Abstract

Trauma laparotomy after blunt abdominal trauma is conventionally indicated for patients with features of hemodynamic instability and peritonitis to achieve control of hemorrhage and control of spillage. In addition, surgery is clearly indicated for the repair of posttraumatic diaphragmatic injury with herniation. Some other indications for laparotomy have been presented and discussed. Five patients with blunt abdominal injury who underwent laparotomy for nonroutine indications have been presented. These patients were hemodynamically stable and had no overt signs of peritonitis. Three patients had solid organ (spleen, kidney) infarction due to posttraumatic occlusion of the blood supply. One patient had mesenteric tear with internal herniation of bowel loops causing intestinal obstruction. One patient underwent surgery for traumatic abdominal wall hernia. In addition to standard indications for surgery in blunt abdominal trauma, laparotomy may be needed for vascular thrombosis of end arteries supplying solid organs, internal or external herniation through a mesenteric tear or anterior abdominal wall musculature, respectively.

Keywords: Abdomen, blunt, indications, internal hernia, laparotomy, trauma, traumatic abdominal wall hernia, vascular injury

INTRODUCTION

Blunt abdominal trauma warranting emergent laparotomy has conventionally been indicated in patients presenting with hypotension for hemorrhage control, solid organ injury, features of peritonitis following blunt or penetrating abdominal injury or due to diaphragmatic injury.[1,2] The decision to do a laparotomy is taken based on the hemodynamic status of the patient in conjunction with examination of the abdomen, Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) exam, and computed tomography (CT) scan. But this does not cover the entire spectrum of indications for laparotomy in a case of blunt abdominal trauma.

CASE REPORTS

We present five patients with blunt abdominal injury who underwent semi-emergent laparotomy for nonroutine indications. These patients were hemodynamically stable and had no overt signs of peritonitis.

Case 1

A 36-year-old male presented after a road traffic accident (RTA) with blunt abdomen injury and a right tibiofibular fracture. He has the pulse of 72/min and blood pressure (BP) of 112/70 mm Hg with a normal FAST exam. The patient was transferred to the orthopedic unit for further management but developed complaints of vomiting and constipation with abdominal distension over the next 3 days. Abdominal X-ray [Figure 1] revealed multiple air fluid levels and a contrast CT with oral and intravenous (IV) contrast revealed an obstruction at the jejunoileal junction. A decision was taken to do a diagnostic laparoscopy on day 4 after injury, which was converted to open laparotomy due to findings of internal herniation of ileal loops through the transverse mesocolon. This herniated ileal loop had vascular compromise so it was resected, and an ileo-ileal end to end anastomosis was done. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 7.

Figure 1.

X-ray showing multiple air fluid levels in a patient with internal herniation

Case 2

A 50-year-old male presented a day after sustaining blunt abdominal injury by a bull horn to the right side of his abdomen. He presented with right lower abdominal swelling. He was hemodynamically stable with a pulse of 82/min and a BP of 130/90 mm Hg. A chest X-ray diagnosed a right simple pneumothorax for which a chest tube was inserted. FAST exam was normal, but contrast CT revealed herniation of bowel through a defect in the anterior abdominal wall [Figure 2]. 3 days after injury, an exploratory laparotomy was done which showed no associated intraperitoneal injury and the hernia was reduced, and the defect reinforced with a mesh. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 7.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan showing traumatic abdominal wall hernia

Case 3

A 23-year-old male presented with deceleration injury following an RTA. His hemodynamic parameters were within the normal range; he had a pulse of 80/min and a BP of 110/78 mm Hg. Examination revealed a soft abdomen. The FAST exam was positive, and a CT with oral and IV contrast revealed a completely devascularized spleen. The patient was conservatively managed and started on a liquid diet but developed abdominal pain with associated fever after a week. An exploratory laparotomy was done 8 days after injury, and a splenectomy was done for splenic infarction with abscess formation. He had an uneventful postoperative period and went home on postoperative day 7.

Case 4

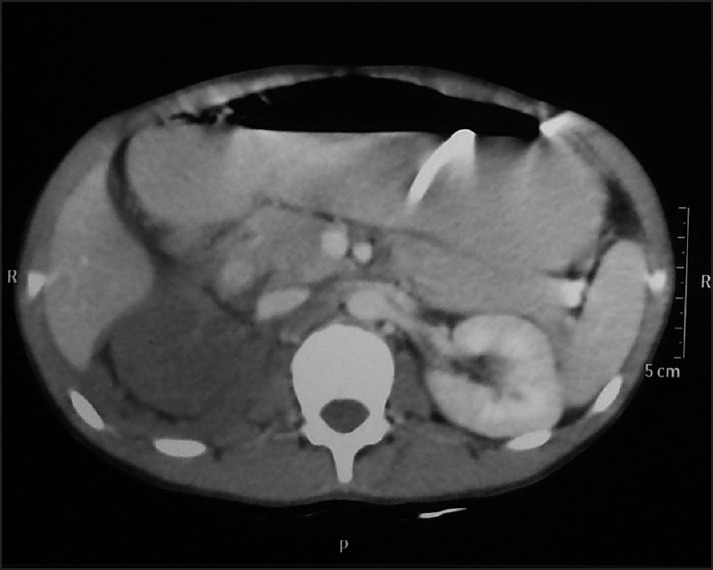

A 9-year-old male child presented with deceleration injury after falling from a height of 12 feet. He had normal hemodynamic parameters with a pulse of 100/min and a BP of 100/70 mm Hg. Examination revealed a soft abdomen. The FAST exam done was positive. A contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) with oral and IV contrast revealed a completely devascularized right kidney [Figure 3]. As the patient had pain and hematuria, a laparotomy was performed 6 days after injury and the right kidney showed infarction, so a right nephrectomy was done. He had an uneventful postoperative period and went home on postoperative day 6.

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing no enhancement of right kidney with no parenchymal injury

Case 5

A 35-year-old male presented with blunt abdominal trauma after an RTA along with injury to left lower limb. His hemodynamic parameters were normal, with a pulse of 100/min and a BP of 110/70 mm Hg. He had generalized abdominal tenderness and guarding. The FAST exam was positive, and X-ray revealed a left shaft of femur fracture. CT with IV contrast revealed no enhancement in both kidneys in the arterial phase suggestive of bilateral renal pedicle injury [Figure 4]. Endovascular stenting of both renal arteries was attempted unsuccessfully the next day after injury. Laparotomy was done 2 days after the injury due to the failure of endovascular stenting, and a right aortorenal artery polytetrafluoroethylene grafting was done on the right side. On the left side, a splenectomy was done, and the splenic artery anastomosed with the left renal artery. Patient underwent repeated dialysis in the postoperative period. His urine output returned to normal but after 4 days, he succumbed due to his injury. Table 1 summarizes all the cases.

Figure 4.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (coronal view) showing nonenhancement of both kidneys without parenchymal injury

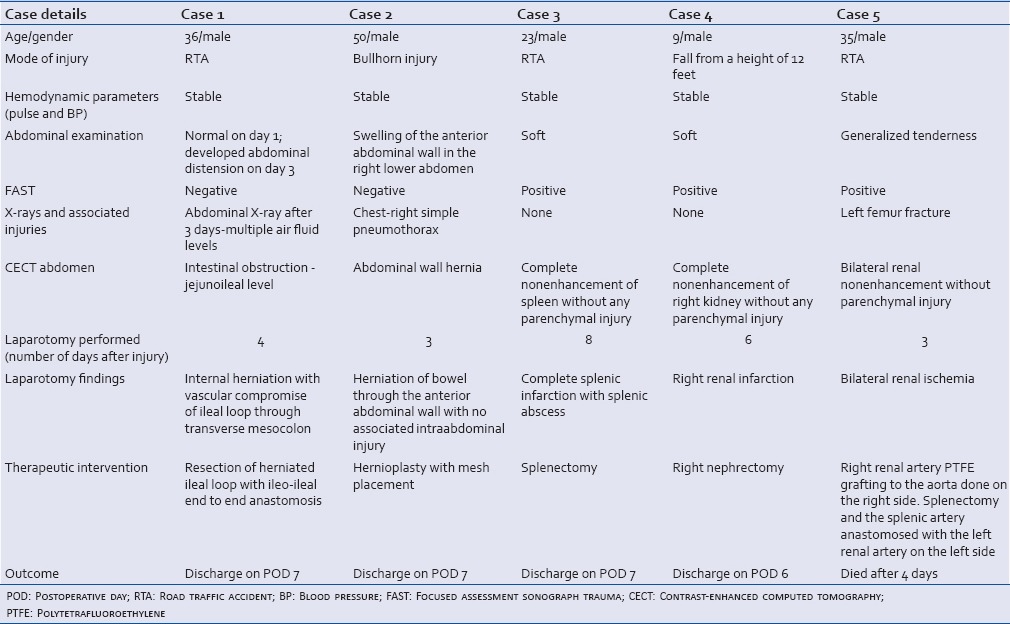

Table 1.

Summary of all cases

DISCUSSION

Alternate possible indications for laparotomy should be kept in mind while managing patients with blunt abdominal trauma. CT with IV and oral contrast has been particularly useful in the diagnosis of both external as well as internal hernias and vascular injuries following trauma.[3]

In addition to diaphragmatic injury and herniation, mesenteric injury with herniation can be missed initially, and the presentation may be delayed. In case of diaphragmatic injuries, the delay has been reported to be months and even years.[4] In this case, although the internal herniation presented during the same hospital stay; Aref and Felemban have reported it to present 7 months later.[5] The role of laparoscopy in blunt trauma is limited. It is useful in the diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia.[6] The authors used laparoscopy in the diagnosis of post traumatic internal herniation of the bowel. This internal herniation occurred through a defect after a traumatic mesenteric tear. Such an injury affecting the end artery supplying the corresponding part of the intestine resulting in devascularization of that segment will lead to the patient presenting earlier with signs of peritonitis. These injuries manifests as vascular engorgement with wall thickening on CT scan and may be missed unless specifically looked for.[7]

Traumatic abdominal wall hernia (TAWH) is a rare entity with <50 reported cases. TAWH is diagnosed by the onset of the hernia through the damaged muscle and fascia after blunt abdominal trauma with intact overlying skin.[8] Unlike the case of internal herniation, the patient with TAWH in this series presented with an obvious external swelling. However, there are reports that the swelling may not always be clinically apparent.[9] On operation, the defect was not as well-delineated as with conventional abdominal wall hernia surgery. It was accompanied by local hematoma and contusion of the affected muscle. Therefore, the defect was reinforced with a prosthetic mesh after the closure. Exploratory laparotomy in the immediate period with surgical repair of the hernia with meshplasty is a tested form of treatment in the presence of a clinically apparent hernia.[9] The key concern in TAWH is the presence of associated injuries like the small bowel or large bowel injuries as well as solid organ injuries which can be detected by either CT scan or during exploratory laparotomy. In the absence of intraabdominal contamination due to bowel injury, a meshplasty can be performed to reinforce the defect especially if it is large. In the presence of a contaminated field, the use of a biological mesh can be considered to reduce the risk of postoperative infection.[10] In case of small defects, the TAWH can be closed primarily.[11]

Splenic infarction is commonly seen associated with hematological conditions, collagen vascular disease, and nonhematological malignancies.[12] Splenic infarction following blunt abdominal trauma is a rare presentation which can be diagnosed using CECT abdomen.[13] It is diagnosed by nonenhancement of the spleen with IV contrast during CECT abdomen. Patients with segmental splenic infarction can have resolution identified by repeat CT scan with no need for any surgical intervention while patients who develop complications like abscess or delayed rupture may need angiographic or surgical intervention.[13]

Renal artery injuries are associated with rapid deceleration injuries which may lead to tears in the intima followed by thrombosis of the blood which enters the vessel wall.[14] Higher grades of injury following renal artery trauma are adverse prognostic factors for kidney survival and warrant nephrectomy if there is a contralateral functioning kidney.[15] In case an infarcted kidney is managed conservatively, there is a possibility of complications like perinephric abscess formation (which can be treated with percutaneous drainage), hypertension which is renin mediated from the ischemic renal tissue and recurrent attacks of hematuria due to formation of arteriovenous fistula (which can be treated by angioembolization).[16] These can be avoided by early nephrectomy, especially in injuries to the corticomedullary junction.[17]

In case of bilateral renal artery injury, an attempt at revascularization must be undertaken. Although angiography is commonly used in hemorrhage control after renal artery injury, in this patient, endovascular intervention was utilized to attempt stenting both renal arteries after injury.[18] As the stenting was not successful, a major bilateral revascularizaiton procedure was undertaken.

CONCLUSION

The common indications for laparotomy in blunt abdominal trauma in hemodynamically stable patients are hollow viscus perforation, solid organ injury and diaphragmatic hernia. In a vitally stable patient, imaging helps in the diagnosis of these conditions as well as uncommon conditions which need laparotomy. CECT scan can help in the diagnosis of internal herniation after mesenteric injury as well as external herniation following injury to the anterior abdominal wall. In addition, CT scan can diagnose vascular injuries to end organs such as the spleen and kidney which lead to infarction without associated parenchymal injury. In case of unilateral renal injury, early nephrectomy is indicated but splenic infarction can be managed conservatively unless a complication like abscess develops for which splenectomy is needed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohamed AA, Mahran KM, Zaazou MM. Blunt abdominal trauma requiring laparotomy in poly-traumatized patients. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox EF. Blunt abdominal trauma. A 5-year analysis of 870 patients requiring celiotomy. Ann Surg. 1984;199:467–74. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198404000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuhlfaut JW, Anderson SW, Soto JA. Blunt abdominal trauma: Current imaging techniques and CT findings in patients with solid organ, bowel, and mesenteric injury. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2007;28:115–29. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rashid F, Chakrabarty MM, Singh R, Iftikhar SY. A review on delayed presentation of diaphragmatic rupture. World J Emerg Surg. 2009;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aref H, Felemban B. Post traumatic acquired multiple mesenteric defects. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:547–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latic F, Delibegovic S, Latic A, Samardzic J, Zerem E, Miskic D, et al. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Med Arh. 2010;64:121–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Filippo M, Sagone C, Zompatori M. Unenhanced MDCT findings of acute bowel ischemia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:W271. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damschen DD, Landercasper J, Cogbill TH, Stolee RT. Acute traumatic abdominal hernia: Case reports. J Trauma. 1994;36:273–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199402000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singal R, Dalal U, Dalal AK, Attri AK, Gupta R, Gupta A, et al. Traumatic anterior abdominal wall hernia: A report of three rare cases. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4:142–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.76832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davey SR, Smart NJ, Wood JJ, Longman RJ. Massive traumatic abdominal hernia repair with biologic mesh. J Surg Case Rep 2012. 2012:12. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjs023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganchi PA, Orgill DP. Autopenetrating hernia: A novel form of traumatic abdominal wall hernia — Case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 1996;41:1064–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199612000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaroch MT, Broughan TA, Hermann RE. The natural history of splenic infarction. Surgery. 1986;100:743–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller LA, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K, Ohson AS. CT diagnosis of splenic infarction in blunt trauma: Imaging features, clinical significance and complications. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:342–8. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan MJ, Stables DP. Renal artery occlusion from trauma. JAMA. 1972;221:1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knudson MM, Harrison PB, Hoyt DB, Shatz DV, Zietlow SP, Bergstein JM, et al. Outcome after major renovascular injuries: A Western trauma association multicenter report. J Trauma. 2000;49:1116–22. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200012000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch TH, Martínez-Piñeiro L, Plas E, Serafetinides E, Türkeri L, Santucci RA, et al. EAU guidelines on urological trauma. Eur Urol. 2005;47:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Husmann DA, Morris JS. Attempted nonoperative management of blunt renal lacerations extending through the corticomedullary junction: The short-term and long-term sequelae. J Urol. 1990;143:682–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whigham CJ, Jr, Bodenhamer JR, Miller JK. Use of the Palmaz stent in primary treatment of renal artery intimal injury secondary to blunt trauma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:175–8. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]