Abstract

Objective:

This study aims to describe the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) profile of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) population attending outpatient clinics in Sargodha City, Pakistan.

Methods:

The study was designed as a cross-sectional descriptive survey. T2DM patients attending a tertiary care institute in Sargodha, Pakistan were targeted for the study. The EuroQol EQ-5D was used for the assessment of HRQoL and was scored using values derived from the UK general population survey. Descriptive statistics were used for the elaboration of sociodemographic characteristics. The Chi-square test was used to depict the possible association between study variables and HRQoL. Where significant associations were noted, Phi/Cramer's V was used for data interpretation accordingly. SPSS version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis and P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results:

Three hundred and ninety-two patients were approached for the study. The cohort was dominated by males (n = 222, 56.60%) with 5.58 ± 4.09 years of history of T2DM. The study highlighted poor HRQoL among the study participants (0.471 ± 0.336). Gender, marital status, education, monthly income, occupation, location and duration of the disease were reported to be significantly associated with HRQoL (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

T2DM imposes a negative effect on HRQoL of the patients. Attention is needed to highlight determinants of HRQoL and to implement policies for better management of T2DM, particularly in early treatment phases where improving HRQoL is still possible.

KEY WORDS: EQ-5D, health-related quality of life, Pakistan, type 2 diabetes mellitus

Health related Quality of life (HRQoL) is defined as a person's perceived quality of life representing satisfaction in the areas likely to be affected by health status.[1] The assessment of HRQoL is important as it identifies health-related needs of a particular population and delivers quality care especially in populations with chronic diseases.[2] Although because of the nature of chronic diseases, a decrease in HRQoL is expected,[3] improvement in HRQoL not only benefits the patients but also reduces social, financial and psychological burden related to chronic diseases.[4] Therefore, for the past few decades, HRQoL is shaping as an important assessment variable in designing and developing pharmaceutical care plans.

In line to what is reported earlier, chronic degenerative diseases are reported to impose a negative impact on HRQoL. Chronic diseases are the major cause of mortality and disability, accounting for 59% of annual deaths around the globe.[5] Within this context, Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a serious public health concern because of its heavy financial and social cost involved in the management process.[6] T2DM demands a lifetime of careful behavior and personal care as it is a disease with serious short and long-term consequences for the afflicted.[6] Both micro and macro-vascular complications are associated with T2DM and the risk of death from a cardiac or cerebrovascular event is also significantly elevated when compared with people without T2DM.[7,8,9] Several studies have shown that at 1-year postmyocardial infarction (MI), 41% of diabetics patients were at high risk of mortality; that is 2-fold when compared with nondiabetics. At 5 years postMI, mortality can be 72% higher than that of nondiabetics.[10] In addition to the diabetes-related complications, episodes and fear of hypoglycemia, change in lifestyle and fear of long-term consequences develop a state of anxiety among T2DM patients which leads to reduced HRQoL.[11,12] Moreover, the HRQoL profile decreases with disease progression and complications.[13,14] In the presence of co-morbidities or multiple diabetes-related complications, HRQoL deteriorates further, hence producing a mental, societal and financial burden on patients, caregivers and the healthcare system.[13]

Shifting our concerns toward HRQoL in developing countries, the very concept is often neglected when patients are treated for chronic diseases. Within this context, Pakistan being one of the highest populated countries in the world has more than 24% of the population living below the national poverty line.[15] In addition, the lacks of healthcare facilities, as well as the human resource, are a major obstacle in the delivery of optimal healthcare to facilitate the population. In the presence of these entities, the healthcare is unable to provide the “required” facilities and in turn affects the health status of the patients. Information of HRQoL in general and the impact of T2DM in particular on patient's physical, mental and social well-being have not yet been reported in Pakistan. Therefore, the present study is aimed to assess the HRQoL of patients with T2DM in Pakistan.

Methods

Study design, settings and recruitment of subjects

A questionnaire-based cross-sectional survey was carried out to assess the HRQoL of T2DM patients attending outpatient clinics of a tertiary care hospital in Sargodha, Pakistan. The institute is a teaching hospital in nature and provides diagnostic and treatment facilities to the poor and middle-income classes. A prevalence-based approach was sued to identify the required sample for this study. As T2DM is reported to affect 12% of the population in Pakistan,[16] therefore, 392 patients were recruited for the study.[17]

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adult patients aging 30 years and above, with a confirmed diagnosis of T2DM and ability to read and write Urdu (the official language of Pakistan) were included in the study. Pregnant women, patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus, having severe diabetic complications, psychiatric disorders, and immigrants from other countries were excluded from this study.

Ethical considerations

To date, there is no ethical requirement for nonclinical observational studies in Pakistan.[18] However, permission from the respective medical superintendent of the hospital was taken to conduct the study (approval number: DHSGD-2905/2014). Prior to data collection, patients who agreed to participate were explained nature and the objectives of the study and were assured of the confidentiality of the information. Written consent was also taken from the patients prior to data collection.

Data abstraction

HRQoL in patients with T2DM was measured by using a EuroQol EQ-5D scale. It is a frequently used generic HRQoL instrument and provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status.[19] The EQ-5D includes a visual analogue scale (VAS), which records the respondent's self-rated health status on a graduated (0–100) scale, the best imaginable health state (score of 100) and the worst imaginable health state (score of 0), with higher scores for higher HRQoL. This information can be used as a quantitative measure of health outcome as judged by the individual respondents. It also includes the EQ-5D descriptive system, which comprises five dimensions of health: Mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, each of which can take one of three responses. The response records three levels of severity (no problems/some or moderate problems/extreme problems) within a particular EQ-5D dimension.[20] EQ-5D is applicable to a wide range of health index values for health status. The Urdu (national language of Pakistan) version of EQ-5D was provided by EuroQol upon request, and the study was also registered with EuroQol.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sociodemographic variables of the participants. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as percentages and frequencies. The characteristics of the whole sample were presented. The Pearson Chi-square test was performed to test the statistical significance among the variables, and P < 0.05 was considered as significant. The EQ-5D preference weight for each health state was not available for Pakistani population. Therefore, these were derived from the TTO tariff of preference weights of the UK general population.[15] The collected data were analyzed by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 Software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient's demographics

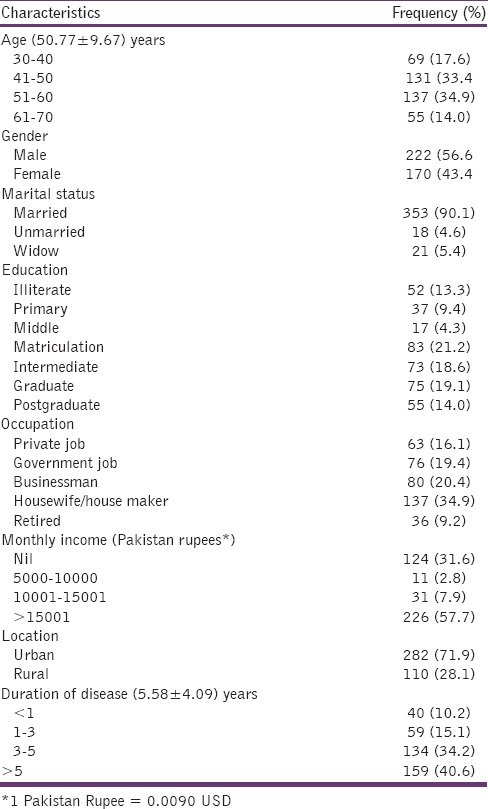

Three hundred and ninety-two T2DM patients were included in the study. The description of sociodemographic variables and frequency distribution of the respondents are summarized in Table 1. The mean age (SD) of the patients was 50.77 (9.67) years, with 56.6% males dominated the cohort. Three hundred and fifty-three (90%) of the respondents were married with mean (SD) duration of disease was 5.58 (4.09) years. Eighty-three (21%) had matriculation level of education with 137 (34.9%) were housewives/house makers. Two hundred and twenty-six (58%) had a monthly income of more than Pakistan rupees 15,000/month with 282 (71.9%) had urban residencies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents (n=392)

EQ-5D health status

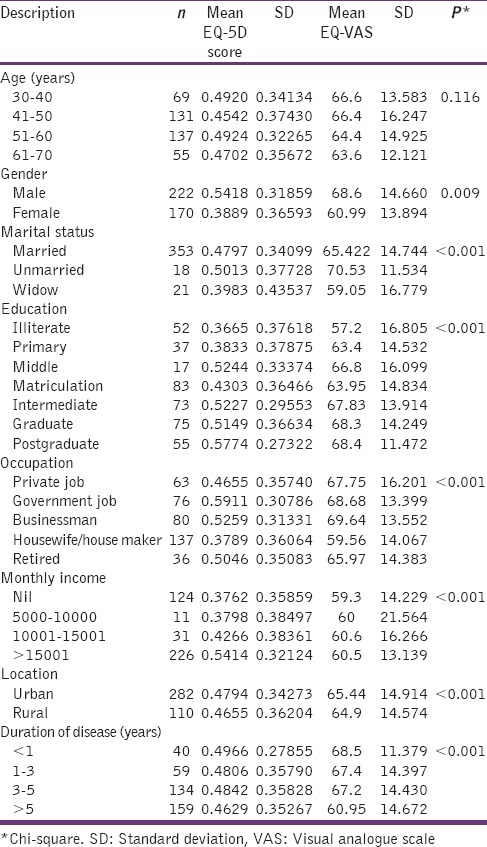

The HRQoL scores of patients are outlined in Table 2. The mean EQ-5D descriptive score was 0.4715 ± 0.3360 and EQ-VAS score was 64.77 ± 6.566. Table 2 presents the relationship analysis between health states and HRQoL scores.

Table 2.

Description of health-related quality of life scores

Statistically significant differences were reported when gender, marital status, education, monthly income, occupation, location, and duration of disease were kept into consideration (P < 0.001). The interpretation of analysis further reported that among the educational variable, the illiterate group had a strong relationship with respect to other educational classes (ϕc = 0.494). Furthermore, with respect to gender, males were more in agreement as compared with their counterparts (ϕc = 0.569). Association among other significant values was too low to produce an inference on the statistics.

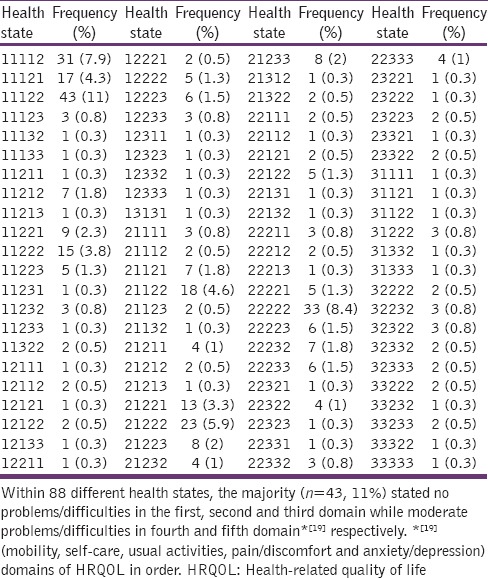

Eighty-eight different EQ-5D health states were described by the patients. The majority of the participants (n = 43, 11%) pointed out no problems/difficulties in the first, second and third domain while moderate problems/difficulties in the fourth and fifth domain. There was not a single patient who stated no problem in all five domains and one participant who described severe problems/difficulties in all domains as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequency of self-reported (EQ-5D) health states

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine the impact of T2DM on the HRQoL. Individuals with T2DM reported reduced HRQoL. Our findings are in line to the studies whereby HRQoL decreased with disease progression and complications.[12,21] Another study of same nature revealed that diabetic patients with poor metabolic control reported more retinopathy, vascular, and nervous problems.[22] Furthermore, the present study concluded that HRQoL had a statistically significant relationship with gender, income, education, location, and duration of disease. Quah et al. reported that higher HRQoL in diabetic patients is associated with young age, male gender, and a higher education level.[23] Similarly, Woodcock et al. and Gulliford and Mahabir reported that patients having diabetes for more than 5 years had lower scores in all domains except in blood pressure.[24,25] In addition, obesity and educational level were also associated with lower levels of HRQoL.[26,27] Therefore, in the light of the literature, previous studies do support and supplement the present findings.

Within the context of a developing country like Pakistan, data on HRQoL is limited, and there is scarcity of information. To the best of our knowledge, only one study reported the HRQoL profile of diabetic patients in Pakistan, but from a different healthcare setting. Even though, the instrument used for HRQoL assessment was different to the present study, the authors reported a decreased HRQoL among patients with T2DM.[28] In addition, a decreased HRQoL was reported by patients of other chronic diseases from various areas of Pakistan which further augments that chronic diseases have a negative impact of the HRQoL of the patients.[29,30,31]

HRQoL is a multidimensional construct referring to an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.[32] The developing countries are facing a number of challenges in providing optimal health care to all of its population. Within this context, Pakistan is a South-Asian country with a population of approximately 150 million (69% of the population are rural, spread over an area of 8,00,000 km2). Pakistan was ranked among the top 10 countries of the world with the highest number of people with diabetes in 2004, and an estimated 14.5 million Pakistanis will have diabetes by the year 2025.[16] In Pakistan, health services are very expensive, and the majority of health care cost is paid by patients themselves. Resource constraints society, lack of medical facilities and insufficient allocation of health budget are barriers to quality care. Most often the patient is unable to afford the high cost of treatment.[33,34] In return, a large number of patients tend to move to other healthcare providers such as Homeopaths and Hakeems (Unani-Tib) prior to consulting certified practitioners. The prevalence of such factors affects the HRQoL to an extent more than it is believed to be; hence, increase in the cost of therapy affects the HRQoL.[15] Institutions specializing in diabetes care are limited in number and are concentrated in the big cities only. Family physicians have little time (the average time spent with a person with diabetes was 8.5 min) for counseling.[35] The landscape of public health service delivery presents an uneven distribution of resources between rural and urban areas. The rural poor are at a clear disadvantage in terms of primary and tertiary health services, and also fail to benefit fully from public programs. The poor state of public facilities overall has contributed to the diminished role of public health facilities while the private sector's role in the provision of service delivery has increased enormously. Following the 18th amendment to the constitution in Pakistan, the health sector has been devolved to the provinces, but the distribution of responsibilities and sources of revenue generation between the tiers remains unclear.[36]

Conclusion

This study was conducted to evaluate the HRQoL of individuals with T2DM attending outpatient clinics in Sargodha City, Pakistan. The findings concluded that T2DM has a negative effect on HRQoL. The study also confirmed that T2DM remains a critical predictor of health outcomes among patients. Results from this study could be useful in clinical practice, particularly in the early treatment of T2DM patients where improving HRQoL is still possible. The present data could be used in developing a blueprint for educational sessions for T2DM patients in Pakistan.

Limitations

The study was conducted with a small number of T2DM patients who were selected from the outpatient clinic of public sector teaching (tertiary care) hospital situated in Sargodha, Pakistan and hence, the study findings might not be able to generalize to the entire T2DM population of the country.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the patients for participating in the study and the staff at the teaching hospital for their support in conducting the study.

References

- 1.Peterson SJ, Bredow TS. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. Middle Range Theories: Application to Nursing Research. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannucci E, Bardini G, Ricca V, Rotella C. Predictors of diabetes-related quality of life. Diabetologia. 1997;40:A640. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torrance GW. Utility approach to measuring health-related quality of life. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:593–603. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Globe D, Young NL, Von Mackensen S, Bullinger M, Wasserman J. Healthrelated Quality of Life Expert Working Group of the International Prophylaxis Study Group. Measuring patient-reported outcomes in haemophilia clinical research. Haemophilia. 2009;15:843–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Commission. Diabetes. 2015. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.ec.europa.eu/health/major_chronic_diseases/diseases/diabetes/index_en.htm .

- 7.Gilbert RE, Tsalamandris C, Bach LA, Panagiotopoulos S, O’Brien RC, Allen TJ, et al. Long-term glycemic control and the rate of progression of early diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1993;44:855–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, Chait A, Eckel RH, Howard BV, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1999;100:1134–46. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Cruickshanks KJ. Relationship of hyperglycemia to the long-term incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karlson BW, Herlitz J, Hjalmarson A. Prognosis of acute myocardial infarction in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 1993;10:449–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1993.tb00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grandy S, Fox KM. SHIELD Study Group. Change in health status (EQ-5D) over 5 years among individuals with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus in the SHIELD longitudinal study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:99. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes J, McGill S, Kind P, Bottomley J, Gillam S, Murphy M. Health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetes (TARDIS-2) Value Health. 2000;3(Suppl 1):47–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2000.36028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peyrot M, Rubin RR. Levels and risks of depression and anxiety symptomatology among diabetic adults. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:585–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Wittenberg E, Bosch JL, Cagliero E, Delahanty L, et al. Correlates of health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1489–97. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ul Haq N, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Saleem F, Aljadhey H. A cross sectional assessment of health related quality of life among patients with Hepatitis-B in Pakistan. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:91. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shera AS, Rafique G, Khwaja IA, Ara J, Baqai S, King H. Pakistan national diabetes survey: Prevalence of glucose intolerance and associated factors in Shikarpur, Sindh Province. Diabet Med. 1995;12:1116–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1995.tb00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniel WW. 7th ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1999. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Bioethics Committee Pakistan. Ethical Research Committee-Guidelines. 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 11]. Available from: http://www.pmrc.org.pk/erc_guidelines.htm .

- 19.EuroQol Group. EuroQol – A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: Development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care. 2005;43:203–20. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Wrobel JS, Vileikyte L. Quality of life in healing diabetic wounds: Does the end justify the means? J Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;47:278–82. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson D, Lager I, Nilsson PM. Socio-economic characteristics and quality of life in diabetes mellitus – Relation to metabolic control. Scand J Public Health. 1999;27:101–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quah JH, Luo N, Ng WY, How CH, Tay EG. Health-related quality of life is associated with diabetic complications, but not with short-term diabetic control in primary care. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2011;40:276–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulliford MC, Mahabir D. Relationship of health-related quality of life to symptom severity in diabetes mellitus: A study in Trinidad and Tobago. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:773–80. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woodcock AJ, Julious SA, Kinmonth AL, Campbell MJ. Diabetes Care From Diagnosis Group. Problems with the performance of the SF-36 among people with type 2 diabetes in general practice. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:661–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1013837709224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redekop WK, Koopmanschap MA, Stolk RP, Rutten GE, Wolffenbuttel BH, Niessen LW. Health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in Dutch patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:458–63. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schweikert B, Hunger M, Meisinger C, König HH, Gapp O, Holle R. Quality of life several years after myocardial infarction: Comparing the MONICA/KORA registry to the general population. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:436–43. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riaz M, Rehman RA, Hakeem R, Shaheen F. Health related quality of life in patients with diabetes using SF-12 questionnaire. J Diabetol. 2013;2:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaudhry Z, Siddiqui S. Health related quality of life assessment in Pakistani paediatric cancer patients using PedsQL™ 4.0 generic core scale and PedsQL™ cancer module. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:52. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saleem F, Hassali MA, Shafie AA. A cross-sectional assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among hypertensive patients in Pakistan. Health Expect. 2014;17:388–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarwar AM, Waqas M, Mumtaz A, Aslam MA. Status of health related quality of life between HBV and HCV patients of Pakistan. IntJ Bus Soc Sci. 2011;2:213–20. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of the Assessment: Field Trial Version. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Govender VM, Ghaffar A, Nishtar S. Measuring the economic and social consequences of CVDs and diabetes in India and Pakistan. Biosci Trends. 2007;1:121–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khuwaja AK, Khowaja LA, Cosgrove P. The economic costs of diabetes in developing countries: Some concerns and recommendations. Diabetologia. 2010;53:389–90. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1581-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shera AS, Jawad F, Basit A. Diabetes related knowledge, attitude and practices of family physicians in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:465–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency. Understanding Punjab Health Budget 2012-2013 Lahore, Pakistan. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 12]. Available from: http://www.pildat.org/publications/publication/budget/UnderstandingPunjabHealthBudget2012-2013-ABriefforPAPStandingCommitteeonHealth.pdf .