Abstract

Background

Migraine, particularly chronic migraine (CM), is underdiagnosed and undertreated worldwide. Our objective was to develop and validate a self-administered tool (ID-CM) to identify migraine and CM.

Methods

ID-CM was developed in four stages. (1) Expert clinicians suggested candidate items from existing instruments and experience (Delphi Panel method). (2) Candidate items were reviewed by people with CM during cognitive debriefing interviews. (3) Items were administered to a Web panel of people with severe headache to assess psychometric properties and refine ID-CM. (4) Classification accuracy was assessed using an ICHD-3β gold-standard clinician diagnosis.

Results

Stages 1 and 2 identified 20 items selected for psychometric validation in stage 3 (n = 1562). The 12 psychometrically robust items from stage 3 underwent validity testing in stage 4. A scoring algorithm applied to four symptom items (moderate/severe pain intensity, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea) accurately classified most migraine cases among 111 people (sensitivity = 83.5%, specificity = 88.5%). Augmenting this algorithm with eight items assessing headache frequency, disability, medication use, and planning disruption correctly classified most CM cases (sensitivity = 80.6%, specificity = 88.6%).

Discussion

ID-CM is a simple yet accurate tool that correctly classifies most individuals with migraine and CM. Further testing in other settings will also be valuable.

Keywords: Chronic migraine, migraine, screening, case-finding, diagnosis, sensitivity, specificity, validation studies

Introduction

Migraine, especially chronic migraine (CM), remains underdiagnosed and undertreated worldwide (1–7), despite the substantial burden it imposes on individuals, their families, and society (1,8–12). Data from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study suggest that only 56% of respondents meeting the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition (ICHD-2) migraine criteria had ever received a migraine diagnosis from a health care professional (13–15). Among AMPP Study respondents meeting modified Silberstein-Lipton CM criteria, only 20% reported receiving a CM diagnosis from a health care professional (1).

New epidemiologic data emerging from the longitudinal Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study (16) illuminate the obstacles to effective care for CM. Only a fraction of the CM sample (13.6%) in CaMEO reported consulting a specialist (i.e. neurologist, headache specialist, pain specialist) for diagnosis and treatment of migraine (2). Even among people with CM who consulted a specialist, only 36% reported receiving a diagnosis of CM (2,16). Furthermore, only 4.5% of people with CM and significant headache-related disability (Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) grade ≥2) who were currently consulting a health care professional ultimately received a diagnosis of CM and were receiving minimally appropriate acute and preventive treatment (7).

One traditional approach for improving the detection of under-ascertained medical conditions involves the use of screening or case-finding tools (17). The term “screening” is traditionally applied to tools that are designed to detect conditions in the presymptomatic phase (e.g. Papanicolaou (Pap) smears are screening tools for cervical cancer). The term “case-finding” is applied to tools that identify conditions that are underdiagnosed despite symptoms (e.g. the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire is a case-finding tool for depression). Because CM detection occurs during the symptomatic phase, the most appropriate term is “case-finding tool.” The term “screening tool” is widely used and carries the important implication that people detected using this tool require further diagnostic assessment. For these reasons, we use the terms “screening” and “case-finding” interchangeably herein.

The objective of this research was to develop a reliable and valid case-finding tool for CM, applicable to people self-identified with severe headache. This tool, Identify Chronic Migraine (ID-CM), is intended to help clinicians identify patients likely to have migraine, and in particular, likely to have CM. Herein, a four-stage process was used to develop and validate ID-CM.

Methods

Overview

The ID-CM development process comprised four distinct stages. First, an international Delphi Panel (18) of expert clinicians and researchers selected candidate items from existing instruments and generated additional items for consideration (stage 1). In stage 2, cognitive debriefing interviews among people with CM were conducted to assess relevance and understanding of the Delphi item pool. The item pool that emerged from the Delphi Panel and cognitive debriefings was then fielded in a sample of people with headache recruited from the Research Now (Plano, TX) Internet panel, to evaluate the psychometric properties of the candidate items (stage 3). The ID-CM item pool emerging from stage 3 was administered to people with headache who were independently assessed by headache-expert physicians using semi-structured diagnostic computer-assisted telephone interviews (stage 4). Classification accuracy for ID-CM was compared with diagnoses independently assigned by clinical experts using a Semistructured Diagnostic Interview for Migraine (SSDI-M; Web Appendix 1).

Institutional review board approval was obtained for all stages of this study involving humans, with different ethics boards used for various stages, depending on investigator site requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participant consent language and compensation are available on request.

Stage 1: Delphi Panel

A bank of candidate items for inclusion in ID-CM was developed based on a review of existing instruments: ID Migraine (19), MIDAS (20), the six-item Headache Impact Test (21), and the American Migraine Study (AMS)/AMPP Diagnostic Module (9,22–24). These items were then reviewed by three clinical experts (DWD, RBL, AMB), and evaluated by eight expert-clinician panelists (SKA, WJB, AMB, H-CD, DWD, RBL, MBV, S-JW) through a modified Delphi approach consisting of two rounds of consensus development. The item bank was reduced, and response options and recall periods were modified based on expert feedback.

Stage 2: Cognitive debriefings

Endpoint Outcomes (Boston, MA) recruited a target of approximately 10 individuals with CM for qualitative interviews to test the item bank emerging from the Delphi Panel. These individuals had headache (tension-type and/or migraine) on ≥15 days per month for ≥3 months within the last six months, had ≥5 attacks fulfilling ICHD-2 (25) criteria for migraine without aura, and fulfilled criteria for migraine pain and associated symptoms on ≥8 days per month for ≥3 months.

Cognitive debriefing interviews determined whether the participants understood the instructions, whether the items were worded appropriately, and how the participants interpreted the items and response options. Two alternative response options for symptoms were considered: a five-point response scale (never, rarely, sometimes, very often, or always) and a four-point response scale (never, rarely, less than half the time, half the time or more). Full details on the cognitive debriefing interviews are available on request.

Stage 3: Psychometric validation

The item pool emerging from stage 2, along with a set of concurrent patient-reported outcome measures, was administered to a Web-based sample of people screened for severe headache. The sampling frame was drawn from individuals previously screened for headache in a Web-panel study, including the CaMEO Study (16), which was drawn from the same panel (Research Now). This target population was selected to facilitate oversampling of individuals with CM.

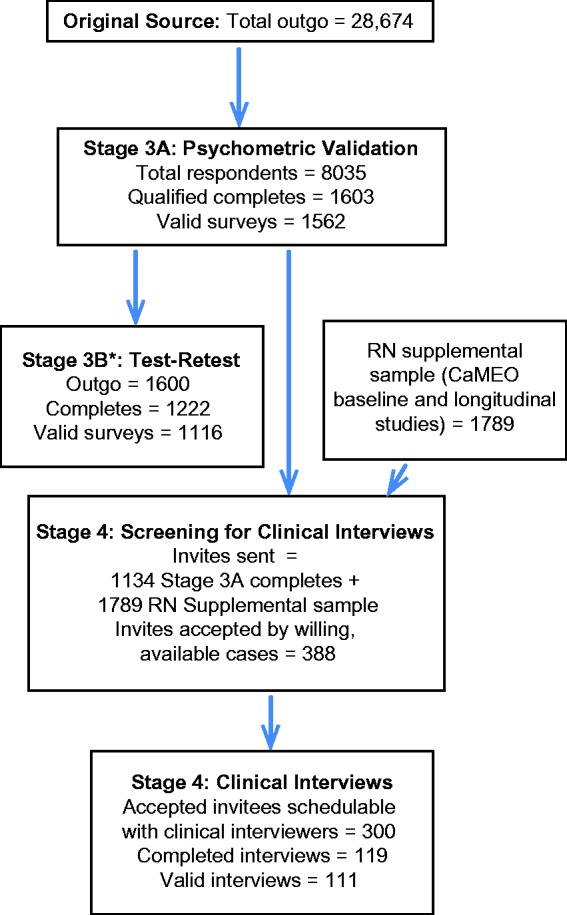

The target sample included 1600 total respondents, equally divided between migraine and other severe headache (Figure 1). The migraine group included people with episodic migraine (EM) and CM, based on the AMS/AMPP Diagnostic Module. People with nonmigraine severe headache were included to facilitate assessment of discriminative validity.

Figure 1.

Sampling flow.

CaMEO: Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes; RN: Research Now. *Stage 3 respondents were sent a second survey (Stage 3B) to assess test-retest reliability of the scale. Test-retest reliability and construct validity results will be presented in a forthcoming manuscript.

Study candidates were invited by email and screened to determine eligibility. Eligible participants were ≥18 years of age, provided an email address, were literate and conversant in English, and provided informed consent. Respondents were excluded from the study if they reported that all of their headaches were associated with cold, flu, head injury, or hangover.

Potentially eligible participants received the previously validated AMS/AMPP Diagnostic Module (22,23,26). People with severe headache and ≥15 headache days in the previous three months (average ≥5 headache days per month) were potentially eligible and classified as having migraine based on ICHD 3rd edition beta (3β) criteria and subclassified as EM or CM based on the modified Silberstein-Lipton criteria for CM (27,28). People with severe headache not meeting criteria for EM or CM were said to have nonmigrainous headache.

The modified Silberstein-Lipton CM criteria aligned to ICHD-3β criteria for CM in most respects; exceptions included the requirement that ≥8 of the headache days per month be linked to migraine (criterion C from the ICHD-3β CM criteria) and the exclusion of secondary headache disorders (both are difficult to address in survey research).

Data from these participants were used to conduct item calibration (the psychometric assessment of the quality of items in the measurement of a targeted domain). During calibration assessments, items exhibiting strong psychometric properties were retained and poorly performing items were eliminated.

Stage 4: Diagnostic validity

In this stage, the goal was to compare diagnoses assigned using ID-CM with independent “gold-standard” diagnoses assigned by headache experts using an SSDI-M. Clinicians were required to ask the questions as written, but were free to probe, based on clinical judgment, to obtain the most accurate information possible. This approach is often used to obtain gold-standard diagnoses for symptom-based conditions, including headache (29).

People with headache from the stage 3 validation sample or the CaMEO (16) longitudinal sample (both drawn from same panel) were invited to participate in the clinical interview. During the initial screening and scheduling process, participants provided their phone numbers. Study headache experts contacted participants by phone and directed them to an online survey link (containing ID-CM scale items). Participants completed the survey online and, when finished, received a four-digit confirmation code; this code also alerted the clinician that the survey had been completed. After ID-CM was complete, the clinician completed the SSDI-M and assigned a gold-standard diagnosis without access to ID-CM responses.

The SSDI-M was modified from an interview developed and used in epidemiologic research and clinical trials recruiting thousands of participants (30–32). The interview was extensively branched and based on the ICHD-3β migraine criteria and Silberstein-Lipton criteria for EM and CM. Interviews were conducted by eight headache physicians who had completed or were currently enrolled in an accredited headache fellowship. Physician interviewers were trained to administer the SSDI-M by reviewing written interviews, a training video, and participating in a webinar. They then conducted mock interviews and received feedback on their interviews from neurologists with expertise in these methods. Their diagnostic interviews were also audio recorded and reviewed randomly for quality. Diagnoses were assigned both by the clinician interviewer and using a computerized algorithm. If discrepancies occurred, the recorded interview was reviewed to arrive at a final diagnosis without access to ID-CM data.

Statistical analyses

Stage 1 (Delphi Panel) and stage 2 (cognitive debriefings)

Analyses in stage 1 involved descriptive summaries of the proportion of headache experts favoring candidate items. After the initial Delphi panelist endorsement of candidate items, panelists reviewed summarized responses from all panelists, and consensus was reached on the items to include in ID-CM. In stage 2, the cognitive debriefing data were summarized descriptively to identify any issues in the item wording and response options; problems with interpretation and relevance of items were also assessed. The Delphi Panel, cognitive debriefings, and related analyses (stages 1–2) were conducted by Endpoint Outcomes.

Stage 3: Psychometric validation

Details of the psychometric and statistical methods employed in stage 3 are provided in Web Appendix 2. Briefly, analyses for item calibration consisted of four steps: (1) examining the pattern of responses to determine the best distribution for modeling count items; (2) assessing the dimensionality of the item pool through generalized linear exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) for the mixed item distributions (count and multinomial), using oblique rotations for the factor solutions; (3) fitting multidimensional item response theory (IRT) models for the mixed item distributions (count and multinomial) based on the EFA factor structures; and (4) using a two-part modeling approach to predict ICHD-3β migraine and CM status from the IRT screener models. In each of the two-part models, structural equation models were estimated in which the latent factor for migraine severity predicted modified ICHD-3β status (vs other severe headache), and the CM severity latent factor predicted Silberstein-Lipton CM status (vs EM). Both models were based on the IRT measurement models. R2 estimates were used to characterize the proportion of variance explained in the observed classification by the latent factor defined on the screening items. Although high R2 values would not guarantee strong classification accuracy in stage 4, low R2 values would nearly guarantee poor classification accuracy in clinical interviews. Items determined to have performed poorly during item calibration were eliminated. Poor performance was defined as items that displayed factor loading and IRT parameter estimates consistent with weakly or poorly reliable items were eliminated. An additional pool of theoretically important items was brought forth from stage 3 into stage 4 and held in reserve in the event that additional information was needed to improve classification accuracy. Psychometric models were estimated using Mplus version 7.1 (33), and descriptive, graphic, and classification accuracy analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Stage 4: Diagnostic validity

Analyses employed for assessing classification accuracy used column and row percentages from 2-by-2 tables contrasting ID-CM classification with clinical interview diagnosis assignment to estimate sensitivity and specificity, and negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV), respectively. Analyses for stages 3 and 4 were conducted by author DS.

Results

Stage 1: Delphi Panel

The preliminary item pool consisted of 27 items assessing symptoms, headache days, activities of daily living, headache-related medication use, emotional reaction (“fed up”/“irritated” with headaches), concentration, work absence, work productivity, home productivity, and social activities. Twenty items were selected based on face validity and clinical judgment of the Delphi Panel.

Stage 2: Cognitive debriefings

Cognitive debriefing interviews were conducted with 13 individuals with CM. The draft items took an average of 3.8 minutes to complete. Overall, the items were well understood and considered relevant by participants; therefore, few revisions to the draft screening tool were considered. The emerging areas under consideration for revision included the use of a five- or four-category response scale and inclusion of an item about missed days of work/school. Participants indicated that they preferred both the five- and four-category response options equally; therefore, the four-category response option (never, rarely, less than half the time, or half the time or more) was retained for psychometric validation, to guard against diffusion in item responses, and the item about missed days of work/school was retained to capture headache-related disability. The items used in initial validation testing (stage 3) appear in Table 1.

Table 1.

Draft ID-CM items used in stage 3 validation testing.

| In the last three months (past 90 days) | In the past 90 days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. On how many days did you have a headache of any type? If a headache lasted more than one day, count each day. | _____ # of days | |||

| 2. On how many full days (from the time you woke up to the time you went to sleep) were you completely free of headache pain or discomfort? | _____ # of days | |||

| Please think about the past 30 days and describe the pain and other symptoms you have with your headaches. If you have more than one type of headache, please answer for your most severe type of headache. If you feel you can't answer an item, you may leave it blank. | ||||

| In the last month (past 30 days), when you have had headaches | Never | Rarely | Less than half the time | Half the time or more |

| 3. How often was the pain moderate or severe? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. How often was your headache pain aggravated by or caused avoidance of routine physical activity (e.g. walking or climbing stairs)? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. How often was the pain worse on just one side? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 6. How often was the pain pounding, pulsating or throbbing? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 7. How often did you experience neck pain? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 8. How often were you unusually sensitive to light (e.g. you felt more comfortable in a dark place)? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 9. How often were you unusually sensitive to sound (e.g. you felt more comfortable in a quiet place)? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 10. How often did you feel nauseated or sick to your stomach? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 11. How often did you feel fed up or irritated because of your headaches? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 12. How often did your headaches interfere with making plans? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 13. How often did you worry about making plans because of your headaches? | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| For the next question, if you don't remember the exact number, please give us the best answer you can. You may leave question 14 blank if you have not gone to work or school in the past 30 days. | ||||

| In the last month (past 30 days) | In the past 30 days | |||

| 14. On how many full days (from the time you woke up to the time you went to sleep) were you completely free of headache pain or discomfort? | _____ # of days | |||

| 15. On how many days did you have a headache of any type? | _____ # of days | |||

| 16. On how many days did you miss work or school because of your headaches? | _____ # of days | |||

| 17. On how many days did you not do household work because of your headaches? | _____ # of days | |||

| 18. On how many days did you miss family, social, or leisure activities because of your headaches? | _____ # of days | |||

| Please answer the next two questions about the medications you take only as needed to relieve your headaches. | ||||

| In the last month (past 30 days) | In the past 30 days | |||

| 19. On how many days did you use over-the-counter medications to treat your headache attacks? | _____ # of days | |||

| 20. On how many days did you use prescription medications to treat your headache attacks? | _____ # of days | |||

ID-CM: Identify Chronic Migraine.

Stage 3: Psychometric validation

Sampling returns

Data were collected between July 18 and 31, 2013. Figure 1 provides the sampling frame and completed surveys for this stage. Of the 28,674 individuals invited to participate in the online survey, 1562 (5.4%) participants met inclusion criteria and were eligible for analysis. Most participants were female (71.8%) and white (93.1%), with a mean (SD) age of 47.0 (15.0) years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of respondents in stages 3 and 4.

| Characteristic | Stage 3 (n = 1562) | Stage 4 (n = 111) |

|---|---|---|

| Women, n (%) | 1121 (71.8) | 92 (82.9) |

| Mean (SD) age, y | 47.0 (15.0) | 46.2 (13.4) |

| Age, years, n (%) | ||

| 18–29 | 245 (15.7) | 16 (14.4) |

| 30–39 | 276 (17.7) | 19 (17.1) |

| 40–49 | 324 (20.7) | 30 (27.0) |

| 50–59 | 370 (23.7) | 31 (27.9) |

| ≥60 | 347 (22.2) | 15 (13.5) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 1454 (93.1) | 99 (89.2) |

| Non-white | 108 (6.9) | 12 (10.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 1474 (94.4) | 101 (91.0) |

| Hispanic | 88 (5.6) | 10 (9.0) |

| Income, n (%) | ||

| <$30,000 | 338 (21.7) | 27 (24.3) |

| $30,000–$49,999 | 270 (17.3) | 20 (18.0) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 340 (21.8) | 28 (25.2) |

| ≥$75,000 | 610 (39.2) | 36 (32.4) |

Psychometric properties

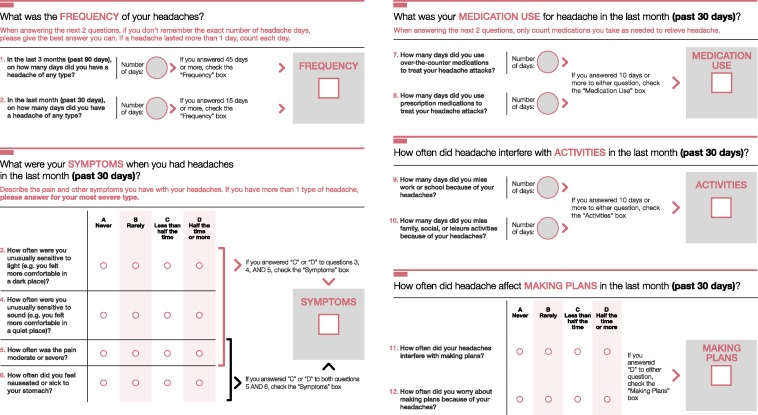

Several exploratory factor models were fit and rotated using a wide array of oblique rotation algorithms (Table 3). The negative binomial distribution was used to model all count items in the EFAs. The final EFA solution was based on an oblique quartimax rotation. This solution was composed of three factors characterizing symptoms, disability/planning disruption, and family disruption because of headache. Items related to medication-use days, headache frequency, and items assessing days of headache freedom contributed to model estimation failure because of a linear dependency and were eliminated from the analysis. As a result, these items were not included in the subsequent EFAs and IRT models. However, headache days and medication-use days were retained for stage 4 classification accuracy assessment because of clinical and theoretical importance. The item pool remaining after item calibration in a multifactor IRT model was composed of all three of the disability items, all three of the planning disruption items, and the remaining four symptom items (moderate to severe pain intensity, photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea). There was high correspondence between the item pool and both modified ICHD-3β classification for migraine and Silberstein-Lipton criteria for CM and EM in the two-part models. R2 estimates were 0.98 for migraine detection and 0.96 for CM detection (Table 4). Additional details of psychometric results are provided in Tables 3 and 4 and Web Appendix 2. The final 12 items used for the clinical interviews are presented in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Model fit for IRT modelsa from stage 3.

| EFA Structure | Final 2-part model | |

|---|---|---|

| −2LL | −22,957.6 | −5737.9 |

| AIC | 46,231.3 | 11,517.8 |

| BIC | 47,077.1 | 11,615.7 |

| NBIC | 46,575.2 | 11,549.0 |

2LL: negative two times the log likelihood; AIC: Akaike information criterion; BIC: Bayesian information criterion; EFA: exploratory factor analyses; IRT: item response theory; NBIC: sample size–adjusted Bayesian information criterion.

Smaller values for each fit index indicate better fit of the model.

Table 4.

Stage 3 case-finding tool models.

| Part 1: Migraine screener model |

Part 2: CM screener model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | EST | SE | p | Item | EST | SE | p |

| Migraine loadings | Disability loadings | ||||||

| Q3b: Moderate/severe pain | 1.00 | 0.00 | a | Q11b: Fed-up with HAsc | 1.27 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Q8b: Photophobia | 3.1 | 0.34 | <0.001 | Q12b: HAs interfere with plans | 2.27 | 0.69 | 0.001 |

| Q9b: Phonophobia | 2.6 | 0.26 | <0.001 | Q13b: Worry about making plans | 1.96 | 0.54 | <0.001 |

| Q10b: Nausea | 2.1 | 0.18 | <0.001 | Q16b: Days missed of work/school | 1.39 | 0.21 | <0.001 |

| Q17b: Days of not doing choresc | 0.64 | 0.04 | <0.001 | ||||

| Q18b: Days missed of family/leisure | 1.00 | 0.00 | a | ||||

| Q16b: Days missed of work/school ZINB | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.37 | ||||

| Regression | Regression | ||||||

| Intercept migraine | 4.9 | 0.22 | <0.001 | Intercept disabled | 0.62 | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| OR: migraine → ICHD-3β | 78Kd | 315K | 0.37 | OR: disabled → CM | 1.32 | 0.17 | 0.095 |

| Migraine factor variance | 1.38 | 0.17 | <0.001 | OR: HA_freq_90 → CM | 2.47 | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| R2 | 0.98 | 0.04 | <0.001 | OR: HA_freq_30 → CM | 1.31 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Disabled factor variance | 1.49 | 0.27 | <0.001 | ||||

| R2 | 0.96 | 0.02 | <0.001 | ||||

| Symptom items remained distributed and modeled as multinomial ordered categories | The first three disruption items were distributed and modeled as multinomial ordered categories. All but the first MIDAS item were distributed and modeled as standard negative binomial variates. The MIDAS item assessing days missed of work or school was distributed and modeled as a ZINB variate, and the last loading in the table differentiated by the ZINB descriptor is the zero process loading. | ||||||

CM: chronic migraine; EST: estimate; HA: headache; ICHD-3β: International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version); OR: odds ratio; Q: question; SE: standard error; ZINB: zero-inflated negative binomial; MIDAS: Migraine Disability Assessment.

Item response theory models were estimated using reference identification. Reference item indicated with a in p value column.

Italics indicate the ID-CM items that were used for migraine (Stage 1; four symptom items) and chronic migraine (Stage 2: six items [three disruption and three disability items]) as the model was moved into stage 4.

See Table 1 for full question wording.

Eliminated in the final classification accuracy scoring algorithm, resulting in a 12-item Identify Chronic Migraine (ID-CM) form (Figure 2).

Note that the OR is so large as to be deterministic and not truly interpretable because 100% of the four-item set used for migraine screening was used in the modified ICHD-3β migraine classification. This was not the case for the model in Part 2 for chronic migraine (CM) because the item set was broader than that used in the ICHD-3β migraine classification and the ORs reflect strong but more normative ranges.

Figure 2.

Final 12-item ID-CM tool.

If both the Frequency and Symptoms boxes are checked, the patient may have chronic migraine. If the Medication Use, Activities, and Making Plans boxes are all checked, the patient may have chronic migraine. ID-CM: Identify Chronic Migraine.

Stage 4: Diagnostic validity

Sampling returns

Of the 2923 individuals receiving invitations, 111 individuals (3.8%) met inclusion criteria and provided complete and usable clinical interview data. Figure 1 provides more details on the sampling for this stage. Mean (SD) age of participants was 46.2 (13.4) years, and most were female (82.9%) and white (89.2%) (Table 2). The distribution of the 111 completed cases across clinical interviewers stratified on headache sampling quotas is given in Web Appendix 3 (Supplemental Table 1); PPV values for each clinician ranged from 83.3% to 100%.

Classification accuracy

To screen positive for migraine (EM or CM), respondents had to meet screening criteria on pain and both photophobia and phonophobia or nausea. Classification accuracy of this screening algorithm was strong when compared with clinician diagnosis of migraine (Table 5). The four-item symptom screening tool for migraine had a sensitivity of 83.5%, specificity of 88.5%, and PPV of 96.0%.

Table 5.

Stage 4 classification accuracy for ID-CM.

| Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Negative predictive value, % | Positive predictive value, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migraine screening | ||||

| Four-item ID-CM | 83.5a | 88.5b | 62.2c | 96.0d |

| CM screening | ||||

| Six-item ID-CM | 76.1 | 90.9 | 71.4 | 92.7 |

| Final 12-item ID-CM | 80.6e | 88.6f | 75.0g | 91.5h |

CM: chronic migraine; ID-CM: Identify Chronic Migraine.

The total sample analyzed was N = 111.

n = 85 were diagnosed with migraine.

n = 71 screened positive for migraine on ID-CM.

n = 67 were diagnosed with CM.

n = 59 screened positive for CM on ID-CM.

Calculated from 2 × 2 cell and marginal proportions as 71/85.

Calculated from 2 × 2 cell and marginal proportions as 23/26.

Calculated from 2 × 2 cell and marginal proportions as 23/37.

Calculated from 2 × 2 cell and marginal proportions as 71/74.

Calculated from 2 × 2 cell and marginal proportions as 54/67.

Calculated from 2 × 2 cell and marginal proportions as 39/44.

Calculated from 2 × 2 cell and marginal proportions as 39/52.

Calculated from 2 × 2 cell and marginal proportions as 54/59.

A definition of CM based on criteria for migraine above coupled with headache day criteria (≥15 headache days out of the last 30 days, and ≥45 headache days out of the last 90 days) was assessed for classification accuracy. This approach yielded high specificity but moderate sensitivity. Examination of the misclassified cases revealed, as anticipated, underreporting of headache days on ID-CM. Individuals misclassified by ID-CM as not having CM, but who received CM clinical diagnoses, had high rates of disability, medication use, or planning disruption. Expanding the scoring algorithm of ID-CM to include information on disability, medication use, and planning disruption, but eliminating the disability (i.e. chores) and planning disruption (i.e. fed up) items having the weakest IRT parameters (see model results under Part 2 in Table 4), resulted in a 12-item ID-CM having sensitivity of 80.6%, specificity of 88.6%, NPV of 75.0%, and PPV of 91.5% (Table 5) (see Web Appendix 3 Supplemental Table 1 for more details). Of the 111 stage 4 participants, 67 were diagnosed as having CM by gold-standard clinician interviews; by comparison, the final 12-item ID-CM tool identified 59 participants as CM positive.

Discussion

ID-CM is a two-part case-finding tool that aims to (1) identify individuals with severe headache who have migraine and (2) among individuals with migraine identify those with CM. ID-CM was developed using input from both clinical experts (stage 1) and individuals with CM (stage 2). Following psychometric validation in stage 3, operating characteristics of ID-CM relative to an independent diagnosis assigned by a clinical expert using the SSDI-M was also assessed (stage 4).

ID-CM has been rigorously evaluated and has strong psychometric properties and high classification accuracy both for migraine and CM. Compared with other well-known and highly regarded screening and diagnostic tools for various diseases/disorders (Table 6), the classification accuracy of ID-CM was both absolutely and relatively strong (Table 5). The AMS/AMPP CM screening algorithm has a higher sensitivity (90% vs 81%) and NPV (85% vs 75%), although the specificity (82% vs 89%) and PPV (88% vs 92%) are lower. Differences between these tools may be attributed to differences in sample composition. The AMS/AMPP CM screening assessment was conducted in a clinic-based sample at the New England Headache Center, whereas this study of ID-CM was conducted in a Web-based panel. Clinic-based samples generally contain patients with greater disease severity, which may make case-finding easier, increasing sensitivity estimates. Even after accounting for the potentially easier case detection by virtue of sample composition, ID-CM retains higher specificity and PPV. The sensitivity and specificity achieved by ID-CM compare favorably with those achieved by other screening and diagnostic tests, indicating that it is effective in identifying both migraine and CM.

Table 6.

Classification accuracy for other screening or diagnostic tools.

| Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Negative predictive value, % | Positive predictive value, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migraine screening or diagnosis | ||||

| AMS/AMPP Diagnostic Module (34) | 100 | 82 | Unknown | Unknown |

| ID-Migraine (19) | 81 | 75 | 93 | Unknown |

| CM Diagnosis | ||||

| AMS/AMPP Diagnostic Modulea (22) | 90 | 82 | 85 | 88 |

| Other common screening or diagnostic tools | ||||

| PHQ-9 (depression) (35) | 88 | 88 | Unknown | Unknown |

| PSA (prostate cancer) (36) | 75 | 74 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Pap (cervical cancer) (37) | 44–99 | 91–98 | Unknown | Unknown |

AMPP: American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study; AMS: American Migraine Study; CM: chronic migraine; ID-Migraine: Identify Migraine Screener; PHQ-9: 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; Pap: Papanicolaou.

The AMS/AMPP CM screening assessment was conducted in a clinic-based sample at the New England Headache Center, whereas ID-CM was developed using a Web-based research panel. Clinic-based samples generally involved patients with greater disease severity, which facilitates diagnostic detection, thus increasing sensitivity estimates.

Many of the classification accuracy statistics for the six-item CM tool indicated strong correspondence with clinical diagnosis of CM (Table 5). In fact, the six-item form is a good case-finding tool for CM. However, the sensitivity for the six-item version was lower than desired and lower than that observed for the 12-item CM tool (76% vs 81%). Because the 12-item version had higher sensitivity, we recommend it as a case-detection tool. The additional relevant domains of disability, medication use, and planning disruption not only improve classification, but provide additional data that permit clinicians to evaluate the roles of medication overuse and headache impact when making diagnostic and referral decisions.

This study has several inherent strengths. Item banks were generated from variants of existing validated scales reviewed and selected by an international Delphi Panel of recognized migraine experts. Furthermore, after a Web-based sample from a research panel was used for ID-CM tool validation, rigorous psychometric modeling was employed to arrive at the final item set. In addition, all ID-CM tool diagnoses were compared with gold-standard physician-administered clinical diagnostic interview validation, with review by another physician to rectify discrepancies and confirm adherence to protocol.

The study and ID-CM development also have several limitations. The sample size in the final validation study was limited. The PPV and NPV depend on the base rate of the condition in the study population. In addition, instruments should be validated in the setting of intended use. The sample used for this study was highly selected; thus, results from this Web panel may not be fully generalizable to other settings (e.g. subspecialty headache centers, general neurology, primary care practices) without supplementary analyses. Indeed, although classification accuracy may be lower in less-selected populations (e.g. primary care practices), one may expect that classification accuracy could be higher in specialty clinics because the population of patients seeking care for severe headaches would be higher than within a Web-panel population. Validation in a range of settings and languages is recommended. It should be noted that the concurrent validation data collected, and test-retest reliability assessed in the stage 3 sample with a three-week assessment lag, are not discussed here but will be presented in a forthcoming manuscript. Limitations of this analysis notwithstanding, the extensive development and evaluation process for ID-CM, along with its strong psychometric properties, support its clinical utility as a case-finding tool both for migraine and CM case detection.

Conclusion

The simplicity and accuracy of ID-CM will enable health care professionals with or without training in neurology, pain, or headache to correctly identify the majority of patients with migraine or CM. Clinicians will then be able to accurately diagnose or refer affected patients to specialists for effective treatment that will reduce the burden of illness experienced by those with migraine and CM.

Clinical implications

Of those identified as having migraine by the Identify Chronic Migraine (ID-CM) case-finding tool, using a simple scoring algorithm based on four symptom items (moderate/severe pain intensity, photophobia, phonophobia, migraine-related nausea), 96% were diagnosed with International Classification of Headache Disorders-3β (ICHD-3β) migraine (i.e. positive predictive value (PPV) = 96%). In addition, the tool correctly detected 83.5% of those diagnosed with migraine (i.e. sensitivity = 83.5%).

Of those identified as having CM by ID-CM, using a scoring algorithm based on the four migraine scoring items and eight additional items assessing headache frequency, disability, medication use, and planning disruption, 91.5% were diagnosed with ICHD-3β CM (i.e. PPV = 91.5%). Of those diagnosed with CM, ID-CM correctly detected 80.6% of the cases (i.e. sensitivity = 80.6%).

The simplicity and accuracy of ID-CM will enable health care professionals with or without training in neurology, pain, or headache to correctly identify the majority of patients with migraine or CM.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Valerie Marske (Vedanta Research, Chapel Hill, NC, USA) for her assistance with participant recruitment, clinician training, and administration of the Web-based surveys; C. Mark Sollars, MS (Montefiore Headache Center, Bronx, NY, USA) for his help with study management, BRANY Institutional Review Board submission, and developing and filming the Semistructured Diagnostic Interview for Migraine (SSDI-M) training interview; Michael T. Lynch (TheInfluence.net, New York, NY, USA) for editing and producing the SSDI-M training video; James McGinley, PhD (Vedanta Research, Chapel Hill, NC, USA), who assisted with the migraine classification accuracy analyses; Kristina M. Fanning, PhD (Vedanta Research, Chapel Hill, NC, USA), who assisted with demographic data analyses; Joanna Sanderson, PharmD, MS (formerly of Allergan Inc, Irvine, CA, USA), for her help with study design and management; and Chris Evans, PhD (Endpoint Outcomes, Boston, MA, USA), for his assistance as the Delphi moderator. The authors would also like to give special thanks to Uri Napchan, MD, Tanya Bilchik, MD, Audrey Halpern, MD, and Eric Kung, MD, who conducted many of the phone-based clinical interviews. Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Kristine W. Schuler, MS, and Amanda M. Kelly, MPhil, MSHN, of Complete Healthcare Communications, Inc (Chadds Ford, PA, USA) and Dana Franznick, PharmD, and was funded by Allergan, Inc (Irvine, CA, USA). All authors met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) authorship criteria. Neither honoraria nor payments were made for authorship.

Funding

This work was sponsored by Allergan, Inc (Irvine, CA, USA). The Delphi Panel and cognitive debriefings were conducted by Endpoint Outcomes (Boston, MA, USA), and data collection and analyses were conducted by Vedanta Research (Chapel Hill, NC, USA). Daniel Serrano, PhD, formerly consultant for Vedanta Research and presently employed at Endpoint Outcomes, conducted all psychometric analyses.

Conflict of interest

Financial arrangements of the authors with companies whose products may be related to the present report are listed below, as declared by the authors. Richard B. Lipton, MD, has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund. He serves as consultant, serves as an advisory board member, or has received honoraria from Alder, Allergan, American Headache Society, Autonomic Technologies, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cognimed, Colucid, Eli Lilly & Company, eNeura Therapeutics, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Teva, Inc. Daniel Serrano, PhD, is an employee of and Associate Director of Psychometrics and Statistics at Endpoint Outcomes. This work was completed serving as a consultant for Vedanta Research and he has received support funded by Allergan, Colucid, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, MAP Pharmaceuticals, Merck, NuPathe, Novartis, and Ortho-McNeil, via grants to the National Headache Foundation. Dawn C. Buse, PhD, has received grant support and honoraria from Allergan/MAP Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, NuPathe, and the American Headache Society. She is an employee of Montefiore Headache Center, which has received research support funded by Allergan, Colucid, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, MAP Pharmaceuticals, Merck, NuPathe, Novartis, Ortho-McNeil, and Zogenix, via grants to the National Headache Foundation. Jelena M. Pavlovic, MD, PhD, has received honoraria from Allergan and the American Headache Society. Andrew M. Blumenfeld, MD, within the past 12 months, has served on advisory boards and/or has consulted for Allergan, Zogenix, and Supernus, and has received funding for travel, speaking, and/or royalty payments from IntraMed and Allergan. David W. Dodick, MD, within the past 12 months, has served on advisory boards and has consulted for Allergan, Amgen, Alder, Merck, ENeura, Eli Lilly & Company, Autonomic Technologies, Labrys, Tonix, and Alcobra. Within the past 12 months, Dr Dodick has received royalties, funding for travel, speaking, or editorial activities from the following: Haymarket Media Group Ltd, SAGE Publishing, Synergy, Allergan, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Oxford University Press, and Cambridge University Press; he serves as editor-in-chief of Cephalalgia and on the editorial boards of The Neurologist, Lancet Neurology, and Postgraduate Medicine. He receives publishing royalties for Wolff's Headache, 8th edition (Oxford University Press, 2009) and Handbook of Headache (Cambridge University Press, 2010). Sheena K. Aurora, MD, has received consulting fees/honoraria from Allergan, eNeura, Merck, and Nupathe, and speakers bureau participation for Allergan. Werner J. Becker, MD, has served on advisory boards for Allergan, St Jude Medical, Tribute Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, and ElectroCore; has received compensation for presenting educational lectures from Serono, Tribute Pharmaceuticals, Teva, and Allergan; and has received funding as part of a multicenter clinical trial as the local principal investigator from St Jude Medical and Amgen. Hans-Christoph Diener, MD, has received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards or oral presentations from Addex Pharma, Allergan, Almirall, Autonomic Technology, AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, Berlin Chemie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Coherex, CoLucid, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal, Janssen-Cilag, Eli Lilly, La Roche, 3M Medica, Medtronic, Menarini, Minster, MSD, Neuroscore, Novartis, Johnson & Johnson, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Schaper and Brümmer, Sanofi, St Jude, and Weber & Weber. He has received financial support for research projects from Allergan, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, MSD, and Pfizer. Headache research at the Department of Neurology in Essen is supported by the German Research Council (DFG), the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), and the European Union. Dr Diener has no ownership interest and does not own stock in any pharmaceutical company. Shuu-Jiun Wang, MD, has received personal compensation for consulting, advisory boards, or speaker activities from Allergan, GlaxoSmithKline (Taiwan), Pfizer (Taiwan), and Eli Lilly & Company (Taiwan), and has received research support from Novartis (Taiwan) and Daiichi-Sankyo. Maurice B. Vincent, MD, has received personal compensation for consulting and advisory board activity from Allergan. Nada Hindiyeh, MD, and Amaal J. Starling, MD, have nothing to declare. Patrick J. Gillard, PharmD, MS, and Sepideh F. Varon, PhD, are employees of Allergan and report having received stock and/or stock options from Allergan. Michael L. Reed, PhD, is managing director of Vedanta Research, which has received support funded by Allergan, Colucid, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, MAP Pharmaceuticals, Merck, NuPathe, Novartis, Ortho-McNeil, and Zogenix, via grants to the National Headache Foundation.

References

- 1.Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, et al. Chronic migraine in the population: Burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology 2008; 71: 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buse DC, Lipton RB, Reed ML, et al. Barriers to chronic migraine care: Results of the CaMEO (Chronic Migraine Epidemiology & Outcomes) study. Presented at the International Headache Congress (IHC), Boston, MA, USA, 27–30 June 2013, poster P65.

- 3.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Amatniek JC, et al. Tools for diagnosing migraine and measuring its severity. Headache 2004; 44: 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pracilio VP, Silberstein S, Couto J, et al. Measuring migraine-related quality of care across 10 health plans. Am J Manag Care 2012; 18: e291–e299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cevoli S, D'Amico D, Martelletti P, et al. Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of migraine in Italy: A survey of patients attending for the first time 10 headache centres. Cephalalgia 2009; 29: 1285–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, von Korff M. Burden of migraine: Societal costs and therapeutic opportunities. Neurology 1997; 48(3 Suppl 3): S4–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Fanning KM, et al. Effects of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics on barriers to chronic migraine consultation, diagnosis, and treatment: Results from the CaMEO (Chronic Migraine Epidemiology & Outcomes) Study. Presented at the American Headache Society 2014 Annual Meeting, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 26–29 June 2014, poster P24.

- 8.Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, et al. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010; 81: 428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: Results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache 2012; 52: 1456–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YC, Tang CH, Ng K, et al. Comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine sufferers in a national database in Taiwan. J Headache Pain 2012; 13: 311–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manack AN, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine: Epidemiology and disease burden. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2011; 15: 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamond S, Bigal ME, Silberstein S, et al. Patterns of diagnosis and acute and preventive treatment for migraine in the United States: Results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study. Headache 2007; 47: 355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipton RB, Amatniek JC, Ferrari MD, et al. Migraine. Identifying and removing barriers to care. Neurology 1994; 44(6 Suppl 6): S63–S68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipton RB, Serrano D, Holland S, et al. Barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of migraine: Effects of sex, income, and headache features. Headache 2013; 53: 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams AM, Serrano D, Buse DC, et al. The impact of chronic migraine: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia. Epub ahead of print 10 October 2014. DOI: 10.1177/0333102414552532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.LeFevre M, Bibbins-Domingo K and Siu A. High-priority evidence gaps for clinical preventive services: Fourth annual report to Congress. Rockville, MD: US Preventive Services Task Force, 2014.

- 18.Pill J. The Delphi Method: Substance, context, a critique and an annotated bibliography. Socioecon Plann Sci 1971; 5: 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID Migraine validation study. Neurology 2003; 61: 375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, et al. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology 2001; 56(6 Suppl 1): S20–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, et al. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: The HIT-6. Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 963–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liebenstein M, Bigal M, Sheftell F, et al. Validation of the Chronic Daily Headache Questionnaire (CDH-Q). Presented at the 49th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 7–11 June 2007, abstract F25.

- 23.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: Data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001; 41: 646–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buse DC, Manack AN, Serrano D, et al. Headache impact of chronic and episodic migraine: Results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study. Headache 2012; 52: 3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24(Suppl 1): 9–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Celentano DD, et al. Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States. Relation to age, income, race, and other sociodemographic factors. JAMA 1992; 267: 64–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches: Field trial of revised IHS criteria. Neurology 1996; 47: 871–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Solomon S, et al. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches in the headache clinic. Proposed revisions to the International Headache Society criteria. In: Olesen J. (ed). Frontiers in Headache Research, New York: Raven Press Ltd., 1994, pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Merikangas KR. Reliability in headache diagnosis. Cephalalgia 1993; 13(Suppl 12): 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Ryan RE, Jr, et al. Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine in alleviating migraine headache pain: Three double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Arch Neurol 1998; 55: 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scher AI, Stewart WF, Liberman J, et al. Prevalence of frequent headache in a population sample. Headache 1998; 38: 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Liberman J. Variation in migraine prevalence by race. Neurology 1996; 47: 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jhingran P, Osterhaus JT, Miller DW, et al. Development and validation of the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. Headache 1998; 38: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipton RB, Diamond S, Reed M, et al. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: Results from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001; 41: 638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bangma CH, Kranse R, Blijenberg BG, et al. Free and total prostate-specific antigen in a screened population. Br J Urol 1997; 79: 756–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nanda K, McCrory DC, Myers ER, et al. Accuracy of the Papanicolaou test in screening for and follow-up of cervical cytologic abnormalities: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132: 810–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]