Abstract

Objectives

We described the following among U.S. primary care physicians: (1) perceived importance of vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices relative to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) preventive services, (2) attitudes toward the U.S. adult immunization schedule, and (3) awareness and use of Medicare preventive service visits.

Methods

We conducted an Internet and mail survey from March to June 2012 among national networks of general internists and family physicians.

Results

We received responses from 352 of 445 (79%) general internists and 255 of 409 (62%) family physicians. For a 67-year-old hypothetical patient, 540/606 (89%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 87, 92) of physicians ranked seasonal influenza vaccine and 487/607 (80%, 95% CI 77, 83) ranked pneumococcal vaccine as very important, whereas 381/604 (63%, 95% CI 59, 67) ranked Tdap/Td vaccine and 288/607 (47%, 95% CI 43, 51) ranked herpes zoster vaccine as very important (p<0.001). All Grade A USPSTF recommendations were considered more important than Tdap/Td and herpes zoster vaccines. For the hypothetical patient aged 30 years, the number and percentage of physicians who reported that the Tdap/Td vaccine (377/604; 62%, 95% CI 59, 66) is very important was greater than the number and percentage who reported that the seasonal influenza vaccine (263/605; 43%, 95% CI 40, 47) is very important (p<0.001), and all Grade A and Grade B USPSTF recommendations were more often reported as very important than was any vaccine. A total of 172 of 587 physicians (29%) found aspects of the adult immunization schedule confusing. Among physicians aware of “Welcome to Medicare” and annual wellness visits, 492/514 (96%, 95% CI 94, 97) and 329/496 (66%, 95% CI 62, 70), respectively, reported having conducted fewer than 10 such visits in the previous month.

Conclusions

Despite lack of prioritization of vaccines by ACIP, physicians are prioritizing some vaccines over others and ranking some vaccines below other preventive services. These attitudes and confusion about the immunization schedule may result in missed opportunities for vaccination. Medicare preventive visits are not being used widely despite offering a venue for delivery of preventive services, including vaccinations.

Two widely used sets of national recommendations to guide delivery of preventive care are from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)1 and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).2–5 USPSTF is an independent panel of primary care providers who are experts in evidence-based medicine. USPSTF conducts scientific evidence reviews of clinical preventive services and grades their recommendations, based on the evidence, as A (strongly recommends), B (recommends), C (no recommendation), D (not recommended), and I (insufficient evidence to make a recommendation). USPSTF defers vaccine recommendations to ACIP. ACIP is a group of 15 experts in vaccination who review evidence and make recommendations to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on the use of vaccines. ACIP publishes adult and pediatric immunization schedules annually and in 2010 adopted a framework for developing evidence-based recommendations based on the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach.6

Despite these recommendations, use of all recommended preventive services among adults is below national goals.7–10 The proportion of women aged 50–74 years who received a mammogram within the previous two years in 2010—a USPSTF Grade B recommendation—was 80%;11 the proportion of adults aged 50–75 years who had colorectal cancer screening in 2010—a USPSTF Grade A recommendation—was 65%;11 and the proportion of adults aged 18–64 years who received a seasonal influenza vaccine during the 2013–2014 season—an ACIP recommendation—was 37%.12

Several provisions in the Affordable Care Act were designed to promote delivery of preventive services.8,13 The law increases access to these services by (1) expanding health insurance coverage, (2) requiring that USPSTF Grade A and Grade B services and ACIP-recommended vaccines be provided without cost to patients with nongrandfathered private insurance plans, and (3) requiring that USPSTF Grade A and Grade B services covered by Medicare be provided at no cost to beneficiaries.14,15 In addition, the law created a new venue for preventive service delivery for Medicare beneficiaries: the annual wellness visit.16 Like the “Welcome to Medicare” visit,17 which was introduced in 2005, the annual wellness visit requires establishment of a preventive care plan.

Delivering all recommended preventive services to an adult patient is challenging. The complexity and number of tasks per visit are increasing.18,19 The nonvisit workload for physicians is also substantial.20 Providing USPSTF and immunization preventive services to a panel of 2,500 patients during one year was estimated in 2003 to require 7.4 hours per physician working day;21 now more preventive services are recommended. It follows that physicians make choices about which preventive services to provide during the limited time allotted for a primary care visit.

Because vaccination rates for many recommended vaccines for adults are lower than rates for other adult preventive services, and the physician perspective on Medicare preventive service visits has not been studied, we sought to describe the following among U.S. primary care physicians: (1) the perceived importance of ACIP-recommended vaccines relative to USPSTF preventive services, (2) attitudes toward the U.S. adult immunization schedule, and (3) awareness and use of Medicare preventive service visits.

METHODS

Study setting

From March to June 2012, we administered a survey to a national network of physicians who spent at least 50% of their time practicing primary care.

Study population

The Vaccine Policy Collaborative Initiative,22 a survey mechanism to assess physician attitudes toward vaccine issues in collaboration with CDC, conducted the survey. We developed two sentinel networks of primary care physicians by recruiting family physicians in 2011 from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and general internists in 2012 from the American College of Physicians (ACP). We conducted quota sampling23 to ensure that sentinel networks of physicians were similar to ACP and AAFP memberships by region, by location (urban vs. rural), and by practice setting (general internists only). We demonstrated in 2008 that survey responses from network physicians and those of physicians randomly sampled from physician databases of the American Medical Association were similar in demographic characteristics, practice attributes, and attitudes toward a range of vaccination issues.23 All physicians in both networks were eligible to take the survey.

Survey design

In a survey about adult vaccine delivery,24 we asked physicians about their attitudes toward the importance of 2012 USPSTF1 and ACIP2 recommendations for a hypothetical, sex-neutral, nonsmoking, healthy patient aged 30 years and the same hypothetical patient aged 67 years. These hypothetical patients were chosen to capture information on attitudes toward vaccination for two distinct age groups and to eliminate the influence of any high-risk conditions on the providers' decisions on how to prioritize preventive services. To control for insurance coverage as a potential confounder, we asked respondents to assume that all services were covered by insurance. The survey did not indicate the grade of the USPSTF recommendation. We provided respondents with information about Welcome to Medicare and the Medicare annual wellness visit and asked questions about these two programs. We also assessed attitudes toward the adult immunization schedule. We used four-point Likert scales to assess the importance of USPSTF and ACIP recommendations (from 1 = very important to 4 = not at all important) and attitudes toward the adult immunization schedule (from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree). A national advisory panel of six general internists and seven family physicians pretested the survey, which was modified according to their feedback. We pilot-tested the survey among 63 general internists and 23 family physicians nationally and further modified the survey according to their feedback.

Survey administration

We sent the survey via the Internet (Verint Systems, Inc., Melville, New York) or through the U.S. Postal Service, according to physician preference. We sent an initial e-mail to the Internet group with up to eight e-mail reminders, and we sent an initial mailing to the mail group and up to two additional reminders. Nonrespondents in the Internet group were also sent a mail survey in case of problems with e-mail correspondence. We patterned the mail protocol on Dillman's tailored design method,25 an approach to designing surveys that emphasizes giving attention to all aspects of surveys and survey implementation experienced by survey recipients. No incentives to complete the survey were provided.

Statistical analysis

We pooled Internet and mail surveys for analyses because other studies found that information on physician attitudes are similar when obtained by either method.25–27 We compared the characteristics of respondents and nonrespondents by using Wilcoxon and c2 analyses. Data on nonrespondent characteristics were obtained from the recruitment survey for the sentinel networks. We compared the responses of general internists and family physicians by using c2 tests and Mantel–Haenszel c2 tests. Most of the responses of general internists and family physicians were similar; therefore, we combined results for both specialties and highlighted any significant differences. For analyses evaluating associations with physician awareness and use of Medicare preventive care visits, we divided the physicians into two groups by percentage of Medicare patients in the physician's practice (<25% and ≥25%). Analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.4.28

RESULTS

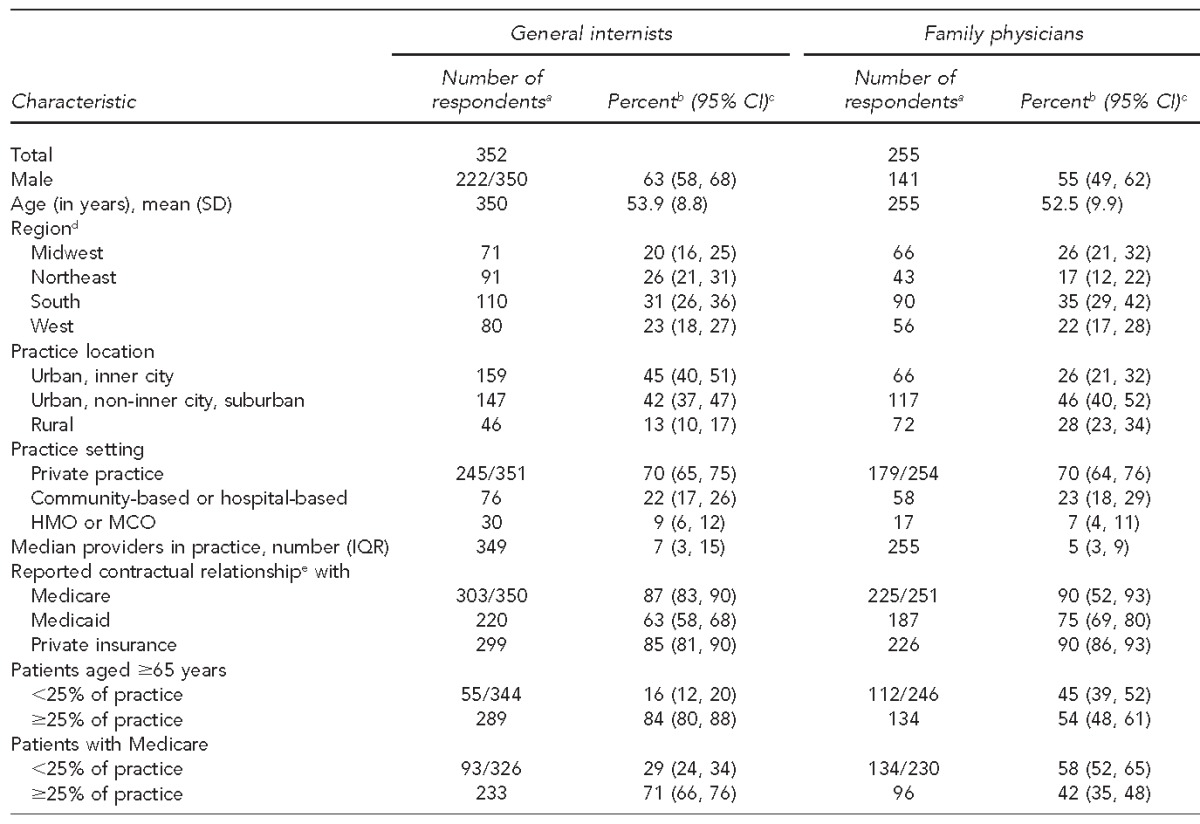

We received responses from 352 of 443 (79%) general internists and 255 of 409 (62%) family physicians, for a total of 607 respondents. Respondents and nonrespondents did not differ significantly by sex, age, region, practice location, practice setting, or number of providers in the practice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and practice characteristics of survey respondents, by physician specialty, in a study of physician attitudes toward adult vaccines and other preventive practices, United States, 2012

aDenominators that differ from total number of respondents are indicated and apply to all values in the category indicated.

bSome column percentages do not total to 100 because of rounding.

cExcept for age (mean [SD] years) and providers in practice (median [IQR])

dAccording to the U.S. Census Bureau regions established in 1942. Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin; Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, West Virginia; West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming.

cRespondents reported having a contractual relationship with these entities.

CI = confidence interval

SD = standard deviation

HMO = health maintenance organization

MCO = managed care organization

IQR = interquartile range

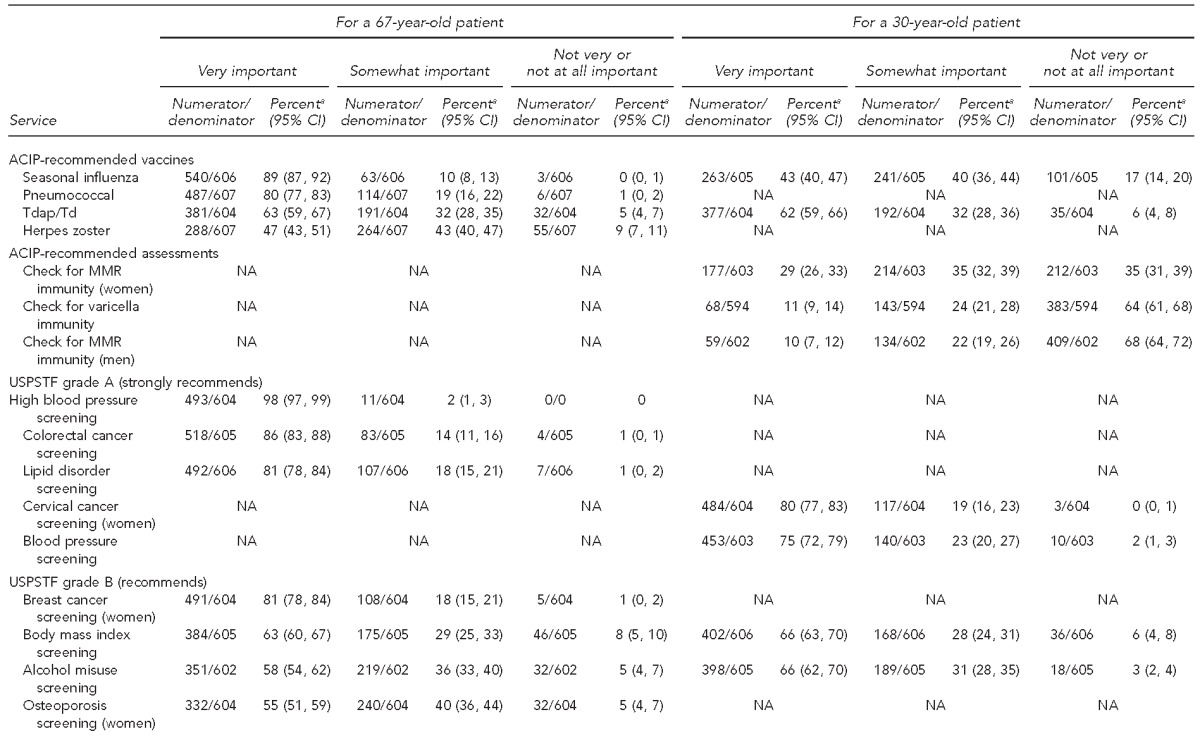

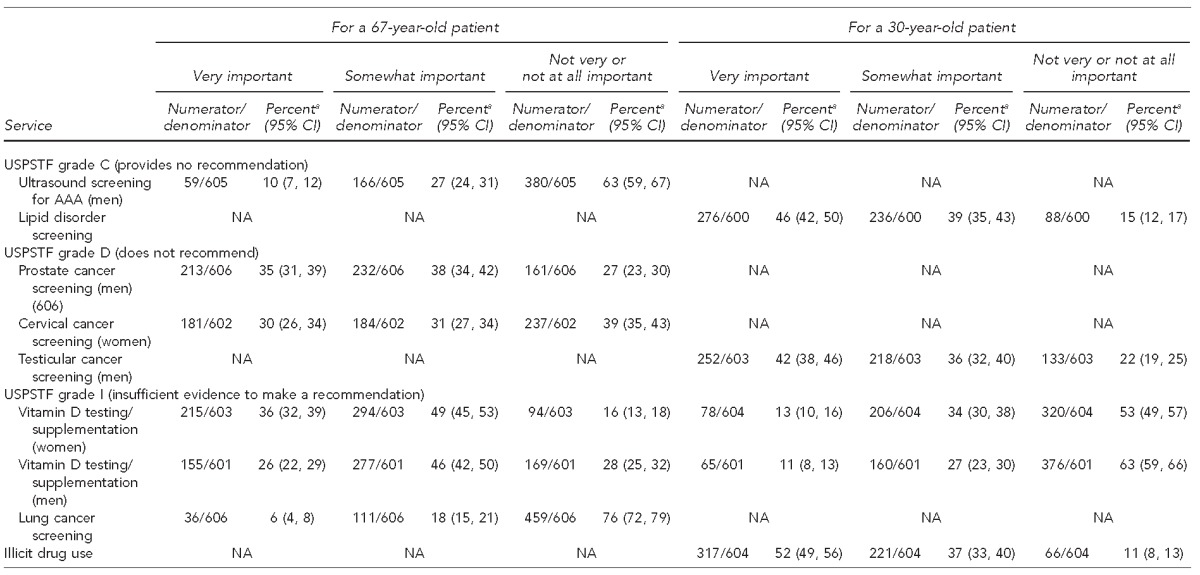

For the hypothetical patient aged 67 years, the number and percentage of physicians who reported that seasonal influenza vaccine (540/606; 89%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 87, 92) and pneumococcal vaccine (487/607; 80%, 95% CI 77, 83]) are very important was greater than the number and percentage who reported that the tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis/tetanus, diphtheria (Tdap/Td) vaccine (381/604; 63%, 95% CI 59, 67) and herpes zoster vaccine (288/607; 47%, 95% CI 43, 51) are very important (p<0.001) (Table 2). Physicians were more likely to report all grade A recommendations as more important than the herpes zoster or Tdap/Td vaccine and all grade B recommendations as more important than the herpes zoster vaccine. Preventive services for a hypothetical patient aged 67 years that are not recommended (Grade D) or have insufficient evidence (Grade I) were more often reported to be very important than were services without a recommendation (Grade C).

Table 2.

Physician attitudes toward importance of various preventive services for nonsmoking healthy patients in a survey of general internists and family physicians (n=607) on attitudes toward adult vaccines and other preventive practices, United States, 2012

aSome row percentages do not total to 100 because of rounding.

CI = confidence interval

ACIP = Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

Tdap/Td = tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis/tetanus, diphtheria

MMR = measles, mumps, rubella

USPSTF = U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm

NA = not applicable

For the hypothetical patient aged 30 years, the number and percentage of physicians who reported that the Tdap/Td vaccine (377/604; 62%, 95% CI 59, 66) is very important was greater than the number and percentage who reported that the seasonal influenza vaccine (263/605; 43%, 95% CI 40, 47) is very important (p<0.001) (Table 2). Both Grade A and Grade B USPSTF recommendations for this patient were more often reported as being very important than was any vaccine-related preventive service. Generally, the lower the grade of the USPSTF recommendation, the lower the percentage of physicians who reported a preventive service as very important. The exception was for screening for illicit drug use; more than half of physicians (317/604; 52%, 95% CI 49, 56) thought this screening is very important despite insufficient evidence for USPSTF to recommend it; and despite a USPSTF recommendation against the practice of screening at age 30 years for testicular cancer, 42% (95% CI 38, 46; 252/603) of physicians reported that this screening is very important.

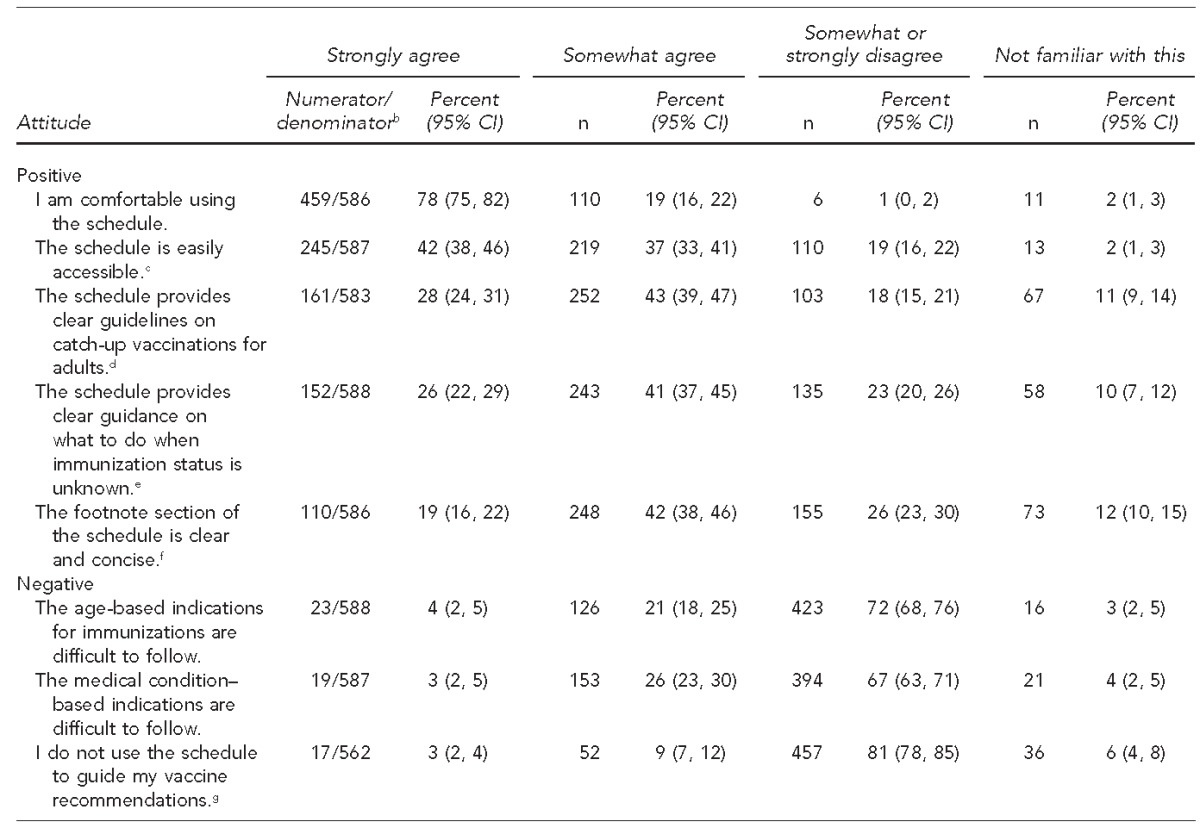

Most physicians reported using the adult immunization schedule to guide vaccine recommendations (Table 3). Most physicians agreed they are comfortable using the schedule to determine which vaccines an adult needs, but 149 of 588 physicians (25%, 95% CI 22, 29) agreed the age-based indications for immunizations are difficult to follow, and 172 of 587 physicians (29%, 95% CI 26, 33) agreed the medical condition–based indications are difficult to follow. General internists were less likely than family physicians to report that the schedule provides clear guidance on what to do with catch-up vaccines, with 61% (95% CI 56, 66; 204/334) of general internists and 84% (95% CI 79, 88; 209/249) of family physicians strongly or somewhat agreeing that guidance is clear (p<0.001). When vaccination status is unknown, 63% (95% CI 57, 68; 212/339) of general internists and 73% (95% CI 68, 79; 183/249) of family physicians strongly or somewhat agreed that guidance is clear (p=0.005). General internists (186/336; 55%, 95% CI 50, 61) were less likely than family physicians (172/250; 69%, 95% CI 63, 74) to strongly or somewhat agree that the footnote section of the schedule is clear (p=0.001). General internists were also more likely than family physicians to disagree that the schedule was easily accessible; 24% (95% CI 19, 28; 80/337) of general internists and 12% (95% CI 8, 16; 30/250) of family physicians strongly or somewhat disagreed (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Physicians' attitudes toward the adult immunization schedule in a study of general internists' and family physicians' (n=588) attitudes toward adult vaccines and other preventive practices, United States, 2012a

Some row percentages do not total to 100 because of rounding.

bDenominator applies to entire row.

cFamily physicians were more likely than general internists to strongly agree that the schedule is easily accessible (50% vs. 36%, p<0.001).

dGeneral internists were less familiar than family physicians with guidelines on catch-up vaccinations (17% vs. 4%, p<0.001).

eGeneral internists were less familiar than family physicians with guidance on what to do when immunization status is unknown (13% vs. 5%, p<0.001).

fGeneral internists were less familiar than family physicians with the footnote section (19% vs. 4%, p<0.001).

gFamily physicians were more likely than general internists to strongly or somewhat disagree with the statement (90% vs. 75%, p<0.001).

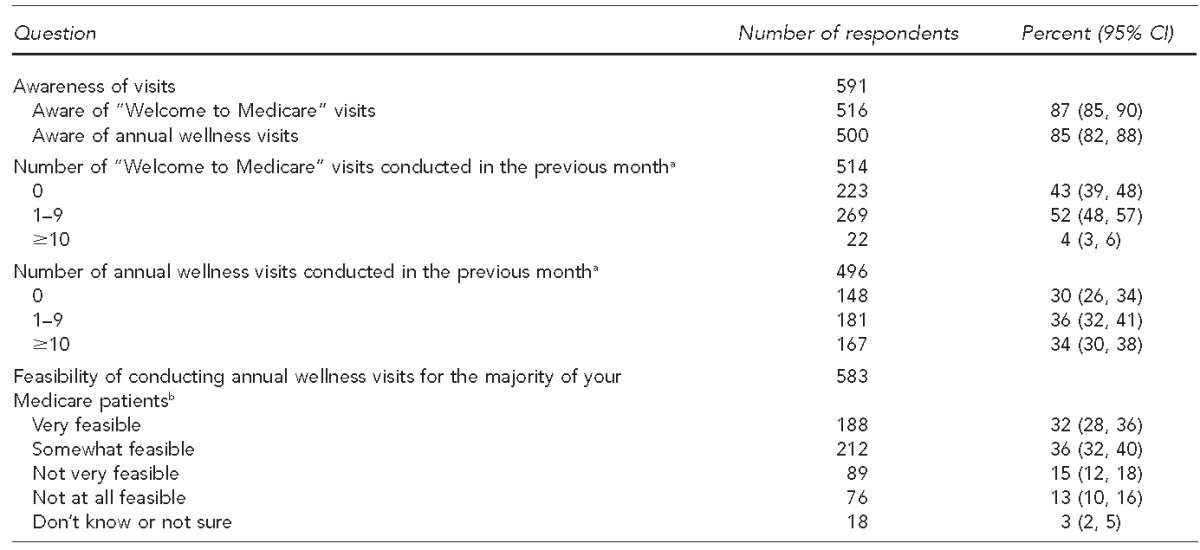

Eighty-seven percent of physicians surveyed were aware of Welcome to Medicare visits (Table 4). Among the 516 of 591 (87%) physicians aware of Welcome to Medicare visits and 500 of 591 (85%) aware of annual wellness visits, 492 of 514 (96%, 95% CI 94, 97) and 329 of 496 (66%, 95% CI 62, 70), respectively, reported having conducted fewer than 10 such visits in the previous month. We found significant differences by percentage of Medicare patients in the physician's practice. Among physicians whose patient population was 25% or more Medicare (329/556; 59%, 95% CI 55, 63), 93% (95% CI 90, 96; 300/321) were aware of the Welcome to Medicare visit (vs. 82%, 95% CI 77, 87; 183/223 among physicians whose patient population was <25% -Medicare; p<0.001), and 88% (95% CI 84, 91; 283/321) were aware of the annual wellness visit (vs. 82%, 95% CI 76, 86; 182/223 among physicians whose patient population was <25% Medicare; p=0.03). Physicians with 25% or more Medicare patients reported conducting more Welcome to Medicare visits: 61% (95% CI 55, 66; 182/300) of physicians with 25% or more Medicare patients reported at least one Welcome to Medicare visit within the previous month (vs. 51%, 95% CI 43, 58; 92/182 with <25% Medicare, p=0.03). However, we found no difference by proportion of Medicare patients in conducting annual wellness visits: 69% (95% CI 63, 74; 195/283) of physicians with 25% or more Medicare patients reported one or more annual wellness visits within the previous month (vs. 71%, 95% CI 64, 78; 129/181 with <25% Medicare; p=0.59).

Table 4.

Awareness and use of, and beliefs about, Medicare preventive visits, in a survey of general internists' and family physicians' attitudes toward and use of adult vaccines and other preventive practices, United States, 2012

aAmong physicians aware of these visits

bColumn percentages may not total to 100 because of rounding.

CI = confidence interval

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to compare primary care physicians' perception of importance of preventive services, including vaccinations. A previous study asked physicians to rank preventive services but not vaccinations.29 We found that even though most current adult vaccine recommendations are not prioritized by ACIP, physicians prioritize some vaccines over others and sometimes rank them below other preventive services. In primary care practice, an environment with many competing demands, lower perceived priority of certain vaccines could have implications for vaccine delivery. Attitudes toward the adult immunization schedule were generally favorable, but a substantial minority of physicians found aspects of the schedule unclear. Medicare preventive service visits provide a setting for delivery of preventive services, including vaccination. However, many physicians were unaware of these visits, and physicians who were aware reported conducting them infrequently.

Many factors likely contributed to physicians' perceptions that some vaccines are less important than other preventive services, including evidence supporting the use of the preventive service, access to the service, patient demand for the service, physician experience treating certain diseases, clarity of the guideline recommending the service, and whether or not the service is tracked as a performance measure for the practice. USPSTF and ACIP use different processes to derive recommendations and different categories to describe them. Both organizations use evidence to develop their recommendations; however, ACIP's recommendations, unlike USPSTF's, are not based solely on strength of evidence. ACIP uses the opinions of voting members and other experts to make recommendations when data are absent or inadequate rather than make no recommendation.5

Access to a preventive service relates to insurance coverage and whether or not the service can be provided in the office. By expanding the number of people with health insurance and mandating that certain preventive services be covered without copayments or deductibles for certain health plans, the Affordable Care Act could improve access to preventive services, including vaccines. However, some vaccines not delivered in the office might continue to be viewed as a lower priority by primary care physicians. The lower perceived importance of the Tdap/Td and herpes zoster vaccines for seniors found in this study may reflect the difficulty some physicians have in providing these vaccines to this population because they are covered as a pharmaceutical benefit by Medicare Part D. Some physicians may refer seniors to pharmacies for these vaccines because they are now widely available in those venues. Other studies have highlighted barriers for medical practices in billing for Medicare Part D vaccines.24,30,31 Seasonal influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are covered by Medicare Part B, under which there is no copay for patients; medical providers can more easily bill for these services than for vaccines covered under Medicare Part D.

Other issues likely contribute to the varying attitudes toward the importance of adult vaccines and USPSTF preventive services found in this study. A national study demonstrated that pay for performance is associated with use of clinical practice guidelines.32 Current performance measures focus on seasonal influenza and pneumococcal vaccines,33 possibly explaining the higher perceived importance of these vaccines. Some researchers suggested using composite measures of adult preventive services as a better way to track overall quality of care.34,35 Performance measures that combine end points by including vaccination with other preventive services may be a way to enhance the delivery of preventive services. Also, cost issues may partially explain attitudes; inventory costs are high for herpes zoster vaccine,36 low for seasonal influenza vaccine,36 and low for blood pressure screening.

To promote adult vaccine delivery, the adult immunization schedule should be clear and easily implemented in practice. The adult schedule is complex because several vaccine recommendations are risk-based or require knowledge of vaccination history, which is often not available. More than one-quarter of physicians in our study agreed that the age-based and medical condition–based indications for vaccination were difficult to follow. Although we did not ask about sources of confusion, the medical condition–based indications for pneumococcal 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV-23) is a likely example. This vaccine is recommended for seniors and for younger people with several medical conditions.37 Recently, ACIP updated its recommendations for preventing pneumococcal disease among adults to include a combination of PPSV-23 and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine38,39 but has recommended various intervals for administration based on which vaccine was received first and qualifying condition.40 To help with this problem, CDC created clinical-decision–support resources that vendors can integrate into electronic health records to facilitate reminders about needed vaccines.41 CDC also provides Internet- and smartphone-based applications for adult vaccine schedules for providers.42

For Medicare beneficiaries, both Medicare preventive service visits offer opportunities to assess patients for needed preventive services, including vaccines, and either deliver those services onsite or refer patients to receive those services from other providers. However, our data suggest these visits are not being used regularly. Some physicians may not realize the distinction between these Medicare visits, in which the focus is to perform an evidence-based prevention needs assessment, and annual physical examination visits, for which the evidence in support of their value is lacking. Evidence supports the annual physical as a means to deliver certain preventive services,43 but a recent Cochrane review44 found general health checks among adults are unlikely to reduce morbidity and mortality from disease. Amid controversy, the Society of General Internal Medicine recommended against performing routine general health checks in asymptomatic adults as one of its Choosing Wisely items.45 Additionally, the Medicare annual wellness visit was a relatively new entity when this study was conducted, and physicians may have not had time to start using these types of visits. Lastly, physicians may not know how to incorporate the annual wellness visit into their current practice. If a physician sees a patient regularly for chronic conditions, use of the annual wellness visit may seem inappropriate.

However, given low rates of vaccination among adults and large numbers of adults who are not up-to-date for other preventive services, use of the Medicare preventive services visits for review of preventive services needs and administration or referral for such services could increase receipt of recommended preventive services. Although physicians reported limited use of these visits, most thought it would be feasible to conduct annual wellness visits for most of their patients. To make annual wellness visits for most patients workable, practices will likely need systems to promote use of these visits and education about how to bill for them, particularly when evaluation and management services are furnished simultaneously,46 which could often be the case in an older, potentially more sickly population.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. Although the sample of physicians surveyed was designed to represent ACP and AAFP memberships, the attitudes, experiences, and practices of these physicians may not be generalizable to all physicians who care for adults. In addition, although this survey had a high response rate, nonrespondents may have held different views from respondents. The survey relied on self-report rather than observation. The hypothetical patients were healthy, and responses may have differed had we asked about the importance of vaccines for patients with high-risk conditions. Also, respondents might have ranked vaccines higher on the survey than in actual practice because of social desirability bias.

CONCLUSION

According to data from our survey, and as evidenced by low vaccination rates among U.S. adults, many physicians do not consider vaccines an important priority. The Affordable Care Act provides an opportunity for U.S. medicine to improve receipt rates for all preventive services, vaccine and otherwise.

Footnotes

The human subjects review board at the University of Colorado Denver approved this study as exempt research not requiring written informed consent. This research was funded by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grant #5U48DP001938. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Preventive Services Task Force (US) What is the Task Force and what does it do? [cited 2014 Jul 24] Available from: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/page/basiconecolumn/28.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) [cited 2014 Jul 24] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip.

- 3.Walton LR, Orenstein WA, Pickering LK. The history of the United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Vaccine. 2015;33:405–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith JC, Hinman AR, Pickering LK. History and evolution of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 1964–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(42):955–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JC, Snider DE, Pickering LK. Immunization policy development in the United States: the role of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:45–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed F, Temte JL, Campos-Outcalt D, Schunemann HJ. Methods for developing evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vaccine. 2011;29:9171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pham HH, Schrag D, Hargraves JL, Bach PB. Delivery of preventive services to older adults by primary care physicians. JAMA. 2005;294:473–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coates RJ, Ogden L, Monroe JA, Buehler J, Yoon PW, Collins JL. Conclusions and future directions for periodic reporting on the use of adult clinical preventive services of public health priority—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(Suppl):73–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams WW, Lu PJ, Greby S, Bridges CB, Ahmed F, Liang JL, et al. Noninfluenza vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(4):66–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Flu vax view [cited 2014 Mar 17] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/index.htm.

- 11.Coates RJ, Yoon PW, Zaza S, Ogden L, Thacker SB. Rationale for periodic reporting on the use of adult clinical preventive services of public health priority—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(2):3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2013–14 influenza season [cited 2015 Feb 6] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1314estimates.htm.

- 13.Shaw FE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Rein AS. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: opportunities for prevention and public health. Lancet. 2014;384:75–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119 through 124 Stat. 1025 (2010)

- 15.Fox JB, Shaw FE. Clinical preventive services coverage and the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e7–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (US) The ABCs of providing the annual wellness visit [cited 2014 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-MLN/MLNproducts/downloads/AWV_chart_ICN905706.pdf.

- 17.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (US) Your “Welcome to Medicare” preventive visit [cited 2014 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.medicare.gov/people-like-me/new-to-medicare/welcome-to-medicare-visit.html.

- 18.Abbo ED, Zhang Q, Zelder M, Huang ES. The increasing number of clinical items addressed during the time of adult primary care visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:2058–65. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0805-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:209–14. doi: 10.1370/afm.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Burriss TC, Shanafelt TD. Providing primary care in the United States: the work no one sees. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1420–1. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635–41. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.University of Colorado Children's Outcomes Research. Vaccine Policy Collaborative Initiative. 2014 [cited 2012 Oct 25] Available from: http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/programs/outcomes/childrensoutcomesresearch/vaccinepolicycollaborativeinitiative/pages/default.aspx.

- 23.Crane LA, Daley MF, Barrow J, Babbel C, Stokley S, Dickinson LM, et al. Sentinel physician networks as a technique for rapid immunization policy surveys. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31:43–64. doi: 10.1177/0163278707311872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurley LP, Bridges CB, Harpaz R, Allison MA, O'Leary ST, Crane LA, et al. U.S. physicians' perspective of adult vaccine delivery. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:161. doi: 10.7326/M13-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dillman D. 3rd ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode: surveys, the tailored design method. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atkeson LR, Adams AN, Bryant LA, Zilberman L, Saunders KL. Considering mixed mode surveys for questions in political behavior: using the Internet and mail to get quality data at reasonable costs. Political Behav. 2011;33:161–78. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMahon SR, Iwamoto M, Massoudi MS, Yusuf HR, Stevenson JM, David F, et al. Comparison of e-mail, fax, and postal surveys of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):e299–303. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.e299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Institute, Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2013. SAS®: Version 9.4 for Windows. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornuz J, Ghali WA, Di CD, Pecoud A, Paccaud F. Physicians' attitudes towards prevention: importance of intervention-specific barriers and physicians' health habits. Fam Pract. 2000;17:535–40. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurley LP, Lindley MC, Harpaz R, Stokley S, Daley MF, Crane LA, et al. Barriers to the use of herpes zoster vaccine. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:555–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Government Accountability Office (US) Many factors, including administrative challenges, affect access to Part D vaccinations [cited 2015 Feb 6] Available from: http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-61.

- 32.O'Malley AS, Pham HH, Reschovsky JD. Predictors of the growing influence of clinical practice guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:742–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0155-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) National Quality Measures Clearinghouse [cited 2014 Oct 14] Available from: http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/index.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Shenson D, Adams M, Bolen J. Delivery of preventive services to adults aged 50–64: monitoring performance using a composite measure, 1997–2004. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:733–40. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0555-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shenson D, Bolen J, Adams M. Receipt of preventive services by elders based on composite measures, 1997–2004. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) CDC adult vaccine price list, 2015 [cited 2015 Feb 6] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/awardees/vaccine-management/price-list/#adult.

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Prevention of pneumococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 1997;46(RR-8):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomczyk S, Bennett NM, Stoecker C, Gierke R, Moore MR, Whitney CG, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(37):822–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennett NM, Whitney CG, Moore M, Pilishvili T, Dooling KL. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(40):816–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Pneumococcal ACIP vaccine recommendations. 2014 [cited 2015 Feb 6] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/vacc-specific/pneumo.html.

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Clinical decision support for immunization (CDSi), 2015 [cited 2015 Feb 6] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/cds.html.

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Adult immunization schedules, United States, 2015 [cited 2015 Feb 6] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html#tool.

- 43.Boulware LE, Marinopoulos S, Phillips KA, Hwang CW, Maynor K, Merenstein D, et al. Systematic review: the value of the periodic health evaluation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:289–300. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-4-200702200-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krogsboll LT, Jorgensen KJ, Gronhoj LC, Gotzsche PC. General health checks in adults for reducing morbidity and mortality from disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e7191. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Society of General Internal Medicine. Five things physicians and patients should question, 2013 [cited 2014 Oct 12] Available from: http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/society-of-general-internal-medicine.

- 46.American College of Physicians, Outland B. Accurate coding of the initial preventive physical examination [cited 2014 Oct 14] Available from: www.acpinternist.org/archives/2014/10/coding.htm.