Abstract

Background

Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with an immune-genetic background. It has been reported as an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD) in the United States and Europe. The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between psoriasis and CHD in a hospital-based population in Japan.

Methods

For 113,065 in-hospital and clinic patients at our institution between January 1, 2011 and January 1, 2013, the diagnostic International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes for CHD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and psoriasis vulgaris were extracted using the medical accounting system and electronic medical record, and were analyzed.

Results

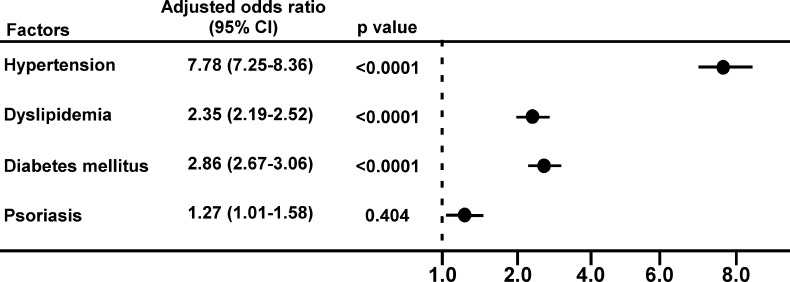

The prevalence of CHD (n = 5,167, 4.5%), hypertension (n = 16,476, 14.5%), dyslipidemia (n = 9,236, 8.1%), diabetes mellitus (n = 11,555, 10.2%), and psoriasis vulgaris (n = 1,197, 1.1%) were identified. The prevalence of CHD in patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and psoriasis vulgaris were 21.3%, 22.2%, 21.1%, and 9.0%, respectively. In 1,197 psoriasis patients, those with CHD were older, more likely to be male, and had more number of the diseases surveyed by ICD-10 codes. Multivariate analysis showed that psoriasis vulgaris was an independent associated factor for CHD (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 1.27; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.01–1.58; p = 0.0404) along with hypertension (adjusted OR: 7.78; 95% CI: 7.25–8.36; p < 0.0001), dyslipidemia (adjusted OR: 2.35; 95% CI: 2.19–2.52; p < 0.0001), and diabetes (adjusted OR: 2.86; 95% CI: 2.67–3.06; p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Psoriasis vulgaris was independently associated with CHD in a hospital-based population in Japan.

Introduction

Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with an immune-genetic background. Although its pathogenesis is not fully understood, there is solid evidence of a susceptibility locus in the human leukocyte antigen region [1, 2]. Genetic polymorphisms in the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene may also contribute to psoriasis and differ between Caucasians and Asians [3]. Psoriasis is common in Caucasians but is rare in Africans [4, 5]. In Asians, psoriasis is less common. The prevalence of psoriasis vulgaris is 0.34% of the general population in Japan [6]. This prevalence is lower than that of the general population in the United States and Europe (2.0–4.0%) [7–9].

Systemic low-grade inflammation may be involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis [10, 11]. Patients with psoriasis vulgaris typically have a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, and obesity compared to those without psoriasis [12]. These comorbidities overlap with the risk factors of coronary heart disease (CHD) [12–15], although the precise mediated mechanisms linking psoriasis and CHD have not been clear.

Many studies in the United States and Europe have shown that psoriasis is an independent risk factor for CHD and cardiovascular events [16–24] or cardiovascular mortality [25]; however, in contrast, other studies concluded that that psoriasis is not an independent risk factor for coronary atherosclerosis and acute cardiovascular events [26–30]. These conflicting results may be because of the differences in the study design, severity of psoriasis, or confounders and effect modifiers, such as psoriatic arthritis [31]. In Japan, the relationship between psoriasis vulgaris and CHD has almost never been studied. One reason for this is the rarity of psoriasis vulgaris in Japanese patients [6]. Considering that an immune-genetic background strongly affects the prevalence of psoriasis and the common underlying causes such as systemic low-grade inflammation, the association between psoriasis and CHD should also be apparent in Japanese patients. The aims of this study were to investigate the relationship between psoriasis vulgaris and CHD in a hospital-based population in Japan.

Methods

Patient population

The medical accounting system and electronic medical record (EMR) data of all clinic and in-hospital patients of all ages at our institution between January 1, 2011 and January 1, 2013 were studied retrospectively. From the EMR data, we extracted patients’ data, including their name, age, and sex by each disease, i.e., psoriasis vulgaris (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10 code L40.0), hypertension (ICD-10 codes I10, I11, I12, I13, I14, and I15), dyslipidemia (ICD-10 code E78), diabetes mellitus (ICD-10 codes E10, E11, E12, E13, and E14), and CHD. CHD included ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction (acute, sub-acute, or old, i.e., ICD-10 codes I21, I22, and I25.2, respectively), and angina pectoris (I20). Each disease was regarded as present when the diagnoses were recorded in the hospital charts. The total number of in-hospital and clinic patients at our institution was determined by the medical accounting system. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Kitano Hospital according to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (P15-06-005). Since this is a retrospective study, the consent was not obtained and patient records/information was anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis.

Statistics

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Mean numbers of risk factors are expressed as the mean and 95% confidence interval (CI). In comparisons of the baseline characteristics of the study population, the chi square test was used for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for continuous variables when appropriate. Differences in categorical variables among two or more groups were analyzed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. Associations between the diseases surveyed and CHD in patients overall were analyzed using a multivariate logistic regression model, which was adjusted for hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and psoriasis. In subgroup analysis of patients who had at least one disease, including CHD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and psoriasis, the association between factors were analyzed by using a multivariate logistic regression model, which was adjusted for hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, psoriasis, and sex as categorical variables and age as a continuous variable. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP software, version 10 (SAS Corp.).

Results

The prevalence of CHD (n = 5,167, 4.2%), hypertension (n = 16,476, 14.5%), dyslipidemia (n = 9,236, 8.1%), diabetes mellitus (n = 11,555, 10.2%), and psoriasis vulgaris (n = 1,197, 1.0%) were identified (Table 1). The prevalence of CHD in patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and psoriasis vulgaris were 21.3% (3,510/16,476), 22.2% (2,056/9,236), 21.1% (2,442/11,555), and 9.0% (108/1197), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Factors related to coronary heart disease (CHD) among the study patients.

| CHD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Present | Absent | ||

| Variables | (n = 113,065) | (n = 5167) | (n = 107,898) | |

| With hypertension | 16,476 (14.5%) | 3,510 (21.3%) | 12,966 (78.7%) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 70.7 (14.3) | 75.6 (11.0) | 69.4 (14.8) | |

| Male (n, %) | 8,642 (52.4%) | 2,165 (61.8%) | 6,477 (49.9%) | |

| With dyslipidemia | 9,236 (8.1%) | 2,056 (22.2%) | 7,180 (77.7%) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 70.0 (3.4) | 75.3 (10.6) | 68.5 (13.7) | |

| Male (n, %) | 4,293 (46.1%) | 1,211 (58.9%) | 3,082 (42.9) | |

| With diabetes mellitus | 11,555 (10.2%) | 2,442 (21.1%) | 9,113 (78.9%) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 69.7 (13.2) | 74.9 (10.3) | 68.3 (13.5) | |

| Male (n, %) | 6,741 (58.3%) | 1,602 (65.6 | 5,139 (56.3) | |

| With psoriasis | 1,197 (1.0%) | 108 (9.0%) | 1,089 (91.0%) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 64.9 (18.1) | 75.0 (12.8) | 63.1 (19.0) | |

| Male (n, %) | 762 (63.6%) | 81 (75.0%) | 681 (62.5%) | |

| With CHD | 5,167 (4.2%) | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 74.0 (12.0) | |||

| Male (n, %) | 3,059 (59.2%) | |||

Regardless of whether patients did or did not have psoriasis, patients with CHD had more number of the three major diseases (hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes) related to CHD than those without CHD (p < 0.001, Table 2). In 1,197 psoriasis patients, those with CHD were older and more likely to be male than those without CHD (p < 0.001), and they had the highest number of the above-mentioned diseases than the other groups (p < 0.001 by the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the characteristics in psoriasis patients with and without CHD.

| With psoriasis | Without psoriasis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD | CHD | |||||||

| Total | Present | Absent | Total | Present | Absent | |||

| Variable | (n = 1,197) | (n = 108) | (n = 1,089) | (n = 111,868) | (n = 5,059) | (n = 106,809) | ||

| Age (y.o., mean, SD) | 64.1 ± 18.9 | 75.0 ± 12.8 | 63.1 ± 19.0 | n/a | 74.0 ± 12.0 | n/a | ||

| Male (n, %) | 762 (63.6%) | 81 (75%) | 681 (62.5%) | n/a | 2978 (58.8%) | n/a | ||

| Hypertension | 288 (24.0%) | 81 (75.0%) | 207 (19.0%) | 16,188 (14.4%) | 3,429 (67.7%) | 12,759 (11.9%) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 231 (19.2%) | 63 (58.3%) | 168 (15.4%) | 9,005 (8.0%) | 1,993 (39.3%) | 7,012 (6.5%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 252 (21.0%) | 60 (55.5%) | 192 (17.6%) | 11,303 (10.1%) | 2,382 (47.0%) | 8,921 (8.3%) | ||

| No. of the three major diseases# | ||||||||

| 3 | 73 (6.1%) | 27 (25.0%) | 46 (4.2%) | 2,883 (2.5%) | 1,066 (21.0%) | 1,817 (1.7%) | ||

| 2 | 173 (14.5%) | 49 (45.4%) | 124 (11.4%) | 7,112 (6.3%) | 1,594 (31.5%) | 5,518 (5.1%) | ||

| 1 | 204 (17.0%) | 25 (23.1%) | 179 (16.5%) | 13,623 (12.1%) | 1,418 (28.0%) | 12,205 (11.4%) | ||

| 0 | 747 (62.3%) | 7 (6.5%) | 740 (68.0%) | 88,250 (78.8%) | 981 (19.3%) | 87,269 (81.7%) | ||

| Mean No. of the disease# (95% CI) | 0.644 (0.590–0.697) | 1.888 (1.725–2.052) | 0.520 (0.469–0.571) | 0.326 (0.322–0.330) | 1.542 (1.524–1.560) | 0.268 (0.264–0.272) | ||

#: hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, CI: confidence interval, n/a: not available.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis after adjusting for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes, and psoriasis, showed that psoriasis vulgaris was still independently associated with CHD (adjusted OR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.01–1.58; p = 0.0404), along with hypertension (adjusted OR: 7.78; 95% CI: 7.25–8.36; p < 0.0001), dyslipidemia (adjusted OR: 2.35; 95% CI: 2.19–2.52; p < 0.0001) and diabetes (adjusted OR: 2.86; 95% CI: 2.67–3.06; p < 0.0001) in an entire hospital-based population (Fig 1). We next assessed 25,799 patients who have at least one disease including CHD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and psoriasis (Table A in S1 File). The psoriasis also shows an independent association with CHD after adjustment for sex and age (Table B in S1 File) in these patients.

Fig 1. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the factors related to coronary heart disease.

Data are adjusted for hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and psoriasis.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we showed the prevalence of psoriasis vulgaris in a hospital-based population in Japan. We also determined that psoriasis vulgaris is independently associated with CHD in these patients.

Psoriasis has been associated with chronic systemic inflammation mediated by the type 1 helper T (Th1) cell [32, 33] and Th17 cell [10, 34, 35]. The Th1 cell stimulates macrophages that secrete tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). Recently, there has been an increasing interest in the Th 17 cell pathway [36] and related pro-inflammatory cytokines in psoriasis, including interleukin (IL)-17 and IL23 [37], which induce the production of inflammatory mediators such as IL1, IL6, IL8, and TNF-α [33]. TNF-α activates endothelium and facilitates leukocyte invasion into surrounding tissues, resulting in the formation of infiltrated plaques, and causes insulin resistance in endothelial cells through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway [38]. Chronic inflammation is associated with insulin resistance, which leads to endothelial dysfunction by disturbing vasodilation through the endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathway [39]. The contribution of genetic polymorphisms to the VEGF gene in psoriasis has also been reported [3]. These data support the association between psoriasis and CHD through chronic low-grade systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction via the overlapping risks for CHD, as also shown in Japanese patients in the present study.

Psoriasis vulgaris has been reported to be independent risk factors for CHD in Europe and United States [16–24]. However, a recently published study by Parisi (2015), including a cohort of 48,523 patients with psoriasis and 208,187 controls and a greater number of predictor variables, did not find an association between psoriasis (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.02, 95%CI: 0.96–1.08) or severe psoriasis (HR:1.29, 95%CI: 0.97–1.70) and the risk for cardiovascular events [30]. In contrast, Dregan et al. (2014), using the same database and inception cohort design, found an independent association between psoriasis and coronary heart disease; their point estimate of the HR of coronary heart disease in severe psoriasis was 1.29 (95% CI: 1.01–1.64, p = 0.042). [23]. Ogdie also reported, using similar database, that the risk of cardiovascular events was higher in patients with psoriasis not prescribed a disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (HR 1.08, 95%CI: 1.02–1.15) and in patients with severe psoriasis (disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug users: HR 1.42, 95%CI: 1.17–1.73) [40]. One reason for these conflicting results may be the inclusion of psoriatic arthritis as an independent confounder in the Parisi study [30,31]. Psoriatic arthritis is associated with psoriasis vulgaris; hence, it can be considered an effect modifying factor that moderates the relationship between psoriasis and outcome [31]. When psoriatic arthritis excluded, the fully adjusted HR of psoriasis and severe psoriasis was 1.46 (95%CI: 1.11–1.92) [30]. A possible association between severe psoriasis and cardiovascular disease was reported by a systematic review of 14 epidemiologic studies [41]. However, whether cardiovascular disease is directly associated with psoriasis remains uncertain, as many of these studies, as well as our present study, could not exclude the possibility of inadequate adjustment for risk factors [41].

Another reason for this inconsistency may be the study design (inception or prevalent cohort). An inception cohort fully captures risk in case of early disease-related outcomes. However, in the setting of psoriasis and CV risk, disease duration (and thus long-term exposure to inflammation) is related to the outcome, with increased risk of the poor outcome as the duration increases. [17]. Thus, use of an inception cohort with short-term follow-up will result in underestimation of the true effect. The prevalent cohort, in contrast, better represents psoriasis patients in the general population. Prevalent designs, however, also have limitations. [31]. The prevalent designs may lead to underestimation of the effect through exclusion of outcomes related to mortality (as in the cases of death from cardiovascular events). [23,40]. Our study design is cross-sectional with one time-point observation. The cardiovascular outcomes were not evaluated but the presence of CHD was assessed with psoriasis in the present study; hence we only addressed the independent association (adjusted OR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.01–1.58; p = 0.0404).

There have been reports that the long-term use of anti-hypertensive drugs and hypertension itself are possibly associated with the development of psoriasis vulgaris [15,39,42]. Dyslipidemia has been also closely associated with psoriasis [43], although the mechanism of connections between psoriasis vulgaris and dyslipidemia is not clear. In another report which analyzed Japanese psoriasis patients, the prevalence of hyperlipidemia and hypertension ranged from 16.7% to 20.7% and from 22.8 to 28.5%, respectively [6], which is consistent with the prevalence in our analysis (Table 2). Table 3 shows the ORs of CHD reported previously in general or hospital-based population in Japan and other countries [17, 44–46]. ORs for CHD in this study were comparable for diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia but seemed to be high for hypertension compared to those of the general population. The prevalence of CHD in patients with psoriasis was 9% (95% CI: 7.38–10.62) in the present analysis. The prevalence of CHD in the entire hospital-based population was 4.5% (95%CI: 4.44–4.69) in the present analysis, whereas the prevalence of CHD in general population estimated by the government data was 0.71% (95%CI: 95%CI: 0.66–0.76) which is calculated from the estimated total numbers of CHD patients (911,000) and the estimated numbers of total population (127, 435,000) in Japan [47]. Thus, several sort of bias may exist in the hospital-based population in the present study. Although further population-based studies are required for generalization, we showed that psoriasis vulgaris is an independent associated factor for having CHD in the entire hospital-based population in the present study (Fig 1) and in patients with one or more disease codes surveyed after adjustment of age and sex (Table B in S1 File).

Table 3. Reported odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) of risk factors for coronary heart disease.

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Population | Hypertension | Dyslipidemia | Diabetes mellitus |

| Kawano H[44] | Hospital based population (Japan) | 4.8 (3.8–5.95) | 1.28 (1.00–1.62) | 3.44 (2.50–4.75) |

| Iso H[45] | General population (male, Japan) | 2.1 (1.1–3.8) | 2.5 (1.5–4.3) | 1.0 (0.5–0.9) |

| Iso H[45] | General population (female, Japan) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 1.8 (0.9–3.4) | 0.5 (0.1–2.1) |

| Armstrong AW[17] | Hospital based population (US) | 1.55 (1.36–1.77) | 1.87 (1.66–2.12) | 1.63 (1.42–1.88) |

| Medrano MJ[46] | General population (Spain) | 1.24 (0.88–1.73) | 1.97 (1.42–2.73) | 1.52 (1.0–2.33) |

| Shiba M (this study) | Hospital based population (Japan) | 7.78 (7.25–8.36) | 2.35 (2.19–2.52) | 2.86 (2.67–3.06) |

Study Limitations

There were several limitations in the study. First, our study did not consider patients’ smoking status or blood tests. Smoking is a risk factor of psoriasis vulgaris [13]. Smoking may affect both CHD and psoriasis. Therefore, smoking would be an important factor. However, it was difficult to determine the smoking habits of all psoriasis patients because the EMR data were retrospective and disease-specific. In addition, since the data of the EMR of the total patients (113,065) was too large to be processed and the total number of patients was collected from the medical accounting system instead, the age and sex of the entire cohort were unknown. It is possible that other unknown confounding factors, including body weight and genetic backgrounds, affected the result. Lack of these data might lead to an inadequate adjustment. In addition, our study population did not represent the general Japanese population. Second, diagnostic codes consistent with the diseases may have included registered codes acceptable to the Japanese health care insurance system. There is a possibility that we overestimated or underestimated the prevalence of these diseases. Third, our study did not demonstrate a temporal relationship or dose-responsiveness. Finally, the CI of psoriasis was relatively broad (95%CI: 1.01–1.58). Therefore, we could not conclude that psoriasis is a risk factor of CHD. Patients with a longer duration of psoriasis vulgaris (defined as >8 years) tended to have CHD [17]. Psoriasis disease characteristics and medications may also impact the clinical outcome of CHD in those with psoriasis [10, 48]. Substantial undertreatment of coronary risk factors is noted in patients with severe psoriasis by Danish nationwide registry [49]. It is controversial whether biological drugs for psoriasis vulgaris, e.g., TNF-α inhibitors and IL12/23 inhibitors, reduce the risk for cardiovascular events [50–52]. Further population-based studies that consider psoriasis characteristics/treatment, age, sex, smoking, etc. are required to generalize and verify that psoriasis is an independent risk factor for CHD in the Japanese population.

Conclusion

Psoriasis vulgaris was independently associated with CHD in a hospital-based population in Japan.

Supporting Information

Characteristics (Table A) and a multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table B).

(DOCX)

Data Availability

The data set is available from the Tazuke Kofukai Medical Research Institute Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Requests to access the data set should be sent to the corresponding author, Takao Kato, at tkato75@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1.Okada Y, Han B, Tsoi LC, Stuart PE, Ellinghaus E, Tejasvi T, et al. Fine mapping major histocompatibility complex associations in psoriasis and its clinical subtypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;95: 162–172. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Wei S, Yang S, Wang Z, Zhang A, He P, et al. HLA-DQA1 and DQB1 alleles are associated with genetic susceptibility to psoriasis vulgaris in Chinese Han. Int. J. Dermatol. 2004;43: 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qi M, Huang X, Zhou L, Zhang J . Four polymorphisms of VEGF (+405C>G, -460T>C, -2578C>A, and -1154G>A) in susceptibility to psoriasis: a meta-analysis. DNA Cell Biol. 2014;33: 234–244. 10.1089/dna.2013.2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzmán-Sánchez DA, Camacho F. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers’ survey. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11: 478–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014;70: 512–516. 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubota K, Kamijima Y, Sato T, Ooba N, Koide D, Iizuka H, et al. Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open. 2015;5: e006450 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelfand JM, Weinstein R, Porter SB, Neimann AL, Berlin JA, Margolis DJ. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom—a population-based study. Arch. Dermatol. 2005;141: 1537–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults—results from NHANES 2003–2004, J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009;60: 218–224. 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis—a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2013;133: 377–385. 10.1038/jid.2012.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tablazon IL, Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, Feldman SR. Risk of cardiovascular disorders in psoriasis patients: current and future. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2013;14: 1–7. 10.1007/s40257-012-0005-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pietrzak A, Bartosińska J, Chodorowska G, Szepietowski JC, Paluszkiewicz P, Schwartz RA. Cardiovascular aspects of psoriasis: an updated review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2013;52: 153–162. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maradit-Kremers H, Dierkhising RA, Crowson CS, Icen M, Ernste FC, McEvoy MT. Risk and predictors of cardiovascular disease in psoriasis: a population-based study. Int. J. Dermatol. 2013;52: 32–40. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05430.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huerta C, Rivero E, Rodríguez LA. Incidence and risk factors for psoriasis in the general population. Arch. Dermatol. 2007;143: 1559–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Setty AR, Curhan G, Choi HK. Obesity, waist circumference, weight change, and the risk of psoriasis in women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167: 1670–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu S, Han J, Li WQ, Qureshi AA. Hypertension, antihypertensive medication use, and risk of psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150: 957–963. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.9957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296: 1735–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Ledo L, Rogers JH, Armstrong EJ. Coronary artery disease in patients with psoriasis referred for coronary angiography. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012;109: 976–980. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahiques-Santos L, Soriano-Navarro CJ, Perez-Pastor G, Tomas-Cabedo G, Pitarch-Bort G, Valcuende-Cavero F. Psoriasis and ischemic coronary artery disease. Actas. Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106: 112–116. 10.1016/j.ad.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, Ochsendorf FR, Zollner TM, Thaci D, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156: 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Jørgensen CH, Lindhardsen J, Charlot M, Olesen JB, et al. Psoriasis and risk of atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke: a Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33: 2054–2064. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Lindhardsen J, Charlot MG, Jørgensen CH, Olesen JB, et al. Psoriasis carries an increased risk of venous thromboembolism: a Danish nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6: e18125 10.1371/journal.pone.0018125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Charlot M, Jørgensen CH, Lindhardsen J, Olesen JB, et al. Psoriasis is associated with clinically significant cardiovascular risk: a Danish nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. 2011;270: 147–157. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dregan A, Charlton J, Chowienczyk P, Gulliford MC. Chronic inflammatory disorders and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and stroke: a population-based cohort study. Circulation. 2014;130: 837–844. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159: 895–902. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31: 1000–1006. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brauchli YB, Jick SS, Miret M, Meier CR. Psoriasis and risk of incident myocardial infarction, stroke or transient ischaemic attack: an inception cohort study with a nested case-control analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160: 1048–1056. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09020.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakkee M, Herings RM, Nijsten T. Psoriasis may not be an independent risk factor for acute ischemic heart disease hospitalizations: results of a large population-based Dutch cohort. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130: 962–967. 10.1038/jid.2009.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stern RS, Huibregtse A. Very severe psoriasis is associated with increased noncardiovascular mortality but not with increased cardiovascular risk. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131: 1159–1166 10.1038/jid.2010.399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowlatshahi EA, Kavousi M, Nijsten T, Ikram MA, Hofman A, Franco OH, et al. Psoriasis is not associated with atherosclerosis and incident cardiovascular events: the Rotterdam Study. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133: 2347–2354. 10.1038/jid.2013.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parisi R, Rutter MK, Lunt M, Young HS, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al. Psoriasis and the Risk of Major Cardiovascular Events: Cohort Study Using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135: 2189–2197. 10.1038/jid.2015.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogdie A, Troxel AB, Mehta NN, Gelfand JM. Psoriasis and Cardiovascular Risk: Strength in Numbers Part 3. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135: 2148–2450. 10.1038/jid.2015.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jain S, Kaur IR, Das S, Bhattacharya SN, Singh A. T helper 1 to T helper 2 shift in cytokine expression: an autoregulatory process in superantigen-associated psoriasis progression? J. Med. Microbiol. 2009;58: 180–184. 10.1099/jmm.0.003939-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nickoloff BJ, Nestle FO. Recent insights into the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis provide new therapeutic opportunities. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113: 1664–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattozzi C, Salvi M, D'Epiro S, Giancristoforo S, Macaluso L, Luci C, et al. Importance of regulatory T cells in the pathogenesis of psoriasis: review of the literature, Dermatology. 2013;227: 134–145. 10.1159/000353398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mudigonda P, Mudigonda T, Feneran AN, Alamdari HS, Sandoval L, Feldman SR. Interleukin-23 and interleukin-17: importance in pathogenesis and therapy of psoriasis. Dermatol. Online J. 2012;18: 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furuhashi T, Saito C, Torii K, Nishida E, Yamazaki S, Morita A. Photo(chemo)therapy reduces circulating Th17 cells and restores circulating regulatory T cells in psoriasis. PLoS One. 2013;8: e54895 10.1371/journal.pone.0054895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Meglio P, Di Cesare A, Laggner U, Chu CC, Napolitano L, Villanova F, et al. The IL23R R381Q gene variant protects against immune-mediated diseases by impairing IL-23-induced Th17 effector response in humans. PLoS One. 2011;6: e17160 10.1371/journal.pone.0017160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li G, Barrett EJ, Barrett MO, Cao W, Liu Z. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces insulin resistance in endothelial cells via a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. Endocrinology. 2007;148: 3356–3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boehncke WH, Boehncke S. Cardiovascular mortality in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, pathomechanisms, therapeutic implications, and perspectives. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2012;14: 343–348. 10.1007/s11926-012-0260-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, Love TJ, Maliha S, Jiang Y, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015b;74: 326–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samarasekera EJ, Neilson JM, Warren RB, Parnham J, Smith CH. Incidence of cardiovascular disease in individuals with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133: 2340–2346. 10.1038/jid.2013.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen AD, Kagen M, Friger M, Halevy S. Calcium channel blockers intake and psoriasis: a case-control study. Acta. Derm. Venereol. 2001;81: 347–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salihbegovic EM, Hadzigrahic N, Suljagic E, Kurtalic N, Hadzic J, Zejcirovic A,et al. Psoriasis and dyslipidemia. Mater. Sociomed. 2015;27: 15–17. 10.5455/msm.2014.27.15-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawano H, Soejima H, Kojima S, Kitagawa A, Ogawa H; Japanese Acute Coronary Syndrome Study (JACSS) Investigators. Sex differences of risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Japanese patients. Circ J 2006;70: 513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iso H, Sato S, Kitamura A, Imano H, Kiyama M, Yamagishi K, et al. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke among Japanese men and women. Stroke 2007;38: 1744–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medrano MJ, Pastor-Barriuso R, Boix R, del Barrio JL, Damián J, Alvarez R, et al. Coronary disease risk attributable to cardiovascular risk factors in the Spanish population. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2007;60: 1250–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Data Source of the National Health and Nutrition Survey. Available at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/kanja/02/index.html (in Japanese)

- 48.Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur. Heart J. 2010;31: 1000–1006. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahlehoff O, Skov L, Gislason G, Lindhardsen J, Kristensen SL, Iversen L, et al. Pharmacological undertreatment of coronary risk factors in patients with psoriasis: observational study of the Danish nationwide registries. PLoS One. 2012;74: e36342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahlehoff O, Skov L, Gislason G, Gniadecki R, Iversen L, Bryld LE, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes and systemic anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with severe psoriasis: 5-year follow-up of a Danish nationwide cohort. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015;29: 1128–1134. 10.1111/jdv.12768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryan C, Leonardi CL, Krueger JG, Kimball AB, Strober BE, Gordon KB, et al. Association between biologic therapies for chronic plaque psoriasis and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306: 864–871. 10.1001/jama.2011.1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tzellos T, Kyrgidis A, Zouboulis CC. Re-evaluation of the risk for major adverse cardiovascular events in patients treated with anti-IL-12/23 biological agents for chronic plaque psoriasis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2013;27: 622–627. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04500.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characteristics (Table A) and a multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table B).

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

The data set is available from the Tazuke Kofukai Medical Research Institute Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Requests to access the data set should be sent to the corresponding author, Takao Kato, at tkato75@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.