 5.517; p = 0.004) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results for overall PACIC-20 scale and subscales according to patient characteristics (n = 377).

| Patient group | Patient activation | p | Delivery system or practice design | p | Goal setting or tailoring | p | Follow-up or coordination | p | Problem solving or contextual | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender‡ | ||||||||||

| Men | 4.1 (0.7) | 0.167 | 3.5 (0.8) | 0.200 | 3.6 (0.5) | 1.000 | 3.6 (0.6) | 0.136 | 2.8 (0.6) | 1.000 |

| Women | 4.2 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.7) | |||||

| Age groups (y) † | ||||||||||

| 18–30 | 4.2 (0.8) | 0.005∗ | 3.5 (0.8) | 0.303 | 3.7 (0.6) | 0.183 | 3.6 (0.7) | 1.000 | 2.9 (0.7) | 0.019∗ |

| 31–45 | 4.2 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.6) | |||||

| 46–60 | 4.3 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.7) | |||||

| > 60 | 3.9 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.6) | |||||

| Educational status† | ||||||||||

| < High school | 4.2 (0.7) | 0.041∗ | 3.5 (0.7) | 0.003∗ | 3.6 (0.5) | 0.080 | 3.6 (0.7) | 0.682 | 2.7 (0.6) | 0.101 |

| High school | 4.2 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.6) | |||||

| > High school | 3.9 (0.9) | 3.5 (1.1) | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.7) | |||||

| Monthly income‡ | ||||||||||

| ≤ 10,000 | 4.2 (0.6) | < 0.0001∗ | 3.5 (0.7) | 0.265 | 3.6 (0.5) | 0.0003∗ | 3.7 (0.6) | 0.0004∗ | 2.7 (0.6) | 0.0004∗ |

| > 10,000 | 3.6 (0.9) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | |||||

| Chronic conditions† | ||||||||||

| Rheumatologic | 4.2 (0.6) | 0.348 | 3.6 (0.8) | 0.445 | 3.5 (0.5) | 0.434 | 3.6 (0.6) | 0.715 | 2.8 (0.6) | 0.707 |

| Gynecologic | 4.2 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.7) | |||||

| Allergic | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.5) | |||||

| Health status† | ||||||||||

| Poor to fair | 4.1 (0.7) | 0.006∗ | 3.4 (0.8) | 0.001∗ | 3.5 (0.6) | 0.063 | 3.6 (0.7) | 0.339 | 2.7 (0.7) | 0.004∗ |

| Good | 4.3 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.6) | |||||

| Very good–excellent | 4.0 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | |||||

Data are presented as mean (SD).

ANOVA = analysis of variance; PACIC-20 = Patient-Assessed Chronic Illness Care; SD = standard deviation.

Independent t test.

one-way ANOVA.

p less than 0.05 (two-tailed) considered as statistically significant.

3.3. Internal consistency of the Bengali PACIC-20

The Cronbach’s α of the five domains ranged from 0.65 to 0.82, and the overall value was 0.80 indicating acceptable consistency (Table 3).

Table 3.

Item-corrected total correlations and internal consistency of the Bengali PACIC-20 (n = 377).

| Questions and subscales | Pearson’s r (95% CI) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|

| Patient activation | 0.67 (0.61–0.72) | 0.82 |

| Q1 | 0.53 (0.45–0.60) | |

| Q2 | 0.49 (0.41–0.56) | |

| Q3 | 0.58 (0.51–0.64) | |

| Delivery system or practice design | 0.67 (0.61–0.72) | 0.74 |

| Q4 | 0.33 (0.24–0.42) | |

| Q5 | 0.55 (0.48–0.62) | |

| Q6 | 0.56 (0.49–0.63) | |

| Goal setting or tailoring | 0.72 (0.67–0.77) | 0.65 |

| Q7 | 0.46 (0.38–0.54) | |

| Q8 | 0.43 (0.34–0.51) | |

| Q9 | 0.48 (0.40–0.55) | |

| Q10 | 0.07 (−0.03–0.17) | |

| Q11 | 0.41 (0.32–0.49) | |

| Follow-up or coordination | 0.71 (0.66–0.76) | 0.75 |

| Q12 | 0.50 (0.42–0.57) | |

| Q13 | 0.48 (0.40–0.55) | |

| Q14 | 0.51 (0.43–0.58) | |

| Q15 | 0.36 (0.27–0.44) | |

| Problem solving or contextual | 0.63 (0.57–0.69) | 0.71 |

| Q16 | 0.47 (0.39–0.55) | |

| Q17 | 0.44 (0.36–0.52) | |

| Q18 | 0.37 (0.28–0.45) | |

| Q19 | 0.25 (0.15–0.34) | |

| Q20 | 0.21 (0.11–0.30) | |

| All items | 0.80 |

CI = confidence interval; PACIC-20 = Patient-Assessed Chronic Illness Care.

3.4. Test/retest reliability of the Bengali PACIC-20

The ICC values for the Bengali PACIC-20 questionnaire are presented in Table 4. The values (0.57–0.75) reflected strong to very strong positive correlations and significance (p < 0.0001, two-tailed) for all the domains and the total score of the PACIC-20. Only Question 5 showed strong negative correlation—high X variable scores went with low Y variable scores and vice versa. With the exception of Questions 3, 5, 7, and 18, all values were well above the cut-off point of 0.3, which means that all the items contributed significantly to the overall score. The SRM (responsiveness) of the overall questionnaire was very large at 1.11 and that of the five domains ranged from 0.45 to 2.03.

Table 4.

Test/retest reliability of the Bengali PACIC-20 questionnaire (n = 30).

| Questions and subscales | ICC | 95% CI | pǂ | SRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient activation | 0.63 | 0.35–0.81 | < 0.0001* | 0.96 |

| Q1 | 0.69 | 0.44–0.84 | 0.326 | 0.50 |

| Q2 | 0.64 | 0.36–0.81 | < 0.0001* | 0.78 |

| Q3 | 0.21 | −0.16–0.53 | 0.0002 | 0.88 |

| Delivery system or practice design | 0.75 | 0.54–0.87 | 0.029* | 0.45 |

| Q4 | 0.89 | 0.78–0.95 | 0.103 | 0.13 |

| Q5 | −0.88 | −0.43–0.29 | 0.096 | 0.53 |

| Q6 | 0.37 | 0.01–0.64 | 0.032* | 0.42 |

| Goal setting or tailoring | 0.73 | 0.50–0.86 | < 0.0001* | 1.73 |

| Q7 | 0.23 | −0.14–0.55 | < 0.0001* | 1.69 |

| Q8 | 0.77 | 0.57–0.88 | < 0.0001* | 1.20 |

| Q9 | 0.69 | 0.44–0.84 | 0.326 | 0.50 |

| Q10 | 0.53 | 0.21–0.75 | < 0.0001* | 1.09 |

| Q11 | 0.53 | 0.21–0.75 | < 0.0001* | 0.82 |

| Follow-up or coordination | 0.65 | 0.38–0.82 | < 0.0001* | 2.03 |

| Q12 | 0.35 | −0.01–0.63 | < 0.0001* | 1.77 |

| Q13 | 0.61 | 0.32–0.80 | < 0.0001* | 1.31 |

| Q14 | 0.62 | 0.34–0.80 | < 0.0001* | 1.39 |

| Q15 | 0.62 | 0.34–0.80 | < 0.0001* | 0.94 |

| Problem solving or contextual | 0.57 | 0.26–0.77 | < 0.0001 | 2.02 |

| Q16 | 0.91 | 0.82–0.96 | 0.326 | 0.00 |

| Q17 | 0.67 | 0.41–0.83 | < 0.0001* | 1.09 |

| Q18 | 0.16 | −0.21–0.49 | < 0.0001* | 1.48 |

| Q19 | 0.63 | 0.35–0.81 | < 0.0001* | 1.18 |

| Q20 | 0.56 | 0.25–0.77 | < 0.0001* | 1.66 |

| Total score | 0.74 | 0.52–0.87 | < 0.0001 | 1.11 |

*p < 0.05 (two-tailed) considered statistically significant.

CI = confidence interval; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient; PACIC-20 = Patient-Assessed Chronic Illness Care; SRM = standardized response mean or responsiveness.

Paired t test.

4. Discussion

Overall, the Bengali PACIC-20 appeared to be internally consistent, valid, and reliable. Total scores seemed to be moderate in the patients visiting the homeopathic hospital in West Bengal, India. Gender and presence of chronic conditions did not seem to vary significantly with PACIC-20 subscale scores; however, monthly household income had significant influence on the subscales except “delivery system or practice design.”

Our study was limited in the sense that the respondents who were absent on the days of the survey, might have scored differently. Also, our study was restricted to the respondents from a single government homeopathic hospital in West Bengal only, limiting generalizability to another Indian scenario. Also, this cross-sectional survey did not allow causative conclusions. In addition, inevitable incorporation of central tendency bias and acquiescence bias arising from the use of Likert scale responses into the analysis could not be eliminated. Internal consistency might further be improved by rephrasing a few question items having relatively low item-corrected total correlations and low test/retest reliability. Despite these limitations, this study also has several strengths. First, it was the first-ever conducted study that captured information on this context. Second, the respondents in our survey, although limited to a single homeopathic hospital in West Bengal, possessed characteristics similar to others across India. Third, the homeopathic care provided by the homeopathic hospital was similar to the average standard of Indian homeopathic care, and thus our study appears to be generalizable to India. Internal consistency of the questionnaires might further be improved by rephrasing a few question items having an inappropriate level of “nonapplicable” scores and relatively low item-total correlation. Further validation in other Indian samples and more specific statistical (Rasch) analyses will be required to confirm whether the sequence of the original questionnaire will require readjustment to the Indian scenario.

PACIC-20 was only slightly correlated with age, gender, and chronic conditions, and was unrelated to education.7 Our findings were also similar: gender and chronic conditions did not seem to vary significantly with PACIC-20 subscale scores; however, monthly household income had a significant influence on the subscales except for “delivery system or practice design.” Earlier, the PACIC-20 demonstrated moderate test/retest reliability during the course of 3 months,7 but in this study, the correlations seemed to be strong to very strongly positive. The scenario varied significantly with variations in the income status of the patients.

The mean PACIC-20 percentage score derived from our study was higher as compared to other studies. Mean percentage scores of earlier PACIC studies were 53.6 in cardiovascular disease patients4; 64 in diabetes mellitus type 2 patients9; and 54 in diabetes, chronic pain, heart failure, asthma, or coronary artery disease patients.16 The predominance of a different chronic condition (rheumatologic) might have influenced the overall PACIC scores in our study.

The CCM is a widely accepted framework for delivering care to patients with chronic illnesses.7, 15, 16 It focuses on optimization of six key elements of the health care system: health care organization, delivery system design, clinical information systems, decision-support, self-management support, and community resources.16, 17 Adoption of CCM elements by health care providers has been shown to be associated with improved care for patients with chronic illnesses.18 Considering the “quality chasm” between what is known about optimal chronic disease care and what is delivered in practice,19 further implementation and spread of the CCM has the potential for improving quality of care.15 While the PACIC-20 has evolved as a potential tool for quality improvement and for use as a patient-centered quality metric, this potential would be enhanced by demonstrating that PACIC-20 scores are related to other relevant measures of health care quality. This study shall extend the relationship to a wider array of self-management measures across a variety of chronic conditions in homeopathic clinical practice in the hospital setting. Further research is necessary to show if the PACIC-20 can not only be useful as an assessment tool but also as a decision-making tool, showing which elements of chronic care delivery need further improvement, therein leading to improved patient outcomes. Such information will be useful to national quality oversight organizations and other stakeholders interested in identifying “patient-centered” quality of care measures.

Future research should aim at testing the sufficiency of PACIC-20 using indices of model fit by confirmatory factor analysis and testing external longitudinal construct validity through comparisons with similar questionnaires. Other versions of PACIC-20 need to be developed for effective interpretation of the Indian homeopathic care scenario. The authors are currently involved in the development of the translated Bengali short version of PACIC (PACIC-s), PACIC-26 for diabetes, and PACIC for specific clinical conditions like hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, rheumatologic, gynecologic, and allergic conditions, etc.

5. Conclusion

This was the very first step in understanding the status of chronic illness care provided by an Indian homeopathic hospital, which appeared to be quite promising and CCM-compliant. The psychometric properties of the Bengali PACIC-20 also appeared to be satisfactory. Further validation in other Indian samples will be required to confirm whether the sequence of the original questionnaire requires readjustment for Indian populations.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Russell E Glasgow, PhD for giving permission to translate the PACIC-20 into Bengali and use it in our project, and Dr Nikhil Saha, Acting Principal, MBHMC&H for allowing us to carry out the study successfully in his institution. The authors would like to thank Mr Kohinoor Chakraborty, MA and Dr Achintya Kumar Datta, MD for doing the English to Bengali translations as well as Dr Sankar Sengupta, PhD and Mr Indrajit Mitra, MBA for back translations. Additionally, the authors wish to thank Prof. Malay Mundle, MD, Prof. Satadal Das, MD, Dr Mahua Pal, PhD, and Mr Kohinoor Chakraborty, MA for serving on the expert committee and providing input in the final version of the questionnaire. The authors also remain grateful to Mr Arunabha Bhowmick for technical supports and to the patients for their participation in the study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.11.020.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. The Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norris S.L., Glasgow R.E., Engelgau M.M., O'Connor P.J., McCulloch D. Chronic disease management: A definition and systematic approach to component interventions. Dis Manage Health Outcomes. 2003;11:477–488. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenfant C. Shattuck lecture – clinical research to clinical practice – lost in translation? N Engl J Med. 2003;349:868–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cramm J.M., Nieboer A.P. Factorial validation of the patient assessment of chronic illness care (PACIC) and PACIC short version (PACIC-S) among cardiovascular disease patients in the Netherlands. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012;10:104. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCulloch D.K., Price M.J., Hindmarsh M., Wagner E.H. Improvement in diabetes care using an integrated population-based approach in a primary care setting. Dis Manag. 2000;3:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman K., Austin B.T., Brach C., Wagner E.H. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff. 2009;28:75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasgow R.E., Wagner E.H., Schaefer J., Mahoney L.D., Reid R.J., Greene S.M. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) Med Care. 2005;43:436–444. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160375.47920.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gugiu P.C., Coryn C., Clark R., Kuehn A. Development and evaluation of the short version of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care instrument. Chronic Illn. 2009;5:268–276. doi: 10.1177/1742395309348072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glasgow R.E., Nelson C.C., Whitesides H., King D.K. Use of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) with diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2655–2661. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hibbard J.H., Stockard J., Mahoney E.R., Tusler M. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koley M., Saha S., Ghosh S., Mukherjee R., Kundu B., Mondal R. Evaluation of patient satisfaction in a Government Homeopathic Hospital in West Bengal, India. Int J High Dilution Res. 2013;12:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koley M., Saha S., Ghosh S., Nag G., Kundu M., Mondal R. A validation study of homeopathic prescribing and patient care indicators. J Traditional Complement Med. 2014;4(4):289–292. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.133987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saha S., Koley M., Mahoney E.R., Hibbard J., Ghosh S., Nag G. Patient activation measures in a government homeopathic hospital in India. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2014;19:253–259. doi: 10.1177/2156587214540175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saha S., Koley M., Ghosh S., Nag G., Kundu M., Mondal R. A survey on provision of patient-centred care by a government homeopathic hospital in India. Spatula DD. 2014;4:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodenheimer T., Wagner E.H., Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288:1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmittdiel J., Mosen D.M., Glasgow R.E., Hibbard J., Remmers C., Bellows J. Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) and improved patient-centered outcomes for chronic conditions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;23:77–80. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonomi A.E., Wagner E.H., Glasgow R.E., Von Korff M. Assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC): a practical tool to measure quality improvement. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:791–820. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai A.C., Morton S.C., Mangione C.M., Keeler E.B. A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illness. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:478–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGlynn E.A., Asch S.M., Adams J., Keesey J., Hicks J., DeCristofaro A. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.