Abstract

Frequent use of websites and mobile telephone applications (apps) by men who have sex with men (MSM) to meet sexual partners, commonly referred to as “hookup” sites, make them ideal platforms for HIV prevention messaging. This Rhode Island case study demonstrated widespread use of hookup sites among MSM recently diagnosed with HIV. We present the advertising prices and corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs of the top five sites used by newly diagnosed HIV-positive MSM to meet sexual partners: Grindr, Adam4Adam, Manhunt, Scruff, and Craigslist. Craigslist offered universal free advertising. Scruff offered free online advertising to selected nonprofit organizations. Grindr and Manhunt offered reduced, but widely varying, pricing for nonprofit advertisers. More than half (60%, 26/43) of newly diagnosed MSM reported meeting sexual partners online in the 12 months prior to their diagnosis. Opportunities for public health agencies to promote HIV-related health messaging on these sites were limited. Partnering with hookup sites to reach high-risk MSM for HIV prevention and treatment messaging is an important public health opportunity for reducing disease transmission risks in Rhode Island and across the United States.

An estimated 1.2 million people in the United States live with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) according to 2015 estimates published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1 Although men who have sex with men (MSM) represent 4% of the U.S. male population, they account for 61% of all new HIV infections.2 Sexual behaviors contributing to HIV transmission among MSM may be facilitated by websites and mobile telephone applications (apps), which are increasingly popular vehicles for MSM to meet sexual partners.3–8 Although websites and apps differ in services offered and message delivery, many have the primary purpose of facilitating sexual encounters. Hereinafter, we collectively refer to websites and apps that MSM use to meet sexual partners as “hookup sites.” Some hookup sites use global positioning system software to allow subscribers to identify nearby sexual partners.8

Use of hookup sites to meet sexual partners among MSM is more prevalent than among other populations. MSM are up to seven times more likely than non-MSM to have sex with a partner they met online,5 and an estimated 3–6 million MSM meet sexual partners using Internet-based technology.7 A meta-analysis found that nearly half of MSM surveyed had met sexual partners online;7 another study found that 85% of MSM use the Internet to meet other men for sex.5 The anonymity, affordability, and accessibility of meeting partners online appeals to many MSM, for whom meeting partners in traditional social settings may pose challenges because of stigma associated with having sex with other men.9

MSM who use the Internet to meet sexual partners are more likely to engage in higher-risk behavior than men who do not meet partners online, including having more frequent condomless anal intercourse, having more sexual partners, having more sex with anonymous or non-main partners, having more sex with HIV-positive partners, and more often using drugs and alcohol during sex.4,8,10,11 Hookup sites can be used to locate partners for “barebacking,” or intentional condomless sex.3,8 Men who meet partners online may have limited knowledge of HIV prevention tools; a 2012 study found that MSM who met partners online had limited knowledge about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and postexposure prophylaxis.12

Despite the growing body of research linking hookup sites to high-risk behavior, few studies have explored the associations between these sites and disease transmission. A 2014 study found that MSM who used apps to meet sexual partners had greater odds of testing positive for gonorrhea and chlamydia compared with MSM who did not meet their partners online, but did not find any increased risk for syphilis or HIV.4 Although another 2014 article posited that Craigslist advertisements for sexual encounters were correlated with HIV infection, a closer review of the analyses suggested that transmission was not correlated with Craigslist use at the individual level.6 These findings suggest that hookup sites may facilitate disease transmission by expediting the process of meeting sexual partners,9 but this issue warrants further scientific exploration and public policy attention.

PURPOSE

From 2007 to 2011, the number of annual new HIV diagnoses in Rhode Island declined from 121 to 97, but the percentage of newly diagnosed individuals who were MSM increased during that time from 47 of 121 (39%) to 62 of 97 (64%).13 More recently, the number of new HIV diagnoses increased 31%, from 74 new diagnoses in 2013 to 97 new diagnoses in 2014, mostly among MSM.14 Twenty-seven percent of individuals newly diagnosed with HIV between 2009 and 2013 presented with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).13 To better understand the HIV epidemic in Rhode Island, we characterized the role of hookup sites among newly diagnosed MSM in Rhode Island and explored opportunities for delivering prevention messaging through these sites. To our knowledge, few HIV prevention messages are delivered on hookup sites in Rhode Island. We then contacted the most commonly identified hookup sites about pricing for online advertising for HIV prevention and testing messages, as well as their corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs. CSR focuses on implementing or supporting programs that take responsibility for the company's actions and encourage or support a positive impact on the community.

METHODS

To help characterize the sexual networks and risk behaviors that influence HIV infection in Rhode Island, we attempted to interview all 74 individuals newly diagnosed with HIV in Rhode Island in 2013. HIV diagnoses in Rhode Island are reported by patient name to the Rhode Island Department of Health. Patients were recruited from all major HIV outpatient clinics in the state. Demographic, behavioral, and laboratory information were obtained from standardized survey questions and review of clinical data. We conducted individual interviews to collect in-depth contextual data, including where patients met sexual partners in the 12 months preceding their HIV diagnosis and where they met the person they believed infected them with HIV. Interviews were conducted in person by research staff members at The Miriam Hospital Immunology Center, which was the primary study site. Patients received a $75 gift card for participating in the study, which was part of a larger study with more in-depth survey questions and a blood draw.

Based on in-depth interviews, we determined the single most likely risk factor for HIV infection for each patient based on the following risk groups: MSM, males who have sex with females, females who have sex with males, and injection drug users (IDUs). Groups were mutually exclusive; IDUs engaging in one of the specified categories of sexual behavior were grouped on the basis of IDU behavior. We performed bivariate analyses comparing MSM with non-MSM using log binomial regression, with significance defined as p<0.05, and calculated unadjusted relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We conducted analyses using SAS® version 9.4.15

From December 1, 2013, to January 1, 2015, we contacted the five hookup sites by e-mail and telephone that were most commonly reported by our patients. We inquired about advertising pricing in Rhode Island and any CSR policies. We requested pricing estimates for advertising, including promoting information about HIV testing and treatment, PrEP and postexposure prophylaxis, and other prevention messaging. Our inquiries focused on pricing for various advertising options, including banner advertisements, bulk e-mails, and pop-up advertisements. Pricing was often based on “share of voice,” which measures the fraction of advertising reserved for each message;16 capturing at least 20% share of voice is often considered a useful benchmark for effectively penetrating a market with messaging. This term refers to the percentage of all online content and conversations for a message relative to other messages. “Cost per thousand impressions” (CPM) was another commonly used metric to price the cost per number of consumer views of messages; this term refers to the total price of advertising per 1,000 views. Some companies base pricing on share of voice, while others base pricing on CPM.

OUTCOMES

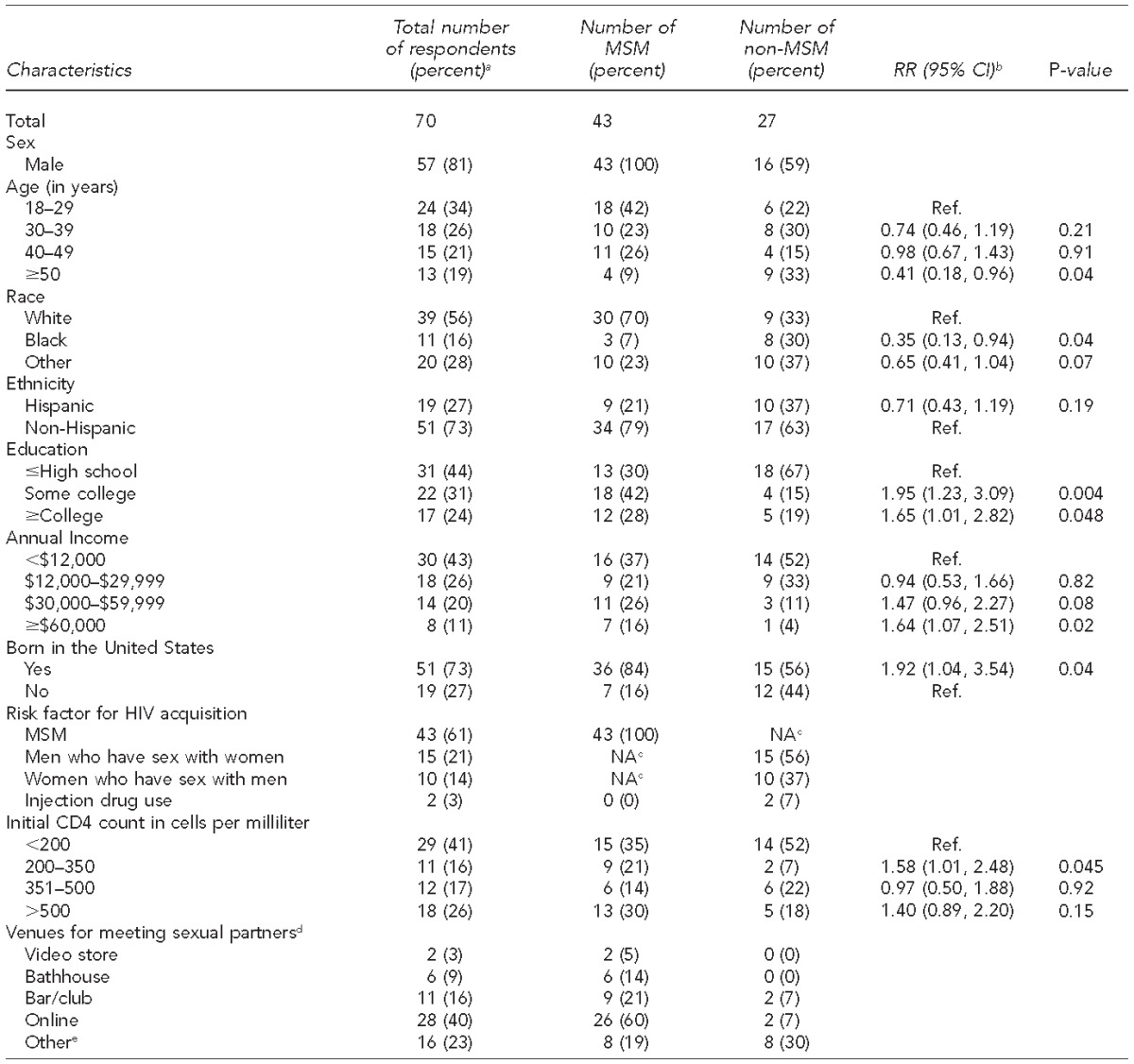

Of the 74 individuals diagnosed with HIV in Rhode Island during 2013, 70 (95%) were interviewed; the remaining four individuals either could not be reached or declined to participate. Of the 70 individuals interviewed, most were men (n=57, 81%), self-identified as white (n=39, 56%), and were younger than 40 years of age (n=42, 60%). Twenty-nine individuals (41%) had a CD4 cell count <200 cells per milliliter upon diagnosis. The most common risk group was MSM (n=43, 61%). Compared with other risk groups, newly diagnosed MSM were more likely to be white, have a higher level of education, and have an annual income >$30,000 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study respondents newly diagnosed with HIV, Rhode Island, 2013

aA total of 74 people were newly diagnosed with HIV in Rhode Island in 2013, of whom 70 people were interviewed and included in the analysis. Percentages may not total to 100 due to rounding.

bUnadjusted RR was calculated via bivariable log binomial models and represents the increase (RR>1.0) or decrease (RR<1.0) in risk for having a particular demographic characteristic for MSM relative to non-MSM. Significance was defined as p<0.05.

cIndicates this risk factor does not apply to this population

dCategories are not mutually exclusive; as such, column totals may exceed 100%. The small number of non-MSM precluded estimation of RR for the venues for meeting sexual partners.

e“Other” includes any venue for meeting sexual partners (cruising area, sex party, gym), other than those already specified, provided in response to the question, “In the 12 months before you tested positive for HIV, where did you meet sexual partners in Rhode Island?”

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

MSM = men who have sex with men

RR = relative risk

CI = confidence interval

NA = not applicable

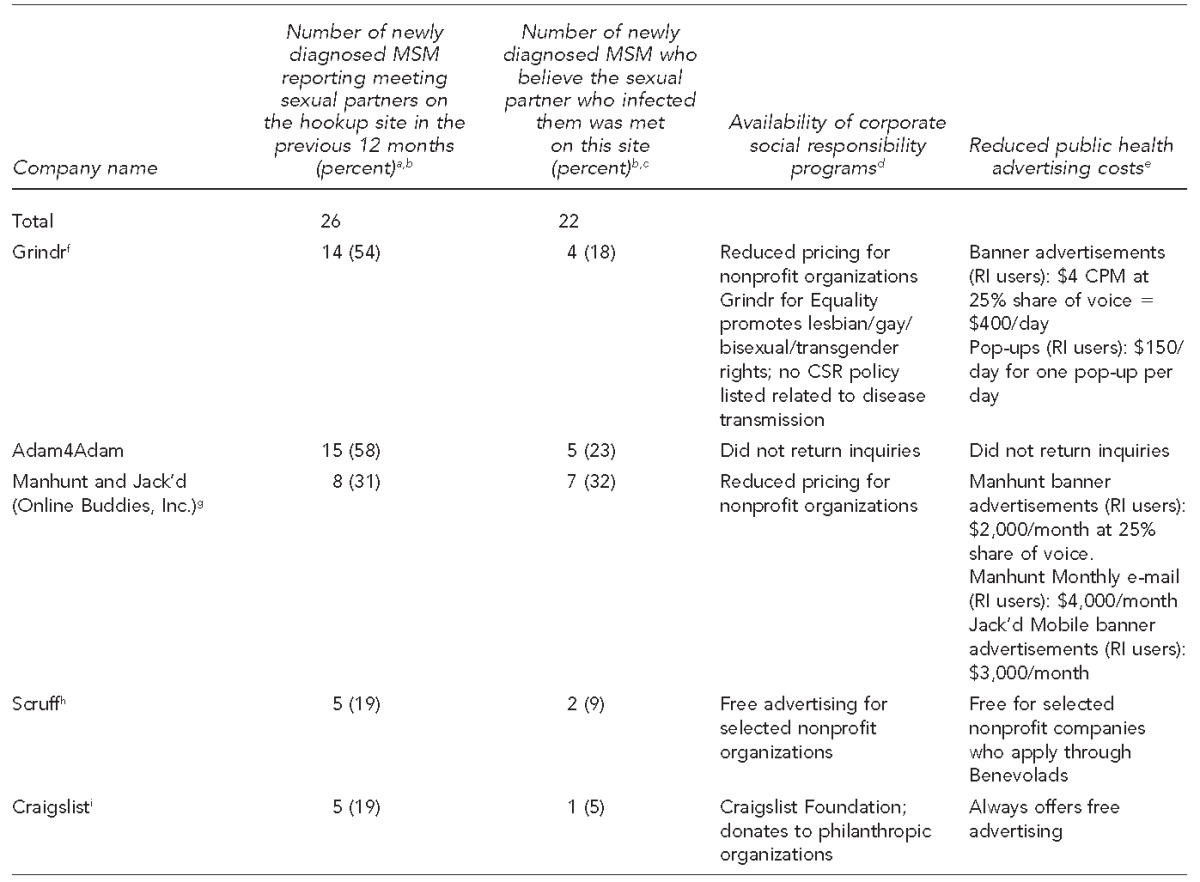

Newly diagnosed MSM were more likely than newly diagnosed non-MSM to report meeting sexual partners online in the 12 months prior to their diagnosis (odds ratio [OR] = 19.1, 95% CI 4.0, 91.4; p<0.01). Twenty-two of 43 MSM (51%) believed they met the person(s) who infected them online, most commonly on Grindr, Manhunt, Scruff, Adam4Adam, or Craigslist (Table 2). Pricing and services offered by these five hookup sites varied widely. Only Craigslist and Scruff provided mechanisms for free public health advertising, either for all public health organizations (Craigslist) or for selected nonprofit organizations on an application basis (Scruff) (Table 2). Scruff had a formal CSR policy readily accessible to the public and was the only site with a formal program for free public health advertising for nonprofit organizations.

Table 2.

Characteristics of hookup websites and apps used by newly diagnosed HIV-positive men who have sex with men, Rhode Island, 2013

aTwenty-six of 43 newly diagnosed MSM reported meeting sexual partners online in the 12 months prior to HIV diagnosis.

bPercentages do not sum to 100 because many participants used more than one hookup site.

cTwenty-two of 43 newly diagnosed MSM believed the person who infected them was someone they met online.

dCorporate social responsibility (CSR) programs focus on initiatives that take responsibility for the company's actions and encourage a positive impact on the community.

eShare of voice is used to measure the fraction of advertising reserved for each message and refers to the percentage of all online content and conversations for a message relative to other messages. Cost per thousand impressions is a metric used to price the cost per number of consumer views of messages; this term refers to the total price of advertising per 1,000 views.

fSource: Grindr. Advertise with Grindr [cited 2015 Dec 30]. Available from: http://grindr.com/advertise

gSource: Online Buddies. OLB Research Institute [cited 2015 Dec 30]. Available from: http://online-buddies.com/products/olb-research-institute

hSource: Scruff. Benevolads [cited 2015 Dec 30]. Available from: https://ads.scruff.com

iSource: Craigslist [cited 2015 Dec 30]. Available from: http://craigslist.org/about/sites

apps = applications

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

MSM = men who have sex with men

CPM = cost per 1,000 impressions

RI = Rhode Island

Grindr offered paid advertising at discounted rates for nonprofit organizations. Grindr, available only as a mobile telephone app, offered an $8 CPM rate ($8 for 1,000 impressions) for banner advertising for general advertisers. A 25% share of voice would require 50,000 daily impressions at $400 per day (50 3 $8 per 1,000 impressions). Grindr offered a reduced rate of $4 for 1,000 impressions for nonprofit organizations. Grindr also offered broadcast messaging, or pop-up text advertisements, viewable at first login to the mobile app. A single pop-up advertisement to all Rhode Island users was $250 per day for general advertisers and $150 per day for nonprofit organizations. Grindr did not offer e-mail advertising (Table 2).

Manhunt offered advertising at a lower contract minimum to nonprofit organizations than rates for corporate advertisers. Manhunt required a $2,000 contract minimum for nonprofit organizations to send once-monthly e-mails to Manhunt users throughout Rhode Island and a $1,000 contract minimum for desktop or mobile display banner advertisements at a 25% share of voice (Table 2). Manhunt capped health-related advertising at 50% share of voice and offered advertising services targeted to specific populations among their user base at additional, unspecified rates. Manhunt did not offer pop-up advertising on desktop or mobile devices. Adam4Adam did not respond to multiple inquiries about advertising prices.

LESSONS LEARNED

Frequent use of hookup sites among newly diagnosed MSM, many of whom presented to care with an AIDS diagnosis, underscores the importance of disseminating prevention and treatment messaging online. Although partnerships between health-promotion agencies and hookup sites offer an opportunity to reach high-risk MSM, we encountered challenges in communicating with companies. For example, one company did not respond to multiple inquiries about pricing and CSR programs. Although Craigslist offers free advertising and Scruff moved toward a free advertising model for selected organizations following an application process, many companies' current prices may be prohibitively high for health-promotion agencies and may present barriers for disseminating prevention messaging.

Given the frequent role of hookup sites for meeting sexual partners among newly diagnosed MSM and their potential association with HIV and other sexually transmitted infection (STI) risks, health-promotion agencies should do more to engage hookup companies in promoting prevention efforts. The San Francisco AIDS Foundation helped jumpstart this engagement in 2012; several hookup companies participated in a conference and committed to promoting HIV/STI testing, reducing stigma, and collaborating with public health partners to disseminate information.17 However, absent from that conference were many of the most popular hookup companies, including Manhunt, Adam4Adam, and Jack'd (Manhunt and Jack'd are owned by Online Buddies Inc.). Greater than AIDS, an HIV media campaign of the Kaiser Family Foundation, has launched campaigns on Grindr, Jack'd, and YouTube.18

Since we completed data collection, several companies' policies and programs related to disease prevention and sexual health have evolved. Adam4Adam, Manhunt, and Scruff now include opportunities for users to indicate if they currently take PrEP. Grindr has “Grindr for Equality” to promote educational messaging and has a “Health” page on its website that provides information on sexual health resources.19,20 Grindr also recently announced a partnership with Gilead Sciences and the San Francisco AIDS Foundation to survey its users about PrEP use. Grindr subsequently announced it would list maps and resources to help Grindr users identify local PrEP providers.20

Adam4Adam also has a “Health” page that provides sexual health resources.21 Manhunt Cares (http://www.manhuntcares.com) is a separate website linked to Manhunt that provides sexual health information and information about health products and research studies related to the Manhunt site. In 2014, Scruff commenced its Benevolads advertising program, which is marketed as free, geo-targeted advertising for nonprofits to create, publish, and track data on the reach of advertisements directed toward the MSM community.22 Although these programs represent movement toward health promotion, more should be done by, and in partnership with, these companies to effectively disseminate information about HIV prevention interventions. Improved and expanded engagement in HIV prevention will require increased spending on messaging by private and public sectors. Our findings suggest that hookup sites already reach populations at highest risk, and public health partnerships should capitalize on this opportunity to promote prevention messaging as well as enhanced screening and treatment services.23,24

Hookup sites are accepted by MSM for HIV prevention and sexual health messaging, and some companies report a willingness to support HIV prevention programs.17,24 How best to promote HIV testing and treatment is unclear. Implementation science should explore various approaches. Given that most users visit hookup sites with the express purpose of identifying sexual partners, prevention messaging that leads with sex-positive information may resonate more with users than messages that lead or focus exclusively on risk reduction.5,24 In addition, most hookup sites are profit-driven and their services are already widely used by MSM. Communication strategies that support companies' business goals while appealing to their users and allowing for delivery of important prevention messaging are needed. It may also be important to promote messages that stimulate demand for screening and treatment services at local clinics. Further research is needed to explore which messages resonate most with consumers and respond to their sexual health needs; this research will require collaboration across sectors, including government agencies, hookup sites, users, and researchers.

Our results suggest a need for broad-based CSR programs that focus on reducing disease transmission among MSM using hookup sites. The tobacco, soft drink, and alcohol industries have almost universally adopted CSR programs in response to consumer demands. Additionally, advertising prices for many companies might be prohibitively high for health promotion. As part of CSR policies, companies should implement deep discounts for advertising for government and nonprofit agencies whose missions are related to health promotion.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. Patient interviews relied on self-reported behaviors. To help mitigate recall bias, we encouraged respondents to comment on how they met sexual partners in the previous 12 months. Our results may be subject to recall bias, particularly when we asked individuals who were diagnosed late in the course of their disease where they met the partner who may have infected them. We also did not ask about frequency of hookup site use and associated coital frequency, which limited our ability to link HIV transmission to specific hookup sites. Additionally, because we were focused on the hookup sites reported by participants rather than sites used by MSM nationwide, it is unclear how representative our findings may be for the broader MSM community. Moreover, because this study focused on a small sample of HIV-positive MSM, we also cannot extrapolate our findings to the broader MSM community. Lastly, between the time we collected data and the time the study was published, company policies and app use may have changed, particularly given the rapid pace of change in apps. We nevertheless believe that our findings suggest important and timely opportunities to enhance HIV prevention by partnering with online sites.

CONCLUSION

Although multiple factors contribute to higher rates of HIV among MSM, including social stigma and other complex behavioral and social factors, most newly diagnosed MSM in Rhode Island met one or more recent sexual partners online. Results from this study suggest that hookup sites' digital platforms may present opportunities for social marketing programs focused on reducing HIV transmission and engaging HIV-positive men in care earlier in the course of their infection. These results highlight a public health crisis among MSM and are not intended to further stigmatize an already marginalized community in need of public health resources. We hope our findings are used as a call to action for greater public health collaboration to address the sexual health needs of MSM. Ubiquitous use of hookup sites nationwide warrants urgent and nationwide public policy attention, innovative research, programmatic partnerships, and investment from the public and private sectors.

Footnotes

Philip A. Chan is supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant #K23AI096923. Amy Nunn is supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grant #K01AA020228. Additional support was provided by the Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853). Amy Nunn and Philip Chan have received grant support from Gilead Sciences, Inc. Amy Nunn has received consulting fees from Mylan Inc. E. Karina Santamaria is supported by several training grants from the National Institutes of Health (R25GM083270, R25MH83620, and T32DA013911). The study protocol was approved by The Miriam Hospital Institutional Review Board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PloS One. 2011;6:e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. HIV among gay and bisexual men. 2012 [cited 2015 May 28] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library_factsheet_hiv_among_gaybisexualmen.pdf.

- 3.Berg RC. Barebacking among MSM Internet users. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:822–33. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beymer MR, Weiss RE, Bolan RK, Rudy ET, Bourque LB, Rodriguez JP, et al. Sex on demand: geosocial networking phone apps and risk of sexually transmitted infections among a cross-sectional sample of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles County. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:567–72. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bull SS, McFarlane M, Rietmeijer C. HIV and sexually transmitted infection risk behaviors among men seeking sex with men on-line. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:988–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan J, Ghose A. Internet's dirty secret: assessing the impact of online intermediaries on HIV transmission. MIS Q. 2014;38:955–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenness SM, Neaigus A, Hagan H, Wendel T, Gelpi-Acosta C, Murrill CS. Reconsidering the Internet as an HIV/STD risk for men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1353–61. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landovitz RJ, Tseng CH, Weissman M, Haymer M, Mendenhall B, Rogers K, et al. Epidemiology, sexual risk behavior, and HIV prevention practices of men who have sex with men using GRINDR in Los Angeles, California. J Urban Health. 2013;90:729–39. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9766-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosser BR, Wilkerson JM, Smolenski DJ, Oakes JM, Konstan J, Horvath KJ, et al. The future of Internet-based HIV prevention: a report on key findings from the Men's INTernet (MINTS-I, II) Sex Studies. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S91–100. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9910-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liau A, Millett G, Marks G. Meta-analytic examination of online sex-seeking and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:576–84. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204710.35332.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DM, Drumright LN, Frost SD, Cheng WS, Espitia S, Daar ES, et al. Characteristics of recently HIV-infected men who use the Internet to find male sex partners and sexual practices with those partners. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:582–7. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243100.49899.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ, Rosenberger JG, Novak DS, Mitty JA, White JM, et al. Limited awareness and low immediate uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men using an Internet social networking site. PloS One. 2012;7:e33119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhode Island Department of Health, Division of Infectious Disease and Epidemiology, Office of HIV/AIDS and Viral Hepatitis. Providence (RI): Division of Infectious Disease and Epidemiology; 2013. 2012 Rhode Island HIV/AIDS/viral hepatitis epidemiologic profile with surrogate data. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhode Island Department of Health. Providence (RI): Rhode Island Department of Health; 2016. 2014 HIV surveillance report. [Google Scholar]

- 15.SAS Institute, Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2013. SAS®: Version 9.4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Guinn TC, Allen C, Semenik RJ. 6th ed. Mason (OH): South-Western CENGAGE Learning; 2011. Advertising and integrating brand promotion. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wohlfeiler D, Hecht J, Volk J, Fisher Raymond H, Kennedy T, McFarland W. How can we improve online HIV and STD prevention for men who have sex with men? Perspectives of hook-up website owners, website users, and HIV/STD directors. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:3024–33. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0375-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WE > AIDS. Greater than AIDS tools [cited 2016 Jan 7] Available from: http://www.greaterthan.org/toolkit/#speak-out.

- 19.Grindr. Grindr for Equality: our next imperative. 2015 Jun 10 [cited 2016 Jan 22] Available from: http://www.grindr.com/blog/grindr-for-equality-our-next-imperative.

- 20.Grindr. Health resources [2016 Jan 22] Available from: http://www.grindr.com/?s=health.

- 21.Adam4Adam. Health resources [cited 2016 Jan 7] Available from: http://www.adam4adam.com/pages/health.

- 22.Perry Street Software, Inc. Benevolads: FREE advertising for non-profits [cited 2016 Jan 7] Available from: https://ads.scruff.com.

- 23.Grov C, Breslow AS, Newcomb ME, Rosenberger JG, Bauermeister JA. Gay and bisexual men's use of the Internet: research from the 1990s through 2013. J Sex Res. 2014;51:390–409. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.871626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenberger JG, Reece M, Novak DS, Mayer KH. The Internet as a valuable tool for promoting a new framework for sexual health among gay men and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S88–90. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9897-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]