Abstract

With the global aging population, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and mild cognition impairment are increasing in prevalence. The success of rapamycin as an agent to extend lifespan in various organisms, including mice, brings hope that chronic mTOR inhibition could also refrain age-related neurodegeneration. Here we review the evidence suggesting that mTOR inhibition - mainly with rapamycin - is a valid intervention to delay age-related neurodegeneration. We discuss the potential mechanisms by which rapamycin may facilitate neurodegeneration prevention or restoration of cognitive function. We also discuss the known side effects of rapamycin and provide evidence to alleviate exaggerated concerns regarding its wider clinical use. We explore the small molecule alternatives to rapamycin and propose future directions for their development, mainly by exploring the possibility of targeting the downstream effectors of mTOR: S6K1 and especially S6K2. Finally, we discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the models used to determine intervention efficacy for neurodegeneration. We address the difficulties of interpreting data using the common way of investigating the efficacy of interventions to delay/prevent neurodegeneration by observing animal behavior while these animals are under treatment. We propose an experimental design that should isolate the variable of aging in the experimental design and resolve the ambiguity present in recent literature.

Keywords: Aging, Healthspan, Intervention, mTOR, Neurodegeneration, Prevention, Rapamycin

1. Introduction

Although it is clear that the most prominent risk factor for neurodegeneration is age, investigation of this deleterious process remains primarily outside of the context of aging. In 2013 the American National Institute on Aging organized a geroscience summit with the objective of decreasing the isolation between the aging and disease-focused Institutes. Despite this initiative, age-related diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and others all continue to be mainly studied under non-aging context. We think that there is much to learn from successful health-span interventions. Indeed, if these interventions are successful at slowing down the aging process, it is reasonable to think that they would also delay the apparition of age-related pathologies. This is especially true for neurodegeneration which seems to be a slowly acquired phenotype that, to date, is apparently irreversible. Thus far, the most successful pharmaceutical intervention to slow down aging is the use of rapamycin in rodents. In this review, we will discuss specifically how rapamycin could potentially delay neurodegeneration by delaying aging, as well as the promise for rapamycin to potentially reverse neurodegeneration. Studying neurodegeneration and its behavioral effects in rodents is quite complex. Small molecule intervention can lead to data interpretation confusions if the acute and chronic effects of the molecules are not dissociated. We propose specific modifications to current anti-aging protocols using small molecules and explain how we feel these modifications could prevent controversy regarding the positive effects of rapamycin in relation to its capacity to delay both aging and neurodegeneration. Though a successful intervention, rapamycin poses some problems because of its sides effects; we discuss routes of investigations in order to reduce these side effects.

1.1. Relevance for New Drug Targets and Future of Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease

We think that mTOR is a valid target to investigate for the prevention and treatment of age-related neurodegeneration. Rapamycin is currently a clinically useful small molecule, yet more investigation is needed to confirm its utility in anti-aging intervention. We hope that this review will aid in the pursuit of these ideas and also will help guide the design of more precise interventions for investigators to draw unambiguous conclusions about their experiments.

1.2. Neurodegeneration as an Age-Related Disease

As median lifespan continues to rise, the prevalence of age-related neurodegenerative disorders will do the same. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common of the neurodegenerative diseases and the sixth leading cause of death amongst the aged population. Concern grows to find disease modifying interventions since AD is predicted to affect 1 in 85 people globally by 2050 [1]. The primary risk factor for AD is aging, as the overwhelming majority of individuals who have the disease (∼95%) are age 65 or older [2] and the rate of development of AD doubles roughly every five years from this point, peaking at a nearly 50 percent population prevalence by age 85 [3]. Notably, the rate of disease in women is 1.5 to 3 times as high as that in men, as estrogen deficiency in the brain (generally brought on by menopause) has been linked to AD [4, 5]. AD manifests progressive impairments in memory and language and is pathologically characterized by extracellular amyloid plaques (Aβ) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) composed of hyperphosphorylated tau [6]. Though the exact cause (s) of AD are unknown, there are a number of known risk factors associated with development of the disease. The largest known genetic risk factor for sporadic AD is inheritance of Apolipoprotein epsilon-4 (APOE-4), one of the 3 forms of the APOE gene [7]. Individuals who carry two copies of the e-4 allele have a higher risk than those who carry only one copy, and both groups have a higher risk than those who carry only the e-2 or e-3 forms [8]. While the exact reason for increased risk is unclear, it is known that APOE enhances proteolytic clearance of Aβ and that the e-4 variant is less efficient at catalyzing this reaction than the e-2 or e-3 forms [9]. It is noteworthy that being an APOE-4 carrier does not guarantee development of AD, and lacking APOE-4 is not preventative, suggesting that factors other than Aβ burden may have significant impact on disease symptomology.

While AD is the most prevalent age-associated neurodegenerative disorder, it is by no means the only one. Parkinson's disease (PD), the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, affects around 7 million people globally [10] and is characterized by movement disorders including rigidity, tremor, and gait abnormalities, as well as incidences of cognitive disturbances and dementia resulting from impaired dopamine production in the substantia nigra due to cell death. Similarly to AD, the cause of PD is not currently known, though age appears to be the primary determinant. The average age of onset for PD is 60, with fewer than 10% of cases developing prior to age 50 [11]. Accordingly, the prevalence of PD is elevated in the elderly, with nearly 4% of individuals over the age of 80 affected compared to only 1% of the 60 year old population [10]. Though AD and PD are the most common age-associated neurodegenerative disorders, many other subcategories exist, including vascular dementia (VD), Lewy body dementia (DLB), and Frontotemporal lobar dementia (FTLD). Interestingly, while the exact causes of these neurodegenerative disorders remain elusive, they all share the common feature of an age-mediated increase in susceptibility to pathology and there is significant overlap in the symptoms of these disorders, suggesting that a common mechanism may mediate disease progression and/or may be exploited to alleviate symptoms.

In this regard, one particularly striking feature common to these disorders is an overall reduction in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and impaired vessel reactivity, resulting in neurovascular uncoupling. Proper brain function demands rapid and proportional increases in oxygen and glucose to active brain regions, and it is no surprise that this mechanism is disrupted in both ‘healthy’ aging [12] and to a greater extent in neurodegenerative disease [13-15]. Notably, conditions associated with poor physical fitness that can damage the heart or blood vessels, including high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, high cholesterol [16], orglucoregulatory abnormalities (i.e. type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)) [17-20] increase the risk for developing AD [17]. It is noteworthy that these conditions are themselves pathologies of aging, further emphasizing the link between biological aging and neurodegeneration.

1.3. Aging and mTOR

Aging is characterized by a tissue degenerescence and loss of function. Important efforts have been made to understand the molecular and cellular events leading to this progressive degenerescenceas evidenced by the fact that the number of publications on aging has steadily increased since 1960. Just as it did for neurodegeneration, the field has more recently benefitted from a sustained exponential growth in the number of publications since 2000. These studies have revealed several molecular pathways involved in longevity, termed longevity pathways, which have been conserved through evolution and, in reality, promote aging and lead to enhanced longevity when inhibited or abrogated [21]. These generally include pathways integrating growth signals from the environment; indeed, growth factor receptor, insulin receptor and mTOR pathway inhibition all lead to lifespan extension in various species. Incidentally, caloric restriction is arguably the most studied lifespan extending intervention [21]; recent work suggests that mTOR inhibition may mimic caloric restriction [22, 23]. This effect is probably due to a reduced IGF1 signaling [22] and perhaps in addition, due a minimizing the presence of amino acids that would normally activate mTOR has posited here [23].

The integration of growth and nutrient signals from the environment converge on the mTOR pathway, which has been extensively studied in the context of aging and its downregulation systematically leads to lifespan extension [24]. mTOR is a kinase of the phosphatidylinositol kinase-related kinase family [25]. mTOR is the catalytic subunit of two functionally and structurally distinct complexes. The core components of each complex include mTOR andmLST8/GβL and each also associates with DEPTOR which inhibits mTORC1 and can be inactivated via phosphorylation by mTOR [26]. The complexes differ in several associated proteins - primarily Raptor and PRAS40 (mTORC1) or Rictor and mSIN1 (mTORC2). mTORC1 functions as a nutrient sensor that can be activated by insulin, growth factors, and amino acids [27] and is sensitive to inhibition by rapamycin. As opposed to its activation by nutrients, mTORC1 activity is repressed by low energy levels; this repression is mediated by the AMP-activated protein kinase and ultimately leads to autophagy activation [28]. mTORC2, on the other hand, is known to be involved in cytoskeleton organization [29], can activate Akt and is generally insensitive to rapamycin, though long term treatment has been shown to inhibit mTORC2 both in cell culture [30] and in mice [31]. Notably, the mechanism of mTORC2 inhibition was recently shown to be mediated by the expression of various FK506-binding proteins, specifically the ratio of FKBP12 to FKBP51; reduction of FKBP12 expression through transfection of shRNA successfully alleviates mTORC2 inhibition by rapamycin in PC3 cells. Perhaps even more pertinent, reduction of FKPB12 expression in both HeLa and HEK 293T cells (which exhibit low FKBP12 expression to begin with) not only blocks inhibition of mTORC2 but also completely abrogates inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin, suggesting that FKBP levels are crucial to the variable responses observed across different cell types following rapamycin treatment [32].

mTORC1 is activated by the PI3Kinase - AKT pathway. As a result of this activation, mTORC1 phosphorylates the kinases ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 and 2 (S6K1 and S6K2) and eIF-4E binding protein 1 through 4 (4E-BP 1, 2, 3 and 4). The main outcomes of these activations are the promotion of global translation and cap-dependent translation supporting both cellular growth and proliferation [5, 33]. While the regulation of mTORC2 remains unclear, several of its substrates are known, including AKT, SGK and PKC-α, all of which are important for cell proliferation and survival [34-36]. As mentioned above, AKT is upstream of mTORC1, meaning that mTORC2 activation contributes to the sustained activation of mTORC1 as well. Adding further complexity, mTORC1 mediates the downregulation of PI3K signaling via Grb10 phosphorylation [37, 38]. In addition, S6K1 triggers a negative feedback loop through inactivation of insulin receptor signaling, thus inhibiting the mTORC1 pathway [39, 40]. This complex interplay makes it difficult to cast in vivo predictions on the outcome of long term mTOR inhibition.

1.4. mTOR in Neurodegeneration

Given the prominent role of mTOR in aging, the pressing question is whether mTOR will serve as a viable target to prevent aging-related neurodegeneration. This idea stems from: a) the discovery that mTOR inhibition increases lifespan in a number of different models, b) aging as the primary risk factor for neurodegeneration, and c) the known role of mTOR in memory formation, a process that is commonly disrupted in multiple forms of neurodegeneration. Previous work has shown that mTORC1 is required for late-phase long term potentiation (LTP) [41] in the Schaffer collateral pathway [42], and separate studies showing that rapamycin could impair long-term consolidation of rodent fear memory [43] and hippocampus-dependent spatial memory [44] confirm that mTOR activity is necessary tomemory formation mediated by multiple brain regions. Furthermore, mTOR activity has been noted to promote the synthesis of dendritic proteins within hippocampal neurons [45]. However, while mTOR activity appears necessary to memory, hyperactive mTOR is capable of disrupting memory formation as well. One study investigated transgenic mice modelling tuberous sclerosis and found that the animals exhibited both overactive mTORC1 and memory impairment which were subsequently normalized by treatment with rapamycin [46]. Similarly, humans with mutations to TSC1 or TSC2 exhibit increased mTOR activity and subsequent memory dysfunction [46]. Furthermore, studies on cannabinoid-mediated memory impairment show that rapamycin administration during cannabinoid ingestion alleviates disruption of hippocampus-mediated memory formation by decreasing enhanced mTOR activity [47]. Thus, multiple research groups have suggested that there may be an optimal window of mTOR activity to facilitate memory formation and therefore proper dosing is imperative for studies utilizing rapamycin [48-51].

With this in mind, dysregulated mTOR signaling is observed in multiple neurodegenerative disorders [51]. For example, mTOR has been found to be hyperactive in both in vitro and in vivo [49] AD models as well as in affected brain areas from human subjects [52]. Notably, mTOR hyperactivation in these models appears to be mediated, at least in part, by beta-amyloid (Aβ), as reduction of Aβ in the 3×Tg-AD mouse model was sufficient to reverse mTOR hyperactivity when accomplished using either intrahippocampal injection of an Aβ antibody or by simply cross-breeding transgenic animals with non-transgenic mice to reduce the amyloid burden [49]. Also noteworthy is that active mTORC1 has been observed to increase translation of tau [52, 53], while drosophila overexpressing tau exhibit increased mTORC1 activity [54]. Taken together, one could posit that dysregulation of mTOR may be a triggering event in an aberrant feed-forward loop that promotes NFT formation in AD. Consistent with this idea, PDAPP and 3×Tg-AD mice treated with rapamycin exhibit reduced overall brain levels and aggregation of both Aβ and tau concomitant with a restoration of normal mTOR activity and rescue of cognitive deficits [48, 55]. There is evidence that Aβ is degraded through autophagy [56, 57] and that this process is impaired in both human AD subjects and transgenic mice modelling the disease [58].

Neurodegenerative diseases can broadly be classified as disorders of protein folding in which improperly assembled proteins form aggregates and inclusions that infringe upon cellular function. While the affected proteins differ between diseases, the routes of clearance remain the same. Under normal circumstances, damaged or unnecessary proteins are degraded via two major pathways: the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, in which proteins are covalently tagged by an ubiquitin chain and rapidly degraded by a proteasome, or the lysosomal pathway, in which the protein is enveloped by a lysosome containing proteases and other digestive enzymes. Under starvation conditions, when nutrients are not readily available to the cell, a specific type of lysosomal degradation known as autophagy takes place wherein cellular components are broken down and recycled for new protein synthesis. One of the primary known functions of mTOR is the suppression of autophagy [59], while a number of studies have indicated impaired autophagy in post-mortem brain samples of various neurodegenerative diseases [60-63] wherein autophagosomes are inadequately cleared [63-65]. Thus, it is feasible that facilitating the clearance of aberrant misfolded proteins by increasing autophagy may provide a clinically relevant and beneficial effect in a multitude of neurodegenerative disorders.

1.5. Rapamycin: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Action

Rapamycin was discovered from a soil sample collected from Easter Island and is produced by a strain of Streptomyces hygroscopicus [66]. Originally, rapamycin was approved by the FDA as an immunosuppressant as it potently achieved this action in multiple animal and human models of organ transplant [67], though the utility of rapamycin in various diseases has also been attributed to significant antiproliferative [68] and antifungal [69] properties and more recently has shown potential as an agent to enhance cognitive function in both healthy and neurodegenerative disease state models [70, 71]. The underlying molecular mechanism of these actions lies in rapamycin's ability to interfere with activation of mTORC1 by forming a complex with FKBP and binding directly to mTOR, thereby inhibiting a number of mTOR-mediated signal transduction pathways [72]. mTOR activation can lead to translation initiation via eIF4E, transcription through either S6K or cdk2/Cyclin E activation, and suppression of autophagy. For a detailed review of these mechanisms, see the review by Sehgal [73].

1.6. Rapamycin as an Intervention in Neurodegenerative Disease

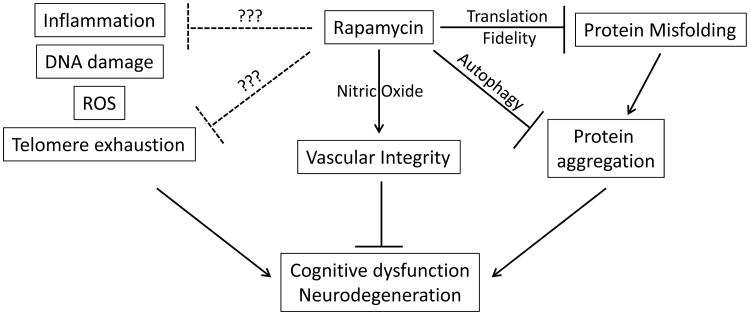

Notably, rapamycin has been found to facilitate autophagy through both the induction of autophagosome formation and the subsequent enhancement of lysosomal biogenesis [56, 62]. Accordingly, many recent studies suggest the enhanced induction of autophagy by rapamycin as the mediator of its beneficial effects in neurodegenerative disease (Fig. 1). One study using the MPTP model of Parkinson's disease showed that autophagosomes accumulated in the midbrain following MPTP injection; rapamycin treatment restored lysosome-mediated clearance of the autophagosomes and reduced dopaminergic cell death in the substantia nigra [62]. Additionally, alpha synuclein, a primary component of Lewy body plaques observed in PD, is known to be degraded in part through autophagy, and cell culture experiments using mutated alpha synuclein demonstrated increased aggregation when autophagy was inhibited [74], further suggesting that enhanced autophagy may provide benefit to individuals with PD.

Fig. (1). Rapamycin effects to prevent neurodegeneration.

The induction of autophagy by rapamycin has been credited with alleviating pathology in other neurodegenerative diseases as well. A number of studies have suggested that in Huntington's disease, the mutant huntingtin protein appended with a massive poly-glutamine extension can be cleared through autophagy [56, 75]. Findings reported on mice modeling Huntington's treated with the rapamycin ester temsirolimus also point toward increased autophagy. These animals demonstrated reduced mTOR activity and improved motor function as well as decreased aggregation of huntingtin protein in the brain [56]. Interestingly, autophagy generally declines during the aging process. Dysfunctional chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) has significant effects on protein homeostasis and contributes to metabolic dysfunction in aging mice; notably, genetic manipulation that prevents the age-associated decrease in CMA in mouse liver improves hepatocyte function and homeostasis [76], while disruption of CMA in young but not old mice can be compensated for by both macroautophagy and proteosomal pathways [77], suggesting that deficient autophagy significantly contributes to the aging process. In C. elegans, the natural decline in autophagy accelerates once the organism has passed its reproductive period; it is important to note that reproductive span has been shown to correlate with overall lifespan in this model [78]. While it is a leap to apply these findings to humans, it is conceivable that autophagy may significantly decrease following menopause in women which could contribute to the increased incidence of AD in human females compared to males [4].

While autophagy is the main route of clearance for misfolded proteins, it is important to consider other mechanisms that may contribute to this process. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a build-up of beta-amyloid within blood vessels leading to impaired vessel integrity and brain hemorrhage, is present in greater than 80% of AD cases [79]. This condition is known to impair blood flow and is at least partially responsible for the overall reduction in cerebral blood flow (CBF) observed in AD brains [80]. As such, enhancement of vessel dilation would likely prove beneficial in two ways; first, by counteracting the effects of amyloid aggregation within vessels, and second, by facilitating the clearance of amyloid from the vessels and into the perivascular drainage. In this regard, rapamycin has previously been shown to increase CBF in symptomatic J20 AD mice by a mechanism that involves enhanced local production of nitric oxide (via eNOS) resulting in vessel relaxation [71].

1.7. Three Approaches to Neurodegeneration Intervention

There are three different ways to approach neurodegeneration. As with every age-related disease, the first approach is prevention. Indeed, if we accept the premise that aging is the primary risk factor for neurodegeneration, then it naturally follows that interventions that delay aging will have widespread repercussions in delaying or preventing neurodegenerative disease. Such an idea is not unfounded; an assertion has previously been made that a hypothetical intervention that delays the onset of AD by just 5 years would result in a 57% reduction in the number of patients with AD and reduce projected Medicare costs by nearly $300 billion [19]. Of course, this type of intervention must preclude the apparition of the disease and would likely involve treating ostensibly healthy subjects. The second approach is to slow down the progression of the disease once it is already established. As it relates to AD, this approach has recently gained favor as many experts agree that the disease pathogenesis begins years and possibly even decades before subjects become symptomatic [81] and therefore interventions that can ameliorate or attenuate disease progression will likely have the greatest utility. Finally, the third approach is to reverse the progression of the disease and repair damage that has already occurred, eventually constituting a cure. As explained above, rapamycin may provide some utility in all three approaches.

1.8. Side Effects of Rapamycin

Until more clarity is shed on why decreasing mTOR activity leads to an improved healthspan, it will be difficult to design the best regimen intervention for neurodegeneration prevention. For now, we rely on empirical evaluation optimizing for the maximum beneficial effect with minimal side effects. Based on both human clinical data and on mouse models, the main side effects of rapamycin are ulcerative wounds to the mouth and throat (in humans) [82] and hyperlipidemia [83], though other effects including testicular atrophy, immunosuppression, insulin resistance, and impaired wound healing have been observed [84]. Additionally, mice chronically treated with rapamycin also suffer from early cataract formation [85]. How rapamycin induces cataract formation in mice, testicular atrophy and wound healing decline is not well understood but the antiproliferative activity of rapamycin is a likely contributor to the latter two side effects [84].

If there is still information missing in order to understand how mTOR inhibition by rapamycin leads to healthspan increase, there is just as much to learn in regards to what causes its side effects. Even though rapamycin is labeled as an immuno-suppressant by the FDA, the mechanism of immune suppression is not very well characterized. For an enlightening look at the effects of mTOR signaling in T helper lymphocytes, see Delgoffe and Powell 2012 [86]. Rapamycin is primarily given to kidney graft transplant patients receiving other immunosuppressants like cyclosporine, making it difficult to isolate the effect of rapamycin itself. Conversely, immunostimulatory effects of rapamycin have been documented. Indeed, rapamycin stimulates the functional qualities of memory T cells in mice and thereby helps to fight viral infection [87]. Incidentally, a recent clinical study showed that RAD001 (a rapamycin derivative) can rejuvenate the response to vaccination in the elderly [88]. In the latter study, rapamycin was used for 6 weeks followed by 2 weeks off drug prior to vaccination; RAD001 enhanced the vaccination response by 20%. Of the 22 parameters investigated, only mouth ulceration was reported to occur at higher incidence in rapamycin treated subjects than those receiving a placebo. This clinical study was relatively small (53 individuals per group) so extrapolation should be taken with caution. Nonetheless, together these findings suggest that the immunosuppressive concern for rapamycin may be exaggerated. Insulin resistance is another issue found to be the result of prolonged use of rapamycin [84]. This effect appears to be due to a disruption of mTORC2 [30] as long term rapamycin treatment leads to mTORC2 inhibition in culture and in vivo [30, 89]. It is noteworthy that the effect of rapamycin on skeletal insulin resistance may be reversible, as Liu et al demonstrate that cessation of rapamycin treatment abrogates the observed glucose intolerance within 2-3 weeks in mice of varying backgrounds [90].

1.9. Intermittent Treatment to Avoid Side Effects of Rapamycin

Rapamycin is the most studied small molecule intervention in regards to slowing down aging progression and preventing or postponing neurodegeneration. Though it is already approved by the FDA for life threatening conditions, it is unlikely to be approved for chronic use by healthy individuals unless its side effects are minimal. Notably, healthy C57BL/6J mice chronically treated with rapamycin beginning at 4 months of age exhibit significantly better learning and memory than controls in the Morris water maze (MWM) task [70] and also improved memory in old (25 months) but otherwise healthy C57BL/6J mice in the passive avoidance task [70], suggesting that rapamycin may confer cognitive benefits even in healthy aging. Still, incomplete understanding of the molecular mechanisms leading to the side effects of rapamycin appears to have prevented the scientific community from designing a safer yet efficacious intervention schedule. One can draw some conclusions from the kinetics of the manifestation and disappearance of side effects following withdrawal. Because hepatic insulin resistance is due to long-term treatment and can be uncoupled from lifespan extension, shorter and intermittent treatment is a very appealing solution [30, 89].

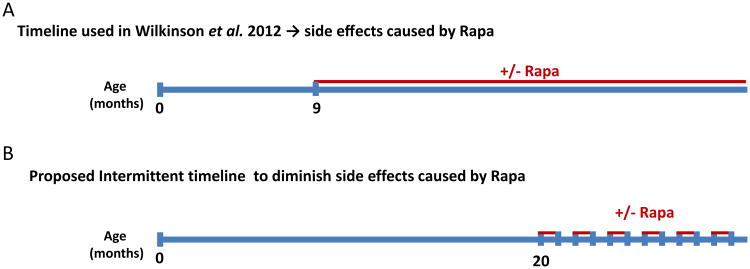

We know that an intermittent treatment such as 2 weeks on, 2 weeks off has already been shown to successfully extend the lifespan of female mice [91], although side effects were not reported by this study. Chronic treatment using the 14 ppm regimen started at nine months of age extends lifespan but also leads to side effects in mice [85], while the same treatment started at 18 months of age confers comparable lifespan extension and side effects [92] suggesting that persistent, chronic treatment is not necessary to mediate the beneficial effects. Treatment for only 6 weeks starting at 22 months of age reduced the mortality rate of these mice, though the relationship to overall lifespan was not explored in these studies as the subjects were terminated [93]. Dosage wise, increasing the concentration to 42 ppm increases longevity even further, particularly in males who do not benefit much from the lower 14 ppm dose [94]. With the exception of one study demonstrating short term (3 weeks and 3 months) low dose (14 ppm) intervention at 3-6 or 18-21 months of age in genetically heterogeneous HET3 mice led to glucose intolerance (despite normal insulin tolerance) [95], the studies of late intervention or higher dose (42 ppm) did not report on the side effects; still the available evidence pleas for an intervention starting at a later age and the higher 42 ppm dose with intermittent treatment. The National institute of Health Interventions Testing Program (ITP) will soon initiate such a schedule where the intermittence will be one month on - one off (Fig. 2) (Dr. Nancy Nadon, NIH/NIA, personal communication to RML). This intervention regimen and schedule could be tested for the aforementioned side effects as well as efficacy for both increasing healthspan and neurodegeneration prevention. In light of the importance of the differences between 14 and 42 ppm of rapamycin, it may be advantageous to consider even higher doses in the future.

Fig. (2). Rapamycin intervention schedule in mice.

A. Chronic intervention schedule used in Wilkinson et al. leading to side effect. Treatment starts a 9 months of age and is continuous until death of the animal. B. Proposed intervention scheduled to alleviate the side effect of rapamycin. Treatment is initiated at 20 months of age. Rapamycin is given for 1 month and then the mouse is withdrawn from it for a month. The cycle is repeated every month.

It is very possible that current treatment regimens with rapamycin could be used to prevent age-associated neurodegeneration and other aging pathologies in both animal models and human subjects. Such work is already being undertaken in various labs and emerging results are very promising; most notably work done on the J20 AD mouse model showing maintained cognition in mice chronically treated with rapamycin compared to untreated mice who suffered from cognitive decline [55]. Importantly, treatment in this study was initiated after the onset of cognitive symptoms, suggesting that rapamycin treatment may be able to reverse symptomatic AD-like memory deficits. Of note, similar studies in the 3×Tg mouse model found that the induction of autophagy with rapamycin after the onset of symptoms (15 months) did not have any discernible effect on either pathology or cognitive function in this model [96], though a significant reduction in these areas was observed when treatment was begun earlier in life. These findings support the assertion that there is an optimal level of mTOR activity as well as an optimal window for treatment to be effective. Still, while the results observed in the J20 model are promising, potential side effects remain a concern, particularly for human subjects. As such, intermittent treatment may serve as a viable option to resolve the potential immunosuppressive effects of rapamycin in humans. Of course, even in the case of intermittent treatment it would be advisable for subjects to immediately cease treatment at any sign of infection or impaired wound healing. In both cases treatment could be resumed once the threat has passed.

1.10. Beyond Rapamycin

In order to increase specificity, pharmacokinetic properties, or to broaden the scope of activity, several other small molecules targeting mTOR have been developed [89]. Molecules analogous to rapamycin -rapalogs-may have better PK properties but continue to target the same mTORC1 complex and therefore are expected to yield similar results to rapamycin. If rapamycin can bind directly to mTORC1 this interaction is favored by orders of magnitude when rapamycin first binds to FK-binding protein-12 [97]. This interaction, mTOR-rapamycin-FKBP12, hinders the catalytic cleft of mTORC1 and thereby strongly inhibits the phosphorylation of S6Ks [98]. To alleviate the requirement for FKBP12 and to allow a better inhibition of 4EBP phosphorylation, catalytic inhibitors of mTOR such as Torin and PP242 have been developed, though they have not yet been studied in the context of aging [99, 100]. Since these inhibitors do not interact with FKBP12, potential side effects originating from its sequestration should be circumvented. The mTOR kinase inhibitors are not specific for mTORC1, and because mTORC2 inhibition leads to insulin resistance, it is likely that these inhibitors would lead to the same side effects [101]. In the context of aging, the dosing schedule would have to be finely adjusted accordingly. The recent finding that FKBPs are essential for the inhibition of mTORC2 by rapamycin reinforces the need to find new molecules working independently of FKBPs so specific mTORC1 inhibition can be achieved [32].

1.11. Beyond mTOR - Lessons from S6K1 and S6K2

As mentioned above, S6K1 and S6K2 are the downstream targets of mTOR that are the most affected by rapamycin. If their inhibitions are responsible for the positive effects of rapamycin, one would expect that ablation or reduction of these proteins would recapitulate the beneficial effects of rapamycin. This has turned out to be the case as S6K1 null mice benefit from lifespan extension, though S6K1 knockout works only in female mice and has side effects in terms of cognition [102, 103]. S6K2 KO has not yet been tested in the context of aging but does not cause the same learning deficits that result from S6K1 knockout [103] as S6K2 knockout mice do not suffer from these cognitive deficits [103]. We may find out in the future that S6K2, a downstream effector of mTOR, is responsible for the beneficial effects of rapamycin and that being further downstream, it will have fewer side effects.

1.12. Rapamycin and Healthspan: Controversy and Solution

As described above, an overwhelming accumulation of evidence suggests a positive effect of chronic rapamycin treatment to delay signs of aging and neurodegeneration in mice. However, it has been suggested that rapamycin would act on some aging phenotypes irrespective of aging [104]. These are the conclusions of a comprehensive study evaluating several parameters associated with aging in mice upon chronic rapamycin treatment. This study corroborates what has already been seen by others in regards to aging but added an interesting turn where these rejuvenation effects not only occurred in the old animals but also in the young ones. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that rapamycin was not delaying aging per se but was able to enhance a phenotype that typically declines with age. These conclusions have been disputed elsewhere, mainly based on the assertion that the effects of rapamycin in old animals are so profound that rapamycin must delay aging and more importantly, because rapamycin extends the maximum lifespan of mice it therefore must have true anti-aging action [105, 106]. Notably, rapamycin delays the apparition of cancer and because mice die primarily from cancer, it could be argued that rapamycin extends the average lifespan via this effect [92, 104]. However, if the oldest mice to die do not show signs of cancer the argument does not hold. Future experiments using strains which do not predominantly die of cancer should be informative in this regard.

Regardless, given that rapamycin has a similar phenotypic effect in young animals who have not yet experienced the systemic changes of aging, this interpretation may be flawed. Unfortunately, while it is simple to test the effects of chronic rapamycin treatment in young animals, this will not provide many answers as to how rapamycin effectively delays aging in older animals as the baseline viability of various systems is different between these groups. A similar effect seen in both young and old animals brings questions about the effect of the drug in delaying aging but does not provide an answer. As such, the experimental design used by Neff et al. [104] does not adequately address the question of preventing age-related decline.

1.13. Behavioral Testing in Mice to Evaluate Neurodegeneration: Strengths and Weaknesses

It is important to note that cognitive behavioral testing is only one way to measure the systemic effects of potential age- or neurodegeneration-preventing interventions. There are, of course, innumerable measures at the cellular and molecular level that can be altered by drug treatments (e.g. electrophysiological readings, gene and protein expression profiles, etc.) that provide valuable insights into the mechanism of action of an intervention, and we do not want to overshadow the importance of these studies or the information that can be gleaned from them. However, entire reviews have been dedicated to these techniques and their interpretations, and therefore for the sake of brevity we will not address them here and have instead chosen to focus on the endpoint measure of cognition in animal models.

As research moves forward using animal models of neurodegenerative disease, it is important to remember that naturally occurring aging-related neurodegeneration is rarely seen in species other than humans. There are certain aspects of brain aging that are recapitulated in non-human primates and other mammals, but these species do not truly develop correlates to the neurodegenerative diseases that plague elderly humans [107]. Still, transgenic techniques allow the investigation of the neuropathological lesions that are inherent to these diseases, and thus are a valuable tool. The underlying assumption, of course, is that these pathological hallmarks are causal in the subsequent cognitive deficits observed in neurodegenerative disease; this assumption is generally validated as significant cognitive deficits have been observed in various rodent disease models by numerous labs. As a result, cognitive behavioral testing is widely employed in mice modeling various neurodegenerative diseases to assess the extent and progression of cognitive deficits as well as the effectiveness of potential interventions. The majority of these tasks rely on hippocampus-dependent learning and memory as the primary observable symptom in neurodegenerative disease is a deficiency in these abilities [108]. Because rodent and other animal models are unable to verbally communicate, the majority of the commonly utilized behavioral paradigms rely on motor function and instinct-driven motivations to assess cognitive function. As such, it is imperative that the behavioral task chosen for an experiment take into account physical limitations [109] that may be conferred by the disease state being modeled as well as potentially confounding factors such as anxiety or depression that might impinge upon motivation to perform the task.

Just the same, treatment interventions that may ameliorate any of these factors, and therefore improve performance on the task, may be misinterpreted to have improved cognition. For example, antidepressants have been found to improve cognitive performance in human subjects in multiple studies [110, 111], though the degree to which the declared cognitive enhancement may have been affected by improvement in subject motivation or alertness has been disputed as cognition, motivation, and emotion are intricately related [112]. In this regard, individuals who suffer from anxiety have been shown to exhibit an attentional bias to threatening stimuli and have difficulty refocusing their attention once such a stimulus has passed [113]. Recent efforts have been made to statistically correct for the extent of depression in human studies to account for these factors, but doing so in animal studies requires proper screening. Thus, it is imperative that appropriate controls such as the Forced Swim Test or Tail Suspension Test be utilized to measure and account for confounds such as anxiety and depression, and researchers must be cautious when suggesting that a compound or other intervention enhances cognition. This point is perfectly illustrated in the case of rapamycin, which has been shown to have both antidepressant and anxiolytic effects but is also associated with enhanced cognition and improved longevity. For a comprehensive description of methodological considerations when designing animal behavior experiments as well as in depth descriptions of several popular paradigms, see Bailey and Crawley [114]. Still, when properly performed and interpreted, behavioral testing has been invaluable in confirming cognitive deficits in neurodegeneration models as well as for identifying potential interventions.

Contextual fear conditioning (FC) is widely used to assess hippocampus-dependent memory in rodent disease models. There are various methods of training and testing in this paradigm, though all are a variant of Pavlovian conditioning and involve placing the subject in a novel environment and then pairing an aversive stimulus (typically an electric shock delivered through the floor of the chamber) with a neutral stimulus (commonly a tone or white noise). The animal is later returned to the chamber and freezing behavior, which is the fear response in rodents, is measured. Animals that exhibit a high percentage of freezing during the testing trial are interpreted to have formed an association or memory of the context of the chamber, whereas animals that do not freeze or explore freely are considered to be impaired in the task. Numerous labs have found various AD mouse models to be deficient in this task (for a review of these and other findings regarding cognitive deficits in AD mouse models, see Puzzo et al[108]), and several compounds associated with restoration of cognitive function have been shown to restore the freezing response. Contextual FC is one of the strongest behavioral assessments in regards to confounds and interpretations, as the task taps into a very strong, innate response and the animal either freezes or it does not and thus there is little room for interpretation. However, the strength of the association is also a limitation of the task, as contextual FC can only be performed one time in an animal as the effects are very long lasting. It is possible to extinguish the context association by repeatedly re-training the subject without administering the aversive stimulus, but this adds a great deal of time to the experiment and the number of trials required to extinguish the association may be affected by strain and treatment. As such, it is difficult to utilize FC to investigate progressive cognitive decline in a neurodegeneration model since different time points must be taken using different animals.

Another commonplace cognitive task is novel object recognition (NOR), a hippocampus-dependent spatial memory task. This task takes advantage of the innate rodent infatuation with novelty by training the animal with two identical objects contained in an arena. The subject is allowed to freely explore both the arena and the objects, with the amount of time exploring each object recorded (Exploration is typically defined as the animal being oriented toward the object and within a relatively short distance e.g. 1cm). Since the objects are identical, the expectation is that roughly equivalent time will be spent exploring each object. 24 hours later, the subject is returned to the arena, but this time one of the objects has been replaced with something new. Since rodents are inherently curious, the expectation is that a cognitively functional mouse will spend a greater amount of time inspecting the ‘novel’ object than it will on the familiar object that it had seen the day before. Thus, NOR is often utilized as a memory task, particularly with AD models, as cognitively impaired animals will inspect the familiar object with the same fervor as the novel one, suggesting that the supposedly familiar object is not recognized and indicating a memory deficit. In addition to being a relatively simple experiment to perform, NOR provides a major advantage in that it can be performed multiple times in the same animal by simply changing out the objects being used. While this task is fairly straightforward, though, there are limitations - most notably finding several objects that the strain being tested is sufficiently interested in but without a particular preference for any one object. It is also important to consider motor function when analyzing NOR data as a more mobile mouse may explore the arena more thoroughly or an impaired mouse might sit near one object and mistakenly be characterized as exploring.

One of the most utilized behavioral tests for assessing hippocampus-dependent spatial learning and long-term spatial memory is the Morris water maze (MWM). As with FC, many groups have used the MWM to demonstrate cognitive impairments in various AD mouse models [115, 116] and aging [70, 117]. For a review on MWM methodology, see Vorhees et al. [118]. Briefly, mice are placed into a swimming pool filled with opaque water high enough to conceal the location of a submerged ‘escape’ platform. Stationary cues are placed around the outside of the pool to facilitate navigation. Mice are allowed to swim in the pool for 1 minute or until they find the platform. They will repeat this task several times on each training day, being originally placed in the pool at different locations so that they do not simply learn a motor pattern that leads them to the platform. Over the course of several days it is expected that subjects will progressively improve both the time it takes to reach the platform as well as the total distance swam before reaching it. After several days of training, the platform is removed for a probe trial in which the subject is allowed to swim freely for 45 seconds and the number of times they cross the previous platform location is recorded. The expectation is that mice that have learned to navigate to the platform will cross the previous location multiple times in an attempt to find it, whereas those that have not learned will swim somewhat aimlessly for the duration of the trial. MWM is a good indicator of both learning capacity and memory, though there are a number of factors that can result in poor performance. The task was originally developed for testing spatial memory in rats who are natural swimmers and thrive in a water environment [119], while mice are burrowers and thus perceive water as a mortal threat. As such, they are more likely to exhibit thigmotaxis (swimming near the edge of the pool) [118] and passive floating behavior [120] which can artificially alter swimming distance, time, and swim speed. Also, mice that exhibit increased anxiety or depression may be more likely to exhibit these behaviors, while interventions with anxiolytic or anti-depressant effects may attenuate them, and therefore it is imperative that such variables be considered when interpreting MWM data. Still, MWM is a useful paradigm to assess cognitive deficits in AD mouse models, particularly in older animals [115, 116].

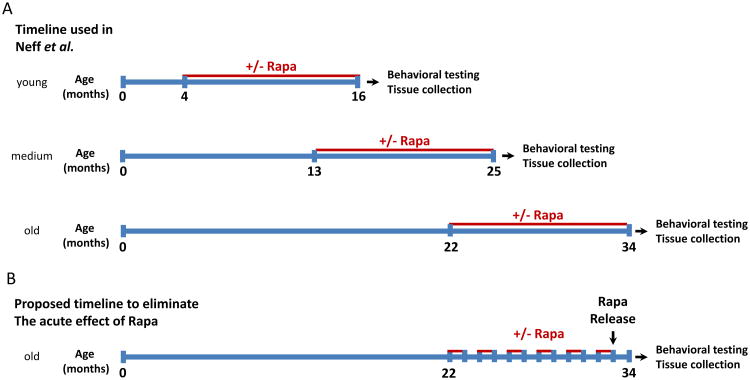

We should learn a lesson from the Neff et al study [104]. In order to answer the question as to whether rapamycin or any other drug delays aging, it is not sufficient to chronically give the drug to an animal and then study if there are some behavioral advantages of the treatment. Behavioral studies are complex and involve multiple systems in an organism and are therefore influenced by multiple factors. The problem is that testing behavior in a subject that is still under the influence of the compound can significantly alter the results of a study. As mentioned above, rapamycin binds to FKBP12, which binds to ryanodine receptors and influences excitable cell functions [121]. Since ryanodine receptors are present in neurons, it is predictable that rapamycin treatment will acutely affect behavior through modulation of cell excitability [122]. In fact, these behavioral changes are readily observed in FKBP12 knockout mice [123]. The effect observed by Neff on young animals may well be due to the acute effects of rapamycin on behavior- this may also be the case in old animals. There are obviously advantages to maintaining an intervention during testing as it allows for longitudinal studies and thus increases statistical power and lowers the cost of experiments. However, doing so does not allow for the separation of the acute versus chronic effects of treatment that may differentially impinge upon the outcome. The solution here is simple: wean the animal of the intervention long enough to erase any potential acute effect from the drug before conducting behavioral testing. The remaining effect can be narrowed down to aging prevention or delay in a pure aging model. The intermittent treatment proposed above in Fig. (2) is helpful in this regard as it allows testing during withdrawal time. For an intervention where intermittent treatment would not be possible, withdrawal would have to be done at the end of the experiment prior to cognitive behavioral testing (Fig. 3). Admittedly, this picture becomes a bit more complicated in a neurodegeneration model as it will not be possible to differentiate between improvements due to delayed aging compared to those resulting from delaying or preventing a neuropathogenic process to which aging contributes. The choice of a month of drug holiday for an optimum experimentation is based on willingness to balance; minimum side effects, maximum healthbenefits and minimum behavioral confounding factors. A single dose of rapamycin has a 2 months effect on rats feeding behavior [124]. While this study emphasizes the need for a withdrawal from the compound before performing any behavioral test, it also suggests that a 1 month withdrawal might not be enough. A similar study conducted in mice would be need to determine this. As the ITP perform the intermittent dosing experiments, they should also collect data on feeding behavior, doing so it will be possible to determine if 1 month is enough to eliminate behavioral acute effect. This of course assumes that all behavioral effects are on the same schedule.

Fig. (3). Rapamycin mouse interventions with and without the acute effect of rapamycin.

A. Chronic intervention schedule used in Neff et al. for young, medium and old animals. Behavioral testing and tissue collection are performed while rapamycin is still present in the animal. B. Proposed chronic intermittent intervention where rapamycin is withdrawn for a month before performing Behavioral testing and collecting tissues. The intervention is started at 22 months of age for the sake of comparison.

Conclusion

Despite the recent controversy suggesting that mTOR modulation by rapamycin does not extend healthspan and prevent neurodegenaration, a wealth of evidence at the tissue level suggests that it does. As the field devises conclusions in this direction, mTOR modulation as an intervention in human neurodegeneration is worth consideration. Rapamycin is labeled as an immunosuppressant which makes it a tough sell clinically. However, this label originated from its usage rather than from its true mechanism, which, as mentioned above, may not be entirely immunosuppressive in the classic sense of the term and may instead be a side effect that can be circumvented once the mechanism of anti-aging is identified. Rapamycin nonetheless has side effects that should be considered before starting any trials. As study continues we may find that the dosage and treatment schedule optimal for the beneficial effects of rapamycin to be less aggressive than current clinical standard [84] and that an intermittent schedule would likely help in reducing side effects. In addition, several rapalogs and other mTOR inhibitors are being developed that may confer a better safety profile than rapamycin itself. Neurodegeneration is a terrible problem affecting the lives of many. Efforts to find treatments have not yet provided adequate or substantial interventions and thus prevention is an attractive route. Delaying the apparition of neurodegenerative disease using mTOR inhibitors is appealing and should be considered in this context. No intervention is without risk, but we must ask ourselves, do the benefits of potentially delaying the onset of neurodegenerative disease outweigh these risks?

Acknowledgments

RML is supported by the US National Institute of Health (National Institute on Aging), K99AG045288. JBJ is supported by the US National Institute of Health, 2T32AG021890-11.

List of Abbreviations

- Aβ

Beta amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- APOE4

Apolipoprotein E4

- CAA

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- CBF

Cerebral blood flow

- DLB

Lewy body dementia

- eNOS

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- FC

Fear conditioning

- FDA

Food and drug administration

- FKBP

FK506 binding protein

- FTLD

Fronto-temporal lobar dementia

- ITP

Interventions testing program

- LTP

Long term potentiation

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- mTOR

Mechanistic target of rapamycin

- mTORC1/2

Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1/2

- MWM

Morris water maze

- NFT

Neurofibrillary tangle

- NOR

Novel object recognition

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- S6K1/2

Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1/2

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TSC 1/2

Tuberous sclerosis complex 1/2

- VD

Vascular dementia

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(3):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brookmeyer R, Gray S, Kawas C. Projections of Alzheimer's disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(9):1337–1342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris JC. Is Alzheimer's disease inevitable with age?: Lessons from clinicopathologic studies of healthy aging and very mild alzheimer's disease. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(9):1171–1173. doi: 10.1172/JCI8560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandy S, Duff K. Post-menopausal estrogen deprivation and Alzheimer's disease. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35(4):503–511. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson VW. Estrogens, episodic memory, and Alzheimer's disease: a critical update. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27(3):283–293. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1216281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballard C, Gauthier S, Corbett A, Brayne C, Aarsland D, Jones E. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2011;377(9770):1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadigh-Eteghad S, Talebi M, Farhoudi M. Association of apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele with sporadic late onset Alzheimer's disease. A meta-analysis. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 17(4):321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slooter AJ, Cruts M, Kalmijn S, Hofman A, Breteler MM, Van Broeckhoven C, van Duijn CM. Risk estimates of dementia by apolipoprotein E genotypes from a population-based incidence study: the Rotterdam Study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(7):964–968. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.7.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang Q, Lee CY, Mandrekar S, Wilkinson B, Cramer P, Zelcer N, Mann K, Lamb B, Willson TM, Collins JL, Richardson JC, Smith JD, Comery TA, Riddell D, Holtzman DM, Tontonoz P, Landreth GE. ApoE promotes the proteolytic degradation of Abeta. Neuron. 2008;58(5):681–693. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2006;5(6):525–535. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samii A, Nutt JG, Ransom BR. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2004;363(9423):1783–1793. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin AJ, Friston KJ, Colebatch JG, Frackowiak RS. Decreases in regional cerebral blood flow with normal aging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11(4):684–689. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson NA, Jahng GH, Weiner MW, Miller BL, Chui HC, Jagust WJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Schuff N. Pattern of cerebral hypoperfusion in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment measured with arterial spin-labeling MR imaging: initial experience. Radiology. 2005;234(3):851–859. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343040197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Goekoop R, Stam CJ, Scheltens P. Altered resting state networks in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer's disease: an fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;26(4):231–239. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertrand E, Lewandowska E, Stepien T, Szpak GM, Pasennik E, Modzelewska J. Amyloid angiopathy in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Folia Neuropathol. 2008;46(4):255–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szekely CA, Breitner JC, Zandi PP. Prevention of Alzheimer's disease. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(6):693–706. doi: 10.1080/09540260701797944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer disease and decline in cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(5):661–666. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson C, Feightner JW, Garcia A, Hsiung GY, MacKnight C, Sadovnick AD. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 1. Risk assessment and primary prevention of Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2008;178(5):548–556. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craft S. The role of metabolic disorders in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia: two roads converged. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(3):300–305. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span--from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328(5976):321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercken EM, Crosby SD, Lamming DW, Je Bailey L, Krzysik-Walker S, Villareal DT, Capri M, Franceschi C, Zhang Y, Becker K, Sabatini DM, de Cabo R, Fontana L. Calorie restriction in humans inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway and induces a younger transcription profile. Aging Cell. 2013;12(4):645–651. doi: 10.1111/acel.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharp ZD, Strong R. The role of mTOR signaling in controlling mammalian life span: what a fungicide teaches us about longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(6):580–589. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamming DW. Diminished mTOR signaling: a common mode of action for endocrine longevity factors. Springer Plus. 2014;3:735. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moding EJ, Kastan MB, Kirsch DG. Strategies for optimizing the response of cancer and normal tissues to radiation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(7):526–542. doi: 10.1038/nrd4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson TR, Laplante M, Thoreen CC, Sancak Y, Kang SA, Kuehl WM, Gray NS, Sabatini DM. DEPTOR is an mTOR inhibitor frequently overexpressed in multiple myeloma cells and required for their survival. Cell. 2009;137(5):873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, King JE, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110(2):163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ. The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nature cell biol. 2011;13(9):1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/ncb2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr biol. 2004;14(14):1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamming DW, Ye L, Katajisto P, Goncalves MD, Saitoh M, Stevens DM, Davis JG, Salmon AB, Richardson A, Ahima RS, Guertin DA, Sabatini DM, Baur JA. Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity. Science. 2012;335(6076):1638–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.1215135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schreiber KH, Ortiz D, Academia EC, Anies AC, Liao CY, Kennedy BK. Rapamycin-mediated mTORC2 inhibition is determined by the relative expression of FK506-binding proteins. Aging Cell. 2015;14(2):265–273. doi: 10.1111/acel.12313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dowling RJ, Topisirovic I, Alain T, Bidinosti M, Fonseca BD, Petroulakis E, Wang X, Larsson O, Selvaraj A, Liu Y, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Sonenberg N. mTORC1-mediated cell proliferation, but not cell growth, controlled by the 4E-BPs. Science. 2010;328:1172–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.1187532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307(5712):1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Martinez JM, Alessi DR. mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) controls hydrophobic motif phosphorylation and activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1) Biochem J. 2008;416(3):375–385. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikenoue T, Inoki K, Yang Q, Zhou X, Guan KL. Essential function of TORC2 in PKC and Akt turn motif phosphorylation, maturation and signalling. EMBO J. 2008;27(14):1919–1931. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu PP, Kang SA, Rameseder J, Zhang Y, Ottina KA, Lim D, Peterson TR, Choi Y, Gray NS, Yaffe MB, Marto JA, Sabatini DM. The mTOR-regulated phosphoproteome reveals a mechanism of mTORC1-mediated inhibition of growth factor signaling. Science. 2011;332(6035):1317–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.1199498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu Y, Yoon SO, Poulogiannis G, Yang Q, Ma XM, Villen J, Kubica N, Hoffman GR, Cantley LC, Gygi SP, Blenis J. Phosphoproteomic analysis identifies Grb10 as an mTORC1 substrate that negatively regulates insulin signaling. Science. 2011;332(6035):1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.1199484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah OJ, Wang Z, Hunter T. Inappropriate activation of the TSC/Rheb/mTOR/S6K cassette induces IRS1/2 depletion, insulin resistance, and cell survival deficiencies. Curr Biol. 2004;14(18):1650–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tzatsos A, Kandror KV. Nutrients suppress phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling via raptor-dependent mTOR-mediated insulin receptor substrate 1 phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(1):63–76. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.63-76.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swiech L, Perycz M, Malik A, Jaworski J. Role of mTOR in physiology and pathology of the nervous system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784(1):116–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang SJ, Reis G, Kang H, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Schuman EM. A rapamycin-sensitive signaling pathway contributes to long-term synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(1):467–472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012605299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parsons RG, Gafford GM, Helmstetter FJ. Translational control via the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway is critical for the formation and stability of long-term fear memory in amygdala neurons. J Neurosc. 2006;26(50):12977–12983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4209-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dash PK, Orsi SA, Moore AN. Spatial memory formation and memory-enhancing effect of glucose involves activation of the tuberous sclerosis complex-Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. J Neurosc. 2006;26(31):8048–8056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0671-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gong R, Park CS, Abbassi NR, Tang SJ. Roles of glutamate receptors and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway in activity-dependent dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(27):18802–18815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ehninger D, Han S, Shilyansky C, Zhou Y, Li W, Kwiatkowski DJ, Ramesh V, Silva AJ. Reversal of learning deficits in a Tsc2+/- mouse model of tuberous sclerosis. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):843–848. doi: 10.1038/nm1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puighermanal E, Marsicano G, Busquets-Garcia A, Lutz B, Maldonado R, Ozaita A. Cannabinoid modulation of hippocampal long-term memory is mediated by mTOR signaling. Nat Neurosc. 2009;12(9):1152–1158. doi: 10.1038/nn.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caccamo A, Majumder S, Richardson A, Strong R, Oddo S. Molecular interplay between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), amyloid-beta, and Tau: effects on cognitive impairments. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(17):13107–13120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caccamo A, Maldonado MA, Majumder S, Medina DX, Holbein W, Magri A, Oddo S. Naturally secreted amyloid-beta increases mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity via a PRAS40-mediated mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(11):8924–8932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garelick MG, Kennedy BK. TOR on the brain. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46(2-3):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bove J, Martinez-Vicente M, Vila M. Fighting neurodegeneration with rapamycin: mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Neurosc. 2011;12(8):437–452. doi: 10.1038/nrn3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li X, Alafuzoff I, Soininen H, Winblad B, Pei JJ. Levels of mTOR and its downstream targets 4E-BP1, eEF2, and eEF2 kinase in relationships with tau in Alzheimer's disease brain. FEBS J. 2005;272(16):4211–4220. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.An WL, Cowburn RF, Li L, Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Iqbal K, Iqbal IG, Winblad B, Pei JJ. Up-regulation of phosphorylated/activated p70 S6 kinase and its relationship to neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(2):591–607. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63687-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khurana V, Lu Y, Steinhilb ML, Oldham S, Shulman JM, Feany MB. TOR-mediated cell-cycle activation causes neurodegeneration in a Drosophila tauopathy model. Curr Biol. 2006;16(3):230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spilman P, Podlutskaya N, Hart MJ, Debnath J, Gorostiza O, Bredesen D, Richardson A, Strong R, Galvan V. Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin abolishes cognitive deficits and reduces amyloid-beta levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e9979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ravikumar B, Vacher C, Berger Z, Davies JE, Luo S, Oroz LG, Scaravilli F, Easton DF, Duden R, O'Kane CJ, Rubinsztein DC. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36(6):585–595. doi: 10.1038/ng1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jaeger PA, Wyss-Coray T. All-you-can-eat: autophagy in neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pickford F, Masliah E, Britschgi M, Lucin K, Narasimhan R, Jaeger PA, Small S, Spencer B, Rockenstein E, Levine B, Wyss-Coray T. The autophagy-related protein beclin 1 shows reduced expression in early Alzheimer disease and regulates amyloid beta accumulation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(6):2190–2199. doi: 10.1172/JCI33585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dunlop EA, Tee AR. Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1: signalling inputs, substrates and feedback mechanisms. Cell Signal. 2009;21(6):827–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nixon RA, Wegiel J, Kumar A, Yu WH, Peterhoff C, Cataldo A, Cuervo AM. Extensive involvement of autophagy in Alzheimer disease: an immuno-electron microscopy study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64(2):113–122. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anglade P, Vyas S, Javoy-Agid F, Herrero MT, Michel PP, Marquez J, Mouatt-Prigent A, Ruberg M, Hirsch EC, Agid Y. Apoptosis and autophagy in nigral neurons of patients with Parkinson's disease. Histol Histopathol. 1997;12(1):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dehay B, Bove J, Rodriguez-Muela N, Perier C, Recasens A, Boya P, Vila M. Pathogenic lysosomal depletion in Parkinson's disease. J Neurosc. 2010;30(37):12535–12544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1920-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chu Y, Dodiya H, Aebischer P, Olanow CW, Kordower JH. Alterations in lysosomal and proteasomal markers in Parkinson's disease: relationship to alpha-synuclein inclusions. Neurobiol dis. 2009;35(3):385–398. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boland B, Kumar A, Lee S, Platt FM, Wegiel J, Yu WH, Nixon RA. Autophagy induction and autophagosome clearance in neurons: relationship to autophagic pathology in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosc. 2008;28(27):6926–6937. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0800-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vila M, Bove J, Dehay B, Rodriguez-Muela N, Boya P. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in Parkinson disease. Autophagy. 2011;7(1):98–100. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.1.13933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sehgal SN. Rapamune (RAPA, rapamycin, sirolimus): mechanism of action immunosuppressive effect results from blockade of signal transduction and inhibition of cell cycle progression. Clin Biochem. 1998;31(5):335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(98)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sehgal SN, Molnar-Kimber K, Ocain TD, Weichman BM. Rapamycin: a novel immunosuppressive macrolide. Med Res Rev. 1994;14(1):1–22. doi: 10.1002/med.2610140102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Douros J, Suffness M. New antitumor substances of natural origin. Cancer Treat Rev. 1981;8(1):63–87. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(81)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martel RR, Klicius J, Galet S. Inhibition of the immune response by rapamycin, a new antifungal antibiotic. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1977;55(1):48–51. doi: 10.1139/y77-007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Halloran J, Hussong SA, Burbank R, Podlutskaya N, Fischer KE, Sloane LB, Austad SN, Strong R, Richardson A, Hart MJ, Galvan V. Chronic inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin by rapamycin modulates cognitive and non-cognitive components of behavior throughout lifespan in mice. Neuroscience. 2012;223:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin AL, Zheng W, Halloran JJ, Burbank RR, Hussong SA, Hart MJ, Javors M, Shih YY, Muir E, Solano Fonseca R, Strong R, Richardson AG, Lechleiter JD, Fox PT, Galvan V. Chronic rapamycin restores brain vascular integrity and function through NO synthase activation and improves memory in symptomatic mice modeling Alzheimer's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(9):1412–1421. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brown EJ, Albers MW, Shin TB, Ichikawa K, Keith CT, Lane WS, Schreiber SL. A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex. Nature. 1994;369(6483):756–758. doi: 10.1038/369756a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sehgal SN. Sirolimus: its discovery, biological properties, and mechanism of action. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(3 Suppl):7S–14S. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Webb JL, Ravikumar B, Atkins J, Skepper JN, Rubinsztein DC. Alpha-Synuclein is degraded by both autophagy and the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(27):25009–25013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sarkar S, Krishna G, Imarisio S, Saiki S, O'Kane CJ, Rubinsztein DC. A rational mechanism for combination treatment of Huntington's disease using lithium and rapamycin. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(2):170–178. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang C, Cuervo AM. Restoration of chaperone-mediated autophagy in aging liver improves cellular maintenance and hepatic function. Nat Med. 2008;14(9):959–965. doi: 10.1038/nm.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schneider JL, Villarroya J, Diaz-Carretero A, Patel B, Urbanska AM, Thi MM, Villarroya F, Santambrogio L, Cuervo AM. Loss of hepatic chaperone-mediated autophagy accelerates proteostasis failure in aging. Aging Cell. 2015;14(2):249–264. doi: 10.1111/acel.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang MC, Oakley HD, Carr CE, Sowa JN, Ruvkun G. Gene pathways that delay Caenorhabditis elegans reproductive senescence. PLoS Genetics. 2014;10(12):e1004752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jellinger KA. Prevalence and impact of cerebrovascular lesions in Alzheimer and lewy body diseases. Neurodegener Dis. 2010;7(1-3):112–115. doi: 10.1159/000285518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Greenberg SM, Gurol ME, Rosand J, Smith EE. Amyloid angiopathy-related vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke. 2004;35(11 Suppl 1):2616–2619. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143224.36527.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morris JC. Early-stage and preclinical Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Dis. 2005;19(3):163–165. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000184005.22611.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jozwiak L, Ksiazek A. Painful crural ulcerations and proteinuria as complications after several years of therapy with mTOR inhibitors in the renal allograft recipient: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2013;45(9):3418–3420. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Holdaas H, Potena L, Saliba F. mTOR inhibitors and dyslipidemia in transplant recipients: A cause for concern? Transplant Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stallone G, Infante B, Grandaliano G, Gesualdo L. Management of side effects of sirolimus therapy. Transplantation. 2009;87(8 Suppl):S23–26. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a05b7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wilkinson JE, Burmeister L, Brooks SV, Chan CC, Friedline S, Harrison DE, Hejtmancik JF, Nadon N, Strong R, Wood LK, Woodward MA, Miller RA. Rapamycin Slows Aging in Mice. Aging Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Delgoffe GM, Powell JD. Exploring functional in vivo consequences of the selective genetic ablation of mTOR signaling in T helper lymphocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;821:317–327. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-430-8_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Araki K, Turner AP, Shaffer VO, Gangappa S, Keller SA, Bachmann MF, Larsen CP, Ahmed R. mTOR regulates memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;460(7251):108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mannick JB, Del Giudice G, Lattanzi M, Valiante NM, Praestgaard J, Huang B, Lonetto MA, Maecker HT, Kovarik J, Carson S, Glass DJ, Klickstein LB. mTOR inhibition improves immune function in the elderly. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(268):268ra179. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lamming DW, Ye L, Sabatini DM, Baur JA. Rapalogs and mTOR inhibitors as anti-aging therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(3):980–989. doi: 10.1172/JCI64099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu Y, Diaz V, Fernandez E, Strong R, Ye L, Baur JA, Lamming DW, Richardson A, Salmon AB. Rapamycininduced metabolic defects are reversible in both lean and obese mice. Aging. 2014;6(9):742–754. doi: 10.18632/aging.100688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]