Abstract

Drawing from a theory of bicultural family functioning two models were tested to examine the longitudinal effects of acculturation-related variables on adolescent health risk behaviors and depressive symptoms (HRB/DS) mediated by caregiver and adolescent reports of family functioning. One model examined the effects of caregiver-adolescent acculturation discrepancies in relation to family functioning and HRB/DS. A second model examined the individual effects of caregiver and adolescent acculturation components in relation to family functioning and HRB/DS. A sample of 302 recently immigrated Hispanic caregiver-child dyads completed measures of Hispanic and U.S. cultural practices, values, and identities at baseline (predictors); measures of family cohesion, family communications, and family involvement six months post-baseline (mediators); and only adolescents completed measures of smoking, binge drinking, inconsistent condom use, and depressive symptoms one year post-baseline (outcomes). Measures of family cohesion, family communications, and family involvement were used to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis to estimate the fit of a latent construct for family functioning. Key findings indicate that (a) adolescent acculturation components drove the effect of caregiver-adolescent acculturation discrepancies in relation to family functioning, (b) higher levels of adolescent family functioning were associated with less HRB/DS, whereas higher levels of caregiver family functioning were associated with more adolescent HRB/DS, (c) and only adolescent reports of family functioning mediated the effects of acculturation components and caregiver-adolescent acculturation discrepancies on HRB/DS.

Keywords: acculturation, family functioning, substance use, sexual behavior, depressive symptoms

Hispanic youth, especially in middle adolescence, have disproportionately higher rates of some health risk behaviors and depressive symptomology (HRB/DS). Compared to Whites and African Americans, Hispanic adolescents have the highest rates of tobacco use, underage drinking, and unprotected sex (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2014). Similarly, Hispanic adolescents report elevated symptoms of depression compared to other ethnic groups (CDC, 2014). As such, the aim of the present study was to test a culturally relevant model to examine possible determinants of HRB/DS among Hispanics in middle adolescence.

Operationalization of Acculturation

It has been proposed that acculturation may play an important role in understanding disparities in HRB/DS among Hispanics (Abraído-Lanza, Armbrister, Flórez, & Aguirre, 2006). Contemporary theories posit that acculturation is a bidimensional process whereby individuals acquire the practices, values, and identity associated with the receiving (e.g., United States) culture while maintaining the practices, values, and identity associated with the heritage (e.g., Hispanic) culture (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). In addition, each cultural dimension (e.g., acquisition of the receiving culture and maintenance of the heritage culture) has been shown to encompass at least three domains – practices, values, and identity (Schwartz et al., 2010). Prior literature has indicated that domains within each cultural dimension are interrelated, but the rate of acculturation can vary across domains (Schwartz et al., 2010). Thus, levels of acculturation in one domain do not necessarily translate to equal levels in other domains (Cano & Castillo, 2010).

Cultural practices often consist of behaviors such as language use, media preferences, and choice of friends (Schwartz et al., 2010). Cultural values can pertain to the importance placed on the individual in relation to the group. Since the United States is among the more individualistic countries in the world, while many Latin American countries are more strongly collectivist (Hofstede, 2001), the individualism-collectivism dynamic may function as indictors of cultural values for the acculturation process among Hispanics (Schwartz et al., 2010). Cultural identity refers to a subjective sense of solidarity with one’s heritage group and/or with the country in which one resides (Schildkraut, 2011).

Accordingly, at least six acculturation components can be derived by crossing acculturation dimensions (U.S.-culture acquisition and heritage culture retention) and domains (practices, values, and identities); for instance, (a) U.S. practices, (b) Hispanic practices, (c) individualist values, (d) collectivist values, (e) U.S. identity, and (f) Hispanic identity (Schwartz, Unger, et al., 2010).

Acculturation, Health Risk Behaviors, and Depressive Symptoms

Numerous studies, most of which have been cross-sectional, have examined the direct links of individual acculturation components with health risk behaviors, such as substance use and sexual behavior, and with symptoms of depression. Most studies in this area indicate that higher U.S. acculturation is associated with increased health risk behaviors and poor mental health outcomes (Abraído-Lanza, Chao, & Florez, 2005). For example, among U.S. Hispanic adolescent samples consisting of both immigrant and U.S.-born individuals, acculturation has been associated with more tobacco use (Castro, Stein, & Bentler, 2009), alcohol consumption (Guilamo-Ramos, Jaccard, Johansson, & Turrisi, 2004), sexual risk behavior (Afable-Munsuz & Brindis, 2006), and depressive symptoms (Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2011).

One longitudinal study that used a bidimensional and multi-domain model of acculturation to predict substance use and sexual behavior among Hispanic adolescents found that becoming oriented toward U.S. culture was predictive of increased health risk behavior, especially among boys (Schwartz et al., 2013). However, that study did not examine mediators of acculturation and health risk behaviors. To identify pathways between acculturation and health risk behaviors, as well as mental health, more theory driven studies with longitudinal designs are needed to examine potential mechanisms that link acculturation and HRB/DS.

Family Functioning

One mechanism that may link acculturation and HRB/DS is family functioning. The reason for this is that family is the bedrock of child and adolescent development – children and adolescents are socialized primarily within the family, and although adolescents begin to spend more time with peers, family influences remain strong (Cox, Burr, Blow, & Parra Cardona, 2011). Family functioning is a multifaceted construct that encompasses involvement, communication, cohesion, and other positive relational processes within the family (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1997). Family functioning has been shown to protect against substance use (Guilamo-Ramos, Jaccard, Dittus, & Bouris, 2006; Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2009), sexual risk behavior (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006), and depressive symptoms (Gonzales, Deardorff, Formoso, Barr, & Barrera, 2006). Intervention studies have also demonstrated that promoting family functioning can lead to decreases in these negative outcomes (Perrino et al., 2015; Prado & Pantin, 2011).

The theory of bicultural family functioning (Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1993) has been applied to research among Hispanic families, and sets a framework that links acculturation and health through family functioning. This theory proposes that among some Hispanic immigrant families, children and adolescents are likely to acquire the U.S. culture faster – and to a greater degree – than parents, and in some cases youth may begin to lose touch with their heritage culture that remains extremely important to their parents. Consequently, the differential rate of acculturation may create a cultural chasm in the family, which may decrease levels of family functioning, and in turn, increase the likelihood among adolescents to engage in health risk behaviors.

Indeed, longitudinal studies (Smokowski, Rose, & Bacallao, 2008; Unger et al., 2009) have found that parent-child discrepancies in U.S. practices (i.e., adolescent more highly U.S.-acculturated than parents are) are predictive of lower levels of family functioning and of higher probability of past-month alcohol and tobacco use at subsequent points in time. Conversely, parent–child discrepancies in Hispanic practices (i.e., adolescent less Hispanic-oriented than parents) was not associated with family functioning, but was directly associated with a lower probability of substance use.

It should be noted that other research studies have indicated that compared to parent-child acculturation discrepancies, individual measures of adolescent and parent acculturation may serve as stronger predictors of family functioning and health-related outcomes among Hispanic adolescents (Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000). For instance, instead of examining to parent-child acculturation discrepancies, Schwartz et al. (2013) used individual child and parent acculturation trajectories to examine associations with family functioning (measured with indicators of parental involvement, positive parenting, and parent–adolescent communication) and health risk behaviors. Findings indicated that adolescents who were high on U.S. practices, but low on Hispanic practices, reported lower levels of family functioning over time. In turn, higher levels of adolescent family functioning predicted less alcohol use and unexpectedly predicted more cigarette smoking and sexual activity. Parents’ trajectories of acculturation were not predictive of the parents’ perception of family functioning; and parent reports of family functioning were predictive of less adolescent cigarette smoking and sexual activity. These studies underscore the complexity of these relationships, and thus the importance of measuring and examining both adolescent and parent acculturation components and perceptions of family processes, as a way of deriving a family-systems perspective on acculturation and other cultural processes.

The Present Study

The present study aimed to identify the role of perceived family functioning in explaining the effects of acculturation on health risk behaviors and depressive symptoms. Extant literature on acculturation, family functioning, and adolescent health has focused primarily on cultural practices. In this study, we examined longitudinal effects among multiple caregiver-adolescent acculturation discrepancies and individual caregiver and adolescent acculturation components in relation to (a) caregiver and adolescent reports of family functioning and (b) adolescents’ reports of HRB/DS. Using a bidimensional and multi-domain model of acculturation along with the theory of bicultural family functioning, we examined the extent to which family functioning may have mediated the over-time effects of caregiver and adolescent acculturation discrepancies and acculturation components on adolescent substance use, sexual behavior, and depressive symptoms.

To date, a majority of the research in this area has examined the effects of acculturation in samples that collapse across first-generation and later-generation immigrant adolescents. However, recently-immigrated adolescents may differ from longer-term and second-generation immigrant adolescents, and are a particularly important population, because they are likely to be undergoing faster acculturative change and are still able to acquire a second cultural stream (Cheung, Chudek, & Heine, 2010). Conversely, immigrants who arrived at older ages (such as parents) may adapt to a lesser degree than adolescents, especially if they did not attend school in the receiving society (Schwartz, Pantin, Sullivan, Prado, & Szapocznik, 2006). Based on the literature reviewed, we proposed the following hypotheses.

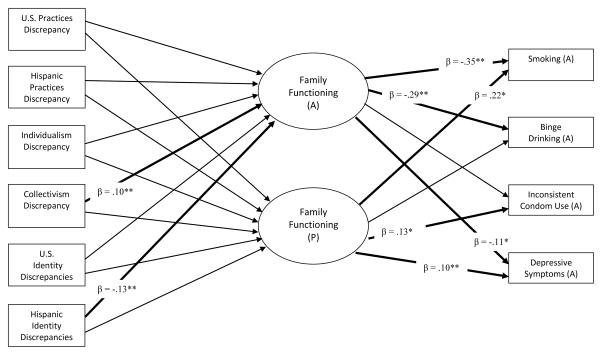

Model 1 (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model 1 with caregiver-adolescent discrepancies.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, A = Adolescent; P = Parent; Direct and indirect effects from acculturation discrepancies on outcomes are not shown to visually simplify the model.

Hypothesis one, greater caregiver-adolescent acculturation discrepancies (across all U.S. and Hispanic domains) would be associated with lower perceptions of family functioning. Hypothesis two, higher levels of caregiver and adolescent family functioning would be associated with lower levels of HRB/DS. Hypothesis three, greater caregiver-adolescent acculturation discrepancies would be associated with higher levels of HRB/DS. Hypothesis four, caregiver and adolescent reports of family functioning would mediate the effects of caregiver-adolescent discrepancies on adolescents’ HRB/DS.

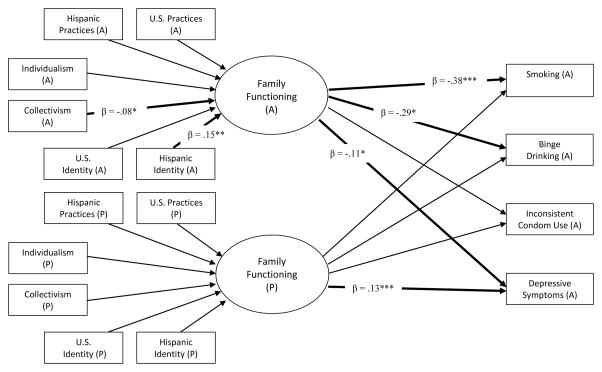

Model 2 (see Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model 2 with adolescent and caregiver acculturation main effects.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, A = Adolescent; P = Parent; Direct and indirect effects from acculturation components on outcomes are not shown to visually simplify the model.

Hypothesis one, higher caregiver and adolescent U.S. acculturation (e.g., practices, values, and identities) would be associated with lower perceptions of family functioning; and higher caregiver and adolescent Hispanic acculturation (across all domains) would be associated with higher perceptions of family functioning. Hypothesis two, higher levels of caregiver and adolescent family functioning would be associated with lower levels of HRB/DS. Hypothesis three, higher caregiver and adolescent U.S. acculturation (across all domains) would be associated with higher levels of HRB/DS, and higher caregiver and adolescent Hispanic acculturation (across all domains) would be associated with lower levels of HRB/DS. Hypothesis four, adolescent and caregiver reports of family functioning would mediate the respective effects of adolescent and caregiver acculturation components on adolescents’ HRB/DS.

Method

Participants

The present study used the first three time points from a larger longitudinal cohort study of acculturation, family functioning, and health risk behavior among recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents and their families (Schwartz, Unger, et al., 2014). Participants included 302 Hispanic caregiver-adolescent dyads from Los Angeles (n = 150) and Miami (n = 152). In all participating families, the target adolescent had been in the United States for five years or less at baseline. Assessment batteries were competed at baseline (May to November 2010 – Time 1), six months post-baseline (February to June 2011 – Time 2), and one-year post-baseline (September to December 2011 – Time 3).

Procedure

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Miami, the University of Southern California, and by the Research Review Committees for each of the school districts that participated in the study. Families were recruited from 23 randomly selected schools (10 in Miami-Dade County and 13 in Los Angeles County) where the student body was at least 75% Hispanic. We selected heavily Hispanic schools because recent Hispanic immigrants tend to settle in ethnically dense areas (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006). After permission was obtained from the principal or vice-principal at each participating school, study staff conducted brief presentations in English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes, where most new immigrant students would be placed, and asked interested students to provide their caregiver’s phone numbers. Prospective participants in Los Angeles County were also recruited from the general student body because students in California are transferred out of ESOL after one year. Some principals in Los Angeles also provided a list of students who had resided in the U.S. for 5 years or less. During the initial visit with each family, the caregiver was asked to provide informed consent for her/himself and the adolescent to participate, and adolescents were asked to provide informed assent.

During this visit, the caregiver and adolescent also completed the baseline assessment battery in English or Spanish, according to their respective preferences. All caregivers in Los Angeles and Miami completed baseline assessments in Spanish, among adolescents in Los Angeles 71% of baseline assessments were completed in Spanish and 96% of baseline assessments in Miami were completed in Spanish. Parent and adolescent assessments were conducted in separate rooms using an audio computer-assisted interviewing (A-CASI) system (Turner et al., 1998). The same procedures were followed at the six-month and one-year follow-ups. For their participation, caregivers received $40 at baseline, and payments increased by $5 at each successive assessment. Each adolescent received a voucher for a movie ticket at each assessment. Six-month retention rates in Miami and Los Angeles were 96% and 88%, respectively. One-year retention rates in Miami and Los Angles were 92% and 77%, respectively. Additional details concerning the study procedures can be found in Schwartz, Unger, et al. (2014).

Measures

Acculturation Components

Both adolescents and caregivers completed measures assessing each of the acculturation components. U.S. and Hispanic cultural practices were measured using the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire-Short Version (BIQ-S; Guo, Suarez-Morales, & Szapocznik, 2009). The BIQ consists of 12 items assessing U.S. practices (e.g., speaking English, eating U.S. foods) and 12 items assessing Hispanic practices (e.g., speaking Spanish, eating Hispanic foods). Responses for all items were provided on a 5-point Likert-type scale, higher scores respectively indicated a higher levels of U.S. and Hispanic cultural practices. Alpha coefficients for U.S. practices among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .89% and .92%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for Hispanic practices among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .85% and .90%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for U.S. practices among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .85% and .93%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for Hispanic practices among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .82% and .87%, respectively.

Cultural values were measured with eight items assessing individualism and eight items assessing collectivism (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). Response choices for all items were on a 5-point Likert Scale, higher scores respectively indicated a higher levels of individualism and collectivism. Alpha coefficients for individualism among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .70% and .74%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for collectivism among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .81% and .73%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for individualism among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .76% and .71%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for collectivism among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .68% and .69%, respectively.

U.S. and Hispanic cultural identities were assessed using the American Identity Measure (AIM; Schwartz, Park, et al., 2012) and the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Roberts et al., 1999). The AIM and the MEIM are parallel in structure and wording, with the only difference being the use of “the United States” versus “my ethnic group.” Responses for all items were on a 5-point Likert Scale, higher scores respectively indicated higher levels of U.S. and Hispanic cultural identities. Alpha coefficients for U.S. cultural identity among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .70% and .74%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for Hispanic cultural identity among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .81% and .73%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for U.S. cultural identity among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .76% and .71%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for Hispanic cultural identity among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .68% and .69%, respectively.

Family Functioning

Both adolescents and caregivers completed measures assessing various domains of family functioning. Family cohesion was measured with the corresponding six-item subscale from the Family Relations Scale (Tolan et., 1997). Responses choices were on a 4-point Likert Scale, higher scores indicated higher levels of family cohesion. Alpha coefficients for family cohesion among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .71% and .81%, respectively. Alpha coefficients among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 2 were .84% and .83%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for family cohesion among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .83% and .69%, respectively. Alpha coefficients among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 2 were .87% and .77%, respectively.

Family communication was measured with the corresponding three-item subscale in the Family Relations Scale (Tolan et., 1997). Responses choices were on a 4-point Likert Scale, higher scores indicated higher levels of family communication. Alpha coefficients for family communication among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .65% and .68%, respectively. Alpha coefficients among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 2 were .73% and .78%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for family communication among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .66% and .57%, respectively. Alpha coefficients among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 2 were .74% and .57%, respectively.

Parental involvement was measured with the corresponding subscale in the Parenting Practices Scale (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Zelli, & Huesmann, 1996). This subscale contains 15 items for adolescents and 20 items for parents. Responses choices were on a 3-point Likert Scale, higher scores indicated higher levels of parental involvement. Alpha coefficients for parental involvement among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .86% and .88%, respectively. Alpha coefficients among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 2 were .88% and .91%, respectively. Alpha coefficients for parental involvement among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 1 were .80% and .82%, respectively. Alpha coefficients among caregivers in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 2 were .89% and .88%, respectively.

Health Risk Behaviors

Substance use was assessed using a modified version of the Monitoring the Future survey (Johnston et al., 2011). Adolescents completed questions regarding frequency of cigarette use and alcohol use behaviors (e.g., binge drinking) in the 90 days prior to assessment. For each substance use behavior, participants typed in the number indicating how many times they had engaged in that behavior during the 90 days prior to assessment. Cigarette smoking and binge drinking were dichotomized because the distributions were highly skewed. Participants were coded regarding whether they reported using (1) or not using (0) in the past 90 days.

Adolescents also completed questions regarding how many times in the last 90 days they had engaged in a number of sexual behaviors, including unprotected sex. Inconsistent condom use was measured as a dichotomous variable: participants were coded regarding whether they reported inconsistent condom use (1) or consistent condom use/abstinence (0) in the past 90 days.

Depressive Symptoms

Symptoms of depression were measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Responses choices were on a 5-point Likert-type scale, higher scores indicated higher levels of depressive symptoms. Alpha coefficients for depressive symptoms among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 2 were .92% and .91%, respectively. Alpha coefficients among adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles at Time 3 were .91% and .94%, respectively.

Analytic Plan

The analytic plan consisted of four steps. First, we computed descriptive statistics for key variables used in the model. Second, we conducted a first-order confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on Mplus v7.2 to estimate the fit of a latent construct for family function for adolescents and caregivers that included indicators of family cohesion, family communication, and parental involvement. Estimating the effect of a latent factor on a dichotomous outcome requires 15 dimensions of mathematical integration per outcome. Therefore, we saved factor scores from the CFAs back to the dataset and used these scores as observed predictors in subsequent analyses. It should be noted that Ram et al. (2005) found that latent variables correlate at .97 with observed scores saved back to the dataset – suggesting a minimal loss of information.

Third, caregiver-adolescent discrepancy scores were computed for each acculturation component using a multilevel algorithm, instead of the subtractive methods (Kim, Chen, Wang, Shen, & Orozco-Lapray, 2013). The multilevel algorithm used an empirical Bayes estimation procedure (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) where parents and adolescents were specified as nested within families; and the discrepancy score for each acculturation component was computed as the latent difference between parent and adolescent scores on that component. This latent difference was computed by weighting one reporter’s score by +.5 and the other reporter’s score by −.5. More information on this method can be found in Kim et al. (2013). For U.S. acculturation components (e.g., U.S. practices, individualism, and U.S. identity), a positive discrepancy score indicated that the adolescent scored higher than the caregiver; and a negative discrepancy scores indicated that adolescent scored lower than the caregiver. Conversely, for Hispanic acculturation components (e.g., Hispanic practices, collectivism, and Hispanic identity), a positive discrepancy score indicated that the caregiver had a higher score than the adolescent; a negative discrepancy score indicated that the caregiver had a lower score than the adolescent.

Fourth, two separate path analysis models using weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) examined the extent to which independent reports of adolescent and caregiver family functioning mediated the effects of (a) caregiver-adolescent acculturation discrepancies and (b) independent adolescent and caregiver acculturation components on HRB/DS. Models estimated with WLSMV that contain categorical outcomes produce standard fit indices using probit regression (Azen & Walker, 2011). Probit regression assumes that the probability of the dependent-variable event occurring is normally distributed; therefore, a standardized probit regression coefficient is comparable to a standardized linear regression coefficient (with the exception that the outcome is the probability of event occurrence). It should be noted that age, study site, gender, years in the U.S., and parental education were included as covariates in both path models.

To examine whether model parameters would differ significantly between gender and study site, we conducted two invariance tests. We compared the fit of a model with all paths and factor loadings free to vary across gender against the fit of a model with all paths and factor loadings constrained equal across gender. The same procedure was performed to test invariance between study sites. A nonsignificant decrement in model fit would indicate that the model should be estimated on the full sample. The invariance tests suggested that the model fit equivalently across gender study site. Therefore, we report results from the model collapsed across gender and study site; and introduced both of these variables as a covariates.

Both the CFA and path analysis models were evaluated using four model fit indices (Kline, 2005; Yu, 2002): (a), chi-square test of model fit (χ2) > .05, (b) comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ .95, (c) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .05, and (d) weighted root mean square residual (WRMR) ≤ 1.0. In evaluating the path analysis models that we tested (Figure 1 and Figure 2), we used a sandwich covariance estimator (Kauermann & Carroll, 2001) to adjust standard errors for the effects of multilevel nesting (families within schools).

The following parameters were estimated in Model 1: (a) effects of Time 1 caregiver-adolescent discrepancies on Time 2 adolescent and caregiver perceptions of family functioning, controlling for Time 1 adolescent and caregiver reports of family functioning; (b) effects of Time 2 adolescent and caregiver reports of family functioning on Time 3 cigarette smoking, binge drinking, inconsistent condom use, and depressive symptoms (where Time 2 levels of depressive symptoms were controlled); and (c) indirect effects of caregiver-adolescent discrepancies on adolescent outcomes via independent adolescent and caregiver reports of family functioning.

Model 2 estimated the following parameters: (a) effects of Time 1 adolescent and caregiver acculturation components on Time 2 adolescent and caregiver perceptions of family functioning, controlling for Time 1 adolescent and caregiver reports of family functioning; (b) effects of Time 2 adolescent and caregiver reports of family functioning on Time 3 cigarette smoking, binge drinking, inconsistent condom use, and depressive symptoms (where Time 2 levels of depressive symptoms were controlled); and (c) indirect effects of adolescent and caregiver acculturation components on adolescent outcomes via independent adolescent and caregiver reports of family functioning.

Neither model controlled for prior levels of cigarette smoking, binge drinking, or inconsistent condom use because they were dichotomous. Scores on dichotomous variables can remain the same over time even though developmental change has occurred (Agresti, 2007). Additionally, controlling for prior levels of categorical variables may, in some cases, result in inflated standard errors for model parameters, potentially rendering baseline-adjusted results unstable or invalid (Glymour, Weuve, Berkman, Kawachi, & Robins, 2005).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations for Time 1 predictor variables and Time 2 mediator variables are provided in Table 1. Frequencies for cigarette smoking, binge drinking, and inconsistent condom use in the past 90 days; as well as means and standard deviations for depressive symptoms at Time 3 are also reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Study Variables

| Variable | Adolescent | Caregiver | Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variables at Time 1 | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| U.S. Practices | 47.59 (16.22) | 30.95 (14.35) | 13.33 (12.83) |

| Hispanic Practices | 56.85 (15.06) | 59.10 (12.11) | −2.03 (10.77) |

| Individualist Values | 19.71 (4.91) | 20.71 (4.61) | −1.03 (6.09) |

| Collectivist Values | 24.45 (4.07) | 24.19 (3.26) | −.24 (4.91) |

| U.S. Identity | 27.05 (8.36) | 28.85 (7.16) | .35 (19.19) |

| Hispanic Identity | 32.04 (7.92) | 33.81 (5.26) | 1.96 (9.34) |

| Mediator Variables 6 Months Post-Baseline | |||

| Family Cohesion | 13.25 (3.47) | 14.55 (2.61) | |

| Family Communication | 50.11 (1279) | 55.60 (9.16) | |

| Parent Involvement | 39.76 (11.26) | 57.37 (8.46) | |

| Outcome Variables 1 Year Post-Baseline | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Substance Use (last 90 days) | |||

| Cigarette Smoking | 16 (5.3%) | - | |

| Binge Drinking | 28 (9.3%) | - | |

| Sexual Behavior (last 90 days) | |||

| Inconsistent Condom Use | 20 (6.6%) | - | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Depressive Symptoms (last 7 days) | 30.71 (13.77) | - | |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

At Time 1, the mean adolescent age was 14.51 years (SD = 0.88 years, range 14 to 17), and 53% of adolescents were boys. Adolescents in Miami had resided in the U.S. for a significantly shorter period of time (Mdn = 1 year, interquartile range = 0–3 years) compared to those in Los Angeles (Mdn = 3 years, interquartile range = 1–4 years), Wilcoxon Z = 6.39, p < .001. The majority of adolescents in Miami had immigrated from Cuba (61%), and the majority of adolescents in Los Angeles had immigrated from Mexico (70%).

Caregivers in the Los Angeles reported living in the United States an average of 4.78 (SD 2.95) years and an average of 2.49 (SD 2.72) years in Miami. In Los Angeles 67% of adolescents and caregivers immigrated together while in Miami 83% of adolescents and caregivers immigrated together. As per caregiver’s self-reports, the mean annual household income in Los Angeles was $34,520 (SD $5,398) and in Miami it was $26,915 (SD $13,438). Participating caregivers were mothers (70%), fathers (25%), stepparents (3%), and grandparents/other relatives (2%). Twenty-seven percent of caregivers reported less than nine years of education, 18% attended high school but did not graduate, 33% completed high school, 12% attended college but did not graduate, and 10% reported having a bachelor’s degree or greater. The mean years of education for caregivers in Los Angeles was 8.84 (SD 4.47) and in Miami it was 11.18 (SD 3.73).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A CFA for adolescent family functioning using data from Time 1 indicated that the standardized factor loadings were acceptable (family cohesion, .79; family communication, .69; parental involvement, .69). The latent factor for adolescent family functioning with Time 2 data indicated that the standardized factor loadings were acceptable (family cohesion, .82; family communication, .76; parental involvement, .83). The χ2 (n = 302, df = 5) = 5.77, p > .05, CFI (.999), and RMSEA (.023) all indicated adequate model fit. The latent factors for adolescent family functioning were invariant across the two time points.

A CFA for caregiver family functioning using data from Time 1 indicated that the standardized factor loadings were acceptable (family cohesion, .81; family communication, .81; parental involvement, .34). The latent factor for caregiver family functioning with Time 2 data indicated that the standardized factor loadings were acceptable (family cohesion, .77; family communication, .81; parental involvement, .31). According to Brown (2006), a standardized factor loadings of .30 or higher are acceptable in questionnaire-based research. The χ2 (n = 302, df = 7) = 8.78, p > .05, CFI (.997), and (RMSEA (.029) all indicated adequate model fit. The latent factors for caregiver family functioning were invariant across the two time points.

Model 1 Results

Most fit indices for Model 1, with the exception of χ2 suggest that the data adequately fit the model: χ2 (n = 268, df = 16) = 26.05, p = .05, CFI (.952), RMSEA (.048), and WRMR (.561). Highlighted below are the effects that were statistically significant.

Acculturation Discrepancies Predicting Family Functioning

Results indicate that caregiver-adolescent discrepancy scores of collectivism (β = .10, p = .01) and Hispanic identity (β = −.13, p < .01) had statistically significant effects on adolescent reports of family functioning.

Conversely, none of the acculturation discrepancy scores had statistically significant effects on caregiver reports of family functioning.

Family Functioning Predicting HRB/DS Outcomes

Results indicate that higher levels of adolescent family functioning had statistically significant effects on smoking (β = −.35, p < .01), binge drinking, (β = −.29, p = .01), and depressive symptoms (β = −.11, p = .02).

In addition, higher levels of caregiver family functioning had statistically significant effects on smoking (β = .21, p = .02), inconsistent condom use (β = .13, p = .03) and depressive symptoms (β = .10, p < .01).

Acculturation Discrepancies Predicting HRB/DS Outcomes

Direct effects between caregiver-adolescent acculturation discrepancies and HRB/DS outcomes indicate that discrepancy scores of American identity had a statistically significant effect on depressive symptoms (β = −.15, p < .01).

Mediation Effects of Family Functioning

Mediation analyses indicate there were some moderate indirect effects. Discrepancy scores of collectivism had an indirect effect on smoking (β = −.03, p = .05), binge drinking (β = −.03, p = .03), and depressive symptoms (β = −.01, p = .01) via adolescent reports of family functioning. Similarly, discrepancy scores of Hispanic identity had an indirect effect on smoking (β = .05, p = .03) and binge drinking (β = .04, p < .01) via adolescent reports of family functioning.

Conversely, none of the other acculturation discrepancy scores had statistically significant indirect effects on HRB/DS outcomes via caregiver reports of family functioning.

Model 2 Results

Fit indices for Model 2 suggest that the data adequately fit the model: χ2 (n = 265, df = 28) = 29.72, p > .05, CFI (.990), RMSEA (.015), and WRMR (.473). Highlighted below are the effect that were statistically significant.

Acculturation Components Predicting Family Functioning

Results indicate that adolescent reports of collectivism (β = −.08, p = .04) and Hispanic identity (β = .15, p < .01) had statistically significant effects on adolescent reports of family functioning.

Conversely, none of the caregiver reports of acculturation components had statistically significant effects on caregiver reports of family functioning.

Family Functioning Predicting HRB/DS Outcomes

Results indicate that higher levels of adolescent family functioning had statistically significant effects on smoking (β = −.37, p < .001), binge drinking, and (β = −.29, p < .05), and depressive symptoms (β = −.11, p = .04).

In addition, higher levels of caregiver family functioning had a statistically significant effect on depressive symptoms (β = .13, p < .001).

Acculturation Components Predicting HRB/DS Outcomes

Direct effects between acculturation components on HRB/DS outcomes indicate that adolescent reports of individualism had a statistically significant effect on smoking (β = .40, p = .04).

No statistically significant effects were found between caregiver reports of acculturation components and HRB/DS.

Mediation Effects of Family Functioning

Again, mediation analyses indicate there were some moderate indirect effects. Adolescent reports of collectivism (β = .03, p = .04) had an indirect effect on smoking via adolescent reports of family functioning. Similarly, adolescent reports of Hispanic identity (β = −.06, p = .01) had an indirect effect on smoking via adolescent reports of family functioning.

No statistically significant indirect effects were found between caregiver reports of acculturation components and HRB/DS.

Discussion

In the current study, we tested two models based on the theory of bicultural family functioning (Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1993). Key findings from this study indicate that (a) compared to caregivers, adolescent acculturation components were stronger predictors of family functioning, and (b) higher levels of adolescent family functioning were associated with less HRB/DS. Below is a brief review of the findings from the two models.

Findings from Model 1 can be summarized as follows. First, adolescents who reported higher levels of collectivism, compared to their caregiver, reported higher levels of family functioning. Conversely, adolescent who reported lower levels of Hispanic identity, compared to their caregiver, reported lower levels of family functioning. With regard to the caregiver reports of family functioning, none of acculturation discrepancies had a statistically significant effect. Second, higher levels of adolescent family functioning were associated with lower levels of smoking, binge drinking, and depressive symptoms. However, higher levels of caregiver family functioning were associated with higher levels of smoking, inconsistent condom use, and depressive symptoms. Third, adolescents who reported higher levels of American identity, compared to their caregiver, reported lower levels of depressive symptoms. Fourth, adolescent reports of family functioning mediated the effect of collectivism discrepancy scores and Hispanic identity discrepancy scores and on HRB/DS. However, no mediation effects were detected via the caregiver reports of family functioning.

Findings from Model 2 indicate higher levels of adolescent collectivism were associated with lower levels of adolescent family functioning. Conversely, higher levels of adolescent Hispanic identity were associated with reports of better family functioning. However, none of the caregiver acculturation components were associated with caregiver reports of family functioning. Second, higher levels of adolescent family functioning were protective against smoking, binge drinking, and depressive symptoms. Conversely, higher levels of caregiver family functioning were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Third, higher levels of adolescent individualism were associated with more smoking. In contrast, none of the caregiver acculturation components had a direct effect on HRB/DS outcomes. Fourth, adolescent reports of family functioning mediated the effect of adolescent collectivism and adolescent Hispanic identity on HRB/DS, whereas no mediation effects were found for caregiver reports family functioning. Lastly, fit indices were slightly better for Model 2; however, the data fit both models adequately.

By examining the effects of acculturation discrepancies and the main effects of acculturation components in relation to family functioning we were able to elucidate that individual levels of adolescent collectivism and Hispanic identity drove the effect of the corresponding caregiver-adolescent discrepancies. Findings suggests that adolescent levels of acculturation components maybe stronger predictors of family functioning compared to caregiver levels of acculturation components.

Although it was expected that collectivism discrepancies would predict lower family functioning; an unexpected result was that higher levels of adolescent collectivism predicted lower levels of family functioning. Our search of the literature did not produce a plausible explanation for this effect; thus, we can only speculate on what may explain this finding. It may be the case that among adolescents in our sample, the hypothesized beneficial effect of collectivism on family functioning may be contingent (e.g., moderated) on the presence of another construct (e.g., perceived parental social support). For example, higher reports of adolescent collectivism may be associated with higher perceptions of family functioning only if the adolescent perceives an adequate level of parental social support.

Findings from this study also suggest that higher levels of adolescent Hispanic identity may lead to more harmonious family relationships, even if the adolescent reports a higher degree of Hispanic identity compared to the caregivers. One explanation may be that Hispanic immigrant adolescents develop a more salient ethnic identity in response to cultural adaptation (e.g., reactive ethnicity; Rumbaut, 2008), and in turn, become more connected to their families to navigate more effectively through this process. This finding is encouraging because some research has suggested that ethnic identity begins to develop during early and middle adolescence (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006). Thus, prevention interventions may be enhanced by including content or exercises that support the exploration of ethnic identity by encouraging adolescents to seek out information about their family heritage and about their family’s reasons for and experiences with immigrating to the United States (Holcomb-McCoy, 2005).

It is worth noting that adolescent reports of Hispanic identity significantly predicted adolescent-reported family functioning, but that no corresponding effect emerged for caregiver reports. A likely explanation is that adolescents spend more time with Americanized peers and interacting with U.S. media than caregivers do. These U.S. social institutions may create pressures for adolescents to Americanize and to drift away from traditional Hispanic practices, values, and identity. Conversely, many Hispanic immigrant caregivers in the Miami and Los Angeles areas reside in ethnically dense enclaves where the majority of their interactions are with other Hispanic people (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006). When adults immigrate to ethnic enclaves, their cultural orientations likely do not change very much over time (Schwartz et al., 2006). Indeed, many Hispanic adults in these enclaves can go about their daily business as though they were still in their countries of origin. Adolescents generally do not have this option, because they attend school courses in English, associate with friends who may be Americanized (even if these friends are ethnically Hispanic), and interact with U.S. media such as websites, social media, and television and radio stations. So the likelihood of adolescents changing their cultural orientations over time are much greater than the corresponding odds for caregivers – and as a result, the chances of an adolescent acculturating in a way that compromises family functioning are far greater than the corresponding chances for a caregiver.

Prior research has indicated that family functioning may reduce HRD/DS among Hispanic adolescents (Gonzales et al., 2006; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006; Perrino et al., 2015; Unger et al., 2009). However, the present study was one of the few to examine the ways in which caregiver and adolescent reports of family functioning may exert different types of effects on adolescent outcomes. In our results, adolescent reports of better family functioning were protective against subsequent HRB/DS; however, higher levels of caregiver family functioning were associated with more HRB/DS. These findings provide increased confidence that the effects of family functioning on HRB/DS are not likely reflective of inflated within-reporter associations, and they also appear consistent with a prior study that found that discrepancies between caregiver and adolescent reports of family processes are predictive of adolescent risk behaviors (Córdova, Huang, Garvey, Estrada, & Prado, 2014). That is, caregiver reports of family functioning can only predict adolescent outcomes – accounting for adolescent-reported outcomes – to the extent to which the two reporters diverge. Such divergence may explain, at least in part, the inconsistent effects of caregiver-reported family functioning on adolescent health-related outcomes.

Results corresponding with acculturation-related variables and HRB/DS indicated that the direct effects of acculturation discrepancies and acculturation components had minimal influence on youth outcomes. These findings support the recommendation to move beyond limited investigation of direct effects of acculturation on health; and instead examine mechanisms that may mediate the effects of acculturation on health (Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Hernandez-Jarvis, 2007). An explanation for the limited direct effects in this sample may be due to the temporal lag between the times at which acculturation-related and HRB/DS variables were measured. One recommendation is that future studies utilize trajectories of acculturation in conjunction with theoretical models of acculturation and health (Castro, 2007; Schwartz et al., 2013).

Finally, our results support the notion that family functioning is a clinically relevant factor in the acculturation-health association and merits consideration in the development and application of prevention interventions (Prado & Pantin, 2011). Evidence-based interventions that are well suited to prevent and reduce HRB/DS among Hispanic adolescents by targeting acculturation and family factors include Familias Unidas (Coatsworth, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2002; Perrino et al., 2015), Bicultural Effectiveness Training (Szapocznik, Rio, Perez-Vidal, Kurtines, Hervis, & Santisteban, 1986), and Entre Dos Mundos (Between Two Worlds; Bacalloa & Smokowski, 2005). It should be noted that many family-based interventions are premised on intervening into parents’ perceptions of family functioning with the goal of changing adolescent behavior; however, some research has indicted that that such parent-centered interventions may be less efficacious with foreign-born adolescents than for their U.S.-born counterparts (Córdova, Huang, Pantin, & Prado, 2012). Our results, as well as those reported by Schwartz et al. (2013) using a different sample, suggest that mediated effects emerged only for adolescent reports of family functioning. Therefore, increasing adolescent involvement in intervention activities may be needed for recent immigrant families.

More research is needed to determine the most effective content for prevention interventions. However, some strategies that may improve family functioning, and in turn reduce HRB/DS, include helping family members become aware of their cultural similarities while encouraging acceptance of some of their cultural differences (Szapocznik et al., 1997). Similarly, helping families reduce intergenerational conflict and develop a shared worldview may promote better family functioning (Bacalloa & Smokowski, 2005; Szapocznik et al., 1986). Lastly, facilitating the development of parental and youth biculturalism and family adaptability may be another effective strategy (Bacalloa & Smokowski, 2005).

Limitations

The present findings should be interpreted in light of several important limitations. A significant majority of the Miami sample was Cuban and a significant majority of the Los Angeles sample was Mexican. The degree to which findings from this study would generalize to other Hispanic nationalities is therefore not known. Similarly, the sample was exclusively comprised of recent-immigrant high school students; thus, it is unknown the degree to which our results generalize to younger adolescents, emerging adults, immigrants who have resided in the United States for a longer period of time, or second-generation immigrants who were born in the United States. Second, both study sites and all schools had a high proportion of Hispanics. Thus, it is plausible that the high density of Hispanics in these social environments slowed the rate of U.S. cultural acquisition and facilitated the retention Hispanic cultural retention for both adolescent and caregivers. Future studies may benefit from multisite designs that include geographic regions and schools with low and high proportions of Hispanics. Lastly, self-report measures are vulnerable to participant misrepresentation or error.

Conclusion

Despite these and other limitations, the current study has presented some advances in testing the theory of bicultural family functioning. Namely, compared to caregivers, adolescents’ acculturation components were stronger predictors of family functioning. Perhaps one of the most important implications of the findings was that higher levels of adolescents’ perceptions of family functioning were associated with less HRB/DS. As such, the development and refinement of prevention interventions may consider targeting adolescents’ experience of family functioning in an effort to reduce HRB/DS.

References

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Flórez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Florez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:1243–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agresti A. An introduction to categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Azen R, Walker CM. Categorical data analysis for the behavioral and social sciences. Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Castillo LG. The role of enculturation and acculturation on Latina college student distress. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education. 2010;9:221–231. doi: 10.1177/1538192710370899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG. Is acculturation really detrimental to health? American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1162. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.116145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Stein JA, Bentler PM. Ethnic pride, traditional family values, and acculturation in early cigarette and alcohol use among Latino adolescents. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:265–292. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0174-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63:1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung BY, Chudek M, Heine SJ. Evidence for a sensitive period for acculturation: Younger immigrants report acculturating at a faster rate. Psychological Science. 2011;22:147–152. doi: 10.1177/0956797610394661. doi:0.1177/0956797610394661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Familias Unidas: A family-centered ecodevelopmental intervention to reduce risk for problem behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5:113–132. doi: 10.1023/a:1015420503275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdova D, Huang S, Pantin H, Prado G. Do the effects of a family intervention on alcohol and drug use vary by nativity status? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:655–660. doi: 10.1037/a0026438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdova D, Huang S, Garvey M, Estrada Y, Prado G. Do parent-adolescent discrepancies in family functioning increase the risk of Hispanic adolescent HIV risk behaviors? Family Process. 2014;53:348–63. doi: 10.1111/famp.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R, Burr B, Blow A, Parra-Cardona JR. Latino adolescent substance use in the United States: Using the bioecodevelopmental model as an organizing framework. Journal of Family Theory and Review. 2011;3:96–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2011.00086.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, Aber JL. The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1–10. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:443–458. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(200007)28:4<443::AID-JCOP6>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Robins JM. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;162:267–278. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Deardorff J, Formoso D, Barr A, Barrera M. Family mediators of the relation between acculturation and adolescent mental health. Family Relations. 2006;55:318–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00405.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, Huesmann LR. The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:115–129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115. [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Johansson M, Tunisi R. Binge drinking among Latino youth: role of acculturation-related variables. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:135–142. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Dittus P, Bouris AM. Parental expertise, trustworthiness, and accessibility: Parent-adolescent communication and adolescent risk behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:1229–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00325.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Suarez-Morales L, Schwartz SJ, Szapocznik J. Some evidence for multidimensional biculturalism: Confirmatory factor analysis and measurement invariance analysis on the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire-Short Version. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:22–31. doi: 10.1037/a0014495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences. 2. London: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb-McCoy C. Ethnic identity development in early adolescence: implications and recommendations for middle school counselors. Professional School Counseling. 2005;9:120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. Volume I: Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kauermann G, Carroll RJ. A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:1387–1396. doi: 10.1198/016214501753382309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Chen Q, Wang Y, Shen Y, Orozco-Lapray D. Longitudinal linkages among parent–child acculturation discrepancy, parenting, parent–child sense of alienation, and adolescent adjustment in Chinese immigrant families. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:900–912. doi: 10.1037/a0029169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Acculturation, gender, depression, and cigarette smoking among US Hispanic youth: the mediating role of perceived discrimination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1519–1533. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9633-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Pantin H, Huang S, Brincks A, Brown CH, Prado G. Reducing the Risk of Internalizing Symptoms among High-risk Hispanic Youth through a Family Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Family Process. 2015 doi: 10.1111/famp.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America: A portrait. 3. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H. Reducing substance use and HIV health disparities among Hispanic youth in the USA: The Familias Unidas program of research. Psychosocial Intervention. 2011;20:63–73. doi: 10.5093/in2011v20n1a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;7:385–401. doi: 10.1177/01466216770010030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Chow SM, Bowles RP, Wang L, Grimm K, Fujita F, Nesselroade JR. Examining interindividual differences in cyclicity of pleasant and unpleasant affects using spectral analysis and item response modeling. Psychometrika. 2005;70:773–790. doi: 10.1007/s11336-001-1270-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero AJ. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:301–322. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Application and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. Reaping what you sow: Immigration, youth, and reactive ethnicity. Applied Developmental Science. 2008;12:108–111. doi: 10.1080/10888690801997341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schildkraut D. National identity in the United States. In: Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, Vignoles VL, editors. Handbook of identity theory and research. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 845–866. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Des Rosiers S, Huang S, Zamboanga BL, Unger JB, Knight GP, Szapocznik J. Developmental trajectories of acculturation in Hispanic adolescents: Associations with family functioning and adolescent risk behavior. Child Development. 2013;84:1355–1372. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Park IJ, Huynh QL, Zamboanga BL, Umana-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, Agocha VB. The American identity measure: Development and validation across ethnic group and immigrant generation. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2012;12:93–128. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2012.668730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Pantin H, Prado G, Sullivan S, Szapocznik J. Family functioning, identity, and problem behavior in Hispanic immigrant early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:392–420. doi: 10.1177/0272431605279843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Pantin H, Sullivan S, Prado G, Szapocznik J. Nativity and years in the receiving culture as markers of acculturation in ethnic enclaves. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2006;37:345–353. doi: 10.1177/0022022106286928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Des Rosiers SE, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Zamboanga BL, Huang S, Szapocznik J. Domains of acculturation and their effects on substance use and sexual behavior in recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Prevention Science. 2014;15:385–396. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0419-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch RS, Hurley EA, Zamboanga BL, Park IJK, Kim SY, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Castillo LG, Brown E, Greene AD. Communalism, familism, and filial piety: Are they birds of a collectivist feather? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:548–560. doi: 10.1037/a0021370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga B, Hernandez-Jarvis L. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines W. Family psychology and cultural diversity: Opportunities for theory, research, and application. American Psychologist. 1993;48:400–407. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.4.400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines W, Santisteban DA, Pantin H, Scopetta M, Mancilla Y, Aisenberg S, McIntosh S, PerezVidal A, Coatsworth JD. The evolution of structural ecosystemic theory for working with Latino families. In: Garcia J, Zea MC, editors. Psychological Interventions and Research with Latino Populations. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1997. pp. 156–180. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Rio A, Perez-Vidal A, Kurtines W, Hervis O, Santisteban D. Bicultural effectiveness training (BET): An experimental test of an intervention modality for families experiencing intergenerational/intercultural conflict. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1986;8:303–330. doi: 10.1177/07399863860084001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Huesmann LR, Zelli A. Assessment of family relationship characteristics: a measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression among urban youth. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:212–223. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, Gelfand MJ. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Parent–child acculturation discrepancies as a risk factor for substance use among Hispanic adolescents in Southern California. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2009;11:149–157. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CY. Doctoral dissertation. University of California; Los Angeles: 2002. Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit indices for latent variable models with binary and continuous outcomes. Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/Yudissertation.pdf. [Google Scholar]