Abstract

Objectives

Falls in the geriatric population are a major public health issue. With the anticipated aging of the population, falls are expected to increase nationally and globally. We estimated the prevalence and determinants of falls in adults aged ≥65 years and calculated the proportion of elderly who fell and made lifestyle changes as a result of professional recommendations.

Methods

We included adults aged ≥65 years from the 2011–2012 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) and categorized them into two groups based on whether or not they had had at least two falls in the previous 12 months. We performed logistic regression analysis adjusted for the complex survey design to determine risk factors for falls and compare the odds of receiving professional recommendations among elderly with vs. without falls.

Results

Of an estimated 4.3 million eligible elderly participants in the CHIS (2011–2012), an estimated 527,340 (12.2%) fell multiple times in the previous 12 months. Of those, 204,890 (38.9%) were told how to avoid falls by a physician and 211,355 (40.1%) received medical treatment, although fewer than 41.0% had made related preventive changes to avoid future falls. Falls were associated with older age, less walking, and poorer physical or mental health. Non-Asians had higher odds of falling compared with Asians (adjusted odds ratio = 1.69, 95% confidence interval 1.16, 2.45). Most participants reported changing medications, home, or daily routines on their own initiative rather than after professional recommendations.

Conclusion

Patients with a history of falls did not consistently receive professional recommendations on fall prevention-related lifestyle or living condition changes. Given the high likelihood of a serious fall, future interventions should focus on involving primary care physicians in active preventive efforts before a fall occurs.

Falls in the geriatric population are a major public health issue. Among adults aged ≥65 years, falls are the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries nationally and globally.1–3 With the elderly population growing steadily, the number of falls is expected to increase.2 Falls can result in injury, hospitalization, disability, reduced quality of life, and mortality. Furthermore, treatment of falls, such as extensive physical therapy or surgery, can be very costly.3–8 In 2013, the estimated direct medical cost of falls in the United States was $34 billion, adjusted for inflation.1,9 Although some fall prevention measures incur a cost, once risk factors are identified, the most cost-effective options can be selected to reduce the risk of falls and their short- and long-term sequelae.10

Several risk factors for falls are described in the literature. Certain sociodemographic characteristics, such as older age, female sex, low socioeconomic status, and poorer living conditions have been positively associated with falls.6,11–13 Certain physical and mental conditions have also been associated with an increased risk for falls in some studies. These factors include preexisting pain, physical strength, obesity, impaired visual and hearing function, and chronic diseases, such as stroke, diabetes, certain neurological disease, cognitive impairment, and urinary incontinence.11–13

Several prevention programs have been designed to reduce the number of falls. Most interventions focused on increasing the use of assistive devices, improving vision and hearing, and changing treatment of medical conditions, such as minimizing polypharmacy or using psychoactive medications.7,12,14,15 Practice guidelines are also available from professional organizations on screening, assessments, and interventions for falls in the elderly.16,17 However, it is unclear if health professionals routinely recommend these preventive measures at the population level or how often patients follow these professional recommendations.18 Elderly people may need to modify their living style and health professionals may need to modify their working style to effectively implement fall prevention. The effective implementation of prevention efforts and related guidelines can be constrained by several barriers, including time, lack of knowledge and skills, complex health and social issues, service organization issues, and finance issues.19 A survey to examine medical care quality for vulnerable community-dwelling elderly patients showed that many older adults were not even asked about falls or mobility problems.20

Thus, despite the availability of preventive interventions, falls in the elderly remain a major public health concern. Additionally, inconsistent evidence exists on the role played by certain risk factors for falls. For example, studies based on national surveys showed contradictory findings for certain sociodemographic and lifestyle-related characteristics, such as sex, body mass index (BMI), and smoking.3,8,12,21

Given the high treatment costs of fall-related injuries, it is critical to identify the major determinants of falls (i.e., modifiable factors that are most commonly and strongly associated with falls in the elderly population). Accurate information on factors associated with falls can then be used to plan more efficient interventions in high-risk population subgroups. Thus, our primary aims were to (1) asses falls distribution and major risk factors, with particular emphasis on modifiable factors; and (2) determine the distribution of prevention efforts among Californian elderly with multiple falls and the proportion of those elderly who made preventive changes because of professional recommendations. Our study allowed us to simultaneously investigate professional recommendations, post-fall behaviors, and risk factors for multiple falls in a representative, population-based sample.

METHODS

Data source

We used data from the 2011–2012 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS).22 Data were collected continuously during a two-year cycle using a population-based random-digit-dial telephone survey. Participants were selected through multistage clustered stratified sampling with oversampling of some racial/ethnic groups. Noninstitutionalized California residents with a landline telephone or cellular telephone were eligible to participate. Additionally, for this study we included only participants aged ≥65 years who had completed the survey without proxy assistance. The interviews were conducted using a computer-assisted telephone interviewing system. The 2011–2012 CHIS data included information related to falls, sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and health behaviors.23

Outcome variables

The dependent variable for our primary aim was falls, which was measured by the question “During the past 12 months, have you fallen to the ground more than once?” We defined “multiple falls” as having fallen at least twice in the past 12 months. Falls were further categorized as serious or non-serious using participants' responses to the question “Did you get any medical care because of those falls?”

The dependent variables for our secondary aim were professional recommendations and post-fall behavioral changes. Participants with multiple falls in the previous 12 months were asked a series of questions to determine if they had made changes to prevent falls. They were asked if they changed medications, started physical therapy or exercise, changed their home, started to use a cane or walker, or changed their daily routine. Participants who had made changes were then asked if they had made those changes because of professional recommendations.

Covariates

We initially selected independent variables if they were available in the dataset and (1) they had been associated with falls in at least one published study (although other studies might have shown different results) or (2) an association with falls was considered biologically plausible.6,13,24 All covariates were self-reported.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Asian and non-Asian, which included Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic African American, or other), poverty level (poor, low, moderate, or high based on federal poverty level), educational attainment (#high school graduate vs. ≥undergraduate degree), and marital status (married or with partner vs. single).

Lifestyle-related characteristics.

The primary exposures of interest were modifiable lifestyle-related factors: BMI, calculated using self-reported height and weight as not obese (<30 kilograms per square meter [kg/m2]) or obese (≥30 kg/m2), smoking status (not current smoker or current smoker), binge drinking (none, <monthly, or ≥monthly), and walking. We calculated walking as the sum of all the time spent walking for transportation or leisure in the previous seven days categorized into three tertiles: none to low (<10 minutes), moderate (10–30 minutes), or high (>30 minutes).

Health status.

Health status-related variables included overall general health, chronic diseases, disability, and psychological distress. We measured overall general health by the question, “Would you say that in general your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” We measured chronic diseases using the same question about four chronic illnesses: “Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes/stroke/hypertension/heart disease?” When participants could answer “borderline” (for diabetes or hypertension questions only), their answers were grouped with negative answers into the “no” category. We also computed comorbidity as the sum of all four chronic diseases, categorized as none, one, or two or more. Participants were considered to have a disability if they reported at least one of the following: any difficulty going outside the home alone; any difficulty dressing, bathing, or getting around inside the home; limitations in one or more basic physical activities; any difficulty learning, remembering, and concentrating; or being blind/deaf or having severe vision/hearing problems. We measured psychological distress by using the Kessler (K6) Scale, which included questions on feeling nervous, hopeless, restless, depressed, worthless, or that everything was an effort in the past 30 days. The K6 scale is scored in the United States from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time) for each question. The possible total score for all six questions combined was 24. We categorized psychological distress as none or mild (K6 <5), moderate (K6 5–12), or serious (K6 >12).25

Statistical analysis

We performed all analyses using SAS® version 9.4.26 We included design variables in the analyses to account for the complex sampling design and to obtain population-level estimates. We used the CHIS-recommended jackknife method (i.e., a resampling method without replacement) to estimate standard errors.27 We calculated frequencies, percentages, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For our primary analysis, we also calculated crude odds ratios (ORs) for the association of each covariate with the main outcome (i.e., falls in the previous 12 months). We then entered covariates associated with the outcome at two-sided a=0.05 in a full logistic regression model. Through a backward elimination process, we obtained a final partially adjusted model, retaining only covariates that resulted in a greater than 10% change in the OR between the outcome and the main modifiable exposures of interest.

RESULTS

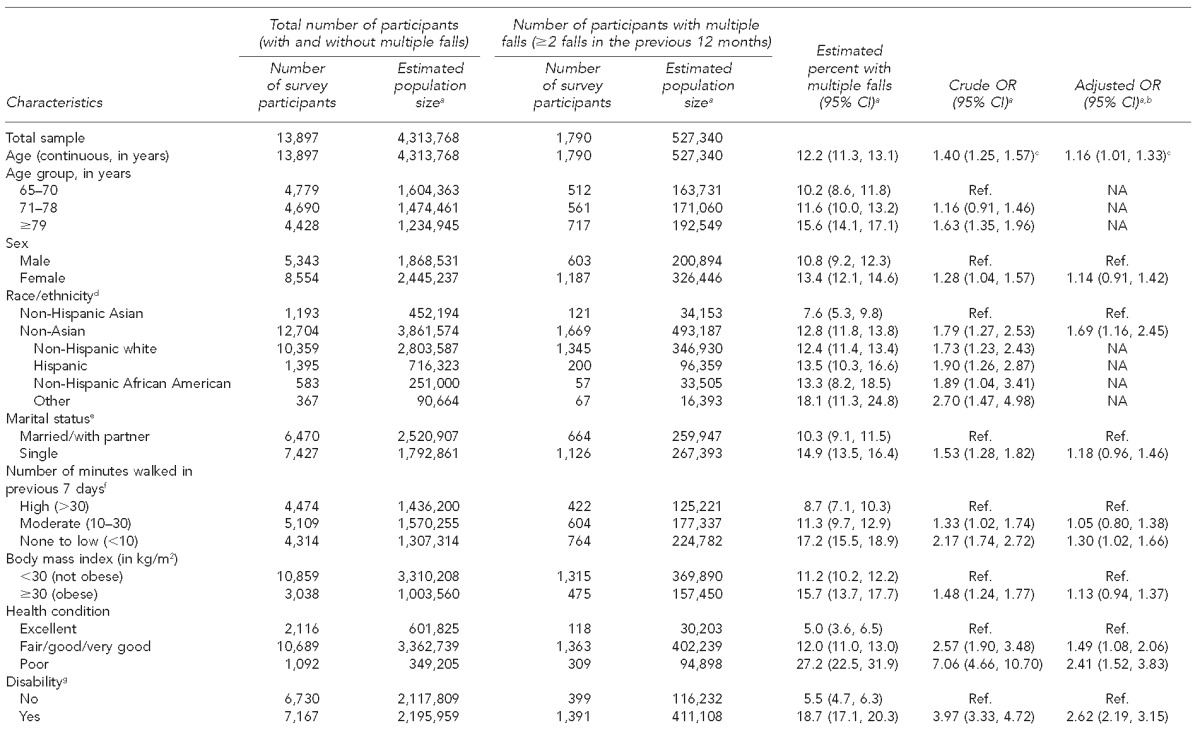

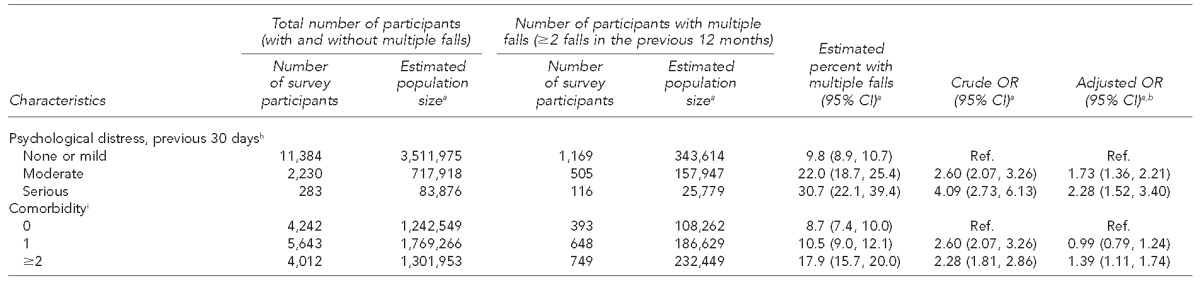

A total of 13,897 surveys were completed by CHIS participants aged ≥65 years, representing an estimated population of approximately 4.3 million elderly adults in California. Overall, an estimated 527,340 of those 4.3 million elderly adults had multiple falls in the previous 12 months, representing an estimated 12.2% (95% CI 11.3, 13.1) of the California elderly population. In both crude and adjusted analyses, falls were less common among non-Hispanic Asians compared with non-Asians. Participants who had walked on average <10 minutes per week had nearly double the odds of having had multiple falls in the previous 12 months compared with those who had walked at least 30 minutes per week. This association persisted even after adjusting for race/ethnicity and other factors. Falls were more common among participants who were older, were in poor health, had moderate or serious psychological distress in the previous 30 days (compared with those with mild or no psychological distress), had at least one disability, or had ≥2 comorbidities (Table 1). Participants with a history of stroke (OR=2.48, 95% CI 1.96, 3.13), heart disease (OR=1.77, 95% CI 1.43, 2.19), hypertension (OR=1.59, 95% CI 1.35, 1.87), or diabetes (OR=1.61, 95% CI 1.31, 1.99) had higher crude prevalence odds ratio of falling compared with participants without these conditions.

Table 1.

Falls prevalence and odds ratios of having multiple falls (≥2 falls in previous 12 months), by sociodemographic and lifestyle-related characteristics and health status, among Californian adults aged ≥65 years, California Health Interview Survey, 2011–2012

aPopulation estimates and 95% CIs are adjusted for the complex design.

bEach variable is adjusted for all other variables listed in the column.

cFor every 10-year unit of age

dIncludes American Indian, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, and ≥2 races

eIncludes widowed, divorced, separated, and never married

fIncludes walking for transportation or leisure

gIncludes any difficulty going outside home alone; any difficulty dressing, bathing, or getting around inside the home; limited to one or more basic physical activities; any difficulty learning, remembering, and concentrating; blind/deaf or has severe vision/hearing problem

hDefined on a Kessler 6 scale as none or mild (<5), moderate (5–12), or serious (>12)

iIncludes heart disease, stroke, hypertension, and diabetes

CI = confidence interval

OR = odds ratio

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

Ref. = reference group

NA = not available

kg/m2 = kilograms per square meter

Participants who were female (vs. male), single (vs. married/with partner), or obese (vs. not obese) had higher crude odds of having a fall. However, after adjusting for other factors in the multivariable logistic model, these characteristics were no longer associated with falls (Table 1). We found no association between poverty level, education, smoking, or alcohol consumption and falls in either crude or adjusted analyses.

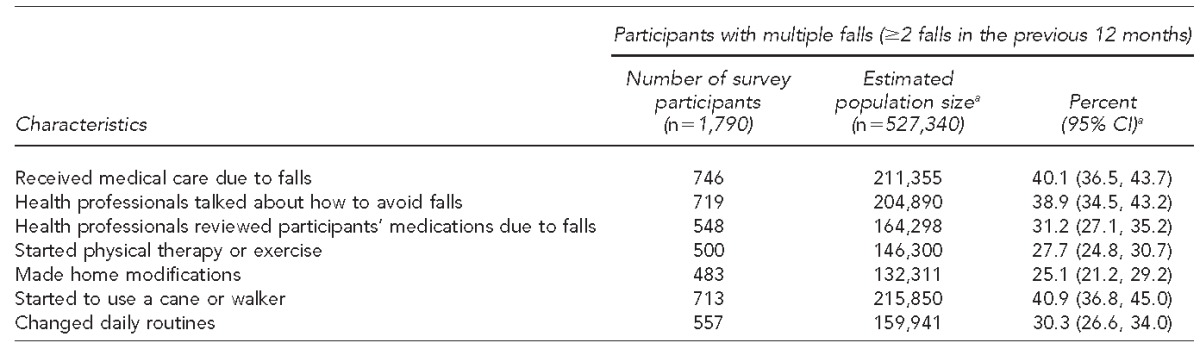

Overall, an estimated 211,355 of 527,340 (40.1%, 95% CI 34.5, 43.7) participants with multiple falls had had a serious fall. An estimated 95,395 of the 211,355 (45.1%, 95% CI 39.3, 51.0) participants with a serious fall reported that health-care professionals did not talk with them about how to avoid falls. An estimated 210,157 of 298,108 (70.5%, 95% CI 65.4, 75.9) elderly participants who had fallen and had seen a medical doctor for non-fall-related reasons were not told how to avoid falls.

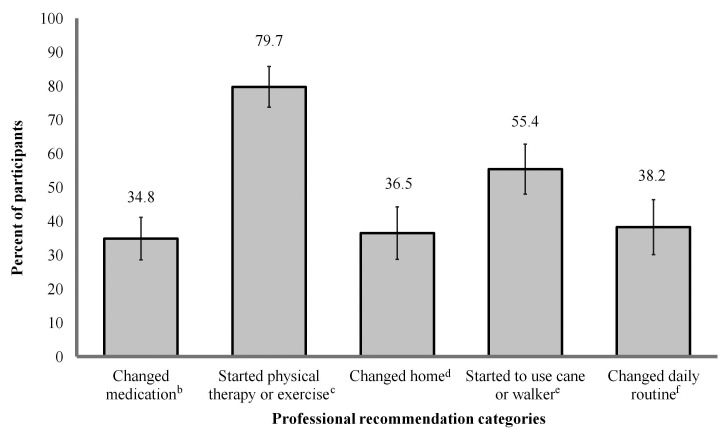

Among 527,340 elderly with multiple falls, some of them had made changes to prevent future falls. The most common change was starting to use a cane or walker (215,850 or 40.9%, 95% CI 36.8, 45.0). Other changes made by fewer than one-third of participants included one or more of the following: health professionals reviewed participants' medications due to falls (164,298, 31.2%, 95% CI 27.1, 35.2), starting physical therapy or exercise (146,300, 27.7%, 95% CI 24.8, 30.7), making changes to their homes (132,311, 25.1%, 95% CI 21.2, 29.2), or changing daily routines (159,941, 30.3%, 95% CI 26.6, 34.0). An estimated 204,890 of 527,340 (38.9%, 95% CI 34.5, 43.2) were told how to avoid falls by a health professional (Table 2). Most participants who started to use a cane or walker or who started physical therapy or exercise did so in response to professional recommendations (Figure). However, fewer than 40% of those who had changed their medications, home, or daily routines were making those changes because of professional recommendations. The remaining participants had made those changes on their own initiative.

Table 2.

Fall treatment and prevention among Californian adults ≥65 years with multiple falls, California Health Interview Survey, 2011–2012

aEstimates and 95% CIs are adjusted for the complex design.

CI = confidence interval

Figure.

Percentage of adults aged ≥65 years who were following professional recommendations when making a change to prevent falls, California Health Interview Survey, 2011–2012a

aError bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

bThe denominator (164,298) is the estimated number of elderly participants with multiple falls who had their medication reviewed by health professionals because of falls. The numerator (57,224) is the estimated number of elderly participants who had their medication changed following a health professional's recommendation.

cThe denominator (146,300) is the estimated number of elderly participants with multiple falls who started physical therapy or exercise. The numerator (116,652) is the estimated number of elderly participants who started physical therapy or exercise because of a health professional's recommendation.

dThe denominator (132,311) is the estimated number of elderly participants with multiple falls who made home modifications. The numerator (48,242) is the estimated number of elderly participants who made home modifications because of a health professional's recommendation.

eThe denominator (215,850) is the estimated number of elderly participants with multiple falls who started to use a cane or walker. The numerator (119,482) is the estimated number of elderly participants who started to use a cane or walker because of a health professional's recommendation.

fThe denominator (159,941) is the estimated number of elderly participants with multiple falls who changed their daily routines. The numerator (61,169) is the estimated number of elderly participants who changed their daily routines because of a health professional's recommendation.

DISCUSSION

Our estimate that 12% of elderly adults in California had multiple falls during a 12-month period was lower than the one reported by the 2006 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), in which 16% of individuals in the United States and 18% of Californians aged ≥65 years reported falling at least once in the previous three months.8 The higher BRFSS percentage was likely due to differences in recall periods and wording of the questions. For example, “coming to rest on a lower level” was considered a fall in the BRFSS, whereas in the CHIS, participants had to reach the ground. Furthermore, participants in the BRFSS (but not the CHIS) with only one fall were considered to have fallen.

One of our study aims was to evaluate determinants of falls. Consistent with previous studies, some risk factors were strongly associated with falls, including older age, less walking, poorer general health condition, presence of certain chronic diseases or disabilities, and more severe psychological distress.6,11–13 Similar to other studies,12,13,28,29 we also found that falls were less common among non-Hispanic Asians, despite their poorer health compared with other races/ethnicities. Among non-Hispanic Asians, only 9.3% reported excellent health (vs. 14.5% of non-Asians), 75.9% reported fair/good/very good health (vs. 78.2% of non-Asians), and 14.8% reported poor health (vs. 7.3% of non-Asians). A potential reason is that Asians tend to have better exercise behaviors, including walking and morning exercises (e.g., older Chinese adults may do Tai-chi).28 Another reason for the racial differences is that Asians may underreport falls,28,29 which might partially explain the lower percentage of Asians who fell even after adjusting for certain physical activities, such as walking.

Crude analyses showed that falls were significantly more common among women, although sex was no longer associated with falls in multivariable analyses. These findings are consistent with those of the 2006 BRFSS.8 However, the 2001–2003 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) reported higher age-adjusted annualized rates of falls among women. The difference between the NHIS and the CHIS and BRFSS is likely related to the fact that the NHIS measured only falls that were serious enough to require medical advice or treatment, and the estimates were adjusted only for age.30 Other community-based studies also found women to be at higher risk for falls than men.6,11

Conflicting evidence in the literature details the association between BMI and falls or fall-related injuries. Higher BMI may result from more adipose tissue or more muscle mass relative to a person's height. A population-based study found that obesity was associated with higher adjusted odds of having a fall in the previous two years,21 although the estimates were not adjusted for physical activity. Given that a potential mechanism for the higher odds of falls is the lower activity level associated with obesity, we included walking activities in the multivariable model and found no association between obesity and falls. The weakening of this association after including walking activities could be explained by exercise being an intermediate variable in the causal pathway between obesity and falls (i.e., obesity could lead to difficulty in mobility, which would lead to reduced strength, physical inactivity, and more falls). The phenomenon of weight gain concurrent with loss of muscle mass (i.e., sarcopenic obesity) is described in the elderly.13,31,32 Underweight participants had similar odds of falling as normal weight participants in crude and adjusted analyses and, for this reason, were grouped together during the analyses.

Overall, 38.9% of participants with multiple falls were told by health professionals how to prevent a fall. Additionally, despite the positive association between lower levels of physical activity and falls in our study and other studies, only 27.7% of participants started physical therapy or exercise after a fall, and 79.7% of them made the change after professional recommendations. These results highlight potential room for improvement in the role that health-care professionals have in guiding patients toward implementation of physical exercise routines for fall prevention. Health-care professionals played a lesser role in other behavioral changes, such as using a cane or changing daily routines, because participants more often made those lifestyle changes spontaneously, regardless of professional recommendations. These results are consistent with those of a previously reported policy brief.33 Future interventions should focus on more active prevention, possibly carried out by a primary care physician during routine medical visits, to increase the number of elderly patients at risk who receive recommendations and reduce the number of subsequent serious and non-serious falls.

Strengths

A major strength of this study was the large population-based sample. Additionally, the complex sampling design and statistical adjustment allowed us to calculate estimates for California. Unlike other national surveys, such as the BRFSS,34 the CHIS included both landline telephone and cellular telephone users. Although data collection had already been completed, several key variables were available to answer the research question and calculate adjusted estimates. Imputation of CHIS data prior to their release minimized missing-data issues, although it did not allow post-release adjustments for the imputation-related error.23

Limitations

The study had some limitations. First, self-reported variables could have introduced recall bias, particularly for questions related to health information and walking experience. Second, the cross-sectional design did not allow us to assess temporal associations. Third, the results may not be generalizable to younger age groups or the entire United States, because data were collected from elderly Californians. Fourth, only individuals with multiple falls (at least two) rather than one fall in the previous 12 months were included. Although this definition tended to increase specificity of this measure, it may also have underestimated the true prevalence of falls in this sample. It also made it difficult to compare the results with those of other studies that used a different definition for falls (e.g., at least one fall).

CONCLUSION

One in eight adults aged ≥65 years in California fell to the ground at least twice in the previous 12 months. With the anticipated aging of the U.S. population, the number of falls and fall-related complications is expected to increase. Accurately identifying high-risk groups and modifiable risk factors for falls is critical for building effective prevention programs. Many falls in the elderly have the potential to be serious; thus, preference should be given to active prevention programs implemented before a fall occurs. In this study, fewer than 41.0% of participants with multiple falls had made changes to prevent future falls, and many of those changes were made spontaneously rather than based on a professional recommendation. Future studies may need to determine whether or not primary care physicians who routinely follow elderly patients could play a more substantial role in informing those patients about prevention strategies before a fall occurs.

Footnotes

This study utilized publicly available, de-identified data and was classified as non-human subjects research by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Important facts about falls [cited 2014 Jun 17] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adultfalls.html.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS”) [cited 2014 Jun 17] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars.

- 3.Lord SR, Sherrington C, Menz HB, Close JC. Epidemiology of falls and fall-related injuries. In: Rubenstein LZ, editor. Falls in older people: risk factors and strategies for prevention. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizzo JA, Baker DI, McAvay G, Tinetti ME. The cost-effectiveness of a multifactorial targeted prevention program for falls among community elderly persons. Med Care. 1996;34:954–69. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR. Falls and their prevention in elderly people: what does the evidence show? Med Clin North Am. 2006;90:807–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1701–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang JT, Morton SC, Rubenstein LZ, Mojica WA, Maglione M, Suttorp MJ, et al. Interventions for the prevention of falls in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 2004;328:680. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens JA, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ, Ballesteros MF. Self-reported falls and fall-related injuries among persons aged ≥65 years—United States, 2006. J Safety Res. 2008;39:345–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis JC, Robertson MC, Ashe MC, Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, Marra CA. International comparison of cost of falls in older adults living in the community: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:1295–306. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frick KD, Kung JY, Parrish JM, Narrett MJ. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of fall prevention programs that reduce fall-related hip fractures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:136–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tromp AM, Pluijm SM, Smit JH, Deeg DJ, Bouter LM, Lips P. Fall-risk screening test: a prospective study on predictors for falls in community-dwelling elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:837–44. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00349-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubenstein LZ. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing. 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii37–41. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mello Ade C, Engstrom EM, Alves LC. Health-related and socio-demographic factors associated with frailty in the elderly: a systematic literature review. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30:1143–68. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00148213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelsey JL, Procter-Gray E, Hannan MT, Li W. Heterogeneity of falls among older adults: implications for public health prevention. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2149–56. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, Claus EB, Garrett P, Gottschalk M, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:821–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society. AGS/BGS clinical practice guideline: prevention of falls in older persons: summary of recommendations [cited 2014 Jun 18] Available from: http://www.americangeriatrics.org/health_care_professionals/clinical_practice/clinical_guidelines_recommendations/prevention_of_falls_summary_of_recommendations.

- 17.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2007. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yardley L, Bishop FL, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen GI, Piot-Ziegler C, et al. Older people's views of falls-prevention interventions in six European countries. Gerontologist. 2006;46:650–60. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tinetti ME, Gordon C, Sogolow E, Lapin P, Bradley EH. Fall-risk evaluation and management: challenges in adopting geriatric care practices. Gerontologist. 2006;46:717–25. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, MacLean CH, Saliba D, Kamberg CJ, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:740–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Himes CL, Reynolds SL. Effect of obesity on falls, injury, and disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:124–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UCLA Center for Health Policy and Research. California Health Interview Survey 2011–2012 public use data files [cited 2014 Jul 10] Available from: http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/data/public-use-data-file/pages/2011-2012.aspx.

- 23.California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2011–2012 methodology report series: report 1—sample design. 2014 [cited 2014 Jun 15] Available from: http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/documents/chis2011-2012_method-1_2014-06-09.pdf.

- 24.Gregg EW, Pereira MA, Caspersen CJ. Physical activity, falls, and fractures among older adults: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:883–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:184–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SAS Institute, Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2013. SAS®: Version 9.4 Procedures Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Efron B, Stein C. The jackknife estimate of variance. Ann Stat. 1981;9:586–96. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwan MM, Close JC, Wong AK, Lord SR. Falls incidence, risk factors, and consequences in Chinese older people: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:536–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicklett EJ, Taylor RJ. Racial/ethnic predictors of falls among older adults: the Health and Retirement Study. J Aging Health. 2014;26:1060–75. doi: 10.1177/0898264314541698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiller JS, Kramarow EA, Dey AN. Fall injury episodes among noninstitutionalized older adults: United States, 2001–2003. Adv Data. 2007;392:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenkins KR. Obesity's effects on the onset of functional impairment among older adults. Gerontologist. 2004;44:206–16. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roubenoff R. Sarcopenic obesity: the confluence of two epidemics. Obes Res. 2004;12:887–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallace SP. More than half a million older Californians fell repeatedly in the past year. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2014:1–7. (PB2014-8) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Bolen J, Stanwyck CA, Mack KA. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Soz Praventivmed. 2001;46(Suppl 1):S3–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]