Abstract

Background

Successful human reproduction depends on the fusion of a mature oocyte with a sperm cell to form a fertilized egg. The genetic events that lead to human oocyte maturation arrest are unknown.

Methods

We recruited a rare four-generation family with female infertility as a consequence of oocyte meiosis I arrest. We applied whole-exome and direct Sanger sequencing to an additional 23 patients following identification of mutations in a candidate gene, TUBB8. Expression of TUBB8 and all other β-tubulin isotypes was measured in human oocytes, early embryos, sperm cells and several somatic tissues by qRT-PCR. The effect of the TUBB8 mutations was assessed on α/β tubulin heterodimer assembly in vitro, on microtubule architecture in HeLa cells, on microtubule dynamics in yeast cells, and on spindle assembly in mouse and human oocytes via microinjection of the corresponding cRNAs.

Results

We identified seven mutations in the primate-specific gene TUBB8 that are responsible for human oocyte meiosis I arrest in seven families. TUBB8 expression is unique to oocytes and the early embryo, where this gene accounts for almost all of the expressed β-tubulin. The mutations affect the chaperone-dependent folding and assembly of the α/β-tubulin heterodimer, induce microtubule chaos upon expression in cultured cells, alter microtubule dynamics in vivo, and cause catastrophic spindle assembly defects and maturation arrest upon expression in mouse and human oocytes.

Conclusions

TUBB8 mutations function via dominant negative effects that massively disrupt proper microtubule behavior. TUBB8 is a key gene involved in human oocyte meiotic spindle assembly and maturation.

INTRODUCTION

Successful human reproduction starts when a metaphase II oocyte fuses with a sperm cell to form a fertilized egg. In human oocytes, the meiotic cell cycle begins in the neonatal ovary and pauses at prophase I of meiosis until puberty, when a surge of luteinizing hormone stimulates the resumption of meiosis and ovulation. This leads to progression of the oocyte from metaphase I (MI) to metaphase II (MII) 1–3. Prophase I-arrested oocytes have an intact nucleus termed the germinal vesicle (GV), while oocytes that have resumed meiosis are characterized by GV breakdown. Following GV breakdown, MI is completed by extrusion of a polar body and asymmetric division; mature oocytes are again arrested at MII 4. In most mammals, this is the only stage at which oocytes can be successfully fertilized 1.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) now accounts for 1–3% of annual births 5. It is common for some patient oocytes to remain immature after ovarian stimulation and human chorionic gonadotropin administration 6, but only a few examples of complete oocyte maturation arrest have been reported 7–12, and no genes responsible for human oocyte maturation arrest have been identified. Here we describe a rare multi-generation family with multiple infertile female members as well as six unrelated families with similar oocyte maturation arrest phenotypes. The afflicted members all carry either a paternally originated autosomal dominant or de novo mutation in TUBB8, a β-tubulin-encoding gene of hitherto unknown function that is unique to primates. We show that in humans, TUBB8 is uniquely expressed in the developing oocyte, providing an essential component of the oocyte spindle. The disease-associated mutations affect the α/β-tubulin heterodimer folding and assembly pathway, alter microtubule dynamics in yeast, and disrupt microtubule organization upon expression in either cultured cells or mouse or human oocytes. These microtubule phenotypes entail a dominant negative effect leading to defective microtubule behavior and oocyte maturation arrest, and establish TUBB8 as an essential and functionally specialized β-tubulin that contributes to human oocyte meiotic spindle assembly and maturation.

METHODS

Human subjects

24 patients from families with oocyte maturation arrest were referred from the Reproductive Medicine Center at Ninth Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University, the Shanghai Ji Ai Genetics and IVF Institute of Reproductive Medicine Center and Shaanxi Maternal and Child-care Service Center. Studies of human subjects and mice were approved by the Fudan University Medicine Institutional Review Board. Additional information is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Study design

We used exome and targeted gene sequencing to identify mutations in the TUBB8 gene. Gene expression analysis of oocytes, structural implications, functional effects of mutations in vitro, in HeLa cells, in yeast and in mouse/human oocytes were used to elucidate the mechanism of mutations that cause oocyte meiotic arrest as well as to establish a causal relationship between mutations and phenotypes. Our methods are described in detail in the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix.

RESULTS

Human oocyte maturation arrest and TUBB8

We initially identified a rare four-generation family in which primary female infertility was transmitted via an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern (Figure 1). All the spouses had normal sperm counts, sperm morphology and motility. Attempted IVF with patient III-5 resulted in oocytes that were at the MI stage (Table 1); these failed to proceed to maturation even after extended culture in vitro. Patient III-4 yielded three oocytes at the MI stage and one with abnormal morphology; none of these had a visible spindle by polarization microscopy (Figure 2A,B), and the oocyte with abnormal morphology later failed to become fertilized. Six additional families (Families 2–7) were identified thereafter (Figure 1). Each patient in these families underwent 2–5 failed IVF attempts. Almost all oocytes harvested during these attempts were arrested at the MI stage, and none had a visible spindle (Table 1, Figure 2C–E). Examination of one MI oocyte from patients belonging to families 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 by immunostaining showed either an abnormal spindle or no detectable spindle (Figure 2F). Thus, all patients were devoid of mature MII oocytes.

Figure 1. Pedigree and mutations in TUBB8 in oocytes maturation arrest patients.

Pedigrees of seven families with inherited or de novo TUBB8 mutations. Family 1 is a large four-generation family that includes five affected women with long-term primary infertility. The V229A mutation in TUBB8 was inherited from the patients’ father. Family member IV-1 is a 7-year-old girl carrying the mutation who cannot be evaluated for fertility. The D417N, M363T, R2K and M300I mutations were identified in families 2, 5, 6 and 7, respectively. These four mutations were inherited from the respective fathers. The S176L and R262Q mutations identified in families 3 and 4 are de novo. Sanger sequencing chromatograms are shown defining the nature and location of the mutations in each family. Squares denote male family members and circles female family members. Black circles represent affected individuals. Slashes indicate deceased individuals. The arrow indicates the index patient. WT, wild type.

Table 1.

Clinical details and IVF/ICSI outcome in patients from families 1–7

| Case | Age (years) | Duration infertility (years) of | Previous IVF/ICSI cycles | Total No of oocyte retrieved | Stage of Oocyte (Number) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family-1 | III-4 (V229A) | 37 | 8 | 1 | 4 | MI(3)+abnormal morphology oocyte(1) |

| Family-1 | III-5 (V229A) | 32 | 10 | 2 | 21 | MI(21) |

| Family-2 | II-2 (D417N) | 37 | 9 | 5 | 37 | GV(7)+MI(30) |

| Family-3 | II-1 (S176L) | 34 | 10 | 4 | 43 | GV(3)+MI(40) |

| Family-4 | II-1 (R262Q) | 37 | 10 | 2 | 12 | MI(12) |

| Family-5 | II-1 (M363T) | 25 | 4 | 3 | 18 | GV(1)+MI(17) |

| Family-6 | II-1 (R2K) | 33 | 7 | 2 | 54 | GV(2)+MI(52) |

| Family-7 | II-1 (M300I) | 26 | 6 | 2 | 26 | MI (26) |

Figure 2. Phenotypes of oocytes from patients with maturation arrest.

(A–E) Normal (A) and patient (B–E) oocytes were separated from granulosa cells and examined by light and polarization microscopy. Note that a normal MII oocyte has a first polar body (black arrow in A) and that normal MI and MII oocytes have visible spindles (white arrows in A). All patient oocytes are at MI and none have a first polar body. Oocytes in patients from families 1 (B), 2 (C), and 6 (E) have no visible spindle (polarization microscopy data was not obtained for oocytes from the patient in family 3). (F) Oocytes from control, V229A, D417N, S176L, R262Q and R2K patients were fixed, permeabilized, immunolabeled and examined by confocal microscopy using antibodies against β-tubulin to visualize the spindle (shown in green) and counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (shown in blue) to visualize DNA. Note that the oocyte from the D417N patient has an abnormal (disorganized) spindle, while oocytes from all other patients have no visible spindle.

To identify the genetic defect responsible for oocyte maturation arrest, we performed whole-exome sequencing on samples from several patients in family 1 (see Methods). This resulted in the identification of a novel heterozygous missense c.T686C (p.V229A) mutation in the coding region of TUBB8, a gene that encodes a primate-specific β-tubulin isotype of unknown function. This gene co-segregated with female infertility in family 1, and was inherited from a male (Figure 1). We subsequently identified other TUBB8 mutations in six unrelated infertile patients with a similar oocyte maturation arrest phenotype. These mutations were found in two patients in family 2 (c.G1249A, p.D417N), a patient in family 5 (c.T1088C, p.M363T), a patient in family 6 (c.G5A, p.R2K) and a patient in family 7 (c.G900A, p.M300I). These four mutations were all inherited from the patients’ fathers. In addition, for patients in families 3 and 4, de novo mutations (c.G785A, p.R262Q; c.C527T, p.S176L, respectively) were detected (Figure 1). These results and an analysis of allele-specific expression in a single S176L oocyte (Figures S1A, S1B) reinforce the notion that the TUBB8 mutations are likely to be responsible for oocyte maturation arrest. The location and strict evolutionary conservation of the mutated residues is shown in Figure S2.

TUBB8 supplies almost all the β-tubulin in human oocytes

Microtubules are dynamic polymers assembled from α/β-tubulin heterodimers 13. A total of nine β-tubulin isotypes is expressed in mammals, mainly distinguished by variations in the acidic carboxy-terminal tail that influence specific cellular functions14. Mutations in TUBB1, TUBB2A, TUBB2B, TUBB3, TUBB4A and TUBB4B have been described; these cause a broad range of diseases for the most part involving microtubule-based defects in neuronal migration 15–17. TUBB8 is of entirely unknown function in microtubule biology, and is unusual in that it exists only in primates. We therefore surmised that TUBB8 might play an important role in determining microtubule behavior in primate oocytes, where the self-organization of microtubules and motor proteins direct meiotic spindle assembly and chromosome orientation 18, 19. Strikingly, we found that TUBB8 is the only β-tubulin isotype expressed at a high level at different stages of human oocyte development, while it is essentially absent in mature sperm and in somatic tissues such as brain and liver (Figure S3). Immunostaining of human oocytes at different developmental stages using either an ostensibly specific anti-TUBB8 antibody or an anti-FLAG antibody in the case of a human GV oocyte microinjected with TUBB8-FLAG complementary RNA (cRNA) confirmed that TUBB8 is indeed localized to the spindle (Figures S4A, S4B). TUBB8 is thus a clear candidate for contributing to spindle assembly and oocyte development.

Structural implications

We mapped the affected residues onto the atomic structure of tubulin (PDB: 3JAS) 20. S176 is located at a longitudinal interface between assembled dimers where it interacts with α-tubulin (Figure S5A), and lies in a key region (residue V177-S178-D179) in the β-T5 loop that changes upon GTP hydrolysis 20, 21. It is likely that the S176L mutation disrupts longitudinal interactions, thus inhibiting microtubule assembly. M363 may interact with V288 within the M-loop (Figure S5B). The M363T mutation could potentially weaken the interaction with V288 and thus cause microtubule instability 22. D417 and R262 interact with each other forming a salt bridge on the outside surface of the microtubule (Figure S5C); this would be broken by the D417N and R262Q mutations. D417 is known to be involved in kinesin binding 23 and its mutation would be likely to have a negative effect on the interaction of microtubules with kinesin and potentially other MAPs. M300, and V229 are buried within the β-tubulin subunit and their mutation could destabilize its folding (Figure S5B). Finally, R2 is located at the α–β interface within the heterodimer (Figure S5A), and this mutation could affect dimer assembly and stability.

α/β heterodimer assembly in vitro

The de novo generation of tubulin heterodimers requires the concerted action of a spectrum of chaperones: prefoldin (PFD), the ATP-dependent cytosolic chaperonin (CCT), and five tubulin-specific chaperones termed TBCA-TBCE that function in concert downstream of CCT as a GTP-dependent heterodimer assembly nanomachine 24. To investigate potential folding defects incurred as a result of mutation, we followed the assembly of 35S-labeled wild type and mutant-bearing TUBB8 polypeptides kinetically. None of the mutations had any influence on translational efficiency (Figure S6A). However, the various TUBB8 mutants displayed a spectrum of quantitative differences in the characteristic flow of label from the PFD/β and CCT/β-tubulin binary complexes to TBCA/β-tubulin and TBCD/β-tubulin compared to the wild type control (Figure S6B and Table S2). These data reveal a range of heterodimer assembly defects caused by the TUBB8 mutations, in some cases attributable to changes in the equilibria that govern the de novo assembly of heterodimers 24, in others pointing to misfolding, and in most cases leading to a diminished yield of assembled heterodimers.

Microtubule disruption in vivo

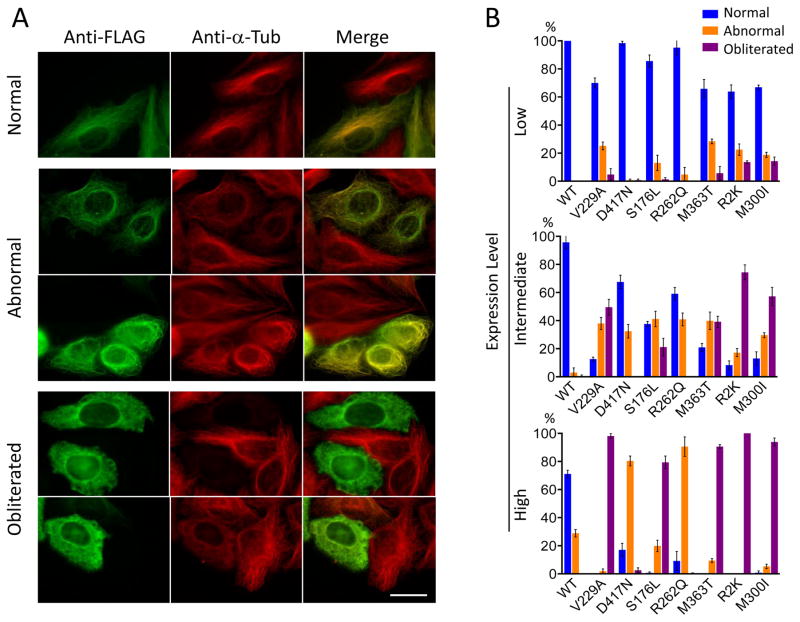

To explore the influence of the TUBB8 mutations on microtubule behavior in vivo, we transfected FLAG-tagged constructs into cultured (HeLa) cells. In the case of wild type TUBB8, except at high levels of transgene expression, we found co-assembly into a normal microtubule network (Figure 3A, top panels). In contrast, in the case of the TUBB8 mutants, at intermediate or high levels of expression, the TUBB8 protein frequently became incorporated into microtubules that had an abnormal appearance (Figure 3A, center panels), and in many cases caused complete loss of the microtubule network (“obliteration”) (Figure 3A, lower panels). The obliteration phenotype is most strongly associated with mutations predicted to interfere with either dimer stability, β-tubulin folding or polymerization (V229A, S176L, M363T, R2K, M300I), while those predicted to interfere with kinesin binding (R262Q and D417N) result in altered microtubule organization while retaining their capacity to co-assemble (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Microtubule phenotypes resulting from expression of wild type and mutant forms of TUBB8 in cultured cells.

(A) Expression of wild type and mutant forms of TUBB8 in cultured cells. Constructs engineered for the expression of C-terminally FLAG-tagged TUBB8 (wild type and mutant) were expressed by transfection into HeLa cells. After 42 h, the cells were fixed, permeabilized and labeled with antisera to the FLAG epitope (to detect expression of the transgene, shown in green) and α-tubulin (to detect the endogenous microtubule network, shown in red). Examples are shown of cells expressing the various transgenes in which there was incorporation into a normal interphase microtubule network, an abnormal microtubule network with either a conspicuously reduced filament density or with a wavy, tangled or disorganized appearance, or cells in which the microtubule network had been completely obliterated. Note that in the latter cases, the FLAG and α-tubulin labels appear as a diffuse mottled pattern throughout the cytoplasm. Bar = 10 μm. (B) Quantification of microtubule phenotypes exemplified in (A) resulting from expression of wild type and each TUBB8 mutation at low, intermediate or high levels of expression. About 200 transfected cells expressing either wild type or mutant TUBB8 were examined in each of three separate experiments; the result shown is the mean percentage of cells assigned to each category (normal, abnormal or obliterated) ± s. d. The propensity of the TUBB8 mutations to confer microtubule obliteration follows the order V229A = R2K = M300I = M363T >S176L > R262Q = D417N.

We repeated these expression experiments using constructs in which we introduced three of the TUBB8 mutations into TUBB5 (also termed TUBB), a β-tubulin isotype that (unlike TUBB8) is broadly expressed in mammalian tissues, especially in the developing CNS 25. We found that wild type TUBB5-FLAG invariably became incorporated into a normal microtubule network, while expression of S176L, M363T and R262Q in the context of TUBB5-FLAG caused a similar range of abnormal microtubule phenotypes seen in parallel experiments done in the context of TUBB8-FLAG, but present at a much reduced frequency (Figure S7). We conclude that the in vivo expression of the TUBB8 mutants we discovered results in varying degrees of disruption of normal microtubule architecture, and that this is strongly influenced by the β-tubulin isotype context.

To assess the ability of the TUBB8 mutations to interfere with microtubule dynamics, we examined the consequences of their expression in the context of the S. cerevisiae TUB2 gene (Figure S8). When introduced into diploid yeast as heterozygous TUB2 mutations, we obtained strains bearing each mutation with the exception of S176L. Upon sporulation, we found that similar to D417N 26, haploid V229A and R262Q spores were also inviable, revealing significant disruption of microtubule function (Figure S9). However, haploid spores harboring R2K, M300I and M363T were all viable, albeit with a varying degree of growth impairment, demonstrating that these mutations are not loss-of-function and are likely to alter microtubule properties (Figure S9).

Compared to the control strain, R262Q and D417N increased resistance to the microtubule-destabilizing drug benomyl, reflecting stabilized microtubules in vivo. Conversely, the R2K, V299A, M300I and M363T mutations all decreased benomyl resistance, suggesting they dominantly destabilize microtubules in vivo (Figure S10A, B). Moreover, in cells expressing GFP-α-tubulin, astral microtubules in heterozygous V229A and R2K cells depolymerized nearly twice as fast and the rescue frequency was markedly reduced compared to control cells (Figure S10C). Although microtubules in R262Q cells displayed depolymerization rates similar to controls, the catastrophe and rescue frequencies were reduced and the time spent attenuated increased (Figure S10D). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the TUBB8 mutations dominantly alter microtubule stability, and that the consequences of each mutation on microtubule function reflect a combination of effects including misfolding, diminished heterodimer yield, compromised dynamics and an impact on the binding of one or more MAPs.

TUBB8 mutations impair spindle assembly

To establish the causal relationship between mutations in TUBB8 and the disease phenotype, we utilized mouse oocytes to study the role of TUBB8 during oocyte maturation. Following microinjection of wild type TUBB8 RNA at around 12h after GVBD, maturation was normal, with a clearly visible barrel-shaped spindle (Figure S11). In stark contrast, microinjection of any of the TUBB8 mutant RNAs resulted in maturation arrest and a misshapen spindle, as well as a marked reduction in the first PB extrusion rate (6%–33% dependent on the mutant RNA, versus 61±2.2% in the wild type control) (Figure S11 and Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Mutant TUBB8 RNAs affect spindle assembly in mouse and human oocytes.

(A) Compared with the wild type control, polar body extrusion rates in mouse oocytes injected with mutant RNA (Figure S11) was significantly decreased; the experiment was performed 3 times; error bars represent mean ± s. d. ** P<0.01, **P<0.001. Unpaired T-test. (B) Immunostaining of mouse oocytes 12h after GVBD. GV oocytes were injected with a higher (1000 ng/μl) concentration of wild type RNA (n=25), S176L mutant RNA (n=36) or D417N mutant RNA (n=28). (C) Immunostaining of human oocytes 16h after GVBD. GV oocytes were injected with a higher concentration (1000 ng/μl) of TUBB8 wild type (n=28), S176L mutant RNA (n=8) or D417N mutant RNA (n=7). The MI oocytes were stained to visualize chromosomes (Hoechst 33342; blue), spindles (β-tubulin; green) and TUBB8 (FLAG; red).

We repeated these experiments using a higher concentration (1000ng/μl) of wild type, S176L and D417N RNA. This resulted in severely or completely impaired spindle assembly with both mutant RNAs (Figure 4B); this perfectly mimics the phenotype of human oocytes in maturation arrest. We also tested the extent to which the tubulin isotype context contributes to these effects by microinjecting mouse oocytes with RNAs encoding either TUBB5 wild type or mutant RNAs encoding either S176L, R262Q or M363T TUBB5. In broad agreement with our TUBB5 transfection data in cultured cells (Figure S7), oocytes microinjected with either wild type or mutant TUBB5 RNAs had normal spindle morphology (Figure S12), demonstrating that the impaired spindle assembly phenotypes we observed are conferred by the mutations in the context of the TUBB8 isotype. Finally, to further validate the effects of the mutation, we microinjected TUBB8 S176L and D417N mutant RNAs into human GV oocytes. Consistent with the phenotypes observed in mouse oocytes, we found severely or completely impaired spindle assembly (Figure 4C).

DISCUSSION

Although the process of oocyte maturation has been extensively investigated in mouse 27, the nature of mutations leading to human oocyte maturation arrest was previously unknown. Here we identified multiple mutations in TUBB8, a β-tubulin isotype of hitherto undetermined function. These mutations interfere with human oocyte maturation and are either inherited paternally as an autosomal dominant or arise de novo (Figure 1 and Table 1). They are in several cases predicted to confer changes in the structure of the tubulin heterodimer (Figure S5). The mutations were found to affect α/β-tubulin heterodimer folding and assembly in vitro (Figure S6), to cause a spectrum of striking microtubule phenotypes upon expression in cultured cells (Figure 3), and to alter microtubule dynamics in vivo (Figure S10). Moreover, the TUBB8 mutations caused oocyte maturation defects upon expression in mouse and human oocytes that precisely mimic the disease phenotype (Figure 4). We infer that mutations in TUBB8 not only correlate with but also cause oocyte maturation arrest. Taken together, these results define TUBB8 as a key gene in human oocyte meiotic spindle assembly and maturation.

TUBB8 is uniquely expressed in human oocytes and early embryos, where it accounts for the vast majority of all the β-tubulin present (Figure S3). It follows that human oocyte spindles consist of microtubules polymerized from heterodimers containing a single preponderant β-tubulin isotype. This finding reinforces the hypothesis that different tubulin isotypes can confer unique properties on functionally distinct subsets of microtubules 28. The ability of mutant TUBB8 proteins to cause microtubule disruption upon expression in cultured cells as well as in the context of oocytes suggests a model in which a dominant and cumulative effect occurs upon incorporation of a critical proportion of mutant heterodimers into polymers, in many cases leading to increased instability and frequently to complete microtubule annihilation.

The fact that TUBB8 exists only in primates suggests that this gene has been selected to play a unique role in reproductive development in these species. The observation that males harboring mutations in TUBB8 are fertile is consistent with the finding that TUBB8 is not expressed in mature sperm, highlighting mechanistic differences that distinguish meiosis and spindle formation in primate males and females. Because of the high proportion (7/24) of TUBB8 mutations we found in infertile women with oocyte maturation arrest, we infer that mutations in this gene account for a significant percentage of such cases. The existence of genetically unexplained families without mutation in TUBB8 implies that defects in as yet undiscovered genes can also contribute to human oocyte maturation arrest. Finally, the data presented here provide the basis for diagnostic tools for the identification of female patients with mutations in TUBB8, as well as for the future development of targeted therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB943300, to Dr. Lei Wang), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81270747, 81571501 to Dr. Lei Wang), the 111 Project (B13016) to Dr. Lei Wang and by a National Institutes of Health grant (5R01GM097376 to Dr. Nicholas Cowan; R01GM094313 to Dr. Mohan Gupta and R01GM051487 to Dr. Eva Nogales). We thank Dr Qingyuan Sun, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for instruction in the manipulation of oocytes and related techniques.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: R.F., Q.S. and Z.Y. identified the mutations, and did mouse and human oocyte immnunostaing. G.T. did the heterodimer folding experiments and analyzed the consequences of expression of TUBB8 in cultured cells. A.L. and Y.F. did the analysis of microtubule dynamics in yeast. Y.K., X.S., S.Z., J.S., provided information and materials from afflicted families. B.L., M.Y., J.C. collected clinical information and provided patients’ oocytes. Y.X., R.Q., Z.S., M.L., H.S., Y.F., R.C., Q.L., and Q.X. extracted samples of DNA and RNA. L.G. analyzed exome sequencing data. H.W. provided fetal tissues. R.S. provided guidance for pyrosequencing experiments. R.Z. and E.N. analyzed the structural implications of mutations. L.J. and L.H. provided suggestions for the study. L.W. conceived and supervised most of the study. N.C. supervised experiments on heterodimer folding and TUBB8 expression experiments in cultured cells. M.G. supervised experiments on microtubule dynamics in yeast. L.W., N.C., M.G. and E.N. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Eppig JJ. Regulation of mammalian oocyte maturation. In: Adash PCKL, editor. The Ovary. San Diego: Elsevier/Academic Press; 1993. pp. 113–29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehlmann LM. Stops and starts in mammalian oocytes: recent advances in understanding the regulation of meiotic arrest and oocyte maturation. REPRODUCTION. 2005;130:791–9. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park JY, Su YQ, Ariga M, Law E, Jin SL, Conti M. EGF-like growth factors as mediators of LH action in the ovulatory follicle. SCIENCE. 2004;303:682–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1092463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eppig JJ. Coordination of nuclear and cytoplasmic oocyte maturation in eutherian mammals. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1996;8:485–9. doi: 10.1071/rd9960485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos MA, Kuijk EW, Macklon NS. The impact of ovarian stimulation for IVF on the developing embryo. REPRODUCTION. 2010;139:23–34. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jurema MW, Nogueira D. In vitro maturation of human oocytes for assisted reproduction. FERTIL STERIL. 2006;86:1277–91. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudak E, Dor J, Kimchi M, Goldman B, Levran D, Mashiach S. Anomalies of human oocytes from infertile women undergoing treatment by in vitro fertilization. FERTIL STERIL. 1990;54:292–6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53706-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichenlaub-Ritter U, Schmiady H, Kentenich H, Soewarto D. Recurrent failure in polar body formation and premature chromosome condensation in oocytes from a human patient: indicators of asynchrony in nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation. HUM REPROD. 1995;10:2343–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartshorne G, Montgomery S, Klentzeris L. A case of failed oocyte maturation in vivo and in vitro. FERTIL STERIL. 1999;71:567–70. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergere M, Lombroso R, Gombault M, Wainer R, Selva J. An idiopathic infertility with oocytes metaphase I maturation block: case report. HUM REPROD. 2001;16:2136–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.10.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levran D, Farhi J, Nahum H, Glezerman M, Weissman A. Maturation arrest of human oocytes as a cause of infertility: case report. HUM REPROD. 2002;17:1604–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.6.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmiady H, Neitzel H. Arrest of human oocytes during meiosis I in two sisters of consanguineous parents: first evidence for an autosomal recessive trait in human infertility: Case report. HUM REPROD. 2002;17:2556–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janke C. The tubulin code: molecular components, readout mechanisms, and functions. J CELL BIOL. 2014;206:461–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201406055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sirajuddin M, Rice LM, Vale RD. Regulation of microtubule motors by tubulin isotypes and post-translational modifications. NAT CELL BIOL. 2014;16:335–44. doi: 10.1038/ncb2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breuss M, Keays DA. Advances in Experimantal Medicine and Biology. In: Nguyen L, Hippenmeyer S, editors. Cellular and Molecular Control of Neuronal Migration. Springer Science+Busimess Media; Dordrecht: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahi-Buisson N, Poirier K, Fourniol F, et al. The wide spectrum of tubulinopathies: what are the key features for the diagnosis? BRAIN. 2014;137:1676–700. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tischfield MA, Cederquist GY, Jr, Gupta ML, Engle EC. Phenotypic spectrum of the tubulin-related disorders and functional implications of disease-causing mutations. CURR OPIN GENET DEV. 2011;21:286–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li R, Albertini DF. The road to maturation: somatic cell interaction and self-organization of the mammalian oocyte. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:141–52. doi: 10.1038/nrm3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe Y. Geometry and force behind kinetochore orientation: lessons from meiosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:370–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang R, Alushin GM, Nogales ABE. Mechanistic Origin of Microtubule Dynamic Instability and its Modulation by EB Proteins. CELL. 2015;162(4):849–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alushin GM, Lander GC, Kellogg EH, Zhang R, Baker D, Nogales E. High-resolution microtubule structures reveal the structural transitions in alphabeta-tubulin upon GTP hydrolysis. CELL. 2014;157:1117–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nogales E, Whittaker M, Milligan RA, Downing KH. High-resolution model of the microtubule. CELL. 1999;96:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shang Z, Zhou K, Xu C, Csencsits R, Cochran JC, Sindelar CV. High-resolution structures of kinesin on microtubules provide a basis for nucleotide-gated force-generation. ELIFE. 2014;3:e4686. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowan NJ, Lewis SA. Type II chaperonins, prefoldin, and the tubulin-specific chaperones. Adv Protein Chem. 2001;59:73–104. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)59003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breuss M, Heng JI, Poirier K, et al. Mutations in the beta-tubulin gene TUBB5 cause microcephaly with structural brain abnormalities. CELL REP. 2012;2:1554–62. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tischfield MA, Baris HN, Wu C, et al. Human TUBB3 mutations perturb microtubule dynamics, kinesin interactions, and axon guidance. CELL. 2010;140:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt JE, Lane SI, Jones KT. The control of meiotic maturation in mammalian oocytes. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2013;102:207–26. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416024-8.00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luduena RF. Are tubulin isotypes functionally significant. MOL BIOL CELL. 1993;4:445–57. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.5.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.