Abstract

Background:

Tetracycline is one of the most frequently used antibiotics in Nigeria both for human and animal infections because of its cheapness and ready availability. The use of tetracycline in animal husbandry could lead to horizontal transfer of tet genes from poultry to human through the gut microbiota, especially enterococci. Therefore, this study is designed to identify different enterococcal species from poultry feces in selected farms in Ilishan, Ogun State, Nigeria, determine the prevalence of tetracycline resistance/genes and presence of IS256 in enterococcal strains.

Materials and Methods:

Enterococci strains were isolated from 100 fresh chicken fecal samples collected from seven local poultry farms in Ilishan, Ogun State, Nigeria. The strains were identified by partial sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. Antibiotic susceptibility of the isolates to vancomycin, erythromycin, tetracycline, gentamicin, amoxycillin/claulanate, and of loxacin were performed by disc diffusion method. Detection of tet, erm, and van genes and IS256 insertion element were done by polymerase chain reaction amplification.

Results:

Sixty enterococci spp. were identified comprising of Enterococcus faecalis 33 (55%), Enterococcus casseliflavus 21 (35%), and Enterococcus gallinarium 6 (10%). All the isolates were resistant to erythromycin (100%), followed by tetracycline (81.67%), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (73.33%), ofloxacin (68.33%), vancomycin (65%), and gentamicin (20%). None of the enterococcal spp. harbored the van and erm genes while tet(M) was detected among 23% isolates and is distributed mostly among E. casseliflavus. IS256 elements were detected only in 33% of E. casseliflavus that were also positive for tet(M) gene.

Conclusion:

This study provides evidence that tetracycline resistance gene is present in the studied poultry farms in Ilishan, Ogun State, Nigeria and underscores the need for strict regulation on tetracycline usage in poultry farming in the studied location and consequently Nigeria.

KEY WORDS: Enterococci, poultry, resistance, tet(M)

Uncontrolled use of antibiotics in Nigeria poultry production poses serious public health concerns with respect to spread and selection of antibiotic resistant foodborne bacteria and genes. Food processing animals especially poultry serving as reservoirs for antimicrobial resistant bacteria is of greater concern due to their potential ability in the spread of resistant genes among human normal flora.[1,2] The use of antibiotics in livestock management has been reported as one of the factors responsible for the development of resistant bacteria and dissemination from livestock strains to human.[3] This is because antimicrobials used in the treatments of infected animals are in most cases of the same class of antimicrobials as those used in human medicine and may co-select for antimicrobial resistance in bacteria such as, enterococci during consumption of animal food.[3,4] Apart from being one of the primary causes of nosocomial infection, enterococci are also known as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance genes.[5,6] Enterococci as part of human gastrointestinal flora are capable of both receiving and transferring of resistance genes from other commensals as well as pathogenic bacteria domiciled in the gastrointestinal tract.

Tetracyclines are class of antimicrobial agents that are frequently used in poultry because of their broad-spectrum of activities and affordability in terms of cost.[7] Extensive uses of tetracyclines have often led to an emergence of resistant bacteria.[7] As a mechanism of action, they enter the bacterial cell and prevent the association of aminoacyl-tRNA by binding to bacterial ribosomes, thereby weakening the ribosome-tRNA interaction and stopping the protein synthesis.[8] The most commonly encountered tetracycline resistant determinant in enterococci is tet(M) and is commonly associated with conjugative transposon particularly Tn916[9,10,11] although it has also been reportedly found on plasmids.[12,13] IS256 was initially described as the flanking region of the composite aminoglycoside resistance mediating transposon Tn4001. However, the element also occurs in multiple, independent copies in the genomes of staphylococci and enterococci.[14] There have been reports of resistance to certain antibiotics including tetracycline by enterococci, which has also been attributed to extensive antibiotics use in veterinary medicine.[15,16,17] According to Bonafede et al.,[18] certain mobile genetic elements such as IS256 are involved in transfer of resistant genes in enterococci.

Tetracyclines are frequently used in Nigeria for livestock management[19] hence the investigation on the prevalence of tetracycline resistant genes in human and animals in relation to commensal organisms remains an important research interest. Data regarding the occurrence and dissemination of tetracycline resistance genes and IS256 in enterococci from poultry in Nigeria are scarce; hence, this study was designed to investigate the prevalence of tet genes and IS256 element associated with commonly prescribed antibiotics (tetracycline) in enterococcal infection among poultry isolates of enterococci from Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and presumptive identification of enterococci

Enterococci spp. were isolated according to a previous method[20] with modifications. Briefly, a hundred fresh chicken fecal samples were collected from 7 local poultry farms in the Ilishan, Ogun State, Nigeria. One gram of each fecal sample was diluted 1:10 phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) vortex, and 100 μl of the solution was inoculated onto bile esculin agar (Oxoid) which was incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h. Presumptive enterococcal isolates with dark brown colonies and morphologically resembling enterococci were selected for further identification.

Identification by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene

The DNA was extracted by QuickExtract™ DNA extraction solution (Epicenter, Wisconsin) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted DNA was then used as a template in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification with primers BSF8N 5’-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3’, BSR534 5’-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC-3’ in a 20 µl reaction consisting of 10 µl Master mix (RedTag, Sigma, Aldrich), 2 µl primers, 1 µl DNA, and 7 µl distilled water. The PCR conditions are 10 min of initial denaturation at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of annealing of 15s at 95°C, 30s at 55°C, and 30s at 72°C, followed by a single 7 min extension at 72°C and finally set on hold at 4°C. The PCR products are analyzed on 1% agarose gel in TAE buffer containing GelRed, run at approximately 40 m amp for 45 min and visualized under ultraviolet (UV) light. The PCR products were purified and sequenced using standard procedures. The basic local alignment search tool program was used to compare the identity of the sequences obtained with those held in GenBank database.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid, UK), according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Guidelines,[21] antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) was performed for vancomycin (30 µg), erythromycin (30 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), amoxycillin/claulanate (30 µg), and ofloxacin (5 µg). Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 and ATCC 51299 were used for quality control.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification of resistance genes

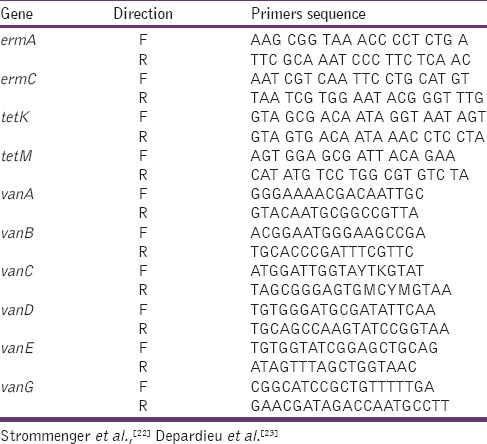

All the isolates resistant to tetracycline, erythromycin, and vancomycin were further investigated for the amplification of tet, erm, and van genes, respectively. The bacterial DNA was extracted by QuickExtract™ DNA extraction solution (Epicenter, Wisconsin) PCR amplification was carried out using previously published primers [Table 1],[22,23] in a total volume of 20 µl containing 1 µl DNA templates 10 µl Master mix (RedTag, Sigma, Aldrich), 2 µl primers and 7 µl distilled water ermA, ermC, tetK, and tetM were amplified according to previously described method[22] while vanA, vanB, vanC, vanD, vanE, and vanG genes were amplified in a multiplex PCR according to the method described by Depardieu et al.[23] Some bacterial strains in our lab collection were used as positive control.

Table 1.

List of resistant genes primer used

To establish whether IS256 elements were present in resistant isolates, PCR amplification of a 468 bp fragment specific to IS256 was also performed with IS256 primer F 5’-TGAAAAGCGAAGAGATTCAAAGC-3’ and R 5’-ATGTAGGTCCATAAGAACGGC-3’ with PCR conditions at 95°C for 5 min, 25 cycles of 94 for 30 s, 52 for 30 s, 72 for 1 min and 72 for 10 min.

All amplicons were analyzed by loading 6 µl on 1.5% agarose gel, stained with GelRed and visualized under UV light.

Results

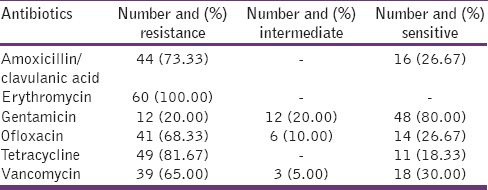

Of the 100 samples analyzed, 60 enterococcal spp. comprising of E. faecalis 33 (55%), Enterococcus casseliflavus 21 (35%), and Enterococcus gallinarium 6 (10%) were recovered. Bacteria not in this category that were isolated along were not considered for further assay. Table 2 shows the results of the AST of the isolated Enterococcus spp. All the isolates were resistant to erythromycin followed by tetracycline 81.67% (49/60), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 73.33% (44/60), ofloxacin 68.33% (41/60), vancomycin 65% (39/60), and gentamicin 20% (12/60).

Table 2.

Antibiotic resistance pattern of enterococcal strains

Detection of resistance genes

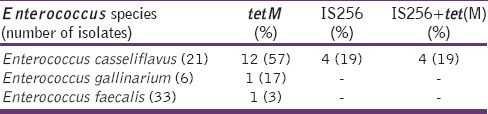

Detection of resistance genes and distribution among the 60 enterococci is summarized in Table 3. None of the enterococal spp. that were phenotypically resistant to vancomycin and erythromycin harbored the van and erm genes. Of the two tet resistance genes investigated, only tet(M) was amplified in 14 (23%) isolates and was distributed among E. casseliflavus (12/86%), Enterococcus gallinarium (1/7%), and E. faecalis (1/7%). Fifty-seven percentage of isolated E. casseliflavus carry the tet(M) gene. IS256 was detected in only 4 isolates of E. casseliflavus that were also positive for tet(M) gene [Table 3 and Figure 1].

Table 3.

Distribution of tetM gene and IS256 sequence among enterococci from chicken

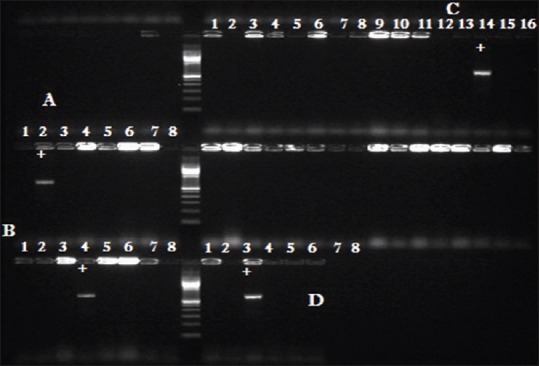

Figure 1.

PCR amplification of Four IS256 element gene on 1.5% agarose gel. Pix A to D showing positive amplicons respectively

Discussion

Monitoring of resistance to antibiotics among commensal bacteria is not only important in human population but also among animals in order to detect the possible transference of resistant bacteria or genes of animal origin to humans. Resistance to antimicrobials in enterococci from poultry has been found throughout the world and is generally recognized as associated with antimicrobial use.[16]

In the present study, species distribution of isolates shows that E. faecalis dominated the isolated enterococci spp. with 55% population followed by E. casseliflavus 35%, and E. gallinarium 10%. This is in agreement with a previous study that reported the dominance of E. faecalis from poultry source[24] but in contrast to many previous studies, E. casseliflavus was more prominent among the isolates while E. faecium was not isolated in this study. The reason for the low prevalence of E. faecium in this study remains unclear. More than 60% multidrug resistance was observed among the isolates to erythromycin, tetracycline, vancomycin, ofloxacin, or amoxicillin/clavulanate antibiotics commonly prescribed as therapeutic agents for human use as well as animals.

All the isolates were resistant to erythromycin while more than 80% were resistant to tetracycline and 65% resistant to vancomycin. In line with previous studies reporting prevalence of tet(M) among enterococci,[9,24,25] results of the present study have also shown the presence of tet(M) gene encoding tetracycline resistance and were detected in 23.33% of the total isolates in this study. Among enterococci species, tet(M) is the most frequently encountered tetracycline-resistance gene and is most commonly located in the bacterial chromosome and has been found to be associated with conjugative transposons related to the Tn916/Tn1545 family.[25,26] Despite the high resistance to erythromycin and vancomycin among the isolates in this study, none of the studied isolates amplified the various erm and van genes investigated by PCR assay. This suggests interplay of additional mechanisms of resistance to these drugs that are not investigated in this study. Although evidence have established that erythromycin and vancomycin resistance could be associated with transposon elements that are usually flanked by insertion sequence (IS) elements,[11,25,26,27] in this study, IS256 was detected among tet(M) positive species of E. casseliflavus (n = 4) suggesting the presence of transposable elements usually flanked by two copies of IS256 among the isolates. Rice and Carias[28] emphasized the important roles played by insertion elements in evolution of antimicrobial resistance in Gram-positive bacteria. According to McAshan et al.,[29] IS elements are capable of influencing avirulent commensal species of bacteria to a nosocomial pathogenic species. This is achievable by genomic arrangement often brought about by series of event attributed to IS elements. Although this study did not carry out an investigation on the presence of the commonly encountered transposons such as Tn916/Tn1545 and other related ones, we have reasons to assume the presence of IS256 among the isolates can be directly linked to their resistance profiles. This is because IS element within the IS256 family often form composite transposons.[30,31] There was an observed higher susceptibility (80%) to gentamicin among the isolates suggesting low frequency or absence of widespread Tn5281 (which is identical to Tn4001 in Staphylococcus) that harbors resistance to aminoglycosides among the isolates.

Conclusion

Our study shows a high-level phenotypic resistance to various antibiotics tested, particularly tetracycline, as well as the detection of tet(M) genes which are believed to be disseminated via IS256 element in some enterococci strains. The presence of tet(M) which is believed to be associated with IS256 in this study is of great concern since this could serve as a platform for easy dissemination of resistance genes via horizontal transfer or genetic mechanisms. Interestingly, the majority of the detected tet(M) gene and all the IS256 elements were found in E. casseliflavus. Apart from high probability of horizontal transfer of resistance among these species in poultry, these IS elements may also facilitate genomic relocations among these species. An event which may not only affect gene expression but may also increase the tendency of acquiring further adaptive mechanisms leading to the development of pathogenicity among avirulent commensals. Although a lot of attention has not been paid to this particular species in recent times regarding dissemination of resistance genes and pathogenicity, from our indications E. casseliflavus should be closely monitored and be screened further for their role in dissemination of resistance genes. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first in Nigeria describing the dissemination of tet(M) associated with IS256 elements among multiple drug resistance enterococci from poultry source.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Diarrassouba F, Diarra MS, Bach S, Delaquis P, Pritchard J, Topp E, et al. Antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in commensal Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from commercial broiler chicken farms. J Food Prot. 2007;70:1316–27. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.6.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mena C, Rodrigues D, Silva J, Gibbs P, Teixeira P. Occurrence, identification, and characterization of Campylobacter species isolated from portuguese poultry samples collected from retail establishments. Poult Sci. 2008;87:187–90. doi: 10.3382/ps.2006-00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray BE. Diversity among multidrug-resistant enterococci. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:37–47. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guardabassi L, Schwarz S, Lloyd DH. Pet animals as reservoirs of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:321–32. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huycke MM, Sahm DF, Gilmore MS. Multiple-drug resistant enterococci: The nature of the problem and an agenda for the future. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:239–49. doi: 10.3201/eid0402.980211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray BE. The life and times of the Enterococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:46–65. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chopra I, Roberts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: Mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:232–60. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnappinger D, Hillen W. Tetracyclines: Antibiotic action, uptake, and resistance mechanisms. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:359–69. doi: 10.1007/s002030050339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cauwerts K, Decostere A, De Graef EM, Haesebrouck F, Pasmans F. High prevalence of tetracycline resistance in Enterococcus isolates from broilers carrying the erm(B) gene. Avian Pathol. 2007;36:395–9. doi: 10.1080/03079450701589167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.You Y, Hilpert M, Ward MJ. Detection of a common and persistent tet(L)-carrying plasmid in chicken-waste-impacted farm soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:3203–13. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07763-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hummel A, Holzapfel WH, Franz CM. Characterisation and transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from enterococci isolated from food. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2007;30:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agersø Y, Pedersen AG, Aarestrup FM. Identification of Tn5397-like and Tn916-like transposons and diversity of the tetracycline resistance gene tet(M) in enterococci from humans, pigs and poultry. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:832–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jurado-Rabadán S, de la Fuente R, Ruiz-Santa-Quiteria JA, Orden JA, de Vries LE, Agersø Y. Detection and linkage to mobile genetic elements of tetracycline resistance gene tet(M) in Escherichia coli isolates from pigs. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:155. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-10-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozitskaya S, Cho SH, Dietrich K, Marre R, Naber K, Ziebuhr W. The bacterial insertion sequence element IS256 occurs preferentially in nosocomial Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates: Association with biofilm formation and resistance to aminoglycosides. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1210–5. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.1210-1215.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauderdale TL, Shiau YR, Wang HY, Lai JF, Huang IW, Chen PC, et al. Effect of banning vancomycin analogue avoparcin on vancomycin-resistant enterococci in chicken farms in Taiwan. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:819–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obeng AS, Rickard H, Ndi O, Sexton M, Barton M. Comparison of antimicrobial resistance patterns in enterococci from intensive and free range chickens in Australia. Avian Pathol. 2013;42:45–54. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2012.757576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzavaras I, Siarkou VI, Zdragas A, Kotzamanidis C, Vafeas G, Bourtzi-Hatzopoulou E, et al. Diversity of vanA-type vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolated from broilers, poultry slaughterers and hospitalized humans in Greece. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1811–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonafede ME, Carias LL, Rice LB. Enterococcal transposon Tn5384: Evolution of a composite transposon through cointegration of enterococcal and staphylococcal plasmids. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1854–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adesokan HK, Akanbi IO, Akanbi IM, Obaweda RA. Pattern of antimicrobial usage in livestock animals in South-Western Nigeria: The need for alternative plans. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2015;82:E1–6. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v82i1.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson CR, Fedorka-Cray PJ, Barrett JB, Ladely SR. Effects of tylosin use on erythromycin resistance in enterococci isolated from swine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4205–10. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4205-4210.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2010. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 20th Informational Supplement. M100-S20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strommenger B, Kettlitz C, Werner G, Witte W. Multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of nine clinically relevant antibiotic resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4089–94. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4089-4094.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Depardieu F, Perichon B, Courvalin P. Detection of the van alphabet and identification of enterococci and staphylococci at the species level by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5857–60. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5857-5860.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Getachew YM, Hassan L, Zakaria Z, Saleha AA, Kamaruddin MI, Che Zalina MZ. Characterization of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus isolates from broilers in Selangor, Malaysia. Trop Biomed. 2009;26:280–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice LB. Tn916 family conjugative transposons and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1871–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts MC. Update on acquired tetracycline resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;245:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puopolo KM, Klinzing DC, Lin MP, Yesucevitz DL, Cieslewicz MJ. A composite transposon associated with erythromycin and clindamycin resistance in group B Streptococcus. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56 (Pt 7):947–55. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rice LB, Carias LL. Transfer of Tn5385, a composite, multiresistance chromosomal element from Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:714–21. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.714-721.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McAshan SK, Vergin KL, Giovannoni SJ, Thaler DS. Interspecies recombination between enterococci: Genetic and phenotypic diversity of vancomycin-resistant transconjugants. Microb Drug Resist. 1999;5:101–12. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1999.5.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hegstad K, Mikalsen T, Coque TM, Werner G, Sundsfjord A. Mobile genetic elements and their contribution to the emergence of antimicrobial resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:541–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quintiliani R, Jr, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1547, a composite transposon flanked by the IS16 and IS256-like elements, that confers vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4281. Gene. 1996;172:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]