Abstract

Background:

The promotional activities by medical representatives (MRs) of the pharmaceutical companies can impact the prescribing pattern of doctors. Hence, the interaction between doctors and the pharmaceutical industry is coming under increasing scrutiny.

Objective:

The primary objective was to assess the attitude of the doctors toward the interaction with the MRs of the pharmaceutical company. The secondary objective was to assess the awareness of the doctors about regulations governing their interaction with the pharmaceutical company.

Materials and Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study. This study was carried out using a pretested questionnaire containing 10 questions between June and September 2014. The doctors working in the Dhanalakshmi Srinivasan Medical College and Hospital, Perambalur (Tamil Nadu) during the study period was included.

Results:

A total of 100 pretested questionnaires were distributed, and 81 doctors responded (response rate 81%). 37% doctors responded that they interacted with MR once a week whereas 25.9% told that they interact with MRs twice a month. About 69.1% doctors think that MR exaggerate the benefits of medicines and downplays the risks and contraindications of medicine(P = 0.000). 61.7% doctors think that MR has an impact on their prescribing (P = 0.000). 63% doctors stated that they had received promotional tools such as stationery items, drug sample, textbooks or journal reprints from MR in last 12 months (P = 0.0012). Unfortunately, 70.4% doctors have not read the guidelines about interacting with the pharmaceutical industry or its representative (P = 0.000).

Conclusion:

Rather than forbidding any connection between doctors and industry, it is better to establish ethical guidelines. The Medical Council of India code is a step in the right direction, but the majority of doctors in this study have not read the guidelines about interacting with the pharmaceutical industry or its representative.

KEY WORDS: Code of ethics, doctors, drug samples, Medical Council of India guidelines, pharmaceutical industry, prescribing pattern, unethical marketing

Medical representatives (MRs), are the pivotal links between the doctor and the pharmaceutical company. They are the pharmaceutical drug company employee who routinely visit the doctor, and give particulars of company's drug to the doctor and also get feedback for prospective promotional activities. MRs basically builds liaisons with doctors and advocates the company's drugs to doctors. Hence, the interaction between a MR and a doctor is regarded by pharmaceutical companies as an essential part of their marketing blueprint.[1,2]

In fact as reported by previous studies, the interaction between MRs of pharmaceutical companies and doctors are highly ubiquitous. The reported studies have proved that propagative activities by MR of the pharmaceutical companies can impact the prescribing pattern of doctors. Because of this the interaction between doctors and the pharmaceutical industry is coming under increasing exploration.[3,4] The probability that drug companies might be exercising too much influence on clinical decision making of doctors has led to many concerns.[1]

There are many guidelines to prohibit or restrain unethical marketing practices. In India, the Medical Council of India (MCI) has promulgated a code of ethics for the doctor in order to regulate their dealing with the pharmaceutical industry. Although there is the availability of guidelines to prohibit or restrain unethical marketing practices, but there is no legibility on the acquaintanceship among the doctors about the regulations for interacting with the pharmaceutical industry. Furthermore, despite the MCI officially coming up with the guidelines, the average neighborhood doctor is unlikely to be aware of the existence of the rules and the type of reprimand or punishment he is likely to face in the event of a contravention.[5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]

Objectives of the study

The primary objective was to assess the attitude of the doctors toward the interaction with the MRs of the pharmaceutical company. The secondary objective was to assess the awareness of the doctors about regulations governing their interaction with the pharmaceutical company.

Materials and Methods

Setting

This study was conducted at Dhanalakshmi Srinivasan Medical College and Hospital (DSMCH), a Tertiary Care Hospital in Perambalur, Tamil Nadu, India. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of DSMCH, Perambalur. The study period was between June and September 2014.

Study design

A cross-sectional study was carried out using a pretested questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to assess the attitude of the doctors toward the interaction with MRs and to assess the awareness of the doctors about regulations governing their interaction with the pharmaceutical company [Appendix 1]. Pilot testing of the questionnaire was done randomly on 10 doctors of the institute. The questionnaire was finalized after ambiguous, and unsuitable questions were modified based on the result of the pretest.

Participants

The doctors working in the DSMCH, Perambalur (Tamil Nadu) during the study period were included. Only those who gave their consent to participate were included in the study.

Data collection

About 100 pretested questionnaires [Appendix 1] were distributed among the healthcare professionals. A time of 1-day was given for the collection of the anonymously filled forms. Simple random sampling was followed while distributing the questionnaire to the doctors.

Study size

The total number of doctors working in the hospital at the time of the study (population size) was approximately 135. The margin of error was 5% and confidence level was 95%. The expected frequency value of 50% was used as it produces largest sample size. Putting the values of population size, the margin of error, confidence interval and expected frequency value or response distribution, the approximate sample size was found to be 100 approximately.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Statistical Software, version 16, IBM Corporation (Armonk, New York, U.S). One sample t-test between percents was used to compare responses. One sample t-test between percents was performed to determine whether respondents were more likely to prefer one alternative or another. P <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

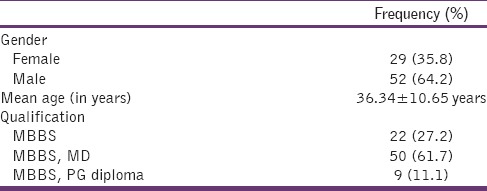

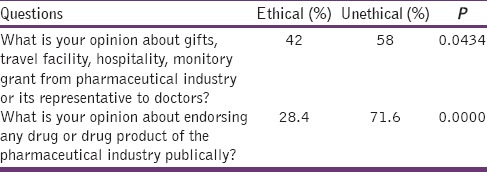

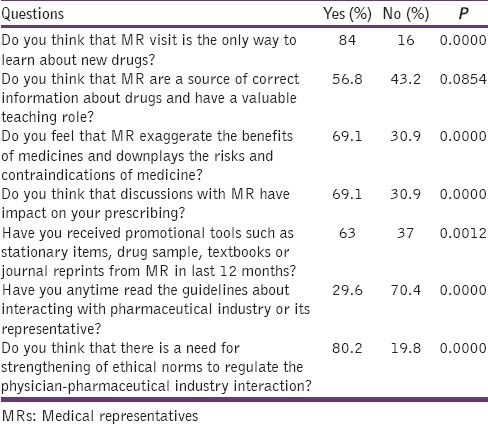

A total of 100 questionnaires were distributed among the doctors and 81 responded (response rate = 81%). Table 1 shows demographic details. 37.0% doctors have stated that they interact with MR of pharmaceutical companies at least once a week, 25.9% doctors have stated that they interact with MR of pharmaceutical companies at least twice a month, 16% doctors have stated that they interact with MRs 2–3 times/week, 12.3% doctors stated that they interact with MR rarely, and 8.6% doctors stated that they interacted with MRs daily. 84% doctors do not think that MR visit is the only way to learn about new drugs but 16% doctors think that MR visit is the only way to learn about new drugs (P = 0.0000). 56.8% doctors think that MR are a source of correct information about drugs and have a valuable teaching role but 43.2% doctors do not think that MR are a source of correct information about drugs and have a valuable teaching role. 69.1% feel that MR exaggerate the benefits of medicines and downplays the risks and contraindications of medicine, whereas 30.9% doctors do not think that MR exaggerate the benefits of medicines and downplays the risks and contraindications of medicine (P = 0.0000). 69.1% doctors think that discussions with MR have an impact on their prescribing, but 30.9% do not think that discussions with MR have an impact on their prescribing (P = 0.0000). 63% doctors stated that they had received promotional tools such as stationery items, drug sample, textbooks, or journal reprints from MR in last 12 months but 37% doctors said that they had not received promotional tools such as stationery items, drug sample, textbooks or journal reprints from MR in last 12 months (P = 0.0012). Only 29.6% doctors stated that they have read the guidelines about interacting with pharmaceutical industry or its representative whereas 70.4% doctors stated that they had not read the guidelines about interacting with pharmaceutical industry or its representative (P = 0.0000). 58% doctors think that it is unethical to accept gifts, travel facility, hospitality, monitory grant from pharmaceutical industry or its representative to doctors whereas 42% doctors think that it is ethical to accept gifts, travel facility, hospitality, monitory grant from pharmaceutical industry or its representative to doctors (P = 0.0434). 71.6% doctors think that it is unethical to endorse any drug or drug product of the pharmaceutical industry publically whereas 28.4% doctors think that it is ethical to endorse any drug or drug product of the pharmaceutical industry publically (P = 0.0000). 80.2% doctors think that there is a need for strengthening of ethical norms to regulate the physician-pharmaceutical industry interaction but 19.8% doctors do not think that there is a need for strengthening of ethical norms to regulate the physician-pharmaceutical industry interaction (P = 0.0000). Tables 2–4 show the abovementioned details.

Table 1.

Demographic details of the participants (n=81)

Table 2.

Response of the doctors on frequency of interaction with MRs of pharmaceutical companies?

Table 4.

Opinion of the doctors towards gifts, travel facility, hospitality, monitory grant and endorsing any drug or drug product of the pharmaceutical industry publically

Table 3.

Attitude of the doctors towards the interaction with MRs and the awareness of the doctors about regulations governing their interaction with the pharmaceutical company

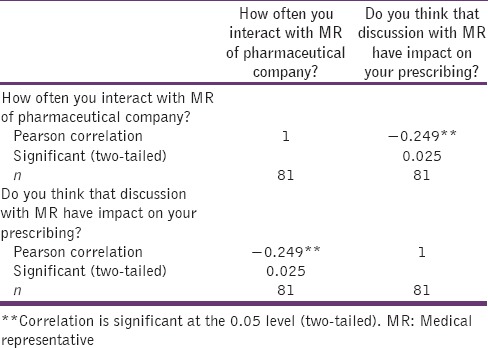

Strength and direction of the degree of association

The correlation between the interaction of doctors with MR of pharmaceutical company and impact on their prescribing was analyzed by using Pearson's correlation coefficient. The strength of correlation between two variables was found to be weak negative. The correlation was significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed) (r = −0.249, n = 81, P = 0.025) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Correlation between interaction with MR of pharmaceutical company and impact on their prescribing

Discussion

The results corroborate that doctors and MRs are in regular contact as a result of MRs visits. Thus, the impact of the pharmaceutical industry on the medical profession cannot be renounced. The pharmaceutical companies have an intelligible desire to persuade doctors to prescribe their products. It corresponded to the 61.7% doctor's recognition that MR has an impact on their prescribing. Similarly in a study by Balhara et al., 47% of the subjects reported that the acceptance of a gift from a pharmaceutical company would affect a clinician's decision. 63.3% doctors told that they had received promotional tools such as stationery items, drug sample, textbooks or journal reprints from MR in last 12 months. The stationery endowments that exhibit the brand name of a particular product can have a substantial impact on a doctor's prescribing choices. Accordingly, the more exposed a doctor is to an endorsed product; the more likely it is to enter prescribing deliberation. These promotional products even influence medical students’ approach toward product brands. Therefore, all prescribers should ratify that even simple endowments are part of a composite marketing design to impact prescribing choices. In addition, an individual's resolve to respond for even frivolous gifts is often undervalued.[5,14,15,16,17,18]

About 69.1% doctors feel that MR exaggerate the benefits of medicines and downplays the risks and contraindications of medicine. Naturally, the drug information package is tailor-made to sell the drug, and hence the benefits are overstated, risks downplayed, and contraindications attenuated. Similarly, the study by Alssageer and Kowalski stated that doctors believe that the outline of the drug information provided by pharmaceutical company representatives is deficient and often overstated.[19] Also, study by Othman et al. concluded that hazard and adverse effects of medicines were often omitted in medicines information provided by pharmaceutical representatives.[20] At the same time, 56.8% doctors in our study think that MRs have an important teaching role. For many doctors, the MR's visits are the only way they learn about new drugs. Many doctors depend on the MR for information on new drugs, the indications, the dosages, why they are better than other similar drugs, and so on. A recently published study found that physicians having greater interactions with pharmaceutical company representatives had more rapid acceptance of new medicines than those working in settings with limited access to sales representatives.[21] It is, therefore, crucial to establish that doctors receive more impartial learning than they are given by means of MR visits or at the academic events organized by pharmaceutical companies. As long as the MRs are the major antecedent of information regarding drug use they will continue to impact the clinical practice of Indian doctors. Unaided academic events will, therefore, have to be encouraged. Similarly, medical journals that are not financed through drug advertising and other drug company support and that provide discerning and unbiased information should be encouraged.[22,23]

It may not be feasible to completely do away with industry interaction. Moreover, the majority of the doctors said that there is there is a need for strengthening of ethical norms to regulate the physician-pharmaceutical industry interaction. So, rather than forbidding any connection between doctors and industry, it is better to establish ethical guidelines for industry sponsorship of conferences, research, and gifts to doctors.[13] In December 2009, MCI rectified the Code of Medical Ethics, which now recommends stringent actions against medical professionals benefitting from pharmaceutical industries. It categorically states that a medical practitioner shall not receive any gift, travel facilities, hospitality from industry. The regulations further provide that a medical practitioner shall not individually receive any cash or monetary grants from industry. The medical practitioners are also forbidden from supporting any drug or product of the industry publically. The regulations, however permit funding for medical research, study, etc., provided it is received by the medical practitioner through approved institution(s). The Indian Pharmaceutical Industry Associations-Indian Drug Manufacturers’ Association and Organization of Pharmaceutical Producers of India - have their own guidelines which emphasize on the ethical promotion of medicines to healthcare professionals.[8] But, 68.3% doctors have not read the guidelines about interacting with the pharmaceutical industry or its representative.

Limitations of the study

The major limitation of this study was the essentially small number of participants. Because of the small sample size, the result of the study cannot be generalized to the whole population. In addition, some other factors that are associated with self-reporting studies such as accuracy of recall, personal bias could also have affected the results of this study in some ways.

Conclusion

The majority of the doctors said that MR influences their prescribing but at the same time majority of the doctor said that MR exaggerates the benefits of medicines and downplays the risks and contraindications of medicine. Rather than forbidding any connection between doctors and industry, it is better to establish ethical guidelines. The MCI code is a step in the right direction, but the majority of doctors in this study have not read the guidelines about interacting with the pharmaceutical industry or its representative.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

I gratefully acknowledge the help of my colleagues in the Department of Pharmacology, DSMCH, Siruvachur, Perambalur - 621 212, Tamil Nadu, India.

Appendix 1: Questionnaire

Age:

Sex:

Qualification:

-

How often you interact with medical representatives (MRs) of pharmaceutical companies?

(a) Daily (b) 2–3 times/week (c) once a week (d) twice a month (e) rarely

-

Do you think that MR visit is the only way to learn about new drugs?

(a) Yes (b) No

-

Do you think that MRs are a source of correct information about drugs and have a valuable teaching role?

(a) Yes (b) No

-

Do you feel that MR exaggerate the benefits of medicines and downplays the risks and contraindications of medicine?

(a) Yes (b) No

-

Do you think that discussions with MR have impact on your prescribing?

(a) Yes (b) No

-

Have you received promotional tools such as stationary items, drug sample, textbooks or journal reprints from MR in last 12 months?

(a) Yes (b) No

-

Have you anytime read the guidelines about interacting with pharmaceutical industry or its representative?

(a) Yes (b) No

-

What is your opinion about gifts, travel facility, hospitality, monitory grant from pharmaceutical industry or its representative to doctors?

(a) It is ethical (b) It is unethical

-

What is your opinion about endorsing any drug or drug product of the pharmaceutical industry publically?

(a) It is ethical (b) It is unethical

Do you think that there is a need for strengthening of ethical norms to regulate the physician-pharmaceutical industry interaction?

(a) Yes (b) No

References

- 1.Morgan MA, Dana J, Loewenstein G, Zinberg S, Schulkin J. Interactions of doctors with the pharmaceutical industry. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:559–63. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.014480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alssageer MA, Kowalski SR. A survey of pharmaceutical company representative interactions with doctors in Libya. Libyan J Med. 2012;7:18556. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v7i0.18556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry-Is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zipkin DA, Steinman MA. Interactions between pharmaceutical representatives and doctors in training. A thematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:777–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balhara YP, Mathur S, Anand N. A study of attitude and knowledge of the psychiatry resident doctors toward clinician-pharmaceutical industry interaction. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:61–5. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.96162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma SK. Physician pharmaceutical industry interaction: Changing dimensions and ethics. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee C, Srinivasan V. Ethical issues in health care sector in India. IIMB Manage Rev. 2013;25:49–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatt A. A new challenge for Indian physicians and healthcare industry: Decoding the MCI code of professional conduct. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:1–2. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.62415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt AD. Drug promotion and doctor: A relationship under change? J Postgrad Med. 1993;39:120–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bal A. Can the medical profession and the pharmaceutical industry work ethically for better health care? Indian J Med Ethics. 2004;1:17. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2004.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy N. Who rules the great Indian drug bazaar? Indian J Med Ethics. 2004;1:2–3. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2004.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anand AC. The pharmaceutical industry: Our ‘silent’ partner in the practice of medicine. Natl Med J India. 2000;13:319–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalantri SP. Drug industry and medical conferences. Indian J Anaesth. 2004;48:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz D, Caplan AL, Merz JF. All gifts large and small: Toward an understanding of the ethics of pharmaceutical industry gift-giving. Am J Bioeth. 2003;3:39–46. doi: 10.1162/15265160360706552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grande D. Limiting the influence of pharmaceutical industry gifts on physicians: Self-regulation or government intervention? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:79–83. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1016-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green MJ, Masters R, James B, Simmons B, Lehman E. Do gifts from the pharmaceutical industry affect trust in physicians? Fam Med. 2012;44:325–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chew LD, O’Young TS, Hazlet TK, Bradley KA, Maynard C, Lessler DS. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians’ behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:478–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alssageer MA, Kowalski SR. What do Libyan doctors perceive as the benefits, ethical issues and influences of their interactions with pharmaceutical company representatives? Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:132. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.14.132.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alssageer MA, Kowalski SR. Doctors’ opinions of information provided by Libyan pharmaceutical company representatives. Libyan J Med. 2012:7. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v7i0.19708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Othman N, Vitry AI, Roughead EE, Ismail SB, Omar K. Medicines information provided by pharmaceutical representatives: A comparative study in Australia and Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:743. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chressanthis GA, Khedkar P, Jain N, Poddar P, Seiders MG. Can access limits on sales representatives to physicians affect clinical prescription decisions? A study of recent events with diabetes and lipid drugs. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14:435–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lieb K, Brandtönies S. A survey of German physicians in private practice about contacts with pharmaceutical sales representatives. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:392–8. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieb K, Scheurich A. Contact between doctors and the pharmaceutical industry, their perceptions, and the effects on prescribing habits. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]