Abstract

Background

Chronic constipation (CC) is common in the community but surprisingly little is known about relevant gastro-intestinal (GI) and non-GI co-morbidities.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to assess the epidemiology of CC and in particular provide new insights into the co-morbidities linked to this condition.

Methods

In a prospective, population-based nested case-control study, a cohort of randomly selected community residents (n = 8006) were mailed a validated self-report gastrointestinal symptom questionnaire. CC was defined according to Rome III criteria. Medical records of each case and control were abstracted to identify potential CC comorbidities.

Results

Altogether 3831 (48%) subjects returned questionnaires; 307 met criteria for CC. Age-adjusted prevalence in females was 8.7 (95% confidence interval (CI) 7.1–10.3) and 5.1 (3.6–6.7) in males, per 100 persons. CC was not associated with most GI pathology, but the odds for constipation were increased in subjects with anal surgery relative to those without (odds ratio (OR) = 3.3, 95% CI 1.2–9.1). In those with constipation vs those without, neurological diseases including Parkinson’s disease (OR = 6.5, 95% CI 2.9–14.4) and multiple sclerosis (OR = 5.5, 95% CI 1.9–15.8) showed significantly increased odds for chronic constipation, adjusting for age and gender. In addition, modestly increased odds for chronic constipation in those with angina (OR = 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.9) and myocardial infarction (OR = 1.5, 95% CI 1.0–2.4) were observed.

Conclusions

Neurological and cardiovascular diseases are linked to constipation but in the community constipation is unlikely to account for most lower GI pathology.

Keywords: Chronic constipation, community studies, co-morbidities

Introduction

Chronic constipation is a common gastrointestinal disorder that is associated with impaired quality of life and increased use of health resources.1–4 Population-based studies have estimated that approximately 10–20% of otherwise healthy people report one or more symptoms of chronic constipation, although the prevalence varies depending on the definition applied and study setting.5,6

Constipation has daily implications for those affected, and although only one-third of affected persons seek care, it is associated with enormous socioeconomic costs due to investigations and use of medications.2,5 A minority of those with constipation seek medical care, but this still accounts for an estimated 5.7 million ambulatory visits.7

In the clinic, physicians usually focus on the infrequency of bowel movements, straining, hard stools and feelings of incomplete evacuation when documenting the problem; patients, however, often have a broader set of complaints or comorbidities they believe may be linked to the condition.8–11 More importantly, we and others have observed that constipation appears to be associated with the development of neurodegenerative disease, specifically Parkinson disease.12–15 Moreover, constipation may be a major predisposing factor for diverticulitis16 and local anal pathology,17–19 although this remains controversial.20,21

A comorbidity is defined as a condition that coexists with an index disease. This includes risk factors for and complications of the disease of interest, which here is chronic constipation. The comorbid occurrence of constipation with a second disease in identical patients suggests that the two diseases share a set of common risk factors or a set of common pathophysiological pathways. Thus, we aimed to assess the epidemiology of chronic constipation and in particular provide new insights into common co-morbidities believed to be linked to this condition.

Materials and methods

This study is a population-based, nested case-control study with subjects selected from an age- and gender-stratified community random sample sent a gastro-intestinal (GI) symptom survey in 2008–2009 which included constipation-related questions. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center.

Subjects

The study milieu has been described in prior publications but in brief22–24 the Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA population comprises approximately 120,000 people of whom 89% are white; sociodemographically, this community strongly resembles the US white population. Mayo Clinic is the major provider of medical care.23 During any given four-year period, over 95% of local residents will have had at least one local health care contact.23 Pertinent clinical data are accessible because the Mayo Clinic has maintained, since 1910, extensive indices based on clinical and histological diagnoses and surgical procedures.22 The system was further developed by the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which created similar indices for the records of the other providers of medical care to Olmsted County residents. The Rochester Epidemiology Project records linkage system, therefore, provides what is essentially an enumeration of the population from which samples can be drawn.23 These data resources have been utilized in a series of investigations into the epidemiology of functional GI disorders.25–29 We used this system to draw a series of random samples of Olmsted County residents stratified by age (five-year intervals between 20–94 years) and sex (equal numbers of men and women).

Survey methods

For the current study, a previously assembled cohort (n = 4451)25–29 and a new age- and gender-stratified random sample (n = 3555)30 of Olmsted County residents (total = 8006) were mailed validated self-report gastrointestinal symptom questionnaires (Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire (BDQ)) in 2008 and 2009. The original BDQ27 was designed to measure GI symptoms experienced over the previous year and to elicit a brief prior medical history with respect to somatic symptoms. The questionnaire has been modified over time. The original BDQ and modified versions have been shown to be reliable and valid measures of GI symptoms in previous studies,31–33 and the current version of the BDQ has also been shown to be a reliable and valid measurement of bowel symptoms.30 The current BDQ incorporated 27 gastrointestinal symptoms including constipation-related questions.

Priming letters were initially mailed to highlight that a GI questionnaire would be sent. Later, an explanatory letter accompanied the survey which was mailed to a total of 8006 Olmsted County residents. Reminder letters were mailed at weeks 3 to 6 after the initial mailing to non-responders. Subjects who indicated at any point that they did not wish to complete the survey were not contacted further. Otherwise, non-responders were contacted by telephone at week 9 to request their participation and verify their residence within the County.

Definitions

Based upon the survey responses, Olmsted County residents were classified as having constipation using two definitions. Of note, the survey questions were specific on the issue of laxatives. Patients were asked to report their bowel pattern in the absence of laxative use.

Sensitive (broad) criteria for chronic constipation

Two or more of the following: (a) fewer than three bowel movements per week, (b) straining during at least 25% of defecations, (c) lumpy or hard stools on at least 25% of defecations, and (d) sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25% of defecations. The survey asked respondents to consider the past year.

Specific criteria for chronic constipation (by Rome III criteria)34

All three criteria below had to be met (over the past year):

- Two or more of the following:

- Straining during at least 25% of defecations.

- Lumpy or hard stools in at least 25% of defecations.

- Sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25% of defecations.

- Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage for at least 25% of defecations.

- Manual maneuvers to facilitate at least 25% of defecations.

- Fewer than three defecations per week.

Loose stools rarely present without the use of laxatives.

Insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

IBS and subtype of IBS was defined using modified Rome III criteria.34 The definition applied required recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort more than six times per year that had to have at least two of the following:

Relief with defecation

Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool

Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.

IBS was sub-typed as (a) diarrhea-predominant (D-IBS): IBS with loose or watery stools at least 25% and hard or lumpy stool <25% of bowel movements; (b) constipation-predominant (C-IBS): IBS with hard or lumpy stool at least 25% and loose or watery stools <25% of bowel movements; (c) mixed IBS (M-IBS): meet the criteria for both IBS-D and IBS-C; (d) un-subtyped IBS (U-IBS): IBS but not meeting the criteria for the other three categories.34

Ascertainment of cases and controls and data collection

The responses of the subjects on the mailed surveys were used to identify all subjects with chronic constipation. For each case, a single control was randomly selected from the set of remaining respondents who did not have chronic constipation on the current survey that matched the case on age, gender and initial year of medical institution registration. Among a total of 3831 subjects, 1189 subjects who met the sensitive criteria for chronic constipation and 1189 matched controls were identified for the current study (Figure 1). We then abstracted the comprehensive medical records of each of these subjects using a standardized abstract form to identify diagnoses of chronic constipation comorbidities with blinding of case and control status (Tables 1 and 2). Among a total of 2378 subjects that had data abstracted for the current study, 307 subjects who met more specific criteria for chronic constipation were identified. Finally, 262 constipated subjects (after excluding 45 subjects with IBS-C) and age-gender matched 262 controls were used for the matched analysis (Figure 1). As this is not considered sufficiently reliable in our setting, medication data were not collected for the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the current study population. CC: chronic constipation.

Table 1.

The distribution of gastrointestinal comorbid conditions in cases with the specific definition of chronic constipation and controls

| Gastrointestinal comorbid conditions | Chronic constipation n = 262 (%) | Matched controls n = 262 (%) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhoids | 59 (23%) | 49 (19%) | 0.34 |

| Anal fissures | 7 (3%) | 8 (3%) | 1.00 |

| Rectocele | 10 (4%) | 13 (5%) | 0.66 |

| Anal or rectal cancer | 3 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 1.00 |

| Fecal incontinence | 2 (1%) | 7 (3%) | 0.18 |

| Colon cancer | 3 (1%) | 5 (2%) | 0.73 |

| Enterocele/sigmoidocele | 3 (1%) | 8 (3%) | 0.23 |

| Diverticulosis | 91(35%) | 85 (32%) | 0.61 |

| Diverticulitis | 13 (5%) | 15 (6%) | 0.85 |

| Small bowel/colonic stricture/stenosis | 2 (1%) | 8 (3%) | 0.11 |

| IBSb | 13 (5%) | 21(8%) | 0.23 |

| Ischemic colitis | 4 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 1.00 |

| Microscopic colitis | 0 | 3 (1%) | 0.04 |

| Crohn’s disease | 1 (0.4%) | 1(0.4%) | 1.00 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1%) | 0.63 |

| Prior cancer | 88 (34%) | 89 (34%) | 1.00 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 4 (1.5%) | 3 (1%) | 1.00 |

| Anal surgery | 6 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 0.51 |

| Colonic surgery | 8 (3%) | 11 (4%) | 0.65 |

| Cholecystectomy | 14 (5%) | 15 (6%) | 1.00 |

| Abdominal hernia | 7 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 0.55 |

IBS: irritable bowel syndrome.

The univariate association with comorbidities was assessed using McNemar’s test in an analysis accounting for the matching (a total of 262 matched pairs (cases and controls)).

IBS diagnosis was from chart abstraction not from survey data.

Table 2.

The distribution of non-gastrointestinal comorbid conditions in cases with the specific definition of chronic constipation and matched controls

| Condition | Chronic constipation n = 262 (%) | Matched controls n = 262 (%) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological diseases | 71 (27%) | 52 (20%) | 0.07 |

| Stroke | 13 (5%) | 13 (5%) | 1.00 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 11 (4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.006 |

| Other neurological disorders | 59 (23%) | 46 (18%) | 0.19 |

| Metabolic diseases | 85 (32%) | 66 (25%) | 0.07 |

| Diabetes | 43 (16%) | 41 (16%) | 0.90 |

| Hypothyroidism | 51 (19%) | 37 (14%) | 0.10 |

| Others metabolic diseases | 4 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 1.00 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 102 (39%) | 94 (36%) | 0.50 |

| Myocardial infarction | 28 (11%) | 22 (8%) | 0.45 |

| Angina | 81 (31%) | 68 (26%) | 0.22 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 64 (24%) | 59 (23%) | 0.65 |

| Hypertension | 150 (57%) | 149 (57%) | 1.00 |

| Hypercholesterolemia or hypertriglyceridemia | 154 (59%) | 150 (57%) | 0.78 |

| Psychiatric diseases | 82 (31%) | 74 (28%) | 0.50 |

| Psychosis | 2 (1%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1.00 |

| Depression | 68 (26%) | 54 (21%) | 0.16 |

| Anxiety | 43 (16%) | 40 (15%) | 0.81 |

| Eating disorders | 1 (0.4%) | 9 (3%) | 0.02 |

| Urological diseases | 49 (32%) | 36 (24%) | 0.12 |

| Urinary incontinence | 38 (15%) | 28 (11%) | 0.21 |

| Urgency | 21(8%) | 18 (7%) | 0.74 |

| Other | 30 (20%) | 21 (14%) | 0.23 |

| Gynecological conditions | 33 (22%) | 38 (25%) | 0.60 |

| Hysterectomy | 32 (12%) | 35 (13%) | 0.79 |

| Uterine prolapse | 4 (2%) | 9 (3%) | 0.27 |

The univariate association with comorbidities was assessed using McNemar’s test in an analysis accounting for the matching (a total of 262 matched pairs (cases and controls)).

Statistical analyses

Using the bowel disease questionnaire and the data abstracted from the medical records of each case and control, demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with chronic constipation and controls were summarized. A total of 2378 subjects had data abstracted for the current study, although 2327 were used in the analysis after removing 51 controls that were later identified with IBS-C. Of 1189 subjects with chronic constipation by the sensitive (broad) definition, 307 subjects who met more specific criteria for chronic constipation were identified (45 of these met criteria for IBS-C). The age- and sex-specific proportions of chronic constipation in the community, based on the more specific criteria, were estimated (95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on the binomial distribution). Using the age- and sex-specific population totals for Olmsted County residents ≥25 on 31 January 2009, sex-specific age-adjusted prevalence rates were calculated by direct adjustment to the corresponding age and sex distribution of US whites (US census 2000). The 95% CI for the adjusted prevalence rate of chronic constipation assumed a binomial distribution of cases.

A total of 307 subjects with chronic constipation by the specific definition and the remaining 2020 subjects (Figure 1) were used in the logistic regression models, which ignored the matching but included age and gender as covariates; a separate model was examined to assess the association of chronic constipation with each characteristic (i.e. co-morbidity). The odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs were estimated from the coefficients in the logistic regression models. Among a total of 307 subjects with chronic constipation who met the specific definition, 262 constipated subjects were used for the matched analysis after excluding 45 subjects with IBS-C in cases and their matched controls (Figure 1). McNemar’s test was used to assess the univariate associations of case-control status with each comorbidity, based on the 262 constipated subjects and the 262 matched controls.

Sample size assessment

McNemar's test (α = 0.05, two-sided, power ∼80%) was used to assess the differences in the proportions of cases (vs controls) that exhibited various co-morbid conditions. This test was based on the number of discordant pairs (which ranged from <10 to 110), and essentially tested whether the proportion of discordant pairs in favor of cases differs from the null hypothesis of 0.5 (i.e. 50%). The null hypothesis was that the proportion of discordant pairs in favor of cases equals 0.5. For example, with 50 discordant pairs, there was 80% power to detect a departure from 0.5 of ≥ 0.70, and for 90 discordant pairs, a departure of ≥ 0.65.

Results

A completed questionnaire was returned by 3831 subjects (response rate 48%). A total of 50% of females and 45% of males responded, with the mean (±standard deviation (SD)) age of respondents being 61 (±16) and non-respondents 53 (±18) years. Using a logistic regression model for response (yes/no), females and older subjects had slightly greater odds for response (OR (95% CI), females relative to males = 1.20 (1.10–1.31), OR (95% CI) per 10 years of age = 1.30 (1.26–1.33)).

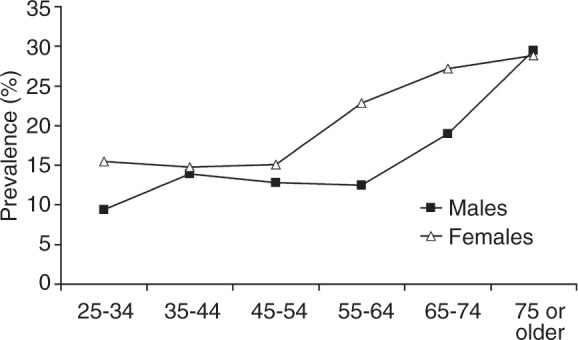

There were 307 subjects who met the specific criteria for chronic constipation based on the BDQ. Figure 2 shows the age- and sex-specific prevalence of chronic constipation. The age-adjusted prevalence per 100 in females was 8.7 (95% CI 7.1–10.3) and in males 5.1 (95% CI, 3.6–6.7); an increasing prevalence of constipation was observed with increasing age (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The prevalence of chronic constipation according to age and gender.

Matched analysis for comorbid conditions

Among 307 subjects with chronic constipation, 262 subjects and 262 matched controls were included in the matched analysis. Table 1 summarizes the distribution of gastrointestinal comorbid conditions in subjects with chronic constipation and their matched controls. Most GI comorbid conditions were not associated with case-control status, with the exception that microscopic colitis was significantly more common in the cases but affected only 1%. Table 2 shows the distribution of non-gastrointestinal comorbid conditions in subjects with chronic constipation and matched controls. Most of the non-gastrointestinal disorders were not associated with case-control status, but Parkinson’s disease was more common in cases compared to controls.

Logistic regression models

Of the total 2378 subjects, 307 subjects who met the more specific criterion of chronic constipation and 2020 who did not meet this specific criterion were included to assess the associations of constipation status with comorbid conditions adjusting for age and gender. Table 3 summarizes the distribution of gastrointestinal comorbid conditions in subjects with chronic constipation and controls. Constipation status was not associated with the majority of gastrointestinal comorbid conditions including hemorrhoids, anal fissures, diverticulosis or diverticulitis, but the odds for chronic constipation were increased in subjects with anal surgery relative to those without (OR = 3.3, 95% CI 1.2–9.1).

Table 3.

Observed proportions of gastrointestinal comorbid conditions in cases with the specific definition of chronic constipation (CC) vs all remaining subjects including non-CC controls (odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI))

| Gastrointestinal comorbid conditions | Cases n = 307 (13%) | Controls n = 2020 (87%) | OR (95% CI)a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhoid | 67 (16%) | 363 (84%) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 0.48 |

| Anal fissure | 8 (14%) | 48 (86%) | 1.1 (0.5–2.3) | 0.87 |

| Rectocele | 13 (22%) | 45 (78%) | 1.3 (0.7–2.5) | 0.43 |

| Anal or rectal cancer | 3 (43%) | 4 (57%) | 4.7 (1.0–22.2) | 0.049 |

| Fecal incontinence | 2 (5%) | 36 (95%) | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) | 0.06 |

| Colon cancer | 4 (19%) | 17 (81%) | 1.2 (0.4–3.7) | 0.73 |

| Enterocele/sigmoidocele | 3 (11%) | 25 (89%) | 0.6 (0.2–1.9) | 0.34 |

| Diverticulosis | 105 (16%) | 564 (84%) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.79 |

| Diverticulitis | 14 (14%) | 85 (86%) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.67 |

| Small bowel/colonic stricture/stenosis | 3 (6%) | 43 (94%) | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 0.10 |

| IBSb | 15 (12%) | 107 (88%) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.30 |

| Ischemic colitis | 5 (31%) | 11 (69%) | 2.2 (0.7–6.4) | 0.15 |

| Microscopic colitis | 1 (7%) | 14 (93%) | 0.4 (0.1–3.2) | 0.39 |

| Crohn’s disease | 1 (10%) | 9 (90%) | 0.8 (0.1–6.2) | 0.80 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1 (8%) | 11 (92%) | 0.5 (0.1–4.1) | 0.54 |

| Prior cancer | 109 (17%) | 527 (83%) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.23 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 5 (18%) | 23 (82%) | 1.2 (0.5–3.3) | 0.70 |

| Celiac disease | 2 (22%) | 7 (78%) | 2.0 (0.4–9.9) | 0.40 |

| Anal surgery | 6 (33%) | 12 (67%) | 3.3 (1.2–9.1) | 0.02 |

| Colonic surgery | 8 (12%) | 61 (88%) | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | 0.36 |

| Cholecystectomy | 16 (13%) | 109 (87%) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.42 |

| Abdominal hernia | 8 (17%) | 38 (83%) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 0.55 |

| Any abdominal surgery | 63 (15%) | 364 (85%) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 0.82 |

IBS: irritable bowel syndrome.

ORs (95% CI) for comorbid conditions in subjects with constipation v. without constipation, adjusted for age and gender.

IBS diagnosis was from chart abstraction (not from survey data).

Table 4 summarizes the distribution of non-gastrointestinal comorbid conditions in those with constipation vs those without constipation. No association with constipation status was detected for most of the non-gastrointestinal comorbid conditions including psychiatric, gynecological, and metabolic disease. However, several neurological diseases including Parkinson’s disease (OR = 6.5, 95% CI 2.9–14.4), multiple sclerosis (OR = 5.5, 95% CI 1.9–15.8), and other neurological disease (OR = 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.8), showed significantly increased odds for chronic constipation, adjusting for age and gender. In addition, modestly increased odds for chronic constipation in those with angina (OR = 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.9) and myocardial infarction, (OR = 1.5, 95% CI 1.0–2.4) were observed adjusting for age and gender. Finally, odds for depression (OR = 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.7), anxiety (OR = 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.8), and hysterectomy (OR = 1.5 95% CI 1.0–2.2) were increased in each instance relative to those without the condition, after adjusting for age and gender.

Table 4.

Observed proportions of non-gastrointestinal comorbid conditions in cases with the specific definition of chronic constipation (CC) vs all remaining subjects including non-CC controls

| Non-gastrointestinal comorbid conditions | Cases n = 307 (13%) | Controls n = 2020 (87%) | OR (95% CI)a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological diseases | 83 (19%) | 361 (81%) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 0.011 |

| Stroke | 14 (18%) | 66 (82%) | 1.0 (0.6–1.9) | 0.89 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 14 (54%) | 12 (46%) | 6.5 (2.9–14.4) | <0.01 |

| Dementia | 7 (27%) | 19 (73%) | 1.7 (0.7–4.3) | 0.23 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 7 (47%) | 8 (53%) | 5.5 (1.9–15.8) | 0.001 |

| Other neurological disorders | 64 (17%) | 303 (83%) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 0.09 |

| Metabolic diseases | 100 (19%) | 427 (81%) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.008 |

| Diabetes | 49 (18%) | 229 (82%) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 0.16 |

| Hypothyroidism | 60 (21%) | 232 (79%) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 0.03 |

| Hypercalcemia | 2 (15%) | 11 (85%) | 1.0 (0.2–4.4) | 0.96 |

| Hyperuricemia | 2 (8%) | 22 (92%) | 0.5 (0.1–2.3) | 0.38 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 122 (18%) | 549 (82%) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 0.004 |

| Myocardial infarction | 30 (21%) | 111 (79%) | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) | 0.055 |

| Angina | 95 (19%) | 418 (81%) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.009 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 76 (19%) | 332 (81%) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 0.051 |

| Hypertension | 171 (16%) | 911 (84%) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 0.58 |

| Hypercholesterolemia or hypertriglyceridemia | 176 (15%) | 993 (85%) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 0.48 |

| Psychiatric diseases | 99 (16%) | 505 (84%) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.049 |

| Psychosis | 3 (25%) | 9 (75%) | 1.8 (0.5–7.0) | 0.37 |

| Depression | 82 (17%) | 407 (83%) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.065 |

| Anxiety | 53 (17%) | 265 (83%) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.12 |

| Eating disorders | 2 (6%) | 31 (94%) | 0.4 (0.1–1.7) | 0.22 |

| Urological diseases | 58 (21%) | 212 (79%) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 0.051 |

| Urinary incontinence | 43 (20%) | 171 (80%) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 0.33 |

| Stress incontinence | 29 (20%) | 118 (80%) | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 0.45 |

| Urinary urgency | 26 (20%) | 104 (80%) | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | 0.49 |

| Recurrent urinary infection | 5 (20%) | 20 (80%) | 1.2 (0.4–3.3) | 0.70 |

| Gynecological conditions | 44 (21%) | 164 (79%) | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) | 0.069 |

| History of hysterectomy | 43 (22%) | 153 (78%) | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 0.033 |

| Uterine prolapse | 6 (13%) | 40 (87%) | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 0.35 |

Odds ratios (ORs) (95% confidence interval (CI)) for comorbid conditions in subjects with constipation vs without constipation, adjusted for age and gender.

Discussion

In this study, the age- and gender-adjusted prevalence of chronic constipation based on specific criteria in the community was estimated to be seven per 100 person years. This is one of the first studies to present US data on constipation and its comorbidities in the general population, and we found that subjects with chronic constipation are about 5-6 times more likely to have Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis, and experienced a two-fold higher rate of anal surgery. Subjects with chronic constipation were also more likely to have ischemic heart disease and depression or anxiety but the odds were all less than two-fold increased. Notably, we did not find any association between constipation status and most of other comorbid conditions.

Constipation is one of the most common digestive disorders in the USA; however, few data are available describing constipation and its comorbidities, and the published data are largely in abstract form only.35–37 The high medical costs associated with constipation indirectly suggest that there may be significant comorbid conditions that drive up costs, but these are poorly characterized in the community. Most studies of comorbid conditions thought to be related to constipation have focused on anorectal and colonic disorders. Singh et al.35 studied comorbidities in patients with constipation using the California Medicaid (MediCal) program. They observed that intestinal impaction, anal fissure, hemorrhoids, volvulus, intestinal obstruction, and irritable bowel syndrome were higher in subjects with constipation. In another study, Singh et al.36 showed a higher prevalence of lower gastrointestinal disorders including fecal impaction, volvulus, anal fissure, diverticular disease, or IBS after a diagnosis of constipation relative to before a diagnosis of constipation. In another study using insurance claims from a US health plan, Mitra et al.4 showed that patients with constipation had a significantly greater likelihood of intestinal impaction, anal fissures, hemorrhoids, volvulus, intestinal obstruction, and rectal ulcers during the post-index period compared to pre-index. All three previous studies appear to have major inherent limitations, being based on a diagnosis code from a medical claim or a Medicaid program; such diagnosis codes may be incorrectly coded or included as a rule-out criterion rather than actual disease. Furthermore, other studies20,21,38,39 have observed no significant association between constipation and lower gastrointestinal comorbidities, including hemorrhoids and fecal incontinence. In our study, we also failed to find any significant association between constipation status and most lower gastrointestinal comorbid conditions, except for anal surgery. This association may also be explained by constipation occurring post anal surgery rather than predisposing to increased surgical rates.

Of major interest, the current study showed a higher prevalence of neurological comorbid conditions, cardiovascular diseases, and psychiatric disease in the logistic regression models. Specifically, neurological diseases including Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis (MS) showed a significant association with constipation status in the current study. Interestingly, it has been suggested that constipation may precede the appearance of motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, but this may be explained by Parkinson’s disease beginning in the enteric nervous system with the initial manifestation being constipation.13,15,40 For example, Savica et al.15 showed that constipation was more common in cases with Parkinson’s disease compared to controls, and the association remained significant in analyses restricted to constipation documented 20 or more years before the onset of motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. The current study also is consistent with this finding. Moreover, gastrointestinal symptoms are known to be common in MS, and more than half of patients with MS have constipation.41,42 Indeed, several case reports14,43 have reported that constipation is an early symptom of MS. In our study, both MS and Parkinson’s disease were diagnosed before the date of the current study survey, but due to the cross-sectional retrospective design, causality cannot be definitively ruled in.

We also observed that several other non-gastrointestinal diseases including cardiovascular disease, depression, and anxiety showed a significant association with constipation status in the logistic regression models. Recently, Hillila et al.44 studied depression as a comorbid feature with gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population. They reported that depressive symptoms are associated with a high rate of GI symptoms, specifically a 1.6 times higher prevalence of constipation compared to patients without depressive symptoms. Moreover, Mussell et al.45 showed that GI symptoms are significantly associated with depression and anxiety in primary care. Notably, antidepressant agents have effects on gastrointestinal function including gut motility or sensitivity46–48 and are prescribed for the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders.46,48 Thus, medication use for depression or anxiety might play a role in these associations. Constipation might be linked to heart disease because of constipating medication use, but a link between constipation and cardiovascular disease was also observed in a large study of postmenopausal women from the Women’s Health Initiative; among 73,047 women, those with severe constipation had a 23% increased risk of cardiovascular events adjusting for possible confounders including medications.49

The strengths of the current study include the investigation of a random community sample. The subjects were not necessarily seeking health care for their gastrointestinal complaints, which should have minimized selection bias, and this sample provided an excellent opportunity to study the real relationship between constipation status and comorbid conditions. With regard to limitations, we may not have identified all relevant comorbid conditions because the current study was based on medical chart and not a systematic examination, and we may have underestimated the prevalence of comorbidities, specifically anal fissure or hemorrhoids. However, the current study matched the controls with cases in terms of age, gender, and registration year, and thus the detection of comorbid conditions applied similarly to cases and controls. Our study had a moderate sample size but it should have been sufficient to detect clinically important associations. We started with a survey and then did a chart review; the chart review provides a level of accuracy not obtained from an electronic database. The response rate was 48% in this study but we have shown based on detailed chart reviews that non-response bias in this population is very unlikely.50 The associations with ORs < 2 (e.g. cardiovascular disease, anxiety and depression), however, may reflect uncontrolled confounding (e.g. chronic medication use) and need to be treated with particular caution. The prevalence of chronic constipation may vary by ethnic group, but at a minimum our data are likely generalizable to the US white population (as Olmsted County is in terms of Caucasians socio-demographically very similar to the entire US population).23,24

We conclude from this population-based study that most of the comorbid conditions studied were similarly distributed between chronic constipation and controls. Thus, overall our data highlight that most people with chronic constipation in the community do not have a significantly increased risk of GI comorbid conditions despite traditional medical teaching to the contrary, but Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis are very strongly linked to constipation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Lori R Anderson for her assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceuticals. This study was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 AG034676. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

NJ Talley and Mayo Clinic have licensed the Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.O'Keefe EA, Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Bowel disorders impair functional status and quality of life in the elderly: A population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995; 50: M184–M189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci 1989; 34: 606–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Epidemiology of constipation in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum 1989; 32: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitra D, Davis KL, Baran RW. Healthcare costs and clinical sequelae associated with constipation in a managed care population. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: S432–S432. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Locke GR 3rd, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterology 2000; 119: 1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: S5–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin BC, Barghout V, Cerulli A. Direct medical costs of constipation in the United States. Manag Care Interface 2006; 19: 43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Lillo AR, Rose S. Functional bowel disorders in the geriatric patient: Constipation, fecal impaction, and fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 901–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dukas L, Platz EA, Colditz GA, et al. Bowel movement, use of laxatives and risk of colorectal adenomatous polyps among women (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2000; 11: 907–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dukas L, Willett WC, Colditz GA, et al. Prospective study of bowel movement, laxative use, and risk of colorectal cancer among women. Am J Epidemiol 2000; 151: 958–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talley NJ, Fleming KC, Evans JM, et al. Constipation in an elderly community: A study of prevalence and potential risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91: 19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talley NJ, Jones M, Nuyts G, et al. Risk factors for chronic constipation based on a general practice sample. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 1107–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrne KG, Pfeiffer R, Quigley EM. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. A report of clinical experience at a single center. J Clin Gastroenterol 1994; 19: 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chellingsworth M. Constipation as a presenting symptom of multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2003; 362: 1941–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savica R, Carlin JM, Grossardt BR, et al. Medical records documentation of constipation preceding Parkinson disease: A case-control study. Neurology 2009; 73: 1752–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stollman N, Raskin JB. Diverticular disease of the colon. Lancet 2004; 363: 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alonso-Coello P, Mills E, Heels-Ansdell D, et al. Fiber for the treatment of hemorrhoids complications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pigot F, Siproudhis L, Allaert FA. Risk factors associated with hemorrhoidal symptoms in specialized consultation. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2005; 29: 1270–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corby H, Donnelly VS, O'Herlihy C, et al. Anal canal pressures are low in women with postpartum anal fissure. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 86–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, et al. Risk factors for fecal incontinence: A population-based study in women. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. Constipation is not a risk factor for hemorrhoids: A case-control study of potential etiological agents. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89: 1981–1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am 1981; 245: 54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc 1996; 71: 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, et al. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: Half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clinic Proc 2012; 87: 1202–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, et al. Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: A population-based study. Gastroenterology 1992; 102: 1259–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Van Dyke C, et al. Epidemiology of colonic symptoms and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1991; 101: 927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton J, 3rd, et al. A patient questionnaire to identify bowel disease. Ann Intern Med 1989; 111: 671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talley NJ, O'Keefe EA, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: A population-based study. Gastroenterology 1992; 102: 895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidemiol 1992; 136: 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rey E, Locke GR 3rd, Jung HK, et al. Measurement of abdominal symptoms by validated questionnaire: A 3-month recall timeframe as recommended by Rome III is not superior to a 1-year recall timeframe. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31: 1237–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, et al. Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: The bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc 1990; 65: 1456–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, et al. A new questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69: 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reilly WT, Talley NJ, Pemberton JH, et al. Validation of a questionnaire to assess fecal incontinence and associated risk factors: Fecal Incontinence Questionnaire. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 146–153; discussion 53–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh G, Kahler KH, Bharathi V, et al. Constipation in adults: Complications and comorbidities. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: A154–A154. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh G, Vadhavkar S, Wang H, et al. Complications and comorbidities of constipation in adults. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: A458–A458. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talley NJ, Lasch KL, Baum CL. A gap in our understanding: Chronic constipation and its comorbid conditions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation. An epidemiologic study. Gastroenterology 1990; 98: 380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johanson JF, Irizarry F, Doughty A. Risk factors for fecal incontinence in a nursing home population. J Clin Gastroenterol 1997; 24: 156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueki A, Otsuka M. Life style risks of Parkinson's disease: Association between decreased water intake and constipation. J Neurol 2004; 251: vII18–vII23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fowler CJ, Henry MM. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Semin Neurol 1996; 16: 277–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hinds JP, Eidelman BH, Wald A. Prevalence of bowel dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. A population survey. Gastroenterology 1990; 98: 1538–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawthom C, Durdey P, Hughes T. Constipation as a presenting symptom. Lancet 2003; 362: 958–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hillila MT, Hamalainen J, Heikkinen ME, et al. Gastrointestinal complaints among subjects with depressive symptoms in the general population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 28: 648–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mussell M, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms in primary care: Prevalence and association with depression and anxiety. J Psychosom Res 2008; 64: 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grover M, Drossman DA. Psychotropic agents in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2008; 8: 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galligan JJ, Parkman H. Recent advances in understanding the role of serotonin in gastrointestinal motility and functional bowel disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007; 19: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kindt S, Tack J. Mechanisms of serotonergic agents for treatment of gastrointestinal motility and functional bowel disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007; 19: 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salmoirago-Blotcher E, Crawford S, Jackson E, et al. Constipation and risk of cardiovascular disease among postmenopausal women. Am J Med 2011; 124: 714–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choung RS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, et al. A low response rate does not necessarily indicate non-response bias in gastroenterology survey research: A population-based study. J Public Health 2013; 21: 87–95. [Google Scholar]