Abstract

Objective

The objective of our study was to examine HIV testing practices among a large sample of women living in public housing in Puerto Rico and the relationships among HIV testing, sociodemographic variables, and HIV-related behaviors.

Methods

A total of 1138 women were surveyed between April and August 2006 using a self-administered survey instrument.

Results

Eighty-two percent of the women in the sample group reported a history of HIV testing. Hierarchical logistic regression analyses revealed that those adults who were at least 25 years of age and those who perceived some risk of HIV were more likely to report previous HIV testing. Also, those who had attended an HIV/AIDS education workshop or discussion and those who reported knowing persons living with HIV/AIDS were more likely to report previous testing.

Conclusions

A large percentage of the women in our study have been tested for HIV; it is imperative, however, that appropriate HIV education and prevention messages be given to them when they receive their results. Client-initiated HIV testing to learn HIV status provided through counseling and testing remains critical to the effectiveness of HIV prevention. It is unwise to underestimate the importance of being tested. One of the first steps in self-protection from HIV is to be informed of one’s HIV status, which allows one to make appropriate and responsible sexual decisions. Future success in decreasing the number of new infections among women will result from targeting women who may be at high risk, although not because of sex work or drug use. Increasing knowledge of HIV serostatus and the implications of these results, especially among those who are infected, can serve as a gateway to sustained behavioral risk reduction intervention, as well as to care and treatment. Considering the fact that both the actual and estimated numbers of HIV/AIDS cases among women in Puerto Rico continue to increase, it is clear that effective, targeted, and aggressive strategies are urgently needed to prevent both primary and secondary HIV transmission.

INTRODUCTION

Entering its third decade, the HIV/AIDS epidemic continues to pose a major public health problem. As of December 2006, it is estimated that approximately 250,000 persons (range 190,000– 320,000) are living with HIV or AIDS in the Caribbean. Overall, an estimated 1.2% of the adult population in the Caribbean region aged 15–49 years is living with the disease, with prevalence as high as 5% in countries like Haiti and with women making up 50% of the cases. This region has the second highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS among adults in the world (second only to the Sub-Saharan Africa region).1 In Puerto Rico, 31,798 cases of AIDS have been reported as of April 20072; however, because of the lack of standardized testing, the actual number of cases may be significantly higher.3 Among all U.S. states and territories, Puerto Rico ranks third in the estimated rates for adults and adolescents living with HIV/AIDS and fourth in reported AIDS cases.4 Historically, the primary mode of transmission for HIV in Puerto Rico has been injecting drug use (IDU), accounting for 50% of all cases among adults since 1981.2 Heterosexual transmission accounts for 25%; among women, however, heterosexual transmission accounts for 61% of the cases, followed by IDU at 37%. Reported cases diagnosed among women constitute 24% of the total cases. Although AIDS cases have been decreasing in males in Puerto Rico since 1993, the number of female cases has shown no such decline. For example, between December 2003 and December 2006, reported cases among women constituted 30% of total cases.2,5 No official estimates of HIV prevalence among the adult population or subpopulations in Puerto Rico are available, but small-scale studies of various samples have found rates between 1% among pregnant women and as high as 36% among IDUs.6,7

Prevention programs have been promoting HIV testing as one possible way to combat the spread of the disease.8,9 This strategy is based on the assumption that knowing their status enables individuals to initiate or maintain behaviors to prevent acquisition or further transmission of HIV as well as to be educated about care, treatment, and support.10 Although HIV testing is promoted as a prevention strategy with various populations, previous research examining the relationship between HIV testing and subsequent protective behavior has produced mixed results; some studies demonstrate a significant relationship between the awareness of one’s HIV serostatus and protective sexual behaviors; others reveal no such link.11,12

HIV risk among Latina women may have implications beyond those of the general population of persons of receiving HIV testing and counseling. As frequently is the case in Latino societies, children born into the Puerto Rican culture find themselves subject to attitudes, mores, and customs that promote very strong gender differences. From birth on, these differences are inherent in every aspect of sexual expression and male-female interaction.13 The outward manifestation of the principle illustrated by these differences is called machismo, which is the belief that males are physically, intellectually, culturally, and sexually superior to females.13 Operating under this attitude, women are relegated to the role of sexual objects, with the sole aim of fulfilling men’s desires and needs.14 Furthermore, in Puerto Rico, these ideas are more prevalent among members of the low-income population, who tend to agree with the more traditional values as related to gender.15 This marked difference in gender roles may lead to increased levels of intimate partner violence (IPV). For example, a cross-cultural comparison of marital abuse revealed high levels of domestic violence in Puerto Rico.16 It is especially prevalent in disadvantaged areas, such as low-income housing, where the combination of poverty, low socioeconomic status, and unemployment seems to perpetuate violence.17

This is of critical importance in light of the association between increased HIV risk and IPV that has been documented in prior studies.18 Other research has found that not just physical violence but the threat of violence coupled with the fear of abandonment act as significant barriers for women who have to negotiate the use of a condom, discuss fidelity with their partners, or leave relationships that they perceive to be risky.19,20 In addition, a history of sexual assault has also been found to be significantly associated with numerous behaviors that place women at greater risk of HIV infection.21 A study of 436 homeless and low-income housed mothers living in Massachusetts found that a history of childhood sexual abuse and adult partner violence significantly increased the likelihood of high-risk behaviors by women.22 Another study comparing HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in Maryland found that HIV-positive women were more likely to experience a higher frequency of violent episodes than were HIV-negative women; in addition, condoms were less likely to be used in those relationships in which the women were repeatedly abused by her partner.23

The relationship between negative partner reactions and sex roles was examined by another study, as was the way in which said reactions influenced subsequent condom use. A study of 187 Puerto Rican women aged 18–35 years in New York City attempted to determine if negative partner reactions to requests for condom use predicted lower levels of condom use among these women.24 In addition, among those women who asked their partners to use a condom, negative partner reactions tended to have a stronger influence on condom use for women with traditional beliefs about sex roles than they did on women with nontraditional beliefs. These findings have serious implications for HIV-prevention interventions that seek to enhance women’s ability to negotiate safer sex. Fear of violence will prevent many women from negotiating safer sex with their partners. In addition, the effects of abuse, including low self-esteem, shame, isolation, and fear of abandonment, inhibit women from seeking information and support about HIV prevention, including HIV testing services.25

Unique cultural and social factors exist that may significantly exacerbate HIV/sexually transmitted infections (STI) risks for impoverished Latina women living in public housing in Puerto Rico. These factors must be measured and considered if one is to develop culturally appropriate, effective interventions to decrease HIV/STI risk-related behaviors among these women. In-nercity, low-income housing developments are an appropriate and important setting for HIV/STI epidemiological and behavioral research and subsequent HIV risk-reduction interventions. Previous research with impoverished women living in public housing outside Puerto Rico has indicated an increased risk of HIV acquisition and transmission as a consequence of various individual (e.g., drug use, sex behaviors) and social factors (e.g., cultural and gender norms, social networks).26,27 Considering the additional cultural and social factors present, impoverished Latina women living in public housing in Puerto Rico may be at a significantly higher risk for HIV/STI than their U.S. peers.

It is important to discuss economic inequality, which is related to gender inequality. Economic inequality in the developing world contributes to a significant number of women in a society engaging in what may be termed “survival sex.” Poor women may resort to exchanging sex for either money or goods. This occurs not only under the rubric of commercial sex work but also in other forms of sexual exchange. Most of this sex is unsafe because women risk loss of economic support from men by insisting on safer sex.28

Given these patterns and inequalities in the roles of women and men, it is not surprising that women are at high risk for HIV transmission, especially those who live in societies that subscribe to the concept of machismo and support gender inequality. The focus on gender relations means that it is important to understand the cultural and social norms that shape behavior. Therefore, research into HIV prevention efforts needs to explore the various social, psychological, and behavioral constructs and how they combine to increase women’s vulnerability to HIV. By developing an understanding of these constructions, one can begin to develop and implement appropriate and effective strategies to improve women’s situations.

It is important to note that although women are more vulnerable than men to HIV/AIDS, statistics suggest that not all women are equally vulnerable to infection. Thus, not only is a woman’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS rooted in a variety of sexual, social, and economic inequalities based on gender, but that gender inequality is further fragmented by a combination of factors, such as race, class, urban/rural residence, sexual orientation, religion, and culture.29

Although anecdotal information suggests that there is a relationship between socioeconomic status and HIV risk, there have been few investigations into that possible relationship. One study investigated the relationship between indicators of socioeconomic status and HIV prevalence in Massachusetts using seroprevalence data from publicly funded test sites. The study showed that residents in low-income areas (identified by ZIP codes) were four times more likely to have high seroprevalence rates among those voluntarily tested for HIV.30 Another study in Los Angeles found similar results. U.S. census data were used to classify ZIP codes by median household income; AIDS rates, based on diagnosed cases, were calculated for each income stratum. The AIDS rate was highest among residents of low-income areas compared with both intermediate and high-income areas (252.8 per 100,000 vs. 161.2 per 100,000 and 82.0 per 100,000, respectively).31 Another study, using HIV seropositivity data from the main HIV counseling and testing clinic for high-risk persons in Seattle, found that clients with lower income were more likely to be HIV seropositive before and after controlling for other demographic and risk factors.32 The findings from these studies suggest that impoverished persons are at increased for HIV infection because of the physical, psychological, and social circumstances in which their poverty places them. Furthermore, these findings provide evidence that there is a need for HIV-related research and subsequent prevention and intervention programs targeting low-income persons.

A review of the published Caribbean-based literature that specifically examined correlates of HIV testing found few studies that specifically addressed such correlates. One study of at-risk persons from Trinidad found that individuals who were tested for HIV and who subsequently received counseling decreased their high-risk sexual behaviors with nonprimary partners but not with primary or steady partners.33 A Jamaican-based study of a sample of university students found that less than half had been tested for HIV. In addition, the study indicated that having been tested was not associated with a later reduction of high-risk behavior, such as inconsistent condom use.34 These findings were similar to those from a national level study of Jamaican adults that showed low levels of testing and no associations with subsequent protective behavior adoption.35

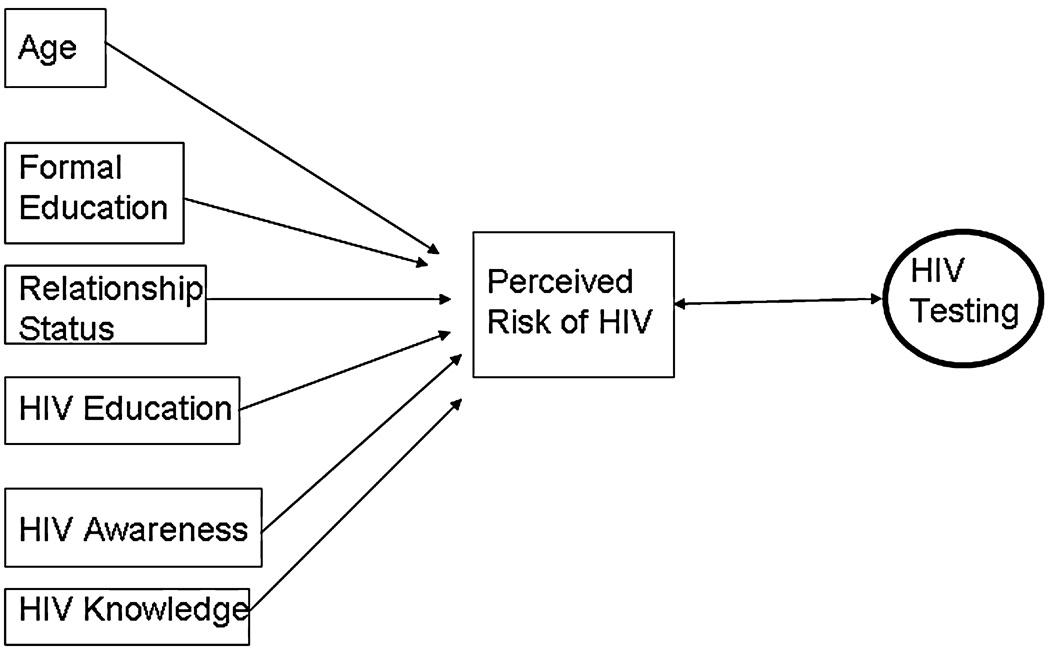

Even fewer studies were identified that examined correlates of HIV testing in Puerto Rican populations living in Puerto Rico. A study of Puerto Rican youths in drug treatment revealed that 66% of those enrolled in ambulatory drug treatment centers agreed to take an HIV test; volunteers, when compared with nonvolunteers, were more likely to be males who reported fewer years of education and who engaged in risky sexual and drug-related behaviors.36 With respect to posttest behaviors, a study of adult drug users in Puerto Rico found that after receiving a positive test result, study subjects were significantly less likely to continue to engage in unprotected vaginal sex.37 Another study of IDUs in Puerto Rico that examined the behavioral effects of receiving HIV test indicated that HIV-positive IDUs were significantly less likely to report being sexually active and more likely to use condoms during vaginal and oral sex.38 However, only studies examining correlates of HIV testing among women who were IDUs, crack cocaine users, or sex workers in Puerto Rico were identified. No other studies were identified that focused on women who may not be members of these risk groups. This is especially critical for those women in lower socioeconomic groups who may not be members of these subpopulations. A review of surveillance and research data indicates that HIV/AIDS is disproportionately represented among minority women and those of lower socioeconomic groups in both the developed and developing world.30,32,39 Therefore, in an attempt to address the apparent gap in HIV testing research among women in Puerto Rico, relevant research with other populations was used to inform the development of an explanatory model that could be used to further examine the behavior changes that arise following HIV testing. The hierarchical model that follows was developed using submodels that reflect the various factors hypothesized to be related to HIV testing:

Submodel 1. Sociodemographic characteristics (age, formal education, employment status, relationship status, HIV awareness, HIV education, HIV knowledge, HIV testing history) are directly related to perceived risk of HIV. Previous research indicates that perceived risk of HIV varies by sociodemographic characteristics.34–36

Submodel 2. Perceived risk of HIV is directly related to HIV testing. Perceived risk has been found in previous studies to be associated with HIV-testing behaviors.40–44

The present study seeks to identify the predictors of HIV testing (sociodemographics, perceived risk of HIV). In addition, it examines subsequent sexual-related behaviors as a result of HIV testing results. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model for the present study analyses.

FIG. 1.

Conceptual model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection

Data for these analyses were taken from the Proyecto MUCHAS, an HIV risk-reduction project targeting women living in public housing in Ponce, Puerto Rico. A 219-item baseline questionnaire was developed related to HIV/AIDS education and prevention. The questionnaire was based on social-psychological theories of behavior change, including the Health Belief Model, Theory of Reasoned Action, and Social Cognitive Theory.10,45,46 Theoretical variables drawn from these theories included perceived risk, perception of norms, and self-efficacy with respect to condom use. In addition, instruments from other Caribbean studies and from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were used to facilitate the development and inclusion of standard questions that have been found to employ reliable and valid measures of HIV-related attitudes and behaviors across various samples.47,48

Our survey instrument was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board, Ponce School of Medicine, and included items addressing knowledge of transmission, knowledge of risks associated with specific sexual behaviors, attitudes toward persons living with HIV/AIDS, HIV-testing behaviors, sexual history, attitudes toward condoms and safer sex, sexual behaviors by steady and nonsteady sex partners, and drug and alcohol use.

The instrument was piloted with a sample of 30 women in order to assess the ease of completing the instrument, to determine if the questions were easily understood, and to ensure that the instrument could be completed in a timely fashion. On the basis of the first piloting phase, revisions were made, and the instrument was piloted again with 10 women during a focus group session. Following the results of the focus group discussion regarding the survey instrument, minor revisions were made, and the instrument was finalized. Women completed the assessments in the community center room within each housing development. Informed consent was received from every respondent. Because of the nature of the questions and the possible perceived threat of addressing issues of a sexual nature, the instrument was self-administered with no identifiers, providing anonymity to the respondents. Research assistants provided support for those women who were unable to read the questionnaire or who needed other assistance by reading the survey to them or completing the survey on their behalf. Each woman received $10 as compensation for completing the survey. All surveys were administered in Spanish. This survey was a baseline, formative survey, occurring before any intervention activities.

Eligibility criteria included being female and a resident of the public housing development. A nonprobability sampling approach was employed for the study. Once a public housing development was selected, posters were placed up to announce that the project would be coming to the public housing development on a certain date and invited all women to come to the community center and participate in the study. All eligible women were invited to participate. Data were gathered between April and August 2006 from 1138 women in 23 various public housing developments across the city of Ponce.

Variables

A number of variables were used in these analyses. Some variables were recoded to facilitate the logistic regression analyses. The following operationalizations were used:

HIV testing

Persons were asked whether they had ever had an HIV test; responses were categorized as Yes or No.

Consistent condom use

Frequency of condom use (with the participant’s most recent sexual partner) was measured and examined separately by partner type. A steady sexual partner was defined as “Someone with whom you [the respondent] have sexual intercourse on a regular or consistent basis, such as a husband or boyfriend.” A nonsteady sexual partner was defined as “Someone with whom you [the respondent] have sexual intercourse, but only occasionally or even just once.” For both partner types, those who reported using condoms every time with their most recent sexual partner (in the 3 months prior to the survey) were coded as consistent condom users. Remaining persons who reported using condoms most times, occasionally, or never were coded as inconsistent condom users.

Condom use at last sex

Condom use at last sex (with the participant’s most recent sexual partner) was measured and examined separately by partner type. Those who reported using a condom were coded as using condoms, and remaining respondents were coded as not using condoms.

Multiple sex partners

Women reporting two or more sex partners in the 3 and 12 months prior to the survey were coded as having multiple sexual partners, and those with one or no partner were coded as not having multiple sexual partners.

Perceived risk of HIV

Women were asked to report their perceived chance of contracting HIV. Response categories included good chance, moderate chance, little chance, and no chance. Responses were dichotomized into categories of some chance (good/moderate/little) and no chance.

HIV education

Women were asked if they had attended a workshop, talk/discussion, or session about HIV/AIDS in the 12 months before the survey. Those who reported attending such an activity were coded as receiving HIV/AIDS education, and remaining persons were coded as not receiving HIV/AIDS education.

HIV awareness

Respondents were asked if they knew someone who was infected/living with HIV/AIDS or who had died from AIDS. Those responding “Yes, a family member or close friend” were coded as having a close, personal awareness of HIV, whereas those reporting “Yes, but not a family member or close friend” were coded as having some personal awareness of HIV; those reporting knowing no such person were coded as having no personal awareness of HIV.

Employment status

Women were asked to report their employment status. Responses were dichotomized in the following categories: Yes, employed full/part-time; and No, unemployed.

Formal education

Respondents were asked to report the last level of schooling they had completed. Responses were dichotomized into the following groups: at least high school education and less than high school education.

HIV knowledge: Viable and nonviable modes of transmission

Participants were asked to indicate which—if any—of the following modes of HIV transmission they believed to be viable: biting, mother-to-child (i.e., breastfeeding, pregnancy), unprotected oral sex, unprotected anal sex, unprotected vaginal sex, ear piercing, navel piercing, tattooing, a blood transfusion (during surgery), and sharing a razor. Each of the listed modes that the participant marked as viable was considered to be a correct answer, meaning that the participant was considered to have accurate knowledge about that particular mode. One point was awarded for each correct answer; incorrect answers were coded as zero. A summary score was calculated by adding the number of correct responses for the 11 items.

To measure knowledge of nonviable modes of transmission, participants were asked indicate which—if any—of the following modes of HIV transmission they believed to be viable: sharing food, being bitten by a mosquito, coming into contact with the urine, spit, sweat, or tears of an HIV/AIDS-infected individual, using a toilet seat or drinking fountain after it has been used by an HIV/AIDS-infected individual, giving blood, and touching the corpse of a person who died of AIDS. Those participants who did not check any of the given modes as viable were coded as having correct knowledge concerning nonviable modes of HIV transmission. A participant who checked any one of the given modes as viable was said to have inaccurate knowledge of HIV transmission in regard to that specific mode. One point was awarded for each correct answer; incorrect answers were coded as zero. A summary score was calculated by adding the number of correct responses for the 10 items. An overall knowledge summary score was calculated by summing the scores from the viable and nonviable scales.

Age

Women were asked to report their age, in years, on their last birthday. Those who reported being age <25 were coded as youths, whereas those ≥25 years were coded as adults. This categorization was based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of youth.49 Those who reported being at least 25 years of age were further categorized as younger adults (aged 25–39 years) and older adults (aged 40+ years). This additional categorization is based on evidence that middle-aged and older adults (those aged ≥40 years) in Puerto Rico are at an increasing risk of HIV, constituting 40% of reported AIDS cases through December 2006.2

Data analysis

Both bivariate (chi-square analyses) and multivariate (hierarchical logistic regression) analyses were employed. Chi-square analyses were used to examine the differences in proportions between persons who reported previous HIV testing and those with no previous HIV testing. In addition, in order to understand the relationship among all the model variables with respect to the dependent variables of interest, hierarchical logistic regression modeling was used. This type of regression analysis takes an iterative form; an initial simple model is followed by more complex models in which the dependent variable from the immediately preceding model becomes a predictor along with the previous predictors.50 All model variables have been dichotomized or tri-chotomized to facilitate the logistic regression analyses. In addition, age-specific multivariate analyses were employed to examine the relationships separately for HIV testing and the independent variables by age group because of the increased number of cases among youth and older adults in Puerto Rico.2 Variables selected for the regression analyses were based on previous research findings that indicate that the variables are important in predicting HIV risk and HIV testing practices.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The mean age of the sample was 36.78 years (standard deviation [SD] 12.31). The women had, on average, 3.13 children (SD 2.11), with 2.1 children (SD 1.60) residing with them. Approximately half of the women were either legally married (11.2%) or involved in a commonlaw relationship (38.6%). Less than one third (28.9%) reported being single, never married, with the remaining women reporting being separated, divorced, or widowed (21.4%). The overwhelming majority of women were unemployed (88.6%), with <5% working full-time (at least 30 hours/week) (4.2%). Slightly more than half of the respondents reported having completed high school (57.7%). A slight minority reported having attended a lecture, course, or community forum about HIV/AIDS in the last year (44.0%). Most of women reported knowing someone living with HIV/AIDS or who had died from the disease (82.0%), with most of those reporting that this person was a family member or friend (61.1%).

The majority of women reported a history of HIV testing (82%). Among those with a history of testing, the vast majority of tested persons (95.4%) reported knowing the results of their test, with 93.5% of those reporting knowing their results reporting a negative test result, 3% reporting a positive result, 3.5% reporting they did not know, and the rest refusing to say. Consistent condom use was low; slightly more than one tenth (11.4%) of those with a steady partner reported consistent condom use during the 3 months prior to the survey. Among those with a recent nonsteady partner, consistent condom use was higher (22.9%). A minority of women reported having multiple sex partners in the 3 and 12 months prior to the survey (9.5% and 13.3%, respectively). Although participation in HIV protective behaviors was low, the majority of women reported being at no or not much risk of HIV (62.5%).

Bivariate models

Table 1 presents the results of the bivariate analysis of HIV testing and selected independent variables. A number of statistically significant relationships emerged. Overall, women who reported previous HIV testing, compared with those with no history of testing, were more likely to be younger adults (aged 25–39) as opposed to those who were younger (<25 years of age) and older (≥40 years of age). They were also more likely to know someone who is or had been infected with HIV as well as to have attended an HIV educational or community forum. Those who perceived themselves to be at some risk of HIV were more likely to report a history of HIV testing.

Table 1.

Bivariate Results for Selected Sociodemographic, Attitudinal, and Behavioral Variables by HIV Testing (n = 1133)

| Variable | Tested n (%)a |

Untested n (%)a |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| <25 | 156 (70.9) | 64 (29.1) | |

| 25–39 | 385 (91.2) | 37 (8.8) | <0.0001 |

| >40 | 368 (78.8) | 99 (21.2) | |

| Formal education | |||

| 6th grade or less | 111 (81.0) | 26 (19.0) | |

| 7th–9th grade | 270 (83.3) | 54 (16.7) | 0.928 |

| High school | 427 (82.8) | 89 (17.2) | |

| Posthigh school | 88 (81.5) | 20 (18.5) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 105 (84.0) | 20 (16.0) | |

| Unemployed | 795 (81.5) | 180 (18.5) | 0.502 |

| Relationship status | |||

| Married/common law | 458 (82.5) | 97 (17.5) | |

| Single | 254 (79.4) | 66 (20.6) | 0.406 |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 199 (83.3) | 40 (16.7) | |

| HIV personal awareness | |||

| Yes, family members/friends | 582 (85.3) | 100 (14.7) | |

| Yes, not family members/friends | 190 (80.9) | 45 (19.1) | <0.0000 |

| No/don’t know | 143 (71.1) | 58 (28.9) | |

| HIV education in previous 12 months | |||

| Yes | 450 (91.1) | 44 (8.9) | |

| No | 470 (75.0) | 157 (25.0) | <0.0000 |

| Perceived risk of HIV | |||

| Some risk | 406 (84.9) | 72 (15.1) | |

| No risk | 392 (76.7) | 119 (23.3) | 0.001 |

| Condom use with most recent steady sex partner in previous 3 months | |||

| Consistent | 77 (81.9) | 17 (18.1) | |

| Inconsistent | 611 (83.6) | 120 (16.4) | 0.682 |

| Condom use with most recent non-steady sex partner in previous 3 months | |||

| Consistent | 29 (82.9) | 6 (17.1) | |

| Inconsistent | 102 (87.9) | 14 (12.1) | 0.255 |

| Condom use at last sex with most recent steady sex partner | |||

| Yes | 119 (80.4) | 29 (19.6) | |

| No | 586 (83.7) | 114 (16.3) | 0.329 |

| Condom use at last sex with most recent non-steady sex partner | |||

| Yes | 39 (83.0) | 8 (17.0) | |

| No | 100 (87.0) | 15 (13.0) | 0.510 |

| Number of sex partners in previous 3 months | |||

| ≥2 | 81 (83.5) | 16 (16.5) | |

| ≤1 | 768 (83.2) | 155 (16.8) | 0.940 |

| Number of sex partners in previous 12 months | |||

| ≥2 | 115 (84.6) | 21 (15.4) | |

| ≤1 | 732 (82.9) | 151 (17.1) | 0.631 |

Valid percentages presented based on number of respondents providing data for each measure.

Reasons for not having an HIV test

The primary reasons given for not testing were no perceived need because they were not at risk (50.5%) and no perceived need because of being seronegative (19.6%). Also, some women reported not knowing where to go to get tested (15.7%). A small percentage (8.8%) reported being scared of finding out they were HIV positive; an equally small percentage (7.3%) claimed to be embarrassed to get tested.

To whom results were disclosed

HIV-seropositive women were most likely to report disclosing the results to their family members (70.7%), followed by their personal doctor (51.9%) and then friends (33.3%). Less than one third of seropositive subjects disclosed to their primary sex partner (29.6%). HIV-seronegative women were also most likely to disclose to their family members (53.5%), followed by their primary sex partner (40.1%). Only a very small number of HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women disclosed to occasional sex partners (11.1% and 4.9%, respectively).

Behavioral changes made as a result of HIV testing

Table 2 shows the behavioral changes reported as a result of HIV testing (among those with a history of HIV testing and reporting results). Only one third of the HIV-seropositive women reported having only one sex partner now, as well as not having changed their behavior (33.3%). Only 14.8% reported using condoms regularly, with less than one fifth (18.5%) reporting having safer sex now. The distribution of behavioral changes among the HIV-seronegative group was quite different. The majority reported limiting themselves to only one sex partner at a time (56.4%); this was followed by having safer sex (19.5%). Approximately one quarter of the seronegative sample reported not having changed their behavior as a result of their testing result (24.3%). A small percentage reported using condoms regularly (8.9%). However, a small percentage reported engaging in unsafe sex (5.8%), and a relatively small fraction (1.7%) reporting having more sex partners than before they were tested.

Table 2.

Behavioral Changes Made as Result of HIV Testing among Those Receiving and Reporting Test Results ( n = 859)

| Behavioral changea | Positive result (n = 27) n (%) |

Negative result (n = 832) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Have only one sex partner | 9 (33.3) | 469 (56.4) |

| Have safer sex now | 5 (18.5) | 162 (19.5) |

| Stopped having sex | 3 (11.1) | 90 (10.8) |

| Use condoms regularly | 4 (14.8) | 74 (8.9) |

| Have unsafe sex now | 1 (3.7) | 48 (5.8) |

| Have less sex partners | 2 (7.4) | 20 (2.4) |

| Have more sex partners | 0 (0.0) | 14 (1.7) |

| Have not changed behavior | 9 (33.3) | 202 (24.3) |

| Otherb | 1 (3.7) | 4 (0.0) |

Categories are not mutually exclusive.

Includes not having a sex partner.

Multivariate models

Table 3 presents the results of the hierarchical logistic regression analyses for the total, unstratified sample. The hierarchical model consists of two submodels, which were statistically significant, with p < 0.01.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Logistic Regression Results: Total Sample

| Model and independent variablesa | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|

| Submodel 1: Perceived HIV risk (n = 875) | |

| Age, years | |

| 25–39 | 1.17 (0.80–1.71) |

| 40 + | 1.09 (0.75–1.58) |

| Formal education | 1.27 (0.96–1.67)† |

| Employment status | 1.71 (1.10–2.67)* |

| Relationship status | 0.90 (0.69–1.19) |

| HIV awareness | |

| Know family/friends | 1.50 (1.02–2.19)* |

| Know someone/not family/friend | 1.08 (0.70–1.70) |

| HIV education | 0.89 (0.67–1.18) |

| HIV knowledge | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) |

| HIV testing | 1.59 (1.10–2.29)* |

| Submodel 2: HIV testing (n = 875) | |

| Age, years | |

| 25–39 | 5.07 (3.03–8.47)*** |

| 40 + | 2.07 (1.34–3.21)** |

| Formal education | 0.87 (0.60–1.26) |

| Employment status | 1.39 (0.73–2.67) |

| Relationship status | 1.10 (0.77–1.58) |

| HIV awareness | |

| Know family/friends | 1.86 (1.19–2.92)** |

| Know someone/not family/friend | 1.56 (0.91–2.69) |

| HIV education | 3.82 (2.51–5.79)*** |

| HIV knowledge | 1.02 (0.95–1.10) |

| Perceived HIV risk | 1.60 (1.11–2.32)* |

The reference group for each variable is a follows: age (<25 years); education (less than high school); employment status (unemployed); relationship status (unstable— single/separated/divorced/widowed); HIV awareness (no/don’t know anyone); HIV education (no previous formal HIV education); perceived HIV risk (no risk); and HIV testing (no previous HIV test).

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001;

p < 0.10.

When examining predictors of perceived risk of HIV, three independent variables emerged as statistically significant. Women who were employed were more likely than those unemployed to perceived some risk of HIV (odds ratio [OR] 1.71, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.10–2.67). Also, women who knew a family member or friend who had HIV were more likely to perceive some risk of HIV than were those who did not know anyone living with the disease (OR 1.50, CI 1.02–2.19). Lastly, women who reported a history of HIV testing were more likely to perceive themselves at risk for HIV than were those with no history of testing (OR 1.59, CI 1.10–2.29).

When examining predictors of history of HIV testing, five of the eight independent variables were significant. Adults, both 25–39 years of age and those ≥40 years, compared to youth (<25 years) were more likely to report ever having been tested for HIV (OR 5.07, CI 3.03–8.47 and OR 2.07, CI 1.34–3.21, respectively). Women who had a family member or friend living with HIV were more likely to report a history of testing than were women who reported knowing no such person (OR 1.86, CI 1.19–2.92). HIV education and awareness were associated with HIV testing; women who reported attending an HIV education forum/discussion were also more likely to report a previous HIV test than those with no previous HIV education (OR 3.82, CI 2.51–5.79). Finally, those who perceived themselves at some risk of HIV were more likely to report having been tested for HIV than those who perceived themselves to be at no risk for HIV (OR 1.60, CI 1.11–2.32).

Multivariate models stratified by age

Because of the differences in HIV testing between youths and adults and the reported increases in cases among youths and older adults, separate hierarchical logistic models were examined for each subgroup. Table 4 shows the results of the hierarchical logistic regression analyses for the sample as stratified by age. The hierarchical model consists of two submodels that were examined by the separate categories of youths, younger adults, and older adults (six total submodels). All three models in which HIV testing was the dependent variable were statistically significant.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Logistic Regression Analyses Examining Perceived Risk of HIV and History of HIV Testing by Age

| Model and independent variablesa |

Youth (<25 years) Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

Younger adults (25–39 years) Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

Older adults (40+ years) Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Submodel 1: Perceived HIV risk | n = 176 | n = 333 | n = 366 |

| Formal education | 1.24 (0.66–2.33) | 1.37(0.87–2.17) | 1.22 (0.79–1.88) |

| Employment status | 1.03 (0.37–2.87) | 1.52 (0.75–3.08) | 2.57(1.23–5.37)* |

| Relationship status | 0.88 (0.48–1.62) | 0.70 (0.44–1.09) | 1.15 (0.75–1.77) |

| HIV awareness | |||

| Know family/friend | 1.49 (0.68–3.27) | 1.51 (0.79–2.87) | 1.37(0.76–2.51) |

| Know someone/not family/friend | 1.38 (0.56–3.40) | 0.82 (0.38–1.76) | 1.18 (0.58–2.42) |

| HIV education | 0.68 (0.36–1.29) | 0.95 (0.60–1.51) | 0.92 (0.59–1.44) |

| HIV knowledge | 1.00 (0.88–1.15) | 1.03 (0.94–1.12) | 1.01 (0.94–1.10) |

| HIV testing | 1.72 (0.86–3.42) | 1.83 (0.81–4.12) | 1.49 (0.87–2.53) |

| Submodel 2: HIV testing | n = 176 | n = 333 | n = 366 |

| Formal education | 0.36 (0.18–0.75)** | 1.01 (0.44–2.36) | 1.48 (0.87–2.53) |

| Employment status | 2.42 (0.69–8.55) | 1.79 (0.38–8.43) | 0.63 (0.25–1.55) |

| Relationship status | 1.04 (0.53–2.05) | 1.11 (0.49–2.51) | 1.05 (0.62–1.78) |

| HIV awareness | |||

| Know family/friend | 1.23 (0.52–2.88) | 3.81 (1.54–9.44)** | 1.58 (0.80–3.12) |

| Know someone/not family/friend | 1.14 (0.43–3.07) | 4.31 (1.22–15.28)* | 4.53 (2.32–8.86)*** |

| HIV education | 1.90 (0.96–3.78)† | 29.69 (3.96–222.66)** | 4.53 (2.32–8.86)*** |

| HIV knowledge | 1.05 (0.91–3.45) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | 1.04 (0.86–2.51) |

| Perceived HIV risk | 1.73 (0.87–3.45) | 1.73 (0.76–3.95) | 1.47(0.86–2.51) |

The reference group for each variable is a follows: age (<25 years); formal education (less than high school); employment status (unemployed); relationship status (unstable—single/separated/divorced/widowed); HIV awareness (no/don’t know anyone); HIV education (no previous formal HIV education); perceived HIV risk (no risk); and HIV testing (no previous HIV test).

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001;

p < 0.10.

Among youths, aged <25 years, the only factor significantly associated with HIV testing was having at least a high school education, with those who have at least a high school education being less likely to report testing (OR 0.36, CI 0.18–0.75). Those who had attended an HIV forum or lecture in the previous year, compared with those who had not attended, were marginally more likely to have been tested (OR 1.90, CI 0.96–3.78).

Among younger adults, aged 25–39 years, only two of the six independent variables were significant. Those women who knew someone living with HIV/AIDS, whether family member/close friend or not, were more likely to report having been tested than were those who reported not knowing any persons living with HIV/AIDS (OR 3.81, CI 1.54–9.44 and OR 4.31, CI 1.22–15.28, respectively). Women who had attended an HIV forum/discussion in the previous year, compared with those who had not attended, were more likely to report having been tested (OR 29.69, CI 3.96–222.66). It is important to note that these extremely large ORs and CIs are a result of one or more small cells between the independent variable and dependent variable, after controlling for the remaining variables. As the p value is <0.05 and the CIs do not include one, however, this would suggest that these variables are important. In such cases, it is most appropriate to use the lower limit of the CI in describing the relationship.

Among older adults, aged ≥40, the only factor significantly associated with HIV testing was having attended an HIV forum/discussion in the previous year; compared with those who had not attended, those who attended were more likely to report having been tested (OR 4.53, CI 2.32–8.86).

DISCUSSION

First, it is important to note that the proportion of women in our study population reporting a history of HIV testing was much higher than in the Puerto Rican general population (82% vs. 40%, based on the last available testing data of the general population).51 It is possible, however, that testing among the general population has increased significantly in the last 10 years, but without supporting data we cannot make that assumption. Women in public housing have been targeted by some outreach groups here in Puerto Rico for HIV testing, which may explain the high rates of testing. Unfortunately, the act of HIV testing does not appear to significantly affect HIV protective behaviors and actually increased some risk behaviors, according to reports from the women. A belief may exist that if one tests negative, there is no need to change one’s current behavior—that there is no risk.

The women who had not been tested were asked their reason(s) for not having done so; the majority reported not perceiving themselves at risk or assuming themselves to be seronegative, which is consistent with other studies that have collected similar data.34,35,52 This finding is a disturbing indication of the reluctance of the women to acknowledge potential risk, especially when considering their admitted low level of condom use with both steady and nonsteady partners and whether engaged in vaginal or anal intercourse.

Considering that multiple partners are common among men in Puerto Rico, many women may be unknowingly putting themselves at risk because they believe themselves to be in a monogamous relationship, a belief that was extracted from focus group data from this same project. Furthermore, even among women who acknowledged that their partners may indeed see other women, there was a perception that condoms were unnecessary.

As presented earlier, hierarchical modeling was used to examine the correlates of HIV testing. The statistical results of the modeling provide insights into HIV testing among impoverished women living in public housing in Puerto Rico. Adult women aged ≥25 were much more likely to report a history of HIV testing than were women < age 25. This finding has been documented in previous research.34,35 Considering that there is an increasing incidence of HIV infection in the 15–24-year age group, it is critical to target youth in order to increase testing in this population. It is also important to target those women who are ≥40 years of age, as they report testing less than their younger adult counterparts, yet the number of reported AIDS cases among this population continues to increase. Results also revealed that HIV awareness and education were associated with increased HIV testing. Women who had attended an HIV education workshop or discussion and those who reported knowing someone who was living with HIV or had died from AIDS were more likely to report a history of HIV testing. These findings are supported by previous research showing that persons who have specific HIV knowledge and awareness are more likely to seek HIV testing. Knowing someone with HIV/AIDS may bring about more positive attitudes toward HIV testing.53,54 Increased knowledge and more positive attitudes, as well as a personal awareness of the disease, may help people to the see the benefits of HIV testing and overcome some of the barriers.

When predictors of HIV testing were examined separately by age, the predictors were significantly different. For youth, the only factor to be linked to HIV testing was formal education; surprisingly, higher levels of education were associated with a lower prevalence of HIV testing. This finding requires more exploration, as it is in apparent contradiction to a previous research study, which found that higher levels of education are associated with a greater prevalence of HIV testing in the Caribbean.15 For younger adults, HIV awareness and HIV education were both significantly associated with HIV testing in a manner similar to the unstratified model. For the older adults, only HIV education was associated with increased HIV testing. These results suggest that the age of the intended recipient must be taken into account when considering how best to target messages that promote HIV testing.

A large percentage of the women in our study have been tested for HIV, and it is imperative that appropriate HIV education and prevention messages be given to them when they receive their results. Among those who have already received their test results, only a minority reported those results to their primary sex partner. For those whose results are still pending, it is important that disclosure to all sex partners be made, especially if the results come back HIV positive. Furthermore, although many of the women in our study reported an increase in positive, safe behavior (presumably as a result of having been tested), subsequent data do not support this claim. The extremely low levels of condom use and engagement in anal intercourse with both steady and nonsteady sex partners suggest that women are still engaging in high-risk behaviors. The findings from these analyses suggest that women are unable or unwilling to accurately assess their appropriate level of risk of HIV infection; further, they indicate that HIV testing alone is insufficient to evoke positive behavioral change. It could be that the results of the test would be a better predictor; the number of self-reported HIV-positive persons prevented any statistical analyses that could examine the differences between the HIV-negative and HIV-positive women.

Although the present study has provided insight into some of the factors associated with HIV testing among impoverished women living in Puerto Rico, it is important to note that limitations of the study may impact the validity of the findings. The sample was a nonprobability sample and, as such, the generalizability of the results may be limited. In addition, the use of self-reported data may threaten internal validity. As with all surveys of sensitive issues, such data are likely to contain some bias.55

Client-initiated HIV testing to learn HIV status provided through voluntary counseling and testing remains critical to the effectiveness of HIV prevention.56 UNAIDS/WHO support the effective promotion of knowledge of HIV status among any population that may have been exposed to HIV through any mode of transmission. The CDC has launched a major new approach to HIV prevention by expanding prevention programs to include new and enhanced activities based on HIV serostatus, particularly targeting individuals with HIV, as a way to break the current steady-state of HIV transmission.57 This new initiative is called Serostatus Approach to Fighting the Epidemic (SAFE). It is aimed at those who are HIV infected, including those not aware of their status as well as those who have been tested and found to be uninfected but are at continued high behavioral risk, such as the women in the present study sample. It is unwise to underestimate the importance of being tested, nor should the present study behavioral findings negate the value of receiving appropriate counseling about the results. One of the first steps in self-protection from HIV is to be informed of one’s HIV status, which allows one to make appropriate and responsible sexual decisions.

Future success in decreasing the number of new HIV infections among women will result from targeting women who are at high risk but not because of sex work or drug use. Increasing knowledge of HIV serostatus and the implications of these results, especially among those who are infected, can serve as a gateway to sustained behavioral risk reduction interventions as well as to care and treatment. Thus, effective, culturally appropriate messages and prevention programs must to be developed and implemented; it is vital to promote universal HIV testing and appropriate counseling so that individuals may make informed sexual decisions with respect to protective sexual behaviors. It is also important to remember that the literacy level of many of these women is low, thus inhibiting the effectiveness of some brochures and printed educational materials. More innovate techniques will be required to reach these women and help them to understand the risk of their behaviors. This includes teaching them skills (such as asking a potential partner’s HIV status) and urging them to begin to use condoms with all sex partners, especially when HIV status is unknown. Considering the fact that both the actual and estimated numbers of HIV/AIDS cases among women in Puerto Rico continue to increase, it is clear that effective, targeted, and aggressive strategies are urgently needed to prevent both primary and secondary HIV transmission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the following persons: Mr. Bob Ritchie, Publications Officer, RCMI Program (Grant #2 G12 RR003050-22), Ponce School of Medicine, Ponce, Puerto Rico, for editing the manuscript; Ms. Rosa Perez, Biostatistics and Epidemiology Core, RCMI Program (Grant #2 G12 RR003050-22), for the data entry; and The Puerto Rico Comprehensive Center for HIV Disparities for funding this project (NCRR U54RR019507).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No competing financial interests exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update, December 2006. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puerto Rico Department of Health. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Puerto Rico: San Juan; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Bank. HIV/AIDS in the Caribbean: Issues and options. Human Development Sector Management Unit. Latin American and the Caribbean Region; 2000. Report number 20491-LAC. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Vol. 15. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puerto Rico Department of Health. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Puerto Rico: San Juan; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deseda CC, Sweeney PA, Woodruff BA, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus infection among women attending prenatal clinics in San Juan, Puerto Rico, from 1989–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:75. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robles RR, Matos TD, Colon HM, et al. Mortality among Hispanic drug users in Puerto Rico. PR Health Sci J. 2004;22:369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC. Revised guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral. MMWR. 2001;50:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS. UNAIDS/WHO policy statement on HIV testing. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2004. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker MH. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Thorafore, NJ: Charles B. Slack, Inc; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins DL, Galavotti C, O’Reilly K. Evidence for the effects of HIV antibody counseling and testing on risk behaviors. JAMA. 1991;266:2419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolitizki RJ, MacGowan RJ, Higgins DL, Jorgensen CM. The effects of HIV counseling and testing on risk-related practices and help-seeking behavior. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9:52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raffaelli M. Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles J Res. 2004 Mar;:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montesinos L, Preciado J. Puerto Rico. In: Francoeur RT, editor. The international encyclopedia of sexuality. IV. New York: Continuum Publishing Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pico I. Machismo y Educación. Rio Piedras: Editorial Universidad de Puerto Rico; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinmetz SK. A cross-cultural comparison of marital abuse. J Sociol Soc Welfare. 1981;8:404. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women. Baltimore: John Hopkins University School of Public Health, Population Information Program, Populations Reports; 1999. Series L, Number 11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manfrin-Ledet L, Porsche DJ. The state of science: Violence and HIV infection in women. J Assoc Nurse AIDS Care. 2003;14:56. doi: 10.1177/1055329003252056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Elliot MN, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of violence, substance use and disorder, and HIV risk behavior: A comparison of sheltered and low-income housed women in Los Angeles County. Prev Med. 2004;39:617. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sikkema KJ, Kelly JA, Winett RA, et al. Outcomes of a randomized community-level HIV prevention intervention for women living in 18 low-income housing developments. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:57. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mane P, Rao Gupta G, Weiss E. Effective communication between partners: AIDS and risk reduction for women. AIDS. 1994;8:S325. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss E, Rao Gupta G. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women; 1998. Bridging the gap: Addressing gender and sexuality in HIV prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bedimo LA, Kissinger P, Dumestre J. Psychosocial and behavioral factors associated with physical and sexual abuse among HIV-infected women; Geneva, Switzerland. International Conference on AIDS.1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinreb L, Goldberg R, Lessard D, Perloff J, Bassuk E. HIV-risk practices among homeless and low-income housed mothers. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. The need to consider characteristics of intimate partner violence when designing an intervention to increase condom use among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women; Atlanta, GA. National HIV Prevention Conference.1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saul J, Dabrowski RM, Dixon D. Negative partner reactions and sex roles: Influences on male condom use; Geneva, Switzerland. International Conference on AIDS.1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madsen J. Double jeopardy: Women, violence and HIV. Vis-à-Vis. 1996;13:1. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karon JM, Fleming PL, Steketee RW, De Cock KM. HIV in the United States at the turn of the century: An epidemic in transition. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1060. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albertyn C. Satellite symposium—Putting third first— Critical legal issues and HIV/AIDS. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand; 2000. Using rights and the law to reduce women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS: A discussion paper. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murrain M, Barker T. Investigating the relationships between economic status and HIV risk. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1997;8:416. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon PA, Hu DJ, Diaz T, Kerndt PR. Income and AIDS rates in Los Angeles County. AIDS. 1995;9:281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krueger LE, Wood RW, Diehr PH, Maxwell CL. Poverty and HIV seropositivity: The poor are more likely to be infected. AIDS. 1990;4:811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling Testing Efficacy Study Group. Voluntary HIV-1 counseling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: A randomized trail. Lancet. 2000;256:103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norman LR, Gebre Y. Prevalence and correlates of HIV testing: An analysis of university students in Jamaica. Medscape Gen Med. 2005;1:70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norman LR. HIV testing in Jamaica. HIV Med. 2006;7:231. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velez CN, Rodriguez LA, Schoenbaum E, Ungemack JA. Puerto Rican youth in drug treatment facilities: Who volunteers for HIV testing? PR Health Sci J. 1997;16:37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robles RR, Matos TD, Colon HM, et al. Effects of HIV testing and counseling on reducing HIV risk behavior among two ethnic groups. Drugs Soc. 1996;9:173. doi: 10.1300/J023v09n01_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colon HM, Robles RR, Marrero CA, et al. Behavioral effects of receiving HIV test results among injecting drug users in Puerto Rico. AIDS. 1996;10:1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.UNDP. HIV/AIDS and poverty reduction strategies. New York: United Nations Development Program; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norman LR, Carr R. The role of HIV knowledge on HIV-related behaviors: a hierarchical analysis of adults in Trinidad. Health Educ. 2003;103:145. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norman LR. Predictors of consistent condom use: A hierarchical analysis of adults from Kenya, Tanzania and Trinidad. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:584. doi: 10.1258/095646203322301022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Worthington C, Myers T. Factors underlying anxiety in HIV testing: Risk perceptions, stigma, and the patient-provider power dynamic. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:636. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013005004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Paoli MM, Manongi R, Klepp KI. Factors influencing acceptability of voluntary counseling and HIV-testing among pregnant women in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2004;16:411. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001683358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zak-Place J, Stern M. Health belief factors and dispositional optimism as predictors of STD and HIV preventive behavior. J Am Coll Health. 2004;52:229. doi: 10.3200/JACH.52.5.229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 47.CDC. Hemophilia behavioral intervention evaluation project. Atlanta, GA: CDC Behavioral Intervention Research Branch; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ministry of Health. National knowledge, attitudes and practices survey. Kingston, Jamaica: Epidemiology Unit; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 49.WHO. Definitions of indicators and targets for STI, HIV and AIDS surveillance. STI/HIV/AIDS Surveillance Rep. 2000;16:9. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention & Health Promotion; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kellerman SE, Lehman JS, Lansky AM, et al. HIV testing within at-risk populations in the United States and the reasons for seeking or avoiding HIV testing. J AIDS. 2002;31:202. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200210010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berbert B, Sumser J, Maquire BT. The impact of who you know and where you live on opinions about AIDS and health care. Soc Sci Med. 1991;2:677. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counseling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transmit Infect. 2003;79:442. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catania J, Gibson D, Chitwood D, Coates T. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: Influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:339. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.WHO. UNAIDS/WHO policy statement on HIV testing. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 57.CDC. The Serostatus Approach to Fighting the HIV Epidemic: Prevention strategies for infected individuals. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]