Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the impact of the Great Recession of 2007–2009 on public health insurance enrollment and expenditures in Alabama. Our analysis was designed to provide a framework for other states to conduct similar analyses to better understand the relationship between macroeconomic conditions and public health insurance costs.

Methods

We analyzed enrollment and claims data from Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in Alabama from 1999 through 2011. We examined the relationship between county-level unemployment rates and enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP, as well as total county-level expenditures in the two programs. We used linear regressions with county fixed effects to estimate the impact of unemployment changes on enrollment and expenditures after controlling for population and programmatic changes in eligibility and cost sharing.

Results

A one-percentage-point increase in a county's unemployment rate was associated with a 4.3% increase in Medicaid enrollment, a 0.9% increase in CHIP enrollment, and an overall increase in public health insurance enrollment of 3.7%. Each percentage-point increase in unemployment was associated with a 6.2% increase in total public health insurance expenditures on children, with Medicaid spending rising by 7.5% and CHIP spending rising by 1.8%. In response to the 6.4 percentage-point increase in the state's unemployment rate during the Great Recession, combined enrollment of children in Alabama's public health insurance programs increased by 24% and total expenditures rose by 40%.

Conclusion

Recessions have a substantial impact on the number of children enrolled in CHIP and Medicaid, and a disproportionate impact on program spending. Programs should be aware of the likely magnitudes of the effects in their budget planning.

The recession that began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009 came to be known as the Great Recession. It increased unemployment rates, decreased household income, and reduced access to employer-sponsored health insurance. Using national survey data, one study found that a one-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate decreased employer-sponsored health insurance coverage by 0.57 percentage points.1 Children's health insurance coverage, however, was largely unaffected because children shifted from private to public coverage. A one-percentage-point increase in unemployment yielded a nearly 1.4 percentage-point increase in the probability that a child was covered by a public health insurance program. Although these estimates are useful, state Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Programs (CHIPs) can better anticipate and budget for changes in enrollment and expenditures by using estimates based on their own programmatic experience.

Little empirical work has examined the effects of macroeconomic conditions on public health insurance enrollment and expenditures. Theory and common sense would suggest that they are counter-cyclical. Simple trends in enrollment and spending reinforce this view. For example, one study that used Current Population Survey data reported that enrollment in employer-sponsored coverage declined by 8.3% from 2007 to 2009, while enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP increased by 6.7%.2 Increases were largest for those with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL).

More rigorous modeling sought to link changes in the macroeconomy with private and public health insurance coverage. Holahan and Garrett used data from the late 1990s to show that a one-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate was associated with an increase in national Medicaid enrollment of 1.5 million.3 Applying their model to the 2007–2009 recession, Holahan estimated that an increase in the unemployment rate from 4.6% to 9.0% would imply an increase in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment of 4.4 million and an increase in total Medicaid and CHIP spending of about $15.2 billion.4 In contrast, Cawley and Simon, using data from the late 1990s, found no significant effects of rising unemployment rates on Medicaid enrollment overall. However, they did find that a one-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate was associated with a 1.04-percentage-point increase in the probability that a child would have Medicaid coverage.5

Only one national study directly examined the effects of the Great Recession on health insurance coverage.1 Using Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data from 2004 through 2010, the study found that a one-percentage-point increase in the state unemployment rate was associated with a 1.67-percentage-point reduction in the probability of having any form of health insurance. The effect was largest for white, college-educated men and older men. In addition, a one-percentage point increase in unemployment was associated with a 1.37-percentage-point increase in the probability that a child would be covered by Medicaid or CHIP. Using a special survey in Ohio, researchers found similar offsetting private and public coverage effects.6 Other researchers constructed a recession index and concluded that the effects on health insurance coverage generally differed across California counties.7 Neither state-specific study, however, provided guidance on the effects of increasing unemployment rates on program participation or spending.

Few studies have examined the effects of recessions on health-care spending. One study found that during 2007–2009, overall growth in health-care spending fell, but Medicare spending growth increased and greater state unemployment rates were associated with increased Medicare spending per beneficiary.8 A one-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate was associated with a 0.7% increase in Medicare per capita spending. Another study found that the proportion of people with high medical costs, defined as more than 10% of family income, was largely unchanged for approximately 19% of the population younger than 65 years of age during the 2007–2009 recession.9 The study concluded that lower family incomes were offset by decreased out-of-pocket spending, largely on prescription drugs.

In this analysis, we used data from a single state, Alabama, to estimate the impact of changes in the unemployment rate on the number of children covered by Medicaid and ALL Kids (the Alabama CHIP) and on the expenditures incurred by each. This approach serves as a simple yet sophisticated method for using state agency data to estimate impacts of the state economy on program use and expenditures. Alabama had one of the largest unemployment-rate increases of any state from 2009 to 2011, but the decline in unemployment after the recession's peak was in the top one-quarter of U.S. states.10 Nonetheless, in 2011, the median county unemployment rate was more than five percentage points above the pre-recession low.

METHODS

We used a simple model of insurance coverage developed by Glied and Jack11 in which coverage is seen as a function of labor market conditions, health-care costs, the structure of the local economy, and the availability of public coverage.

Labor market conditions matter for three fundamental reasons. First, an increase in unemployment means that some people who previously had employer-sponsored health insurance for themselves and their families lose their job and, therefore, lose access to relatively low-cost health insurance. As a result, fewer families have coverage. Second, the loss of a job reduces household income. This loss may decrease the family's demand for health services, as would an income decrease for any normal economic good, which would in turn reduce the demand for health insurance. Finally, a decline in family income associated with job loss may affect eligibility for public coverage, particularly for children. Increased eligibility for public insurance would at least partially mitigate the effects of the loss of employer-sponsored insurance on overall coverage.

Additionally, the availability of public coverage may influence aggregate insurance coverage. State eligibility rules, income thresholds, premium requirements, benefit levels, and access to providers may influence the attractiveness of public programs. A study in 2012 found that increases in eligibility thresholds raised Medicaid and CHIP enrollment rates by 10 to 13 percentage points.12 Other researchers found that even small increases in premium contributions in CHIPs were associated with reductions in enrollment.13,14

This analysis used annual county-level data from a single state from 1999 through 2011. The single-state analysis allows us to ignore state laws, programs, and policies that remain largely in place and unchanged over time. In multistate studies state-specific legal and programmatic differences potentially confound efforts to examine the effects of economic forces. We first summarized data for 1999–2011 and for 2004–2007, four years before the recession, and 2008–2011, four years from its beginning. Then we used “fixed-effects” regression models to estimate the effects of unemployment on the CHIP and Medicaid programs. This statistical approach can be used to control for local economic structure, educational and cultural factors, and the availability and costs of health-care services that may vary significantly across a state but change only slowly in more narrowly defined communities. This approach allowed us to obtain precise estimates of the effect of changes in the local labor market on Medicaid and CHIP enrollment and spending.

The model took the following general form:

where Y represents either enrollment in ALL Kids or Medicaid, or both, by children aged 0–18 years or, analogously, 2012 inflation-adjusted spending, by category, for this age cohort in each program, in county i in year t. The enrollment and spending values were estimated in natural logs. Data were drawn from Alabama ALL Kids and Medicaid enrollment and paid claims files. β, γ, λ, and θ represent parameters to be estimated, and ε was the error term to be minimized.

ALL Kids contracts with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama to provide a network of health-care providers and claims administration; enrollment and claims data were aggregated by calendar year at the county level. Spending categories were defined according to service location (e.g., hospital, emergency department). Alabama Medicaid maintains its own enrollment and claims database, and analogous procedures were followed for these data. Both ALL Kids and Medicaid pay providers on a fee-for-service basis.

UNEMP represents the contemporaneous county unemployment rate provided by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.15 We experimented with a lagged measure of the unemployment rate, which yielded similar values for CHIP but much smaller and often wrong-signed measures for Medicaid. POP represents the total county population in each year drawn from the U.S. Census Bureau.16 POLICY represents a vector of dichotomous variables reflecting policy changes that occurred in each program. TIME was captured as an annual time trend and (time trend)2 to reflect possible nonlinearity in national or statewide trends during the 13-year study period. COUNTY is a vector of county-level fixed effects intended to capture data on county differences that were stable across time. The models were estimated with robust standard errors.

During the study period, children's coverage was not affected by any policy changes in Medicaid. However, two policy changes affected ALL Kids. Before October 2009, public health insurance coverage through ALL Kids was available to children whose family income was greater than the Medicaid eligibility limits up to 200% of the FPL. In October 2009, the income eligibility limit in ALL Kids was raised to 300% of the FPL. For 2010 and 2011, the ALL Kids models included a dichotomous expansion variable with a value of 1. Second, in October 2003, premiums and copays were increased for most participants in ALL Kids. Before this date, enrollees with family incomes of 101%–150% of the FPL paid no premium and those with higher incomes paid a $50 annual premium. Beginning in October 2003, premiums were increased by $50 for each group and copays for selected services were increased by $1 to $10.17 A dichotomous premium variable with a value of 1 after 2003 was included in the ALL Kids models.

During the study period, children may have transitioned between the two public health insurance programs. In a strong economy, family incomes may increase, leading children to move from Medicaid to ALL Kids as they lose Medicaid eligibility but gain ALL Kids eligibility. Analogously, in a recession, children may transition from ALL Kids to Medicaid. In our analysis of program enrollment, we examined the extent to which these transitions occurred by using the person identification codes that are common to ALL Kids and Medicaid.

Because the effects of the recession may have varied among counties, we categorized counties according to their baseline unemployment rate (whether above or below the median unemployment rate in 2007, the first year of the recession) and reran our analysis for each subset.

RESULTS

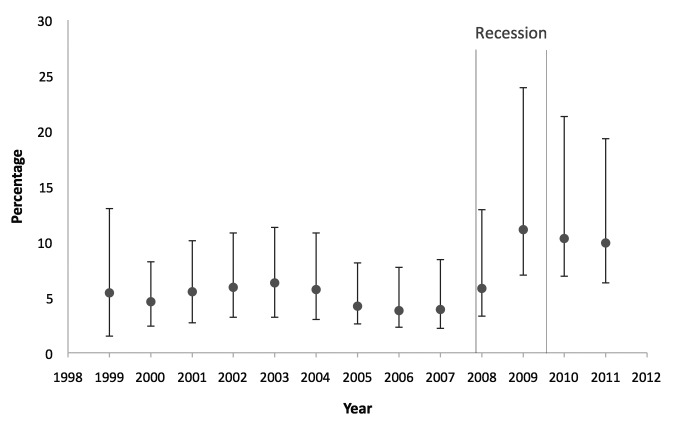

The median county unemployment rate in Alabama was below 4.3% from 2005 through 2007 and then peaked at 11.1% in 2009 (Figure). In 2011, the median unemployment rate was 5.9 percentage points above the rate for 2005–2007. The rates in many counties were much worse than the average rates; unemployment in Wilcox County peaked at 23.9% in 2009. Even the best-performing county in 2011 had a higher unemployment rate than the median county rate in 2005–2007.

Figure.

Median, high, and low annual county unemployment rates in Alabama, by year, 1999–2011a

aData source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (US). Local area employment statistics [cited 2016 Jan 29]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/lau/#tables

Of Alabama's 67 counties, the smallest had approximately 9,000 residents and the largest had more than 650,000 residents. Eleven counties had a population of more than 100,000 people. The statewide annual unemployment rate ranged from 4.1% to 6.4% during much of the 2000s but increased from 4.2% in 2007 to 11.9% in 2009 before declining to 10.5% in 2011. From December 2007 through June 2009, during the recession, the statewide annual unemployment rate increased by 6.4 percentage points. ALL Kids enrollment averaged 881 children per county, ranging from 64 to 10,541 children. Enrollment in Medicaid ranged from 569 to 64,769 children, with a county annual mean of 4,980 children. County-level ALL Kids claims expenditures averaged approximately $1.7 million per year, ranging from $35,000 to more than $24 million. Medicaid spending averaged $5.5 million per year, ranging from $253,000 to nearly $60 million. Approximately 45% of spending was for ambulatory services, with inpatient care and prescription drugs each contributing another 20% (Table 1).

Table 1.

County-level dependent and independent variables used in an analysis of the effects of the Great Recession of 2007–2009 on Medicaid and ALL Kids enrollment expendituresa in Alabama, 1999–2011, 2004–2007, and 2008–2011

Data sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics (US). Local area employment statistics [cited 2016 Jan 29]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/lau/#tables. Census Bureau (US). Population estimates [cited 2016 Jan 29]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/index.html. Unpublished ALL Kids and Alabama Medicaid claims and enrollment files.

bPremium is a dichotomous variable reflecting the years 2004–2011, when ALL Kids participants paid higher premiums and copays.

cExpansion is a dichotomous variable reflecting the years 2010–2011, when eligibility for ALL Kids was expanded to 300% of the federal poverty level.

dAll expenditures are reported in constant 2012 dollars and reflect spending on children.

SD = standard deviation

ALL Kids = Alabama Children's Health Insurance Program

ALL Kids enrollment increased each year, accelerating in 2008, presumably because of the recession, and again in 2009 when eligibility was expanded. In contrast, Medicaid enrollment declined from a high in 2002, returned to this high in 2008, and increased thereafter.

From 1999 to 2011, on average, 9.5% of children transitioned from ALL Kids to Medicaid. The pattern was cyclical, reflecting greater rates of ALL Kids-to-Medicaid transition during the 2001 and 2007 recessions than during other periods. The rate of transition from Medicaid to ALL Kids was much smaller, averaging 2.8% annually and was stable from 2002 to 2011.

A one-percentage-point increase in the county annual unemployment rate was associated with a 0.9% increase in ALL Kids enrollment and a 4.3% increase in children's enrollment in Medicaid (Table 2), yielding a combined increase of 3.7%. The regression analysis suggests that the 6.4-percentage-point increase in the state unemployment rate during the recession led to a 5.8% increase in ALL Kids enrollment, a 27.5% increase in Medicaid enrollment, and a 23.7% increase in combined enrollment.

Table 2.

County-level regression results for the effect of the state unemployment rate and other factors during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 on enrollment of children in ALL Kids and Medicaid, and for both combined, Alabama, 1999–2011a

Dependent variable is the natural logarithm of program enrollment. Regression coefficients represent percentage-point change in enrollment in response to one unit change in explanatory variables. All models include county-level fixed effects and robust standard errors.

bIndicates statistical significance at the 99% confidence level.

cPremium is a dichotomous variable reflecting the years 2004–2011, when ALL Kids participants paid higher premiums and copays.

dExpansion is a dichotomous variable reflecting the years 2010–2011, when eligibility for ALL Kids was expanded to 300% of the federal poverty level.

ALL Kids = Alabama Children's Health Insurance Program

ALL Kids enrollment was also affected by policy changes. Increases in premiums and copays in late 2003 reduced enrollment by an estimated 17.4%. (Parameter estimates of dichotomous variables in a semi-log model such as this cannot be directly interpreted as a unit change. Instead, one must exponentiate the value of the parameter estimate and subtract 1.0. Thus, the natural exponent of the premium estimate of −0.16 in Table 2 is −1.174; subtracting 1.0 yields −0.174, or a 17.4% reduction.18) Expansion of the eligibility threshold for ALL Kids in late 2009 increased enrollment by an estimated 25.9%. In contrast, population changes had modest effects on enrollment; we found a small increasing trend in overall enrollment.

For ALL Kids, a one-percentage-point increase in the average county unemployment rate was associated with a 1.8% increase in total claims expenditures (Table 3). The largest percentage increases in spending were for prescription drugs and dental care, which are perhaps used more discretionarily than other services; emergency department and ambulatory care spending increased more modestly. The increase in inpatient expenditures was on a par with other increases but was not significant. Overall, the 6.4-percentage-point increase in statewide unemployment during the recession increased total ALL Kids paid claims by an estimated 11.3%.

Table 3.

County-level regression results for the effect of the state unemployment rate and other factors during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 on expenditures, in aggregate and by major service category, on children in ALL Kids and Medicaid, and for both combined, Alabama, 1999–2011a

Dependent variable is the natural logarithm of expenditures. Coefficient estimates reflect percentage-point change in expenditures in response to one unit change in explanatory variables. All models include county-level fixed effects and robust standard errors.

bSignificance at 99% confidence level

cPremium is a dichotomous variable reflecting the years 2004–2011, when ALL Kids participants paid higher premiums and copays.

dExpansion is a dichotomous variable reflecting the years 2010–2011, when eligibility for ALL Kids was expanded to 300% of the federal poverty level.

eSignificance at 90% confidence level

fSignificance at 95% confidence level

ALL Kids = Alabama Children's Health Insurance Program

Increases in premiums and copays in late 2003 reduced ALL Kids total claims expenditures by an estimated 29.2% in 2012 dollars. The magnitude of this effect was generally consistent across spending categories, although, again, prescription drug spending was reduced by more—an estimated 52%. These changes in total county-level expenditures were driven primarily by the substantial changes in enrollment. The 2009 expansion in program eligibility increased total claims expenditures by an estimated 24%. The largest percentage increases were in inpatient and prescription drug expenditures.

Medicaid expenditures on children's services increased by 7.5% for each one-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate. However, Medicaid prescription drug expenditures were more responsive than overall expenditures to the unemployment rate; they increased by 16.5% for each percentage-point increase in unemployment. Again, inpatient expenditures increased modestly, but were not significant at the conventional levels.

In our analysis of counties by baseline unemployment rate, we found that increases in enrollment and spending were larger (up to 5–7 times larger) in counties that had lower baseline unemployment rates.

DISCUSSION

This study found that each one-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate at the county level was associated with a 0.9% increase in ALL Kids (i.e., CHIP) enrollment and a 4.3% increase in Medicaid enrollment of children aged 0–18 years. Overall, public insurance enrollment increased by 3.7%, with the smaller combined enrollment change attributable to the transitioning of ALL Kids enrollees to Medicaid coverage during the recession. During the recession, from December 2007 through June 2009, the Alabama unemployment rate increased by 6.4 percentage points. This increase implies that combined public insurance enrollment increased by nearly 24%.

Equally important, program spending on children increased at approximately twice the rate of enrollment. Total public insurance expenditures on children in Alabama increased by 6.2% for each one-percentage point increase in unemployment; ALL Kids spending rose by 1.8% and Medicaid spending rose by 7.5%, implying that combined public insurance expenditures on children rose by 40% during the recession. These increases were largely driven by increases in prescription drug spending and all categories of ambulatory care. Only inpatient spending did not increase significantly. Most of these increases in spending were borne by the federal government; Alabama's matching rate was approximately 78% for ALL Kids and 68% for Medicaid in fiscal year 2012. In states with lower federal match rates, the increases in spending would have greater implications for state budgets.

The effects of the Great Recession were not evenly distributed across the state. Counties that had higher baseline unemployment rates had smaller increases in enrollment and spending as a result of an increase in the unemployment rate than did counties with lower baseline rates. In counties with higher baseline unemployment, those likely to enroll in Medicaid or ALL Kids may have already done so. The increases in unemployment in counties with lower baseline unemployment rates may have disproportionately affected people with fewer resources and less social support.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths and limitations. Public program enrollment and spending is difficult to model.11 States have considerable flexibility in how they implement their Medicaid and CHIP programs, and multistate studies typically struggle to account for the multitude of state-specific economic, social, and political factors that might affect changes in enrollment over time. A single-state study has the advantage of being able to account for state factors. A disadvantage is that single-state results are not necessarily generalizable to other states. However, a single-state approach is relatively easy to implement, and the county-level fixed effects account for the average differences in important but stable characteristics across counties. Our analysis can serve as a model for developing state-specific estimates of the effects of changes in the overall economic environment. One might be concerned about the trends in county characteristics that are accounted for by the fixed-effects model. However, to the extent that these trends are not correlated with the county-specific unemployment rate, no concern is warranted; to the extent that they are, the potential exists for bias of unknown direction.

Another potential limitation was that the unemployment rate is a crude measure of the vitality of the local labor market. One might instead examine an employment rate that accounts for discouraged workers and part-time employment. The distinction between unemployment rate and employment rate is an issue only if the underlying relationship among measured unemployment, worker discouragement, and part-time employment has shifted. Unfortunately, the underlying structure of the U.S. labor market may have changed as a result of the recession.19 If so, our results are probably biased toward zero, because our unemployment values did not adequately capture data on the many new discouraged and part-time workers. That is, if the underlying labor market has changed, higher unemployment today would imply more children eligible for CHIP and Medicaid programs than in the past.

CONCLUSION

We drew two main conclusions. First, as expected, CHIP and Medicaid responded to changes in the local economy. Enrollment increased and spending increased even more, undoubtedly reflecting the adverse selection common to health insurance. The premium and time-cost burdens of enrollment disproportionately lead people who have chronic conditions or who anticipate higher spending to take the trouble to enroll. Providers also have strong incentives to enroll children in CHIP or Medicaid. Thus, people with greater health-care needs may enroll in disproportionate numbers.

Second, the study found substantial effects of modest increases in premiums and copayments on ALL Kids enrollment and even larger effects of the expansion in eligibility. Increasing premiums by $50 per year and copays by $3 to $5 reduced enrollment by more than 17% and spending by more than 29%, suggesting that as state Medicaid and CHIP budgets become tight, even modest increases in out-of-pocket spending can affect program costs. Enrollment and spending was also strongly associated with level of eligibility. The increase in ALL Kids eligibility from 200% to 300% of the FPL increased enrollment by nearly 29% and spending by more than 43%. These increases suggest that children in working poor families have health problems but also that coverage may have shifted from the private sector to the public sector.

Footnotes

This project was funded by a contract from the Alabama Department of Public Health to the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The protocol for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cawley J, Moriya AS, Simon KI. The impact of the macroeconomy on health insurance coverage: evidence from the Great Recession. Health Econ. 2015;24:206–23. doi: 10.1002/hec.3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holahan J. The 2007–09 recession and health insurance coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:145–52. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holahan J, Garrett AB. Washington: Urban Institute; 2001. Rising unemployment and Medicaid. Also available from: http://webarchive.urban.org/uploadedPDF/410306_HPonline_1.pdf [cited 2015 May 8] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holahan J. Menlo Park (CA): The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2009. Rising unemployment, Medicaid and the uninsured. Also available from: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/7850.pdf [cited 2015 May 8] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cawley J, Simon KI. Health insurance coverage and the macroeconomy. J Health Econ. 2005;24:299–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muhlestein D, Seiber E. Children's insurance coverage and crowd-out through the recession: lessons from Ohio. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2021–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charles SA, Snyder S. The recession index: measuring the effects of the Great Recession on health insurance rates and uninsured populations. California J Politics Policy. 2015;7:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McInerney MP, Mellor JM. State unemployment in recessions during 1991–2009 was linked to faster growth in Medicare spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2464–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham PJ. Despite the recession's effects on incomes and jobs, the share of people with high medical costs was mostly unchanged. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2563–70. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.24/7 Wall St. The states that recovered most (and least) from the recession. 2013 Jan 3 [cited 2015 Sep 15] Available from: http://247wallst.com/special-report/2013/01/03/the-states-which-recovered-most-and-least-from-the-recession/3.

- 11.Glied S, Jack K. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2003. Macroeconomic conditions, health care costs, and the distribution of health insurance. Working Paper No. 10029. Also available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w10029 [cited 2015 May 8] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De La Mata D. The effect of Medicaid eligibility on coverage, utilization, and children's health. Health Econ. 2012;21:1061–79. doi: 10.1002/hec.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrisey MA, Blackburn J, Sen B, Becker D, Kilgore ML, Caldwell C, et al. The effects of premium changes on ALL Kids, Alabama's CHIP program. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2:E1–17. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.002.03.a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marton J, Talbert JC. CHIP premiums, health status, and the insurance coverage of children. Inquiry. 2010;47:199–214. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_47.03.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bureau of Labor Statistics (US) Local area employment statistics [cited 2015 Dec 4] Available from: http://www.bls.gov/lau/#tables.

- 16.Census Bureau (US) Population estimates [Alabama counties by year 1999–2011] [cited 2015 Dec 10] Available from: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/index.html.

- 17.Sen B, Blackburn J, Morrisey MA, Kilgore ML, Becker DJ, Caldwell C, et al. Did copayment changes reduce health service utilization among CHIP enrollees? Evidence from Alabama. Health Serv Res. 2012;47:1603–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halvorsen R, Palmquist R. The interpretation of dummy variables in semilogarithmic equations. Am Econ Rev. 1980;70:474–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazear E, Shaw K, Stanton C. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013. Making do with less: working harder during recessions. Working Paper No. 19328. Also available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w19328 [cited 2015 May 8] [Google Scholar]