Abstract

Sexual victimization is prevalent on U.S. college campuses. Some women experience multiple sexual victimizations with heightened risk among those with prior victimization histories. One risk factor for sexual revictimization is alcohol use. Most research has focused on associations between alcohol consumption and revictimization. The current study’s objective was to understand potential mechanisms by which drinking confers risk for revictimization. We hypothesized that specific drinking consequences would predict risk for revictimization above and beyond the quantity of alcohol consumed. There were 162 binge-drinking female students (mean age = 20.21 years, 71.3% White, 36.9% juniors) from the University of Washington who were assessed for baseline victimization (categorized as childhood vs. adolescent victimization), quantity of alcohol consumed, and drinking consequences experienced, then assessed 30 days later for revictimization. There were 40 (24.6%) women who were revictimized in the following 30 days. Results showed that blackout drinking at baseline predicted incapacitated sexual revictimization among women previously victimized as adolescents, after accounting for quantity of alcohol consumed (OR = 1.79, 95% CI [1.07, 3.01]). Other drinking consequences were not strongly predictive of revictimization. Adolescent sexual victimization was an important predictor of sexual revictimization in college women; blackout drinking may confer unique risk for revictimization.

Sexual victimization—attempted or completed sexual assault ranging from unwanted sexual threats or contact to completed rape—is prevalent among women on U. S. college campuses and has received recent national attention (White House Task Force to Protect Students From Sexual Assault, 2014). Among undergraduate women, 19.0% report completed or attempted sexual victimization since entering college (Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher, & Martin, 2007). Importantly, sexual revictimization—the recurrence of sexual victimization—is also common on campuses. Among college-aged women who were raped, 23% were multiple rape victims (Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2000). Revictimization is associated with depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as interpersonal problems such as low assertiveness or intimacy (Classen, Palesh, & Aggarwal, 2005). Thus, these women may constitute a particularly high-risk group requiring intervention to prevent revictimization and its detrimental consequences.

Although multiple studies have highlighted the link between alcohol use and risk for sexual victimization and revictimization in college (e.g., Gidycz et al., 2007), to date, research has focused on the presence or quantity of alcohol consumed by women (e.g., Messman-Moore, Coates, Gaffey, & Johnson, 2008). It remains unclear whether specific alcohol-related factors besides the quantity of alcohol consumed increase risk for victimization. This study examined specific drinking consequences, including impaired control, risky behaviors related to drinking, and blackouts, as possible mechanisms by which alcohol may confer risk for revictimization.

Impaired control (i.e., drinking more or for longer than originally planned) is associated with more frequent and heavier drinking episodes in adolescents (Chung & Martin, 2002), which may lead to greater exposure to situations in which individuals are vulnerable to sexual victimization. Similarly, risky behaviors related to drinking (e.g., having sex with strangers) may increase their exposure to dangerous situations and increase risk for victimization. In a prospective study, alcohol use and expected involvement in risky activities at baseline were associated with revictimization at follow-up (Combs-Lane & Smith, 2002). Blackouts (e.g., not remembering large stretches of time while drinking) may also increase victimization risk, as incapacitated individuals, unaware of their surroundings, may be perceived as more vulnerable by perpetrators, or may be unable to recognize or escape from unsafe situations. For example, 25% of male and 24.6% of female college students who had blacked out later learned they had engaged in some form of sexual activity (White, Jamieson-Drake, & Swartzwelder, 2002).

Additionally, risk for revictimization may differ for women victimized in childhood (e.g., before age 14; Finkelhor, 1979) versus those victimized in adolescence. Two early studies found that adolescent victimization was more strongly related to revictimization in college than child sexual abuse (Gidycz, Coble, Latham, & Layman, 1993; Himelein, 1995). Although childhood sexual abuse predicts revictimization before college (Himelein, 1995; Humphrey & White, 2000), sexual victimization in college may be best predicted by adolescent sexual victimization (e.g., ages 14–18; Humphrey & White, 2000).

The present study examined whether specific drinking consequences experienced by binge-drinking college women and prior victimization history predicted revictimization. We hypothesized that higher levels of impaired control, more alcohol-related risky behaviors, and higher rates of blackout drinking would result in a greater likelihood of revictimization within 30 days following the baseline assessment, above and beyond quantity of alcohol. We hypothesized these would be most predictive for women who had adolescent sexual victimization histories compared to those who experienced child sexual abuse.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were undergraduate women at the University of Washington who participated in a larger study on daily monitoring of posttraumatic stress and alcohol use. There were 11,544 randomly selected women invited; 4,342 completed screening and 860 met study criteria, which included reporting drinking four or more drinks on one occasion at least twice in the past month (i.e., binge drinking criteria; Wechsler et al., 2002) and either (a) no victimization history or (b) history of sexual victimization prior to the past 3 months. A subset of participants (n = 357) was selected for follow-up, including those with (n = 255) and without (n = 102) victimization at baseline. Participants with complete postassessments and victimization at baseline were selected for the current study, resulting in a final sample of N = 162 and a response rate of 64%. In the final sample, t tests and χ2 tests revealed no significant differences between women with victimization at baseline compared to those without regarding age, race, sexual orientation, or class standing. Participants who completed the follow-up assessment and those who did not were not significantly different on drinking quantity or consequences, or victimization status at baseline. Participants reported negative drinking consequences experienced and childhood or adolescent victimization, or both, at baseline, and completed the postassessment for any new sexual victimization that had occurred within the past month. At baseline, study measures were completed online. At follow-up, measures were completed on a computer at the research site. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved this research and informed consent was obtained online.

Measures

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) has good convergent validity (r = .50) with measures of college student drinking (Collins et al., 1985). Participants reported number of drinks consumed on each day of a typical week during the past 3 months, which were summed to produce average quantity consumed per typical week. Drinking consequences in the past 3 months were assessed using the 48-item Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006). The YAACQ has strong concurrent (r = .57 to .85) and test-retest reliability (r = .86; Read, Merrill, Kahler, & Strong, 2007). Internal consistency was good in the current sample for Impaired Control, Risky Behaviors, and Blackout drinking (α = .72 to .79). Physiological dependence was removed from the analyses due to poor internal consistency (α = .36).

Childhood sexual victimization was assessed using the 11-item Childhood Sexual Victimization Questionnaire (CSVQ; Finkelhor, 1979). Events ranged from “kissing and hugging in a sexual way” to having intercourse before the age of 14 with an individual at least 5 years older than the victim. Internal consistency for the current sample was α = .89.

Initial adolescent and young adult (i.e., early 20s) sexual victimization was assessed using an 18-item modified Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss & Gidycz, 1985). Victimization after age 14 was assessed in three domains: (a) attempted or completed oral-genital contact, (b) vaginal or anal intercourse, or (c) penetration of the vagina or anus by other objects. Participants reported if they could not consent because they were under the influence of alcohol or drugs (incapacitated sexual victimization). Internal consistency was α = .76 for the current sample.

Across the CSVQ and SES, participants were coded as sexually victimized if they endorsed one or more incidents of unwanted attempted or completed sexual assault at baseline. Participants were coded as having childhood victimization only if they had no victimization on the SES, adolescent victimization only if they indicated no sexual victimization on the CSVQ, or both childhood and adolescent victimization if they indicated sexual victimization on both the CSVQ and SES. Sexual revictimization in the 30 days since baseline was assessed using two dichotomous (yes/no) variables that were a composite of the questions on the SES: nonalcohol-related sexual victimization and incapacitated sexual victimization.

Data Analysis

Logistic regressions were run with sexual victimization that did not involve alcohol and incapacitated sexual victimization 30 days after baseline as the dependent variables. In each regression, alcohol quantity (drinks per week), drinking consequences, baseline victimization status, and the interaction between drinking consequences and baseline victimization status were entered simultaneously. Nonsignificant interactions were trimmed from the model. A power analysis was calculated. At α = .05 and power (1 – β) = .80, to detect a small effect (odds ratio [OR] = 1.5, 1.8) would require a sample between 304 and 157, respectively. All variables were examined for missing data and rates of missingness were low, ranging from 0 to 7.3%. Listwise deletion was used for logistic regression analyses.

Results

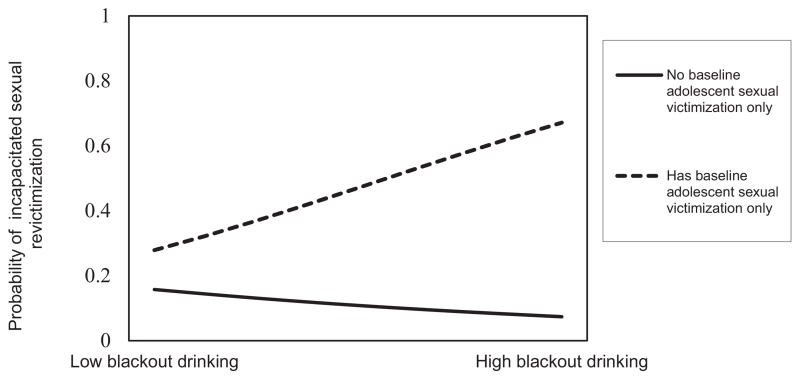

Of the 162 participants, 40 (24.6%) had been revictimized in the 30 days since baseline. Of these, 27 (16.6%) experienced nonalcohol-related sexual victimization, 24 (14.8%) experienced incapacitated sexual victimization, and 11(6.7%) experienced both nonalcohol-related and incapacitated sexual victimization. Table 1 presents bivariate associations between drinking and victimization related variables. Logistic regression analyses revealed none of the drinking consequences reliably predicted nonalcohol-related revictimization 30 days later (OR = [1.01, 1.27], p = .243, .553, .771, respectively). A significant interaction emerged for incapacitated sexual victimization (see Table 2), such that blackout drinking predicted revictimization 30 days later for women with a history of adolescent victimization only (not child sexual victimization), as shown in Figure 1. As indicated in Table 1, there was a strong correlation between adolescent sexual victimization only and both adolescent and child sexual victimization at baseline. To examine the effect of having both types of victimization at baseline on risk for revictimization at follow-up, a separate regression was run for individuals with both childhood and adolescent victimization. Results from this regression (not presented) were consistent with results reported in Table 2, such that those who did not have both childhood and adolescent victimization at baseline were more likely to be revictimized at follow-up. Analyses reported in Table 2 shows that these effects are localized to adolescent victimization.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations of Drinking and Sexual Victimization Variables.

| Variable | n or M | % or SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Drinks per week | 12.32 | 7.94 | — | |||||||

| 2. Impaired control | 2.63 | 1.82 | .28** | — | ||||||

| 3. Risky behaviors | 1.97 | 1.82 | .31** | .42** | — | |||||

| 4. Blackout drinking | 3.35 | 2.16 | .43** | .39** | .47** | — | ||||

| 5. Baseline adolescent sexual victimization | 89 | 54.9 | −.06 | .11 | −.02 | .12 | — | |||

| 6. Baseline child sexual victimization | 12 | 7.4 | −.07 | −.033 | −.18* | −.02 | −.31** | — | ||

| 7. Baseline child, adolescent sexual victimization | 61 | 37.6 | .10 | −.09 | .10 | −.11 | −.86** | −.22** | — | |

| 8. Sexual victimization (nonalcohol) @ 30 days | 27 | 16.6 | .14 | .16 | .17* | .21* | .04 | −.06 | −.01 | — |

| 9. Incapacitated sexual victimization @ 30 days | 24 | 14.8 | .06 | .08 | .11 | .15 | .03 | −.06 | .00 | .36** |

Note. N = 162.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 2. Association of Drinking Consequences and Total Drinks per Week on Incapacitated Sexual Victimization After 30 Days.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Total drinks per week | 1.00 | [0.93, 1.07] |

| Impaired control | 0.96 | [0.72, 1.29] |

| Risky behaviors | 1.14 | [0.84, 1.54] |

| Blackout drinking | 0.82 | [0.52, 1.29] |

| Adolescent sexual victimization at baseline |

1.03 | [0.33, 3.25] |

| Child sexual victimization at baseline |

0.56 | [0.35, 8.71] |

| Blackout Drinking × Adolescent Sexual Victimization |

1.79* | [1.07, 3.01] |

| Blackout Drinking × Child Sexual Victimization |

0.83 | [0.23, 2.97] |

Note. N = 152.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Probability of incapacitated sexual revictimization at high and low levels of blackout drinking for a sample of undergraduate binge-drinking women with and without previous adolescent sexual victimization only at baseline.

Discussion

Blackout drinking at baseline predicted incapacitated sexual revictimization in the following 30 days only for women who had experienced adolescent sexual victimization only at baseline. It did not reliably predict nonalcohol-related revictimization. Other drinking consequences examined did not reliably predict either incapacitated or nonalcohol-related sexual victimization.

Results underscored the need for increased research on the roles of blackout drinking and adolescent victimization history in revictimization. Over half (51%) of undergraduates reported experiencing at least one blackout and women may be more likely to black out than men, even when they drink less because they can reach higher blood alcohol levels (White et al., 2002). Blackout drinking may also deter women from reporting sexual victimization because they are unable to fully recall the event. Consistent with literature suggesting adolescent victimization better predicts college victimization than childhood abuse (Humphrey & White, 2000), blackout drinking predicted incapacitated sexual revictimization only for women first victimized as adolescents or young adults, but not for those victimized as children, the latter of which may represent a more inhibited group. We had relatively few women who reported only child sexual abuse, although proportionally they were less likely to be revictimized than the other groups. More work is needed to determine the specific risk factors associated with adolescent sexual victimization that increase risk for revictimization in college.

Data were collected via retrospective self-report, which may have affected validity because blackout drinking impairs memory. Additionally, as participants reported incapacitated sexual victimization related to alcohol and or drug intoxication, we could not disentangle the effects of alcohol from other substances. This was a sample of binge-drinking women with histories of victimization; the high-rates of revictimization may have reflected their high-risk status. The modified version of the SES potentially captured more severe sexual victimization than the CSVQ, which would only capture more severe episodes of revictimization at follow-up, which may have influenced the model’s ability to predict revictimization broadly. Finally, research on sexual victimization lacks a coherent definition of victimization, which makes it difficult to compare findings across studies.

The current study adds to our knowledge of specific alcohol-related risk factors for sexual revictimization and the unique risk posed by adolescent sexual victimization. Educational programming for college students about common consequences of blackouts and support regarding how to report victimization even if the victim does not fully remember the event are important steps to reducing revictimization risk for women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant R21AA016211 (PI: Kaysen). Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism training grant T32 AA07455-32.

References

- Chung T, Martin CS. Concurrent and discriminant validity of DSM-IV symptoms of impaired control over alcohol consumption in adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:485–492. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02565.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen CC, Palesh OG, Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2005;6:103–129. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087. doi:10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs-Lane AM, Smith DW. Risk of sexual victimization in college women: The role of behavioral intentions and risk-taking behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:165–183. doi:10.1177/0886260502017002004. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. Sexually victimized children. Free Press; New York, NY: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, Turner MG. The sexual victimization of college women. U.S. Department of Justice and the Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington, DC: 2000. Publication No. 182369. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/182369.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Coble CN, Latham L, Layman MJ. Sexual assault experience in adulthood and prior victimization experiences: A prospective analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1993;17:151–168. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1993.tb00441.x. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Loh C, Lobo T, Rich C, Lynn SJ, Pashdag J. Reciprocal relationships among alcohol use, risk perception, and sexual victimization: A prospective analysis. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:5–14. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.1.5-14. doi:10.3200/JACH.56.1.5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelein MJ. Risk factors for sexual victimization in dating: A longitudinal study of college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1995;19:31–48. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1995.tb00277.x. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey JA, White JW. Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00168-3. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA. Sexual Experiences Survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:422–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.422. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. The campus sexual assault (CSA) study. U.S. Department of Justice; Washington, DC: 2007. Publication No. 221153. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/221153.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Coates AA, Gaffey KJ, Johnson CF. Sexuality, substance use, and susceptibility to victimization risk for rape and sexual coercion in a prospective study of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1730–1746. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314336. doi:10.1177/0886260508314336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard school of public health college alcohol study surveys: 1993-2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. doi:10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Jamieson-Drake DW, Swartzwelder HS. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol-induced blackouts among college students: Results of an e-mail survey. Journal of American College Health. 2002;51:117–131. doi: 10.1080/07448480209596339. doi:10.1080/07448480209596339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault . Not alone. Author; Washington, DC: 2014. Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/report_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]