Abstract

The results of a combination of 6Li and 13C NMR spectroscopic and computational studies of oxazolidinone-based lithium enolates—Evans enolates—in tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution revealed a mixture of dimers, tetramers, and oligomers (possibly ladders). The distribution depended on the structure of the oxazolidinone auxiliary, substituent on the enolate, and THF concentration (in THF/toluene mixtures). The unsolvated tetrameric form contained a D2d-symmetric core structure, whereas the dimers were determined experimentally and computationally to be trisolvates with several isomeric forms.

TOC image

Introduction

A seminal paper by Evans, Bartroli, and Shih in 1981 introduced oxazolidinone-based chiral auxiliaries (eq 1)1 in which boron-based enolates offered spectacular selectivities for aldol additions central to the synthesis of polyketides. Although aldol additions via analogous lithium enolates were notably unselective, Evans and coworkers soon revealed their importance in highly selective alkylations.2 What followed is now history: oxazolidinone-based chiral enolates—so-called Evans enolates—have appeared in more than 1600 patents and countless academic and industrial syntheses.3 Variations of the auxiliaries4 and extensions of oxazolidinones beyond the chemistry of enolates5 attest to their importance.

|

(1) |

Despite rapid and broad developments of Evans enolates in synthesis, structural and mechanistic studies of these compounds remain conspicuously rare.6,7 Presumably the absence of crystal structures stems from limiting physical properties rather than a lack of interest; we have joined the ranks of those who have failed to grow diffractable crystals. Spectroscopic determination of the structures of enolates in solution is inherently difficult owing to the absence of usable O–M scalar coupling, and we have found only a single spectroscopic study of a boron-based Evans enolate.6a,6b The paucity of computational studies is most vexing,6 but computations of the lithium enolates unsupported by experimental data would be of limited value regardless.8,9

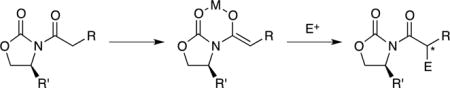

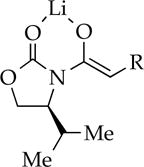

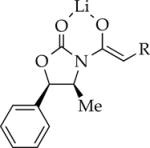

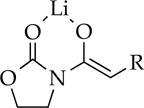

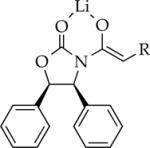

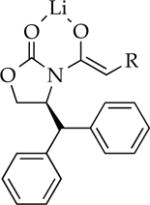

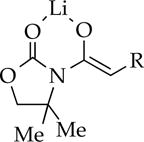

We describe herein NMR spectroscopic and computational studies of a number of oxazolidinone-derived lithium enolates. The general structural types are illustrated in Scheme 1. The auxiliary- and solvent-dependent structural assignments are summarized in Table 1, and limited data on an additional 28 enolates are archived in the supporting information. We focus on the propionate enolate 5 (see Table 1) derived from phenylalanine owing to its importance in synthesis3,4a, and structural tractability. In a subsequent paper we will offer insights into why aldol additions based on lithiated Evans enolates are so challenging1,10,11,12 while possibly nudging them out of relative obscurity.

Scheme 1.

Table 1.

Structures of oxazolidine-derived enolates (0.10 M) in tetrahydrofuran (THF)/toluene and THF solutions at −80 °C corresponding to tetramers (1) and dimers (2 and 3).

| enolate | R | cmpd | 0.20 M THF | neat THF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Me | 5 | tetramer | dimer/tetramer |

| Et | 6 | tetramer | dimer/tetramer | |

| t-Bu | 7 | dimer | dimer | |

| Bn | 8 | dimer | dimer | |

| Ph | 9 | oligomers | oligomers | |

|

Me | 10 | oligomers | dimer |

| Ph | 11 | oligomers | oligomers | |

|

Bn | 12 | oligomers | dimer |

| Me | 13 | oligomers | oligomers | |

|

Me | 14 | oligomers | oligomers |

|

Me | 15 | dimer | dimer |

|

Me | 16 | dimer | dimer |

|

Bn | 17 | dimer | dimer |

|

t-Bu | 18 | dimer | dimer |

| Me | 19 | oligomers | oligomers |

Results

Structure Determinations

General Strategies

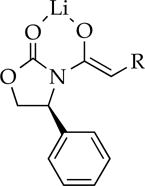

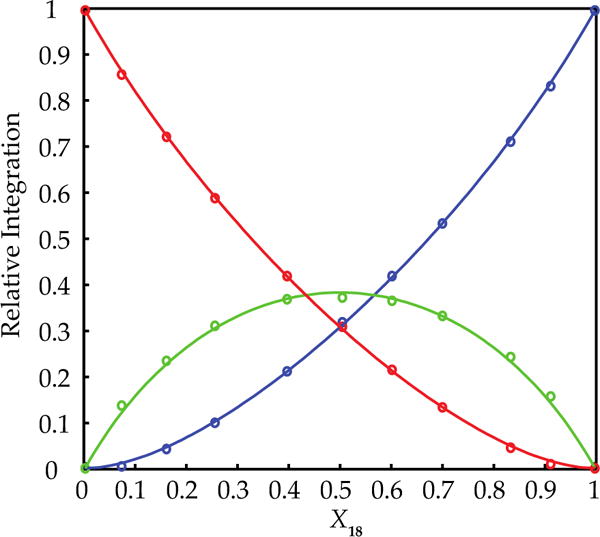

Our structural studies required a variety of tactics and analytical methods, which centered on the method of continuous variations (MCV) delineated in a series of previous papers.13,14 In short, the high symmetry of lithium enolate aggregates is broken by mixing two enolates, generically denoted as An and Bn in eq 2, to afford an ensemble containing heteroaggregates whose numbers, spectral symmetries, and concentration dependencies reveal the aggregation number, n. A plot of the relative concentrations of the aggregates versus measured15 mole fraction of the enolate subunits (X) affords Job plots14,16 (see Figure 2, for example) that confirm the aggregation number. If two homoaggregates coexist (dimers and tetramers, for example), assigning one with MCV allows us to assign the other by monitoring their proportions versus the total enolate titer.

| (2) |

Figure 2.

Job plot of dimeric 7 and 18 at fixed (0.10 M) total enolate concentration in neat THF at −80 °C. The relative integrations are plotted as a function of the mole fraction of 18.

Solvation numbers were probed by using several methods. Pyridine is a 6Li chemical shift reagent: solvated 6Li nuclei shift markedly (0.5–1.5 ppm)17 downfield, whereas unsolvated nuclei do not shift detectably. The relative tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvation numbers can be quantitated by monitoring the homoaggregate dimer–tetramer proportions versus THF concentration (with a hydrocarbon cosolvent). When guided by detailed experimental data, density functional theory (DFT) computations18 offer particularly compelling insights. A few computational results are salted throughout the text; extensive computations are archived in the supporting information. A summary of the auxiliary- and condition-dependent results is found in Table 1.

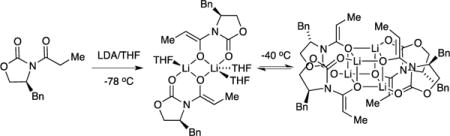

Enolization

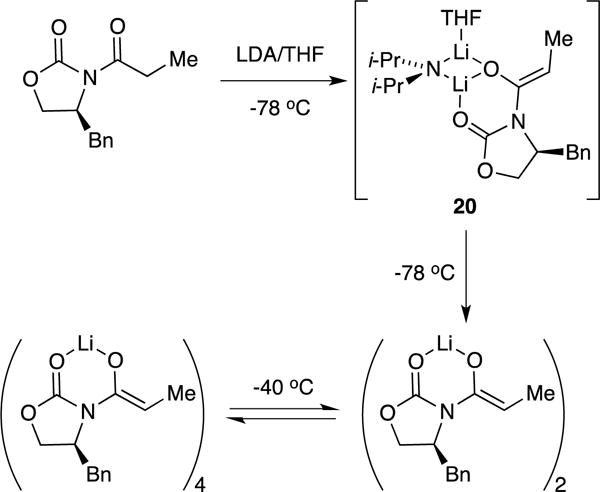

The enolates were generated using [6Li] lithium diisopropylamide ([6Li]LDA) or [6Li,15N]LDA19 in THF as illustrated in Scheme 2. At −80 °C the enolization proceeds through mixed dimer 20 (d, JLi–N = 5.2 Hz).20 The single resonance indicates that the chelate in 20 is either nonexistent or the exchange is fast on NMR time scales. Broadening at lower temperatures suggested the latter. The enolization can be completed by either holding the temperature at −78 °C or warming to −40 °C. The results are not the same, however. Enolization at −78 °C affords exclusively dimer as the kinetic product, which is stable for hours. Warming to −40 °C equilibrates the homoaggregates, affording distributions of dimers and tetramers that are sensitive to enolate and THF concentrations. We focus exclusively on equilibrated mixtures in this report and reserve discussion of unequilibrated mixtures21 for a subsequent treatise on the aldol addition.

Scheme 2.

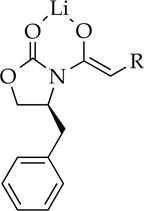

Solvated Dimers

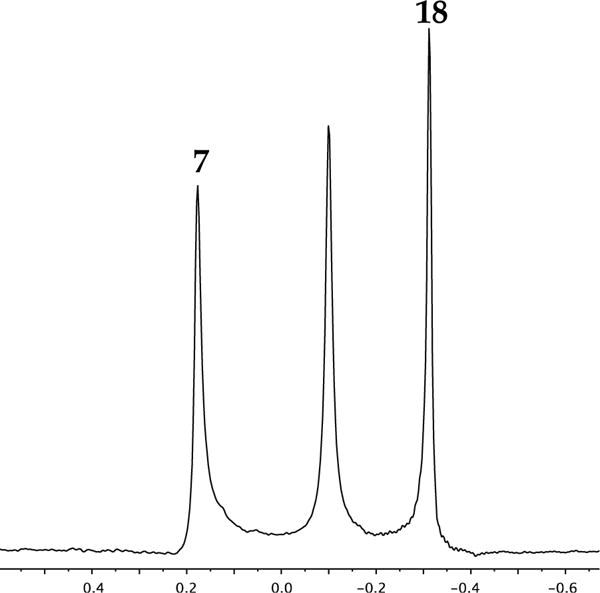

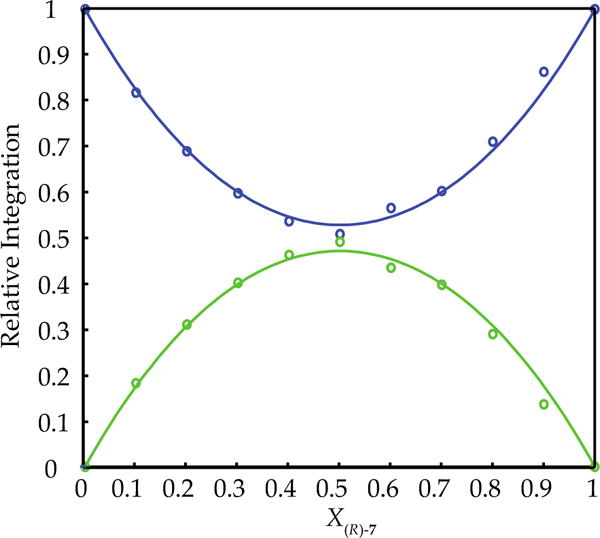

Neat THF solutions of hindered enolates 7 and 18 at −80 °C each display a single 6Li resonance. Both also show marked (>0.6 ppm) downfield shifts with the addition of pyridine, which attests to the importance of solvation analyzed quantitatively below.17,22 The 6Li resonances of 7 and 18 are sufficiently well-resolved for the use of MCV (Figure 1). Thus, varying the proportions in mixtures of 7 and 18 at a constant total enolate titer revealed a single heteroaggregate consistent with enolate dimers. Plotting the relative integration versus the measured mole fraction of enolate subunit 18 (XB) afforded a Job plot (Figure 2) consistent with a nearly statistical A2–AB–B2 mixture of homo- and heterodimers (see Table 1). An alternative approach that we originally applied to hexameric β-amino ester enolates13a involves varying the mole fraction (optical purity) of two enantiomers (eq 3). The resulting Job plot obtained with R/S mixtures of 7 (Figure 3) was a bit unusual in showing only two curves because the homochiral dimers [(R)–7]2 and [(S)–7]2 (A2 and B2, respectively) were indistinguishable. In a perfectly statistical (1:2:1) distribution, the two curves in Figure 3 would intersect at a relative aggregate concentration of 0.50 (y axis) and X = 0.50 (x axis).

| (3) |

Figure 1.

Equimolar mixture of dimeric 7 and 18 (0.10 total enolate concentration) in neat tetrahydrofuran (THF) at −80 °C showing a single heterodimer resonance.

Figure 3.

Job plot of (S)-7 and (R)-7 dimers (0.10 M total enolate concentration) in neat THF at −80 °C. The relative integrations of the homoaggregates and the heteroaggregate are plotted as a function of the mole fraction of (R)-7.

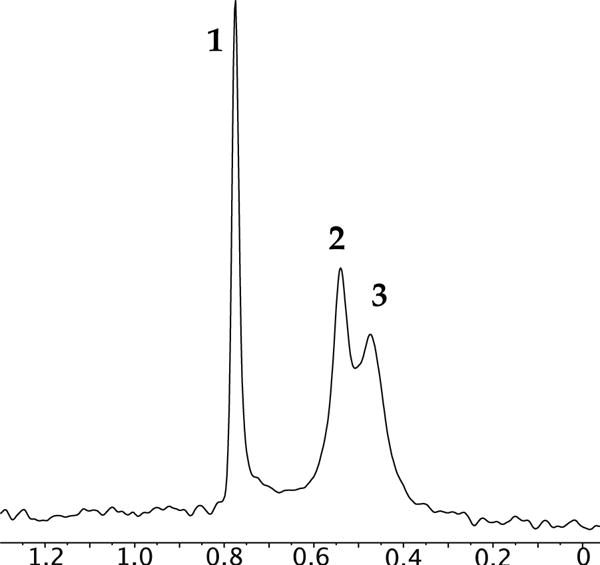

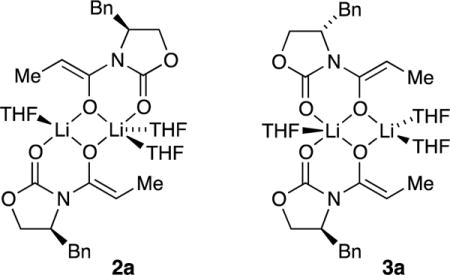

We occasionally obtained glimpses of spectral complexity consistent with coexisting symmetric and unsymmetric dimers and tentatively assigned them as 2 and 3, respectively. The 6Li resonance attributed to dimers was often broad, decoalescing at temperatures below −80 °C to give two dimer-derived resonances (Figure 4) and occasionally as many as three in especially hindered cases such as 7. The intensities of the various dimer resonances are independent of enolate and solvent concentration, attesting to the common aggregation and solvation numbers. Two resonances manifested a 1:1 integration, which suggested a single unsymmetric dimer consistent with (but by no means definitively supporting) structure 3. Facile coalescences of the putative dimer resonances but not the tetramer resonance between −80 and −95 °C were consistent with isomer exchanges. In general, however, dimer isomerism eluded detailed experimental scrutiny; all we know for certain is that symmetric and unsymmetric variants are observable in some samples.23,24

Figure 4.

6Li NMR spectrum of 5 (0.10 M total concentration) in neat THF at −80 °C showing equilibrium populations of tetramer 1 and isomeric dimers 2 and 3.

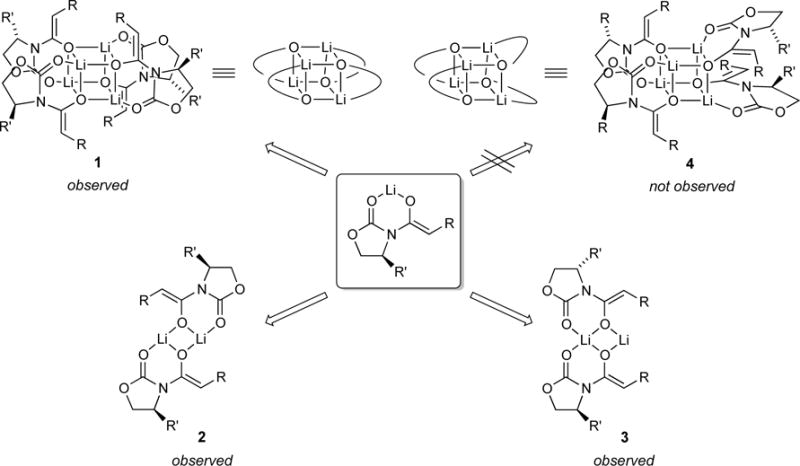

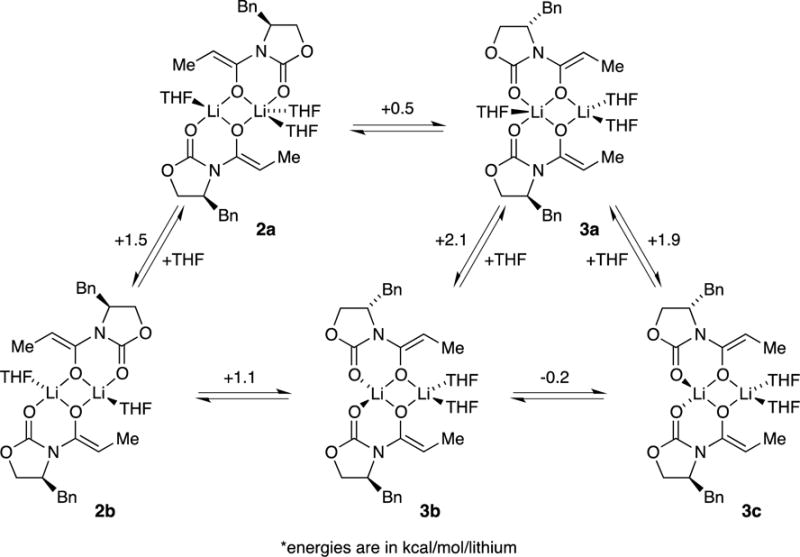

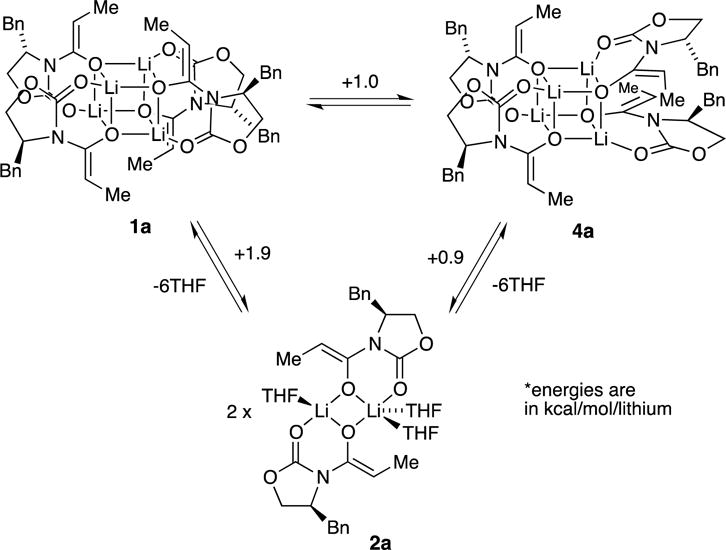

Computational studies at the B3LYP level of theory with the 6–31G(d) basis set and MP2 correction offered some insights.8 The reported energies are free energies at −78 °C and do not account for translational entropy (Scheme 3).25 Symmetric dimer 2a derived from enolate 5 displayed favorable solvation up to the trisolvate, consistent with experiment. No tetrasolvates were found. Several spatial orientations (puckering) of 2 were detected; 2a is the most favorable. Similar tendencies toward trisolvation were observed for spirocycle 3a relative to the disolvated forms. Although the trisolvated spirocyclic 3a displayed no stereoisomerism, the disolvated spirocyclic dimer can exist as energetically equivalent stereoisomers 3b and 3c. In general, dimers are promoted by high steric demands and high THF concentration. They are the sole observable form for only a handful of substrates, with valine-derived propionate 10 being the most notable.

Scheme 3.

Dimer–Tetramer Mixtures

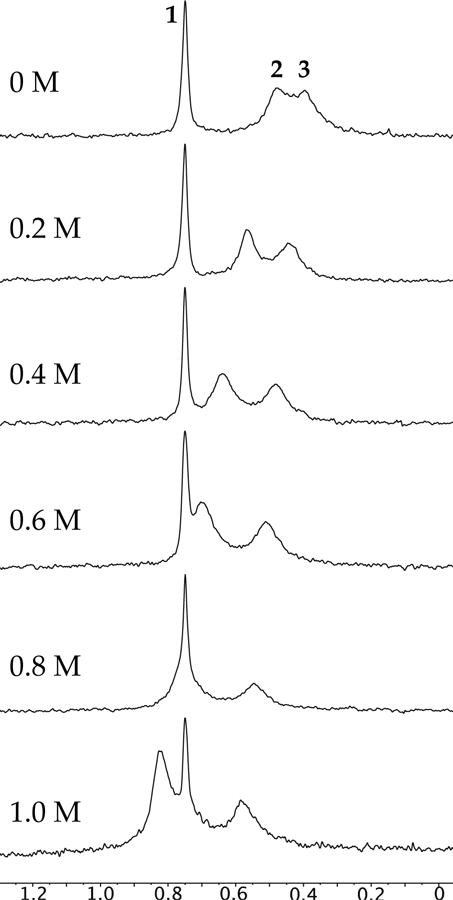

Enolate 5 forms a mixture of dimers 2 and 3 and unsolvated tetramer 1 with a D2d-symmetric core. Raising the enolate concentration or reducing the THF concentration (toluene cosolvent) favored tetramer 1, with the tetramer becoming the exclusive form at concentrations of <3.0 M THF (see Figure 4). The concentration dependencies attest to the higher aggregation state and lower per-lithium solvation number of the tetramer relative to the dimer. Adding low concentrations of pyridine causes a marked shift of only the dimer-derived resonances (Figure 5), which shows that the tetramer is unsolvated. The merits of pyridine as a shift reagent and diagnostic probe of solvation are considerable.

Figure 5.

6Li spectra of 5 (0.10 M) with various pyridine concentrations (as labeled) in neat THF at −80 °C.

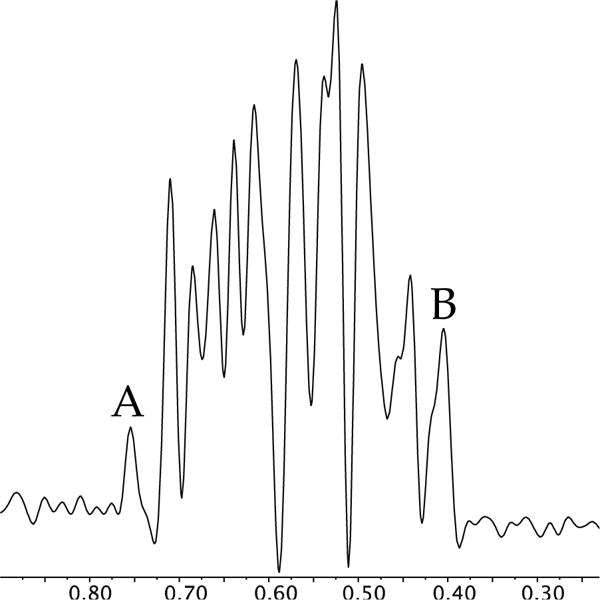

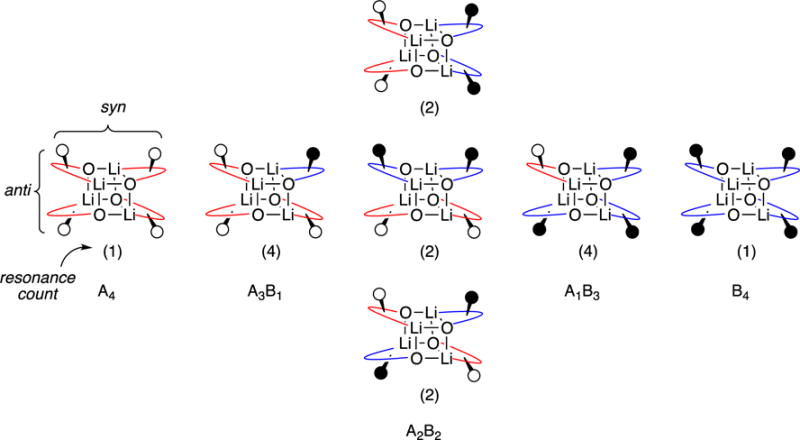

Empirical studies of dozens of pairs of enolates in which we probed for adequate resolution of the complex tetramer ensemble led us to pairings of the substitutionally similar propionyl-derived enolate 5 and butyryl-derived enolate 6. The ensembles generated from these mixtures were extraordinarily complex (Figure 6). Traces of pyridine were added to shift the dimer resonances downfield of the ensemble. The resonance count of 16 within the ensemble matched that predicted for tetramers assuming slow chelate exchange within tetramers bearing a D2d-symmetric core (Chart 1). By contrast, the corresponding S4 tetramers would produce 32 resonances in total. (We return to the distinction of S4 and D2d below.) No amount of tinkering provided sufficient resolution to produce a convincing Job plot, however.

Figure 6.

Equimolar mixture of tetramers derived from enolates 5 and 6 (0.050 M 5, 0.050 M 6) with 0.20 M THF and 1.0 M pyridine in toluene at −60 °C. A and B correspond to the homotetramers of 5 and 6, respectively.

Chart 1.

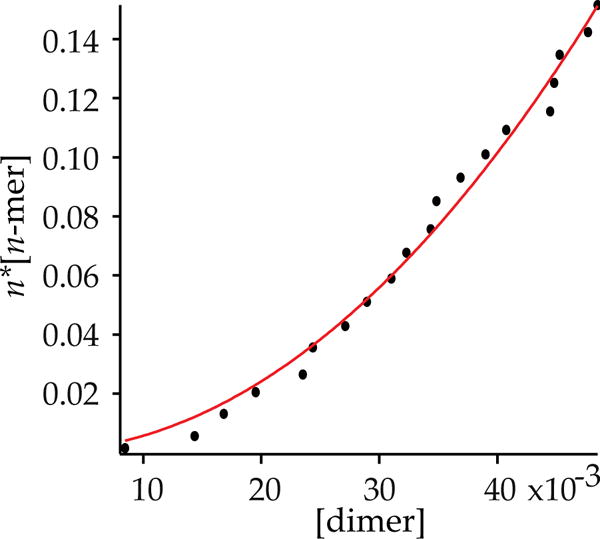

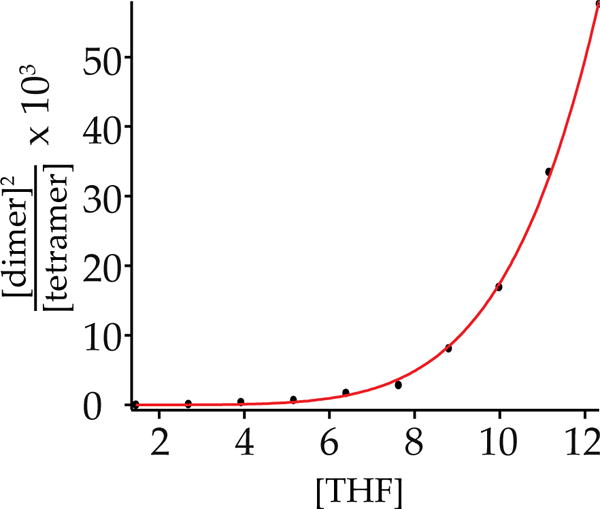

We turned to more traditional strategies to assign the higher aggregate (n-mer) as a tetramer. A plot of the relative concentration of enolate dimer and n-mer versus total concentration (eqs 4 and 5 and Figure 7) afforded an aggregation number of n = 4.1 ± 0.1, consistent with a tetramer. Moreover, given that the tetramer was unsolvated, a plot of dimer–tetramer proportion versus THF concentration (eqs 6 and 7 and Figure 8) afforded a solvation number of 3 (m = 2.86 ± 0.04) for the dimer.24 Computations support the trisolvation assignment (vide infra).

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Figure 7.

Plot of concentration of dimeric 5 versus enolate normality to determine the tetramer aggregation state in neat THF at −60 °C. The curve corresponds to a best fit of y = n*Keq1/2(xn/2), such that y = n*[n-mer], x = [dimer], and n = aggregation number of the n-mer. The fit shows that n is 4.1 ± 0.2.

Figure 8.

Fit of aggregate concentration versus THF concentration for enolate 5 at −60 °C. The curve corresponds to a best fit of eq 7 (m = 2.86 ± 0.04).

Tetramers 1 and 4 can be distinguished spectroscopically in that chiral chelates of 1 display a single 6Li resonance and a single set of 1H and 13C resonances, whereas tetramer 4 with an S4-symmetric core should show duplication of all resonances.13b At −100 °C we saw neither duplication nor even hints of broadening, which provided strong, albeit indirect, evidence of 1.

Computationally, we detected a modest preference for the D2d tetramer (1a) relative to the experimentally unobserved S4 isomer (4a; see Scheme 4). Although comparisons of dimers and tetramers are dubious (non-isodesmic),26 we note that the computations showed that the deaggregation is nearly thermoneutral (without accounting for translational entropy affiliated with solvation25).

Scheme 4.

Monomers

Monomers have not been observed in THF solution. Computations show that the deaggregation of disolvated dimers to give trisolvated monomers costs 1.7 kcal/mol/lithium. As an aside, the most hindered substrates, such as 7 and 18 (see Table 1), afford monomers with added N,N,N′,N′–tetramethylcyclohexanediamine, a chelating diamine with a high capacity to deaggregate organolithium aggregates.20

Discussion

The lithiation of acylated oxazolidinones is fast relative to the rates at which the resulting lithium enolate aggregates equilibrate (see Scheme 2). Although evidence is mounting that aging effects are consequential to reactivity,9b,21 such aggregate dynamics are not the topic of this paper. All assignments stem from fully equilibrated mixtures of homoaggregates obtained using the combination of tactics outlined at the beginning of the results section. The use of MCV (Job plots) is only a portion of the strategy, but it is the lynchpin for providing clear assignments for the dimers. Monitoring the THF- and enolate-concentration-dependent equilibria provided the additional data needed to finish assigning the aggregation and solvation states, with computational chemistry adding some nuance. In summary, lithiated Evans enolates can reside as exclusively dimers, dimer–tetramer mixtures, exclusively tetramers, or even mixtures of oligomers (possibly ladders of variable lengths27) depending on the choice of auxiliary, enolate substituent, and THF concentration (see Scheme 1 and Table 1).

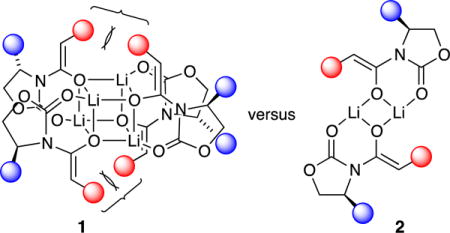

Dimers

Deaggregation is driven by several forces. High steric demands can destabilize higher aggregates, as illustrated below with color-coded depictions of tetramer 1 and dimer 2. Thus, exceedingly hindered enolates bearing substituted oxazolidinones and tert-butyl groups on the enolate moieties afford exclusively dimers. Although the dominant dimeric forms are symmetric dimer 2, we observed fleeting glimpses of less symmetric, demonstrably isomeric (equivalently solvated and aggregated) forms suggested by computational studies to be spirocyclic dimer 3.

|

Dimers are also stabilized relative to tetramers by solvation. Incremental additions of pyridine—a form of NMR shift reagent that markedly shifts solvated 6Li nuclei downfield17—qualitatively confirmed the presence of ligated solvents on the dimers (see Figure 5). Quantifying the dimer–tetramer ratio benchmarked to unsolvated tetramers showed that 2a and 3a are trisolvated. DFT computations concurred (see Scheme 3).

|

Tetramers

Intermediate steric demands—steric demands akin to the standard propionate-based Evans enolate 5 used in synthesis—and reduced THF concentrations promote tetramer formation. Although the ensembles used to assign tetramers with MCV (see Figure 6) showed a peak count (see Chart 1) consistent with tetramers bearing D2d-symmetric cubic cores (1), the resolution thwarted Job plot analysis. Nonetheless, quantitation of the dimer–tetramer equilibrium confirmed the tetramer aggregation state, and the use of pyridine as a shift reagent confirmed that the tetramers are unsolvated (see Figure 5).

The two tetrameric forms, 1 and 4, bearing D2d and S4 core symmetries (respectively) are both precedented in the crystallographic literature of chelated lithium salts.28,29 Even knowing the enolates were tetrameric, it would have been difficult to predict the stereochemistry. The 6Li and 13C resonance counts for the homotetrameric aggregates as well as within the ensemble of heterotetramers (see Figure 6), however, strongly support the D2d form (1). Although absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence, we are satisfied with the assignment. Moreover, the DFT computations in Scheme 4 support the D2d tetramer, albeit by a narrow margin.

Bolstered by casual inspection of reported crystal structures of chelating lithium salts showing both S4 and D2d forms,28,29 we suspect that steric congestion promotes the S4 forms. We explored this putative preference for 1 computationally by focusing on a variety of unsubstituted and substituted oxazolidinones and found that all prefer the D2d tetramer 1 over the S4 tetramer 4 but without any obvious sterically determined trends. Thus, the oxazolidinone substituent does not appear to be a strong determinant of the tetramer stereochemistry. The oxazolidinone substituents do, however, seem to be important in precluding oligomerization.

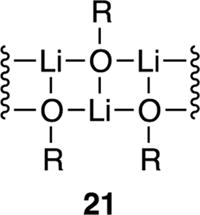

Oligomers

Low steric demands exemplified by unsubstituted oxazolidinones (see Table 1, 10–14) afford intractable broad mounds in the 6Li NMR spectra irrespective of temperature. Additional examples are described in the supporting information. We suspect that some minimum level of substitution is required to preclude laddering (21). The popular valine-derived propionate enolate 10 (see Table 1) sits on the cusp: it is dimeric in neat THF solution 10 but oligomeric at low THF concentrations. A delicate balance appears to be required to differentiate tetramers and oligomers.

|

Conclusions

Organolithium chemists have enjoyed the huge advantages offered by 6Li-X scalar coupling (X = 13C and 15N) for characterizing complex aggregates. There are, however, a host of organolithium salts and other organometallic aggregates for which no such scalar coupling can be observed. The results herein underscore the importance of some of the tricks we can use—MCV, concentration dependencies, pyridine as a chemical shift reagent, and computations—to study the solution structures of lithium enolates. We are optimistic that these strategies will continue to evolve.9

Characterization of the iconic Evans enolates is also a key to understanding the structure–reactivity relationships of synthetically important enolates. The various enolate aggregates described herein have likely been impacting yields and selectivities even without the full appreciation of their consequences by practitioners. The epic struggle by Singer et al.12a at Pfizer to develop a plant-scale aldol addition featured a lithiated Evans enolate. This story is remarkable given the paucity of lithium-based aldol condensations with Evans enolates.11,12

One topic mentioned only in passing is that warming is required for full equilibration of homoaggregated Evans enolates. Slow aggregate exchange in enolates has been noted previously,21 most notably in seminal studies of enolates at very low temperature by Reich.9b,f One could imagine, therefore, that exceedingly fast reactions such as aldol additions might be very different under non-equilibrium and equilibrium conditions. By contrast, slow reactions such as alkylations2,3 may be impervious to the observable forms, simply funneling through whatever fleeting form offers the route of least resistance to product. We have little doubt that a multitude of mechanisms exist for the various reactions of Evans enolates. Of course, we are merely foreshadowing forthcoming mechanistic studies already in progress.

Experimental

Reagents and Solvents

THF and toluene were distilled from solutions containing sodium benzophenone ketyl. The toluene stills contained approximately 1% tetraglyme to dissolve the ketyl. LDA, [6Li]LDA, and [6Li,15N]LDA were prepared as described previously.19 Solutions of LDA were titrated for active base by using a literature method.30 Air- and moisture-sensitive materials were manipulated under argon using standard glove box, vacuum line, and syringe techniques. The Evans enolate precursors were either purchased or prepared as described previously.4 Several previously unreported precursors were prepared by acylating1 the oxazolidinones, which were prepared from the amino alcohol and diethylcarbonate31 as described in the supporting information.

NMR Spectroscopy

Individual stock solutions of substrates and LDA were prepared at room temperature. An NMR tube under vacuum was flame-dried on a Schlenk line and allowed to return to room temperature. It was then backfilled with argon and placed in a −78 °C dry ice/acetone bath. The appropriate amounts of oxazolidinone and LDA (1.1 equiv) were added sequentially via syringe. The tube was sealed under partial vacuum, vortexed three times on a vortex mixer for 5 s with cooling between each vortexing, and stored in a freezer at −20 °C. Samples were stored for days at −86 °C. Each sample routinely contained 0.10 M total enolate with a 0.005 M excess of LDA. (The excess base forms mixed dimers 20 with the resulting enolates, which were characterized with 6Li and 15N NMR spectroscopy.) Standard 6Li and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a 500 MHz spectrometer at 73.57 and 125.79 MHz, respectively. The 6Li and 13C resonances are referenced to 0.30 M [6Li]LiCl/MeOH at −90 °C (0.0 ppm) and the CH2O resonance of THF at −90 °C (67.57 ppm).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM077167) for support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Spectra, additional Job plots, and authors for reference 18. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References and Footnotes

- 1.Evans DA, Bartroli J, Shih TL. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2127. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans DA, Ennis MD, Mathre DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:1737. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Ager DJ, Prakash I, Schaad DR. Chem Rev. 1996;96:835. doi: 10.1021/cr9500038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu G, Huang M. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2596. doi: 10.1021/cr040694k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Farina V, Reeves JT, Senanayake CH, Song JJ. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2734. doi: 10.1021/cr040700c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Evans DA, Shaw JT. Ĺactualité Chimique. 2003:35. [Google Scholar]; (e) Lin G-Q, Li Y-M, Chan ASC. Principles and Applications of Asymmetric Synthesis. Wiley & Sons; New York: 2001. p. 135. [Google Scholar]; (f) Palomo C, Oiarbide M, Garcia JM. Chem Soc Rev. 2004;33:65. doi: 10.1039/b202901d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Franklin AS, Paterson I. Contemp Org Syn. 1994;1:317. [Google Scholar]; (h) Baiget J, Cosp A, Galvez E, Gomez-Pinal L, Romea P, Urpi F. Tetrahedron. 2008:5637. [Google Scholar]; (i) Velazques F, Olivio H. Curr Org Chem. 2002;6:303. [Google Scholar]; (j) Mahrwald R, editor. Modern Aldol Reactions, Vols 1 and 2. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oxazolidinone precursors to enolates 5–19 in Table 1 were prepared according to literature procedures: 5 and 13; Mabe PJ, Zakarian A. Org Lett. 2014;16:516. doi: 10.1021/ol403398u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kretschmer M, Dieckmann M, Li P, Rudolph S, Herkommer D, Troendlin J, Menche D. Chem Euro J. 2013;19:15993. doi: 10.1002/chem.201302197. 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Neumann CS, Walsh CT. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14022. doi: 10.1021/ja8064667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wulischleger CW, Gertsch J, Altmann K. Org Lett. 2010;12:1120. doi: 10.1021/ol100123p. 7 and 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Evans DA, Britton TC, Dorow RL, Dellaria JF. Tetrahedron. 1988;44:5525. [Google Scholar]; Satoh M, Aramaki H, Nakamura H, Inoue M, Kawakami H, Shinkai H, Matsuzaki Y, Yamataka K. US2006/84665. U S Patent. 2006;A1 8.; Szostak M, Spain M, Eberhart AJ, Procter DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;36:2268. doi: 10.1021/ja412578t. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lai P, Dubland JA, Sarwar MG, Chudzinski MG, Taylor MS. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:7586. 10. [Google Scholar]; Gille A, Hiersemann M. Org Lett. 2010;12:5258. doi: 10.1021/ol1023008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bull SD, Davies SG, Jones S, Sanganee HJ. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1999;4:387. 11. [Google Scholar]; Matsumura Y, Kanda Y, Shirai K, Onomura O, Maki T. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:7411. [Google Scholar]; Gore MP, Vederas JC. J Org Chem. 1986;51:3700. 12. [Google Scholar]; Evans DA, Mathre DJ, Scott WL. J Org Chem. 1985;50:1830. 14. [Google Scholar]; Huang L, Wulff WD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8892. doi: 10.1021/ja203754p. 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Shin D, Jung J, Seo S, Lee Y, Paek S, Chung YK, Shin DM, Suh Y. Org Lett. 2003;5:3635. doi: 10.1021/ol035289e. 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Perry MA, Trinidad JV, Rychnovsky SD. Org Lett. 2013;15:472. doi: 10.1021/ol303239t. 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Matousek V, Togni A, Bizet V, Cahard D. Org Lett. 2011;13:5762. doi: 10.1021/ol2023328. 18 and 19: see supporting information. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Evans DA, Chapman KT, Hung DT, Kawaguchi AT. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1987;26:1184. [Google Scholar]; (b) Flynn BL, Manchala N, Krenske EH. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9156. doi: 10.1021/ja4036434. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mamai A, Madalengoitia JS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:9009. [Google Scholar]; (d) Also see ref 3a.

- 6.(a) Shinasha CB, Sunoj RB. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12319. doi: 10.1021/ja101913k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sreenithya A, Sunoj RB. Org Lett. 2012;14:5752. doi: 10.1021/ol302761n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shinisha CB, Sunoj RB. Org Lett. 2010;12:2868. doi: 10.1021/ol100969f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Goodman JM, Paton RS. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 2007:2124. doi: 10.1039/b704786j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Baringhaus KH, Matter H, Kurz M. J Org Chem. 2000;65:5031. doi: 10.1021/jo0001885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimball DB, Michalczyk R, Moody E, Ollivault-Shiflett M, De Jesus K, Silks LA., III J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14666. doi: 10.1021/ja036414k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For leading references to theoretical studies of O-lithiated species, see:; (a) Khartabi HK, Gros PC, Fort Y, Ruiz-Lopez MF. J Org Chem. 2006;73:9393. doi: 10.1021/jo8019434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Streitwieser A. J Mol Model. 2006;12:673. doi: 10.1007/s00894-005-0045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pratt LM, Streitwieser A. J Org Chem. 2003;68:2830. doi: 10.1021/jo026902v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pratt LM, Nguyen SC, Thanh BT. J Org Chem. 2008;73:6086. doi: 10.1021/jo800528y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Seebach D. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1988;27:1624. [Google Scholar]; (b) Reich HJ. Chem Rev. 2013;113:7130. doi: 10.1021/cr400187u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Braun M. Helv Chim Acta. 2015;98:1. [Google Scholar]; (d) Setzer WN, Schleyer PvR. Adv Organomet Chem. 1985;24:353. [Google Scholar]; (e) Williard PG. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 1. Pergamon; New York: 1991. Chapter 1.1. [Google Scholar]; (f) Reich HJ. J Org Chem. 2012;77:5471. doi: 10.1021/jo3005155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Kim YJ, Streitwieser A. Org Lett. 2002;4:573. doi: 10.1021/ol017175d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Jackman LM, Lange BC. Tetrahedron. 1977;33:2737. [Google Scholar]; (i) Li D, Keresztes I, Hopson R, Williard PG. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:270. doi: 10.1021/ar800127e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Zune C, Jerome R. Prog Polymer Sci. 1999;24:631. [Google Scholar]; (k) Baskaran D. Prog Polym Sci. 2003;28:521. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lithiated Evans enolates have been reported to undergo addition to aldehydes (ref 11) and ketones (ref 12), with yields and selectivities spanning a wide range.

- 11.(a) Sobahi TR. Oriental J Chem. 2004;20:17. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bonner MP, Thornton ER. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:1299. [Google Scholar]; (c) Pridgen LN, Abdel-Magid AF, Lantos I, Shilcrat S, Eggleston DS. J Org Chem. 1993;58:5107. [Google Scholar]; (d) Abdel-Magid A, Pridgen LN, Eggleston DS, Lantos I. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:4595. [Google Scholar]; (e) Pridgen LN, Abdel-Magid A, Lantos I. Tett Lett. 1989;30:5539. [Google Scholar]; (f) Banks MR, Blake AJ, Cadogan JIG, Dawson IM, Gaur S, Gosney I, Gould RO, Grant KJ, Hodgson PKG. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1993:1146. [Google Scholar]; (g) Xue C, Voss ME, Nelson DJ, Duan JJW, Cherney RJ, Jacobson IC, He X, Roderick J, Chen L, Corbett RL, Wang L, Meyer DT, Kennedy K, DeGrado WF, Hardman KD, Teleha CA, Jaffee BD, Liu R, Copeland RA, Covington MB, Christ DD, Trzaskos JM, Newton RC, Magolda RL, Wexler RR, Decicco CP. J Med Chem. 2001;44:2636. doi: 10.1021/jm010127e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Jacobsen IC, Reddy GP. Tetrahdron Lett. 1996;37:8263. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Singer RA, Ragan JA, Bowles P, Chisowa E, Conway BG, Cordi EM, Leeman KR, Letendre LJ, Sieser JE, Sluggett GW, Stanchina CL, Strohmeyer H, Blunt J, Taylor S, Byrne C, Lynch D, Mullane S, O’Sullivan MM, Whelan M. Org Process Res Dev. 2014;18:26. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fürstner A, Bouchez LC, Morency L, Funel J, Liepins V, Porée F, Gilmour R, Laurich D, Beaufils F, Tamiya M. Chem Euro J. 2009;15:3983. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Theurer M, Fischer P, Baro A, Nguyen GS, Kourist R, Bornscheuer U, Laschat S. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:3814. [Google Scholar]; (d) Peters R, Althaus M, Diolez C, Rolland A, Manginot E, Veyrat M. J Org Chem. 2006;71:7583. doi: 10.1021/jo060928v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu W, Sheppeck JE, II, Colby DA, Huang H, Nairn AC, Chamberlin AR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1597. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ojida A, Yamano T, Taya N, Tasaka A. Org Lett. 2002;4:3051. doi: 10.1021/ol0263189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Bartroli J, Turmo E, Belloc J, Forn J. J Org Chem. 1995;60:3000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Liou LR, McNeil AJ, Ramírez A, Toombes GES, Gruver JM, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4859. doi: 10.1021/ja7100642. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bruneau AM, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2885. doi: 10.1021/ja412210d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) De Vries TS, Goswami A, Liou LR, Gruver JM, Jayne E, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13142. doi: 10.1021/ja9047784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renny JS, Tomasevich LL, Tallmadge EH, Collum DB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:11998. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The measured mole fraction—the mole fraction within only the ensemble of interest—rather intended mole fraction of the enolates added to the samples—eliminates the distorting effects of impurities.

- 16.Job P. Ann Chim. 1928;9:113. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Tomasevich LL, Collum DB. J Org Chem. 2013;78:7498. doi: 10.1021/jo401080n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reich HJ, Kulicke KJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:273. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jackman LM, Chen X. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:8681. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jackman LM, Petrei MM, Smith BD. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:3451. [Google Scholar]; (e) Jackman LM, DeBrosse CW. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:4177. [Google Scholar]; (f) Deana RK, Recklinga AM, Chena H, Daweab LN, Schneiderac CM, Kozak CM. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:3504. doi: 10.1039/c2dt32682e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Boyle TJ, Pedrotty DM, Alam TM, Vick SC, Rodriguez MA. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:5133. doi: 10.1021/ic000432a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frisch MJ, et al. GaussianVersion 3.09; revision A.1. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma Y, Hoepker AC, Gupta L, Faggin MF, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15610. doi: 10.1021/ja105855v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Collum DB. Acc Chem Res. 1993;26:227. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lucht BL, Collum DB. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:1035. [Google Scholar]

- 21.For examples of reactions that are fast relative to the rates of aggregate–aggregate exchanges see:; (a) McGarrity JF, Ogle CA. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:1810. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones AC, Sanders AW, Bevan MJ, Reich HJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3492. doi: 10.1021/ja0689334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Thompson A, Corley EG, Huntington MF, Grabowski EJJ, Remenar JF, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:2028. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jones AC, Sanders AW, Sikorski WH, Jansen KL, Reich HJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6060. doi: 10.1021/ja8003528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kolonko KJ, Wherritt DJ, Reich HJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16774. doi: 10.1021/ja207218f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Casy BM, Flowers RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:11492. doi: 10.1021/ja205017e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The 6Li resonances of mixed aggregates such as 20 also shift downfield on addition of pyridine.

- 23.(a) Reich HJ, Goldenberg WS, Gudmundsson BÖ, Sanders AW, Kulicke KJ, Simon K, Guzei IA. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8067. doi: 10.1021/ja010489b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Steiner A, Stalke D. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:1752. [Google Scholar]; (c) Belzner J, Schar D, Dehnert U, Noltemeyer M. Organometallics. 1997;16:285. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jantzi KL, Puckett CL, Guzei IA, Reich HJ. J Org Chem. 2005;70:7520. doi: 10.1021/jo050592+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Vos M, de Kanter FJJ, Schakel M, van Eikema Hommes NJR, Klumpp GW. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2187. [Google Scholar]; (f) Hilmersson G, Davidsson Ö. J Org Chem. 1995;60:7660. [Google Scholar]; (g) Hilmersson G, Arvidsson PI, Davidsson Ö, Håkansson M. Organometallics. 1997;16:3352. [Google Scholar]; (h) Hilmersson G. Chem Eur J. 2000;6:3069. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20000818)6:16<3069::aid-chem3069>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Kahne D, Gut S, DePue R, Mohamadi F, Wanat RA, Collum DB, Clardy J, Van Duyne G. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:4865. [Google Scholar]; (i) Reich HJ, Sikorski WH, Thompson JL, Sanders AW, Jones AC. Org Lett. 2006;8:4003. doi: 10.1021/ol061489p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Larranaga O, de Cozar A, Bickelhaupt FM, Zangi R, Cossio FP. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:13761. doi: 10.1002/chem.201301597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The dimer concentrations were determined using integrations obtained at −80 °C wherein stereoisomers were time averaged.

- 25.The computations use the Gaussian standard state of 1.0 atm. If the THF concentration is corrected to neat THF (approximately 12 M), each solvation step benefits from approximately 2.0 kcal/mol of additional stabilization at −78 °C (195 K).; Pratt LM, Merry S, Nguyen SC, Quan P, Thanh BT. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:10821. [Google Scholar]

- 26.From Wikipedia, an isodesmic reaction is a chemical reaction in which the type of chemical bonds broken in the reactant are the same as the type of bonds formed in the reaction product.

- 27.Mulvey RE. Chem Soc Rev. 1991;20:167. See also ref 14c. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Niemeyer J, Kehr G, Frohlich R, Erker G. Dalton Trans. 2009:3731. doi: 10.1039/b822741a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Williard PG, Tata JR, Schlessinger RH, Adams AD, Iwanowicz EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:7901. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jones C, Junk PC, Leary SG, Smithies NA. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 2000:3186. [Google Scholar]; (d) Muller G, Brand J. Z Anorg Allg Chem. 2005;631:2820. [Google Scholar]; (e) Rajeswaran M, Begley WJ, Olson LP, Huo S. Polyhedron. 2007;26:3653. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kathirgamanathan P, Surendrakumar S, Antipan-Lara J, Ravichandran S, Chan YF, Arkley V, Ganeshamurugan S, Kumaraverl M, Paramswara G, Partheepan A, Reddy VR, Bailey D, Blake AJ. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:6104. [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Arnett EM, Nichols MA, McPhail AT. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7059. [Google Scholar]; (b) Graalmann O, Klingebiel U, Clegg W, Haase M, Sheldrick GM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1984;23:891. [Google Scholar]; (c) Williard PG, Salvino JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:3931. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jastrzebski JTBH, van Koten G, Christophersen MJN, Stam CH. J Organomet Chem. 1985;292:319. [Google Scholar]; (e) Strauch J, Warren TH, Erker G, Frohlich R, Saarenketo P. Inorg Chim Acta. 2000;300:810. [Google Scholar]; (f) Driess M, Dona N, Merz K. Chem-Eur J. 2004;10:5971. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Dippel K, Keweloh NK, Jones PG, Klingebiel U, Schmidt D. Z Naturforsch, B: Chem Sci. 1987;42:1253. [Google Scholar]; (h) Davies RP, Wheatley AEH, Rothenberger A. J Organomet Chem. 2006;691:3938. [Google Scholar]; (i) Nichols MA, McPhail AT, Arnett EM. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:6222. [Google Scholar]; (j) Davies JE, Davies RP, Dunbar L, Raithby PR, Russell MG, Snaith R, Warren S, Wheatley AEH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1997;36:2334. [Google Scholar]; (k) Brehon M, Cope EK, Mair FS, Nolan P, O’Brien JE, Pritchard RG, Wilcock DJ. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1997:3421. [Google Scholar]; (l) Schmidt-Base D, Klingebiel U. Chem Ber. 1989;122:815. [Google Scholar]; (m) Armbruster F, Armbruster N, Klingebiel U, Noltemeyer M, Schmatz S. Z Naturforsch, B: Chem Sci. 2006;61:1261. [Google Scholar]; (n) Apeloig Y, Zharov I, Bravo-Zhivotovskii D, Ovchinnikov Y, Struchkov Y. J Organomet Chem. 1995;499:73. [Google Scholar]; (o) Graser M, Kopacka H, Wurst K, Muller T, Bildstein B. Inorg Chim Acta. 2013;401:38. [Google Scholar]; (p) Also, see ref 13.

- 30.Kofron WG, Baclawski LM. J Org Chem. 1976;41:1879. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newman MS, Kutne A. J Am Chem Soc. 1951;73:4199. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.