Abstract

This is a correspondence about “Beclin‐1 is required for chromosome congression and proper outer kinetochore assembly”.

Subject Categories: Cell Cycle

Monoallelic loss of the key autophagy gene Beclin 1 promotes tumorigenesis in mice 1. One possible underlying mechanism is provided by the observation that Beclin 1 heterozygosity concomitantly facilitates numerical and structural chromosomal aberrations culminating in chromosomal instability (CIN). This feature is becoming particularly evident in cells in which apoptosis has been prevented 2. Whether CIN arising upon reduction of Beclin 1 levels reflects a consequence of metabolic imbalance due to defective autophagy or an autophagy‐independent function of Beclin 1 in genome maintenance remained unexplored until recently. To this end, Frémont, Gérard and colleagues 3 provided evidence that Beclin 1 functions in mitotic kinetochore assembly independently of other established autophagy regulators. In contrast to RNAi‐mediated depletion of Vps34, Vps15, Atg5 and other essential autophagy genes, Beclin 1 depletion caused (i) an increase in mitotic index, (ii) prometaphase delay associated with aberrant chromosome congression and segregation as well as (iii) selective delocalization of critical kinetochore components, such as CENP‐F, resulting in CIN.

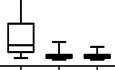

We recently undertook a functional genomics approach to assess the involvement of proteins containing a “BCL2 homology 3” (BH3) domain in normal mitotic division and under conditions of microtubule poisoning 4. BH3 domains are structural motives ubiquitous in, yet not exclusive for, the BCL2 family of proteins, and the presence of such a domain in Beclin 1 led to its discovery in a yeast two‐hybrid screen as a putative BCL2 binding partner 5, 6, 7, 8. We therefore also depleted Beclin 1, next to other BH3‐domain‐containing proteins 4, with two validated siRNAs, and observed no measurable mitotic phenotype upon live cell imaging of cells traversing mitosis. As our observations were at odds with the recently published data by Frémont, Gérard and colleagues, we designed a set of experiments aiming to rule out (i) that our assays are not sufficiently sensitive to reveal a potential mitotic function of Beclin 1 or (ii) that our siRNA depletion was insufficient to recapitulate the reported phenotypes. However, the “Beclin 1‐I” and “Beclin 1‐II” siRNAs used in our analyses effectively depleted their target at the protein level and Beclin 1‐II appeared reproducibly more potent than the siRNA sequence utilized by Frémont, Gérard and colleagues (hereafter referred to as “Beclin 1‐ER,” for EMBO Reports, Fig 1A). Interestingly, whereas Beclin 1‐ER siRNA readily triggered the severe mitotic phenotypes described, such as accumulation of cells with a G2/M DNA content (Fig 1B), prometaphase delay accompanied by chromosome congression and segregation defects (Fig 1C and D) and loss of CENP‐F localization to kinetochores (Fig 1E), neither Beclin 1‐I nor Beclin 1‐II siRNA caused such effects (Fig 1A–E).

Figure 1. Beclin 1 is dispensable for chromosome congression and proper outer kinetochore assembly.

(A) HeLaS3 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs for either 48 or 72 h and subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (B) Nicoletti staining of cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs for 72 h. (C, D) HeLaS3‐H2B‐GFP cells were subjected to time‐lapse video microscopy following transfection with the indicated siRNAs for 48 h. (C) Box (interquartile range) and whisker (min to max) plots showing the elapsed time (min) between NEBD and anaphase for 50 individual cells. Depicted are the data of one representative experiment (n = 3). (D) Movie stills from four representative cells quantified in (C). Scale bar = 10 μM. (E) HeLaS3 cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs for a total of 48 h were subjected to immunofluorescence with the indicated antibodies. The DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bar = 10 μM. (F, G) HeLaS3‐H2B‐GFP cells were subjected to siRNA transfection with a constant amount of RNA duplex composed by either the indicated sequence or a mixture of decreasing Becn1‐ER (50, 25 and 12.5%) and increasing amount of Gl2 siRNA (50, 75 and 88.5%, from left to right). (F) A fraction of the cells treated as indicated was subjected to immunoblot with the indicated antibodies, whereas the remaining cells were subjected to live cell imaging. (G) Box (interquartile range) and whisker (min to max) plots showing the elapsed time (min) between NEBD and anaphase for 50 individual cells (n = 1). (H) Heatmap representing the expression of each probe set significantly differentially expressed at a 1% false discovery rate against its mean expression across all samples analysed by transcriptome profiling (Fig EV1A and Table EV2).

To test the extent of correlation between Beclin 1 protein depletion and the penetrance of the mitotic phenotype, we transfected cells with a constant amount of siRNA targeting luciferase (Gl2), Beclin 1‐I, Beclin 1‐II, Beclin 1‐ER or a mixture of graded amounts of Beclin 1‐ER and Gl2 siRNA. Part of each transfected sample was subjected to protein extraction and immunoblot analysis, whereas the remaining cells were subjected to live cell imaging (Fig 1F and G, respectively). Although Beclin 1‐II showed the largest extent of protein depletion, no measurable phenotype could be seen (Fig 1F and G). In stark contrast and despite less effective protein depletion, transfection of Beclin 1‐ER siRNA triggered an increase in the time elapsed between nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD) and anaphase. This phenotype could be readily decreased in severity upon reduction of the amount of Beclin 1‐ER siRNA transfected, although no significant change of the degree of Beclin 1 depletion was noted under these conditions (Fig 1F and G). Taken together, our data show that the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA leads to a mitotic phenotype that is not caused by Beclin 1 protein depletion.

Although the possibility of an off‐target effect caused by Beclin 1‐ER siRNA seemed to be excluded by the fact that ectopic expression of HA‐Beclin 1, insensitive to RNAi‐mediated degradation, could rescue the mitotic phenotype, a closer inspection of Fig 1A in Frémont, Gérard and colleagues reveals that the interpretation of the data is questionable. The authors used flow cytometry to compare two distinct cell lines that show a drastic difference in their cell cycle distribution with the cell line overexpressing HA‐Beclin 1 displaying a reduced fraction of cells in G2/M, when compared to the parental cell line. Upon Beclin 1 knockdown, however, both cell lines show a more than twofold increase in G2/M cells when compared to controls. This documents that the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA triggers the same relative increase in G2/M cells in both cell lines investigated and that this effect is not prevented by the expression of RNAi‐resistant HA‐Beclin 1. We therefore conclude that the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA triggers the knockdown of one or more factors critical for outer kinetochore assembly by an off‐target effect. These factors, however, are unrelated to Beclin 1.

Given that the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA transfection triggered a selective delocalization of kinetochore proteins downstream of the KMN network 9 and given that such phenomenon can be clearly causative of all other phenotypes attributed to Beclin 1 by Frémont, Gérard and colleagues, we reasoned that a downregulation of a limited number, if not that of a single, factor could be responsible for the reported phenotypes. Thus, we decided to use transcriptome profiling to define changes induced by Beclin 1‐ER siRNA transfection. To this end, Beclin 1‐ER siRNA might trigger changes at the transcriptome scale not only by impinging on Beclin 1 expression and several potential off‐targets, but also secondary to (i) the differential cell cycle distribution that this siRNA transfection induces and (ii) the impaired autophagic flux triggered by Beclin 1 knockdown. To minimize the impact of secondary effects by Beclin 1‐ER siRNA on our analysis, we operated our comparison (i) between cells synchronized in mitosis and (ii) transfected with Beclin 1‐ER or Beclin 1‐II siRNA, instead of a non‐targeting control.

After verification of Beclin 1 knockdown and effective synchronization across three biological replicates (Fig EV1A), we obtained total RNA and hybridized it on Affymetrix HGU133 Plus 2.0 Gene Chips. To our surprise, 1,095 probe sets were more than twofold downregulated by the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA (compared to the Beclin 1‐II siRNA) at a 1% false discovery rate. These transcripts could be assigned to 716 genes (Table EV1). The Beclin 1‐II siRNA downregulated 610 genes, measured in total by 935 probe sets (Table EV1). Our data set highlights that off‐target effects of both siRNAs were pervasive (Fig 1H) and confirms previous findings highlighting the technical challenges associated with high‐copy siRNA transfection 10.

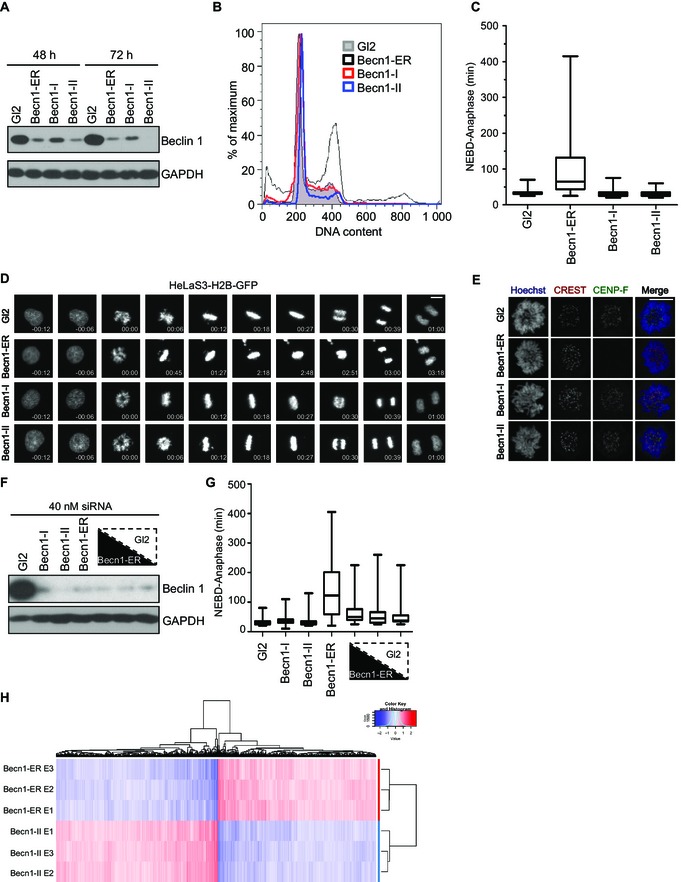

Figure EV1. Search for possible off‐target effects of the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA.

(A) HeLaS3 cells have been either left asynchronous (M Sync −) or synchronized in mitosis by a single thymidine arrest, released in the presence of nocodazole, followed by mitotic shake‐off (M Sync +). SiRNA with the indicated sequences was performed for a total of 48 h. Part of the cells obtained in three independent experiments was subjected to protein extraction and immunoblot with the indicated antibodies, whereas the remaining cells were subjected to RNA extraction followed by hybridization on the gene chips indicated. The results of the transcriptome profiling are depicted in Fig 1H and Table EV1. (B) HeLaS3‐H2B‐GFP cells were subjected to siRNA transfection with a constant amount of RNA duplex composed by either the indicated sequence or a mixture of decreasing Becn1‐ER (50, 25 and 12.5%) and increasing amount of Gl2 siRNA (50, 75 and 88.5%, from left to right). Please note that the lowest panel (GAPDH, representing a loading control) has been duplicated from Fig 1F (which has been generated using the same samples). The NUP88 immunoblot is shown in addition. (C) HeLaS3‐H2B‐GFP cells were subjected to time‐lapse video microscopy following transfection with the indicated siRNAs for 48 h. Box (interquartile range) and whisker (min to max) plots showing the elapsed time (min) between NEBD and anaphase for 50 individual cells (n = 1).

Of note, Beclin 1 mRNA was found significantly downregulated upon Beclin 1‐II siRNA by two out of three Affymetrix probes directed to Beclin 1, confirming that Beclin 1‐II siRNA leads to a more potent depletion of the Beclin 1 transcript when compared to Beclin 1‐ER (Table EV1). Concerning possible factors being responsible for the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA phenotype, NUP88, a protein whose transcript shows a large overlap with the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA and that interacts with RanBP2 (which in turn causes the same kinetochore defects upon siRNA‐mediated depletion 11), was neither downregulated at the transcript level (Table EV1), nor at the protein level (Fig EV1B) upon Beclin 1‐ER siRNA transfection. Finally we focused on Nek1, a gene that (i) showed homology with the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA, (ii) appeared downregulated upon Beclin 1‐ER transfection and (iii) was previously implicated in faithful chromosome segregation 12. Nek1 did not show, upon direct siRNA‐mediated downregulation, an extension in the mitotic duration, suggesting that the noted Nek1 reduction is not responsible for the kinetochore assembly defects assigned to Beclin 1 (Fig EV1C).

SiRNA off‐target effects are often caused by miRNA‐like seed interactions that do not require an overall identity across the entire siRNA sequence 13. We therefore aimed to identify likely candidates by RNAplex 14, which is better suited to identify short highly stable interactions. Among the 200 transcripts displaying the largest binding energy to either the guide strand or the passenger strand (the top 100 for each), 22 were significantly downregulated upon siRNA transfection (Table EV2). To the best of our knowledge, none of them (with the exception of Beclin 1 itself) has been previously reported to function at the kinetochore.

Taken together, we show here that Beclin 1 is not required for kinetochore assembly. Unfortunately, we could not pinpoint the factor(s) downregulated by the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA that is responsible for the kinetochore phenotype described by Frémont, Gérard and colleagues. Clearly, it remains possible that our siRNA off‐target identification strategy is invalidated by the eventuality of complex off‐target effects involving multiple factors, regulated to a small extent 15. While rescuing an siRNA‐mediated phenotype remains technically challenging, the CRISPR‐Cas9 technology has become available and can serve as complementary tool to dissect the function of critical genes in cell culture systems 16. Retrospectively, the employment of multiple siRNA sequences against the same target across various phenotypic readouts as performed here would have probably been sufficient to recognize the spuriousness of the Beclin 1‐ER siRNA phenotype.

Author contributions

LLF performed the experiments, designed the research, analysed the data, wrote the paper and conceived the study. JR performed the bioinformatic analysis. MDH performed the experiments and analysed the data. SG provided reagents and analysed the data. AV analysed the data, wrote the paper and supervised the work. All authors edited the manuscript.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figure PDF

Table EV1

Table EV2

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Erich Nigg for sharing reagents, to Claudia Soratroi, Anita Kofler and Barbara Gschirr for technical assistance, to Martin Offterdinger and Reinhard Sigl for support in microscopy and to Reinhard Kofler for help with the transcriptome analysis. Our research is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; I1298), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR‐2036), the Tyrolean Science Fund (TWF) and the “Krebshilfe Tirol.” L.L.F. was supported in part by the EMBO‐LTF Programme.

Comment on: S Frémont et al (April 2013)

References

- 1. Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G et al (2003) Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene J Clin Invest 112: 1809–1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mathew R, Kongara S, Beaudoin B et al (2007) Autophagy suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability Genes Dev 21: 1367–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fremont S, Gerard A, Galloux M et al (2013) Beclin‐1 is required for chromosome congression and proper outer kinetochore assembly EMBO Rep 14: 364–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haschka MD, Soratroi C, Kirschnek S et al (2015) The NOXA‐MCL1‐BIM axis defines lifespan on extended mitotic arrest Nat Commun 6: 6891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feng W, Huang S, Wu H et al (2007) Molecular basis of Bcl‐xL's target recognition versatility revealed by the structure of Bcl‐xL in complex with the BH3 domain of Beclin‐1 J Mol Biol 372: 223–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liang XH, Kleeman LK, Jiang HH et al (1998) Protection against fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis by beclin, a novel Bcl‐2‐interacting protein J Virol 72: 8586–8596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maiuri MC, Le Toumelin G, Criollo A et al (2007) Functional and physical interaction between Bcl‐X(L) and a BH3‐like domain in Beclin‐1 EMBO J 26: 2527–2539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oberstein A, Jeffrey PD, Shi Y (2007) Crystal structure of the Bcl‐XL‐Beclin 1 peptide complex: Beclin 1 is a novel BH3‐only protein J Biol Chem 282: 13123–13132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Santaguida S, Musacchio A (2009) The life and miracles of kinetochores EMBO J 28: 2511–2531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jackson AL, Bartz SR, Schelter J et al (2003) Expression profiling reveals off‐target gene regulation by RNAi Nat Biotechnol 21: 635–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joseph J, Liu ST, Jablonski SA et al (2004) The RanGAP1‐RanBP2 complex is essential for microtubule‐kinetochore interactions in vivo Curr Biol 14: 611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen Y, Chen CF, Chiang HC et al (2011) Mutation of NIMA‐related kinase 1 (NEK1) leads to chromosome instability Mol Cancer 10: 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Birmingham A, Anderson EM, Reynolds A et al (2006) 3′UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off‐targets Nat Methods 3: 199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tafer H, Hofacker IL (2008) RNAplex: a fast tool for RNA‐RNA interaction search Bioinformatics 24: 2657–2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jackson AL, Linsley PS (2010) Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off‐target effects for target identification and therapeutic application Nat Rev Drug Discov 9: 57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F (2014) Development and applications of CRISPR‐Cas9 for genome engineering Cell 157: 1262–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix

Expanded View Figure PDF

Table EV1

Table EV2