Abstract

Motivation: A basic problem of broad public and scientific interest is to use the DNA of an individual to infer the genomic ancestries of the parents. In particular, we are often interested in the fraction of each parent’s genome that comes from specific ancestries (e.g. European, African, Native American, etc). This has many applications ranging from understanding the inheritance of ancestry-related risks and traits to quantifying human assortative mating patterns.

Results: We model the problem of parental genomic ancestry inference as a pooled semi-Markov process. We develop a general mathematical framework for pooled semi-Markov processes and construct efficient inference algorithms for these models. Applying our inference algorithm to genotype data from 231 Mexican trios and 258 Puerto Rican trios where we have the true genomic ancestry of each parent, we demonstrate that our method accurately infers parameters of the semi-Markov processes and parents’ genomic ancestries. We additionally validated the method on simulations. Our model of pooled semi-Markov process and inference algorithms may be of independent interest in other settings in genomics and machine learning.

Contact: jazo@microsoft.com

1 Introduction

Recent developments in DNA technology bring personal genomics to reality. This opens up unprecedented possibilities for individuals to learn about their genomic history (e.g. ancestry, family history) as well as their genomic future (e.g. disease risk). A particular aspect of personal genomics that has garnered significant public and medical interest is the ability to precisely quantify the ancestry composition of one’s genome (Royal and Kittles, 2004; Royal et al., 2010).

Consider a Mexican individual as an example. Her genome consists of alternating blocks of DNA sequences, where each block has African, European or Native American ancestry. The length and frequency distributions of blocks from different ancestries reflect the patterns of admixtures over the last several centuries. A substantial fraction of humans today are offsprings of historical mixing between distinct populations and their genomes are such mosaics of ancestry blocks (Hellenthal et al., 2014).

The ability to quantify genomic ancestries has important bio-medical implications. For example, African ancestry is a risk factor for asthma. This partially explains the high prevalence of asthma in African American as well as Puerto Ricans with larger African genomic ancestry (Vergara et al., 2013). In addition, genomic ancestry gives insights into many social science questions, and expands the common notions of ethnicity and race (Bryc et al., 2015; Hochschild and Sen, 2015).

Given the genome of an individual, recent machine learning methods can accurately determine the fraction of this person’s genome that originates from each ancestry (Alexander et al., 2009; Pritchard et al., 2000). However, for many applications in biomedical and social science research, it is important to go beyond the individual’s ancestry and to infer the genomic ancestries of the parents (since most genetic datasets do not have genotype information from the parents). In studies of ancestry linked risk factors, genomic ancestry information of parents can be used to investigate how risks propagate through generations. In social science applications, parental genomic ancestry can be used to understand genetic basis of human mate selection, a subject of substantial recent interest. Latino parents, e.g. were shown to have significant correlations in their genomic ancestries (Risch et al., 2009).

However, current methods cannot be used to infer the genomic ancestry of each of the two parents of an individual given only the DNA of the individual. Inferring parental genomic ancestry is challenging since the observed DNA are unordered pools of the DNA from the two parents. We show that this problem of parental genomic ancestry inference can be well modeled as a pooled semi-Markov process. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first method that can accurately infer the parameters of the parental ancestries in admixed populations.

We applied the efficient algorithms we have developed for pooled semi-Markov process to infer parental ancestry. On experimental data from 231 Mexican families and 258 Puerto Rican families for whom we know the true genomic ancestry of each parent, we show that our method provides accurate estimates of parental genomic ancestry. Our method applies to any common genotyping data from an individual; importantly, no family or phasing information is needed, and hence it is broadly applicable to existing genetic data. Although in this article, we focus on the application of inferring genomic ancestry, we believe that many other settings can also be modeled as pooled semi-Markov process. For example in a tumor sample, there are many clonal subpopulations of cells, each with its own copy number aberrations which can be modeled as a semi-Markov process (Wu et al., 2014). When we sequence the tumor in clinics, we typically obtain a pooled collection of reads from the various subpopulations.

1.1 Contributions

Our main contributions are:

We set up the mathematical framework of pooled semi-Markov processes and construct efficient, scalable inference algorithms.

Using this framework of pooled semi-Markov processes, we develop a method to infer the parameters of the parental ancestries in admixed populations. This is important because it allows for a better understanding of how certain disease risks are associated with ancestries.

We demonstrate the accuracy of our method on a real genotype dataset of 489 families where we can measure the true genomic ancestry of each parent. We further validate it using simulations.

1.2 Related work

Semi-Markov models have been well studied in literature and have many applications ranging from economics to biology (Ross, 1999). A related class of models for sequential data is factorial HMMs (FHMMs) (Ghahramani and Jordan, 1997). FHMMs model outputs that are function of several hidden states where each hidden state evolves according to an independent Markov model. Because exact inference in FHMMs is intractable, a number of approximate inference procedures have been developed. The pooled semi-Markov process differs from FHMM in significant ways. First, the holding time in each HMM state is geometrically distributed, while we allow for arbitrary distributions. Second, the pooling model introduces hard combinatorial constraints that make standard variational inference inapplicable.

There is a large body of work on the inference of local ancestry in admixed populations, in which the ancestry of each position in the genome is inferred. These methods typically use hidden Markov chain models, (e.g. Price et al., 2009; Pritchard et al., 2000; Sankararaman et al., 2008a; Tang et al., 2006) variants such as switch HMMs (Sankararaman et al., 2008b) and factorial HMMs (Baran et al., 2012). Principal component analysis (PCA) has been shown to correlate well with global ancestry, and variants of PCA have been proposed (Yang et al., 2012). In the case of African-Americans, these models have been applied to show that African-Americans today are an admixture of African and European ancestries in the ratio 0.8:0.2 over the last 6–10 generations (Smith et al., 2004). Further, it has been shown that local ancestry can be accurately inferred in African-Americans. A limitation of these approaches is that they do not distinguish between the maternal and the paternal contributions to the genetic ancestry. Methods, such as Hapmix (Price et al., 2009), estimate the unordered pair of local ancestry states at each position but do not assign the local ancestry to each parental haplotype and hence do not tell us the genomic ancestries of each parent.

2 Methods

2.1 Pooled semi-Markov processes

A semi-Markov process generalizes continuous time Markov process to settings where the holding time in a state may not be exponentially distributed. We recall the generative procedure for sampling from a semi-Markov process of K states.

Definition —

Let f denote the probability density function of a random variable parametrized by λ (λ could represent either a scalar or a vector depending on the form of the density function). To sample from a K-state semi-Markov process parametrized by , we do the following:

.

Sample the state of the first block, .

Sample the length of the first block, .

We call the holding distribution of state k and a jump is a transition between two consecutive blocks. For our applications it is sufficient to work with this parametrization of the transitions using αk’s. All results can be extended to general semi-Markov process. The output sample is a chain of length L composed of blocks of distinct states. For the last block, we cut it off so that it stops at L. For , we denote by the state of the block that x belongs to, i.e. if x is in block i.

If f is the exponential distribution, then the corresponding semi-Markov process is equivalent to a continuous time Markov chain. For state k, the holding time is the time spent in that state and is an exponentially distributed random variable with rate λk. If we observe the states for an individual semi-Markov process and L is sufficiently long, then it is straightforward to perform maximum likelihood inference of the parameters . In genetics and other applications however, we do not observe each individual process but a pool of multiple semi-Markov processes where the identity of which process a given state is from is lost.

Definition —

Suppose we have M independent semi-Markov processes, each of length L. The j-th process is parametrized by and the state of the j-th process in position x is denoted by . The pooled semi-Markov process (abbreviated as PSMP) is obtained by the assignment of each to the K-dimensional vector of counts, , such that the k-th entry is number of elements in that equals to k. We call , the observations of the pooled semi-Markov process. The model is parametrized by .

We focus on continuous holding distributions f such that with probability 1 each process has a finite number of jumps in . Let N denote the sum of the number of jumps across all M processes. Then the continuous observations of the pooled semi-Markov process can be concisely described by the finite set , where is the counts vector observed at the i-th block across the M processes, and Li is the length of this block. Note that for continuous distributions, the probability that two blocks of two different semi-Markov chains end at the same point x is zero, thus with probability one and differ by one transition. When it is clear from context, we also use the equivalent representation .

Under a pooled semi-Markov process, the likelihood of the parameters Θ is

where is the unit vector with 1 in the entry and is the measure induced by the jth semi-Markov process. In the above integral, the set of hard constraints are finite (there being a single constraint for each of the N blocks). Nevertheless, these constraints make it intractable to exactly compute the likelihood in general. We develop efficient approximations below.

Example —

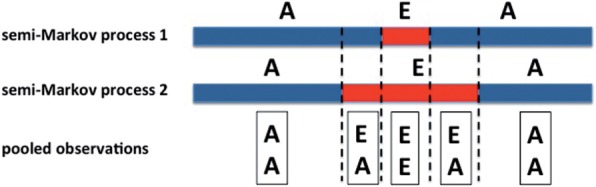

An application of the pooled semi-Markov process naturally arises in the field of population genetics. The diploid genome of an individual consists of one transmitted genome from each parent (the two segments in Fig. 1). The transmitted genome of each parent is a sequence of intervals, where each interval has a different genomic ancestry–(E)uropean, (A)frican, (N)ative American, etc. For example, if the mother is African American, then the genome that she passes on to the offspring is a mosaic of blocks of state A of some length distribution and state E of a possibly a different length distribution, and similarly for the father. Hence the genome passed from the mother to the offspring is well-modeled by a semi-Markov process (Donnelly, 1983; Gravel, 2012). When we genotype the offspring, say the one in Figure 1, we can infer that first region has ancestry AA and the second region has ancestry EA (using method described in the next section); however, we do not know whether the E part come from parent 1 or parent 2, and thus the information about the parents’ ancestry is lost. Given the pooled observations of the ancestries (e.g. AA, AE, EE) at every point in the genome, the goal is to infer the parameters for both parents. The λ’s parametrizes the length distribution of each ancestry state in a parent and the α’s capture the frequency of the ancestry states. With estimates for these parameters, we can infer the global ancestry of each parent, i.e. the fraction of the individual’s genome that is European, Native American or African, as well as the number of generations since the admixture.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of pooled semi-Markov process. A and E are the states and have different length distributions in the two semi-Markov processes

2.2 Algorithms for inference

We first consider the parameter estimation problem for pooled semi-Markov processes with exponential holding distributions (which are equivalent to continuous time Markov processes). Exponential holding distribution captures many of the genetic datasets of interests and can often be used as a reasonable approximation to other more complex distributions. We treat this problem in a Bayesian setting in which we place a prior on the parameter vector and for a given observation , we compute the posterior probability . We approximate the posterior using a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). To compute the likelihood as part of the MCMC, we developed a dynamic programming algorithm. In the next section, we show that this method gives accurate posterior estimates of the parameters of the model on genotype data from Mexican and Puerto Rican families.

For the non-exponential case, the dynamic programming algorithm needs to keep track of all the possible lengths for which a block of ancestry extends. This becomes expensive when the number of blocks, N, is large. Hence, we develop a more general stochastic- Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm to perform maximum likelihood inference on general pooled semi-Markov chains, as described in the next subsection. Note that there is an inherent symmetry in terms of which process we label as 1, 2, etc. that is not identifiable. Here we assume that the processes are labeled according to some arbitrary but fixed order, and the goal is to recover the parameters up to permutation of labels.

2.3 MCMC inference algorithm for pooled Markov process

For given observations and parameters , we use dynamic programming to compute the exact likelihood of the parameters, . For each , we keep track of all the distinct ordered states that are permutations of the observation . For example, if , then the consistent ordered states are (A, E), where state A is generated by process 1, and (E, A), where state A is generated by process 2. Note that we denote ordered states by and unordered states by . For a given unordered set , we denote by all the distinct ordered tuples that are consistent with . Here Si is the permutations of that give rise to distinct tuples. For each , let be the probability of observing in a pooled Markov chain parametrized by Θ. In other words, this is the probability of seeing the unordered observation up to i − 1 and then observing the ordered tuple . There are in the worst case KM such for each i.

For i = 1, if the ordered state is , then .

Given all the probabilities , we have

where are all the tuples that are one edit distance from π (since we know exactly one jump in one process has occurred between block i − 1 and i almost surely) and consistent with , and is the probability for transitioning from to , which can be computed analytically as a product of exponentials and ’s.

For example, suppose the states are E and A, and the observation at i is {E, E}. In this case there is just one tuple, (E, E), consistent with it, and

In the first term of the right hand side, is the contribution from continuing E with E in the first chain, and comes from continuing A with E in the second chain. And similarly for the second term of the right-hand side. Because there are two states in each chain, α’s do not appear.

Given this method for computing the likelihood of any observed data X for parameters , we use adaptive MCMC to compute the posterior distribution over Θ. The advantage of this approach is that we obtain full posterior distributions of Θ, and for several human populations, it gives accurate estimations (next section). A drawback is that computing the exact likelihood is expensive when the state space is large or when there are many chains—the run time is .

2.4 Stochastic EM inference algorithm for general pooled semi-Markov process

For general semi-Markov processes with non-exponential holding times, the dynamic programing would have to keep track of the last ordered state as well as its length, making it prohibitively expensive to compute the likelihood. We therefore propose a stochastic EM algorithm to perform parameter inference in general pooled semi-Markov processes. For each block i, the observation is the unordered set of states . Let be an M-by-N matrix where denote the process that generated the state at block i. is the matrix of the latent variables.

2.4.1 E-step

Given the current values of the parameters Θ and observations , it is in general intractable to compute the posterior . However we can generate samples from using an efficient sequential procedure using the expansion

For the base case, let , then

subject to the contraint that is a permutation of . This can be sampled efficiently using rejection sampling. The vector is one edit distance from , so that given there are at most KM-feasible values for . If vector differs from in index j, then can be computed as a function of the length of the current state for the j-th semi-Markov process and the ’s. Therefore we can explicitly compute the conditional probability of given for all values of . To sample we just sample from these conditional probabilities.

2.4.2 M-step

Given samples of the latent variables, we compute the maximum likelihood Θ by maximizing . Given , the parameters and are independent for different . For that r-th semi-Markov process, the optimization problem is . For standard distributions, this optimization can be solved analytically.

We iterate the E and M steps until convergence.

3 Results

3.1 Mexican and Puerto Rican trios

We used 231 Mexican mother-father-child trios and 258 Puerto Rican trios from the Genetics of Asthma in Latino Americans (GALA) study (Risch et al., 2009) For each trio, we have the genotypes of the two parents and the offspring across the entire genome. The trios were genotyped using the Affymetrix 6.0 GeneChip Array, which provides measurements of the genome at over 900 000 positions, called single nucleotide polymorphisms. Subjects were filtered based on call rates >95%, consistency between reported and genetic sex, and the absence of any unexpected identity by descent (IBD) or by state. Familial relationships were confirmed using measures of IBD and Mendelian inconsistencies.

We used LAMP-LD, a commonly used method, to infer the local ancestry state at each position in the genome in each individual (Baran et al., 2012). LAMP-LD uses a generative model in which the genome is divided into non-overlapping windows. An admixed genome is generated as an emission within each window from a HMM with states, where K is the number of ancestral populations. Transitions between the hidden states occur between adjacent windows. LAMP-LD computes a Viterbi decoding of the pairs of local ancestries along the genome. Since Puerto-Ricans and Mexicans have mixed ancestry with (E)uropean, (A)frican, and (N)ative American ancestries, LAMP-LD assigns to each position in the genome one of 6 states: EE, NN, AA, EA, EN and NA, depending on the ancestry of that position (e.g. NA corresponds to the case where one copy originated in Africa and the other in America).

In these datasets, we observed that the genomes of each of the parents are well approximated by exponential length distribution and hence by a Markov process. The genome of the child can then be modeled as a pooled Markov process, with M = 2 and K = 3. Note that in general, the genomes of the parents themselves cannot be modeled as a Markov process but as a semi-Markov process (Gravel, 2012). However in these data the exponential distribution proved to be a good approximation, likely because admixture occurred many generations ago in these samples and have been continuing ever since.

For the validation experiment, we take as input the observed local ancestry blocks of each offspring, and use the MCMC algorithm described earlier, with uniform priors, to infer the posterior distribution over the parameters of the model. In these data, the MCMC estimates are more accurate than estimates from the stochastic EM (not shown). There are six λ parameters and four independent α parameters. The global European (or African, Native American) genomic ancestry of an individual is defined to be the proportion of the total genome that is identified to be of European (or African, Native American) descent. For each set of parameters, we infer the global ancestry proportion of the corresponding parent by running a Markov chain with these parameters to equilibrium and computing the fractions. Then we compare the inferred global genomic ancestry of each parent with the true genomic ancestry of the parent computed explicitly by running LAMP-LD.

Genomes of Mexican samples contain primarily European (average of 43%) and Native American (49%) ancestries, and a small amount of African ancestry. In contrast, Puerto Ricans genomes contain mostly European (62%) and African (23%) ancestries, with a minor component of Native American. Moreover the two populations have distinct demographic histories leading to different statistical properties of their ancestries, corresponding to different distributions of and (Bryc et al., 2010). Hence these two datasets are complementary in exploring the performance of our approach under different conditions.

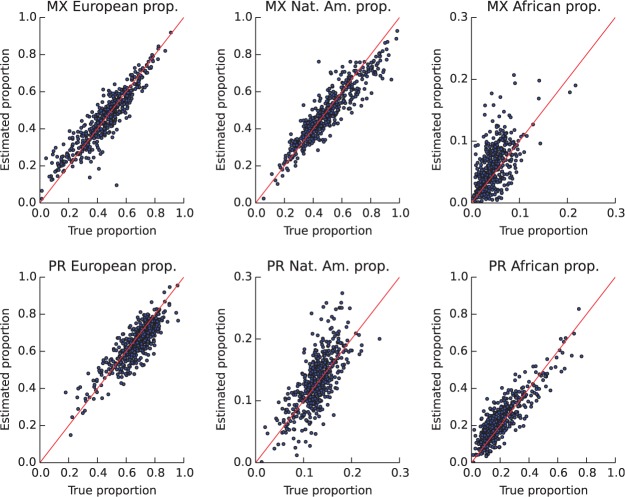

Table 1 contains the r2 between our estimated genomic ancestries using PSMP and the true genomic ancestries in the 462 Mexican (MX) parents and 516 Puerto Rican (PR) parents. We report the r2 for each of the ancestry states: European (E), Native American (N), African (A). In Mexican trios, our estimated proportions of European and Native American ancestries agree very well with the ground truth (coefficient of determination r2 = 0.84 for both). It performs worse in estimating the African proportion, likely because African blocks are only observed a few times in most samples. In Puerto Rican trios, our estimates for the European and African ancestries closely match the ground truth. It performs worse for the less frequent Native American ancestry (Figs. 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Ancestry estimation accuracy r2

| MX E | MX N | MX A | PR E | PR N | PR A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMP | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.35 | 0.72 | 0.5 | 0.75 |

| Offspring | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.66 |

| Independent | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.27 | 0.58 | 0.18 | 0.41 |

The first three columns correspond to the Euroean (E), Native American (N) and African (A) ancestries of the Mexican individuals. The last three columns correspond to the European, Native American and African ancestries of the Puerto Rican individuals.

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of the estimated genomic ancestry of each parent with the ground truth. The top row is for Mexican samples, each dot corresponding to one parent: European proportions (left), Native American proportions (middle) and African proportions (right). The bottom row is for Puerto Rican samples: European proportions (left), Native American proportions (middle) and African proportions (right)

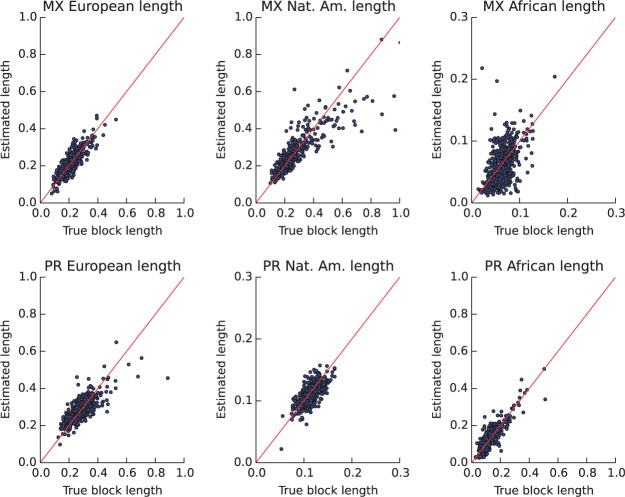

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of the estimated and true average block length of each ancestry type. The top row is for Mexican samples, each dot is one parent: average European block length (left), average Native American block length (middle) and average African block length (right). The bottom row is the average block length in Puerto Ricans for European (left), Native American (middle) and African (right) ancestries

In addition to accurately estimating the global genomic ancestries of each parent, our method also infers finer grained information. In particular, since the holding distributions are exponential, gives the average block length of each ancestry type in a parent. From standard coalescent models of population genetics, these length scales inform us the number of generations since the interbreeding of these populations in the family history of that individual. We compare the inferred length scales for each parent and ancestry type with the ground truth measured on the transmitted allele. In Mexicans, there’s strong correlation between length estimates from our method and the ground truth for European and Native American ancestries (r2 of 0.73 and 0.75, respectively). The estimate is less accurate for the less frequent African block lengths (r2 = 0.25). For Puerto Ricans, we find the strongest agreement in the block lengths of Africans (r2 = 0.75), followed by Europeans (r2 = 0.54) and Native Americans (r2 = 0.45).

3.1.1 Scalability

Our algorithms treat the samples independently and can be run in parallel on all the samples. For each human sample, it required ≤5 min on a standard desktop.

3.2 Comparison to benchmarks

In practice, it is often assumed that the genomic ancestry of the offspring is a good approximation of the ancestry of the parents. This only works if the genomic ancestries of the two parents are very similar, since the offspring’s ancestry essentially averages the parents’. This assumption is especially problematic in admixed populations (Latinos, African Americans, etc.) where the two parents may have very different ancestries. We tested this assumption in our trios, where we use the empirically measured genomic ancestry of the offspring as estimations of the parents’ ancestries. The correlation with the true genomic ancestries is reported in the second row of Table 1, and it is significantly worse than the results of the pooled semi-Markov process. For more heterogeneous populations, we expect the offspring to be even worse estimators of the parent’s ancestry.

The pooled semi-Markov process explicitly models the spatial correlation of nearby states. A simpler algorithm is to assume that all the observations are independent. The accuracy of this simpler model is reported in the third row of Table 1. It performs worse than the pooled semi-Markov process in all the categories and is especially poor in Puerto Ricans.

3.3 Simulations

3.3.1 Random trios

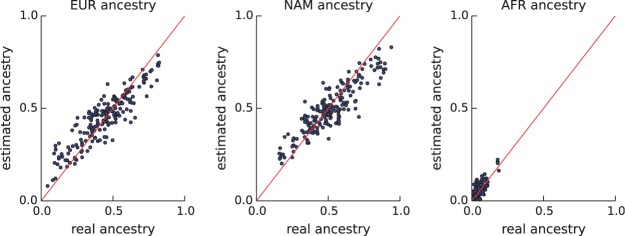

As an additional validation, we tested our algorithm on simulated Mexican male–female–offspring trios. In the actual trios, using the genotype of the three individuals, we inferred the transmitted allele from each parent to the offspring. To generate a random trio, we then randomly selected a male and a female parent and computationally combined their transmitted alleles to form a new offspring. This creates realistic offspring genotypes while preserving the complex demography encoded in the parents’ transmitted alleles. Using this process, we simulated 100 new trios for which we knew the true genomic ancestry of each individual. As before, we applied our method to the offspring data to infer the ancestries of the parents. Comparison of the inferred ancestries with the ground truth showed very good agreement (Fig. 4). For the European, Native American and African ancestries, we achieved r2 of 0.9, 0.89 and 0.77, respectively.

Fig. 4.

On simulated Mexican trios, comparisons of the estimated genomic ancestry of each parent with the ground truth. Each dot corresponds to one parent. The x-value shows the actual ancestry of the parent and the y-value shows the inferred ancestry. European, Native American and African ancestries are shown in the left, middle and right panels, respectively

3.3.2 Non-exponential chains

We also investigated how well we can do inference on pooled semi-Markov processes where the distributions are very different from exponential, as these could be relevant for other demographic models and applications. We consider the particular case where the block lengths of each state are Gaussian distributed. We use the more general stochastic EM algorithm given above to perform inference.

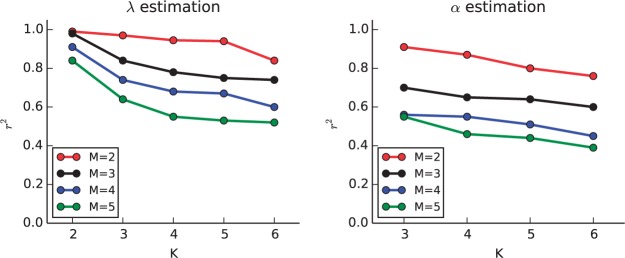

In the experiments, we varied and . For each combination of K and M, we simulate 50 pools of semi-Markov processes. We consider unit variant Gaussians with mean λk. For each process, we sampled uniformly from the K-dim simplex and sample λk uniformly from [5, 10]. Different processes in the same pool have different α’s and λ’s. Each observed dataset is created by pooling M different Gaussian semi-Markov processes. To better match the quantity and noise of realistic genomic data, we use only the first N = 500 blocks of the pooled semi-Markov process as observations. This is the input into our stochastic EM algorithm. To evaluate the estimation, we compute the r2 between the estimated λ’s and the true λ’s and between the estimated and true α’s, across all pools and all processes. The results are summarized in Figure 4. For M = 2, 3, we obtain accurate estimations for even large numbers of states, with r2 > 0.8. The accuracy of inference declines as the number of processes in a pool increases. In these more complex models, we can improve our accuracy by collecting larger number of observations (N) from each pool (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Experimental validation of inference for λ (left) and α (right) for pooled Gaussian semi-Markov processes. The X axis corresponds to the number of states K and different line colors correspond to different number of processes M. For the α estimations, K = 2 is trivial since all the α’s are 0.5, and is omitted

4 Discussion

We developed an efficient method to infer the genomic ancestry of the parents from the genotype of an offspring. We applied our method to genotype data of 231 Mexican and 258 Puerto Rican individuals to infer the parents’ ancestries. We showed that the method is highly accurate by comparing the inferred ancestries with each parent’s true genomic ancestries. We further validated the method on simulated trios. For pooled Markov processes, we showed how to compute likelihood exactly using dynamic programming. For general pooled semi-Markov processes, we developed a stochastic EM algorithm to infer the model parameters. We additionally validated accuracy of our inference algorithm in settings where the semi-Markov length distributions are Gaussians.

We tested our algorithm on Latino trios, but it can be applied to other admixed populations and can be used to infer ancestries other than European, Native American and African. The method can be used on general genotype datasets of unrelated, unphased individuals, for which large cohorts exist, to infer the genomic ancestries of the parents. This has immediate applications in investigating assortative mating in human populations.

The current approach assumes that the local ancestry of the offspring has been computed from his/her genotype. This is reasonable for large admixed populations such as Latinos and African Americans, where existing algorithms (e.g. LAMP-LD) can accurate infer the local ancestries. For other admixed populations, an interesting direction of future work is to jointly infer the local ancestry of the offspring and the global ancestries of the parents

Funding

EH is a faculty fellow of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Bioinformatics at Tel Aviv University. EH was partially supported by the Israeli Science Foundation (grant 1425/13), by the National Science Foundation grant III-1217615, and by the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation (grant 2012304).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Alexander D.H., et al. (2009) Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. , 19, 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baran Y., et al. (2012) Fast and accurate inference of local ancestry in latino populations. Bioinformatics , 28, 1359–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryc K., et al. (2015). The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am. J. Hum. Genet. , 96,37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryc K., et al. (2010) Genome-wide patterns of population structure and admixture among Hispanic/Latino populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. , 107,8954–8961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly K. (1983) The probability that related individuals share some section of genome identical by descent. Theor. Popul. Biol. , 23, 34–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahramani Z., Jordan M.I. (1997) Factorial hidden markov models. Mach. Learn., 29, 245–273. [Google Scholar]

- Gravel S. (2012) Population genetics models of local ancestry. Genetics , 191,607–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellenthal G., et al. (2014) A genetic atlas of human admixture history. Science , 343, 747–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild J., Sen M. (2015) Singular or multiple? The impact of genomic ancestry testing on Americans racial identity. The Du Bois Review. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Price A.L., et al. (2009) Sensitive detection of chromosomal segments of distinct ancestry in admixed populations. PLoS Genet. , 5, e1000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J., et al. (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics , 155, 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N., et al. (2009) Ancestry-related assortative mating in latino populations. Genome Biol. , 10, R132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S. (1999) Stochastic Processes. Routledge, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Royal D., et al. (2010) Inferring genetic ancestry: opportunities, challenges, and implications. Am. J. Hum. Genet. , 86, 661–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal M., Kittles R. (2004) Genetic ancestry and the search for personalized genetic histories. Nat. Rev. Genet. , 5, 611–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankararaman S., et al. (2008a) Estimating local ancestry in admixed populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. , 8, 290–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankararaman S., et al. (2008b) On the inference of ancestries in admixed populations. Genome Res. , 18, 668–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M.W., et al. (2004) A high-density admixture map for disease gene discovery in African Americans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. , 74, 1001–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., et al. (2006) Reconstructing genetic ancestry blocks in admixed individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. , 79, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara C., et al. (2013) African ancestry is a risk factor for asthma and high total ige levels in African admixed populations. Genet. Epidemiol. , 37,393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., et al. (2014). Detecting independent and recurrent copy number aberrations using interval graphs. Bioinformatics , 30, i195–i203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., et al. (2012). A model-based approach for analysis of spatial structure in genetic data. Nat. Genet. , 44, 725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]