Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a set of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by a deficit in social behaviors and nonverbal interactions such as reduced eye contact, facial expression, and body gestures in the first 3 years of life. It is not a single disorder, and it is broadly considered to be a multi-factorial disorder resulting from genetic and non-genetic risk factors and their interaction. Genetic studies of ASD have identified mutations that interfere with typical neurodevelopment in utero through childhood. These complexes of genes have been involved in synaptogenesis and axon motility. Recent developments in neuroimaging studies have provided many important insights into the pathological changes that occur in the brain of patients with ASD in vivo. Especially, the role of amygdala, a major component of the limbic system and the affective loop of the cortico-striatothalamo-cortical circuit, in cognition and ASD has been proved in numerous neuropathological and neuroimaging studies. Besides the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens is also considered as the key structure which is related with the social reward response in ASD. Although educational and behavioral treatments have been the mainstay of the management of ASD, pharmacological and interventional treatments have also shown some benefit in subjects with ASD. Also, there have been reports about few patients who experienced improvement after deep brain stimulation, one of the interventional treatments. The key architecture of ASD development which could be a target for treatment is still an uncharted territory. Further work is needed to broaden the horizons on the understanding of ASD.

Keywords: Autistic Disorders, Review, Neurobiology, Amygdala

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a set of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by a lack of social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication in the first 3 years of life. The distinctive social behaviors include an avoidance of eye contact, problems with emotional control or understanding the emotions of others, and a markedly restricted range of activities and interests [1]. The current prevalence of ASD in the latest large-scale surveys is about 1%~2% [2,3]. The prevalence of ASD has increased in the past two decades [4]. Although the increase in prevalence is partially the result of changes in DSM diagnostic criteria and younger age of diagnosis, an increase in risk factors cannot be ruled out [5,6]. Studies have shown a male predominance; ASD affects 2~3 times more males than females [2,3,7]. This diagnostic bias towards males might result from under-recognition of females with ASD [8]. Also, some researchers have suggested the possibility that the female-specific protective effects against ASD might exist [9].

A Swiss psychiatrist, Paul Eugen Bleuler used the term "autism" to define the symptoms of schizophrenia for the first time in 1912 [10]. He derived it from the Greek word αὐτὀς (autos), which means self. Hans Asperger adopted Bleuler's terminology "autistic" in its modern sense to describe child psychology in 1938. Afterwards, he reported about four boys who did not mix with their peer group and did not understand the meaning of the terms 'respect' and 'polite', and regard for the authority of an adult. The boys also showed specific unnatural stereotypic movement and habits. Asperger describe this pattern of behaviors as "autistic psychopathy", which is now called as Asperger's Syndrome [11]. The person who first used autism in its modern sense is Leo Kanner. In 1943, he reported about 8 boys and 3 girls who had "an innate inability to form the usual, biologically provided affective contact with people", and introduced the label early infantile autism [12]. Hans Asperger and Leo Kanner have been considered as those who designed the basis of the modern study of autism.

Most recently, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) adopted the term ASD with a dyadic definition of core symptoms: early-onset of difficulties in social interaction and communication, and repetitive, restricted behaviors, interests, or activities [13]. Atypical language development, which had been included into the triad of ASD, is now regarded as a co-occurring condition.

As stated earlier, the development of the brain in individuals with ASD is complex and is mediated by many genetic and environmental factors, and their interactions. Genetic studies of ASD have identified mutations that interfere with typical neurodevelopment in utero through childhood. These complexes of genes have been involved in synaptogenesis and axon motility. Also, the resultant microstructural, macrostructural, and functional abnormalities that emerge during brain development create a pattern of dysfunctional neural networks involved in socioemotional processing. Microstructurally, an altered ratio of short- to long-diameter axons and disorganization of cortical layers are observed. Macrostructurally, MRI studies assessing brain volume in individuals with ASD have consistently shown cortical and subcortical gray matter overgrowth in early brain development. Functionally, resting-state fMRI studies show a narrative of widespread global underconnectivity in socioemotional networks, and task-based fMRI studies show decreased activation of networks involved in socioemotional processing. Moreover, electrophysiological studies demonstrate alterations in both resting-state and stimulus-induced oscillatory activities in patients with ASD [14].

The well-conserved sets of genes and genetic pathways were implicated in ASD, many of which contribute toward the formation, stabilization, and maintenance of functional synapses. Therefore, these genetic aspects coupled with an in-depth phenotypic analysis of the cellular and behavioral characteristics are essential to unraveling the pathogenesis of ASD. The number of genes already discovered in ASD holds the promise to translate the knowledge into designing new therapeutic interventions. Also, the fundamental research using animal models is providing key insights into the various facets of human ASD. However, a better understanding of the genetic, molecular, and circuit level aberrations in ASD is still needed [15].

Neuroimaging studies have provided many important insights into the pathological changes that occur in the brain of patients with ASD in vivo. Importantly, ASD is accompanied by an atypical path of brain maturation, which gives rise to differences in neuroanatomy, functioning, and connectivity. Although considerable progress has been made in the development of animal models and cellular assays, neuroimaging approaches allow us to directly examine the brain in vivo, and to probably facilitate the development of a more personalized approach to the treatment of ASD [16].

Etiology

ASD is not a single disorder. It is now broadly considered to be a multi-factorial disorder resulting from genetic and non-genetic risk factors and their interaction.

Genetic causes including gene defects and chromosomal anomalies have been found in 10%~20% of individuals with ASD [17,18]. Siblings born in families with an ASD subject have a 50 times greater risk of ASD, with a recurrence rate of 5%~8% [19]. The concordance rate reaches up to 82%~92% in monozygotic twins, compared with 1%~10% in dizygotic twins. Genetic studies suggested that single gene mutations alter developmental pathways of neuronal and axonal structures involved in synaptogenesis [20,21,22]. In the cases of related with fragile X syndrome and tuberous sclerosis, hyperexcitability of neocortical circuits caused by alterations in the neocortical excitatory/inhibitory balance and abnormal neural synchronization is thought to be the most probable mechanisms [23,24]. Genome-wide linkage studies suggested linkages on chromosomes 2q, 7q, 15q, and 16p as the location of susceptibility genes, although it has not been fully elucidated [25,26]. These chromosomal abnormalities have been implicated in the disruption of neural connections, brain growth, and synaptic/dendritic morphology [27,28,29]. Metabolic errors including phenylketonuria, creatine deficiency syndromes, adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency, and metabolic purine disorders are also account for less than 5% of individuals with ASD [30]. Recently, the correlation between cerebellar developmental patterning gene ENGRAILED 2 and autism was reported [31]. It is the first genetic allele that contributes to ASD susceptibility in as many as 40% of ASD cases. Other genes such as UBE3A locus, GABA system genes, and serotonin transporter genes have also been considered as the genetic factors for ASD [18].

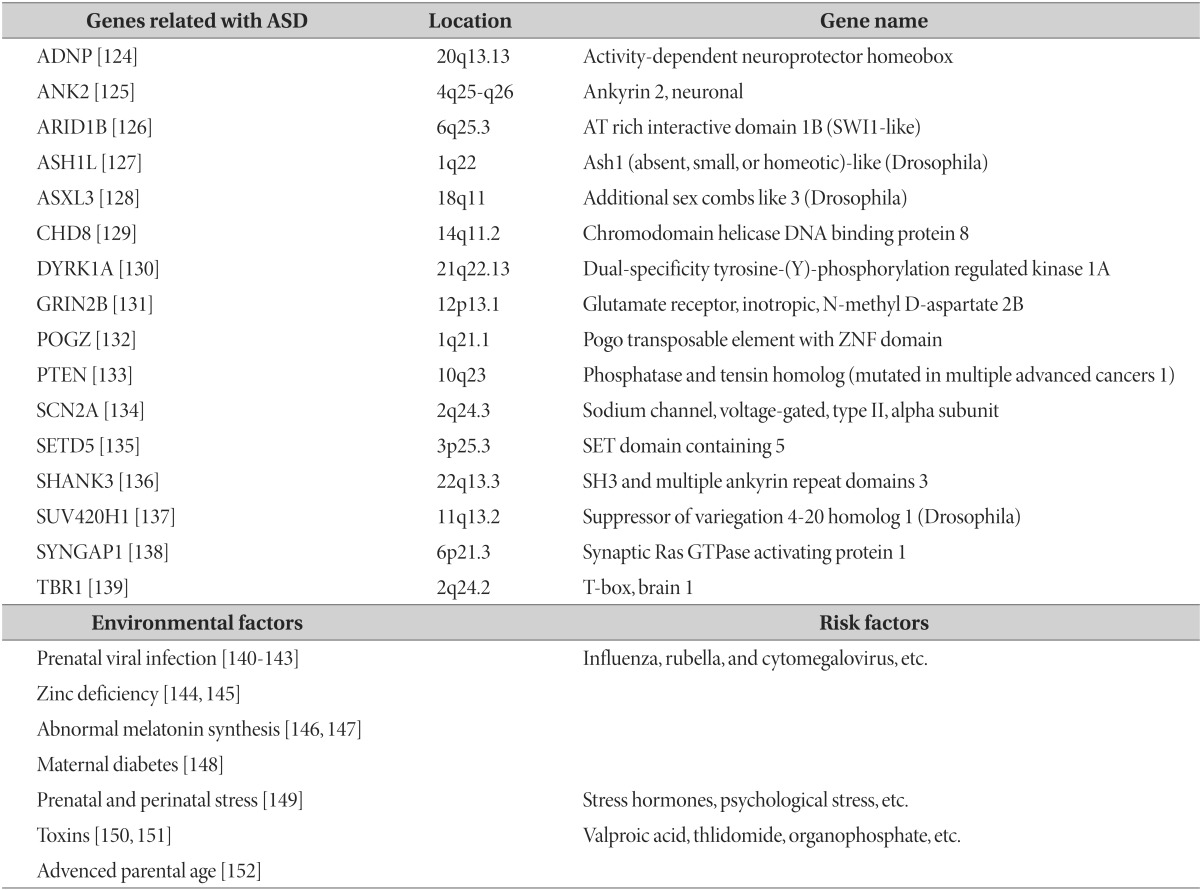

Diverse environmental causative elements including pre-natal, peri-natal, and post-natal factors also contribute to ASD [32]. Prenatal factors related with ASD include exposure to teratogens such as thalidomide, certain viral infections (congenital rubella syndrome), and maternal anticonvulsants such as valproic acid [33,34]. Low birth weight, abnormally short gestation length, and birth asphyxia are the peri-natal factors [34]. Reported post-natal factors associated with ASD include autoimmune disease, viral infection, hypoxia, mercury toxicity, and others [33,35,36]. Table 1 summarizes the known and putative ASD-related genes and environmental factors contributing to the ASD.

Table 1. The known and putative ASD-related genes and environmental factors contributing to the ASD.

In recent years, some researchers suggest that ASD is the result of complex interactions between genetic and environmental risk factors [37]. Understanding the interaction between genetic and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of ASD will lead to optimal treatment strategy.

Clinical features and Diagnosis

ASD is typically noticed in the first 3 years of life, with deficits in social behaviors and nonverbal interactions such as reduced eye contact, facial expression, and body gestures [1]. Children also manifest with non-specific symptoms such as unusual sensory perception skills and experiences, motor clumsiness, and insomnia. Associated phenomena include mental retardation, emotional indifference, hyperactivity, aggression, self-injury, and repetitive behaviors such as body rocking or hand flapping. Repetitive, stereotyped behaviors are often accompanied by cognitive impairment, seizures or epilepsy, gastrointestinal complaints, disturbedd sleep, and other problems. Differential diagnosis includes childhood schizophrenia, learning disability, and deafness [38,39].

ASD is diagnosed clinically based on the presence of core symptoms. However, caution is required when diagnosing ASD because of non-specific manifestations in different age groups and individual abilities in intelligence and verbal domains. The earliest nonspecific signs recognized in infancy or toddlers include irritability, passivity, and difficulties with sleeping and eating, followed by delays in language and social engagement. In the first year of age, infants later diagnosed with ASD cannot be easily distinguished from control infants. However, some authors report that about 50% of infants show behavioral abnormalities including extremes of temperament, poor eye contact, and lack of response to parental voices or interaction. At 12 months of age, individuals with ASD show atypical behaviors, across the domains of visual attention, imitation, social responses, motor control, and reactivity [40]. There is also report about atypical language trajectories, with mild delays at 12 months progressing to more severe delays by 24 months [40]. By 3 years of age, the typical core symptoms such as lack of social communication and restricted/repetitive behaviors and interests are manifested. ASD can be easily differentiated from other psychosocial disorders in late preschool and early school years.

Amygdala and ASD

The frontal and temporal lobes are the markedly affected brain areas in the individuals with ASD. In particular, the role of amygdala in cognition and ASD has been proved in numerous neuropathological and neuroimaging studies. The amygdala located the medial temporal lobe anterior to the hippocampal formation has been thought to have a strong association with social and aggressive behaviors in patients with ASD [41,42]. The amygdala is a major component of the limbic system and affective loop of the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuit [43].

The amygdala has 2 specific functions including eye gaze and face processing [44]. The lesion of the amygdala results in fear-processing, modulation of memory with emotional content, and eye gaze when looking at human face [45,46,47]. The findings in individuals with amygdala lesion are similar to the phenomena in ASD. The amygdala receives highly processed somatosensory, visual, auditory, and all types of visceral inputs. It sends efferents through two major pathways, the stria terminalis and the ventral amygdalofugal pathway.

The amygdala comprises a collection of 13 nuclei. Based on histochemical analyses, these 13 nuclei are divided into three primary subgroups: the basolateral (BL), centromedial (CM), and superficial groups [42]. The BL group attributes amygdala to have a role as a node connecting sensory stimuli to higher social cognition level. It links the CM and superficial groups, and it has reciprocal connection with the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) [48]. The BL group contains neurons responsive to faces and actions of others, which is not found in the other two groups of amygdala [49,50]. The CM group consists of the central, medial, cortical nuclei, and the periamygdaloid complex. It innervates many of the visceral and autonomic effector regions of the brain stem, and provides a major output to the hypothalamus, thalamus, ventral tegmental area, and reticular formation [51]. The superficial group includes the nucleus of the lateral olfactory tract [42].

Neurochemistrial studies revealed high density of benzodiazepine/GABAa receptors and a substantial set of opiate receptors in the amygdala. It also includes serotonergic, dopaminergic, cholinergic, and noradrenergic cell bodies and pathways [52]. Since some patients with temporal epilepsy and aggressive behavior experienced improvement in aggressiveness after bilateral stereotactic ablation of basal and corticomedial amygdaloid nuclei, the role of amygdala in emotional processing, especially rage processing has been investigated [53,54,55,56]. Some evidences for the amygdala deficit in patients with ASD have been suggested. Post-mortem studies found the pathology in the amygdala of individuals with ASD compared to age- and sex-matched controls [57,58,59]. Small neuronal size and increased cell density in the cortical, medial, and central nuclei of the amygdala were detected in ASD patients.

Several studies proposed the use of an animal model to confirm the evidence for the association between amygdala and ASD [60,61]. Despite the limitation which stems from the need to prove higher order cognitive disorder, the studies suggested that disease-associated alterations in the temporal lobes during experimental manipulations of the amygdala in animals have produced some symptoms of ASD [62]. Especially, the Kluver-Bucy syndrome, which is caused by bilateral damage to the anterior temporal lobes in monkeys, has characteristic manifestations similar to ASD [63,64]. Monkeys with the Kluver-Bucy syndrome shows absence of social chattering, lack of facial expression, absence of emotional reactions, repetitive abnormal movement patterns, and increased aggression. Sajdyk et al. performed experiments on rats and discovered that physiological activation of the BL nucleus of the amygdala by blocking tonic GABAergic inhibition or enhancing glutamate or the stress-associated peptide corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-mediated excitation caused reduction in social behaviors [65]. On the contrary, lesioning of the amygdala or blocking amygdala excitability with glutamate antagonist increased dyadic social interactions [60]. Besides animals, humans who underwent lesioning of the amygdala showed impairments in social judgment. This phenomenon is called acquired ASD [66,67,68]. The pattern of social deficits was similar in idiopathic and acquired ASD [69]. Felix-Ortiz and Tye sought to understand the role of projections from the BL amygdala to the ventral hippocampus in relation to behavior. Their study using mice showed that the BLS-ventral hippocampus pathway involved in anxiety plays a role in the mediation of social behavior as well [70].

The individuals with temporal lobe tumors involving the amygdala and hippocampus provide another evidence of the correlation between the amygdala and ASD. Some authors reported that patients experienced autistic symptoms after temporal lobe was damaged by a tumor [71,72]. Also, individuals with tuberous sclerosis experienced similar symptoms including facial expression due to a temporal lobe hamartoma [73].

Although other researchers failed to find structural abnormalities in the mesial temporal lobe of autistic subjects by performing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies [74,75,76], recent development in neuroimaging has facilitated the investigation of amygdala pathology in ASD. Studies using structural MRI estimated volumes of the amygdala and related structures in individuals with ASD and age-, gender, and verbal IQ-matched healthy controls [77]. Increase in bilateral amygdala volume and reduction in hippocampal and parahippocampal gyrus volumes were noted in individuals with ASD. Also, the lateral ventricles and intracranial volumes were significantly increased in the autistic subjects; however, overall temporal lobe volumes were similar between the ASD and control groups.

There was a significant difference in the whole brain voxel-based scans of individuals with ASD and control groups [78]. Individuals with ASD showed decreased gray matter volume in the right paracingulate sulcus, the left occipito-temporal cortex, and the left inferior frontal sulcus. On the contrary, the gray matter volume in the bilateral cerebellum was increased. Otherwise, they showed increased volume in the left amygdala/periamygdaloid cortex, the right inferior temporal gyrus, and the middle temporal gyrus.

Recently, the development of functional neuroimaging also provided some evidence for the correlation between amygdala deficit and ASD. A study using Technetium-99m (Tc-99m) single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) found that regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) was decreased in the bilateral insula, superior temporal gyri, and left prefrontal cortices in individuals with ASD compared to age- and gender-matched controls with mental retardation [79]. Also, the authors found that rCBF in both the right hippocampus and amygdala was correlated with a behavioral rating subscale.

On proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) in the right hippocampal-amygdala region and the left cerebellar hemisphere, autistic subjects showed decreased level of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) in both areas [80]. There was no difference in the level of the other metabolites, such as creatine and choline. This study implies that a decreased level of NAA might be associated with neuronal hypofunction or immature neurons.

These findings support the claim that amygdala might be a key structure in the development of ASD and a target for the management of the disease.

Prefrontal cortex and ASD

Frontal lobe has been considered as playing an important role in higher-level control and a key structure associated with autism. Individuals with frontal lobe deficit demonstrate higher-order cognitive, language, social, and emotion dysfunction, which is deficient in autism [81]. Recently, neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies have attempted to delineate distinct regions of prefrontal cortex supporting different aspects of executive function. Some authors have reported that the excessive rates of brain growth in infants with ASD, which is mainly contributed by the increase of frontal cortex volume [82,83]. Especially, the PFC including Brodmann areas 8, 9, 10, 11, 44, 45, 46, and 47 has been noted for the structure related with ASD [84]. The PFC is cytoarchitectonically defined as the presence of a cortical granular layer IV [85], and anatomically refers to the regions of the cerebral cortex that are anterior to premotor cortex and the supplementary motor area [86]. The PFC has extensive connections with other cortical, subcortical and brain stem sites [87]. It receives inputs from the brainstem arousal systems, and its function is particularly dependent on its neurochemical environment [88].

The PFC is broadly divided into the medial PFC (mPFC) and the lateral PFC (lPFC). The mPFC is further divided into four distinct regions: medial precentral cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, prelimbic and infralimbic prefrontal cortex [89]. While the lPFC is thought to support cognitive control process [90], the mPFC has reciprocal connections with brain regions involved in emotional processing (amygdala), memory (hippocampus) and higher-order sensory regions (within temporal cortex) [91]. This involvement of mPFC in social cognition and interaction implies that mPFC might be a key region in understanding self and others [92].

The mPFC involves in fear learning and extinction by reciprocal synaptic connections with the basolateral amygdala [93,94]. It is believed that the mPFC regulates and controls amygdala output and the accompanying behavioral phenomena [95,96]. Previous authors investigated how memory processing is regulated by interactions between BLA and mPFC by means of functional disconnection [97,98]. Disturbed communication within amygdala-mPFC circuitry caused deficits in memory processing. These informations provide support for a role of the mPFC in the development of ASD.

Nucleus Accumbens and ASD

Besides amygdala, nucleus accumbens (NAc) is also considered as the key structure which is related with the social reward response in ASD. NAc borders ventrally on the anterior limb of the internal capsule, and the lateral subventricular fundus of the NAc is permeated in rostral sections by internal capsule fiber bundles. The rationale for NAc to be considered as the potential target of DBS for ASD is its predominant role in modulating the processing of reward and pleasure [99]. Anticipation of rewarding stimuli recruits the NAc as well as other limbic structures, and the experience of pleasure activates the NAc as well as the caudate, putamen, amygdala, and VMPFC [100,101,102]. It is well known that dysfunction of NAc regarding rewarding stimuli in subjects with depression. Bewernick et al. demonstrated antidepressant effects of NAc-DBS in 5 of the 10 patients suffering from severe treatment-resistant depression [103].

Two groups reported about the neural basis of social reward processing in ASD. Schmitz et al. examined responses to a task that involved monetary reward. They investigated the neural substrates of reward feedback in the context of a sustained attention task, and found increased activation in the left anterior cingulate gyrus and left mid-frontal gyrus on rewarded trials in ASD [104]. Scott-Van Zeeland et al. investigated the neural correlates of rewarded implicit learning in children with ASD using both social and monetary rewards. They found diminished ventral striatal response during social, but not monetary, rewarded learning [105]. According to them, activity within the ventral striatum predicted social reciprocity within the control group, but not within the ASD group.

Anticipation of pleasurable stimuli recruits the NAc, whereas the experience of pleasure activates VMPFC [106]. NAc is activated by incentive motivation to reach salient goals [106]. Increased activation in the left anterior cingulate gyrus and left mid-frontal gyrus was noted during both the anticipatory and consummatory phase of the reward response [104,107,108]. However, the activity within the ventral striatum was decreased in autistic subjects, which caused impairment in social reciprocity [105].

These findings indicate that reward network function in ASD is contingent on both the temporal phase of the response and the type of reward processed, suggesting that it is critical to assess the temporal chronometry of responses in a study of reward processing in ASD. NAc might be one of the candidates as a target of DBS which is introduced as below.

Treatment

Various educational and behavioral treatments have been the mainstay of the management of ASD. Most experts agree that the treatment for ASD should be individualized. Treatment of disabling symptoms such as aggression, agitation, hyperactivity, inattention, irritability, repetitive and self-injurious behavior may allow educational and behavioral interventions to proceed more effectively [109].

Increasing interest is being shown in the role of various pharmacological treatments. Medical management includes typical antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics, antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, α2-adrenergic agonists, β-adrenergic antagonist, mood stabilizers, and anticonvulsants [110,111]. So far, there has been no agent which has been proved effective in social communication [112]. A major factor in the choice of pharmacologic treatment is awareness of specific individual physical, behavioral or psychiatric conditions comorbid with ASD, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, mood disorder, and intellectual disability [113]. Antidepressants were the most commonly used agents followed by stimulants and antipsychotics. The high prevalence of comorbidities is reflected in the rates of psychotropic medication use in people with ASD. Antipsychotics were effective in treating the repetitive behaviors in children with ASD; however, there was not sufficient evidence on the efficacy and safety in adolescents and adults [114]. There are also alternative options including opiate antagonist, immunotherapy, hormonal agents, megavitamins and other dietary supplements [109,113].

However, the autistic symptoms remain refractory to medication therapy in some patients [115]. These individuals have severely progressed disease and multiple comorbidities causing decreased quality of life [44,110]. Interventional therapy such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) may be an alternative therapeutic option for these patients.

Two kinds of interventions have been used for treating ASD; focused intervention practices and comprehensive treatments [116]. The focused intervention practices include prompting, reinforcement, discrete trial teaching, social stories, or peer-mediated interventions. These are designed to produce specific behavioral or developmental outcomes for individual children with ASD, and used for a limited time period with the intent of demonstrating a change in the targeted behaviors. The comprehensive treatment models are a set of practices performed over an extended period of time and are intense in their application, and usually have multiple components [116].

Since it was approved by the FDA in 1997, DBS has been used to send electrical impulses to specific parts of the brain [117,118]. In recent years, the spectrum for which therapeutic benefit is provided by DBS has widely been expanded from movement disorders such as Parkinson's disease, essential tremor, and dystonia to psychiatric disorders. Some authors have demonstrated the efficacy of DBS for psychiatric disorders including refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, Tourette syndrome, and others for the past few years [119,120,121].

To the best of our knowledge, there have been 2 published articles of 3 patients who underwent DBS for ASD accompanied by life-threatening self-injurious behaviors not alleviated by antipsychotic medication [122,123]. The targets were anterior limb of the internal capsule and globus pallidus internus, only globus pallidus, and BL nucleus of the amygdala, respectively. All patients obtained some benefit from DBS. Although the first patient showed gradual re-deterioration after temporary improvement, the patient who underwent DBS of the BL nucleus experienced substantial improvement in self-injurious behavior and social communication. These experiences suggested the possibility of DBS for the treatment of ASD. For patients who did not obtain benefit from other treatments, DBS may be a viable therapeutic option. Understanding the structures which contribute to the occurrence of ASD might open a new horizon for management of ASD, particularly DBS. Accompanying development of neuroimaging technique enables more accurate targeting and heightens the efficacy of DBS. However, the optimal DBS target and stimulation parameters are still unknown, and prospective controlled trials of DBS for various possible targets are required to determine optimal target and stimulation parameters for the safety and efficacy of DBS.

Conclusion

ASD should be considered as a complex disorder. It has many etiologies involving genetic and environmental factors, and further evidence for the role of amygdala and NA in the pathophysiology of ASD has been obtained from numerous studies. However, the key architecture of ASD development which could be a target for treatment is still an uncharted territory. Further work is needed to broaden the horizons on the understanding of ASD.

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by the Korea Institute of Planning & Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Republic of Korea (311011-05-3-SB020), by the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project (HI11C21100200) funded by Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea, by the Technology Innovation Program (10050154, Business Model Development for Personalized Medicine Based on Integrated Genome and Clinical Information) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MI, Korea), and by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Korean government, MSIP (2015M3C7A1028926).

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattila ML, Kielinen M, Linna SL, Jussila K, Ebeling H, Bloigu R, Joseph RM, Moilanen I. Autism spectrum disorders according to DSM-IV-TR and comparison with DSM-5 draft criteria: an epidemiological study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:583–592.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YS, Leventhal BL, Koh YJ, Fombonne E, Laska E, Lim EC, Cheon KA, Kim SJ, Kim YK, Lee H, Song DH, Grinker RR. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in a total population sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:904–912. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisch GS. Nosology and epidemiology in autism: classification counts. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160C:91–103. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elsabbagh M, Divan G, Koh YJ, Kim YS, Kauchali S, Marcín C, Montiel-Nava C, Patel V, Paula CS, Wang C, Yasamy MT, Fombonne E. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. 2012;5:160–179. doi: 10.1002/aur.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fombonne E. Incidence and prevalence of pervasive developmental disorders. In: Hollander E, Kolevzon A, Coyle JT, editors. Textbook of autism spectrum disorders. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2011. pp. 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saemundsen E, Ludvigsson P, Rafnsson V. Autism spectrum disorders in children with a history of infantile spasms: a population-based study. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:1102–1107. doi: 10.1177/0883073807306251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baron-Cohen S, Lombardo MV, Auyeung B, Ashwin E, Chakrabarti B, Knickmeyer R. Why are autism spectrum conditions more prevalent in males? PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson EB, Lichtenstein P, Anckarsäter H, Happé F, Ronald A. Examining and interpreting the female protective effect against autistic behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5258–5262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bleuler E. The theory of schizophrenic negativism. New York, NY: The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company; 1912. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asperger H. Die "Autistischen Psychopathen" im Kindesalter. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1944;117:76–136. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child. 1943;2:217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Publishing. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinha S, McGovern RA, Sheth SA. Deep brain stimulation for severe autism: from pathophysiology to procedure. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;38:E3. doi: 10.3171/2015.3.FOCUS1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banerjee S, Riordan M, Bhat MA. Genetic aspects of autism spectrum disorders: insights from animal models. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:58. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ecker C, Bookheimer SY, Murphy DG. Neuroimaging in autism spectrum disorder: brain structure and function across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1121–1134. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman GE, Henninger N, Ratliff-Schaub K, Pastore M, Fitzgerald S, McBride KL. Genetic testing in autism: how much is enough? Genet Med. 2007;9:268–274. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31804d683b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miles JH. Autism spectrum disorders--a genetics review. Genet Med. 2011;13:278–294. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ff67ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szatmari P, Jones MB, Zwaigenbaum L, MacLean JE. Genetics of autism: overview and new directions. J Autism Dev Disord. 1998;28:351–368. doi: 10.1023/a:1026096203946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang J, Gilman SR, Chiang AH, Sanders SJ, Vitkup D. Genotype to phenotype relationships in autism spectrum disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:191–198. doi: 10.1038/nn.3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geschwind DH. Genetics of autism spectrum disorders. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voineagu I, Wang X, Johnston P, Lowe JK, Tian Y, Horvath S, Mill J, Cantor RM, Blencowe BJ, Geschwind DH. Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature. 2011;474:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clifford S, Dissanayake C, Bui QM, Huggins R, Taylor AK, Loesch DZ. Autism spectrum phenotype in males and females with fragile X full mutation and premutation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:738–747. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0205-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curatolo P, Bombardieri R. Tuberous sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2008;87:129–151. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)87009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wassink TH, Brzustowicz LM, Bartlett CW, Szatmari P. The search for autism disease genes. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:272–283. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Zwaigenbaum L, Szatmari P, Scherer SW. Molecular cytogenetics of autism. Curr Genomics. 2004;5:347–364. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dykens EM, Sutcliffe JS, Levitt P. Autism and 15q11-q13 disorders: behavioral, genetic, and pathophysiological issues. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:284–291. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss LA, Shen Y, Korn JM, Arking DE, Miller DT, Fossdal R, Saemundsen E, Stefansson H, Ferreira MA, Green T, Platt OS, Ruderfer DM, Walsh CA, Altshuler D, Chakravarti A, Tanzi RE, Stefansson K, Santangelo SL, Gusella JF, Sklar P, Wu BL, Daly MJ Autism Consortium. Association between microdeletion and microduplication at 16p11.2 and autism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:667–675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casas KA, Mononen TK, Mikail CN, Hassed SJ, Li S, Mulvihill JJ, Lin HJ, Falk RE. Chromosome 2q terminal deletion: report of 6 new patients and review of phenotype-breakpoint correlations in 66 individuals. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130A:331–339. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manzi B, Loizzo AL, Giana G, Curatolo P. Autism and metabolic diseases. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:307–314. doi: 10.1177/0883073807308698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gharani N, Benayed R, Mancuso V, Brzustowicz LM, Millonig JH. Association of the homeobox transcription factor, ENGRAILED 2, 3, with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:474–484. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.London EA, Etzel RA. The environment as an etiologic factor in autism: a new direction for research. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):401–404. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kern JK, Jones AM. Evidence of toxicity, oxidative stress, and neuronal insult in autism. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2006;9:485–499. doi: 10.1080/10937400600882079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolevzon A, Gross R, Reichenberg A. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism: a review and integration of findings. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:326–333. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashwood P, Van de Water J. Is autism an autoimmune disease? Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davidson PW, Myers GJ, Weiss B. Mercury exposure and child development outcomes. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1023–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim YS, Leventhal BL. Genetic epidemiology and insights into interactive genetic and environmental effects in autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fombonne E. The epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. In: Casanova MF, editor. Recent developments in autism research. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers Inc.; 2005. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zwaigenbaum L, Bryson S, Rogers T, Roberts W, Brian J, Szatmari P. Behavioral manifestations of autism in the first year of life. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aggleton JP. The functional effects of amygdala lesions in humans: a comparison with findings from monkeys. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The amygdala: neurobiological aspects of emotion, memory, and mental dysfunction. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss; 1992. pp. 485–503. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sah P, Faber ES, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J. The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:803–834. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Baron-Cohen S. Autism. Lancet. 2014;383:896–910. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adolphs R, Gosselin F, Buchanan TW, Tranel D, Schyns P, Damasio AR. A mechanism for impaired fear recognition after amygdala damage. Nature. 2005;433:68–72. doi: 10.1038/nature03086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adolphs R, Tranel D, Buchanan TW. Amygdala damage impairs emotional memory for gist but not details of complex stimuli. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:512–518. doi: 10.1038/nn1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spezio ML, Huang PY, Castelli F, Adolphs R. Amygdala damage impairs eye contact during conversations with real people. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3994–3997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3789-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adolphs R. What does the amygdala contribute to social cognition? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1191:42–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rolls ET. Neurophysiology and functions of the primate amygdala. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The amygdala. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss; 1992. pp. 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brothers L, Ring B, Kling A. Response of neurons in the macaque amygdala to complex social stimuli. Behav Brain Res. 1990;41:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(90)90108-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Veinante P, Yalcin I, Barrot M. The amygdala between sensation and affect: a role in pain. J Mol Psychiatry. 2013;1:9. doi: 10.1186/2049-9256-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nolte J. The human brain: an introduction to its functional anatomy. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luczywek E, Mempel E. Stereotactic amygdalotomy in the light of neuropsychological investigations. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1976;23:221–223. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-8444-8_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mempel E, Witkiewicz B, Stadnicki R, Łuczywek E, Kuciński L, Pawłowski G, Nowak J. The effect of medial amygdalotomy and anterior hippocampotomy on behavior and seizures in epileptic patients. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1980;30:161–167. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-8592-6_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Narabayashi H, Nagao T, Saito Y, Yoshida M, Nagahata M. Stereotaxic amygdalotomy for behavior disorders. Arch Neurol. 1963;9:1–16. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1963.00460070011001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Narabayashi H, Uno M. Long range results of stereotaxic amygdalotomy for behavior disorders. Confin Neurol. 1966;27:168–171. doi: 10.1159/000103950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bauman ML, Kemper TL. The neurobiology of autism. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rapin I, Katzman R. Neurobiology of autism. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:7–14. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kemper TL, Bauman M. Neuropathology of infantile autism. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:645–652. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sajdyk TJ, Shekhar A. Excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists block the cardiovascular and anxiety responses elicited by γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor blockade in the basolateral amygdala of rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:969–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Emery NJ, Clayton NS. Effects of experience and social context on prospective caching strategies by scrub jays. Nature. 2001;414:443–446. doi: 10.1038/35106560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sweeten TL, Posey DJ, Shekhar A, McDougle CJ. The amygdala and related structures in the pathophysiology of autism. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:449–455. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klüver H, Bucy PC. Preliminary analysis of functions of the temporal lobes in monkeys. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1939;42:979–1000. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hetzler BE, Griffin JL. Infantile autism and the temporal lobe of the brain. J Autism Dev Disord. 1981;11:317–330. doi: 10.1007/BF01531514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sajdyk TJ, Shekhar A. Sodium lactate elicits anxiety in rats after repeated GABA receptor blockade in the basolateral amygdala. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;394:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio A. Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature. 1994;372:669–672. doi: 10.1038/372669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Young AW, Hellawell DJ, Van De Wal C, Johnson M. Facial expression processing after amygdalotomy. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34:31–39. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stone V. The role of the frontal lobes and the amygdala in theory of mind. In: Baron-Cohen S, Tager-Flusberg H, Cohen DJ, editors. Understanding other minds: perspectives from autism. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 253–273. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adolphs R, Sears L, Piven J. Abnormal processing of social information from faces in autism. J Cogn Neurosci. 2001;13:232–240. doi: 10.1162/089892901564289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Felix-Ortiz AC, Tye KM. Amygdala inputs to the ventral hippocampus bidirectionally modulate social behavior. J Neurosci. 2014;34:586–595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4257-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Taylor DC, Neville BG, Cross JH. Autistic spectrum disorders in childhood epilepsy surgery candidates. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;8:189–192. doi: 10.1007/s007870050128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoon AH, Jr, Reiss AL., Jr The mesial-temporal lobe and autism: case report and review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34:252–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb14999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bolton PF, Griffiths PD. Association of tuberous sclerosis of temporal lobes with autism and atypical autism. Lancet. 1997;349:392–395. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)80012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haznedar MM, Buchsbaum MS, Wei TC, Hof PR, Cartwright C, Bienstock CA, Hollander E. Limbic circuitry in patients with autism spectrum disorders studied with positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1994–2001. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Courchesne E, Press GA, Yeung-Courchesne R. Parietal lobe abnormalities detected with MR in patients with infantile autism. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:387–393. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.2.8424359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nowell MA, Hackney DB, Muraki AS, Coleman M. Varied MR appearance of autism: fifty-three pediatric patients having the full autistic syndrome. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:811–816. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90018-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Howard MA, Cowell PE, Boucher J, Broks P, Mayes A, Farrant A, Roberts N. Convergent neuroanatomical and behavioural evidence of an amygdala hypothesis of autism. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2931–2935. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009110-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abell F, Krams M, Ashburner J, Passingham R, Friston K, Frackowiak R, Happé F, Frith C, Frith U. The neuroanatomy of autism: a voxel-based whole brain analysis of structural scans. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1647–1651. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199906030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ohnishi T, Matsuda H, Hashimoto T, Kunihiro T, Nishikawa M, Uema T, Sasaki M. Abnormal regional cerebral blood flow in childhood autism. Brain. 2000;123:1838–1844. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.9.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Otsuka H, Harada M, Mori K, Hisaoka S, Nishitani H. Brain metabolites in the hippocampus-amygdala region and cerebellum in autism: an 1H-MR spectroscopy study. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:517–519. doi: 10.1007/s002340050795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stuss DT, Knight RT. Principles of frontal lobe function. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herbert MR, Ziegler DA, Makris N, Filipek PA, Kemper TL, Normandin JJ, Sanders HA, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS., Jr Localization of white matter volume increase in autism and developmental language disorder. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:530–540. doi: 10.1002/ana.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Courchesne E, Mouton PR, Calhoun ME, Semendeferi K, Ahrens-Barbeau C, Hallet MJ, Barnes CC, Pierce K. Neuron number and size in prefrontal cortex of children with autism. JAMA. 2011;306:2001–2010. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Preuss TM. Do rats have prefrontal cortex? The Rose-Woolsey-Akert program reconsidered. J Cogn Neurosci. 1995;7:1–24. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1995.7.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Finger S. Origins of neuroscience: a history of explorations into brain function. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zelazo PD, Müller U. Chapter 20. Executive function in typical and atypical development. In: Goswami U, editor. Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.; 2002. pp. 445–469. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alvarez JA, Emory E. Executive function and the frontal lobes: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2006;16:17–42. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Robbins TW, Arnsten AF. The neuropsychopharmacology of fronto-executive function: monoaminergic modulation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:267–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Heidbreder CA, Groenewegen HJ. The medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: evidence for a dorso-ventral distinction based upon functional and anatomical characteristics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:555–579. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim MJ, Whalen PJ. The structural integrity of an amygdala-prefrontal pathway predicts trait anxiety. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11614–11618. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2335-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wood JN, Grafman J. Human prefrontal cortex: processing and representational perspectives. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:139–147. doi: 10.1038/nrn1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Frith CD, Frith U. The neural basis of mentalizing. Neuron. 2006;50:531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Quirk GJ, Mueller D. Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:56–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sotres-Bayon F, Quirk GJ. Prefrontal control of fear: more than just extinction. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bishop SJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms of anxiety: an integrative account. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Quirk GJ, Beer JS. Prefrontal involvement in the regulation of emotion: convergence of rat and human studies. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fuchs RA, Eaddy JL, Su ZI, Bell GH. Interactions of the basolateral amygdala with the dorsal hippocampus and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex regulate drug context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:487–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mashhoon Y, Wells AM, Kantak KM. Interaction of the rostral basolateral amygdala and prelimbic prefrontal cortex in regulating reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;96:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cohen MX, Axmacher N, Lenartz D, Elger CE, Sturm V, Schlaepfer TE. Neuroelectric signatures of reward learning and decision-making in the human nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1649–1658. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Knutson B, Adams CM, Fong GW, Hommer D. Anticipation of increasing monetary reward selectively recruits nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ernst M, Nelson EE, McClure EB, Monk CS, Munson S, Eshel N, Zarahn E, Leibenluft E, Zametkin A, Towbin K, Blair J, Charney D, Pine DS. Choice selection and reward anticipation: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:1585–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wacker J, Dillon DG, Pizzagalli DA. The role of the nucleus accumbens and rostral anterior cingulate cortex in anhedonia: integration of resting EEG, fMRI, and volumetric techniques. Neuroimage. 2009;46:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schlaepfer TE, Cohen MX, Frick C, Kosel M, Brodesser D, Axmacher N, Joe AY, Kreft M, Lenartz D, Sturm V. Deep brain stimulation to reward circuitry alleviates anhedonia in refractory major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:368–377. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schmitz N, Rubia K, van Amelsvoort T, Daly E, Smith A, Murphy DG. Neural correlates of reward in autism. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:19–24. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Scott-Van Zeeland AA, Dapretto M, Ghahremani DG, Poldrack RA, Bookheimer SY. Reward processing in autism. Autism Res. 2010;3:53–67. doi: 10.1002/aur.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Knutson B, Cooper JC. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of reward prediction. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000173463.24758.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kim H, Shimojo S, O'Doherty JP. Is avoiding an aversive outcome rewarding? Neural substrates of avoidance learning in the human brain. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Forbes EE, Hariri AR, Martin SL, Silk JS, Moyles DL, Fisher PM, Brown SM, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Dahl RE. Altered striatal activation predicting real-world positive affect in adolescent major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:64–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Posey DJ, McDougle CJ. Pharmacotherapeutic management of autism. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:587–600. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Adler BA, Wink LK, Early M, Shaffer R, Minshawi N, McDougle CJ, Erickson CA. Drug-refractory aggression, self-injurious behavior, and severe tantrums in autism spectrum disorders: a chart review study. Autism. 2015;19:102–106. doi: 10.1177/1362361314524641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stigler KA, McDonald BC, Anand A, Saykin AJ, McDougle CJ. Structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging of autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. 2011;1380:146–161. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Farmer C, Thurm A, Grant P. Pharmacotherapy for the core symptoms in autistic disorder: current status of the research. Drugs. 2013;73:303–314. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kerbeshian J, Burd L, Avery K. Pharmacotherapy of autism: A review and clinical approach. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2001;13:199–228. [Google Scholar]

- 114.McPheeters ML, Warren Z, Sathe N, Bruzek JL, Krishnaswami S, Jerome RN, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. A systematic review of medical treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1312–e1321. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Richards C, Oliver C, Nelson L, Moss J. Self-injurious behaviour in individuals with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2012;56:476–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Odom SL, Boyd BA, Hall LJ, Hume K. Evaluation of comprehensive treatment models for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:425–436. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0825-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Benabid AL. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:696–706. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lozano AM, Dostrovsky J, Chen R, Ashby P. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: disrupting the disruption. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hamani C, Pilitsis J, Rughani AI, Rosenow JM, Patil PG, Slavin KS, Abosch A, Eskandar E, Mitchell LS, Kalkanis S American Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery; Congress of Neurological Surgeons; CNS and American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: systematic review and evidence-based guideline sponsored by the American Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) and endorsed by the CNS and American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Neurosurgery. 2014;75:327–333. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Taghva AS, Malone DA, Rezai AR. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. World Neurosurg. 2013;80:S27.e17–S27.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Schrock LE, Mink JW, Woods DW, Porta M, Servello D, Visser-Vandewalle V, Silburn PA, Foltynie T, Walker HC, Shahed-Jimenez J, Savica R, Klassen BT, Machado AG, Foote KD, Zhang JG, Hu W, Ackermans L, Temel Y, Mari Z, Changizi BK, Lozano A, Auyeung M, Kaido T, Agid Y, Welter ML, Khandhar SM, Mogilner AY, Pourfar MH, Walter BL, Juncos JL, Gross RE, Kuhn J, Leckman JF, Neimat JA, Okun MS Tourette Syndrome Association International Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) Database and Registry Study Group. Tourette syndrome deep brain stimulation: a review and updated recommendations. Mov Disord. 2015;30:448–471. doi: 10.1002/mds.26094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sturm V, Fricke O, Bührle CP, Lenartz D, Maarouf M, Treuer H, Mai JK, Lehmkuhl G. DBS in the basolateral amygdala improves symptoms of autism and related self-injurious behavior: a case report and hypothesis on the pathogenesis of the disorder. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:341. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Stocco A, Baizabal-Carvallo JF. Deep brain stimulation for severe secondary stereotypies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:1035–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Helsmoortel C, Vulto-van Silfhout AT, Coe BP, Vandeweyer G, Rooms L, van den Ende J, Schuurs-Hoeijmakers JH, Marcelis CL, Willemsen MH, Vissers LE, Yntema HG, Bakshi M, Wilson M, Witherspoon KT, Malmgren H, Nordgren A, Annerén G, Fichera M, Bosco P, Romano C, de Vries BB, Kleefstra T, Kooy RF, Eichler EE, Van der Aa N. A SWI/SNF-related autism syndrome caused by de novo mutations in ADNP. Nat Genet. 2014;46:380–384. doi: 10.1038/ng.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Willsey AJ, Sanders SJ, Li M, Dong S, Tebbenkamp AT, Muhle RA, Reilly SK, Lin L, Fertuzinhos S, Miller JA, Murtha MT, Bichsel C, Niu W, Cotney J, Ercan-Sencicek AG, Gockley J, Gupta AR, Han W, He X, Hoffman EJ, Klei L, Lei J, Liu W, Liu L, Lu C, Xu X, Zhu Y, Mane SM, Lein ES, Wei L, Noonan JP, Roeder K, Devlin B, Sestan N, State MW. Coexpression networks implicate human midfetal deep cortical projection neurons in the pathogenesis of autism. Cell. 2013;155:997–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Halgren C, Kjaergaard S, Bak M, Hansen C, El-Schich Z, Anderson CM, Henriksen KF, Hjalgrim H, Kirchhoff M, Bijlsma EK, Nielsen M, den Hollander NS, Ruivenkamp CA, Isidor B, Le Caignec C, Zannolli R, Mucciolo M, Renieri A, Mari F, Anderlid BM, Andrieux J, Dieux A, Tommerup N, Bache I. Corpus callosum abnormalities, intellectual disability, speech impairment, and autism in patients with haploinsufficiency of ARID1B. Clin Genet. 2012;82:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cotney J, Muhle RA, Sanders SJ, Liu L, Willsey AJ, Niu W, Liu W, Klei L, Lei J, Yin J, Reilly SK, Tebbenkamp AT, Bichsel C, Pletikos M, Sestan N, Roeder K, State MW, Devlin B, Noonan JP. The autism-associated chromatin modifier CHD8 regulates other autism risk genes during human neurodevelopment. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6404. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.De Rubeis S, He X, Goldberg AP, Poultney CS, Samocha K, Cicek AE, Kou Y, Liu L, Fromer M, Walker S, Singh T, Klei L, Kosmicki J, Shih-Chen F, Aleksic B, Biscaldi M, Bolton PF, Brownfeld JM, Cai J, Campbell NG, Carracedo A, Chahrour MH, Chiocchetti AG, Coon H, Crawford EL, Curran SR, Dawson G, Duketis E, Fernandez BA, Gallagher L, Geller E, Guter SJ, Hill RS, Ionita-Laza J, Jimenz Gonzalez P, Kilpinen H, Klauck SM, Kolevzon A, Lee I, Lei I, Lei J, Lehtimäki T, Lin CF, Ma'ayan A, Marshall CR, McInnes AL, Neale B, Owen MJ, Ozaki N, Parellada M, Parr JR, Purcell S, Puura K, Rajagopalan D, Rehnström K, Reichenberg A, Sabo A, Sachse M, Sanders SJ, Schafer C, Schulte-Rüther M, Skuse D, Stevens C, Szatmari P, Tammimies K, Valladares O, Voran A, Li-San W, Weiss LA, Willsey AJ, Yu TW, Yuen RK, Cook EH, Freitag CM, Gill M, Hultman CM, Lehner T, Palotie A, Schellenberg GD, Sklar P, State MW, Sutcliffe JS, Walsh CA, Scherer SW, Zwick ME, Barett JC, Cutler DJ, Roeder K, Devlin B, Daly MJ, Buxbaum JDDDD Study Homozygosity Mapping Collaborative for Autism; UK10K Consortium. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature. 2014;515:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nature13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bernier R, Golzio C, Xiong B, Stessman HA, Coe BP, Penn O, Witherspoon K, Gerdts J, Baker C, Vulto-van Silfhout AT, Schuurs-Hoeijmakers JH, Fichera M, Bosco P, Buono S, Alberti A, Failla P, Peeters H, Steyaert J, Vissers LE, Francescatto L, Mefford HC, Rosenfeld JA, Bakken T, O'Roak BJ, Pawlus M, Moon R, Shendure J, Amaral DG, Lein E, Rankin J, Romano C, de Vries BB, Katsanis N, Eichler EE. Disruptive CHD8 mutations define a subtype of autism early in development. Cell. 2014;158:263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Van Bon BW, Coe BP, Bernier R, Green C, Gerdts J, Witherspoon K, Kleefstra T, Willemsen MH, Kumar R, Bosco P, Fichera M, Li D, Amaral D, Cristofoli F, Peeters H, Haan E, Romano C, Mefford HC, Scheffer I, Gecz J, de Vries BB, Eichler EE. Disruptive de novo mutations of DYRK1A lead to a syndromic form of autism and ID. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:126–132. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.5. PubMed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.O'Roak BJ, Vives L, Girirajan S, Karakoc E, Krumm N, Coe BP, Levy R, Ko A, Lee C, Smith JD, Turner EH, Stanaway IB, Vernot B, Malig M, Baker C, Reilly B, Akey JM, Borenstein E, Rieder MJ, Nickerson DA, Bernier R, Shendure J, Eichler EE. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012;485:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Murdoch JD, State MW. Recent developments in the genetics of autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Butler MG, Dasouki MJ, Zhou XP, Talebizadeh Z, Brown M, Takahashi TN, Miles JH, Wang CH, Stratton R, Pilarski R, Eng C. Subset of individuals with autism spectrum disorders and extreme macrocephaly associated with germline PTEN tumour suppressor gene mutations. J Med Genet. 2005;42:318–321. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sanders SJ, Murtha MT, Gupta AR, Murdoch JD, Raubeson MJ, Willsey AJ, Ercan-Sencicek AG, DiLullo NM, Parikshak NN, Stein JL, Walker MF, Ober GT, Teran NA, Song Y, El-Fishawy P, Murtha RC, Choi M, Overton JD, Bjornson RD, Carriero NJ, Meyer KA, Bilguvar K, Mane SM, Sestan N, Lifton RP, Günel M, Roeder K, Geschwind DH, Devlin B, State MW. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Grozeva D, Carss K, Spasic-Boskovic O, Parker MJ, Archer H, Firth HV, Park SM, Canham N, Holder SE, Wilson M, Hackett A, Field M, Floyd JA, Hurles M, Raymond FL UK10K Consortium. De novo loss-of-function mutations in SETD5, encoding a methyltransferase in a 3p25 microdeletion syndrome critical region, cause intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM, Bockmann J, Chaste P, Fauchereau F, Nygren G, Rastam M, Gillberg IC, Anckarsäter H, Sponheim E, Goubran-Botros H, Delorme R, Chabane N, Mouren-Simeoni MC, de Mas P, Bieth E, Rogé B, Héron D, Burglen L, Gillberg C, Leboyer M, Bourgeron T. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Genet. 2007;39:25–27. doi: 10.1038/ng1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Willsey AJ, State MW. Autism spectrum disorders: from genes to neurobiology. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015;30:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hamdan FF, Daoud H, Piton A, Gauthier J, Dobrzeniecka S, Krebs MO, Joober R, Lacaille JC, Nadeau A, Milunsky JM, Wang Z, Carmant L, Mottron L, Beauchamp MH, Rouleau GA, Michaud JL. De novo SYNGAP1 mutations in nonsyndromic intellectual disability and autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:898–901. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Deriziotis P, O'Roak BJ, Graham SA, Estruch SB, Dimitropoulou D, Bernier RA, Gerdts J, Shendure J, Eichler EE, Fisher SE. De novo TBR1 mutations in sporadic autism disrupt protein functions. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4954. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Fatemi SH, Earle J, Kanodia R, Kist D, Emamian ES, Patterson PH, Shi L, Sidwell R. Prenatal viral infection leads to pyramidal cell atrophy and macrocephaly in adulthood: implications for genesis of autism and schizophrenia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2002;22:25–33. doi: 10.1023/A:1015337611258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Fatemi SH, Pearce DA, Brooks AI, Sidwell RW. Prenatal viral infection in mouse causes differential expression of genes in brains of mouse progeny: a potential animal model for schizophrenia and autism. Synapse. 2005;57:91–99. doi: 10.1002/syn.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Libbey JE, Sweeten TL, McMahon WM, Fujinami RS. Autistic disorder and viral infections. J Neurovirol. 2005;11:1–10. doi: 10.1080/13550280590900553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Madsen KM, Hviid A, Vestergaard M, Schendel D, Wohlfahrt J, Thorsen P, Olsen J, Melbye M. A population-based study of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination and autism. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1477–1482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Yasuda H, Yoshida K, Yasuda Y, Tsutsui T. Infantile zinc deficiency: association with autism spectrum disorders. Sci Rep. 2011;1:129. doi: 10.1038/srep00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Grabrucker S, Jannetti L, Eckert M, Gaub S, Chhabra R, et al. Zinc deficiency dysregulates the synaptic ProSAP/Shank scaffold and might contribute to autism spectrum disorders. Brain. 2014;137:137–152. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Melke J, Goubran Botros H, Chaste P, Betancur C, Nygren G, Anckarsäter H, Rastam M, Ståhlberg O, Gillberg IC, Delorme R, Chabane N, Mouren-Simeoni MC, Fauchereau F, Durand CM, Chevalier F, Drouot X, Collet C, Launay JM, Leboyer M, Gillberg C, Bourgeron T. Abnormal melatonin synthesis in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:90–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Rossignol DA, Frye RE. Melatonin in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:783–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Tanne JH. Maternal obesity and diabetes are linked to children's autism and similar disorders. BMJ. 2012;344:e2768. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kinney DK, Munir KM, Crowley DJ, Miller AM. Prenatal stress and risk for autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1519–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Miyazaki K, Narita N, Narita M. Maternal administration of thalidomide or valproic acid causes abnormal serotonergic neurons in the offspring: implication for pathogenesis of autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Eskenazi B, Marks AR, Bradman A, Harley K, Barr DB, Johnson C, Morga N, Jewell NP. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in young Mexican-American children. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:792–798. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Larsson HJ, Eaton WW, Madsen KM, Vestergaard M, Olesen AV, Agerbo E, Schendel D, Thorsen P, Mortensen PB. Risk factors for autism: perinatal factors, parental psychiatric history, and socioeconomic status. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:916–925. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]