Summary

ERβ is regarded as a “tumor suppressor” in breast cancer due to its anti-proliferative effects. However, unlike ERα, ERβ has not been developed as a therapeutic target in breast cancer due to loss of ERβ in aggressive cancers. In a small molecule library screen for ERβ stabilizers, we identified Diptoindonesin G (Dip G) which significantly increases ERβ protein stability, while decreasing ERα protein levesl. Dip G enhances the transcription and anti-proliferative activities of ERβ, while attenuating the transcription and proliferative effects of ERα. Further investigation revealed that instead of targeting ER, Dip G targets the CHIP E3 ubiquitin ligase shared by ERα and ERβ. Thus, Dip G is a dual functional moiety that reciprocally controls ERα and ERβ protein stability and activities via an indirect mechanism. The ERβ stabilization effects of Dip G may enable the development of ERβ-targeted therapies for human breast cancers.

Keywords: breast cancer, CHIP E3 ligase, Diptoindonesin G, estrogen receptor

Introduction

ERα and ERβ, members of the steroid nuclear receptor superfamily, exhibit different biological effects, although they both mediate estrogen signaling by binding to the estrogen-response element (ERE) of target genes (Greene et al., 1986; Kuiper et al., 1996; Mosselman et al., 1996; Thomas and Gustafsson, 2011; Tremblay et al., 1997). They share 96% identity in the DNA-binding domain, but differ considerably in the ligand-binding domain (LBD) (Mosselman et al., 1996) that defines ligand subtype selectivity. Differences in ligand binding, transcriptional activation, and interactions with cofactors may account for the differential biological effects of ERα and ERβ in normal tissues, as well as in breast tumors (Bardin et al., 2004). The majority of human breast cancers express ERα along with ERβ, albeit at much lower levels (Katzenellenbogen and Frasor, 2004; Kurebayashi et al., 2000; Saji et al., 2005). Studies have shown that ERβ opposes the effects of ERα in several tissues where it decreases cell proliferation, promotes differentiation, and modulates apoptosis (Drummond and Fuller, 2010). Subtype-selective ER ligands have been developed, such as ERα-specific agonist propyl pyrazole triol (PPT) and ERβ-specific agonist diarylpropionitrile (DPN) (Meyers et al., 2001; Stauffer et al., 2000; Sun et al., 1999). ERα and ERβ accommodate various conformations upon ligand binding, and the ligands could directly impact the transcriptional activity of ERs.

Loss of ERβ (or increased ERα/ERβ ratio) is a common feature of malignant transformation detected not only in breast cancer, but also in ovarian, prostate, and colon cancers (Bardin et al., 2004). ERβ is thus often considered a “tumor suppressor”. The expression of ERα increases and ERβ decreases in early stages of breast cancer, however both receptors decline in the most invasive cancers (Fox et al., 2008). The ratio between the two receptors is important in determining differential ER signaling (Leygue et al., 1998). Moreover, the effects of estrogenic compounds on cell proliferation are dependent on the ERα/β expression ratio (Sotoca et al., 2008). ERα and ERβ are both targeted for degradation via proteasome-mediated pathways, and their degradation can be affected by levels of endogenous ligands, tumor microenvironment, the amount of chaperones, and ubiquitin ligases (Thomas and Gustafsson, 2011). These studies prompted us to identify small molecules specifically targeting the proteins that regulate ER degradation. The ultimate goal is to enhance ERβ level and activity in breast cancer cells as a means to counteract tumor cell growth.

In the present study, we performed a compound library screen for small molecules that regulate ER stability and degradation dynamics. By employing isogenic ERα and ERβ inducible cell lines (Shanle et al., 2011), we discovered a novel chemical probe, which differentially affected ER protein level and activity. Diptoindonesin G (Dip G), a naturally occurring compound first isolated from the stem barks of tropical plants (Juliawaty et al., 2009), reciprocally stabilizes ERβ and destabilizes ERα in breast cancer cells. Molecular characterization revealed that it targets CHIP ubiquitin E3 ligase to modulate ER protein stability, thus attenuating the transcriptional activity of ERα and augmenting that of ERβ. To our knowledge, Dip G represents the first small molecule that could restore the balance of ERα and ERβ via modulating the activity of CHIP E3 ligase.

Results

Dip G differentially affects ERα and ERβ protein levels

To test the hypothesis that small molecules able to stabilize ERβ protein levels and/or activate ERβ transcriptional activity will elicit anti-cancer effects in breast cancer cells, we screened a small compound library containing eighty-three compounds that were either naturally isolated from plants or insects, or chemically synthesized. To monitor the effects of compounds on ER protein levels and transcriptional activities simultaneously, we employed a previously described pair of isogenic cell lines inducibly expressing ERα or ERβ under doxycycline control and a luciferase reporter that were established in our lab (Shanle et al., 2011). The protein levels of ERα and ERβ in Hs578T-ER inducible cell lines were examined by Western blotting after compound treatment. Treatment of cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 increased both ERα and ERβ protein levels, confirming that both ER subtypes are degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome system (Fig. S1). The initial screen identified compound 57, which corresponds to Dip G, as able to increase ERβ protein levels (Fig. S1B) while decreasing ERα protein levels (Fig. S1A) in Hs578T-ERα or ERβ expressing breast cancer cells at 10 μM.

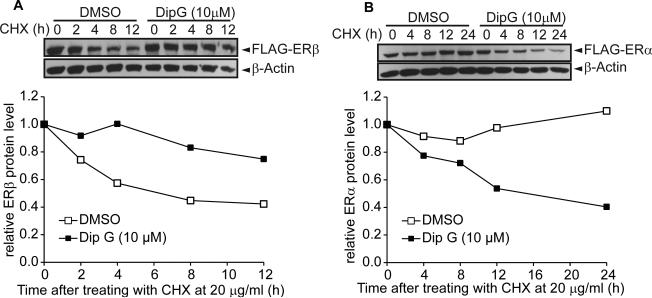

Dip G, a red amorphous powder, can be either naturally isolated from the stem bark of tropical plants Hopea mengarawan, Hopea chinensis, and Dipterocarpus alatus (Ge et al., 2010; Juliawaty et al., 2009), or synthesized (Kim and Kim, 2010). It is a resveratrol analogue, with immunosuppresive and apoptotic activity against Con A-activated T cells (Ge et al., 2010). However, there is no report of Dip G use against breast cancer. To confirm that Dip G modulates ERα and ERβ protein stability via the ubiquitin-proteasome system, we first inhibited protein synthesis using cycloheximide (CHX) and then pulse-chased the ERα and ERβ proteins in Hs578T-ER inducible breast cancer cell lines. ERβ was degraded rapidly within 12 hours of CHX treatment, whereas 10 μM Dip G treatment partially blocked degradation (Fig. 1A). In contrast, ERα protein remains stable during 24 hours of CHX treatment, and Dip G treatment enhanced degradation of ERα (Fig. 1B). Similar Dip G effects were observed in other cell lines including MDA-MB-468, MCF7, T47D, and 293T; Dip G stabilized ERβ while destabilizing ERα at a range of 1 to 10 μM (Fig. 1C-G). The Dip G-promoted ERα degradation effect was observed with endogenous ERα protein in MCF7 and T47D cells. We further optimized our western blot procedures to detect endogenous ERβ in MCF7 breast cancer cell line followed by 5 days of 10 μM Dip G treatment. We were able to observe a significant accumulation of ERβ proteins with Dip G treatment using two different antibodies against ERβ, H150 and 14C8 (Fig. 1H). The transcript level of ESR2 gene was not altered by Dip G treatment, supporting a specific posttranslational mechanism (Fig. 1I). Immunofluorescence showed that ERα and ERβ mainly localized in the nucleus regardless of Dip G treatment, suggesting that Dip G did not affect the cellular localization of the proteins (Fig. S1C and S1D). Consistent with western blotting results, we also observed enhanced ERβ staining with Dip G treatment.

Figure 1. Dip G increases ERβ protein level while decreasing ERα protein level.

Hs578T-ERαLuc (A) and Hs578T-ERβLuc inducible cells (B) were treated with 50 ng/ml doxycycline (Dox) for 24 hours. Cells were pre-treated with DMSO or 10 μM Dip G for 2 hours. Then 20 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) was added at time point 0 and cells were harvested as indicated. Western blotting analysis showed ERα or ERβ expression using anti-Flag antibody. β-actin was used as loading control. Quantification of the band intensity was performed using ImageJ software. (C) MDA-MB-468-ERβ inducible cells(Shanle et al., 2013) were treated with dox for 24 hours followed by the treatment with E2 or Dip G. (D) MCF7 cells were retro-virally infected to express Flag-ERβ followed by 24 hours of DMSO or Dip G treatment. (E) 293T cells were transfected with 3xFLAG-ERα or 3xFLAG-ERβ plasmids followed by 24 hours of DMSO or Dip G treatment. (F) MCF7 or (G) T47D cells were treated with 0, 1, or 10 μM Dip G. Western blotting showed ERα or ERβ expression using anti-Flag antibody or anti-ERα antibody. β-actin or Hsp90 was used as loading control. (H) MCF7 cells were treated with DMSO of 10 μM Dip G for 5 days. Western blotting showed ERβ protein levels using anti-14C8 and H150 antibody. Hsp90 was used as loading control. (I) Total RNA from Hs578T-ERβLuc cells was collected for qRT-PCR to examine ESR2 gene expression levels. Error bars represent ± SD values. (J) 293T cells were transfected with VT, Flag-ERβ1 or Flag-ERβcx for 24 hours followed by another 24 hours of Dip G treatment. Western blotting showed Flag-ERβ1 and Flag-ERβcx protein levels with anti-Flag antibody. β-Actin was used as loading control. See also Figure S1.

We further examined the protein level of ERβcx (ERβ2), the second ERβ isoform (Moore et al., 1998), in response to Dip G treatment. This isoform shares identical sequences with ERβ1 in exon 1-7, with exon 8 alternatively spliced to produce unique sequences (Moore et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 2008). ERβcx is frequently studied in breast cancer as it could heterodimerize with ERβ1 to enhance its transactivation in a ligand-dependent manner (Leung et al., 2006). When we transfected ERβ1 and ERβcx into 293T cells, we found that Dip G increased both isoforms protein levels (Fig. 1J).

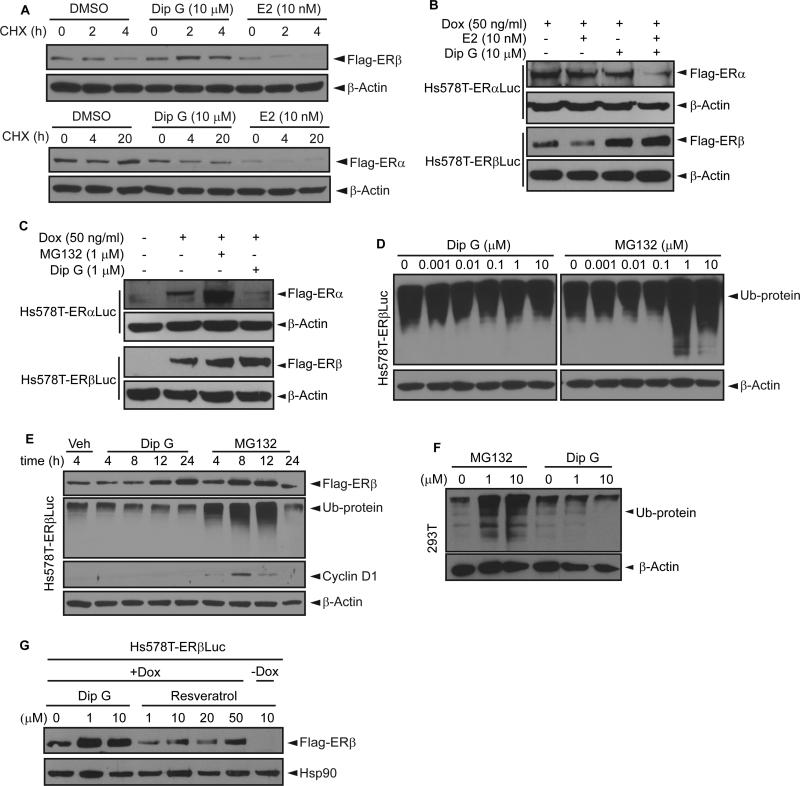

Dip G does not affect global protein degradation by the proteasome

E2 induced degradation of both ERα and ERβ by the 26S proteasome, whereas Dip G had a reverse effect on the two estrogen receptors (Fig. 2A), indicating the action of Dip G was distinct from E2. Interestingly, Dip G enhanced the degradation of ERα and blocked the degradation of ERβ when the cells were stimulated with E2 (Fig. 2B). Next, we examined whether Dip G treatment influenced global protein degradation by targeting the proteasome. MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, reduced degradation of both ERα and ERβ (Fig. 2C). While MG132 increased global protein ubiquitination in both a dose- and time-dependent manner, up to 10 μM Dip G did not increase global ubiquitination during 24 hours of treatment (Fig. 2D-E). Cyclin D1, which is known to be degraded via the ubiquitin-proteasome system pathway (Diehl et al., 1997), was used as a positive control (Fig. 2E). A similar phenomenon was observed in 293T cells where MG132 induced a robust global protein ubiquitination and Dip G did not (Fig. 2F), indicating the phenomenon was not cell line specific. Since Dip G is a resveratrol analogue (Ge et al., 2010), we also tested whether resveratrol had similar ERβ protein stabilization effects compared to Dip G. Figure 2G showed that resveratrol failed to stabilize ERβ protein up to 20 μM (Fig. 2G), suggesting that these two compounds function distinctly in regulating ERβ stability.

Figure 2. Dip G does not affect global protein degradation by proteasome.

Hs578T-ERαLuc or Hs578T-ERβLuc cells were treated with Dox to induce ER expression. (A) Both ERα and ERβ were degraded in response to E2 stimulation. (B) Dip G blocked the degradation of ERβ induced by E2 but not ERα. (C) MG132 stabilized both ERα and ERβ. (D) Cells were treated with 0 -10 μM Dip G or MG132 for 24 hours. Dip G did not cause global protein ubiquitination compared with MG132. (E) Cells were treated with Dip G or MG132 (10 μM) and harvested at the indicated time points. (F) 293T cells were treated with MG132 or Dip G. (G) Resveratrol did not increase ERβ protein levels. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-Flag, anti-Ub, anti-cyclin D1 with β-actin or Hsp90 as loading controls. See also Figure S2.

We also examined p53 and p21 protein levels after Dip G treatment. Surprisingly, Dip G also increased p21 protein levels, while p53 levels remained the same in Hs578T-ERβLuc cells (Fig. S2A). It is known that Hs578T cells express mutant p53. In MCF7 cells, Dip G decreased endogenous ERα stability and increased stability of p53 and p21 (Fig. S2B). In contrast, MG132 increased the stability of endogenous ERα, p53, and p21 proteins in MCF7 cells (Fig. S2C). The target-specific effect of Dip G compared to MG132 reinforces the possibility that Dip G may target specific protein(s) responsible for ER protein degradation.

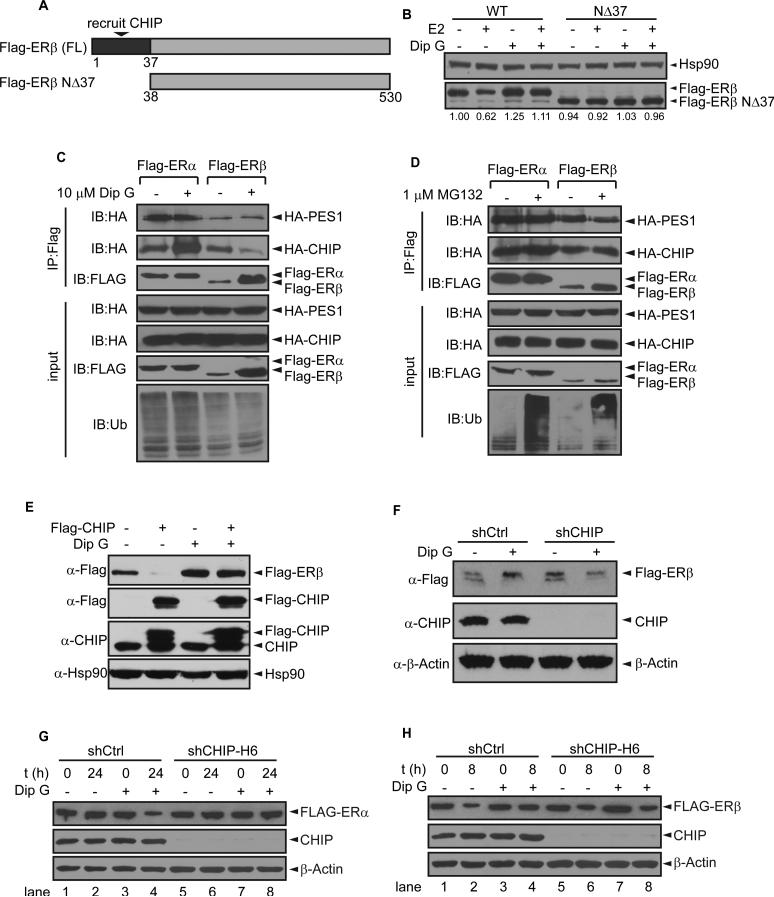

CHIP E3 ligase mediates Dip G regulated ER protein level change

To mediate the degradation process, ERα and ERβ share three common ubiquitin E3 ligases including MDM2 (Duong et al., 2007; Sanchez et al., 2013), E6AP (Li et al., 2006; Picard et al., 2008), and CHIP (carboxyl terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein) E3 ligase (Fan et al., 2005; Tateishi et al., 2004; Tateishi et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2011). Among these E3 ligases, CHIP E3 ligase is unique in that, acting in concert with a protein named PES1, it differentially regulates ER protein levels and activity in the opposite direction as does Dip G (Cheng et al., 2012). PES1 increases ERα stability, while decreasing ERβ levels in breast cancer cells (Cheng et al., 2012).

To determine which domain of ERβ is critical for Dip G-mediated ERβ protein stabilization, N- and C-terminal truncated ERβ proteins (NΔ242 and CΔ288) were expressed in 293T cells followed by Dip G treatment. When the N-terminus of ERβ was truncated, the effect of Dip G treatment was significantly diminished (Fig. S3A). In contrast, removing 288 amino acids from the ERβ C-terminus did not affect stabilization by Dip G (Fig. S3A). The N-terminal 37-amino acid-region of ERβ is necessary for the recruitment of CHIP E3 ligase to degrade ERβ via the ubiquitin-proteasome system (Tateishi et al., 2006). We further truncated this region and expressed ERβNΔ37 in 293T cells (Fig. 3A). E2 could not target ERβNΔ37 protein for degradation, consequently the stabilization effect of Dip G was not observed (Fig. 3B). This is opposite to ERβWT whose stability is decreased by E2, and E2-induced degradation of ERβWT could be reversed by Dip G treatment. As expected, E2-induced degradation of ERβWT was blocked by MG132 (Fig. S3B). These results suggest that the ubiquitin-proteasome system pathway was involved in both Dip G and MG132 regulated protein stability control. Taken together, the results revealed that the N-terminal domain of ERβ was essential for Dip G-mediated ERβ protein stabilization and CHIP E3 ligase is a likely candidate targeted by Dip G. This was consistent with our finding that Dip G stabilized the proteins of both ERβ1 and ERβcx isoforms (Fig. 1J), since they share identical structures on the N-terminal AF-1 domain (Moore et al., 1998).

Figure 3. CHIP E3 ligase is involved in Dip G regulated ERα and ERβ protein level change.

(A) Schematic diagram showed the region of ERβ that recruited CHIP E3 ligase (Tateishi et al., 2006). (B) Flag-ERβWT or Flag-ERβNΔ37 was expressed in 293T cells. Cells were pre-treated with Dip G for 2 hours and E2 was then added for another 4 hours. Quantification of the band intensity was performed with ImageJ band scan. (C) and (D) 293T cells were transfected with VT, Flag-ERα or Flag-ERβ, HA-CHIP and HA-PES1. Then, cells were treated with 10 μM Dip G for 24 hours (C) or 1 μM MG132 for 4 hours (D). Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads and Western blot was performed with anti-HA antibody to examine PES1 and CHIP co-precipitated with Flag-ERα or Flag-ERβ. (E) Vector control or Flag-CHIP, and Flag-ERβ were overexpressed in 293T cells for 24 hours. 10 μM Dip G was added to the medium for another 24 hours. The protein levels of Flag-ERβ, Flag-CHIP, and endogenous CHIP were examined by Western blot with Hsp90 as the loading control. (F) MCF7-shCtrl and MCF7-shCHIP-H6 stable cells were treated with vehicle or 10 μM Dip G for 24 hours. The protein levels of Flag-ERβ and endogenous CHIP were examined by western blot with β-actin as the loading control. (G) and (H) Endogenous CHIP E3 ligase was knocked down by shCHIP-H6 in Hs578T-ERα (G) or Hs578T-ERβ (H) inducible cells. CHX was added at t=0. Protein levels of ER were examined using anti-Flag antibody. Knockdown efficiency of CHIP was confirmed by anti-CHIP antibody. See also Figure S4 and S5. See also Figure S3.

We hypothesized that Dip G might interfere with the interaction between CHIP E3 ligase and ERs. To test this hypothesis, Flag-ERα or Flag-ERβ and CHIP and PES1 were overexpressed in 293T cells, and Flag-ER was immunoprecipitated to examine the interaction with CHIP or PES1. Dip G significantly enhanced the interaction between ERα and CHIP, while suppressing the interaction between ERβ and CHIP (Fig. 3C). As a negative control, MG132 treatment did not affect the interaction between ER and CHIP (Fig. 3D). Next, we performed overexpression or knockdown of CHIP E3 ligase in multiple cell lines to verify the role of CHIP in mediating the effects of Dip G (Fig. 3E-H). Overexpression of CHIP facilitated the degradation of ERβ and treatment by Dip G prevented CHIP-mediated degradation in 293T cells (Fig. 3E). In contrast, knockdown of CHIP abolished the stabilization of ERβ induced by Dip G in MCF7 cells (Fig. 3F). In Hs578T-ERαLuc cells, Dip G failed to induce ERα degradation when CHIP was knocked down (lane 4 and 8, Fig. 3G). In Hs578T-ERβLuc cells, Dip G failed to stabilize ERβ when CHIP was knocked down (lane 4 and 8, Fig. 3H). The results were reproducible with different independent shRNAs suggesting the effect was not due to the artifact of the single shRNA used previously (Fig. S3C-G). These results showed that CHIP E3 ligase is critical for Dip G-mediated protein stability control for both ERα and ERβ.

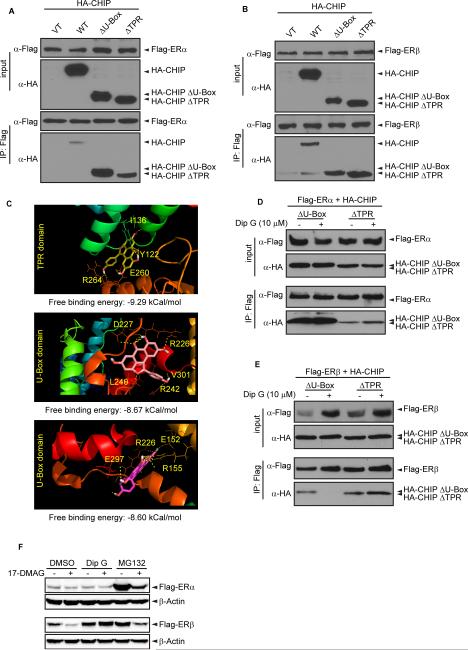

Mapping of ER-interacting domains in CHIP E3 ligase and docking of Dip G to CHIP

The carboxyl terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein, CHIP, is an Hsc70-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase that promotes protein degradation by the 26S proteasome (Jiang et al., 2001). The N-terminal TPR domain interacts with Hsc70 or Hsp90, whereas the C-terminal U-Box domain confers E3 ligase activity (Jiang et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2005). The protein forms an asymmetric homodimer and the U-Box domain forms the dimer interface (Zhang et al., 2005). To determine which domain of CHIP was required for the interaction with ER, wild type (WT) CHIP or truncated proteins were expressed in 293T cells and immunoprecipitated with Flag-ERα or Flag-ERβ. Both TPR (tetratricopeptide repeat) and U-Box domain could individually interact with ER (Fig. 4A, 4B). Next, we modeled Dip G binding to CHIP E3 ligase by in silico molecular docking. Molecular docking showed that both the TPR and the U-Box domains interact with Dip G with high affinity, with a free binding energy between −9.0 ~ −8.0 kCal/mol. The contacting residues between the protein and the ligand are highlighted in Fig. 4C. To pinpoint which domain of CHIP is essential for the opposite regulation of ER stability in the presence of Dip G, truncated CHIP proteins were immunoprecipitated with Flag-ERα or Flag-ERβ after Dip G treatment in 293T cells. Dip G mildly enhanced the interaction between ERα and CHIP-ΔTPR (Fig. 4D), while strongly suppressing that between ERβ and CHIP-ΔU-Box (Fig. 4E), suggesting that Dip G may target different interfaces of CHIP to regulate ER stability. The TPR domain of CHIP which interacts with Hsp90 represents a critical region modulating the stability of ERβ (Fig. 4E). We have previously shown that 17-DMAG, the Hsp90 inhibitor, was able to down-regulate the protein levels of ER and Hsp90 was critical for the transcriptional activity of the ERβ (Powell et al., 2010). Hsp90 interacts with large portions of ER LBD and sequences of the receptor required for stable DNA binding (Chambraud et al., 1990). 17-DMAG inhibited the function of Hsp90, thus decreasing the protein levels of ER (Rastelli et al., 2005; Schulte et al., 1998). Since CHIP is a co-chaperone of Hsp90 for protein degradation and folding (Dickey et al., 2007; McDonough and Patterson, 2003), and CHIP interacts with the N-terminal AF-1 domain of ERβ (Tateishi et al., 2006), it is very likely that CHIP, Hsp90 and ERβ form a ternary complex. We further investigated the role of Hsp90 using its inhibitor, 17-DMAG. While 17-DMAG destabilized ERβ, Dip G counteracted the effect of Hsp90 inhibitor 17-DMAG and blocked the protein level decrease (Fig. 4F). MG132 could not prevent ERβ degradation when cells were stimulated with 17-DMAG (Fig. 4F). This result further demonstrated distinct ERβ stabilization mechanisms for Dip G and MG132.

Figure 4. Mapping of ER interacting domains in CHIP E3 ligase and molecular docking of Dip G to CHIP.

(A) ERα and (B) ERβ bind to both the U-Box and TPR domain of CHIP. 293T cells were transfected with VT, WT, ΔU-Box or ΔTPR of HA-CHIP E3 ligase with (A) Flag-ERα or (B) Flag-ERβ. Immunoprecipitation was performed using M2 beads to pull down Flag-ER. The immunoprecipitated CHIP was examined with anti-HA antibody. (C) The ligand Dip G and the receptor CHIP E3 ligase (PDB code: 2C2L) (Zhang et al., 2005) were prepared with SYBYL; and blind docking was performed using PyMOL and autodock4.2. Three best-energy results of blind docking CHIP E3 ligase in complex with Dip G were shown including the TPR domain and the U-box domain of CHIP. The free binding energy was calculated and shown below each diagram. (D) and (E) 293T cells were transfected with ΔU-Box or ΔTPR of HA-CHIP E3 ligase with (D) Flag-ERα or (E) Flag-ERβ. 24 hours after transfection, 10 μM Dip G was added for another 24 hours. Immunoprecipitation was performed using M2 beads to pull down Flag-ER. The immunoprecipitated truncated CHIP proteins were examined with anti-HA antibody. (F) Hs578T-ER inducible cells were treated with DMSO, 10 μM Dip G, or 1 μM MG132 for 24 hours in the presence or absence of 250 nM 17-DMAG. Flag-ERα and ERβ protein levels were examined by Western blotting with β-actin as the loading control.

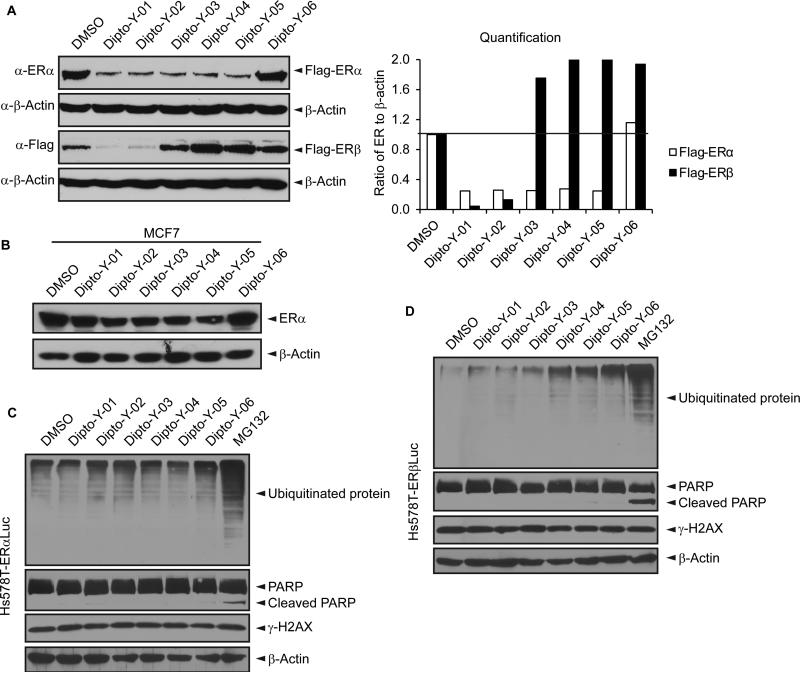

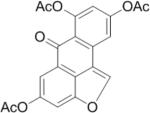

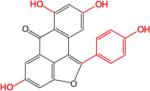

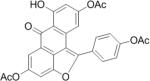

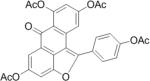

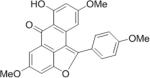

The structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis of Dip G

SAR analysis was carried out to investigate the structural properties of Dip G. Six analogues including Dip G were compared (chemical structures are shown in Table 1) for ER stability control (Dip G is Dipto-Y-03). Data and copies of spectra for Dipto-Y-03 and 06 were reported previously (Kim and Kim, 2010). The NMR data of the other analogues were shown in Fig. S4. In both Hs578T and MCF7 cells, Dipto-Y-01 – Y-05 caused ERα protein destabilization (Fig. 5A, 5B). Dipto-Y-03 – Y-06 significantly increased ERβ protein stability whereas Dipto-Y-01 and 02 decreased ERβ stability (Fig. 5A). Based on the SAR analysis, the rotatable phenol group on Dip G seemed to be critical in determining the activity of Dip G; the hydroxyl groups appear to contribute to the solubility of compounds in cell culture and DMSO (features highlighted in red). Moreover, these analogues did not induce significant global protein ubiquitination compared with MG132, nor did they cause apoptosis as shown by the cleaved PARP (Poly ADP ribose polymerase) levels or DNA damage as indicated by γ-HA2X levels (Fig. 5C, D).

Table I. Dip G analogues.

The chemical structure, molecular weight and solubility in DMSO are shown.

| Compound | Structure | Molecular weight | Solubility in DMSO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dipto-Y-01 |

|

352.29 | ~ 10 mM |

| Dipto-Y-02 |

|

396.35 | ~ 20 mM |

| Dipto-Y-03 (Dip G) |

|

360.32 | > 100 mM |

| Dipto-Y-04 |

|

486.43 | < 10 mM |

| Dipto-Y-05 |

|

528.46 | < 10 mM |

| Dipto-Y-06 |

|

402.4 | < 10 mM |

Table I. Chemical Structure, Molecular Weight and Solubility of Dip G Analogues.

Figure 5. The structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis of Dip G.

(A) The activity of Dip G analogues was examined after 24 hours of treatment (10 μM) in Hs578T-ER inducible cells (Dipto-Y-03 = Dip G). Quantification of band intensity was performed with ImageJ. (B) Endogenous ERα protein levels were examined after 24 hours of 10 μM Dip G analogues treatment in MCF7 cells. (C) and (D) Total ubiquitination, PARP, p21, and γ-H2AX were examined in Hs578T-ERα (C) or Hs578T-ERβ (D) by Western blot analysis after cells were treated with 10 μM Dip G analogues with MG132 as a positive control. See also Figure S4.

Dip G differentially affects ERα and ERβ activity in breast cancer cells

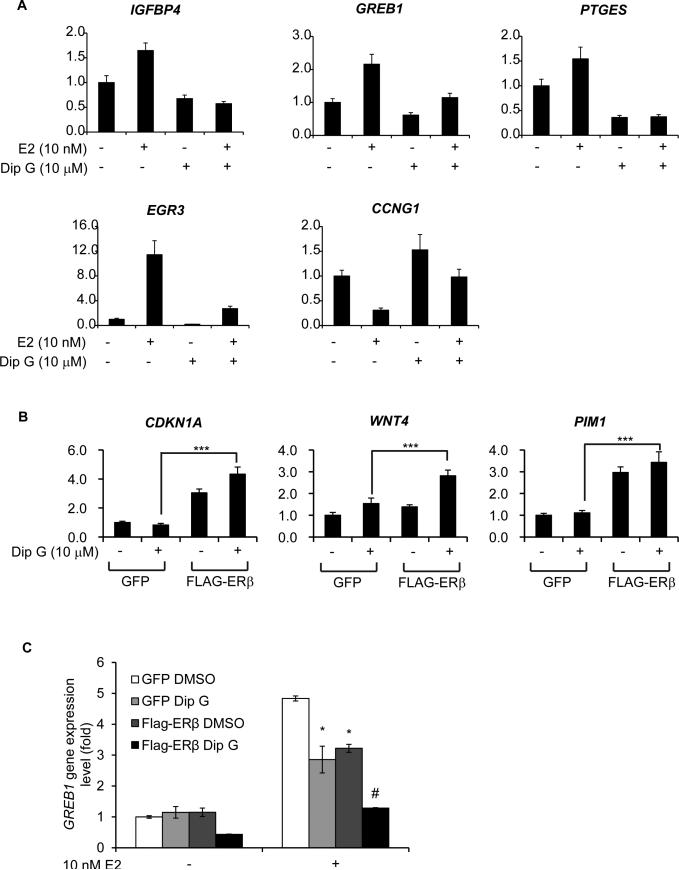

In addition to altered protein levels, we examined whether Dip G affected ER transcriptional activity and altered ER target gene expression. Dip G strongly inhibited ERα-mediated E2 signaling in MCF7 cells as shown by IGFBP4, GREB1, PTGES, EGR3, and CCNG1 gene expression levels after 24 hours of treatment (Fig. 6A). In fact, the ERα target gene expression in response to E2 stimulation was suppressed by Dip G after 4 hour-treatment (Fig. S5A), whereas the protein level remained the same at 4 hours (Fig. S5B). This result indicated that the ERα activity downregulation was not totally due to the protein destabilization. Conversely, Dip G increased ERβ ligand-independent activity as shown by CDKN1A, WNT4, and PIM1 gene expression in MDA-MB-468 cells (Fig. 6B) (Shanle et al., 2013). In MCF7 cells, Dip G alone did not affect the GREB1 gene expression in GFP expressing cells, but it inhibited E2-induced GREB1 expression 40% compared with E2 treatment alone (Fig. 6C). Expression of ERβ did not affect GREB1 gene expression, but it decreased E2-induced GREB1 expression to the similar level as Dip G treatment alone (Fig. 6C). In the presence of ERβ, Dip G significantly reduced GREB1 gene expression and inhibited E2 signaling (Fig. 6C), suggesting that Dip G augments the transcriptional activity of ERβ. Similarly, in the 293T luciferase reporter assay, Dip G alone did not affect the transcriptional activity of ERα or ERβ (Fig. S5C, D), but Dip G repressed the transcriptional activity of ERα at 1 μM and enhanced the activity of ERβ at 10 μM in the presence of low concentrations of E2 (Fig. S5E, F). 10 μM Dip G did not show further enhanced transcriptional repression in 293T-ERαERE cells probably due to the limited intake of Dip G from the medium by the cells resulted from enhanced cytotoxicity with higher concentration of Dip G treatment (Fig. S5E).

Figure 6. Dip G differentially affects ERα- and ERβ-mediated gene expression.

(A) MCF7 cells were cultured in stripped media for 3 days. After pre-treatment of 10 μM Dip G for 2 hours, 10 nM E2 was added for another 24 hours. Total RNA was collected for qRT-PCR to examine the relative expression of ERα target genes including IGFPB4, GREB1, PTGES, EGR3, and CCNG1. (B) and (C) MDA-MB-468 or MCF7 cells were infected with retroviruses expressing GFP or Flag-ERβ and stable cells were generated with one week of G418 selection. (B) Vehicle control or 10 μM Dip G were added to MDA-MB-468 cells for 24 hours. Total RNA was collected for qRT-PCR to examine the relative expression of ERβ target genes changes including CDKN1A, WNT4, and PIM1. (C) MCF7 cells were pre-treated with 10 μM Dip G for 24 hours followed by 4 hours of treatment with 10 nM E2. Total RNA was collected for qRT-PCR to examine the relative expression of GREB1. The error bars represent ± SD values. The ‘#’ symbol indicates the statistical significance compared with “Flag-ERβ DMSO”. See also Figure S5.

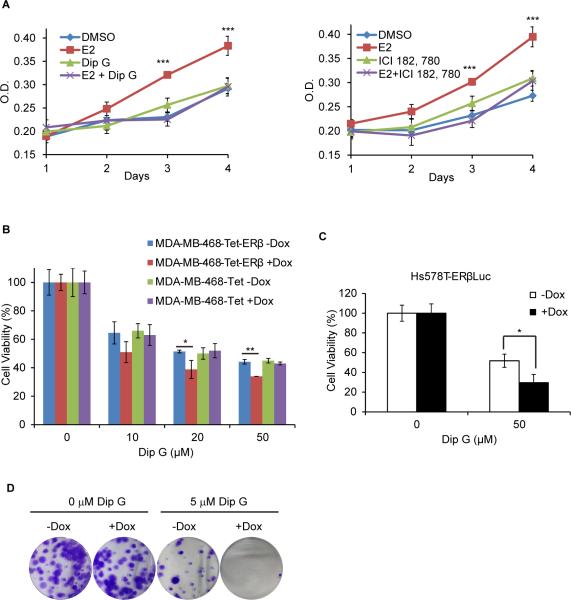

In accordance with the ERα destabilization effects of Dip G, Dip G inhibited E2-induced cell proliferation in MCF7 cells to a similar extent as ICI 182,780, which is an ER antagonist (Fig. 7A). We also performed the cell counting experiments with combination treatment of E2, tamoxifen and Dip G in MCF7 cells. As expected, tamoxifen treatment inhibited E2-induced cell proliferation (Fig. 7B). When Dip G was added, the inhibitory effect was further augmented (Fig. 7B). This result demonstrated that Dip G and tamoxifen may target ERα via different mechanisms to decrease its activity. MDA-MB-468-ERβ-inducible cells were used (Shanle et al., 2013) to examine whether Dip G could potentiate the anti-proliferative effects of ERβ. As a negative control, parental cell line MDA-MB-468-Tet cells were treated with Dip G in the presence or absence of Dox. Figure 7C showed that Dip G treatment decreased cell viability (40%-50%) at multiple concentrations (10-50 μM). Although Dip G alone had anti-proliferative effects, Dox treatment did not interfere with Dip G action in MDA-MB-468-Tet cells. This is in contrast to MDA-MB-468-ERβ-inducible cells where treatment with Dip G alone decreased cell viability in the absence of ERβ expression, and the inhibitory effect of Dip G was augmented by the induction of ERβ (Fig. 7C). Similar results were obtained with Hs578T-ERβ inducible cells where Dip G treatment augmented the growth inhibitory effect of ERβ (Fig. 7D). Finally, in Hs578T-ERβ cells, ERβ expression alone (+Dox) did not significantly affect colony formation. Dip G treatment alone greatly inhibited colony formation, and this effect was further magnified by the expression of ERβ (Fig. 7E). Together, our results suggest that Dip G enhances the transcriptional activity and potentiates the growth inhibitory effects of ERβ while attenuating the transcription and proliferative activities of ERα.

Figure 7. Dip G inhibits E2-induced cell proliferation while augmenting the growth inhibitory effect of ERβ.

(A) MCF7 cells were cultured in stripped media for 3 days. Cells were treated with 10 μM Dip G or 100 nM ICI 182,780 in the presence or absence of 10 nM E2, and the media was changed every two days. Cell proliferation was measured by MTT assay. (B) MCF7 cells were cultured in stripped media for 3 days. Cells were treated with DMSO, 10 nM E2, 100 nM Tamoxifen, 10 μM Dip G or in combination, and the media was changed every two days. Cell proliferation was measured by cell counting. (C) MDA-MB-468 cells or (D) Hs578T-ERβLuc cells were cultured in stripped media for 3 days. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5,000 cells/well with Dox treatment. 24 hours later, cells were treated with indicated concentrations of Dip G. MTT assay was performed after 5 days of treatment. (E) Hs578T-ERβLuc cells were cultured in normal media. Cells were treated with 50 ng/ml Dox for 24 hours. Dip G (0 or 5 μM) was added and media was changed every four days. Colony formation assay was performed after two weeks of treatment. Experiments were performed in duplicate. See also Figure S6.

Indeed, we also observed pleiotropic effects of Dip G on cell cycle progression as a reflection of proliferation in the absence of ERβ. First, in MCF7 cells, Flag-ERβ expression did not affect cell proliferation and cell cycle progression (Fig. S6A). Treatment of Dip G at 10 μM effectively arrested the cells at G2/M cell cycle phase (Fig. S6A). Second, in Hs578T-ERβ inducible cells, Dip G arrested the cells at S phase in the absence of ERβ. While ERβ strongly induced G1/S phase arrest, Dip G further enhanced the arrest as shown by the quantification (Fig. S6B). It is likely that Dip G may also target different cell cycle regulators in specific cell lines to inhibit cell proliferation through cell cycle arrest.

It has been shown that ERβ suppresses epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) by various mechanisms (Mak et al., 2010; Samanta et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2012). In basal-like breast cancer cells, ERβ represses the EGFR signaling at both RNA and protein levels, leading to the repression of EMT (Samanta et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2012). In prostate cancer cells, ERβ impedes EMT by destabilizing HIF-1α (Mak et al., 2010). We further investigated whether Dip G would inhibit EMT by examining the EMT biomarker gene expression. In LM2 cells, knockdown of ESR2 gene upregulated the gene expression of FN and TAGLN, two genes that are known to be upregulated during EMT (Fig. S6C). We found that 3 days of 10 μM Dip G treatment significantly down-regulated FN and TAGLN mRNA levels while up-regulating CDH1 and CDKN1A mRNA levels in LM2 cells (Fig. S6D). The result suggested that Dip G impeded EMT and invasion of breast cancer cells.

Discussion

Among primary breast cancers, ~70% express ERα, 59% co-express ERα and ERβ, and 17% express ERβ only (Leygue and Murphy, 2013). Because ERα is expressed in over 70% of all breast cancers, endocrine therapies targeting ERα have become a mainstay of breast cancer treatment. For example, tamoxifen is used to inhibit ERα transcriptional activity and fulvestrant is used to degrade ERα protein. In breast cancer, ERβ decreases cell proliferation, promotes differentiation, and modulates apoptosis (Drummond and Fuller, 2010). Moreover, ERβ protein levels decrease as tumors progress. Thus, ERβ is regarded as a “tumor suppressor” for breast tissue and stabilizing ERβ protein may be a prerequisite for designing ERβ-based breast cancer therapy. Transcriptional silencing and ERβ degradation result in the overall loss of ERβ during breast cancer progression (Cheng et al., 2012; Rody et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2003). However, the control of ERβ stability remains elusive.

Efforts have been made to identify dual-functional small molecules that reciprocally regulate ERα and ERβ transcriptional activity, ideally both an ERα antagonist and an ERβ agonist for breast cancer therapy. As THC has been reported to act as an ERα agonist and an ERβ antagonist (Shiau et al., 2002), this compound was not pursued in cancer treatment. In seeking small molecules that could restore ERβ expression level in breast cancer cells, we identified a dual-functional small molecule, Dip G, which enhanced ERβ function and inhibited ERα function (Fig. 6, 7), as reflected by stabilizing ERβ protein and destabilizing ERα protein, respectively. Interestingly, Dip G did not bind to the ligand-binding pocket of ERα or ERβ as examined by the fluorescent polarization ligand-binding assay (data not shown). The crystal structures for the N-terminal AF-1 domains of ERα and ERβ have not been determined, however, they are essential for stability and the ligand-independent activity control of both ERs (Picard et al., 2008; Tremblay et al., 1999). We cannot exclude the possibility that Dip G may directly bind to the N-terminal AF-1 domain of ERα or ERβ, and interfere with the interaction with CHIP. Nevertheless, we were able to dock Dip G to CHIP crystal structures (Fig. 4C). A comprehensive mutagenesis study could pinpoint key residues on CHIP that determine Dip G-mediated ERβ stabilization and ERα de-stabilization effects. Since both TPR and U-box domains of CHIP interact with ERα and ERβ (Fig. 4A-B) and Dip G could be docked to both domains (Fig. 4C), we speculate that Dip G-bound TPR and U-Box domains might differentially interact with ERα and ERβ to determine the fate of the proteins.

A number of proteins have been reported to regulate ERβ stability. CHIP, E6AP, and MDM2 are known ubiquitin E3 ligases targeting ERβ for degradation (Cheng et al., 2012; Picard et al., 2008; Sanchez et al., 2013; Tateishi et al., 2006). Ubc9 promotes ERβ sumoylation by attaching SUMO-1 (Picard et al., 2012). In addition, PES1 and SUG1 may regulate ERβ degradation via indirect mechanisms (Cheng et al., 2012; Masuyama and Hiramatsu, 2004). Specific E3 ligases target unique sites or domains on ERβ to regulate its degradation. Asp-236 and Glu-237 on the hinge region of ERβ are critical for ERβ turnover by the Akt pathway (Sanchez et al., 2013). Moreover, phosphorylation of Ser-94 and 106 within the ERβ AF-1 domain by Mek1/Erk is critical for E6AP-mediated degradation (Picard et al., 2008). For CHIP, the N-terminal 37-amino acid-region of ERβ is necessary to recruit E3 ligase, while the ERβ F-domain suppresses proteolysis (Tateishi et al., 2006). CHIP appears to be an important effector of Dip G-mediated ER stability control. When CHIP was knocked down, Dip G treatment failed to stabilize ERβ and decrease ERα (Fig. 3G, H). The role of CHIP is further supported by the docking of Dip G to both TPR and U-box domains of CHIP (Fig. 4C) and the differential regulation of Dip G by targeting the two separate domains of CHIP (Fig. 4D,E). We cannot exclude the possibility that Dip G may have other cellular targets in breast cancer cells also playing a role in stability regulation of ERs and mediating cytotoxicity of Dip G (Fig. 7). It will be important to synthesize biotinylated Dip G analogue and employ an unbiased proteomics approach to immunoprecipitate proteins interacting with Dip G and identify additional effector proteins engaged in ERβ stability control. To facilitate this, we performed SAR analysis of Dip G (Fig. 5). Our analysis indicated the far hydroxyl group in the phenol of Dip G is dispensable for Dip G function and thus might be conjugated with biotin.

CHIP E3 ligase has been shown to participate in degradation of various proteins including ERα and ERβ (Tateishi et al., 2004; Tateishi et al., 2006), p53 (Esser et al., 2005), Hsc70 (Jiang et al., 2001), glucocorticoid receptor (Connell et al., 2001), ErbB2 (Xu et al., 2002), HIF1α (Luo et al., 2010), and SRC-3 (Kajiro et al., 2009). We found that Dip G treatment also stabilized p53 and p21 proteins in MCF7 cells (Fig. S2), consistent with the model that Dip G-CHIP interaction indirectly regulates ER stability. In addition to its function as an ubiquitin ligase, CHIP also possesses an intrinsic chaperone activity, regulating the balance between protein folding and degradation for chaperone substrates (Connell et al., 2001; Rosser et al., 2007). However, the role of CHIP in tumorigenesis is controversial: while it promotes tumor proliferation and invasion in glioma, gallbladder carcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, it also suppresses tumor progression in breast cancer, gastric cancer and prostate cancer (Kajiro et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2014). No small molecule CHIP modulators have been reported so far, and we are the first to identify Dip G as a novel CHIP modulator in breast cancer cells, which will significantly contribute to the study of CHIP functions in different disease models. Dimerization of CHIP via the U-Box domain is a unique feature and is essential for its activity (Nikolay et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005). It is also important to determine whether Dip G affects the dimerization of CHIP to alter its activity towards different substrates.

Selective antagonists for ERα and agonists for ERβ have been shown to inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer cells. However, ERβ protein is detected at low levels in breast cancer cells, impeding the application of ERβ agonists in breast cancer therapy. Endoxifen, the most important tamoxifen metabolite, could target ERα for degradation while stabilizing ERβ in breast cancer cells (Wu et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2011). Although the degradation mechanism is not yet clear, endoxifen seems to directly bind ER and induce ERα/β heterodimerization (Wu et al., 2011). Our lab had previously shown that ERα/β heterodimers elicit anti-proliferative effects in breast cancer cells (Powell et al., 2012). Dip G does not increase ERα/β heterodimerization (data not shown), which is consistent with a failure to detect binding of Dip G to ERs. These results implicate a distinct mode of action for Dip G compared to endoxifen. The increased ERα/β expression ratio is frequently observed during the development and progression of hormone-sensitive cancers, influencing response of cancer to systematic therapy (Thomas and Gustafsson, 2011). We had previously proposed to increase ERβ/ERα ratio and induce their heterodimerization as an alternative means for endocrine therapy (Powell and Xu, 2008). However, this method will not be effective unless ERβ levels can be elevated. The discovery of Dip G supports the feasibility of rebalancing ER levels in cancer cells, which will enable the combined treatment of Dip G with the ERα/β heterodimer inducers. In addition, ERβ stabilizing molecules such as Dip G may be combined with the ERβ selective ligands to constitute a new therapeutic regimen to target ERβ in human breast cancers.

Significance

Unlike ERα which promotes breast cancer growth in over 70% of all human breast cancers, ERβ is regarded as a “tumor suppressor” due to its growth inhibitory effects on breast tumor in vitro and in vivo and its decreased expression in aggressive breast cancers. Therefore, it is imperative to understand control of ERβ protein stability to restore its expression. An elevated ERα/ERβ ratio has been shown in numerous studies to promote breast cancer progression. Ideally, small molecule probes that could counteract elevated ERα/ERβ ratios would allow the design of alternative treatments for breast cancer patients. We discovered that Dip G, a naturally occurring, dual-function, small molecule, increases ERβ protein levels while decreasing ERα protein levels in multiple breast cancer cell lines. We have also characterized the mechanism of Dip G regulation of ER protein levels as targeting an ubiquitin E3 ligase CHIP that is shared between ERα and ERβ. To our knowledge, Dip G is the first naturally occurring compound that reciprocally controls ERα and ERβ stability and activity. Dip G may be developed as a new class of Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERMs) for the treatment of human breast cancer.

Experimental Procedures

Cell culture

All of the cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). LM2 cell line is a kind gift from Dr. Joan Massagué (Minn et al., 2005). 293T, MCF7, LM2 and MDA-MB-468 cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) at 37° with 5% CO2. T47D cell line was maintained in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS. Hs578T-ERαLuc and Hs578T-ERβLuc inducible cell lines (Shanle et al., 2011) were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% Tet-approved FBS (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). To induce ERα or ERβ expression, cells were treated with 50 ng/ml doxycycline (Clontech) for 24 hours. For the cycloheximide (CHX) chase experiment, cells were pretreated with Dip G at various concentrations. 20 μg/ml CHX (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was then added for the indicated times before harvesting the cells.

Compounds and reagents

E2, ICI 182,780, MG132, Resveratrol, and 17-DMAG were purchased from Sigma. Dip G was isolated as reported previously (Ge et al., 2010). Dip G analogues (Dipto-Y-01 to Dipto-Y-06) were synthesized as previously described (Kim and Kim, 2010). Transfection reagent TranIT-LT1 was purchased from Mirus (Madison, WI).

Virus packaging, infection and stable cell line generation

Retroviruses and lentiviruses were packaged as previously described (Zhao et al., 2014). To generate stable cell lines, cells were selected for a week with 800 μg/ml G418 (RPI, Mount Prospect, IL) for Flag-ERβ overexpression or with 2 μg/ml puromycin (RPI) for CHIP E3 ligase and ERβ knockdown.

Immunofluorescence and Immunoprecipitation

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2014). For immunoprecipitation, 293T cells were lysed in Triton X-100 lysis buffer (50mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitors and benzonase). After centrifugation at 13,000 g for 10 min, the supernatants (1 mg total protein) were collected and incubated with anti-Flag M2 affinity gel at 4°C for 2 h with rotation. Samples were washed with lysis buffer four times, and incubated with competitive 3xFlag peptides for 15 min with vigorous agitation. Proteins were resuspended in 5x SDS sample loading buffer, heated to 95°C for 5 min, and subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (Zhao et al., 2013). Anti-FLAG and β-Actin antibodies were purchased from Sigma. Antibodies against CHIP E3 ligase, ERα, ERβ (H150), HA, ubiquitin, and Hsp90 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-PARP and γ-H2AX antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Denvers, MA). Anti-p53 and p21 antibodies were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Antibody against ERβ (14C8) was purchased from GeneTex (Irvine, CA).

To detect the endogenous ERβ, the procedures were optimized as follows: cells were lysed with triton lysis buffer containing 1% SDS and then subject to sonication before centrifugation. 50 μg of protein was resolved SDS-PAGE. The immunoblots were visualized using Luminata Crescendo Western HRP substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA) on autoradiography film.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was measured by MTT assay as previous described (Zhao et al., 2013).

2-D Colony formation assay

Colony formation assay was performed as previously described (Noetzel et al., 2012). Hs578T cells were seeded at 200 cells/well in 6-well plates and 5 μM Dip G was replaced every four days for two weeks. Cells were then fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.05% crystal violet.

Quantitative real time-PCR

qRT-PCR was performed as previously described (Zhao et al., 2013). Primers sequences (IDT, Coralville, IA) used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase assays were performed as previously described (Shanle et al., 2011).

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed as previously described (Zhao et al., 2013). Before compound treatment, cells were synchronized at G0/G1 cell cycle phase by serum starvation (DMEM only) for 24 hours. Cells were then recovered with normal media containing DMSO or 10 μM Dip G for 16 hours (MCF7) or 24 hours (Hs578T-ERβERELuc).

Molecular docking

The crystal structure of CHIP E3 ligase was retrieved from Protein Data Bank (PDB code: 2C2L) (Zhang et al., 2005). The ligand Dip G and the receptor CHIP E3 ligase were prepared with SYBYL and blind docking was performed using PyMOL and autodock4.2.

Statistical analysis

All results are representative of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using a two-sided Student t-test. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kenneth Satyshur for the molecular docking of CHIP E3 ligase and Dip G, and Dr. Gregg L. Semenza for providing the CHIP ΔU-Box and ΔTPR plasmids. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Richard R. Burgess for critical review of the manuscript. This project is supported by DOD ERA of HOPE Scholar Award (W81XWYH-11-1-0237) to W.X. The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Z.Z. and L.W. performed and analyzed experiments. Y.J. and I.K. provided Dip G and its analogues for SAR analysis. R.T. provided Dip G and compound library for initial screening. Z.Z., L.W., and W.X. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Bardin A, Boulle N, Lazennec G, Vignon F, Pujol P. Loss of ERbeta expression as a common step in estrogen-dependent tumor progression. Endocrine-related cancer. 2004;11:537–551. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambraud B, Berry M, Redeuilh G, Chambon P, Baulieu EE. Several Regions of Human Estrogen-Receptor Are Involved in the Formation of Receptor-Heat Shock Protein-90 Complexes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:20686–20691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Li J, Han Y, Lin J, Niu C, Zhou Z, Yuan B, Huang K, Li J, Jiang K, et al. PES1 promotes breast cancer by differentially regulating ERalpha and ERbeta. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:2857–2870. doi: 10.1172/JCI62676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell P, Ballinger CA, Jiang J, Wu Y, Thompson LJ, Hohfeld J, Patterson C. The co-chaperone CHIP regulates protein triage decisions mediated by heat-shock proteins. Nature cell biology. 2001;3:93–96. doi: 10.1038/35050618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey CA, Kamal A, Lundgren K, Klosak N, Bailey RM, Dunmore J, Ash P, Shoraka S, Zlatkovic J, Eckman CB, et al. The high-affinity HSP90-CHIP complex recognizes and selectively degrades phosphorylated tau client proteins. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:648–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI29715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl JA, Zindy F, Sherr CJ. Inhibition of cyclin D1 phosphorylation on threonine-286 prevents its rapid degradation via the ubiquitinproteasome pathway. Genes & development. 1997;11:957–972. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AE, Fuller PJ. The importance of ERbeta signalling in the ovary. The Journal of endocrinology. 2010;205:15–23. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong V, Boulle N, Daujat S, Chauvet J, Bonnet S, Neel H, Cavailles V. Differential regulation of estrogen receptor alpha turnover and transactivation by Mdm2 and stress-inducing agents. Cancer research. 2007;67:5513–5521. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser C, Scheffner M, Hohfeld J. The chaperone-associated ubiquitin ligase CHIP is able to target p53 for proteasomal degradation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:27443–27448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M, Park A, Nephew KP. CHIP (carboxyl terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein) promotes basal and geldanamycin-induced degradation of estrogen receptor-alpha. Molecular endocrinology. 2005;19:2901–2914. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox EM, Davis RJ, Shupnik MA. ERbeta in breast cancer--onlooker, passive player, or active protector? Steroids. 2008;73:1039–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge HM, Yang WH, Shen Y, Jiang N, Guo ZK, Luo Q, Xu Q, Ma J, Tan RX. Immunosuppressive resveratrol aneuploids from Hopea chinensis. Chemistry - a European Journal. 2010;16:6338–6345. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene GL, Gilna P, Waterfield M, Baker A, Hort Y, Shine J. Sequence and expression of human estrogen receptor complementary DNA. Science. 1986;231:1150–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.3753802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Ballinger CA, Wu Y, Dai Q, Cyr DM, Hohfeld J, Patterson C. CHIP is a U-box-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase: identification of Hsc70 as a target for ubiquitylation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:42938–42944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliawaty LD, Sahidin, Hakim EH, Achmad SA, Syah YM, Latip J, Said IM. A 2-arylbenzofuran derivative from Hopea mengarawan. Natural product communications. 2009;4:947–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiro M, Hirota R, Nakajima Y, Kawanowa K, So-ma K, Ito I, Yamaguchi Y, Ohie SH, Kobayashi Y, Seino Y, et al. The ubiquitin ligase CHIP acts as an upstream regulator of oncogenic pathways. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:312–319. doi: 10.1038/ncb1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenellenbogen BS, Frasor J. Therapeutic targeting in the estrogen receptor hormonal pathway. Seminars in oncology. 2004;31:28–38. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Kim I. Total synthesis of diptoindonesin G via a highly efficient domino cyclodehydration/intramolecular Friedel-Crafts acylation/regioselective demethylation sequence. Organic letters. 2010;12:5314–5317. doi: 10.1021/ol102322g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurebayashi J, Otsuki T, Kunisue H, Tanaka K, Yamamoto S, Sonoo H. Expression levels of estrogen receptor-alpha, estrogen receptor-beta, coactivators, and corepressors in breast cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2000;6:512–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung YK, Mak P, Hassan S, Ho SM. Estrogen receptor (ER)-beta isoforms: a key to understanding ER-beta signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:13162–13167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leygue E, Dotzlaw H, Watson PH, Murphy LC. Altered estrogen receptor alpha and beta messenger RNA expression during human breast tumorigenesis. Cancer research. 1998;58:3197–3201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leygue E, Murphy LC. A bi-faceted role of estrogen receptor beta in breast cancer. Endocrine-related cancer. 2013;20:R127–139. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Li Z, Howley PM, Sacks DB. E6AP and calmodulin reciprocally regulate estrogen receptor stability. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:1978–1985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Zhong J, Chang R, Hu H, Pandey A, Semenza GL. Hsp70 and CHIP selectively mediate ubiquitination and degradation of hypoxiainducible factor (HIF)-1alpha but Not HIF-2alpha. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:3651–3663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak P, Leav I, Pursell B, Bae D, Yang X, Taglienti CA, Gouvin LM, Sharma VM, Mercurio AM. ERbeta impedes prostate cancer EMT by destabilizing HIF-1alpha and inhibiting VEGF-mediated snail nuclear localization: implications for Gleason grading. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:319–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuyama H, Hiramatsu Y. Involvement of suppressor for Gal 1 in the ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated degradation of estrogen receptors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:12020–12026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough H, Patterson C. CHIP: a link between the chaperone and proteasome systems. Cell stress & chaperones. 2003;8:303–308. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0303:calbtc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers MJ, Sun J, Carlson KE, Marriner GA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor-beta potency-selective ligands: structure-activity relationship studies of diarylpropionitriles and their acetylene and polar analogues. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2001;44:4230–4251. doi: 10.1021/jm010254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, Bos PD, Shu W, Giri DD, Viale A, Olshen AB, Gerald WL, Massague J. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JT, McKee DD, Slentz-Kesler K, Moore LB, Jones SA, Horne EL, Su JL, Kliewer SA, Lehmann JM, Willson TM. Cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor beta isoforms. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1998;247:75–78. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosselman S, Polman J, Dijkema R. ER beta: identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS letters. 1996;392:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolay R, Wiederkehr T, Rist W, Kramer G, Mayer MP, Bukau B. Dimerization of the human E3 ligase CHIP via a coiled-coil domain is essential for its activity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:2673–2678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noetzel E, Rose M, Bornemann J, Gajewski M, Knuchel R, Dahl E. Nuclear transport receptor karyopherin-alpha2 promotes malignant breast cancer phenotypes in vitro. Oncogene. 2012;31:2101–2114. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard N, Caron V, Bilodeau S, Sanchez M, Mascle X, Aubry M, Tremblay A. Identification of estrogen receptor beta as a SUMO-1 target reveals a novel phosphorylated sumoylation motif and regulation by glycogen synthase kinase 3beta. Molecular and cellular biology. 2012;32:2709–2721. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06624-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard N, Charbonneau C, Sanchez M, Licznar A, Busson M, Lazennec G, Tremblay A. Phosphorylation of activation function-1 regulates proteasome-dependent nuclear mobility and E6-associated protein ubiquitin ligase recruitment to the estrogen receptor beta. Molecular endocrinology. 2008;22:317–330. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell E, Shanle E, Brinkman A, Li J, Keles S, Wisinski KB, Huang W, Xu W. Identification of estrogen receptor dimer selective ligands reveals growth-inhibitory effects on cells that co-express ERalpha and ERbeta. PloS one. 2012;7:e30993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell E, Wang Y, Shapiro DJ, Xu W. Differential requirements of Hsp90 and DNA for the formation of estrogen receptor homodimers and heterodimers. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:16125–16134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell E, Xu W. Intermolecular interactions identify ligand-selective activity of estrogen receptor alpha/beta dimers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:19012–19017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807274105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastelli G, Tian ZQ, Wang Z, Myles D, Liu Y. Structure-based design of 7-carbamate analogs of geldanamycin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:5016–5021. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rody A, Holtrich U, Solbach C, Kourtis K, von Minckwitz G, Engels K, Kissler S, Gatje R, Karn T, Kaufmann M. Methylation of estrogen receptor beta promoter correlates with loss of ER-beta expression in mammary carcinoma and is an early indication marker in premalignant lesions. Endocrine-related cancer. 2005;12:903–916. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser MF, Washburn E, Muchowski PJ, Patterson C, Cyr DM. Chaperone functions of the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:22267–22277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saji S, Hirose M, Toi M. Clinical significance of estrogen receptor beta in breast cancer. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2005;56(Suppl 1):21–26. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta S, Sharma VM, Khan A, Mercurio AM. Regulation of IMP3 by EGFR signaling and repression by ERbeta: implications for triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:4689–4697. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M, Picard N, Sauve K, Tremblay A. Coordinate regulation of estrogen receptor beta degradation by Mdm2 and CREB-binding protein in response to growth signals. Oncogene. 2013;32:117–126. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte TW, Akinaga S, Soga S, Sullivan W, Stensgard B, Toft D, Neckers LM. Antibiotic radicicol binds to the N-terminal domain of Hsp90 and shares important biologic activities with geldanamycin. Cell stress & chaperones. 1998;3:100–108. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0100:arbttn>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanle EK, Hawse JR, Xu W. Generation of stable reporter breast cancer cell lines for the identification of ER subtype selective ligands. Biochemical pharmacology. 2011;82:1940–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanle EK, Zhao Z, Hawse J, Wisinski K, Keles S, Yuan M, Xu W. Research resource: global identification of estrogen receptor beta target genes in triple negative breast cancer cells. Molecular endocrinology. 2013;27:1762–1775. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau AK, Barstad D, Radek JT, Meyers MJ, Nettles KW, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA, Agard DA, Greene GL. Structural characterization of a subtype-selective ligand reveals a novel mode of estrogen receptor antagonism. Nature structural biology. 2002;9:359–364. doi: 10.1038/nsb787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotoca AM, van den Berg H, Vervoort J, van der Saag P, Strom A, Gustafsson JA, Rietjens I, Murk AJ. Influence of cellular ERalpha/ERbeta ratio on the ERalpha-agonist induced proliferation of human T47D breast cancer cells. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2008;105:303–311. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer SR, Coletta CJ, Tedesco R, Nishiguchi G, Carlson K, Sun J, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Pyrazole ligands: structure-affinity/activity relationships and estrogen receptor-alpha-selective agonists. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2000;43:4934–4947. doi: 10.1021/jm000170m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Li HL, Shi ML, Liu QH, Bai J, Zheng JN. Diverse roles of C-terminal Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) in tumorigenesis. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2014;140:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1571-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Meyers MJ, Fink BE, Rajendran R, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Novel ligands that function as selective estrogens or antiestrogens for estrogen receptor-alpha or estrogen receptor-beta. Endocrinology. 1999;140:800–804. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi Y, Kawabe Y, Chiba T, Murata S, Ichikawa K, Murayama A, Tanaka K, Baba T, Kato S, Yanagisawa J. Ligand-dependent switching of ubiquitin-proteasome pathways for estrogen receptor. The EMBO journal. 2004;23:4813–4823. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi Y, Sonoo R, Sekiya Y, Sunahara N, Kawano M, Wayama M, Hirota R, Kawabe Y, Murayama A, Kato S, et al. Turning off estrogen receptor beta-mediated transcription requires estrogen-dependent receptor proteolysis. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:7966–7976. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00713-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Gustafsson JA. The different roles of ER subtypes in cancer biology and therapy. Nature reviews Cancer. 2011;11:597–608. doi: 10.1038/nrc3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Rajapaksa G, Nikolos F, Hao R, Katchy A, McCollum CW, Bondesson M, Quinlan P, Thompson A, Krishnamurthy S, et al. ERbeta1 represses basal breast cancer epithelial to mesenchymal transition by destabilizing EGFR. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R148. doi: 10.1186/bcr3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay A, Tremblay GB, Labrie F, Giguere V. Ligand-independent recruitment of SRC-1 to estrogen receptor beta through phosphorylation of activation function AF-1. Molecular cell. 1999;3:513–519. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay GB, Tremblay A, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Labrie F, Giguere V. Cloning, chromosomal localization, and functional analysis of the murine estrogen receptor beta. Molecular endocrinology. 1997;11:353–365. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.3.9902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhao Z, Meyer MB, Saha S, Yu M, Guo A, Wisinski KB, Huang W, Cai W, Pike JW, et al. CARM1 methylates chromatin remodeling factor BAF155 to enhance tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer cell. 2014;25:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Hawse JR, Subramaniam M, Goetz MP, Ingle JN, Spelsberg TC. The tamoxifen metabolite, endoxifen, is a potent antiestrogen that targets estrogen receptor alpha for degradation in breast cancer cells. Cancer research. 2009;69:1722–1727. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XL, Subramaniam M, Grygo SB, Sun ZF, Negron V, Lingle WL, Goetz MP, Ingle JN, Spelsberg TC, Hawse JR. Estrogen receptor-beta sensitizes breast cancer cells to the anti-estrogenic actions of endoxifen. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13 doi: 10.1186/bcr2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Marcu M, Yuan X, Mimnaugh E, Patterson C, Neckers L. Chaperone-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP mediates a degradative pathway for c-ErbB2/Neu. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:12847–12852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202365899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Windheim M, Roe SM, Peggie M, Cohen P, Prodromou C, Pearl LH. Chaperoned ubiquitylation--crystal structures of the CHIP U box E3 ubiquitin ligase and a CHIP-Ubc13-Uev1a complex. Molecular cell. 2005;20:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QG, Han D, Wang RM, Dong Y, Yang F, Vadlamudi RK, Brann DW. C terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP)-mediated degradation of hippocampal estrogen receptor-alpha and the critical period hypothesis of estrogen neuroprotection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:E617–624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104391108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor beta: an overview and update. Nuclear receptor signaling. 2008;6:e003. doi: 10.1621/nrs.06003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Lam EW, Sunters A, Enmark E, De Bella MT, Coombes RC, Gustafsson JA, Dahlman-Wright K. Expression of estrogen receptor beta isoforms in normal breast epithelial cells and breast cancer: regulation by methylation. Oncogene. 2003;22:7600–7606. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Wang L, Wen Z, Ayaz-Guner S, Wang Y, Ahlquist P, Xu W. Systematic Analyses of the Cytotoxic Effects of Compound 11a, a Putative Synthetic Agonist of Photoreceptor-Specific Nuclear Receptor (PNR) Cancer Cell Lines. PloS one. 2013;8:e75198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Wang L, Xu W. IL-13Ralpha2 mediates PNR-induced migration and metastasis in ERalpha-negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2014;34(12):1596–607. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.