Abstract

Purpose

To describe factors affecting early intervention (EI) for children who are hard of hearing, we analyzed (a) service setting(s) and the relationship of setting to families' frequency of participation, and (b) provider preparation, caseload composition, and experience in relation to comfort with skills that support spoken language for children who are deaf and hard of hearing (CDHH).

Method

Participants included 122 EI professionals who completed an online questionnaire annually and 131 parents who participated in annual telephone interviews.

Results

Most families received EI in the home. Family participation in this setting was significantly higher than in services provided elsewhere. EI professionals were primarily teachers of CDHH or speech-language pathologists. Caseload composition was correlated moderately to strongly with most provider comfort levels. Level of preparation to support spoken language weakly to moderately correlated with provider comfort with 18 specific skills.

Conclusions

Results suggest family involvement is highest when EI is home-based, which supports the need for EI in the home whenever possible. Access to hands-on experience with this population, reflected in a high percentage of CDHH on providers' current caseloads, contributed to professional comfort. Specialized preparation made a modest contribution to comfort level.

Early identification advocacy efforts were motivated by a goal to prevent the significant language delays that result when hearing loss is not detected until many months, and sometimes years, after birth. An extensive literature describes the development, implementation, and ultimate success of newborn hearing screening programs in the United States (Cone-Wesson et al., 2000; Green, Gaffney, Devine, & Gross, 2007; Kennedy, McCann, Campbell, Kimm, & Thornton, 2005; Morton & Nance, 2006). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) reported that in 2011, 97.9% of all infants born in the United States had their hearing screened. Despite the success of screening programs, providing all families with timely access to early intervention (EI) services that meet their needs and result in the prevention of speech and language delays remains an ongoing challenge.

To gain a better understanding of the variables influencing outcomes of children who are deaf or hard of hearing (CDHH), the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders convened a working group in 2006. The group compiled a comprehensive list of potential sources of variance that might account for individual differences in outcomes. Intervention was identified as one source of variance (Eisenberg et al., 2007). The authors noted that research on the impact of specific aspects of intervention, including family involvement, setting, and provider skill (among other aspects), is lacking. These variables are explored in the current work.

Family Involvement

The positive effect of family involvement in EI services on language outcomes has been described. Moeller (2000) studied language outcomes of children at age 5. After controlling for level of hearing and age of entry into EI services, level of family involvement in EI explained the most variance. In 2004, Spencer investigated language performance in a group of children who received cochlear implants before their third birthday. Age of implantation and family involvement were the two variables associated with differences in language outcomes. Watkin et al. (2007) reported that teacher ratings of parents' level of involvement and the language outcomes of their children were strongly correlated. A compelling finding was that when two groups of children with later-confirmed hearing losses were compared, those with highly involved families had higher speech and language scores than those with families who were less involved. The investigators concluded that a high level of family involvement can mitigate the consequences of later identification. Sarant, Holt, Dowell, Rickards, and Blamey (2009) studied spoken language outcomes in a group of preschool children, over half of whom had poor language outcomes. Analyses showed degree of hearing loss, cognitive ability, and family participation as measured using Moeller's scale for family involvement (2000), predicted language outcomes and accounted for almost 60% of the variance in scores. Although a strong positive relationship between family involvement and child language outcomes has been described by multiple investigators, factors such as the setting where EI services are provided or skills of the provider that might affect a family's involvement in EI services have yet to be studied.

Provider Skill

Provider skill has also been cited as a potential contributor to outcomes. Professionals with a wide range of disciplinary backgrounds provide EI to families and their CDHH (Stredler-Brown & Arehardt, 2000). Certification standards are mandated by organizations such as the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), the National Association for the Education of Young Children, and the Council for Exceptional Children. These standards vary, but rarely require preservice coursework or practicum focused on the specific needs of young CDHH (Chandler et al., 2012; Council for Clinical Certification in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2014; Council for Exceptional Children, 2004; National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2009; Sandall, Hemmeter, Smith, & McLean, 2005).Teachers of CDHH are educated in programs specific to hearing loss, but depending upon their program's focus may or may not acquire skills and knowledge to support early spoken language development. As a result, preparation of EI professionals to meet the unique needs of children with hearing loss may vary across the educational backgrounds of the providers and the resources available to them (Marge & Marge, 2005; Meadow-Orlans, Mertens, & Sass-Lehrer, 2003).

The 2007 Joint Committee on Infant Hearing position statement included guidelines regarding early detection of hearing loss and provision of EI services and stated, “All individuals who provide services to infants with hearing loss should have specialized training and expertise in the development of audition, speech and language” (American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, 2007, p. 8). A Supplement to the Position Statement focused on EI and described the knowledge and skills providers should have to meet the needs of this diverse population (Muse et al., 2013). A technical report jointly issued by ASHA and the Council on the Education of the Deaf stated that best outcomes for children occur when professionals from a core team from audiology, education of the deaf, and speech-language pathology work collaboratively with families (ASHA, 2008). Although these documents highlight the overarching principles and goals in early identification and intervention, they are based upon a consensus of members from multiple professions and stakeholders and represent a relatively low level of evidence. A diverse panel of experts, including parents, deaf professionals, EI specialists and program leaders, and researchers, identified 10 essential guidelines for family-centered EI, regardless of communication modality (Moeller, Carr, Seaver, Stredler-Brown, & Holzinger, 2013). The panel included evidence-based resources to identify, train, and support EI professionals; however, it is not known whether EI professionals are prepared to support the specific needs of subgroups of CDHH, such as young children who are hard of hearing. It is also unclear whether experience with this population of children leads to increased confidence and skill in completing specialized tasks.

Factors other than preprofessional preparation, such as years of experience, types and intensity of professional experience, or continuing education, may also influence the degree to which individuals are both comfortable and competent providing specific EI services. Across professional disciplines, literature regarding experience, type, or intensity of caseload and their potential relationship with comfort in performing specialized tasks is scarce. However, the relationship between confidence, which is referred to here as comfort, and hands-on mentored practice has been studied in a variety of professional and clinical contexts. The model of coaching and mentoring professionals by knowledgeable colleagues has been adopted from business by numerous professions as a means of developing skills and motivating both employees and students (Darling-Hammond, Wei, Andree, Richardson, & Orphanos 2009). In nursing, the relationship between self-reported levels of confidence and competency has been explored by numerous investigators (Farrand, McMullen, Jowett, & Humphreys, 2006; Freiburger, 2002; Ulrich et al., 2010). These studies found that students or graduates who had opportunities to engage in mentored, hands-on clinical experiences reported higher levels of self-confidence and higher levels of observed and/or self-reported competency performing specific tasks compared with those who did not. Medical students reported that the most important factor contributing to increased confidence was mentored, hands-on clinical practice (Harrell, Kearl, Reed, Grigsby, & Caudill, 1993). In addition to mentoring, it may be that hands-on experience gained by having regular contact with a number of CDHH on one's caseload also leads to increased confidence in specific skill areas. This hypothesis is explored in the current study.

The need for well-prepared EI providers has been exacerbated by the success of newborn hearing screening, which resulted in earlier identification of CDHH, especially those with mild to moderate hearing loss, who previously had not been identified until after 2 years of age (Harrison & Roush, 1996; Harrison, Roush, & Wallace, 2003). The demographic shift that occurred in an EI program in Kansas between 2002 and 2006 is representative of changes occurring across the country. Following implementation of newborn hearing screening, the number of CDHH enrolled in EI doubled, the average age at enrollment decreased from 12 to 3.7 months, and children with mild to moderate hearing loss were enrolled in numbers equal to those in the severe and profound range (Halpin, Smith, Widen, & Chertoff, 2010).

Current Evidence Regarding Children With Hearing Loss

Recent studies provide evidence-based guidance regarding some of the factors that predict better speech and language outcomes among young CDHH, including early and well-fit hearing aids (McCreery, Bentler, & Roush, 2013; McCreery et al., 2015; Tomblin, Harrison et al., 2015), consistent use of well-fit hearing aids (Walker et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2015), and access to an auditory environment with high-quality parental language input (Ambrose, Walker, Unflat-Berry, Oleson, & Moeller, 2015). Although hearing aid fitting is specifically within the audiologists' scope of practice, families also turn to EI professionals with questions on hearing aid use and management skills (Muñoz & Blaiser, 2011). Thus, EI providers must have the skills to solve problems with, and support families of, young children to achieve consistent use of these devices during a period of time when that goal is particularly challenging (Walker et al., 2013). They must also be able to coach families to provide the highest quality language environment possible. As DesJardin and Eisenberg (2007) concluded in their study of language outcomes in children with cochlear implants, incorporating goals to enhance families' involvement, linguistic input, and self-efficacy is essential to supporting better language outcomes. In 2013, these two investigators and colleagues (Stika et al., 2015) examined child and parent factors associated with the developmental outcomes of a group of early-identified children with mild to severe hearing loss. The results underscored the importance of maternal self-efficacy in achieving positive developmental outcomes for their children. Their work did not attempt to link maternal self-efficacy to the EI professional's preparation or skills. Although the current work will not answer the question of whether or not professional skill and confidence can increase parental self-efficacy, it is a first and essential step in exploring the possibility of a relationship between the two.

The complex relationship among the many variables involved in EI has been a barrier to research. As a result, the overarching topic of early services is underrepresented in the literature regarding children with all degrees of hearing loss. We are unaware of any studies linking service location to parental involvement or of studies that examine aspects of professionals' preparation, caseload composition, and years of experience in relation to their comfort with providing specific services. The current study is designed to address these research gaps.

Research Questions

This study examines two of the EI variables identified by Eisenberg et al. (2007) as important influences on outcomes for children and families. Variables considered in the current study include, (a) parental involvement as a function of setting (home vs. not in the home), and (b) preparation, caseload composition, and experience of the provider. Our research questions are indicated below.

Where are EI services for children who are hard of hearing delivered across the birth-to-three year period?

What is the effect of setting on family participation?

What is the preprofessional and professional preparation of the individuals who provide EI services to children who are hard of hearing between the ages of birth-to-three years?

Do the background factors of professionals' preparation, caseload composition, and/or experience relate to self-confidence in specific EI skills?

Method

The Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss (OCHL) study is a 5-year, multicenter investigation designed to characterize the developmental, behavioral, and familial outcomes of children with mild to severe hearing loss and to explore how variations in child and family factors and intervention characteristics relate to functional outcomes. The children had a permanent bilateral hearing loss, with better ear pure tone averages (BEPTA) at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz between 25 and 75 dB hearing loss (HL). Children across the entire inclusion range (25–75 dB HL) were enrolled in the OCHL study; however, a majority of the children had BEPTAs between 45 and 65 dB HL. None had additional significant sensory or developmental challenges and all had at least one primary caregiver who spoke English in the home. The current study involves a subgroup of parents and EI professionals of 122 children ranging in age from 6 to 36 months at study entry, who were enrolled in the OCHL study and followed prospectively. The children's mean BEPTA was 51.65 dB HL, (SD = 13.04). The research team made exceptions to include five children with BEPTAs outside the criterion range due to unique audiological or medical circumstances (e.g., hearing loss in low or high frequencies only, fluctuation due to otitis media with effusion, or enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome). This carefully described cohort was recruited in an attempt to isolate the effects of hearing loss on outcomes without the confounding effects of comorbid conditions or lack of exposure to English at home. Families were recruited and seen in the home states of the three research teams (Iowa, Nebraska, and North Carolina), as well as at cooperating sites in neighboring states. Infants and toddlers were seen every 6 months until 24 months of age and annually thereafter. Trained study personnel conducted all assessments. Approval was obtained from the institutional review board at each research center. A description of the overall OCHL study design and epidemiological information can be found in Holte et al. (2012).

Adult Participants

Two groups of adult respondents participated. The first group was composed of 122 parents or primary caregivers of children enrolled in the study. As seen in Table 1, 89.4% of the mothers had at least a high school diploma or equivalent and nearly half (45.1%) had earned a bachelor's degree or higher. The 2012 census reported that 30.6% of women over the age of 25 had completed a bachelor's degree (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). The bias toward higher levels of education among the mothers of children in the OCHL study is typical in research that involves volunteers (Holden, Rosenberg, Barker, Tuhrim, & Brenner, 1993). Slightly more than two thirds of the families reported that their household income was more than $40,000 annually. Although the families participating in the OCHL study represented a wide range of maternal education and family income levels, the sample was skewed in the direction of well-educated and well-resourced families.

Table 1.

Description of participating families with children who are deaf and hard of hearing (CDHH; n = 122) and selected background characteristics of the children.

| Demographic and background characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Highest educational level completed | ||

| Some high school or less | 3 | 2.5 |

| Completed high school or equivalent (GED) | 18 | 14.8 |

| Postsecondary education | 36 | 29.5 |

| College graduate | 31 | 25.4 |

| Postgraduate work | 24 | 19.7 |

| Undisclosed | 10 | 8.2 |

| Household income level | ||

| <$20,000 | 12 | 9.8 |

| $20,001–$40,000 | 15 | 12.3 |

| $40,001–$60,000 | 27 | 22.1 |

| $60,001–$80,000 | 23 | 18.9 |

| $80,001–$100,000 | 14 | 11.5 |

| >$100,000 | 20 | 16.4 |

| Undisclosed | 11 | 9.0 |

| CDHH gender | ||

| Male | 67 | 54.9 |

| Female | 55 | 45.1 |

| CDHH ethnicity | ||

| White | 104 | 85.2 |

| African American | 8 | 6.6 |

| Asian-Pacific | 3 | 2.5 |

| Multiracial | 3 | 2.5 |

| Other | 2 | 1.6 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 | 0.8 |

| Undisclosed | 1 | 0.8 |

| Timing of identification | ||

| HL identified at newborn screen | 110 | 90.2 |

| HL identified later | 12 | 9.8 |

Note. GED = general educational development; HL = hearing loss.

The second group of adult participants was composed of the families' EI professionals (n = 131) who were asked to complete an online questionnaire each year they provided services to a family enrolled in the study. They will be described in the results section.

Questionnaires

In addition to the standardized and nonstandardized instruments administered to participating children (Tomblin, Walker, et al., 2015), several questionnaires were designed and tailored to elicit a wide range of information from families and professionals.

Family Interview Questionnaire

The National Early Intervention Longitudinal Study Interview (SRI International, 2000) was the basis for the Family Interview questionnaire that was created. However, extensive changes were made to tailor the interview for the OCHL families. The Family Interview was composed of sections with questions regarding (a) household characteristics, (b) current EI services, (c) caregiver impressions of EI services, (d) additional services, (e) child care, (f) child's disposition, and (g) sources of parent support (the Family Interview is available at http://ochlstudy.org/pdf/OCHL%20Family%20Interview%20Birth-3.pdf). A research assistant, who is a parent of children who are deaf, conducted all the interviews by telephone. The Family Interview, lasting approximately an hour, was completed with the parent or caregiver and was scheduled approximately 6 months after each child's yearly study visit. The number of surveys collected for each child varied depending on the timing of the initial survey and number of subsequent study visits prior to aging out of EI services. Although children aged out of EI services on their third birthday, two families participated in an interview as much as 6 months later. Each report of the Family Interview was allocated to one of three specific time periods in the children's lives: infant (9 to 11 months), toddler (12 to 23 months), and preschool (24 to 42 months). Some families completed more than one Family Interview, however, only one response per family occurred in each age group, and therefore, analyses involving partitioned age groups were not influenced by multiple reports.

Early intervention settings and family participation. Age groups of children were further segmented into subcategories, based upon the setting where EI services were delivered. The settings were described as home, day care center, center for children with special needs, specialized center for children with hearing loss, and therapist or clinic office. Parents were asked how often they were able to participate with their child and the EI provider at each setting. Response choices were: always, most of the time, about half the time, some of the time, not very often, and never.

Service Provider Questionnaire: Birth-to-Three Version

The Service Provider Questionnaire was designed as an online instrument and was completed annually by each child's service professional(s). Parents completed an annual release form to grant the OCHL team permission to contact service provider(s). Only those professionals who provided services specifically related to the child's hearing were asked to complete the questionnaire. Audiologists who provided services related to assessment and management of hearing aids completed a separate questionnaire. Those results will be reported in other articles. Three EI providers who also held audiology credentials did complete the Service Provider Questionnaire.

The Service Provider Questionnaire consisted of six sections: (a) characteristics of services provided to a family (e.g., type, frequency, setting, and family participation), (b) caseload characteristics, (c) provider preparation, (d) professional experience and confidence in providing services in specific skill areas, (e) family-centered EI practices, and (f) hearing aid and frequency-modulated amplification system (FM) use. Service providers were mailed or e-mailed a link to the instrument and received a $15.00 gift card when it was completed. In total, 131 unique providers submitted at least one questionnaire. Some families received intervention services from more than one provider, resulting in more than one questionnaire being completed per family in a year. In addition, a few professionals provided services to more than one child participating in the OCHL study. The issue of multiple reports was addressed according to the item under analysis. For example, questions regarding the professionals, such as caseload or educational preparation, were filtered so that each service provider was included only once. The information presented here is based upon the last questionnaire each EI professional completed. The last report was selected so that credit was given for any degrees, certification, or continuing education completed while EI services were provided to an OCHL family.

Provider preparation. Responses to four questions in the Service Provider Questionnaire related to preparation and experience were assigned weighted scores to reflect their proximity to best practice (close/far) and level of specialized preparation (highest/lowest). It is important to stress that these scores reflect preparation to work with CDHH and are not intended to reflect the value of any degree, degree area, or profession. Scores were based solely upon the information provided by the professionals responding to the Service Provider Questionnaire. Thus, it is possible that providers who underreported their credentials, or vice versa, are not accurately represented.

A team composed of a biostatistician and five others with multiple (2–30) years of clinical experience serving CDHH and their families generated and/or reviewed the scales for each question included in the specialization score. Each question was given a rating scale that contributed an appropriate weight to the overall specialization score. Responses to three questions regarding highest degree earned, degree area(s), and certification(s) were scored on a scale of 0 to 5. Continuing education was scored on a scale of 0 to 2. The rationale for the limited range for this question was that the question format made it challenging to judge the quality and quantity of reported continuing education. In addition, in some cases continuing education may have contributed to earning an additional certification. Giving that item less weight reduced its influence on the total score of each respondent.

Explanation of scoring. Scoring for the highest degree earned was based upon the assumption that the depth and breadth of knowledge and skill would increase incrementally with each advancing degree. A bachelor's degree received a score of one, a master's degree received a score of three, and a doctoral degree received a five. Two EI providers reported an education specialist degree (EdS). Although this degree is earned after receiving a master's degree, it is associated with a variety of post-master's programs, not necessarily associated with hearing loss, and received a score of three.

Each degree area represented by at least one respondent was assessed based upon whether or not it was likely to involve coursework or practicum that provided skills and knowledge to support families in providing a rich language environment, understanding the importance of consistent access to audition to support speech and language development, assessing hearing aid function, and maximizing use for infants and toddlers. Respondents with a degree in speech-language pathology (SLP) or teaching children who are deaf and hard of hearing (TODHH) that included specialized preparation in developing listening and spoken language received a score of 5. Some respondents had combinations of bachelor's and master's degrees in areas that together offered an array of desired knowledge and skills. These combinations included SLP plus audiology, TODHH plus SLP, and TODHH plus audiology; each of these combinations received a score of 4. A degree in either SLP or TODHH received a score of 3. Although SLPs have a strong background in typical language development and a wide range of language and speech disorders, the requirements regarding knowledge and skills in the area of childhood hearing loss are minimal. Most meet the competency requirement for certification by taking an introductory audiology class and/or aural rehabilitation course that covers a wide range of topics including instrumentation and aural rehabilitation for adults. A small number of SLP graduate programs offer specialized courses and clinical experiences to prepare students to provide early services to CDHH and their families (Houston & Perigoe, 2010; Roush et al., 2004; Watson & Martin, 1999). Until recently, only a few TODHH programs focused on knowledge and skills related to the development of listening and spoken language (White, 2006).

A degree in audiology, which received a score of 2, prepares students to assess and diagnose hearing loss, fit hearing aids, and manage assistive technology; however, there is little if any content regarding child language development. These skills support consistent access to the auditory signal, but do not necessarily serve to support the family in regard to the child's speech and language development. Early childhood education and early childhood special education degrees were scored as 2, given their focus on development of the young child in the family context. A degree in special education received a score of 1. Although there may be special education programs that provide an emphasis in hearing loss, this degree typically has a broad focus on high incidence disabilities, such as developmental delays and learning disabilities, among school age children. Content related to children's speech and language development, hearing aid use and management, or providing a rich language environment is not typically part of a degree program in this area.

Certification was scored on a 1 to 5 point scale. Certifications earned in association with a related degree did not receive any additional points. For example, an SLP did not receive points for having certification in that area. However, if an additional certification such as TODHH was held by an SLP, additional points were awarded. The additional certification earning the highest number of points (5) was Listening and Spoken Language Specialist. These certified professionals must demonstrate a range of core competencies through 80 hours of postdegree continuing education, including a minimum of 44 sessions with a certified mentor, and completion of 900 hours providing auditory–verbal therapy. These requirements take between 3 and 5 years to complete.

Three categories of certification received a score of 3. Hanen training is a nationally recognized and well-defined family-focused early language learning program that prepares EI professionals to support parents in providing an optimal environment for language development. However, the training is not specific to the unique needs of CDHH and their families. PIT-STOP certification from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln is postdegree certification that provides three courses in early childhood development for those who have certification as a TODHH, but who lack EI preparation. Certification as a TODHH was earned as an additional certification by EI providers either pre- or postdegree. Council on Education of the Deaf certification standards are linked to the Council for Exceptional Children standards and the broad competencies that are required of graduates of those programs.

Early intervention/birth–kindergarten and other similar designations, such as state certification in EI, received a score of 2. Providers with this certification have met state-approved or recognized certification for assessment, evaluation, and provision of EI services. Certification requirements vary by state and are typically not disability-specific. A response category of other was provided for respondents who held certifications that might be relevant but were not included in the options listed. No one selected that category.

Continuing education was scored on a 0 to 2 point scale. EI providers were asked, “What professional education have you had concerning children who are deaf or hard of hearing? (check all that apply).” Response options included none, half-day in-service, day-long workshop or short course, 1 to 2 weeks of specialized instruction, semester-long course, and other (please specify). Participation in a 1- or 2-week intensive course or semester-long course received a score of 2. A half to full day of in-service received a score of 1.

Statistical Analyses

Most of the data collected from these surveys were categorical. After validating statistical assumptions, a Pearson chi-square test of independence was used to test the independence between the two categorical variables, location of EI services, and parent participation. The ordinal and continuous variables consisted of comfort scores, caseload composition, years of experience, and specialization score. Pearson correlation was generally used between continuous or ordinal variables. However, because some of the data are ordinal, the Pearson correlations and p-values were compared to the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for non-zero correlation, which is designed to test for correlation between ordinal variables. For variables that could be classified as continuous or ordinal, such as specialization score, both Pearson correlation and the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for non-zero correlation were applied. The p-values were nearly identical between the continuous and ordinal methods, and we reported the Pearson's correlation results.

All significance tests were evaluated at the standard .05 level of significance. In this article, we do not report any multiplicity of testing adjustments. Studies usually manage type I error by setting the significance level to .05. However, relationships with specialization scores are complex and nuanced because of the multiple computational factors involved. Thus, we are equally concerned with type II error because lower type II error rates would allow more potential explanatory variables to be identified. Because the relationship between type I and type II error rates is such that an increase in the probability of a type I error translates to a reduction in the probability of a type II error, using a level of significance lower than 0.05 in exploratory studies increases the likelihood of overlooking a potentially important association.

Results

Early Intervention Settings and Family Participation

The data reported in this section are based upon information from Family Interview questionnaires (n = 191) regarding the settings in which EI services were delivered and how frequently a family member was able to participate in those services. However, one family reported no services after their child's first birthday, and seven families reported no services after 24 months, resulting in 183 reports regarding service setting and family involvement. Table 2 displays the level of family participation by age group and setting in which services were delivered

Table 2.

Family participation by service setting.

| Participation (%) |

Never | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | Age (months) | n | Always | Most of the time | About half the time | Some of the time | Not very often | |

| Home | ||||||||

| 9–11 | 13 | 69.2 | 15.4 | 7.7 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 0.0 | |

| 12–23 | 66 | 89.4 | 6.1 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | |

| 24–42 | 86 | 88.4 | 8.1 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 | |

| Day care | ||||||||

| 9–11 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | |

| 12–23 | 10 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 80.0 | |

| 24–42 | 15 | 13.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 80.0 | |

| Center-based | ||||||||

| 9–11 | 0 | |||||||

| 12–23 | 3 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 0.0 | |

| 24–42 | 15 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 6.7 | 53.3 | |

| Office or clinic | ||||||||

| 9–11 | 0 | |||||||

| 12–23 | 5 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 24–42 | 7 | 71.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 28.6 | |

Services in the Home

Across the years during which EI services were received, the majority of respondents (68.9%, n = 126) reported that services were delivered solely in the home. Among these families, the proportion of home-based-only services decreased across the respective age categories; 85.7% (n = 12) of infants, 74.7% (n = 53) of toddlers, and 62.2% (n = 61) of preschoolers received all of their EI services in the home. Across all ages, level of family member participation with their child and EI professional was described as always or most of the time for 95.2% of families receiving services in the home. None of the families reported never participating in home-based services.

Services Outside of the Home

Eighteen families (9.8%) reported that EI occurred only in a nonhome setting and 21.3% (n = 39) stated that they had received services in both home and nonhome settings within the year of the Family Interview. Services in nonhome settings were provided in day care, centers for children with special needs, specialized centers for children with hearing loss, and therapist's offices or clinics. Families reported that 14.8% (n = 27) of children received at least some EI services in a day care setting. Due to the small number of children receiving intervention in a center for children with exceptional needs (multicategorical setting), two response options—center for children with exceptional needs (n = 3) and specialized centers for CDHH (n = 15)—were grouped into one category called Center-Based Services. This grouped category accounted for 9.8% of the responses. Twelve children (6.6%) received services in a clinic or therapist's office.

Compared with home-based settings, family level of participation was more variable for services outside of the home. When services were delivered in nonhome locations, including day care, center-based or a therapist's office or clinic, less than 30% of the parents described their participation as always or most of the time. Of the nonhome locations, family participation was more frequently rated always or most of the time for the therapist office or clinic setting. The greatest proportion of EI services provided outside the home was in a day care setting. Among these families, only 7.7% (n = 2) of the parents described their level of participation as always or most of the time. Table 2 summarizes differences in family involvement in sessions when services are provided at home in contrast to outside the home.

When EI service settings were collapsed into two categories, at home and not at home, and responses were simplified into three categories, always, some of the time, and not very often or never, a Pearson chi-square test of independence showed a significant relationship between setting and parent participation in intervention services (χ2 = 112, p < .001), indicating that family participation was significantly more likely to occur when services were delivered in the home.

Description of Professionals Providing Early Intervention Services

The information reported in this section is based upon the last response during the birth-to-three period of 131 EI professionals to an annual online questionnaire.

Caseloads and Experience Within Early Intervention

Both size and make-up of individual provider's caseloads varied widely. Caseload sizes ranged from as few as one to as many as 60 children. The average total caseload was 20 children (M = 19.5, SD = 12.6). Slightly more than half of the respondents (53%, n = 70) reported caseloads composed entirely of children with some degree of hearing loss. In contrast, 27% (n = 35) of early service providers reported that children with any degree of hearing loss made up less than 20% of their total caseload. Number of years of experience providing EI services ranged from less than 1 to 37 years (M = 12.5, SD = 10.2).

Highest Degree and Degree Areas

Among this group, 18.5% had a bachelor's degree, 80% had earned a master's degree (MA or MS), and two providers (1.5%) had a doctoral degree. Slightly more than half had a degree as a TODHH and one third earned degrees in SLP. The remainder had degrees in a variety of areas, only one of which was unrelated to working with children. A complete description appears in Table 3.

Table 3.

Preparation of early intervention professionals (n = 131).

| Preparation | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Degree level by discipline | ||

| TODHH | ||

| Bachelor's | 19 | 14.5 |

| Master's | 52 | 39.7 |

| SLP | ||

| Master's | 41 | 31.3 |

| PhD | 2 | 1.5 |

| ECSE | ||

| Bachelor's | 4 | 3.1 |

| Master's | 8 | 6.1 |

| Audiology | ||

| Master's | 4 | 3.1 |

| AuD | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unrelated degree | ||

| Bachelor's | 1 | 0.8 |

| Degree area | ||

| SLP + specialized HL focus | 6 | 4.6 |

| TODHH + specialized HL focus | 1 | 0.8 |

| SLP + audiology | 2 | 1.5 |

| TODHH + audiology | 1 | 0.8 |

| TODHH + counseling | 2 | 1.5 |

| SLP | 37 | 28.2 |

| TODHH | 68 | 51.9 |

| Audiology | 1 | 0.8 |

| ECSE | 10 | 7.6 |

| EC | 2 | 1.5 |

| Human services | 1 | 0.8 |

| Additional certification | ||

| LSLS/AVT | 9 | 6.9 |

| TODHH | 2 | 1.5 |

| PITSTOP | 1 | 0.8 |

| ECSE or EC | 27 | 20.6 |

| EI | 4 | 3.1 |

| No additional | 88 | 67.2 |

Note. TODHH = teacher of children who are deaf and hard of hearing; SLP = speech-language pathology; PhD = Doctorate of Philosophy; ECSE = early childhood special education; AuD = Clinical Doctorate in Audiology; HL = hearing loss; EC = early childhood; LSLS/AVT = listening and spoken language/auditory verbal therapy; EI = early intervention.

Certifications

With the exception of the individual who did not earn a degree in an area related to hearing loss or EI, all the professionals were certified in their degree area. In addition to their degree-related certifications, 33% (n = 43) reported holding additional certifications earned either during their college or university education or following graduation. College and university programs in TODHH are sometimes located within programs of Special Education; thus, almost a quarter (21%) of those with a degree in TODHH simultaneously earned certification in early childhood education or early childhood special education. Sixty-seven percent of the EI providers held no additional certifications.

Professional Development and Continuing Education

When queried about continuing education or professional development specifically related to CDHH, 61% (n = 80) indicated they had participated in relevant continuing education. Twenty-two participated in a half- or full-day in-service training. Two EI providers had 1 to 2 weeks of intensive, specialized instruction, and 56 reported a semester-long course or more.

Specialized Preparation

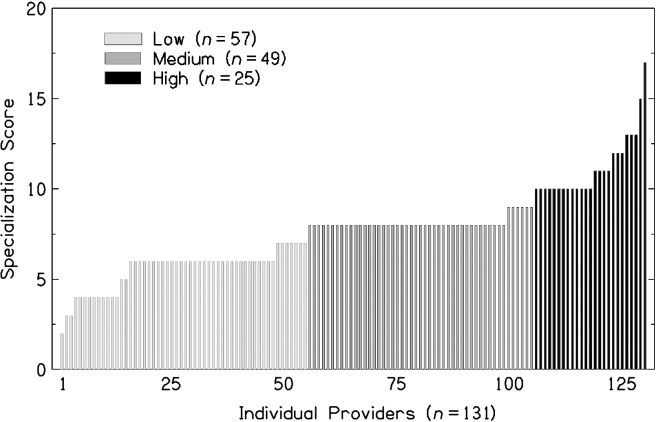

A total score comprising the weighted responses to the degree level, degree area, certifications, and professional and continuing education questions was calculated for each provider. Scores were based upon the extent to which each item contributed to knowledge and skills that have been identified as supporting positive speech and language outcomes. The potential range of scores is from 1 to 17, with a higher number representing higher specialization. As seen in Figure 1, scores ranged from a total of 2 to a total of 17. The scores of the respondents clustered into three relatively homogenous groups in terms of provider preparation, as described below. Therefore, the provider characteristics underlying the weighted scores were used as a tool to separate providers into categories of low, medium, or high specialization scores. 1

Figure 1.

Early intervention professionals' specialization scores.

Scores of seven or less 43.5% (n = 57) typically reflect providers who had earned a bachelor's degree (n = 21) or a master's (n = 36) but held no certifications in addition to that associated with their degree. In this group, 55 of the 57 providers did not report any continuing professional education related to working with CDHH. Individuals in this group are categorized as having a low level of specialized preparation.

Thirty-seven percent (n = 49) of the respondents had a provider specialization score of 8 or 9 and were classified as having a medium level of specialization. All but four professionals in this range had earned a master's degree in TODHH or SLP, three had a bachelor's degree in TODHH, and two had a doctorate in SLP. Providers in this group were likely to have participated in continuing education related to childhood hearing loss and/or had been certified in an additional area. Twenty-five (19.1%) EI professionals with composite scores between 10 and 17 comprised the group representing a high level of specialized preparation. They had at least one master's degree, usually at a program emphasizing childhood hearing loss. All had additional certifications and continuing education experiences. The EI provider with the highest score had a doctorate and multiple additional certifications including Listening and Spoken Language Specialist.

Provider Self-Assessment of Comfort Level

Although the design of the study did not support direct evaluation of the EI providers' skills, each respondent was asked to indicate their levels of comfort on 18 skill areas associated with providing services to young CDHH. The skill areas were identified by professionals with experience providing services to CDHH and their families as relevant knowledge and skills necessary to develop listening and spoken language. Early intervention providers rated their comfort level on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (no comfort) to 4 (high level of comfort). Nearly all of the responses ranged between 2 and 3, regardless of respondents' specialization group. The primary exception was the item developing sign language skills; responses across all groups were below 2, indicating a low level of comfort with helping the family develop sign language skills with their child. As shown in Table 4, when comfort scores of the three groups are averaged, all scores with the exception of two—developing sign language skills and troubleshooting hearing aids—ranged between 3.16 and 3.75.

Table 4.

Self-reported comfort levels (scale 0–4) by specialization group (low, medium, high).

| Specialization group |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skill area | Low |

Medium |

High |

Grand means |

||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Assessing speech | 2.94 | 0.79 | 3.37 | 0.56 | 3.49 | 0.58 | 3.21 | 0.71 |

| Assessing language | 3.36 | 0.77 | 3.67 | 0.46 | 3.71 | 0.46 | 3.55 | 0.63 |

| Assessing communication approach | 3.30 | 0.67 | 3.62 | 0.54 | 3.68 | 0.46 | 3.49 | 0.61 |

| Designing therapy goals | 3.42 | 0.61 | 3.67 | 0.48 | 3.80 | 0.42 | 3.60 | 0.53 |

| Promoting language in routines | 3.58 | 0.67 | 3.76 | 0.43 | 3.81 | 0.38 | 3.69 | 0.55 |

| Building language through play | 3.66 | 0.50 | 3.79 | 0.41 | 3.85 | 0.35 | 3.75 | 0.44 |

| Expanding vocabulary | 3.62 | 0.54 | 3.76 | 0.43 | 3.85 | 0.35 | 3.72 | 0.48 |

| Developing oral language | 3.23 | 0.65 | 3.48 | 0.55 | 3.63 | 0.47 | 3.40 | 0.60 |

| Developing sign language | 1.69 | 0.99 | 1.90 | 1.12 | 1.48 | 0.88 | 1.73 | 1.03 |

| Promoting early literacy | 3.35 | 0.72 | 3.56 | 0.51 | 3.67 | 0.56 | 3.49 | 0.63 |

| Carryover of speech therapy | 3.28 | 0.64 | 3.47 | 0.57 | 3.49 | 0.63 | 3.39 | 0.62 |

| Carryover of language therapy | 3.52 | 0.65 | 3.67 | 0.47 | 3.67 | 0.47 | 3.60 | 0.56 |

| Inserting earmolds | 3.13 | 1.11 | 3.47 | 0.78 | 3.75 | 0.72 | 3.38 | 0.95 |

| Promoting hearing aid checks | 3.07 | 1.07 | 3.37 | 0.88 | 3.69 | 0.74 | 3.30 | 0.96 |

| Using Ling sounds | 2.97 | 1.19 | 3.26 | 1.01 | 3.76 | 0.72 | 3.23 | 1.08 |

| Troubleshooting hearing aid | 2.78 | 1.13 | 3.01 | 0.91 | 3.30 | 0.84 | 2.97 | 1.07 |

| Using FM | 3.00 | 1.15 | 3.24 | 0.84 | 3.36 | 0.85 | 3.16 | 0.99 |

| Developing listening skills | 2.97 | 0.98 | 3.23 | 0.82 | 3.52 | 0.77 | 3.17 | 0.90 |

Note. FM = Frequency-modulated amplification system.

Relationships of Caseload Composition and Experience to Provider Comfort

Results showed significant relationships between the percent of CDHH on a professional's caseload and self-reported comfort with each skill except developing sign language. As can be seen in Table 5, eight skills were strongly correlated with caseload composition (r range = .41–.80; p < .0001), six of which related to hearing aid use and management and promoting listening skills. Nine other skills weakly to moderately correlated with caseload composition (r range = .16–.37; p < .02).

Table 5.

Pearson correlations representing the relationships of self-reported comfort scores in each skill area with years of experience, caseload composition, and specialization levels.

| Skill area | Years of experience |

Caseload composition

a

|

Specialization levels |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| Assessing speech | .12 | .073 | .20 | .003 | .32 | < .001 |

| Assessing language | .23 | .001 | .37 | < .001 | .24 | .008 |

| Assessing communication approach | .14 | .047 | .41 | < .001 | .27 | .003 |

| Designing therapy goals | .12 | .367 | .31 | .018 | .28 | .053 |

| Promoting language in routines | .19 | .005 | .32 | < .001 | .17 | .049 |

| Building language through play | .21 | .002 | .24 | < .001 | .17 | .057 |

| Expanding vocabulary | .22 | .001 | .28 | < .001 | .19 | .029 |

| Developing oral language | .18 | .011 | .33 | < .001 | .26 | .003 |

| Developing sign language | .06 | .380 | −.02 | .732 | −.04 | .672 |

| Promoting early literacy | .12 | .084 | .53 | < .001 | .20 | .023 |

| Carryover of speech therapy | .13 | .055 | .16 | .002 | .14 | .119 |

| Carryover of language therapy | .25 | < .001 | .34 | < .001 | .12 | .186 |

| Inserting earmolds | .11 | .103 | .72 | < .001 | .25 | .005 |

| Promoting hearing aid checks | .11 | .111 | .74 | < .001 | .24 | .007 |

| Using Ling sounds | .08 | .230 | .80 | < .001 | .26 | .003 |

| Troubleshooting hearing aid | .09 | .203 | .76 | < .001 | .19 | .033 |

| Using FM | .07 | .300 | .63 | < .001 | .14 | .107 |

| Developing listening skills | .16 | .019 | .69 | < .001 | .23 | .010 |

Note. FM = Frequency-modulated amplification system. Years of experience and caseload composition are continuous variables. Specialization levels are categorical variables.

Percentage of children who are deaf or hard of hearing on caseload.

Comfort scores related to five skills associated with developing language (assessing language, promoting language in routines, building language through play, expanding vocabulary, and carryover of language therapy) were weakly correlated (r range = .19–.25; p < .01) with providers' years of EI experience, as were three others (assessing communication approach, developing oral language, and developing listening skills; r range = .16–.37; p < .02). The remaining nine items were not significantly correlated with provider experience.

Relationship of Specialized Preparation to Provider Report of Comfort

Self-reported comfort scores were also correlated with provider specialization (low, medium, or high). As shown in Table 4, when providers' comfort levels were considered by specialization group, weak but significant correlations were found between comfort levels and specialization scores on 12 of the 18 variables (r = .17–.27; p = .05). The only comfort level moderately correlated with specialization was assessing speech skills, with an estimated correlation of r = .318.

It is the case that the reported comfort levels for the 18 skill areas have a large correlation with each other. In fact, the pairwise correlations are generally between .40 and .80 (all highly significant) except for developing sign language skills, which is not significantly correlated with the comfort level of any the other skills. A principal components analysis (PCA) was performed to identify the redundancies that exist within the data. The first principal component explains 59% of the variance in the measures, and the loadings of each skill—apart from developing sign language skills—were nearly identical, which suggests that a simple average of the skills yields the best overall summary of provider comfort. The second principal component identified a subgroup of items that explain 13% additional variance, over and above that explained by the first component. The items within the second principal component conceptually clustered into two areas. The first was hearing aid management, which included inserting earmolds, promoting hearing aid checks, using Ling sounds, troubleshooting hearing aids, and using FM. Developing sign language also loaded onto this subcomponent, but with a loading value of .15, in contrast to the other skills with loading values ranging from .27 to .37. The second area was composed of items such as promoting language in routines and developing oral language, and carryover of speech and language, all of which are skills related to supporting families in providing an enriched language environment for their children.

Discussion

Service Setting and Family Involvement

The goal of research questions 1a and 1b was to describe where children who are hard of hearing and their families receive EI services and describe the relationship between setting and family participation in services. Most of the children in this cohort received at least some services in their homes; however, the percent of families reporting home-based services declined from the infant to the preschool age groups. Approximately 60% of the oldest/preschool age group reported receiving home-based services. The effect of setting on family participation was striking. When home was the setting for EI services, 95% of the families reported they always or most of the time participated. When services were delivered in nonhome locations, including day care, center-based, or a therapist's office or clinic, 16 of 56 (28.6%) of families reported their participation as always or most of the time.

Krauss (1990) described the establishment of EI services as redefining the service recipient as the family rather than the child alone. McGonigel and Garland (1988) noted that the goal for family involvement transitioned from passive review and approval of the professionals' goals and practices to inclusion of parents in carrying out professionally directed interventions. Provision of services in the home facilitates the role of professionals in coaching and supporting parents to use their own resources and skills to promote their child's development in the context of daily routines and activities. Research has demonstrated that delivery models that facilitate inclusion of the family are essential to improved child language outcomes (Moeller, 2000; Spencer, 2004; Watkin et al., 2007). The decreased rate of family participation in nonhome locations does not appear to be consistent with best practice goals of involving families in EI.

Among the OCHL families, those with children who received services in day care reported being the least likely to participate. Within this group, 75% of the mothers did not have a college degree. This raises an empirical question to be explored in the future: Do families from less advantaged homes experience barriers to home-based service access?

In addition to being less likely to participate in services, OCHL families with lower levels of maternal education were also at risk of later diagnostic follow-up after referral from hearing screening, resulting in later hearing aid fitting, than were children from more advantaged homes (Holte et al., 2012). In addition, the rate of hearing aid use among children whose mothers had less education was lower compared with those whose mothers had higher levels of education (Walker et al., 2013).

Ensuring regular hearing aid use appears to be more of a challenge for less-resourced families when EI services are delivered outside of the home. Periods of inconsistent auditory access due to factors such as late fitting and low hearing aid use result in children receiving inconsistent access to linguistic input. Over time, periods of inconsistent access may have a cumulative effect of reducing linguistic experience and overall language exposure (see Moeller & Tomblin, 2015). Working with an EI professional who has the skills and knowledge to support a family as they learn to manage and establish consistent device use may enhance the likelihood of increasing auditory access. The findings of the current study collectively suggest the need to continue to find ways to involve and support less-resourced families, including flexible scheduling that would allow for provision of home visits.

In order to reap the benefits of family involvement, innovative service delivery models must be explored. For example, it should be possible for many families to employ technological advances that are currently available. Adults in their twenties and thirties, the age range of most parents of young children, are more likely than any other age group to own a smartphone, regardless of income level (Pew Research Center, 2013). Fifty-six percent of American adults own smartphones that support text messaging and free or inexpensive video conferencing applications. The use of this technology within EI services has yet to be widely explored, although these options broaden the possibilities for EI professional and parent interaction for both scheduling and intervention practices. Regardless of the strategy used to increase family involvement, a thorough understanding of the resources, preferences, and constraints that operate within a family's structure is necessary to develop an appropriate model with each family. Unless services match the resources, needs, and expectations of a family, they are likely to remain underutilized.

Effect of Preparation, Caseload Composition, and Experience on Comfort Scores

Research questions 2a and 2b sought to describe factors regarding preparation, caseload composition, and experience, and their relationship to provider comfort with specific EI skills. The majority of EI professionals (88%) providing services to children and families in the OCHL study had a graduate degree in SLP or TODHH, areas that have been identified as key disciplines for serving these children and their families. Thus, the families whose service providers completed surveys had access to professionals with considerable preparation.

When professionals were ranked on the relevance of their self-reported preparation in regard to working with CDHH, three categories of preparation emerged. Professionals in the lowest level had a bachelor's degree or a master's degree with no additional certification. Those in the medium group typically had a master's degree as an SLP or a teacher of CDHH, with some continuing education related to childhood hearing loss and more than one certification. Members of the most highly prepared group had at least one master's degree, usually at a program emphasizing childhood hearing loss. All had additional certifications and relevant continuing education. These same professionals were also asked to indicate their comfort with providing 18 specific EI skills. Although some variation was seen, overall comfort scores clustered around a score of 3, regardless of level of preparation. This restricted variation in most of the ratings may have been a function of the limited response range (1 to 4) available or the overall high level of preparation among this cohort. Within this group of well-educated EI professionals, some differences in comfort with skills that are fundamental to optimizing speech and language outcomes did emerge. However, it is important to recognize that a majority of the correlations between provider preparation and comfort levels are weak to modest. This suggests that additional factors not revealed in this analysis may be playing a role, and/or that there is a need for continued refinement of measures of provider characteristics and behaviors, including objective measures that extend beyond self-report. Eisenberg et al. (2007) noted that the types of measures needed to assess quality of services are lacking, so measurement is challenging.

Among the skills, developing sign language skills was a notable exception with regard to provider comfort. The low comfort scores that were consistently associated with sign language may have resulted from several factors. Although 54.2% of the professionals were TODHH, and thus might be expected to be comfortable signing, 42.8% had degrees in SLP, early childhood education, or early childhood special education. Sign language is not typically part of the curriculum in any of these areas. Furthermore, several programs providing services to the children in this study emphasize oral language, which may have attracted TODHH with minimal fluency in sign language and would provide fewer opportunities to consistently use sign, potentially affecting skill level and comfort. For children whose families choose a sign language approach or who require that expertise for whatever reason, lack of professional comfort with signing would be a concern for families.

Other factors that might influence providers' comfort with specific skills—including the percent of CDHH on a professional's caseload and years of experience—were also analyzed. Caseload composition, as defined by the percent of CDHH on a caseload, was significantly related to every skill except developing sign language. The strongest relationships with caseload were found for skills related to hearing aid use and management and promoting listening skills. More than half of the EI professionals represented here had caseloads that were composed entirely of CDHH. These professionals were likely to have been employed by programs specifically designed to serve CDHH, and, as such, were provided opportunities for hands-on practice with hearing technologies and promoting speech and language for CDHH. Another possible explanation for this relationship between caseload composition and comfort is that, regardless of employment site, EI professionals with a higher level of comfort working with CDHH were more likely to have them assigned to their caseloads. Even when professionals are not associated with a program specifically developed to serve them, having multiple children with hearing loss may provide motivation to become proficient in a relevant skillset. Further research is needed to understand effects of program characteristics, specialization, and specific experience with CDHH on professionals' knowledge and skills.

The number of years of EI experience was weakly correlated to provider confidence in language development skills including assessing language, vocabulary development, promoting language in daily routines, assessing communication approach, and building language through play. Skills such as these are fundamental and essential in supporting language development in young children with a variety of developmental challenges.

This study included a subanalysis using PCA to verify that the 18-item survey included a related set of items. Although not a central research question, that analysis revealed an interesting finding that all but one item loaded equivalently on a first component, which explained 59% of the variance in provider comfort scores. This finding suggests that the survey measured a coherent set of skills that appear to be relevant to the provision of EI services. A second component (subset) of skills identified by the PCA contributed to explaining a modest additional amount of variance (13%) in provider comfort. Although contributing only modest additional variance, most of the skills in this component supported development of spoken language in CDHH (DesJardin & Eisenberg, 2007).

Limitations

Several limitations to the current study should be acknowledged. Because of the way the questions were worded, it was not possible to determine with confidence the proportion of services received in each location when parents reported receiving both home-based and outside of the home services. Thus, a family might have received 90% of the services outside of the home and 10% at home or vice versa; however, this could not be ascertained. In regard to the comfort ratings, we designed a 4-point scale, rather than providing a wider range of options with little semantic difference between adjacent ratings of comfort. As a result, ecological and statistical validity were maintained; however, the overall variability may have been reduced.

Reliance on provider report introduces a complication in interpreting the data, because people are subjective in rating their own competence levels. As part of a broader project undertaken to explore early childhood education teachers' confidence and competence across a wide range of subjects, Garbett (2003) provided evidence that knowledge of science among student teachers in early childhood education was poor. Only 15% of them were judged to have an adequate knowledge in basic science concepts to provide science education to young children. Despite these low levels, the students reported a high level of confidence, indicating they were unaware of how much they didn't know and how this might affect their ability to provide appropriate experiences for their preschool students. The process of self-assessment is clearly complex, and by its very nature can never be entirely objective or free from the beliefs and values individuals hold.

One of the strengths of this study is ironically also a limitation. Because the study population was limited to children with no other developmental challenges and who were in a family in which at least one parent was a fluent English speaker, they are not representative of the heterogeneous population of CDHH. In addition, the longitudinal design of the study attracted a cohort of families who had the resources to spend at least half a day annually in testing, with many families spending time and resources to travel to an appointment site. Although families were reimbursed for travel expenses and their time, this may not have been sufficient to offset the costs for families with fewer resources, making it less likely for them to participate.

Another potential limitation is the sample of EI professionals. Some of the centers participating in the OCHL study are associated with programs known for their expertise in childhood hearing loss. These centers are likely to have attracted EI professionals with higher levels of education and specialization and may not accurately represent the larger population of EI providers. And finally, many of the children and their families were recruited through outreach to EI professionals. Thus, children who did not qualify for EI services or whose families declined services were likely underrepresented in the OCHL sample. Thus, the findings reported here most likely represent a best-case scenario.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that families are less likely to be involved in EI when it is delivered outside of their home. The benefit of family involvement in EI in regard to child language outcomes has been established. Thus, when traditional home-based services are not feasible, professionals should explore providing access through creative solutions with technologies or consider other accommodations to promote development of a relationship between themselves and the family. However, in order to capitalize on family involvement in regard to language outcomes for children who are hard of hearing, EI professionals need to be both competent and confident in the skills necessary to support those outcomes.

Caseload composition, specifically the percent of CDHH, was significantly associated with EI professionals' comfort scores. Our results suggest that access to hands-on experience working with CDHH, potentially from specialized preparation or a high percentage of CDHH on a current caseload, contributes to professional comfort. Future research should explore what factors underlie the relationship between professionals' confidence and caseload composition, and what role professional preparation and/or specialization plays.

Even within this well-prepared group of EI professionals, some differences in comfort scores were reported, especially by those with the least specialized preparation. Although the relationship between caseload composition and specialized preparation requires further investigation, engendering EI professionals' self-efficacy in areas that support access to audition may increase the likelihood that they will be more effective in empowering parents to manage these tasks. Parents in turn, may be better prepared in their journey toward supporting optimal speech and language outcomes for their children. As noted by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders 2006 panel, the relationships among the many variables involved in EI are complex. The information presented here is an initial effort in understanding how those multiple variables contribute to outcomes of CDHH and their families.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant NIH/NIDCD 5 R01 DC009560-03 (awarded to J. Bruce Tomblin and Mary Pat Moeller). The authors acknowledge the support of Sophie Ambrose, who provided input on previous versions of this manuscript. Special thanks go to Marlea O'Brien for coordinating the Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss project, as well as to the examiners at the University of Iowa, Boys Town National Research Hospital, and University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill. Special thanks also go to the families and children who participated in the research.

The content of this project is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant NIH/NIDCD 5 R01 DC009560-03 (awarded to J. Bruce Tomblin and Mary Pat Moeller).

Footnote

We note here that statistical analyses were performed both using the continuous specialization score (1 to 17) and the ordinal grouped variable (low, medium, high) with no appreciable difference in the results, which indicates robustness in the derived specialization score. In every case, the p-value decreased using the continuous measure; thus, the grouped analysis provided a more conservative estimate of the relationship between specialization score and comfort.

References

- Ambrose S. E., Walker E. A., Unflat-Berry L., Oleson J. J., & Moeller M. P. (2015). Quantity and quality of caregivers' linguistic input to 18-month and 3-year-old children who are hard of hearing. Ear and Hearing, 36, 48S–59S. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (2007). Year 2007 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics, 120(4), 898–921. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2008). Service provision to children who are deaf and hard of hearing, birth to 36 months [Technical report]. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/policy/TR2008-00301/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). 2012 Annual data: Early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) program. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/ehdi-data2012.html

- Chandler L. K., Cochran D. C., Christensen K. A., Dinnebeil L. A., Gallagher P. A., Lifter L., … Spino M. (2012). The alignment of CEC/DEC and NAEYC personnel preparation standards. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 32(1), 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cone-Wesson B., Vohr B. R., Sininger Y. S., Widen J. E., Folsom R. C., Gorga M. P., & Norton S. J. (2000). Identification of neonatal hearing impairment: Infants with hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 21(5), 488–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council for Clinical Certification in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2014). 2014 standards for the Certificate of Clinical Competence in Speech-Language Pathology. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/Certification/2014-Speech-Language-Pathology-Certification-Standards

- Council for Exceptional Children. (2004). The Council for Exceptional Children definition of a well-prepared special education teacher. Arlington, VA: CEC Board of Directors. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond L., Wei R. C., Andree A., Richardson N., & Orphanos S. (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession. Washington, DC: National Staff Development Council. [Google Scholar]

- DesJardin J. L., & Eisenberg L. S. (2007). Maternal contributions: Supporting language development in young children with cochlear implants. Ear and Hearing, 28(4), 456–469. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31806dc1ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg L. S., Widen J. E., Yoshinaga-Itano C., Norton S., Thal D., Niparko J. K., & Vohr B. (2007). Current state of knowledge: Implications for developmental research-key issues. Ear and Hearing, 28(6), 773–777. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e318157f06c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrand P., McMullen M., Jowett R., & Humphreys A. (2006). Implementing competency recommendations into pre-registration nursing curricula: Effects upon levels of confidence in clinical skills. Nurse Education Today, 26, 97–103. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiburger O. A. (2002). Increasing student self-confidence and competency. Nurse Educator, 27(2), 58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbett D. (2003). Science education in early childhood teacher education: Putting forward a case to enhance student teachers' confidence and competence. Research in Science Education, 33, 467–481. doi:10.1023/B:RISE.0000005251.20085.62 [Google Scholar]

- Green D. R., Gaffney M., Devine O., & Gross S. (2007). Determining the effect of newborn hearing screening legislation: An analysis of state hearing screening rates. Public Health Report, 122(2), 198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpin K. S., Smith K. Y., Widen J. E., & Chertoff M. E. (2010). Effects of universal newborn hearing screening on an early intervention program for children with hearing loss, birth to 3 years of age. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 21(3), 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell P. L., Kearl G. W., Reed E. L., Grigsby D. G., & Caudill T. S. (1993). Medical students' confidence and the characteristics of their clinical experiences in a primary care clerkship. Academic Medicine, 68(7), 577–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M., & Roush J. (1996). Age of suspicion, identification, and intervention for infants and young children with hearing loss: A national study. Ear and Hearing, 17(1), 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M., Roush J., & Wallace J. (2003). Trends in age of identification and intervention in infants with hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 24(1), 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden G., Rosenberg G., Barker K., Tuhrim S., & Brenner B. (1993). The recruitment of research participants: A review. Social Work in Health Care, 19(2), 1–44. doi:10.1300/J010v19n02_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holte L., Walker E., Oleson J., Spratford M., Moeller M. P., Roush P., … Tomblin J. B. (2012). Factors influencing follow-up to newborn hearing screening for infants who are hard of hearing. American Journal of Audiology, 21(2), 163–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston K. T., & Perigoe C. B. (2010). Speech-language pathologists: Vital listening and spoken language professionals. The Volta Review, 110(2), 210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C., McCann D., Campbell M. J., Kimm L., & Thornton R. (2005). Universal newborn screening for permanent childhood hearing impairment: An 8-year follow-up of a controlled trial. Lancet, 366(9486), 660–662. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67138-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss M. W. (1990). New precedent in family policy: Individualized family service plan. Exceptional Children, 56(5), 388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marge D. K., & Marge M. (2005). Beyond newborn hearing screening: Meeting the educational and health care needs of in infants and young children with hearing loss in America. Report of the National Consensus Conference on Effective Educational and Health Care Interventions for Infants and Young Children with Hearing Loss. September 10–12, 2004. Syracuse, NY: Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, SUNY Upstate Medical University. [Google Scholar]

- McCreery R. W., Bentler R. A., & Roush P. A. (2013). Characteristics of hearing aid fittings in infants and young children. Ear and Hearing, 34(6), 701–710. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828f1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery R. W., Walker E. A., Spratford M., Bentler R., Holte L., Roush P. A., … Moeller M. P. (2015). Longitudinal predictors of aided speech audibility in infants and children. Ear and Hearing, 36, 60S–75S. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigel M. J., & Garland C. W. (1988). The individualized family service plan and the early intervention team: Team and family issues and recommended practices. Infants and Young Children, 1(1), 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Meadow-Orlans K., Mertens D., & Sass-Lehrer M. (2003). Parents and their deaf children: The early years. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller M. P. (2000). Early intervention and language development in children who are deaf and hard of hearing. Pediatrics, 106(3). doi:10.1542/peds.106.3.e43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller M. P., Carr G., Seaver L., Stredler-Brown A., & Holzinger D. (2013). Best practices in family-centered early intervention for children who are deaf or hard of hearing: An international consensus statement. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 18(4), 429–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller M. P., & Tomblin J. B. (2015). An introduction to the Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss study. Ear and Hearing, 36, 4S–13S. doi:10.1097/AUD0000000000000210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton C. C., & Nance W. E. (2006). Newborn hearing screening—A silent revolution. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(20), 2151–2164. doi:10.1056/NEJMra050700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz K., & Blaiser K. (2011). Audiologists and speech-language pathologists: Making critical cross-disciplinary connections for quality early hearing detection and intervention. Perspectives on Audiology, 7, 34–42. doi:10.1044/poa7.1.34 [Google Scholar]

- Muse C., Harrison J., Yoshinaga-Itano C., Grimes A., Brookhouser P. E., Epstein S., … Martin B. (2013). Supplement to the JCIH 2007 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early intervention after confirmation that a child is deaf or hard of hearing. Pediatrics, 131(4), e1324–e1349. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2009). NAEYC standards for early childhood professional preparation [Position statement]. Washington, DC: NAEYC Standards Workgroups 2008–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2013). Smartphone ownership—2013 update. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Smartphone-Ownership-2013.aspx