Abstract

Objectives

Evaluation of the Heartmate Risk Score and of its potential benefits in clinical practice.

Background

The Heartmate Risk Score (HMRS) has been shown to correlate with mortality in the cohort of patients enrolled in the Heartmate II trials but its validity in unselected, “real world” populations remains unclear.

Methods

We identified a cohort of 269 consecutive patients who received a Heartmate II left ventricular assist device at our institution between June 2005 and June 2013. 90-day and two year mortality rates as well as frequency of several morbid events were compared by retrospectively assigned HMRS category groups. The analysis was repeated within the subgroup of INTERMACS class 1 patients.

Results

Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) analysis showed that the HMRS correlated with 90-day mortality with an AUC of 0.70. Stratification in low, mid and high HMRS groups identified patients with increasing hazard of 90-day mortality, increasing long term mortality, increasing rate of GI bleeding events and increasing median number of days spent in the hospital in the first year post implant. Within INTERMACS class 1 patients, those in the highest HMRS group were found to have a relative risk of 90-day mortality 5.7 times higher than those in the lowest HMRS group (39.1% vs 6.9%, p=0.029).

Conclusions

HMRS is a valid clinical tool to stratify risk of morbidity and mortality after implant of Heartmate II devices in unselected patients and can be used to predict short term mortality risk in INTERMACS class 1 patients.

Keywords: heart failure, survival, transplantation, LVAD

Introduction

Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) have become the standard of care for patients with end stage heart failure both as a bridge to transplant (BTT) (1) and destination therapy (DT) (2). Over the past decade rates of LVAD implants in North America have grown exponentially, with the announcement of the 10,000th LVAD implant in the INTERMACS registry in June 2013(3). However, LVAD support remains associated with high morbidity and mortality and carries high costs(4). It is therefore critical to effectively risk stratify patients to identify patients with the greatest potential to benefit and to avoid futile implants. In addition, accurate risk stratification allows clinicians to correctly inform patients and their families as they consider this invasive therapeutic option.

Several clinical prediction rules have been developed to assess the likelihood of short term mortality after LVAD implantation (5, 6). Among these, the Heartmate Risk Score (HMRS) is a novel, simple, quantitative tool to predict mortality risk at 90-day in recipients of Heartmate II LVADs (HM II), independent of the implant strategy (DT vs BTT) (7). The HMRS was derived in a large cohort of patients enrolled in the HMII trials and was defined as a function of age, INR, albumin, creatinine and implant center volume. More than 1100 patients were evenly split in a derivation cohort and a validation cohort. The association between the HMRS and 90-day mortality was evaluated with the Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) analysis. Overall, stratification into low, mid and high HMRS categories was shown to identify patient populations with correspondingly low, intermediate and high 90-day mortality rates. In the derivation cohort, the HMRS was shown to have an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.77, while the AUC in the validation cohort was 0.64. Notably, the cohort of patients enrolled in the HMII trials is not well representative of today’s LVAD recipients (8). Furthermore, the HMRS was not compared with INTERMACS classification, arguably the most widely utilized tool to risk stratify LVAD recipients (6). Recently, the ability of the HMRS to correlate with mortality in “real world” patients was questioned (9). We sought out to retrospectively investigate the clinical utility of the HMRS in an unselected, consecutive cohort of Heartmate II recipients from our institution. Additionally, we intended to evaluate the ability of the HMRS to risk stratify INTERMACS 1 patients, a sub-group in which mortality is exceedingly high, and utility of durable LVADs is controversial.

Methods

Patient cohort

We retrospectively identified a cohort of 339 consecutive patients who underwent implantation of a continuous flow LVAD at Barnes-Jewish Hospital (BJH) between June 2005 and June 2013 (Supplementary figure 1). Within this cohort we identified 305 consecutive patients who received a Heartmate II® device (Thoratec Corp., Pleasanton, CA). Thirty-six HMII recipients were excluded; twenty-two had undergone LVAD exchange and fourteen had insufficient data to calculate the pre-operative HMRS. The most common reason for exclusion in this latter group was lack of albumin level pre-implant.

Patient characteristics and clinical outcomes were obtained through review of the medical records. All data were collected and managed using REDCap, an electronic data capture tool hosted by our institution (10). The HMRS was calculated reviewing chart data up to 1 week prior to implant day and using the available data closest to implant day. INTERMACS classification at the time of implant was dictated by the implanting surgeon in the operative note or assigned by the advanced heart failure team. HMRS was categorized into low (<1.58), mid (1.58-2.48) and high (>2.48) as previously described(7). Actuarial survival while on mechanical circulatory support was calculated from the date of implant to death and patients were censored as alive at the time of cardiac transplantation. The study was reviewed and approved by Washington University in St Louis Institutional Review Board.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of baseline characteristics between patients alive and dead at 90-day and between BJH cohort and HMRS derivation sample were conducted with Student’s two sample t-test and Fisher’s exact test for continuous and categorical data, respectively. Non-normal and ordinal data were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test and were summarized by the median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile). A Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve to assess the ability of HMRS, as a continuous variable, to predict 90-day mortality was generated along with the area under the curve (AUC). Additionally, a logistic regression model was built to evaluate all pair-wise comparisons of 90-day mortality between HMRS category levels. Tukey’s method for multiple comparisons was used to adjust p-values. To account for different length of follow-up time among patients, the number of GI bleeding events, strokes, hemolysis events and days in hospital within first year were evaluated with a Poisson regression model having the log follow-up years as offset and scaled to account for over-dispersion. Pair-wise comparisons among HMRS categories were conducted through the model and Tukey’s method for multiple comparison tests was used to adjust p-values. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were developed by HMRS category to evaluate long-term (2 year) survival. The log-rank test was used to assess differences between curves.

The results from a logistic model including only HMRS were compared to a model including HMRS, history of CAD, and vasopressors to evaluate the ability to improve upon HMRS as a predictor of 90-day mortality. The impact of these additional variables to the HMRS was evaluated by comparing the change in the c-statistic and calculating the category-free Net Reclassification Improvement (category-free NRI).(11) Data analysis was performed with SAS (Cary, North Carolina) and GraphPad Prism 6 (Software MacKiev).

Results

Characteristics of the BJH cohort and HMRS derivation cohort

Basic characteristics of the BJH cohort are shown in Table 1. The cohort was composed predominantly of Caucasian males. The average age was 55.9 years. Thirty-three percent of the cohort was classified as INTERMACS class 1 at the time of implant. Compared with the HMRS derivation cohort, the baseline characteristics were similar (Table 2) in terms of HMRS variables as well as in gender, race, and use of intravenous inotropes or intra-aortic balloon pump prior to LVAD. The BJH cohort was enriched in BTT patients when compared with the HMRS derivation cohort (67% vs 42%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the Barnes-Jewish Hospital cohort of LVAD recipients

| Variable, No. (%) | Overall (N=269) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.9 ± 12.1 |

|

| |

| Caucasian | 200 (74%) |

|

| |

| Male | 217 (81%) |

|

| |

| BMI | 28.9 ± 6.2 |

|

| |

| Strategy | |

| • Bridge to Transplant | 181 (67%) |

| • Destination Therapy | 86 (32%) |

|

| |

| INTERMACS Profile | |

| • 1 | 89 (33%) |

| • 2 | 146 (54%) |

| • 3 | 17 (6%) |

| • 4 or more | 17 (6%) |

|

| |

| Ischemic Cardiomyopathy | 116 (43%) |

|

| |

| STEMI in last 30 days | 11 (4%) |

|

| |

| Vasopressors prior to LVAD | 29 (13%) |

|

| |

| Inpatient inotropes prior to LVAD | 184 (85%) |

|

| |

| Balloon pump prior to LVAD | 58 (27%) |

Values are n (%). Age is expressed as mean +/- standard deviation. BMI = Body Mass Index, LVAD = Left Ventricular Assist Device

Table 2.

Comparison of BJH cohort and HMRS derivation cohort

| Variable | HMRS derivation cohort (N=583) | BJH cohort (N=269) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.3 ± 13.3 | 55.9 ± 12.1 | 0.85 |

| Male | 450 (77%) | 217 (81 %) | 0.28 |

| Caucasian | 433 (74%) | 200 (74%) | 1.00 |

| BTT | 245 (42%) | 181 (67%) | <.001 |

| Intravenous inotropes prior to VAD | 495 (85%) | 184 (85%) | 1.00 |

| IABP prior to LVAD | 177 (30%) | 58 (27%) | 0.34 |

| Creatinine | 1.47 ± 0.55 | 1.57 ± 0.80 | 0.88 |

| Albumin | 3.44 ± 0.58 | 3.54 ± 0.54 | 0.86 |

| INR | 1.31± 0.33 | 1.58± 0.51 | 0.50 |

Values are n (%). Age is expressed as mean +/- standard deviation. BTT = Bridge to transplant, IABP = Intra-aortic balloon pump. LVAD = Left Ventricular Assist Device.

HMRS and 90-day mortality

ROC analysis for HMRS as predictor of 90-day mortality yielded an AUC of 0.70, 95% CI = (0.60, 0.79). Patients in the highest HMRS group had a relative risk of 90-day mortality 3.9 times greater than those in the lowest HMRS group (32.7% vs 8.3%, p=0.001) and 2.6 times greater than those in the mid HMRS group (32.7% vs 12.5%, p = 0.01) (Figure 1). Our center contributed 37 patients to the HMII trials. In order to avoid any potential bias in our results we repeated the analysis excluding all patients implanted during the time of recruitment in the HMII landmark studies and we obtained very similar results (AUC 0.68).

Figure 1. Predicting 90-day Mortality on the Basis of HMRS.

Ninety day mortality rate in the BJH LVAD cohort stratified by Heartmate Risk Score (HMRS) group. The number of patients in each group (n) is indicated below each bar.

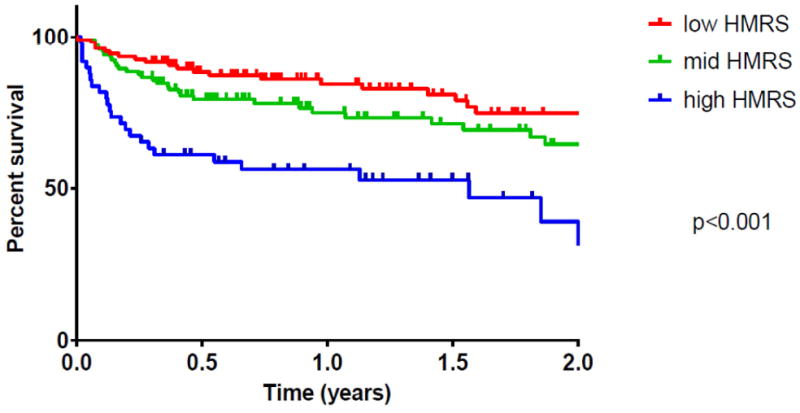

HMRS and long term outcomes after LVAD implant

Kaplan-Meyer survival analysis censoring patients as alive at the time of heart transplant, showed a statistically significant difference in long term survival between the high, mid, and low HMRS groups (log rank p< 0.001) (Figure 2). In order to assess the ability of the HMRS to predict life span while on mechanical support, we assessed long-term survival in patients who received LVAD as destination therapy (DT). We found that the 2-year mortality of DT patients in the high HMRS category was 84.6% as compared to 36.4% in the low HMRS group (RR = 2.32, p=0.029) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Long Term Mortality on the Basis of HMRS.

Kaplan-Meyer Survival of HMII recipients in the BJH cohort stratified by HMRS group. Log-Rank test p = 0.001.

Figure 3. Long Term Mortality in Destination Therapy Patients on the Basis of HMRS.

Two year mortality rate in patients who received an LVAD as Destination Therapy (DT) stratified by HMRS group.

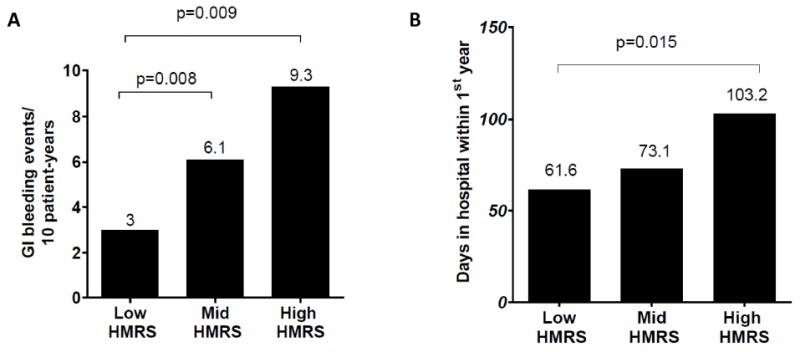

HMRS and morbidity after LVAD implant

The association between pre-operative HMRS and stroke rate, hemolysis/pump thrombosis rate, implant hospitalization length of stay, GI bleeding events rate and cumulative days hospitalized in the first year post implant were evaluated. While HMRS did not correlate with stroke rate, hemolysis/pump thrombosis rate, implant hospitalization length of stay (data not shown), patients in the high HMRS category had a significantly higher rate of GI bleeding events than patients in the low HMRS (9.3/10 patient years vs 3/10 patient years, p=0.009) (Figure 4A). Additionally, when compared to patients with low HMRS, subjects in the high HMRS category spent a greater number of days in the hospital in the first year post LVAD (103.2 vs 61.6 days, p= 0.015) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. GI Bleeding events and days spent in the hospital on the Basis of HMRS.

(A) Median rate of GI bleeding events per 10 patient-years stratified by HMRS group. (B) Median number of days spent in the hospital in the first 365 days post LVAD implant stratified by HMRS group.

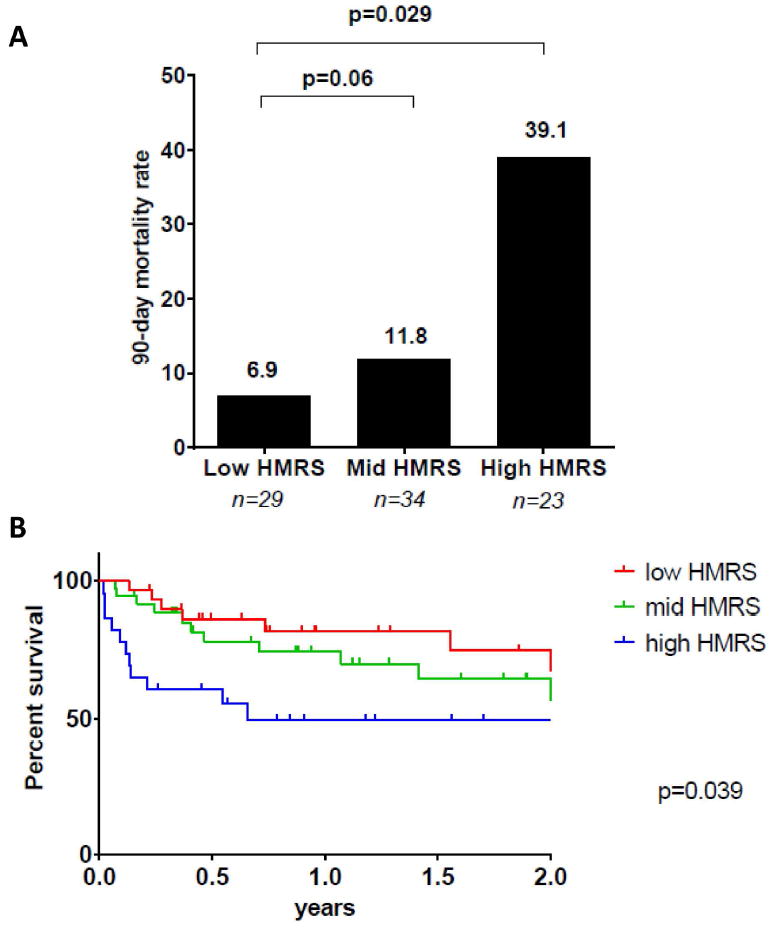

HMRS in INTERMACS class I patients

One-third of the BJH cohort was classified as INTERMACS class I prior to LVAD implant (n=89, 33%, table 1 and supplementary table 1). As shown in Figure 5, HMRS categorization effectively stratified mortality risk among INTERMACS class 1 patients, both in terms of 90-day mortality (Fig 5A) and long-term mortality (Fig 5B). The AUC for the HMRS ability to predict 90 days mortality among INTERMACS class 1 patients was 0.75 and INTERMACS class 1 patients in the high HMRS group had a relative risk of mortality at 90-day that was 5.7 times higher than those in the lowest HMRS group (39.1% vs 6.9%, p=0.029). Kaplan-Meyer survival analysis censoring patients as alive at the time of heart transplant showed a significant difference in long term survival across the three HMRS levels (log-rank p=0.039).

Figure 5. Short and Long Term Mortality in INTERMACS Class 1 Patients on the Basis of HMRS.

(A) Ninety day mortality rate in INTERMACS class 1 LVAD recipients stratified by HMRS group. The number of patients in each group (n) is indicated below each bar. (B) Kaplan-Meyer Survival Stratified by HMRS group among INTERMACS class 1 LVAD recipients. Log-Rank test p = 0.039. 3 patients were excluded from this analysis because they were censored prior to 90 days.

HMRS and other common clinical variables

We investigated the association with 90 day mortality of a number of variables not included in the HMRS. In univariate analysis, two variables not included in the HMRS were significantly associated with 90-day mortality (Table 3): history of coronary artery disease (OR 1.38, p= 0.05) and use of vasopressors prior to implant (OR 3.2, p= 0.002) (Table 3). However, in multivariate analysis with the HMRS only pre-operative use of vasopressors maintained a statistically significant association with mortality. Addition of the variable “preoperative use of vasopressors” to the HMRS provided only marginal improvement in the ability of the score to predict 90-day mortality as shown by a modest, non-statistically significant change in the category free Net Reclassification Improvement (Supplementary Table 2). We tested all the variables listed in Table 3 for association with 90 days mortality focusing only on the subgroup of INTERMACS class 1 patients and found similar results (Supplementary table 3).

Table 3.

Univariable correlates of 90-day mortality in BJH cohort

| Variable | Overall (N=303) | Alive at 90 days (N=249) | Dead at 90 days (N=45) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian, No. (%) | 227 (75%) | 189 (76%) | 32 (71%) | 0.57 |

| Male, No. (%) | 239 (79%) | 198 (80%) | 33 (73%) | 0.43 |

| Age (years) | 56.19 ± 11.91 | 55.94 ± 11.99 | 58.98 ± 9.94 | 0.11 |

| BMI | 28.93 ± 6.19 | 28.79 ± 6.12 | 29.81 ± 6.27 | 0.31 |

| Strategy, No. (%) | 0.020 | |||

| • Bridge to Transplant | 204 (67%) | 176 (71%) | 23 (51%) | |

| • Destination Therapy | 95 (31%) | 71 (29%) | 21 (47%) | |

| History of Atrial Fibrillation, No. (%) | 130 (43%) | 107 (43%) | 21 (47%) | 0.74 |

| Smoking within 3 months, No. (%) | 29 (10%) | 22 (9%) | 6 (14%) | 0.41 |

| History of CAD, No. (%) | 155 (51%) | 121 (49%) | 30 (67%) | 0.034 |

| STEMI in past 30 days, No. (%) | 12 (4%) | 11 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.23 |

| History of DM, No. (%) | 126 (42%) | 99 (40%) | 23 (51%) | 0.19 |

| COPD, No. (%) | 40 (13%) | 34 (14%) | 6 (13%) | 1.00 |

| History of Ethanol Abuse, No. (%) | 2 (13%) | 2 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| History of hypertension, No. (%) | 145 (48%) | 119 (48%) | 22 (49%) | 1.00 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy, No. (%) | 136 (45%) | 109 (44%) | 22 (49%) | 0.63 |

| CABG at time of implant No. (%) | 14 (6%) | 9 (5%) | 4 (11%) | 0.12 |

| Redo sternotomy, No. (%) | 67 (28%) | 56 (28%) | 10 (29%) | 1.00 |

| Vasopressors prior to VAD, No. (%) | 35 (14%) | 22 (11%) | 11 (29%) | 0.008 |

| Inpatient inotropes prior to VAD, No.(%) | 214 (86%) | 171 (84%) | 34 (89%) | 0.62 |

| IABP prior to VAD, No. (%) | 64 (25%) | 50 (25%) | 12 (31%) | 0.43 |

Comparisons of patients alive and dead at 90 days were conducted with Student’s two sample t-test and Fisher’s exact test for continuous and categorical data, respectively. The p value for the difference between the 2 groups is indicated. VAD = Ventricular assist device; BMI = Body Mass Index; CAD = coronary artery disease; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pump, CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting

Discussion

The HMRS correlates with short and long term survival post LVAD

The HMRS was derived from a large, multicenter, trial population and proposed as a novel and accurate risk predictive model for short-term survival after LVAD implant (7) but to date its applicability to “real world” patients remains controversial (9). The current study demonstrates that the HMRS correlates with 90-day mortality (AUC 0.70) in an unselected cohort of HMII LVADs from a single large volume center and can identify patients with low (≈ 8%), medium (≈ 12%), and high (≈ 32%) risk of 90 day mortality for implant of a HMII device. This correlation is very similar to that described in the HMRS derivation paper that found an AUC of 0.71 and in the validation cohort found mortality rates of approximately 8%, 12% and 26% in low, mid and high HMRS groups (7). Importantly, while our center was involved in the HMII trials and contributed some patients to the cohort used to derive the HMRS, the overlap between the two cohorts is minimal and exclusion of all the patients potentially included in the HMRS derivation cohort did not significantly change our results.

In addition to confirming what was previously described, we observed that the HMRS significantly discriminates patient groups with respect to survival at two years. Further, by stratifying the DT subgroup by HMRS, DT patients in the high HMRS were observed to have a 2 year mortality rate almost 2.5 times higher than patients in the low HMRS category. These observations suggest that the correlation between HMRS and long term outcomes reflects a correlation between pre-operative HMRS category and ability to tolerate long term mechanical circulatory support independent from receiving a heart transplant.

HMRS risk stratifies INERMACS class 1 patients

Patients with INTERMACS 1 classification are defined as “crashing and burning” subjects, with cardiogenic shock refractory to inotropes. In-hospital mortality in this sub-group remains exceedingly high and current recommendations are unclear about the utility of durable LVADs in this subgroup (6, 12). This observation has led some groups to utilize alternative strategies to durable LVADs in INTERMACS 1 patients and the number of implants in this population recorded in the INTERMACS registry has correspondingly decreased from 41% in 2006 to 14%-16% in 2011/2012 (13, 14). However, INTERMACS classification provides a snapshot of hemodynamic status and in the presence of severe hemodynamic compromise does not invariably discriminate between patients with preserved organ function and patients with longstanding multi organ dysfunction. Here we show that within this most acutely ill INTERMACS stratum, the HMRS provides the ability to discriminate between patient groups with a risk of 90-day mortality raging from as low as 6.9 percent to as high as 39 percent. This observation suggests that quantitative risk models such as the HMRS may help clinicians to better identify those critically ill patients who are more likely to benefit from durable mechanical circulatory support, as well as identify those patients who are unlikely to benefit from mechanical circulatory support.

HMRS correlates with morbidity post LVAD

The current study also describes a previously unrecognized correlation between HMRS and morbid events post LVAD implant. In fact, we found a statistically significant difference in post-LVAD GI bleeding events rates and number of days spent in the hospital in the first year post implant between HMRS groups. The mid HMRS patients had a 2 fold increase and high HMRS patients had 3 fold increase in GI bleeding events per 10 patient years of follow-up compared with the low HMRS patients. Moreover, the high HMRS patients spent 67% more days in the hospital in the first year post implant when compared to the low HMRS group. This stands to reason as the HMRS incorporates patient age, an identified risk factor for GI bleeding (15), and INR, an indicator of preoperative coagulopathy and liver dysfunction. This observed large difference in rates of GI bleeding, which generally results in prolonged hospitalization, may alone explain the increase inhospital days within the first year that we found for high HMRS versus low HMRS subjects as we identified no difference in length of stay at the time of implant across HMRS groups (data not shown). The ability of the HMRS to predict these and other lifestyle-limiting post-LVAD complications merits further study as this information may provide important background for both clinician and patient when considering LVAD implant.

The HMRS captures most of the predictive power of commonly measured clinical variables

Although our data validates the predictive accuracy of the HMRS in a real world cohort of Heartmate II recipients, it bears emphasis that both in our cohort as well as in the HMII trials cohort, the HMRS has a modest discriminative ability for predicting 90-day mortality with an AUC of 0.70. Since the original HMRS score was limited to data available in the clinical trials, we sought additional variables which may improve its discriminative ability. In contrast to what was observed in the HMRS derivation cohort, we found that use of vasopressors prior to LVAD implant correlated with 90-day mortality in multivariate analysis with the HMRS. However, the addition of this variable did not significantly improve the ability to predict 90-day mortality. Overall our findings suggests that the HMRS captures most of the predictive power of commonly measured clinical variables and that further work on significantly larger cohorts or the analysis of novel variables would be needed in order to generate an improved risk model that could improve risk stratification of LVAD recipients.

Discrepancy with other published work

Our data is in line with what was observed in the trial cohort of approximately 1100 patients used to derive and validate the HMRS. Interestingly, another large volume center applied the HMRS retrospectively to their CF-LVAD cohort and did not find a correlation between HMRS and 90-day mortality (9). The reason for the difference between findings in “real world” patients at this center and our institution remains unclear. In comparison, our cohort was larger (261 implants vs 201), had similar annual implant volume, fewer patients with low HMRS (41% vs 50%), and a lower prevalence of BTT (67% vs 76%), though 90-day mortality was essentially the same (14.5% vs 15.1%). None of these differences appear sufficient enough to clearly account for the discrepant results. Additionally, our analysis excluded VAD exchange implants and included a relatively high number of INTERMACs class 1 patients. This data is not available in the published analysis, but is a potential difference between the two. Ultimately, both retrospective analyses have limited power and thus the observed discrepancy could represent random variability. Further analysis in other cohorts and larger databases are needed to further understand the value of the HMRS in real-world patients and to better identify the possible basis of the observed discrepancies.

Study limitations

It should be emphasized that some of our findings may not be applicable in low volume centers that implant LVADs, insofar the HMRS gives a large “penalty” to patients who received their LVAD in an institution that implants less than 15 LVADs per year. In our population this penalty was not applied and therefore our findings might not apply to the HMRS calculated for patients implanted in lower volume centers. Further, the ability of the HMRS to predict GI bleeding as well as days spent in the hospital within the first year post LVAD implant and its ability to risk-stratify INTERMACS class 1 patients have not been described previously and therefore will require evaluation in additional patient populations. Finally, we have performed a retrospective analysis and have therefore shown correlation between HMRS and clinically relevant events. While this type of analysis suggests predictive value, a prospective study would be required to more definitively assess the ability of the HMRS to predict clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

In summary, we validated the HMRS in a large, unselected cohort of HMII recipients from a single, high-volume center. We demonstrated that the HMRS correlates with short and long terms survival as well as rates of future GI bleeding and days spent in the hospital in the first year post implant. We also showed that the HMRS can effectively risk-stratify INTERMACS class 1 patients, identifying individuals with high and low risk of 90-day mortality. These findings confirm the performance of the HMRS as a risk stratification tool for pre-operative assessment of LVAD candidates and suggest that the HMRS may be useful in patient selection, especially among the most critically ill patients. Further work in other cohorts or in larger multicenter databases is needed to confirm our findings and to clarify discrepancies in the performance of the HMRS observed across different centers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This study was supported in part by research funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH grant U10 HL110309, Heart Failure Network). No relationships with industry.

Disclosures: Dr. Greg Ewald received consulting fees from Thoratec Corporation

Abbreviations

- LVAD

left ventricular assist device

- INTERMACS

Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support

- HMII

Heartmate II

- HVAD

Heartware Ventricular Assist Device

- GI bleeding

Gastro intestinal bleeding

- HMRS

Heartmate Risk Score

- ROC

Receiver Operating Curve

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, et al. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:885–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1435–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, et al. Sixth INTERMACS annual report: a 10,000-patient database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:555–64. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long EF, Swain GW, Mangi AA. Comparative survival and cost-effectiveness of advanced therapies for end-stage heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:470–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy WC. Potential clinical applications of the HeartMate II risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:322–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle AJ, Ascheim DD, Russo MJ, et al. Clinical outcomes for continuous-flow left ventricular assist device patients stratified by pre-operative INTERMACS classification. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:402–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowger J, Sundareswaran K, Rogers JG, et al. Predicting survival in patients receiving continuous flow left ventricular assist devices: the HeartMate II risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SJ, Milano CA, Tatooles AJ, et al. Outcomes in advanced heart failure patients with left ventricular assist devices for destination therapy. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:241–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas SS, Nahumi N, Han J, et al. Pre-operative mortality risk assessment in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: Application of the HeartMate II risk score. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:675–81. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uno H, Tian L, Cai T, Kohane IS, Wei LJ. A unified inference procedure for a class of measures to assess improvement in risk prediction systems with survival data. Stat Med. 2013;32:2430–42. doi: 10.1002/sim.5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevenson LW, Pagani FD, Young JB, et al. INTERMACS profiles of advanced heart failure: the current picture. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:535–41. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. Fifth INTERMACS annual report: risk factor analysis from more than 6,000 mechanical circulatory support patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:141–56. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. The Fourth INTERMACS Annual Report: 4,000 implants and counting. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uriel N, Pak SW, Jorde UP, et al. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome after continuous-flow mechanical device support contributes to a high prevalence of bleeding during long-term support and at the time of transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.