Abstract

Management of homicidal cut-throat injuries requires a multi-disciplinary approach. The role of an anesthesiologist in instituting an airway using an endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy before wound exploration and repair of transected tissues, is challenging, as, such injuries are most of the time associated with distortion of the normal anatomy of the airway. We hereby report a case of 60-year-old lady diagnosed as homicidal cut-throat injury with vocal cords exposed externally and injury of thyroid cartilage and pharyngeal muscles. Patients with cut-throat injury may present with airway compromise, aspiration, and acute blood loss with hypoxemia because of injury to the airway and major vessels. Securing an airway becomes the first priority in patients with cut-throat injuries. It could be done by an endotracheal intubation, cricothyroidotomy, or by an emergency tracheostomy. For the effective management of patients with a cut-throat injury, there is a need for a multidisciplinary approach by a team consisting of an otorhinolaryngologist, anesthesiologist, and a psychiatrist.

Keywords: Airway, anesthesiologists, homicidal cut-throat, vocal cords

INTRODUCTION

Patients with cut-throat injury may present with airway compromise, aspiration, and acute blood loss with hypoxemia because of injury to the airway and major vessels. These injuries may be accidental, suicidal, or homicidal.[1]

Evaluation and management are complicated due to a dense concentration of vital, vascular, aerodigestive, and neurovascular system structures. A good team consisting of anesthesiologists and surgeons (vascular, otolaryngologist) is required to prevent catastrophic airway, vascular, or neurological sequelae. Injury to major vessels (carotid or jugular) may be fatal.[2]

Bubbling of air through the neck wound indicates a perforation of larynx or trachea. The presence of retropharyngeal air seen in the lateral view of the X-ray neck indicates a perforation of either the pharynx or esophagus. LeMay in a study of 25 cases of the penetrating wound of the neck in the Vietnam War found the presence of retropharyngeal air, a good indication of perforation of either the pharynx or esophagus, which may also be demonstrated in barium swallow. However, a negative result does not rule out the possibility of a perforation.[3]

If the victims present without airway compromise, an assessment of the severed tissues is made and meticulous surgical repair effected in the shortest possible time. Securing the airway is the first priority in the management of these patients if the airway is unstable or in the presence of edema. The ideal way to establish airway is orotracheal intubation in the awake patient which is followed by the insertion of a tracheostomy tube through the transected portion of the trachea, if a transection is present. Some authors have described this approach to be dangerous because it can produce further damage to the larynx or increasing the chances of inhaling vomitus, blood, or secretions.[4]

However, a formal tracheostomy can be done in the early phases of presentation to secure the airway, and anesthetic gases can be administered via this in order to carry out repair under general anesthesia (GA). Although in severe airway, compromise reports have been made of airway maintenance with endotracheal intubation alone and there have been reports of the effective use of a fibreoptic laryngoscope to intubate the trachea following a cut-throat injury.[5] This has reduced the need for tracheostomy and its attendant complications. In the event that the trachea is completely transected, a re-anastomosis of the transected ends of the trachea is done.[6]

Regional anesthesia can be tried but the disadvantages are that bilateral vagal block often produce concomitant block of hypoglossal nerve leading to flaccidity of tongue, which might further obstruct the pharyngeal airway and could abolish all the protective reflexes of lower airway. Moreover, these methods are also technically difficult to perform. The preferred technique is awake intubation through the mouth by the conventional method under topical analgesia.[7]

Ideally, pharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal mucosal lacerations should be repaired early because the time elapsed before the repair of laryngeal mucosal lacerations has an effect on both airway stenosis and on voice restoration.[8]

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old elderly lady was admitted in the Department of Ear Nose and Throat (ENT) and Head and Neck Surgery, Karnataka Institute of Medical Sciences, Hubli, with homicidal injury having got her throat slashed with knife. On admission, patient was conscious and oriented with tachypnea, pulse rate of 96 beats/min, and blood pressure of 130/70 mmHg. Patient had come with a history of bleeding from the wound which had got reduced by applying pressure.

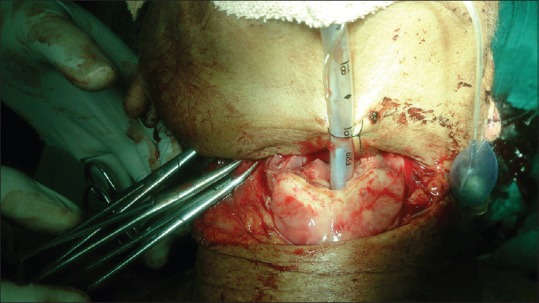

On examining the neck, a horizontal cut-throat wound of around 10 cm × 2 cm size, extending from the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at mid one-third to the opposite side sternocleidomastoid muscle, was seen. Underlying strap muscles were cut and exposed. Thyroid cartilage was cut horizontally and vocal cords were exposed. There was no active bleed. Patient was posted for tracheostomy and suturing of wound under GA.

Under aseptic precautions, after securing a 20 gauge intravenous (i.v.) cannula over the right upper limb, the patient was given oxygen inhalation at 6 L/min over exposed glottic opening. The patient was premedicated with glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg i.v., midazolam 2 mg i.v., and fentanyl 100 mcg i.v.; tracheal intubation was done with an internal diameter of 5.5 cuffed endotracheal tube under vision through the external wound [Figures 1–3]. Bilateral air entry checked, the tube was fixed at 14 cm, and was connected to Bain circuit. Later, on induction dose of propofol 100 mg and vecuronium 4 mg was given i.v. The patient was maintained with nitrous oxide: Oxygen at 5:3 ratio and supplemented with 1 mg doses of vecuronium i.v. every 20 min till the completion of tracheostomy. Other medications given intraoperatively were ranitidine 75 mg i.v., ondansetron 4 mg i.v., and dexamethasone 8 mg i.v. and diclofenac sodium 75 mg i.v. was added to 1 pint of normal saline, tranexamic acid 500 mg i.v. bolus, and 500 mg infusion in 1 pint of ringer lactate. Post tracheostomy, patient was extubated.

Figure 1.

Original picture of the patient taken intraoperatively

Figure 3.

Original picture of the patient taken intraoperatively

Figure 2.

Original picture of the patient taken intraoperatively

Soft-tissue dissection and suturing of the exposed wound was done by an ENT surgeon. Vessels and nerves were intact. The patient had adequate respiratory efforts and was reversed with neostigmine 3 mg i.v. and glycopyrrolate 0.4 mg i.v. Patient was shifted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for observation and then shifted to general ward next day morning.

DISCUSSION

In a case of cut-throat or penetrating injuries of neck, one should keep in mind the possibility of following vital structures being injured such as larynx, pharynx, trachea, esophagus, major neck vessels, nerve roots, and spinal cord.

A multi-disciplinary approach is required in the effective management of the affected patients. This requires the close collaboration of the otolaryngologist, anesthetist, and psychiatrist. The anesthetist secures an uncompromised airway and makes sure the patient is breathing; the otolaryngologist assesses the injury and repairs the severed tissues with the aim of restoration of swallowing, phonation, and breathing. The psychiatrist provides adequate care and supervision during and after the surgical treatment.[9]

Clinical examination and investigations should aim toward detecting any injury to these structures. Investigative procedures should include computed tomographic scan, X-ray of the neck and chest, barium swallow, direct laryngoscopy, and bronchoscopy.[1] However, adequate airway management should not be delayed by radiologic studies because an apparently stable airway can rapidly progress into an acute airway obstruction.[10,11]

Our patient was brought to the hospital within 4 h of homicidal cut-throat injury. These patients are at an increased risk of aspiration of blood that seeps out of the wound site. Hence, securing the airway forms the first priority. We considered intubating the patient through the vocal cords exposed outside through the cut-throat injury with a smaller sized cuffed endotracheal tube before a definite airway management by tracheostomy was done. A smaller sized cuffed endotracheal tube was selected with an intention to minimize a possible laryngeal injury during awake intubation through the exposed cords. After intubation, the cuff was inflated to prevent aspiration and correct placement of the endotracheal tube was confirmed by checking bilateral air entry and capnography.

Later, the patient was given an induction dose of propofol i.v. and definitive airway management was done by surgical tracheostomy. Exploration of the neck wound was done by an experienced otolaryngologist under GA. The injured strap muscles and thyroid cartilage were sutured separately. The primary closure of the neck wound was done.

Postoperatively, the patient was shifted to the ICU and mechanical ventilation was continued for 12 h postoperatively after which she was weaned off the ventilator. A nasogastric tube was put intraoperatively. Feeding was initiated postoperatively after 12 h. The patient was covered by a broad spectrum of antibiotic and analgesics preoperatively, and that was continued in the postoperative period. Two weeks later, tracheostomy tube was removed and the patient was decannulated. Patient was discharged home on a 25th postoperative day with a good quality of voice and with ability to swallow. There were no behavioral abnormalities as documented by the psychiatrist.

Management should be instituted in good time to prevent affordable complication (s). Cut-throat injury complications may be chronic airway obstruction, wound infection, scar, persistent voice changes and dysphagia, and permanent tracheostomy due to laryngeal stenosis.[12]

CONCLUSION

Homicidal cut-throat injury requires a multidisciplinary approach with the collaboration of an anesthesiologist, otolaryngologist, and a psychiatrist. Establishment of a secure airway should be the first priority. Timely intervention in securing an airway prevents further complications such as aspiration of blood and hypoxemia.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Joshi SS, Jagade M, Nichalani S, Bage S, Agarwal S, Pangam N, et al. Technicality of managing cut throat injury. Int J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;2:11–2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijohns.2013.21004 . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar R, Madhusudhan R, Kumar K, Karthik D, Potli S. Cut throat injuries – A challenge for airway and anaesthetic management – Case report of 5 cases. Int J Curr Sci Res. 2011;1:137–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeMay SR., Jr Penetrating wounds of the larynx and cervical trachea. Arch Otolaryngol. 1971;94:558–65. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1971.00770070858011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaefer SD, Close LG. Acute management of laryngeal trauma. Update. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989;98:98–104. doi: 10.1177/000348948909800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkatachalam SG, Selvaraj DA, Rangarajan M, Mani K, Palanivelu C. An unusual case of penetrating tracheal (“cut throat”) injury due to chain snatching: The ideal airway management. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2007;11:151–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adeyi AA. Suicidal Cut Throat Injuries: Management Modalities, Mental Illnesses - Understanding, Prediction and Control. Prof. Luciano LAbate Editor. 2012. ISBN: 978-953-307-662-1, InTech, Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/mental-illnesses-understanding-prediction-and-control/suicidal-cutthroat-injuries-management-modalities .

- 7.Peralta R, Hurford WE. Airway trauma. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2000;38:111–27. doi: 10.1097/00004311-200007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leopold DA. Laryngeal trauma. A historical comparison of treatment methods. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:106–12. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1983.00800160040010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adoga AA, Ma'an ND, Embu HY, Obindo TJ. Management of suicidal cut throat injuries in a developing nation: Three case reports. Cases J. 2010;3:65. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-3-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao PM, Noveline RA, Dobins JM. The spherical endotracheal tube cuff: A plain radiographic sign of tracheal injury. Emerg Radiol. 1996;3:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez RP, Falimirski M, Holevar MR, Turk B. Penetrating zone ll neck injury: Does dynamic computed tomographic scan contribute to the diagnostic sensitivity of physical examination for surgically significant injury. A prospective blinded study? J Trauma. 2003;54:61–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adebola SO, Ologe FE, Ogunkeyede SA. Penetrating anterior neck injury: A multidisciplinary approach. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 2014;13:20–4. [Google Scholar]