Abstract

Treatments with bismuth-containing quadruple therapy (QT), sequential therapy (ST), or concomitant therapy (CT) have been proposed as empirical first-line regimens for Helicobacter pylori. We compared the efficacy and tolerability of 10 days bismuth-containing quadruple QT, 10 days ST, and 10 days CT with as first-line treatments for H. pylori in a randomized crossover study. The subjects were randomly divided into three groups. The first 130 patients were treated with rabeprazole, bismuth potassium citrate, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 10 days. The second 130 patients in the sequential group were treated with rabeprazole and amoxicillin for 5 days, and then rabeprazole, clarithromycin, and metronidazole for an additional 5 days. The last 130 patients in the concomitant group were treated with rabeprazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole for 10 days. H. pylori eradication was confirmed by urea breath test at 6 weeks. The primary outcome was eradication rates of first-line treatment by intention to treat and per protocol (PP) analyzes. There was no difference between the average ages and the male/female ratio of the groups. The PP analysis was performed on 121, 119, and 118 patients in the QT, ST, and CT groups, respectively. In the PP analysis, the successful eradication 94.2% (114/121), 95.0% (113/119), and 95.8% (113/118) the QT, ST, and CT groups, respectively. There was no significant difference among the three groups (p = 0.86). 10 days QT, ST, and CT are highly effective as empirical first-line therapies for H. pylori in the region with high clarithromycin resistance.

KEY WORDS: Helicobacter pylori, quadruple therapy, sequential therapy, concomitant therapy

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative bacterium found on the luminal surface of the gastric epithelium. The bacterium induces chronic inflammation of the underlying mucosa and typically infects the stomach in the first few years of life. It was isolated for the first time by Marshall and Warren [1]. It survives in the acidic environment of the gastric mucosa and causes gastritis, peptic ulcers, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric cancer [2]. Therefore, the eradication of H. pylori can markedly lower gastric and duodenal ulcer recurrence and allowing the treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [3]. The first-line choice of treatment for H. pylori infection in the United States and Europe consists of a conventional triple therapy, in which a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), clarithromycin, and amoxicillin are administered for 7-14 days [4-6]. Conventional triple therapy is also recommended as a first-line therapy by Asian-Pacific and Brazilian Consensus Groups [7,8]. However, over the past few years, the efficacy of conventional triple therapy has decreased, with eradication rates of <80%, especially in the region with high clarithromycin resistance, including Turkey [9-12]. Decreased eradication rates are due primarily to increased bacterial resistance to clarithromycin, indicating the need for new first-line treatments.

Instead of conventional triple therapy, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy (QT), concomitant therapy (CT), and sequential therapy (ST) can be used. Bismuth-containing QT, CT, and ST are more effective than conventional triple therapy [5,13-16]. However, the comparison between the eradication rates of these therapies has been controversial, and almost no studies have compared all of these therapies, either. Through this prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial, we compared the eradication rate of bismuth-containing QT, ST, and CT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

From October 2013 to October 2014, this study was undertaken at Siirt State Hospital. The study subjects were patients with gastric symptoms and confirmed gastritis, with gastric and duodenal ulcers on esophagogastroduodenoscopy. The subjects were between 17 and 75 years of age. Women who were pregnant or lactating, patients previously treated with H. pylori eradication therapy, patients who previously underwent gastric surgery, patients with malignant neoplasms, and patients with other severe concomitant diseases were all excluded.

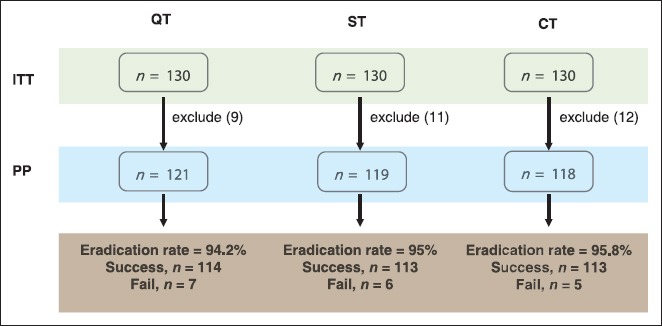

A total of 390 subjects underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy, were biopsied and had diagnosed H. pylori infection confirmed with Giemsa stain. The subjects were randomly divided into three groups using a table of random numbers. The first group was treated with rabeprazole, amoxicillin, tetracycline, and bismuth substrate (the bismuth-containing quadruple group). The second group was treated with rabeprazole and amoxicillin followed by rabeprazole, clarithromycin, and metronidazole (the sequential group). The last group was treated with rabeprazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole (the concomitant group). 6 weeks after the treatment period and at least 2 weeks with no administration of PPIs, we confirmed H. pylori eradication using C13-urea breath tests. To confirm patient compliance, we asked the patients to bring their remaining medication and counted the rest of their pills. Patients with a compliance of <80% were excluded from the study per protocol (PP) analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of study. QT: Quadruple treatment, ST: Sequential treatment, CT: Concomitant treatment, PP: Per protocol, ITT: Intention to treat.

Demographic information, history of smoking, alcohol consumption, previous upper gastrointestinal bleeding and endoscopic findings including, gastritis, erosions, and the presence or absence of bulbar deformity were recorded questionnaires.

H. pylori eradication

The first 130 patients were treated with rabeprazole 80 mg (40 mg/b.i.d), bismuth potassium citrate 440 mg (220 mg/b.i.d), metronidazole 1.5 g (500 mg/t.i.d), and tetracycline 1.5 g (500 mg/t.i.d) for 10 days. The second 130 patients in the sequential group were treated with rabeprazole 80 mg (40 mg/b.i.d) and amoxicillin 2.0 g (1000 mg/b.i.d) for 5 days, then rabeprazole 80 mg (40 mg/b.i.d), clarithromycin 1.0 g (500 mg/b.i.d), and metronidazole 1.5 g (500 mg/t.i.d) for an additional 5 days. The last 130 patients in the concomitant group were treated with rabeprazole 80 mg (40 mg/b.i.d.), amoxicillin 2.0 g (1000 mg/b.i.d), clarithromycin 1.0 g (500 mg/b.i.d), and metronidazole 1.5 g (500 mg/t.i.d) for 10 days. Rabeprazole was taken before the meals; other drugs were taken after the meals.

Compliance and adverse drug reaction

We interviewed patients to investigate compliance and the adverse effects of the drugs, including abdominal bloating, abdominal pain, bitter taste, constipation, dizziness, epigastric pain, general weakness, halitosis, headache, loose stool, loss of appetites, nausea, oral ulcer, skin eruption, sleeping tendency, and vomiting. The term “<80% compliance” was described as termination of the therapy before the 8th day due to adverse drug reaction.

Statistical analysis

The results of this study were analyzed in an intention to treat (ITT) population and a PP population. IBM SPSS software for Windows (version 19.1; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), was used for the statistical analyzes, in which the eradication rate was analyzed by the c2 test. p < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. We compared the eradication rate of the quadruple group and the other two groups using the c2 test, and the three tests were Bonferroni corrected. We presumed that the eradication rate of the CT to be 90% and that the eradication rate of sequential and QT was 90%. To calculate the ITT eradication rates, everyone who entered the study was considered, and to calculate PP eradication rates, only those who completed the entire protocol with more than 80% compliance to treatment were considered. By setting the significance level to p < 0.05, the statistical power to 90% and the drop-out rate to 10%, we calculated a need for 130 patients in each group.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

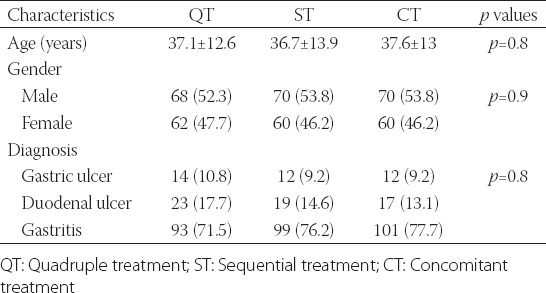

There was no difference (p = 0.8) between the average ages of the groups, which were 37.17 ± 12.6, 36.70 ± 13.9, and 37.61 ± 13.0 in the QT, ST, and CT groups, respectively. The male ratios were 52.3, 53.8, and 53.8 (p = 0.9), respectively. Gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers and gastritis were, respectively, confirmed in 10.8%, 17.7%, and 71.5% of the QT group patients; in 9.2%, 14.6%, and 76.2% of the ST group patients; and in 9.2%, 13.1%, and 77.7% of the CT group patients. There was no significant difference among the three groups (p = 0.82) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients n (%)

Eradication rate for first-line treatment

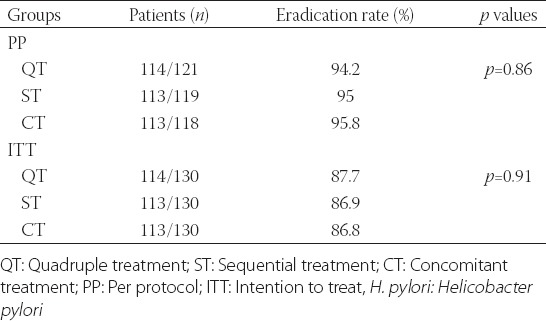

The PP analysis was performed on 121, 119, and 118 patients in the quadruple, sequential, and concomitant groups, respectively. We excluded patients who did not receive a C13-urea breath test (5, 6, and 5 patients, respectively) and patients with less than an 80% compliance level (4, 5, and 7 patients, respectively). In the PP analysis, the successful eradication rate in the QT group was 94.2% (114/121) (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.48 and 0.67), the eradication rate in the ST group was 95.0% (113/119) (95% CI 0.78 and 0.92), and in the CT group was 95.8% (113/118) (95% CI 0.61 and 0.86) of patients experienced successful. There was no significant difference among the three groups (p = 0.86) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Eradication rates of H. pylori

In the ITT analysis, the eradication rates were 87.7% (114/130) (95% CI 0.58 and 0.79), 86.9% (113/130) (95% CI 0.39 and 0.63), and 86.9% (113/130) (95% CI 0.61 and 0.83) in the QT, ST, and CT groups, respectively. There was no significant difference among the three groups (p = 0.91) (Table 2).

Adverse drug reaction

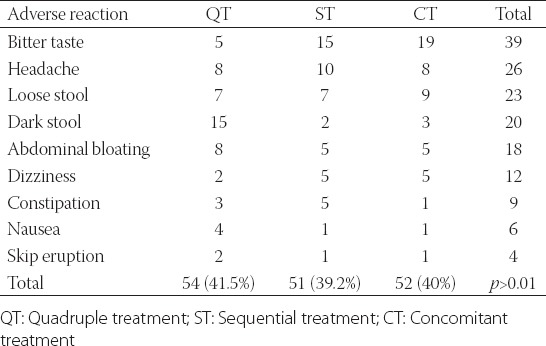

157 of those 390 patients reported minor adverse drug reactions. The percentages of patients with adverse reactions were 41.5% in the QT group (54/130), 39.2% in the ST group (51/130), and 40% in the CT group (52/130) (p > 0.05).

In order of frequency, bitter taste, loose stool, headache, dark stool, and abdominal bloating were the most common adverse reactions in all study group. Dark stool, abdominal bloating, and headache were the most common adverse reactions in the QT group. Bitter taste, headache, and loose stool were the most common events in the sequential group and in the ST group. Bitter taste, loose stool, and headache were the most common adverse reactions in the CT group. However, these developments were not statistically significant, and there were no major adverse reactions (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Incidence of adverse drug reactions (n)

DISCUSSION

In regions with high clarithromycin resistance (higher than 20%), QT should be recommended as a first-line therapy if bismuth is available in that particular area [5]. As previously mentioned, the use of standard triple therapy is not satisfactory for achieving a low eradication rate, although the efficacy of this therapy has been improved with the addition of bismuth. Xu et al. reported that 7 days of standard triple therapy plus bismuth increased the eradication rate from 66.67% to 82.09% according to ITT analysis [17]. When the treatment was extended to 14 days, the ITT eradication rate reached 93.7% compared with 80.0% after 7 days of treatment, which suggested that the addition of bismuth can overcome H. pylori resistance to clarithromycin [18]. In addition, in this study, the eradication rate of bismuth-containing QT for 10 days was 94.2% in Turkey where a high frequency of metronidazole and clarithromycin resistance has been observed [19,20]. Many prospective studies were recently performed, and all of these regimens seem to be highly effective in the eradication of H. pylori [11,17,18,21-24].

Although, QT is a highly effective regimen that could be recommended as a first-line therapy, bismuth is not available in many developed countries due to its potential nephrotoxicity [25-27]. However, the results of a meta-analysis that included 35 randomized controlled trials involving 4763 patients detected no statistically significant difference in the total number of adverse events after the use of bismuth. Bismuth is safe and well-tolerated for the treatment of H. pylori. Moreover, with the availability of new single (three in one) capsule-containing bismuth substrate, metronidazole, and tetracycline, the number of tablets needs to be taken in the bismuth quadruple group will be substantially decreased and this will also likely increase drug compliance [28]. The only adverse event that occurred with significant frequency was dark stools [29]. In this study, the most adverse reaction of QT was the dark stool, too. Clinicians should, however, avoid the prescription of bismuth as a gastric mucosa protectant for long-term use.

ST has been reported to be more effective than standard triple therapy in many Asian countries. There was a difference among the eradication rates of ST in several countries, with 95%, in Thailand [30]; and 89%, in China [31]. In Turkey, previous studies that compared triple therapy and ST have showed various PP eradication rates ranging from 57% in ST to 88% [31-35].

Several studies showed that both ST and QT were highly effective and no difference in the eradication rate [36,37]. In addition, this study showed that eradication rates of QT and ST therapies were similar, too. The shortcoming of ST is just that the medications change during treatment and patients to consider it difficult to take the medicines.

CT involves the simultaneous use of a PPI and three types of antibiotics, although it could cause antibiotic abuse and unnecessary resistance. There was no difference in the effect of CT in clarithromycin-sensitive and resistant groups [38] as well as in metronidazole-sensitive and resistant groups [39]. Several studies showed that there was no difference in the effectiveness of CT and ST in clarithromycin and metronidazole-sensitive or resistant groups [40,41]. Moreover, this study showed that eradication rates of these two therapies were similar, too. Compared with ST, a benefit of CT is that the patient considers this treatment option simpler and shorter than the other options [42].

Our study directly compared QT, ST, and CT. When it was first conceived, the standard duration of ST was 10 days hence the other 2 arms were 10 days to be comparable. A longer treatment duration (14 vs. 7 days) has been shown to achieve higher treatment success in a meta-analysis. Our results showed that all three regimens were highly effective, with PP eradication rates of 94.2-95.8%. The lower ITT rate was due to the assumption that all patients who did not return for 13C-UBT failed treatment. Even so, ITT rate was 86.9%, 87.7%, and 86.9%, this rate was acceptable. These results suggest that all three regimens may be used, and given the convenience of ITT compared to ST and CT; TT still has an important role. These results support the conclusion of a retrospective study [43].

The PPI, rabeprazole was selected because we wanted to minimize the effect of CYP2C19 in locations where the homozygous extensive metabolizer of CYP2C19 was low, and the poor metabolizer was high.

The recent increase in clarithromycin resistance has markedly increased the number of targeted, prospective, multicenter, and randomized clinical trials. We compared all three of the therapies currently in use. This research was completed in a short period of time to minimize antibiotic resistance influenced by other factors and re-infection. Moreover, strength of this study was set in a location with a high prevalence of H. pylori and gastric cancer.

Another limitation of this study was that more accurate eradication rates could be obtained if we tested for H. pylori infection using two different methods and defined infection as positivity in both tests. Successful eradication would be defined as negative results for both tests, at which point a more accurate eradication rate could be assessed. To complement these data, we biopsied four in the different gastric mucosa, two in the gastric antrum and two in the gastric body and the samples were stained with Warthin–Starry. We also used the C13-urea breath test, which has a 98% accuracy rate.

CONCLUSION

To the best of our knowledge, our study (including 390 patients) is the first one which was compared three treatment choices and this study showed that eradication rates of QT, ST, and CT therapies are 94.2%, 95%, and 95.8%, respectively, with PP analyze, and there were significant difference among these three groups.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Cogo LL, Monteiro CL, Miguel MD, Miguel OG, Cunico MM, Ribeiro ML, et al. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of plant extracts traditionally used for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. Braz J Microbiol. 2010;41(2):304–9. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822010000200007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1517-83822010000200007 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1597–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1001110 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hentschel E, Brandstätter G, Dragosics B, Hirschl AM, Nemec H, Schütze K, et al. Effect of ranitidine and amoxicillin plus metronidazole on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and the recurrence of duodenal ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(5):308–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302043280503. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199302043280503 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chey WD, Wong BC. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1808–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection:The Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56(6):772–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.2006.101634 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, Ang TL, Hunt R, Talley NJ, et al. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(10):1587–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chung JW, Lee GH, Han JH, Jeong JY, Choi KS, Kim do H, et al. The trends of one-week first-line and second-line eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58(105):246–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Coelho LG, Maguinilk I, Zaterka S, Parente JM, do Carmo Friche Passos M, Moraes-Filho JP. 3rd Brazilian Consensus on Helicobacter pylori. Arq Gastroenterol. 2013;50(2):S0004–28032013005000113. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032013005000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jodlowski TZ, Lam S, Ashby CR., Jr Emerging therapies for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infections. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(11):1621–39. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1345/aph.1L234 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dib J, Jr, Alvarez B, Mendez L, Cruz ME. Efficacy of PPI, levofloxacin and amoxicillin in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori compared to conventional triple therapy at a Venezuelan hospital. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2013;14(3):123–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2013.09.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajg.2013.09.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cho DK, Park SY, Kee WJ, Lee JH, Ki HS, Yoon KW, et al. The trend of eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori infection and clinical factors that affect the eradication of first-line therapy. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55(6):368–75. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2010.55.6.368. http://dx.doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2010.55.6.368 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nadir I, Yonem O, Ozin Y, Kilic ZM, Sezgin O. Comparison of two different treatment protocols in Helicobacter pylori eradication. South Med J. 2011;104(2):102–5. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318200c209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318200c209 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liang X, Xu X, Zheng Q, Zhang W, Sun Q, Liu W, et al. Efficacy of bismuth-containing quadruple therapies for clarithromycin-, metronidazole-, and fluoroquinolone-resistant Helicobacter pylori infections in a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(7):802–7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection:Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(12):3069–79. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.555. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2009.555 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Essa AS, Kramer JR, Graham DY, Treiber G. Meta-analysis:Four-drug, three-antibiotic, non-bismuth-containing “concomitant therapy” versus triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2009;14(2):109–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00671.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00671.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Heo J, Jeon SW. Changes in the eradication rate of conventional triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2014;63(3):141–5. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2014.63.3.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Xu MH, Zhang GY, Li CJ. Efficacy of bismuth-based quadruple therapy as first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2011;40(3):327–31. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sun Q, Liang X, Zheng Q, Liu W, Xiao S, Gu W, et al. High efficacy of 14-day triple therapy-based, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for initial Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2010;15(3):233–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00758.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00758.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Agel E, Durmaz B, Tevfik MR, Asgın R. The isolation rate and antibiotic resistant pattern of Helicobacter pylori in dyspeptic patients. Turk J Med Sci. 2000;30:143–6. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Goral V, Fadile YZ, Guül K. Antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterohepatol. 2000;11:87–9. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Agah S, Shazad B, Abbaszadeh B. Comparison of azithromycin and metronidazole in a quadruple-therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication in dyspepsia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(4):225–8. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.56091. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/1319-3767.56091 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rogha M, Pourmoghaddas Z, Rezaee M, Shirneshan K, Shahi Z. Azithromycin effect on Helicobacter pylori eradication:Double blind randomized clinical trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56(91-92):722–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zullo A, De Francesco V, Scaccianoce G, Manes G, Efrati C, Hassan C, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with either quadruple regimen with lactoferrin or levofloxacin-based triple therapy:A multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39(9):806–10. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.05.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2007.05.021 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zheng Q, Chen WJ, Lu H, Sun QJ, Xiao SD. Comparison of the efficacy of triple versus quadruple therapy on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance. J Dig Dis. 2010;11(5):313–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00457.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00457.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cengiz N, Uslu Y, Gök F, Anarat A. Acute renal failure after overdose of colloidal bismuth subcitrate. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(9):1355–8. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1993-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00467-005-1993-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Huwez F, Pall A, Lyons D, Stewart MJ. Acute renal failure after overdose of colloidal bismuth subcitrate. Lancet. 1992;340(8830):1298. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93005-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(92)93005-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Noach LA, Eekhof JL, Bour LJ, Posthumus Meyjes FE, Tytgat GN, Ongerboer de Visser BW. Bismuth salts and neurotoxicity. A randomised, single-blind and controlled study. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1995;14(4):349–55. doi: 10.1177/096032719501400405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/096032719501400405 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Malfertheiner P, Bazzoli F, Delchier JC, Celiñski K, Giguère M, Rivière M, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy:A randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):905–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60020-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60020-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ford AC, Malfertheiner P, Giguere M, Santana J, Khan M, Moayyedi P. Adverse events with bismuth salts for Helicobacter pylori eradication:Systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(48):7361–70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7361. http://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.7361 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sirimontaporn N, Thong-Ngam D, Tumwasorn S, Mahachai V. Ten-day sequential therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection in Thailand. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(5):1071–5. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.708. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2009.708 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gao XZ, Qiao XL, Song WC, Wang XF, Liu F. Standard triple, bismuth pectin quadruple and sequential therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(34):4357–62. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i34.4357. http://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i34.4357 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yakut M, Çinar K, Seven G, Bahar K, Özden A. Sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21(3):206–11. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2010.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Demir M, Ataseven H. The effects of sequential treatment as a first-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Turk J Med Sci. 2011;41(3):427–33. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181eea6cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sezgin O, Altintas E, Nayir E, Uçbilek E. A pilot study evaluating sequential administration of a PPI-amoxicillin followed by a PPI-metronidazole-tetracycline in Turkey. Helicobacter. 2007;12(6):629–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00547.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00547.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Uygun A, Kadayifci A, Yesilova Z, Safali M, Ilgan S, Karaeren N. Comparison of sequential and standard triple-drug regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication:A 14-day, open-label, randomized, prospective, parallel-arm study in adult patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Clin Ther. 2008;30(3):528–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.03.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.03.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].McNicholl AG, Marin AC, Molina-Infante J, Castro M, Barrio J, Ducons J, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing sequential and concomitant therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication in routine clinical practice. Gut. 2014;63(2):244–9. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Liu KS, Hung IF, Seto WK, Tong T, Hsu AS, Lam FY, et al. Ten day sequential versus 10 day modified bismuth quadruple therapy as empirical firstline and secondline treatment for Helicobacter pylori in Chinese patients:An open label, randomised, crossover trial. Gut. 2014;63(9):1410–5. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306120 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Webber MA, Piddock LJ. The importance of efflux pumps in bacterial antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(1):9–11. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg050. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkg050 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Okada M, Nishimura H, Kawashima M, Okabe N, Maeda K, Seo M, et al. A new quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori:Influence of resistant strains on treatment outcome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(6):769–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00551.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00551.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, Opekun AR, Kuo CH, Wu IC, et al. Sequential and concomitant therapy with four drugs is equally effective for eradication of H. pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(1):36–41.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hsu PI, Wu DC, Chen WC, Tseng HH, Yu HC, Wang HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing 7-day triple, 10-day sequential, and 7-day concomitant therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(10):5936–42. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02922-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02922-14 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Dos Santos AA, Carvalho AA. Pharmacological therapy used in the elimination of Helicobacter pylori infection:A review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(1):139–54. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ang TL, Wang L, Ang D, Chiam P, Fock KM, Teo EK. Is there still a role for empiric first-line triple therapy using proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin and clarithromycin for Helicobacter pylori infection in Singapore? Results of a time trend analysis. J Dig Dis. 2013;14(2):100–4. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1751-2980.12024 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]