Abstract

Objectives

Erectile rehabilitation (ER) following radical prostatectomy (RP) is considered an essential component to help men regain erectile functioning; however many men have difficulty adhering to this type of a program. This qualitative study explored men's experience with ER, erectile dysfunction (ED), and ED treatments to inform a psychological intervention designed to help men adhere to ER post-RP.

Methods

Thirty men, one to three years post-RP, who took part in an ER program, participated in one of four focus groups. Thematic analysis was used to identify the primary themes.

Results

Average age was 59 (SD=7); mean time since surgery was 26 months (SD=6). Six primary themes emerged: 1) frustration with the lack of information about post-surgery ED; 2) negative emotional impact of ED and avoidance of sexual situations; 3) negative emotional experience with penile injections and barriers leading to avoidance; 4) the benefit of focusing on the long-term advantage of ER versus short-term anxiety; 5) using humor to help cope; and 6) the benefit of support from partners and peers.

Conclusions

Men's frustration surrounding ED can lead to avoidance of sexual situations and ED treatments, which negatively impact men's adherence to an ER program. The theoretical construct of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) was used to place the themes into a framework to conceptualize the mechanisms underlying both avoidance and adherence in this population. As such, ACT has the potential to serve as a conceptual underpinning of a psychological intervention to help men reduce avoidance to penile injections and adhere to an ER program.

Keywords: prostate cancer, erectile dysfunction, sexual function, erectile rehabilitation

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men, with over 200,000 new cases diagnosed yearly in the US. Because of advances in screening and early detection, 90 percent of men are diagnosed at an early stage (1). One of the “gold standard” treatments for early stage prostate cancer is radical prostatectomy (RP), which has established long-term benefit (2-5). Unfortunately, erectile dysfunction in a common side effect of this procedure. In fact, only 16% of men undergoing a RP will regain their pre-surgery level of erectile functioning (6). Erectile dysfunction (ED) following RP can cause significant distress for the man or couple. The link between ED and depressive symptoms is now well established (7), and the bother associated with ED following RP remains significantly high for at least two years post-surgery (8). For men in committed relationships, this depression and bother can impact the couple, and can result in an avoidance of sexual situations and a loss of intimacy, which in turn can lead to relationship stress and conflict (9-15). For single men, the bother associated with ED can deter the pursuit of romantic relationships (16).

Most surgeries are “nerve sparing” surgeries. This type of surgery spares the cavernous nerves which run bilaterally along the prostate and are responsible for achieving an erection. Despite nerve sparing surgery, the cavernous nerves are stretched and bruised inter-operatively and may take 18 to 24 months post-surgery to heal. Men may fail to have natural erections during this time which can lead to penile tissue atrophy, structural alterations, and venous leak (17). The penile rehabilitation concept promotes the use of erectogenic medications to help men achieve consistent erections, which oxygenates the penile tissue, keeping the tissue healthy. The first-line treatment is oral medications which are PDE5 inhibitors (PDE5i). However, because these medications target the cavernous nerves, only 12 to 17 percent of men will respond to a PDE5i within six months post-surgery (18, 19). An effective second-line treatment is penile injections, which does not require healthy cavernous nerves and is a proven, reliable treatment (20). Thus, penile injections have become the foundation for many RP rehabilitation programs.

Despite the importance of penile rehabilitation following RP, many men find it difficult to sustain the use of erectogenic medication. The majority of men with prostate cancer (50-80%) discontinue the use of medical interventions for ED (i.e., pills, penile injections, vacuum devices) within one year (21, 22). For penile injection therapy, the dropout rates in the first year have ranged from 50 to 80 percent (23-25). In a sample of men with prostate and bladder cancer, only 54 percent continued with injections after four months of starting treatment, and of those, only 45 percent were using the injections at the recommended rehabilitation rate of twice per week (25). This non-compliance may be particularly harmful for men post-RP, since as stated above, the research suggests early and consistent intervention is crucial for erectile rehabilitation (17, 26). Although there is some literature exploring why men stop using injections (e.g., anxiety, cost, pain) (25), little is understood about men's experience of penile rehabilitation, nor is there significant qualitative understanding of the reason for poor compliance and high drop-out, or potential ways to offer assistance to facilitate this process.

Considering erectile function recovery is an important survivorship issue in men with prostate cancer, helping men pursue and consistently use ED treatments has the potential to significantly improve the quality of life for these patients and couples. This qualitative study was focused specifically on men who had used penile injections within the context of penile rehabilitation following RP. Our group has started the development of an intervention based on the concepts of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) to help men utilize ED treatments and consistently adhere to a rehabilitation program. The aim of this qualitative research was to explore men's experience with erectile rehabilitation, ED, and penile injections, and to gain feedback on the proposed intervention.

Methods

Recruitment and Data Collection

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at our institution. A total of 36 men were recruited for four focus groups. Five men did not attend for unknown reasons, and one could not attend due to transportation issues. The remaining 30 participants attended one of the four focus groups.

Eligibility criteria included: men that were one to three years post-RP for early stage prostate cancer, participants in the penile rehabilitation program at our institution using penile injections, and English speaking. The only exception to these criteria included one participant who mentioned during the focus group that he had recently been diagnosed with a rising PSA. Exclusion criteria included: disease recurrence or progression of disease, specific injection phobia, history of bipolar and/or psychotic disorder, or major depression to the extent that would preclude the patient from giving informed consent or being an active participant in the focus group. None of the men met this eligibility criterion for depression. There was no age limit for this study. The main reasons for refusal to participate in the study included: lack of time to participate, scheduling difficulties, lack of interest in participating in research, and geographical barriers. We provided each participant with a monetary incentive of $20 to defray travel expenses. Prior to the focus group, participants completed a demographic form collecting the following information: date of birth, race/ethnicity, marital status, level of education, employment status/occupation, and level of income.

The penile rehabilitation program at our center asks men to achieve penetration hardness erections using penile injections two to three times a week for up to two years post-surgery. We did not designate any eligibility requirement related to men's success adhering to the program as we were interested in a range of men's experiences with rehabilitation (i.e., successful and unsuccessful). We selected a time frame of one to three years post-surgery to allow for a range of experience with the program from, men who were currently active in rehabilitation as well as men who progressed through the two year time frame and could reflect on their experience.

The focus groups were facilitated by an experienced mental health professional using a semi-structured format and lasted approximately an hour and a half. The facilitator asked a standard set of questions in each focus group (with some modifications based on the outcome of each subsequent focus group), and had the ability to ask non-scripted follow-up questions during the discussion. The structured questions centered on their experiences with penile injections, experiences with erectile dysfunction (ED), and thoughts about the upcoming pilot intervention. Silent observers, consisting of three female members of the research staff, observed the focus groups and took notes in an adjacent room behind a one-way mirror. Participants were notified of the observers prior to the start of the focus group. All of the focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed by a third party transcription company.

Data Analysis

Study data consisted of a demographic form and a total of four focus group transcripts. Notes that were taken by observers during the focus groups were used in conjunction with the transcripts and incorporated into the analysis. A targeted procedure of qualitative thematic text analysis was used to analyze the focus group data, including a concentrated review and examination of the transcripts (27-30). The discussion amongst the coders was moderated by an expert in qualitative analysis with more than 10 years of experience in analyzing qualitative data. The analysis team consisted of the study investigators, a qualitative methods specialist, and two research study assistants. The process of analysis was carried out in multiple phases. In Phase One, “margin coding” was utilized. All team members separately read each transcript and highlighted content that was significant or vital to the goals of the research study, including emerging themes and relevant quotes (31). In Phase Two, each analysis team member individually recorded their thoughts about findings/themes which they recognized as important, as well as quotations from the transcript that illuminated the themes. During Phase Three, team members met to share their relevant findings and quotations, and jointly produced a list of themes that emerged from each focus group. Phase Three was repeated until all four focus groups had been analyzed and integrated. In the Fourth Phase, the collective result of the analyzation of all four transcripts was reviewed and the team produced a list of themes which illustrated the most significant findings.

The relevance of the thematic findings identified in Phase Four was assessed in the following ways. Primarily, there was an examination of the conclusions reached by the numerous reviewers and whether analogous conclusions regarding review of the focus group transcripts were attained. When multiple analysts review and synthesize qualitative data - a form of analyst triangulation – it is proposed to heighten the integrity of these results (32, 33). In addition, the extent to which similar themes emerged and repeated across the four transcripts was evaluated and these themes were included in the results (32, 34). Although ACT was used as the underlying structure of the proposed intervention, the ACT framework or ACT themes were not used in the analysis of these data as described above. The majority of coders, including the qualitative expert who facilitated the analysis, had little, if any, prior knowledge of ACT concepts. There was also no a priori plan to organize these themes using an ACT framework as we have done in the Discussion.

Results

Study Sample

The mean time post-RP for the 30 participants was 24.5 (25.9) months (SD = 6.37, Range = 12-36 months). The mean age of the sample was 59 years old (SD = 7), and age ranged from 41 to 72 years. The majority of the sample was Caucasian (83%), married (83%), and were at least college educated (86.6%, Table 1). We did not assess men's success with rehabilitation, however from the transcripts it was clear that men fell on all points of the spectrum of adherence from successful to unsuccessful.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| N | 30 | |

| Mean Age | 59 (SD = 7) years | |

| Mean Time Since Surgery | 26 (SD = 6) months | |

| Race | 80% | White |

| 3.3% | Black/African America | |

| 6.7% | Asian/Pacific Islander | |

| 10% | Unknown | |

| Ethnicity | 10% | Spanish/Hispanic/Latino |

| Marital Status | 83.3% | Married |

| 13.3% | Divorced | |

| 3.3% | Widowed | |

| Education | 53.3% | Graduate Degree |

| 33.3% | College Degree | |

| 10% | Less Than College | |

| Employment Status | 83.3% | Employed Full Time |

| 10% | Retired | |

| 7% | Part-Time or Unemployed | |

Emergent Themes

Six primary themes emerged from these interviews (See Table 2 for representative quotes): 1) frustration with the lack of information about post-surgery ED; 2) negative emotional impact of ED and avoidance of sexual situations; 3) negative emotional experience with penile injections and barriers leading to avoidance; 4) the benefit of focusing on the long-term advantage of rehabilitation versus short-term anxiety; 5) using humor to help cope; and 6) the benefit of support from partners and peers.

Table 2.

Primary Themes and Supporting Quotes

| Frustration with the Lack of Information about Post-surgery ED | “And I think this kind of stuff, I'd much rather have a least—I don't know that I would have done anything different even today, but I'd like to at least know. And, you know, I didn't—I never even thought this kind of thing would—I never even knew oh yeah, you knew about Viagra, but I thought, okay, I got 20 more years before I got to worry about Viagra.” |

| Negative Emotional Impact of ED and the Avoidance of Sexual Situations | “You used the word—and the word that comes around here is anxiety. The real word is fear. I mean fear of losing your male-your maleness.” “It's almost like you're avoiding sex, because you don't—you don't— my wife's kind of avoiding it, so we're kind of doing this dance where you know—I don't want to ask, she doesn't want to ask...” |

| Negative Emotional Experience with Penile Injections and Barriers Leading to Avoidance | “This is the most humiliating thing I've ever done in my life.” “So I think that the whole...business [of penile injections] puts enough of an obstacle in the way that you really almost don't want to try; the least obstacle is the pain of puncturing yourself with a needle.” |

| The Benefit of Focusing on the Long-Term Advantage of Rehabilitation versus Short-Term Anxiety | “Stay healthy, do all the right things long enough until you get back to the life you want.” “But let's be honest, they [partners] want – they want to be – involved and have a sexual life and this made it so that we could have a real sexual life again.” |

| Use of Humor to Help Cope | “So humor clearly helps in terms of adapting, especially if the humor is shared [with your partner].” |

| Support from Partners and Peers | “My friend is amazing. I'm like disgusted by it, and she's like, ‘It's okay. It's no big deal.’ “...Maybe the approach needs to be a little bit different and be a little bit more realistic with men. And perhaps require patients to sit in a room like this— And talk to guys like this who have been through it, so they know what to expect.” |

Frustration with the Lack of Information about Post-surgery ED

The primary theme in all four focus groups was the intense frustration over the lack of information provided to them pre-surgery about erectile dysfunction and potential side-effects following surgery. Although not a topic explicitly queried by the facilitator, it was consistently the first item that men discussed. While most men were aware of some of the sexual dysfunction implications of surgery, they felt the recovery was “over-promised”, and assumed their sexual functioning would return to pre-surgery rates shortly after surgery. As one participant stated, “Critically, it's the information or the lack thereof that makes this such a complicated process.” Several participants questioned the choice of surgery, wondering if they would have selected surgery if they had known the high probability of erectile dysfunction. There was clearly an overwhelming desire to have more information about the side effects of treatment prior to treatment among participants.

Negative Emotional Impact of ED and the Avoidance of Sexual Situations

When asked to talk about their experience with erectile dysfunction, the men expressed a sense of deep disappointment and distress. They reported feelings of “frustration,” “shame,” and “anxiety.” Men characterized the experience as “devastating” and reflected that they did not “feel like a man.” The fundamental shift for men who experience difficulty with erections was described by one participant as, “It's like the ground you walked on since you were a teenager is gone.”

The disappointment and distress related to ED often led to avoidance surrounding sexual situations. The men described that when shame or embarrassment was felt, it resulted in increased anxiety and fear related to sexual situations. When asked specifically what it was like to enter into a sexual situation not feeling confident that they would obtain a firm erection, one man stated, “Fear...its fear, doc, fear,” while another participant remarked that, “It's kind of like you almost don't want to have sex, because you don't want to know that it doesn't work.”

Negative Emotional Experience with Penile Injections and Barriers Leading to Avoidance

As expected, most participants reported initial anxiety and fear when first using injections. However, for many men there was also an enduring negative emotional reaction to penile injections. Many thought of the process as “barbaric” or just “not normal.” One participant said the experience was “brutal” while another man stated that it was “the most humiliating thing I've ever done.” However, it is noteworthy that there was also a distinct group of men (minority of subjects) who reported that once they overcame their initial anxieties or hesitations and adjusted to the process that the injections were “fantastic” and a “life saver.”

The participants also identified several common barriers to consistently using penile injections. Many discussed the “lack of spontaneity” and “unnatural” component of obtaining an erection. Logistical issues such as timing, worry related to achieving the correct injection site, fear of priapism, and storage of the medicine were also concerns. The men reported the pain of the needle stick was minimal and was not a common reason for avoidance of injections. The negative emotional reaction and logistical aspects related to injections were causes of anxiety and barriers that ultimately led to the avoidance of injections.

The Benefit of Focusing on the Long-Term Advantage of Rehabilitation Versus Short-Term Anxiety

A dichotomy emerged between those men who focused on the short-term negative experiences of injection versus men who focused on the longer-term benefits and outcomes of rehabilitation. The long-term focus seemed to help with maintaining treatment over time. Those men with a short-term focus seemed to dwell on the barriers to treatment. Impediments such as pain, loss of spontaneity surrounding sex, logistical issues (e.g., when and where to inject), and emotional distress and shame related to ED were prevalent. Those with long-term focus saw the payoff or reward of injections as worth experiencing some momentary psychological and physical discomfort. As one participant explained, it is important to focus on the overall goal of the rehabilitation process, remain optimistic and keep an “eye on the prize.” Another man proclaimed, “...you know, you gotta use it – you use it or lose it.” Focusing on the long-term goal allowed one man to, “stay healthy, do all the right things long enough until you get back to the life you want.” Those that were focused on the long-term benefit realized that injections were something you must do so that you “don't deteriorate”, to allow for a sex life again, and the opportunity to “feel like a man again.”

Use of Humor to Help Cope

Although not specifically queried, the use of humor to help men cope with ED and the injection process emerged as a clear theme and men frequently joked and laughed throughout the groups. One man remarked, “So humor clearly helps in terms of adapting, especially if the humor is shared [with your partner].” In all of the focus groups, humor pervaded the discussion. For example, in one group there were 75 different moments of laughter (as recorded on the transcription). Laughter and humor were shared during a range of typically distressing topics, including incontinence during long trips, coping with Peyronie's disease, and the experience of dry orgasms.

Support from Partners and Peers

Men discussed that having a supportive partner during this period was helpful in the process. As one man stated, “...respect for your wife has to be very good. I mean she's got to be so faithful and you know, she's got to do – she's got to be there to give you therapy almost.” Having the support of an understanding partner was critical as one participant responded, “That's key. That's key.” Another man stated, “It's almost necessary. And so I thank God every day that she's my wife. And she's fantastic about it.”

Another primary theme was that support from peers is very helpful. Many men stated they did not have anyone to talk to about their experience, or reported that even if they knew someone who had had a RP they had difficulty initiating discussions about their struggles. Many participants remarked how helpful it was to be in the focus groups to hear how other men were coping with using penile injections and normalizing their experience.

Discussion

This qualitative study explored men's experiences with erectile dysfunction and a penile rehabilitation program following radical prostatectomy. Penile rehabilitation programs have demonstrated benefit in helping men recover erectile function following surgery, however many men have difficulty adhering to these rehabilitation programs. These qualitative focus groups were conducted to better understand men's experiences with these programs, and help guide an intervention to help these men sustain a commitment to erectile rehabilitation.

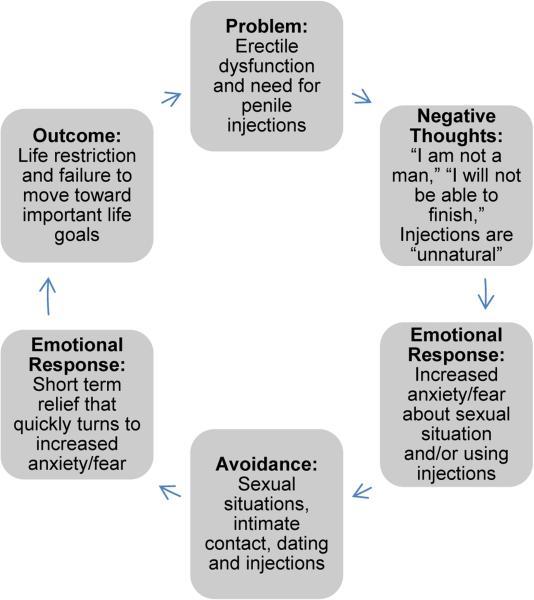

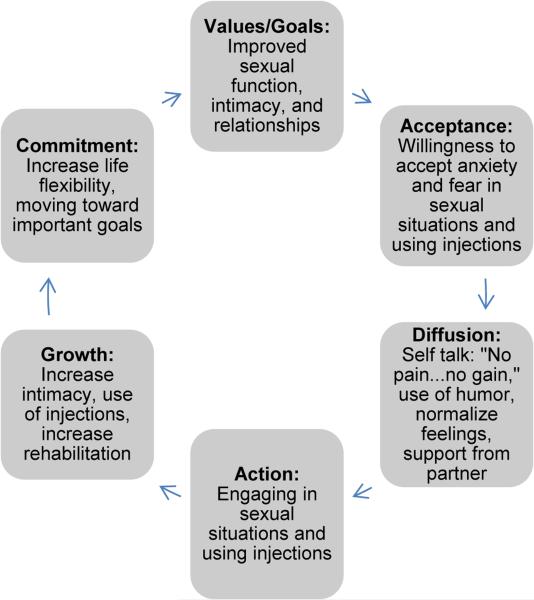

The emotional difficulty that men experience related to ED and ED treatments is well supported in the literature. ED has consistently been associated with depressive symptoms and a reduction of general happiness in life, which has been documented in both quantitative and qualitative reports (7, 10, 16). The unique aspect of this qualitative data is the focus on an erectile rehabilitation program and the discussion of emotional barriers that lead to avoidance of both sexual situations and the use of penile injections. Six primary themes emerged from these interviews: 1) frustration with the lack of information about post-surgery ED; 2) negative emotional impact of ED and avoidance of sexual situations; 3) negative emotional experience with penile injections and barriers leading to avoidance; 4) the benefit of focusing on the long-term advantage of rehabilitation versus short-term anxiety; 5) using humor to help cope; and 6) the benefit of support from partners and peers. We applied an existing psychological framework based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, which describes a theoretical rationale for avoidance (35) to help organize these themes into a coherent framework. Within this framework, a cycle of “control and avoidance” is articulated as well as a cycle of “acceptance and commitment.” Although not all of the emergent themes fit into this ACT framework, the framework may provide a useful way to organize these themes in a way that helps to logically explain the process of avoidance and provides a structure that can be transferred to a clinical intervention (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Cycle of Control and Avoidance

Figure 2.

Cycle of Acceptance and Commitment

Hayes et al. states that the avoidance and control cycle starts with the focus on a problem, which leads to a negative emotional reaction to that problem (36). An effective way to reduce and control these negative emotions is to avoid thinking about or taking any action to resolve the problem. This avoidance leads to a short-term reduction in the negative affect (i.e., relief) but also leads to long-term life restriction and continued struggle with the problem. To apply this cycle to the focus group data, the avoidance of injections seemed to start with the short-term focus on: 1) the problem of erectile function and 2) the need to use penile injections. This focus on the short-term problem facilitated unfavorable thoughts and predictions related to erections and injections. Men in this cycle reported a number of negative cognitions that often predicted failure and subsequent feelings of shame and humiliation. Examples of these negative thoughts related to ED include men thinking they were not a “real man,” that their wife/partner will leave if they cannot “perform,” or the prediction that they will fail and “not be able to finish” sexually. The negative cognitions related to injections included that they are “barbaric”, “brutal,” and “unnatural.” As predicted by the cycle of avoidance and control, the thoughts and predictions then lead to negative emotions and affect. This was evident in the focus groups as some men reported significant fear and anxiety related to entering a sexual situation when they were not confident in their erections, and discussed considerable dread and anxiety related to using penile injections. Thus, for a man in this cycle, considerable negative affect is paired with the thought of approaching a sexual situation or using penile injections. Once this pairing has occurred, avoidance becomes an effective and powerful short-term strategy to reduce the negative affect related to sexual situations and injections. As long as a man does not think about or engage in a sexual situation or use penile injections, he is temporarily shielded from these negative emotions. This avoidance then leads to short-term psychological relief; however this restricts the man from potentially important activities such as engaging in sexual activity or using injections. This is particularly important for men post-RP who are interested in the benefits of an erectile rehabilitation where the lack of consistent erectile activity can significantly decrease the chance of long-term recovery of erections.

The contrast to this cycle of avoidance is the cycle of “acceptance and commitment,” which Hayes et al. states first begins with a focus on important or meaningful goals (36). The next step is an acceptance that achieving important goals is usually accompanied with some form of psychological anxiety. This anxiety can be mitigated or “defused” to some extent; however, it realistically can never be eliminated and at some point there needs to be a willingness to experience this emotional pain while moving toward the goal. This movement toward a goal leads to life flexibility and engagement in important life activities. This success over time can then lead to a reduction in anxiety related to the goal. Men who were successful with using the injections seemed to start with the longer-term goal and focus on the importance/meaning of sexual function, intimacy, and sex in their lives. These men kept their “eye on the prize” and saw the process of rehabilitation as “getting back to the life I want.” These men also accepted that there may be some short-term physical and emotional pain or discomfort. These men noted a willingness to go through the “hassle” of using the injections and possibly enduring some emotional let-down if failures occurred so that they would not “deteriorate” and return to feeling “like a man again.” As part of this successful strategy, men used humor and support to help defuse the negative emotion related to the process. Humor and laughter as a cognitive diffusion permits the person to temporarily withdraw himself from the experience of emotional discomfort, and helps examine emotions or thoughts impartially. It is possible that humor was more successful for men in supportive relationships, as opposed to distressed couples, however all men in these focus group seemed to benefit from the use of humor during the group. Social support was also a valuable resource to help men cope and defuse the emotions related to ED and injections. This support included valuable encouragment from a partner, or the ability to talk with a peer who has experienced the same surgery and rehabilitation process. These processes seemed to start a cycle that ended in the successful use of injections and maintaining a commitment to the rehabilitation process. This allowed men the flexibility to maintain a sex life as an active part of their lives, and preserve this meaningful aspect of who they were as a man. The continued use of injections lead to a reduction in anxiety related to injections and a reduction of negative affect associated with sexual situations. Although men commented that they would clearly prefer not to use the injections, those who reported success also reported that using injections became less difficult over time.

In all, these qualitative interviews provide valuable guidance to the development of a psychological intervention designed to help men use penile injections and adhere to a rehabilitation program. An important element of an intervention may be to help men understand the cycle of avoidance and control, and the cycle of acceptance and commitment related to erectile rehabilitation. Educating men on this framework and coaching them on important concepts, such as focusing on the long-term goal while having the willingness to accept short-term anxiety, may help them adhere to these programs. The ability to organize these themes using an ACT framework suggest ACT concepts may serve as a useful theoretical underpinning for an intervention in this area (35). Elements that may be important to an intervention include: defining the importance of sexuality in the context of their life; education on the side effects and the importance of rehabilitation; acceptance that anxiety will be present during the process; and integration of diffusion techniques such as humor, support, cognitive processing, and normalization.

In addition, it is important to comment on the strongest and most salient theme, which was men's frustration and anger over the lack of proper pre-treatment information about the side effects associated with RP. This is consistent with other qualitative reports which have explored men's experience with prostate cancer treatments (37-40). A majority of the participants were not fully aware of the side effects of RP until they were actually experiencing them, and their frustration with the lack of education was palpable. It is unknown if this lack of education occurred because they are actually not fully informed by their doctors or because they were overwhelmed with information and did not retain all of the facts presented to them. Regardless of the reason, the men clearly believed that more education pre-surgery would help them with their recovery post-surgery. Many believed that if they were more informed, they would have been better prepared practically and emotionally to address these side effects and may have ultimately been more open to or compliant with penile injection treatment. As such, this gives strong justification to start interventions in this area pre-surgery to help men understand the potential impact of surgery and provide the proper education related to the long-term benefits of rehabilitation.

Another important theme discussed was the importance of the partner and the potential benefit of peer support. It seemed that for men in satisfactory relationships, the partner was an important aspect of successfully using injections. This indicates that incorporating the partner, or including information on how men can discuss rehabilitation with their partner, is also an important component to an intervention in this area. It should a be noted that some men in the group reported conflictual relationships where the partner was not supportive. There is a body of clinical literature which highlights that not all partners may be interested in reengaging in a sexual relationship (41). However, good erectile function may be important to a man for a number of reasons, even if sexual relations are infrequent within a couple. Thus, interventions in this area need to have flexibility to coach men on how to engage in a rehabilitation program with supportive and unsupportive partners as well as how to help men without a partner. The potential benefit of peer support also indicates that a peer support component to an intervention may be beneficial.

We believe this study has a number of important strengths: the focus group discussion appropriately addressed men's experience with erectile dysfunction following RP and the use of penile injections; the number of focus groups and attendance at these groups allowed a thorough exploration of the themes resulting in thematic saturation; and the analysis which was moderated by a researcher experienced in qualitative methodology allowed for a robust and productive discussion of the themes.

One methodological weakness of the study may be the use of focus groups as opposed to individual interviews. There may have been some men who felt uncomfortable discussing certain topics in a group format. However, no one expressed this concern during the focus groups and there was no sense from those who observed the focus groups that the men were withholding information or felt uncomfortable discussing these topics in the group setting. In fact, the observers were generally surprised by the candor and honesty of the focus group participants. The high education of the group and lack of racial and ethnic diversity in the sample is another weakness and may limit the generalizability of the findings. It is possible that men with lower education or men from different ethnic groups may think very differently about their experience with rehabilitation. For example, the concept of accepting short-term anxiety for long-term gain may or may not be applicable to men with lower education or those from a different racial background as compared to the sample in this study. Also important to generalizability is the extensive experience our institution has with penile rehabilitation, and men at other institutions may have additional comments related to proper post-surgery education and injection training. Additionally, although the majority of the coders (including the qualitative expert) had little to no knowledge of ACT concepts, the ACT concepts were not mentioned or used in the analysis, nor was there an “a priori” plan to organize the themes using an ACT framework as we have done in the Discussion section, we cannot rule out that our intent to use an ACT framework to guide the development of an intervention may have influenced the analysis of the data.

Conclusion

The analysis of the qualitative data produced six primary themes describing men's frustration with ED and barriers to using penile injections, potentially leading to the avoidance of injections or, conversely, decreased compliance. This avoidance can be particularly damaging to men post-RP attempting to sustain adherence to a penile rehabilitation program. An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) framework can be used to place the themes highlighted in this analysis into a theoretical construct, which outlines both a cycle of avoidance and a cycle of commitment. As such, ACT may serve as an important conceptual underpinning of a psychological intervention to help men reduce avoidance to penile injections and adhere to a penile rehabilitation program following RP. In addition, several participants remarked that participation in the focus group itself was therapeutic, highlighting the importance of increased support, information, and emotional processing for this population.

Acknowledgment of Funding

National Institutes of Health R21 CA 149536

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.ACS. Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M, Haggman M, Andersson SO, Bratell S, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352(19):1977–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eastham JA, Scardino PT, Kattan MW. Predicting an optimal outcome after radical prostatectomy: the trifecta nomogram. The Journal of urology. 2008;179(6):2207–10. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.106. discussion 10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2003;53(1):5–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moul JW. Treatment options for prostate cancer: Part 1 - Stage, grade, PSA, and changes in the 1990s. Am J Manag Care. 1998;4(7):1031–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson CJ, Scardino PT, Eastham JA, Mulhall JP. Back to baseline: erectile function recovery after radical prostatectomy from the patients' perspective. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10(6):1636–43. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Roth AJ. The association between erectile dysfunction and depressive symptoms in men treated for prostate cancer. The journal of sexual medicine. 2011;8(2):560–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson CJ, Deveci S, Stasi J, Scardino PT, Mulhall JP. Sexual bother following radical prostatectomyjsm. The journal of sexual medicine. 2010;7(1 Pt 1):129–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shabsigh R, Klein LT, Seidman S, Kaplan SA, Lehrhoff BJ, Ritter JS. Increased incidence of depressive symptoms in men with erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1998;52(5):848–52. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Araujo AB, Durante R, Feldman HA, Goldstein I, McKinlay JB. The relationship between depressive symptoms and male erectile dysfunction: cross-sectional results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Psychosomatic medicine. 1998;60(4):458–65. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199807000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bokhour BG, Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer: exploring the meanings of “erectile dysfunction”. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):649–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore TM, Strauss JL, Herman S, Donatucci CF. Erectile dysfunction in early, middle, and late adulthood: symptom patterns and psychosocial correlates. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2003;29(5):381–99. doi: 10.1080/00926230390224756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281(6):537–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicolosi A, Moreira ED, Jr., Villa M, Glasser DB. A population study of the association between sexual function, sexual satisfaction and depressive symptoms in men. Journal of affective disorders. 2004;82(2):235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822–30. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomlinson J, Wright D. Impact of erectile dysfunction and its subsequent treatment with sildenafil: qualitative study. Bmj. 2004;328(7447):1037. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38044.662176.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulhall J, Land S, Parker M, Waters WB, Flanigan RC. The use of an erectogenic pharmacotherapy regimen following radical prostatectomy improves recovery of spontaneous erectile function. The journal of sexual medicine. 2005;2(4):532–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00081_1.x. discussion 40-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatzichristou DG. Current treatment and future perspectives for erectile dysfunction. International journal of impotence research. 1998;101(Suppl):S3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabbani F, Stapleton AM, Kattan MW, Wheeler TM, Scardino PT. Factors predicting recovery of erections after radical prostatectomy. The Journal of urology. 2000;164(6):1929–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohler TS, Pedro R, Hendlin K, Utz W, Ugarte R, Reddy P, et al. A pilot study on the early use of the vacuum erection device after radical retropubic prostatectomy. BJU international. 2007;100(4):858–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, Neese L, Klein EA, Zippe C, et al. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95(8):1773–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salonia A, Abdollah F, Gallina A, Pellucchi F, Castillejos Molina RA, Maccagnano C, et al. Does educational status affect a patient's behavior toward erectile dysfunction? The journal of sexual medicine. 2008;5(8):1941–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Althof SE, Turner LA, Levine SB, Risen C, Kursh E, Bodner D, et al. Why do so many people drop out from auto-injection therapy for impotence? Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 1989;15(2):121–9. doi: 10.1080/00926238908403816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss JN, Badlani GH, Ravalli R, Brettschneider N. Reasons for high drop-out rate with self- injection therapy for impotence. International Journal of Impotence Research. 1994;6(3):171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson CJ, Hsiao W, Balk E, Narus J, Tal R, Bennett NE, et al. Injection anxiety and pain in men using intracavernosal injection therapy after radical pelvic surgery. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10(10):2559–65. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montorsi F, Guazzoni G, Strambi LF, Da Pozzo LF, Nava L, Barbieri L, et al. Recovery of spontaneous erectile function after nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy with and without early intracavernous injections of alprostadil: results of a prospective, randomized trial. The Journal of urology. 1997;158(4):1408–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard HR, editor. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quanitative Approaches. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creswell JW, editor. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Sage Publications; Thosand Oaks: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green JT,N, editor. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. Sage Publications; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patton MQ, editor. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miles MBH,AM, editor. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health services research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren CAB, Karner TX. Discovering qualitative methods : field research, interviews, and analysis. xvi. Roxbury Publishing Company; Los Angeles, Calif: 2005. p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren CABK TX. Discovering qualitative methods: Field research, interviews, and analysis. Roxbury Publishing Company; Los Angeles: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy : the process and practice of mindful change. 2nd ed. xiv. Guilford Press; New York: 2012. p. 402. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayes SC. Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life: The New Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. 1st ed New Harbinger Publications; Nov 1, 2005. 2005. p. 224 p. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burt J, Caelli K, Moore K, Anderson M. Radical prostatectomy: men's experiences and postoperative needs. Journal of clinical nursing. 2005;14(7):883–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davison BJ, Gleave ME, Goldenberg SL, Degner LF, Hoffart D, Berkowitz J. Assessing information and decision preferences of men with prostate cancer and their partners. Cancer nursing. 2002;25(1):42–9. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gray RE, Fitch MI, Phillips C, Labrecque M, Klotz L. Presurgery experiences of prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer practice. 1999;7(3):130–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milne JL, Spiers JA, Moore KN. Men's experiences following laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a qualitative descriptive study. International journal of nursing studies. 2008;45(5):765–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.CJ N. The impact of erectile dysfunction of the female partner. Current Sexual Reports. 2006;3:37–41. [Google Scholar]