Abstract

The Drosophila Piwi protein regulates both niche and intrinsic mechanisms to maintain germline stem cells, but its underlying mechanism remains unclear. Here we report that Piwi cooperates with Polycomb Group complexes PRC1 and PRC2 in niche and germline cells to regulate ovarian germline stem cells and oogenesis. Piwi physically interacts with PRC2 subunits Su(z)12 and Esc in the ovary and in vitro. Chromatin co-immunoprecipitation of Piwi, the PRC2 enzymatic subunit E(z), lysine-27-tri-methylated histone 3 (H3K27m3), and RNA polymerase II in wild-type and piwi mutant ovaries reveals that Piwi binds a conserved DNA motif at ~72 genomic sites, and inhibits PRC2 binding to many non-Piwi-binding genomic targets and H3K27 tri-methylation. Moreover, Piwi influences RNA Polymerase II activities in Drosophila ovaries likely via inhibiting PRC2. We hypothesize that Piwi negatively regulates PRC2 binding by sequestering PRC2 in the nucleoplasm, thus reducing PRC2 binding to many targets and influences transcription during oogenesis.

Keywords: Piwi, Polycomb, oogenesis, germline stem cell, epigenetics, Drosophila

INTRODUCTION

The Drosophila ovary is an effective model to analyze the molecular regulation of tissue stem cells (Fig. 1A). Each functional unit of the ovary, called the ovariole, contains 2–3 germline stem cells and 2–3 somatic stem cells at its tip within the germarium (Fig. 1A)1. Genetic analyses have identified key genes, including piwi, involved in Drosophila ovarian germline stem cell maintenance2,3. To identify genes involved in Piwi-mediated regulation of germline stem cells, we previously conducted a genome-wide screen for piwi suppressors4 and isolated Corto5, which physically associates with Polycomb Group (PcG) proteins6–8. Furthermore, Piwi is required for PcG-mediated transgene silencing9–11. Therefore, we determined whether PcG proteins are involved in Piwi-mediated regulation of germline stem cell maintenance.

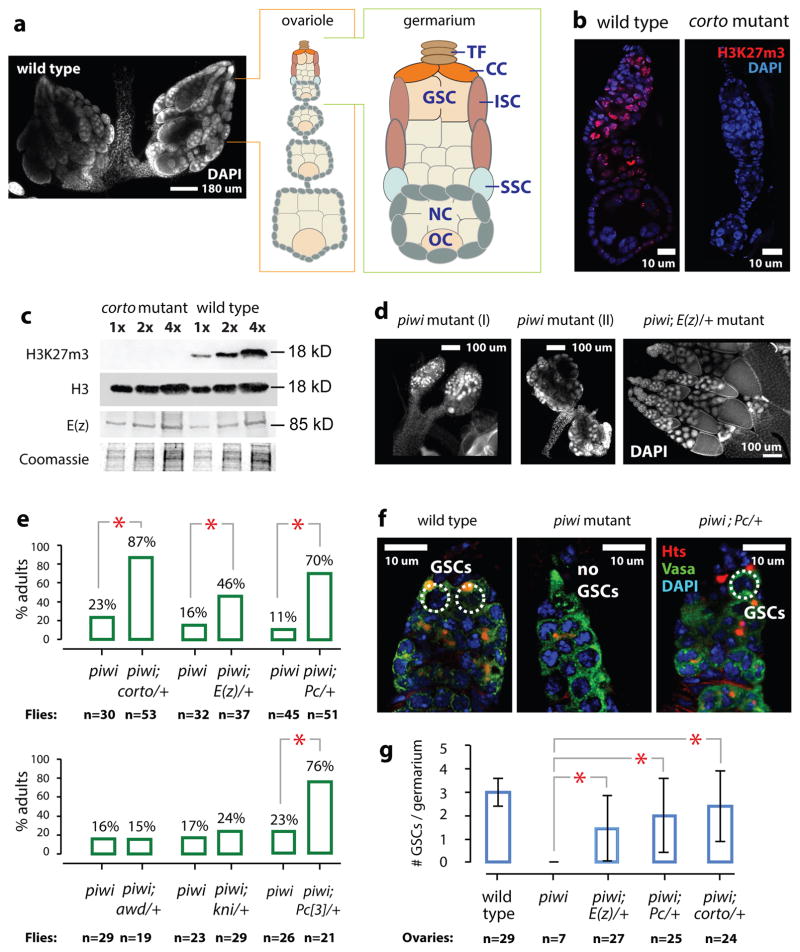

Fig. 1. Piwi, corto, and Polycomb Group genes genetically interact to regulate germline stem cells in Drosophila.

a) Left: DAPI image of wild type Drosophila ovaries, with an ovariole and a germarium illustrated. TF=terminal filament, CC=cap cells, GSC=germline stem cells, ISC=inner sheath cells, SSC=somatic stem cells, NC=nurse cells, and OC=oocyte.

(b) Confocal images of DAPI and H3K27m3 of wild type and corto mutant ovarioles.

(c) Two-fold serial dilutions of wild type and corto mutant ovarian extracts analyzed by immunoblotting to histone H3, H3K27m3 or E(z). Top portion of the gel analyzing E(z) was Coomassie-stained to show sample loading.

(d) DAPI images of piwi and the piwi; E(z)/+ mutant ovaries at the same magnification. Most piwi mutant ovaries are atrophic (I). Only 10–20% of ovaries contain rudimentary ovarioles (II).

(e) Percentages of females containing ovarioles.

(f) Confocal images of wild type, piwi mutant, and piwi;Pc/+ germaria stained for Hts and Vasa.

(g) Average numbers of GSCs per germarium in different genotypes. Error bars: standard deviations. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (p <0.001; Chi-square test).

The PcG proteins function in two major complexes, PRC1 and PRC2, which collaborate to inhibit RNA polymerase II (PolII) activity12,13. The enzymatic subunit E(z) of PRC2 methylates lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27m)14–17. PRC2 is known to function in germline establishment and maintenance in C. elegans18,19, and in testicular germline maintenance and oocyte fate specification in Drosophila20,21. PRC2 is recruited by Jarid2 to its targets22,23 and antagonized by (es)BAF24, demonstrating both positive and negative inputs to PRC2 function in maintenance and differentiation of stem cells. Here we report a novel epigenetic mechanism mediated by Piwi and PRC2 in regulating germline stem cells.

RESULTS

Piwi, corto, and Polycomb Group genes genetically interact

We previously showed that reducing corto activity partially rescued germline stem cell maintenance in piwi mutant ovaries5. This finding, together with the known interactions between Corto and PcG proteins6–8, led us to investigate whether corto mutations achieve this via affecting the PcG activity. We first analyzed H3K27 methylation in wild type and corto mutant ovaries. Immunofluorescence and immunoblotting revealed that H3K27m3 is drastically reduced in corto mutant ovaries (Fig. 1b–c). The Corto recombinant protein does not affect the histone methyltransferase activity of PRC2 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). These results suggest that Corto is required for H3K27 trimethylation but not directly influencing PRC2 methyltransferase activity in the ovary. We then analyzed whether reducing the activity of Pc (a subunit of PRC1 complex) would rescue the piwi mutant defects. This rescue was previously not observed5, presumably because the piwi2 chromosome used then contained the Irregular facets (If) mutation, which was used as a chromosome marker but somehow blocked the suppression. To avoid the potential effect of If and/or background mutation in the homozygous mutant, we used the piwi1/piwi2 trans-allelic combination without If to repeat our previous experiments on genetic suppression of piwi by corto, kni, mod(mdg4), or mi-2 mutations5. We observed partial but significant rescue of germline stem cells in the piwi1/piwi2 mutant by two mutant alleles of Pc and a mutant allele of E(z) (encoding a PRC2 subunit; Fig. 1d–e, Supplementary Fig. 1b). Transgenic shRNAs reducing Pc, E(z) or Esc protein levels in adult flies (Supplementary Fig. 1b, 1d, and 1f) also partially rescued oogenesis in ovaries in which Piwi was reduced by an shRNA targeting piwi mRNA for degradation (Supplementary Fig. 1c, 1e, and 1g). These data indicate that PRC2 and PRC1 negatively interact with Piwi to regulate oogenesis.

To further characterize the effects of PcG genes on ovarian germline stem cells and oogenesis, we analyzed germline stem cells by immunofluorescently labeling the Huli-Taishao (Hts) protein to visualize the spectrosome (a germline stem cell- and cystoblast-specific organelle), Vasa to mark germ cells, and Traffic Jam (Tj) to mark somatic cells. Reducing PcG activity by introducing one copy of Corto, E(z), and Pc mutations partially but significantly rescued germline stem cells (Fig. 1f and 1g), germarial organization (Supplementary Fig. 1h and 1i), and egg chamber development of the piwi1/piwi2 mutants (Supplementary Fig. 1j; homozygous PcG mutations are lethal). This rescue reflects genetic interactions between Piwi and PcG proteins.

Piwi, corto, and PcG interaction silences retrotransposons

Since a hallmark of the Piwi-piRNA pathway is its suppression of retrotransposon activities25–27, we determined whether PcG-Piwi interaction impacts transposon silencing. We examined whether corto, E(z), or Pc mutations affect Piwi-mediated retrotransposon silencing by RT-qPCR analysis of retrotransposon mRNAs. E(z) mutation suppresses all retrotransposons that are active in the germline, soma, or both lineages in piwi mutants (classified as Group I, III, and II, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 2a), whereas the corto mutation only suppressed somatically active (Group III) retrotransposons. Even more specifically, Pc only suppressed gtwin and ZAM in Group III. To exclude the possibility that the elevated expression of transposons in the mutants is due to increased soma-to-germline ratios in the mutant ovaries, we quantified Vasa (germ cell) and Tj (somatic cell) expression by RT-qPCR and immunoblotting, as normalized by Gapdh expression. The relative abundance of germ cells and somatic cells were approximately the same in all of the mutant ovaries (Supplementary Fig. 2b–c). Therefore, PcG proteins influence Piwi-mediated transposon silencing to various extents, underscoring the negative genetic interactions between Piwi and PcGs.

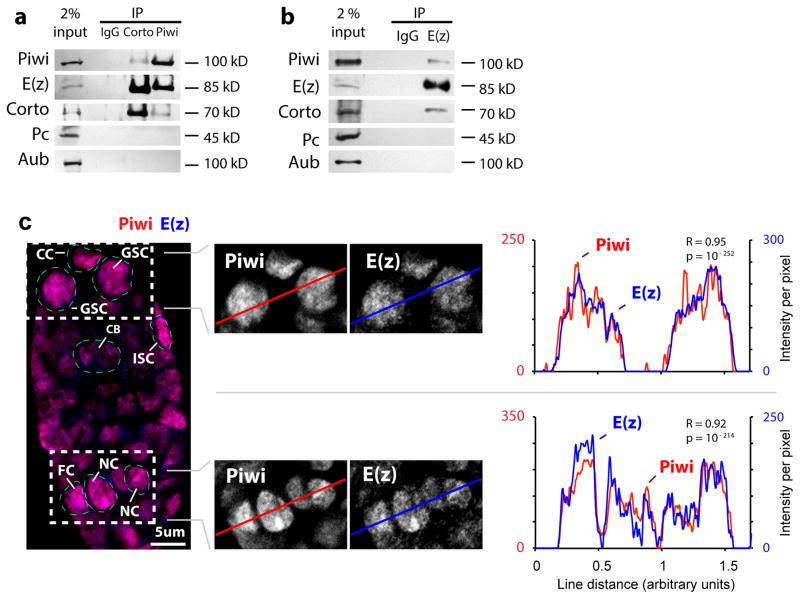

Piwi, Corto, and PRC2 physically interact in the ovary

To determine whether the genetic interaction between piwi and the PcG genes reflects the physical interaction of their proteins, we used anti-Piwi, anti-E(z) and a newly generated anti-Corto antibody (Supplementary Fig. 3a–b) to perform co-immunoprecipitation from ovarian extracts. Corto, Piwi and E(z) co-immunoprecipitate one another, yet the closest homolog of Piwi, Aubergine (Aub), did not co-immunoprecipitate with E(z) or Corto (Supplementary Fig. 2a–b). Nor does Pc, a PRC1 subunit, interact with Piwi or Corto. In addition, immunofluorescence microscopy of Piwi and E(z) revealed their highly overlapping pattern of co-localization within the nucleus, as demonstrated by line-scan profiles and high Pearson correlations for Piwi and E(z) signals (r=0.95, r=0.92; magnified sections in Fig. 2c). Furthermore, in vitro reconstituted PRC2 complex (Supplementary Fig. 3c) co-immunoprecipitated with the purified recombinant Piwi protein (Supplementary Fig. 3d), demonstrating direct PRC2-Piwi interaction (Fig. 3a) and supporting Piwi-PRC2 interaction in ovarian cells.

Fig. 2. Piwi binds to Corto and PRC2 in the ovarian extract.

(a) Corto and Piwi immunoprecipitates from wild type ovarian extract were analyzed by immunoblotting to Piwi, E(z) (of PRC2), Corto, Pc (of PRC1), and Aub.

(b) E(z) immunoprecipitates from wild type ovarian extract were analyzed by immunoblotting to Piwi, E(z) of PRC2, Corto, Pc of PRC1, and Aub.

(c) Confocal images of Piwi and E(z) immunofluorescence in a wild type germarium. GSC: germline stem cell, CC: cap cell, ISC: inner sheath cell, CB: cystoblast, NC: nurse cell, FC: follicle cell. Line profiles of immunofluorescence signals per pixel and Pearson correlation coefficients (R) indicate high correlation (with p values) of Piwi and E(z) signals.

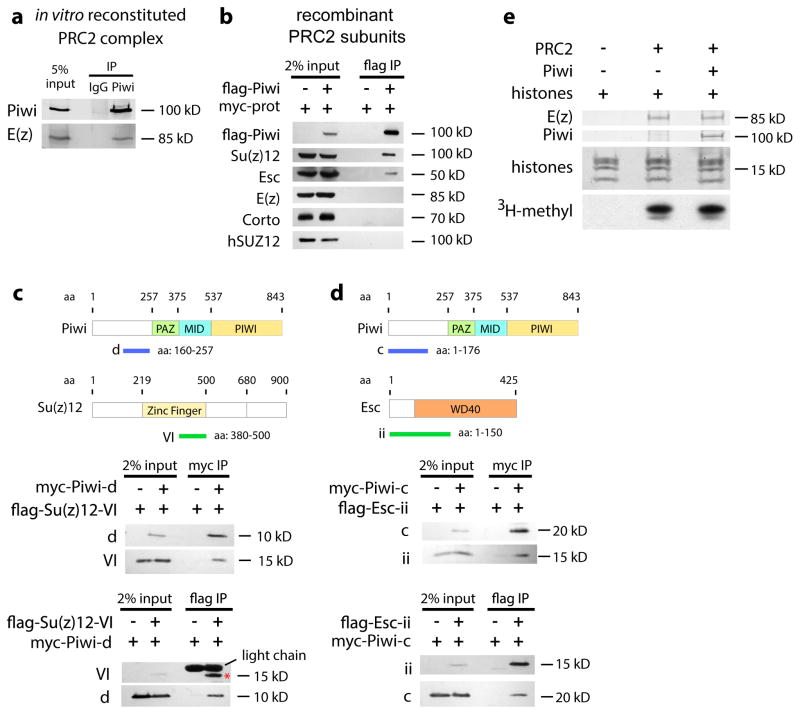

Fig. 3. Piwi binds to PRC2 in vitro but does not affect its HMTase activity.

(a) Recombinant Piwi was incubated with in vitro reconstituted PRC2 complexes and subjected to immunoprecipitation by anti-IgG and anti-Piwi antibodies, followed by immunoblotting.

(b) Full-length flag-Piwi was used to pull down full-length myc-Corto, myc-Esc, myc-Su(z)12, or myc-E(z) (collectively indicated as “myc-prot”) expressed in HEK293 cell extract. Bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting to the myc epitope.

(c) Myc-tagged Piwi-fragment d and flag-tagged Su(z)12-fragment VI were expressed in S2 cells and used to pull down each other.

(d) Myc-tagged Piwi-fragment c and flag-tagged Esc-fragment ii are expressed in S2 cells and used to pull down each other.

(e) In vitro reconstituted PRC2 complexes (represented by E(z) immunoblotting) were incubated with or without recombinant Piwi, and 3H-methylation signals were analyzed by radiography.

We next investigated which PRC2 subunits interact with Piwi and Corto in the Drosophila ovary and human HEK293 cells. In HEK293 cells, Piwi separately co-immunoprecipitated Esc and Su(z)12, but not Corto, E(z), or endogenous human SUZ12 - a negative control (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, Piwi co-immunoprecipitated with E(z) from the ovarian extract, where all PRC2 subunits are present, but not from the HEK293 extract, where Esc and Su(z)12 are absent. Thus, Esc and Su(z)12 mediate interaction between Piwi and PRC2.

We then used HEK293 and Drosophila S2 cells to identify domains of Piwi, Su(z)12 and Esc that mediate the interactions. Residues 160-257 of Piwi (fragment d in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3e) interact with residues 380-500 of Su(z)12 (fragment VI in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3f). Residues 1-176 of Piwi (fragment c in Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3g) interact with residues 1-150 of Esc (fragment ii in Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3h). Therefore, the N-terminal domain of Piwi interacts with Esc and Su(z)12. Since this domain also binds to Tudor family members28–31, it may act as a scaffold for interaction with Piwi partners.

The Piwi-interacting region of Su(z)12 falls inside the C2H2 zinc finger domain that interacts with nucleic acids. The Piwi-interacting domain of Esc corresponds to the N-terminal region of the WD40 domain that binds to H3K27m3 and propagates H3K27m3 through mitotic cycles32. To investigate whether Piwi regulates the H3K27 tri-methylation activity of PRC2, we purified recombinant Piwi protein and recombinant PRC2 complex for the in vitro methyltransferase assay. Piwi does not affect the enzymatic activity of PRC2 (Fig. 3e).

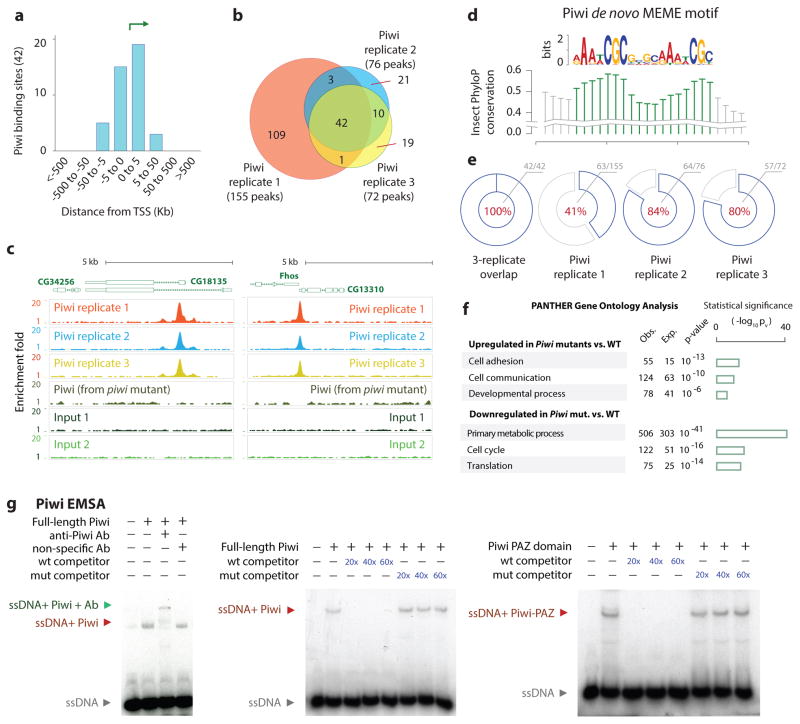

Piwi binds DNA via evolutionarily conserved sequence motif

The interaction between Piwi and PRC2 prompted us to investigate genome-wide binding of Piwi in ovarian cells. Although the Piwi-piRNA complex was shown to bind to specific genomic sites, such sites have not been definitively mapped genome-wide33–35. We generated a new anti-Piwi antibody capable of chromatin immunoprecipitation (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c) to map Piwi binding sites in the ovarian genome. We analyzed biological triplicates of Piwi ChIP-Seq from wild type ovarian cells, with biological triplicates of Piwi ChIP-Seq in piwi mutants as a negative control (Supplemental Methods; Fig. 4a). We used QuEST peak caller36 to identify 155, 72 and 76 Piwi enrichment peaks relative to input. Piwi peaks highly overlap across replicates, with 42 shared peaks (Fig. 4b; binomial p-value p<10−16). These peaks are enriched at the transcription start sites (Fig. 4a, 4c). De novo MEME motif analysis of the peaks revealed an enriched motif [a/g]AA[t/a]CGC[4 nt spacer][a/g]AA[t/a]CGC, consisting of two [a/g]AA[t/a]CGC direct-repeat cores separated by four nucleotides (Fig. 4d) thereafter called the Piwi Binding Motif (PBM). PBM was enriched across all three Piwi ChIP-Seq replicates and present in all 42 shared peaks (Fig. 4e). Increased phylogenetic conservation scores at the motif cores (Fig. 4d) support its functional importance.

Fig. 4. Genome-wide Piwi binding patterns and Piwi EMSA.

(a) Distribution of Piwi-bound regions relative to TSS.

(b) Venn diagram showing overlaps between the triplicates of Piwi ChIP-Seq peaks.

(c) Representative Piwi binding patterns at the CG34256 and Fhos genes in wild type and piwi mutant ovaries.

(d) Sequence motif enriched within Piwi peaks identified using MEME tool. Conservation using PhyloP scores is shown.

(e) Pie charts indicate recovery of PBM within Piwi ChIP-Seq peaks: 100% (42/42) of 3-way replicated overlapping sites, 41% (63/155) in replicate 1, 84% (64/76) in replicate 2, and 80% (57/72) in replicate 3.

(f) Gene Ontology terms of the genes that were up- or down-regulated by the piwi mutations; triplicate RNA-Seq samples were used. The bar graphs representing −log of p-values.

(g) EMSA analysis of Piwi binding to the PBM in 32P-labeled oligos. Red and green arrows indicate a shift and a super-shift, respectively.

To determine whether PBM indeed possesses higher Piwi binding affinity, we performed in vitro EMSA analysis (Fig. 4g). Purified recombinant Piwi protein binds to PBM-containing sequences in the Fhos locus, the Srp intron, and the CG18135 promoter but not their mutant forms (Supplementary Fig 4e). Moreover, Piwi exhibits stronger binding to the single-stranded sequences (Supplementary Fig. 4f). This binding is piRNA-independent, as demonstrated by the RNase A and H treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4f). In addition, only anti-Piwi antibody, but not other antibodies, resulted in a super-shift in EMSA (left panel, Fig. 4g). Using the Fhos sequence as an example, this binding can be inhibited by the unlabeled wild type oligo, but not the mutant sequence as a competitor to the labeled sequence (middle, Fig. 4g). These results indicate the specific binding of Piwi to its genomic targets via PBM.

Because the PAZ domain in Piwi binds to piRNA, we tested it for DNA binding by the above EMSA. Indeed, it binds to DNA (right, Fig. 4g), which indicates that Piwi PAZ domain likely binds to the PBM in vivo. However, we could not detect Piwi enrichment at the piRNA target sites such as the gypsy locus (data not shown). This might indicate that the PBM- and piRNA-mediated Piwi binding is mutually exclusive and that piRNA-mediated Piwi binding to the genome is too weak to be enriched under our ChIP-seq condition.

DNA motif-binding by Piwi does not regulate gene expression

To investigate the role of Piwi in regulating gene expression in ovarian cells, we performed triplicate RNA-Seq in piwi1/piwi2 and wild type fly ovaries. RPKM expression values were highly consistent within triplicates (R2=0.99; Supplementary Fig. 5a–b), indicating high reproducibility of gene expression data. We identified 899 statistically up-regulated genes and 1,036 down-regulated genes in the piwi mutant using a t-test and a p-value cutoff of 0.001 (Supplementary Fig. 5c). PANTHER Gene Ontology analysis37 showed that genes up-regulated in piwi mutant cells were modestly enriched for cell adhesion and developmental processes (Fig. 4f), and genes down-regulated in piwi mutant cells were highly enriched for primary metabolism, translation and cell cycle (Fig. 4f). Importantly, the expression of genes bound by Piwi is not strongly affected in the mutant, suggesting that genomic Piwi binding may not have a strong influence on gene expression.

Although Piwi binding is observed at the promoter regions, it is not strongly associated with nucleosome-bound DNA (Supplementary Fig. 4d) or promoters marked by H3K4m3 or H3K27m3. Most of the nuclear Piwi is not bound to DNA or chromatin. Thus, Piwi may regulate genes indirectly via its association with PRC2 complexes that are not bound to chromatin.

Piwi negatively regulates PRC2 binding to chromatin

Given the interactions between Piwi and PcG proteins and participation of Piwi in PcG-mediated transgene silencing9–11, we investigated whether Piwi regulates PRC2 binding to chromatin and H3K27 methylation by analyzing the total E(z) level, the E(z) binding to the genome, and genomic H3K27m3 profile in wild type and piwi mutant ovarian cells. Immunoblotting analysis indicates that the piwi mutation does not affect the total E(z) protein level in ovarian cells (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Next, we conducted four biological replicates of E(z) ChIP-Seq using a new anti-E(z) antibody (Supplementary Fig. 6b–c) and three biological replicates of H3K27m3 ChIP-Seq for wild type and the piwi mutant ovarian cells. E(z) and H3K27m3 showed genome-wide co-localization in both wild type and mutant ovaries (Fig. 5a). The shared regions had higher enrichment scores as compared to regions unique to each dataset (Supplementary Fig. 7), indicating threshold effects rather than true differences in Piwi binding. Of note, H3K27m3-associated regions were highly enriched for genes encoding transcription factors or involved in developmental processes (Fig. 5f).

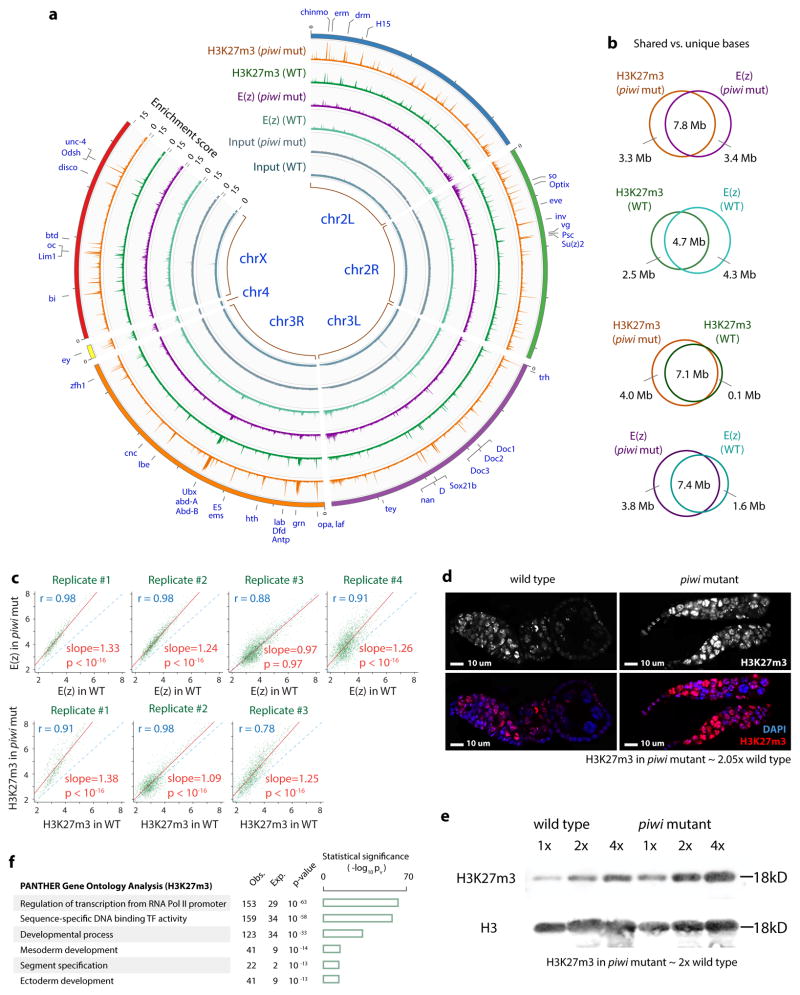

Fig. 5. Piwi inhibits PRC2 binding to chromatin and PRC2-mediated H3K27 tri-methylation.

(a) Circos plot shows H3K27m3 and E(z) binding patterns (enrichment scores calculated by ChIP-Seq counts within non-overlapping 10 Kb bins) in wild type and piwi mutant ovarian cells. Selected genes/peaks are indicated.

(b) Venn diagrams show overlaps of enriched regions between indicated ChIP-Seq datasets.

(c) Replicates of E(z) and H3K27m3 ChIP-Seq data in wild type and piwi mutant were compared.

(d) Confocal images of H3K27m3 and DAPI of wild type and piwi mutant ovarioles. H3K27m3 signals (normalized to DAPI signals) in piwi mutant were ~2-fold of wild type.

(e) Two-fold serial dilutions of histone extract from wild type and piwi mutant ovaries analyzed by immunoblotting to H3K27m3 and H3. H3K27m3 signals (normalized to H3 signals) in piwi mutant were ~2-fold of wild type.

(f) Gene ontology analysis of gene targets bound by H3K27m3. The bar graphs representing −lg of p-values.

We then examined the effects of Piwi on E(z) and H3K27m3 enrichment on chromatin. E(z) and H3K27m3 localization across the genome is not changed in piwi mutants ovaries (Fig. 5a–b); however, the E(z) level was uniformly 25–33% higher in piwi mutants in three out of four replicates (Fig. 5c). To confirm this analysis, we compared the levels of E(z) and H3K27m3 in wild type and the piwi mutant ovarian cells using immunofluorescence microscopy, immunoblotting, and ChIP-qPCR. The H3K27m3 immunofluorescence and immunoblotting signals were 2 fold higher in the piwi mutant than in wild type cells (Fig. 5d–e), and H3K4m3 signals were unaffected by the piwi mutations (Supplementary Fig. 6e). E(z) and H3K27m3 levels at individual PRC2 genomic targets were also significantly higher in the piwi mutant (Supplementary Fig. 6c–d). These results confirm our findings from ChIP-Seq that Piwi negatively regulates PRC2 binding to chromatin and H3K27m3 levels. Together with our biochemical results, these findings indicate that the association between Piwi and PRC2 likely occurs away from the chromatin and in the nucleoplasm. We therefore propose that Piwi binds to PRC2 in the nucleoplasm to compete against PRC2 binding to chromatin.

Although Piwi binding may not have a strong influence on gene expression, Piwi-mediated inhibition of PRC2 likely affects genes that are important for germline stem cells and oogenesis. RNA-seq analysis of PRC2-bound genes in wild type and the piwi mutant ovarian cells reveals that 27 of the 202 down-regulated genes affect germline formation as compared to only 12 of the 354 up-regulated genes with germline function (p =0.01; Supplementary Fig. 8). Further, the 12 up-regulated genes affect germline only when they were down-regulated, but not when they are up-regulated (Supplementary Fig. 8). Therefore, wild-type Piwi likely inhibits PRC2 activities to promote expression of the 27 of the PRC2-bound genes. A notable PRC2-bound gene down-regulated by the piwi mutations is pum, which is required for germline stem cell division1,3.

Piwi-PcG interaction influences RNA PolII activities

To investigate whether reduced PRC2 binding to chromatin and reduced H3K27m3 promote RNA PolII transcription, we profiled genomic RNA PolII localization by ChIP-Seq in ovarian cells from wild type (four replicates), piwi (triplicate), piwi; E(z)/+ (four replicates), piwi; Pc/+ (four replicates), and piwi; corto/+ (four replicates) mutants. Representative PolII tracks at the crib locus show a typical PolII localization pattern (Fig. 6a). PolII ChIP-Seq replicates within the same genotype were normalized and compared to each other, showing high correlation coefficients (R2 ~0.8), and supporting good reproducibility of RNA PolII binding signals (Supplementary Fig. 9).

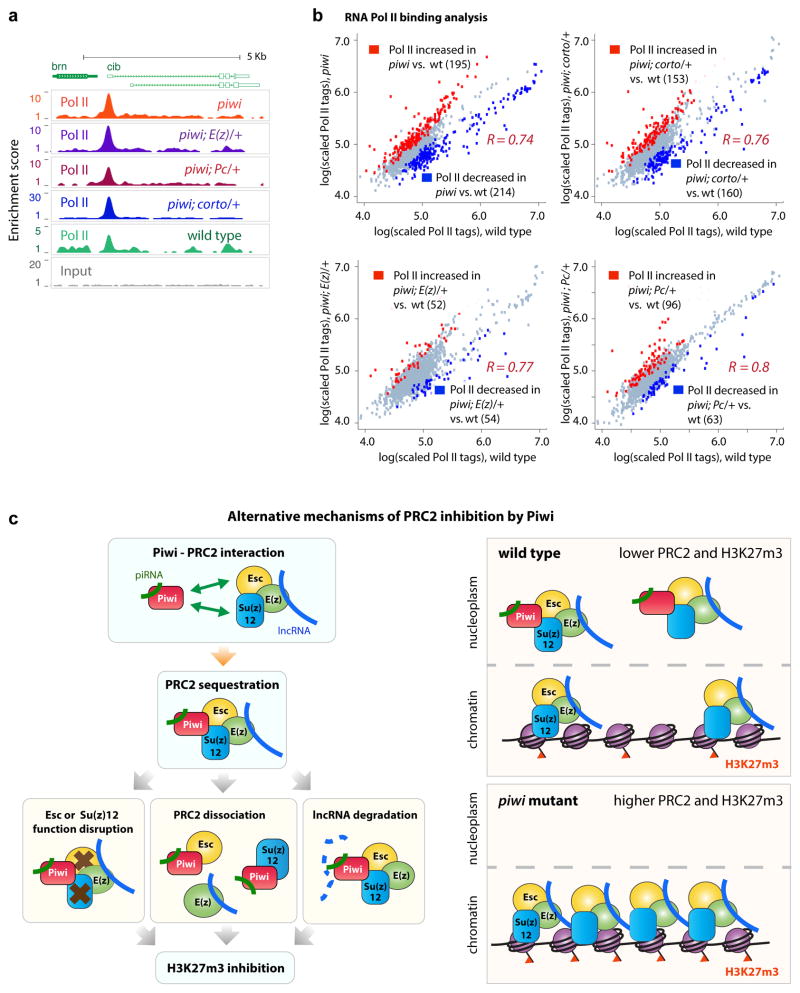

Fig. 6. RNA Pol II binding analyses in wild type and mutant ovaries.

(a) Representative Pol II binding and input signals at the cib locus.

(b) Comparisons of RNA Pol II binding intensities in four mutants vs. wild type across 1551 RNA Pol II binding regions. Each data point represents the lg-transformed average of replicate data. Pearson correlation values R between mutants and wild type strain signals were calculated. Red dots conveys increase of Z ≥ 1.5; blue for decrease of Z ≤−1.5, in mutants.

(c) PANTHER analyses of genes near RNA Pol II peaks with differential RNA Pol II levels. Obs.=observed. Exp.=expected. p-values indicate statistical significance of the enrichment.

(d) Proposed mechanisms of Piwi-mediated inhibition of PRC2. For details, see text.

Comparison between the wild type and the mutant replicates revealed 195 genes with statistically increased RNA PolII and 214 genes with decreased RNA PolII levels in the piwi mutant (Fig. 6b). However, repeat sequences do not show significant changes in the mutant. Overall, our analysis indicates that RNA PolII levels in the piwi mutant differs most significantly from that in wild type, followed by piwi; corto/+, piwi; E(z)/+ and piwi; Pc/+, (Fig. 6b). This pattern supports the idea that Piwi-PRC2 interaction influences RNA PolII activity and that PcG genes E(z) and Pc partially rescue the effects of piwi mutations on RNA PolII activity.

We next determined which genes are influenced by Piwi-PcG protein interaction. Although no particular type of genes shows preferentially decreased RNA PolII binding in the mutants, ‘protein folding’ and ‘response to stress’ genes (Fig. 6c) show preferentially increased PolII binding in the mutants. Our analysis revealed that Piwi mutations likely affect genes related to cellular stress response and translation. Mutations in Corto, E(z) and Pc can partially attenuate Pol II binding changes in piwi mutants, consistent with the involvement of PRC1 and PRC2 in regulation of RNA PolII binding. Collectively, our results indicate that Piwi indirectly influences RNA PolII binding at hundreds of genes in the Drosophila ovarian cells partly by negatively interacting with the PcG mechanism.

DISCUSSION

There are two major epigenetic repression mechanisms that involve histone modification—the HP1-mediated and the PcG-mediated mechanisms. We showed previously that Piwi is involved in the HP1-mediated mechanism whereby the Piwi-piRNA complex recruits HP1 and H3K9 methyltransferase to genomic sites for epigenetic regulation34,35,38,39. Here, we further demonstrate that Piwi negatively regulates Polycomb Group proteins and tri-methylation of H3K27. The Piwi-PRC2 interaction appears to occur mostly, if not exclusively, in the nucleoplasm, sequestering PRC2 away from its chromatin targets. This leads to a genome-wide reduction of H3K27m3 levels that influences the transcription by RNA PolII. This negative regulation represents a novel mechanism of epigenetic programming required for germline stem cell self-renewal, oogenesis, and transposon suppression. This regulation may be germ cell-specific, since over-expression of Piwi in all somatic cells did not result in observable defects40, therefore possibly does not affect PRC2 function. Our study, in addition to the reported antagonistic interaction between (es)BAF and PRC224, demonstrates the importance of inhibiting PRC2 binding to the genome for the fine-tuning of chromatin levels of H3K27m3 in the ovarian cells. While our study highlights the cooperation of PRC1 and PRC2 for their interaction with Piwi in regulating germline stem cell maintenance (Fig. 1e–g), PRC1 and PRC2 can exhibit different effects on germ cell development. For example, reduction of PRC1 activities by Pc knockdown does not markedly affect germ cells, yet reduction of PRC2 activities by E(z) knockdown drastically affects germline stem cell differentiation or oocyte-to-nurse cell specification21,41. These differences reflect that different protein composition of the PRC1 and PRC2 complexes render them overlapping but not identical functions.

Our in vitro and in vivo analyses also indicate that Piwi can bind to DNA independently of piRNAs and that this function appears to be separate from its PRC2 inhibition activity. Whether Piwi binds to specific genomic sites has been a contentious issue33,42. Our analysis indicates that Piwi protein has ~72–155 binding peaks in the ovarian cells (Fig. 4a–b). This binding activity is apparently independent of piRNA and prefers single-stranded DNA as substrate (Supplementary Fig. 4f). While this mode of binding does not appear to be involved in PcG protein regulation and its role remains unknown, the similarity of the PBM to that in C. elegans43 indicates that this binding activity might be conserved across species.

We hypothesize that Piwi inhibits PRC2 binding to its genomic targets by sequestering PRC2 into the nucleoplasm. This is accomplished by Piwi associating with PRC2 subunits Su(z)12 and Esc (Figs. 2, 3, Supplementary Figure 3) independent of piRNA. In addition, this sequestration might lead to inhibition of H3K27 methylation, disassociation of PRC2 complex, or piRNA-mediated degradation of lncRNAs associated with PRC244,45 (Fig. 6d). Extensive biochemical, genetic, and genomic characterizations would be necessary to distinguish these possibilities.

ONLINE METHODS

Buffers

Buffer A is 10mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10mM KCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.34M sucrose, 10% glycerol, 1x protease inhibitors (Roche), 1mM DTT.

Buffer B is 3mM EDTA, 0.2mM EGTA, 1x protease inhibitors (Roche), 1mM DTT.

Buffer D is 20mM HEPES pH 7.9, 25% glycerol, 0.2mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1x protease inhibitors (Roche), 1mM DTT, and KCl concentrations at 300mM for protein extraction.

PBS is 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.4.

Triton-X-100 is abbreviated ‘T.’

EMSA buffer is 25mM Tris pH 8, 80mM NaCl, 35mM KCl, 0.5mM DTT.

Fly stocks

All fly stocks were raised at 20 °C; except the RNAi flies, which were raised at 25 °C. The piwi mutant animals are transheterozygous piwi1/piwi2; both are loss of function alleles, and 10–20% of piwi1/piwi2 have ovarioles. Wild type is w1118, corto mutations are transheterozybous 420 (from Frederique Peronnet) and L1, E(z) mutation is 63 (from Richard Jones), and Pc mutations are alleles 1 and 3. Other flies, listed in Supplementary Table 1, were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center or the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center. Fly crosses were made with parents at 4–8 days old. F1 generation at 4–5 days old (age matched) were analyzed for ovariole presence or harvested for immunofluorescence, immunoblotting, IP, or ChIP. Sample size of >20 was selected for statistical analysis. No randomization or blinding was used to determine animals were analyzed/processed.

Immunofluorescence

Dissected ovaries were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde/PBS, washed, and permeabilized in 0.5% T/PBS for 4 nights. The ovaries were then blocked with 2% BSA/PBS, incubated in primary or secondary antibody solutions overnight and washed with 0.2% T/PBS for > 2 hours. The ovaries were then DAPI-stained, washed, mounted in slides, and imaged with the Leica TCS SP5 Spectral Confocal Microscope.

Antibodies

The names, their source, and the dilution conditions are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Histone extraction

Dissected ovaries (> 50 pairs) were homogenized in 1.5ml tubes and proteins extracted for 10 minutes using 400mM KCl buffer D. Resultant pellets were extracted with 0.2M HCl overnight at 4 °C. The extract was neutralized by 1.5M Tris-Cl pH 8.8 and then analyzed by immunoblotting.

Image acquisition and quantitation

Confocal images were acquired with a Leica TCS SP5 Spectral Confocal Microscope, with equal intensity and exposure between samples when imaging the same protein of interest. Immunoblotting images were obtained with a Gel Logic 2200 Imaging System. Image quantification was accomplished by using the measure function of the software ImageJ to obtain total signals in the region or band of interest and then standardizing the background-subtracted signals to either Coomassie band signals for immunoblotting or DAPI image signals for immunofluorescence.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIZOL, 2ug of RNA reverse transcribed (by high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit, Applied Biosystems) and qPCR analyses were performed with the iQ SYBR Green Supermix in the CFX96 system (Bio-Rad). Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Protein extraction and immunoprecipitation

Dissected ovaries (> 50 pairs) were homogenized in 1.5ml tubes and proteins extracted using 300mM KCl buffer D. Equal amounts of ovarian extract were incubated with antibodies overnight, followed by incubation with Protein A-conjugated Dynabeads (Invitrogen) for 3 hours. Beads were then washed with 0.05% T/PBS, and immunoprecipitates eluted by 2X loading buffer.

Glycerol gradient fractionation

45ul or recombinant proteins or ovarian extract was laid on top of a 2 ml 10%–50% glycerol density gradient and then separated by 55,000 RPM centrifugation for 4 hours in a TLS-55 rotor (Beckman). 65-ul fractions were collected.

Protein pull down using HEK293 extract or S2 cell extract

HEK293 cells were transfected with DNA constructs (made in pcDNA 3.1(+); primers listed in Supplementary Table 4) using Lipofectamine2000 (Life Technologies). The Drosophila S2 cells were transfected with DNA constructs (made in pAMW or pAFW from Drosophila Genome Resources Center; primers listed in Supplementary Table 4) using Cellfectin II (Life Technologies). Twenty-four to forty-eight hours after transient transfection, the cells were washed and extracted with 300 mM KCl buffer D. Extract (diluted to 150 mM KCl) were incubated with anti-flag or myc antibody beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hours, washed with 0.05% T/PBS, and eluates collected for analysis.

Recombinant protein preparation, pull down, and in vitro histone methyltransferase

ORFs of E(z), Su(z)12, and Esc were cloned into pFastBac by the Bac-toBac N-His TOPO cloning kit (Life Technologies) for baculovirus generation via the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression systems (Life Technologies). N-terminal His tagged proteins were isolated by nickel beads from Sf9 extracts co-infected with E(z), Su(z)12, and Esc baculoviruses. Protein complex was reconstituted from the eluate and analyzed by Coomassie staining. HEK293 cells were transfected with flag-Piwi-pcDNA3.1(+). Flag-Piwi recombinant proteins were isolated from the HEK293 cell extract by flag beads (Sigma-Aldrich), washed, eluted with 0.2mg/ml 3xflag peptides (Sigma-Aldrich) at 28 °C, and analyzed by Coomassie staining. For pull down, 1ug of flag-Piwi proteins and 10ug of PRC2 complex was added in 150ul PBS 0.1% Triton-X-100 for 20-minute incubation at room temperature, and 2ul guinea pig anti-Piwi antibody was used. In vitro histone methyltransferase assay was performed according to Peng et al., 2009.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Dissected ovaries were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde/PBS, homogenized, and sonicated in the Bioruptor (Diagenode). ChIP procedure was performed according to Boyer et al. (2005), using 100–300 ug of chromatin per IP. ChIP-qPCR signals were calculated as %’s of input. Primer sequences are included in Supplementary Table 5.

EMSA assay

Full-length flag-Piwi proteins were isolated from HEK293 cell extract and PAZ domain were isolated from BL21 bacterial extracts. 10–40 ng of recombinant proteins were incubated with 10 fmol of P32-labeled (by T4 PNK from NEB) oligos in 10ul of EMSA buffer and 10% sucrose for 10 minutes and loaded on an 8% TBE gel. 0.5ul of purified antisera guinea pig anti-Piwi antibody, 2ug of non-specific IgG, or 5ug of HEK293 cell extract were used. Gel was run for 50 minutes at 120V and exposed to autoradiogram. Oligo sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Piwi ChIP-Seq analysis

Sequencing reads were mapped against the reference dm3 assembly (R5 assembly, Apr. 2006) using Novoalign read mapper (flags: -o SAM -o Sync -S 4000 -s 10 -p 7,10 0.4,2 -t 120 –k). We retained only unique-mapping reads for further analyses.

Piwi peaks were identified using QuEST peak caller36 using the following settings: (1) Transcription factor ChIP-Seq, (2) ChIP enrichment: 3, ChIP-to-background enrichment: 2, ChIP extension enrichment: 1.

De novo Piwi motif was identified using MEME46 and FIMO47 tools. 3-way Piwi overlapping sites were calculated using 200 bp distance cutoff.

RNA-Seq analysis

RNA-Seq reads from three wild type replicates and three Piwi mutant replicates were processed using DNANexus cloud platform, including mapping reads to RefSeq transcript annotation and calculation of RPKM values. We calculated Student’s t-test p-value for each gene using triplicate measurements in Piwi and Wt and reported up- or down- regulated genes using p-value cutoff of 0.001. Differentially expressed genes were further analyzed using Gene Ontology system PANTHER37.

H3K27m3 and E(z) ChIP-Seq analysis

Sequencing reads from H3K27m3 ChIP-Seq, E(z) ChIP-Seq or input datasets were mapped against the reference dm3 assembly (R5 assembly, Apr. 2006) using Novoalign read mapper (flags: -o SAM -o Sync -S 4000 -s 10 -p 7,10 0.4,2 -t 120 –k). We retained only unique-mapping reads for further analyses.

We used QuEST peak caller36 to identify genomic regions where H3k27m3 or E(z) signals were enriched. When running QuEST we used the following set of parameters: (1) Histone ChIP-Seq, (2) ChIP enrichment: 3, ChIP-to-background enrichment: 1.5, ChIP extension enrichment: 1.

H3K27m3 or E(z) scatter plots were generated by calculating the number of reads falling into H3K27m3 (or E(z)) regions and normalizing to the expected counts before plotting. Linear fit was performed in R (R Development Core Team, 2008).

Circos plots

Circos plots were generated using Circos tool48 by (1) calculating ChIP-Seq reads in 10,000 bp bins, (2) converting counts to enrichment scores by normalizing the counts by the expected read counts within 10,000 bp bins, (3) applying Circos tool to the resulting enrichment scores.

RNA Pol II analysis

RNA Pol II ChIP-Seq datasets were generated for the following fly strains: Wild type (4), piwi mutant (4) with one replicate removed due to its very low correlation with other piwi replicates, piwi; Corto/+ mutant (4), piwi; E(z)/+ mutant (4), piwi; Pc/+ mutant (4) with one replicate not considered due to its very low correlation (<0.6) with the other three piwi; Pc/+ replicates.

1551 RNA Pol II binding peaks were first determined using the strongest Pol II ChIP-Seq dataset (piwi; Corto/+) using QuEST tool36. Then for each ChIP-Seq dataset we counted the number of RNA Pol II ChIP-Seq reads within +− 300 bps of each Pol II peak. We plotted replicate datasets after log-transformation of tag counts and calculated within-replicate correlations, which confirmed good experimental replication. For each mutant we designated one RNA Pol II dataset to calculate the scaling factor, necessary to average across the replicates:

Scaling factor = median (Pol II tags in replicate 2/Pol II tags in replicate 1).

Next, we adjusted Pol II tag counts in that replicate according to the scaling factor or used the original signals for the reference replicate. For each RNA Pol II binding region for each mutant we calculated its mean binding signal (by averaging scaled signals) and its sample variance (using scaled signals). We then calculated correlations of RNA Pol II binding signals between mutants (Supplementary Figure 5A) as well as between mutants and wild type strains (Supplementary Figure 5B).

To identify regions with evidence of differential RNA Pol II binding between a given mutant and a wild type strain (Figure 6B) we first scaled RNA Pol II signals between that mutant (e.g. piwi) and a wild type strain according to the formula:

The scaling factor was used to adjust mean and variance of the Pol II signal for that mutant. We then determined Pol II peaks that increased in strength in the mutant compared to wild type (‘Pol II increased’) and determined statistical significance of this change by calculating Z-scores and using appropriate cutoff (Z ≥ 1.5) to select regions showing increased Pol II binding in that mutant. Similarly, we determined Pol II peaks that decreased in strength in the mutant vs. the wild type (Z ≤−1.5). Each Pol II binding region was assigned to a nearby gene promoter and sets of sites showing statistically increased (or decreased) RNA Pol II binding signals were further analyzed using PANTHER Gene Ontology classification system to determine enriched gene sets in that mutant as compared to the wild type.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Jones for the E(z)63 fly, F. Peronnet for the corto420 fly, V. Pirotta for the Pc antibody, H. Siomi for the Piwi antibody, D. Godt for the Tj antibody, A. Fire and members of the Lin lab for assistance and discussions. We also thank H. Qi and J. Klein for experimental help, M. Reddivari for isolation of recombinant PRC2 complex, Z. Albertyn and C. Hercus for help with Novoalign. N. Neuenkirchen and X. Cui for critical reading. This work was supported by an NIH Pioneer Award (DP1CA174418) and the Mathers Award to HL and an NIH grant to JCP (R00-HD071011).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

JP and HL designed the project, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JP conducted all of the experiments except for those listed in the Acknowledgement. AV produced all bioinformatic results in the paper and participated in paper writing. NL did initial bioinformatics analysis that helped guiding the project.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Sequencing data were deposited to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (accession number PRJNA289709).

References

- 1.Deng W, Lin H. Asymmetric germ cell division and oocyte determination during Drosophila oogenesis. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;203:93–138. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)03005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox DN, et al. A novel class of evolutionarily conserved genes defined by piwi are essential for stem cell self-renewal. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3715–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin H, Spradling AC. A novel group of pumilio mutations affects the asymmetric division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1997;124:2463–76. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.12.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smulders-Srinivasan TK, Lin H. Screens for piwi suppressors in Drosophila identify dosage-dependent regulators of germline stem cell division. Genetics. 2003;165:1971–91. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smulders-Srinivasan T, Szakmary A, Lin H. A Drosophila Chromatin Factor Interacts With the piRNA Mechanism in Niche Cells to Regulate Germline Stem Cell Self-renewal. Genetics. 2010 doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.119081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kodjabachian L, et al. Mutations in ccf, a novel Drosophila gene encoding a chromosomal factor, affect progression through mitosis and interact with Pc-G mutations. EMBO J. 1998;17:1063–75. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez A, Higuet D, Rosset R, Deutsch J, Peronnet F. corto genetically interacts with Pc-G and trx-G genes and maintains the anterior boundary of Ultrabithorax expression in Drosophila larvae. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;266:572–83. doi: 10.1007/s004380100572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salvaing J, Lopez A, Boivin A, Deutsch JS, Peronnet F. The Drosophila Corto protein interacts with Polycomb-group proteins and the GAGA factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2873–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grimaud C, et al. RNAi components are required for nuclear clustering of Polycomb group response elements. Cell. 2006;124:957–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal-Bhadra M, Bhadra U, Birchler JA. Cosuppression in Drosophila: gene silencing of Alcohol dehydrogenase by white-Adh transgenes is Polycomb dependent. Cell. 1997;90:479–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80508-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal-Bhadra M, Bhadra U, Birchler JA. RNAi related mechanisms affect both transcriptional and posttranscriptional transgene silencing in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 2002;9:315–27. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuettengruber B, Chourrout D, Vervoort M, Leblanc B, Cavalli G. Genome Regulation by Polycomb and Trithorax Proteins. Cell. 2007;128:735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon JA, Kingston RE. Mechanisms of polycomb gene silencing: knowns and unknowns. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:697–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czermin B, et al. Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell. 2002;111:185–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuzmichev A, Nishioka K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Histone methyltransferase activity associated with a human multiprotein complex containing the Enhancer of Zeste protein. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2893–905. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller J, et al. Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell. 2002;111:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao R, et al. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science. 2002;298:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holdeman R, Nehrt S, Strome S. MES-2, a maternal protein essential for viability of the germline in Caenorhabditis elegans, is homologous to a Drosophila Polycomb group protein. Development. 1998;125:2457–67. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korf I, Fan Y, Strome S. The Polycomb group in Caenorhabditis elegans and maternal control of germline development. Development. 1998;125:2469–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eun SH, Shi Z, Cui K, Zhao K, Chen X. A non-cell autonomous role of E(z) to prevent germ cells from turning on a somatic cell marker. Science. 2014;343:1513–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1246514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iovino N, Ciabrelli F, Cavalli G. PRC2 controls Drosophila oocyte cell fate by repressing cell cycle genes. Dev Cell. 2013;26:431–9. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng JC, et al. Jarid2/Jumonji coordinates control of PRC2 enzymatic activity and target gene occupancy in pluripotent cells. Cell. 2009;139:1290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen X, et al. Jumonji modulates polycomb activity and self-renewal versus differentiation of stem cells. Cell. 2009;139:1303–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho L, et al. esBAF facilitates pluripotency by conditioning the genome for LIF/STAT3 signalling and by regulating polycomb function. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:903–13. doi: 10.1038/ncb2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aravin AA, Hannon GJ, Brennecke J. The Piwi-piRNA pathway provides an adaptive defense in the transposon arms race. Science. 2007;318:761–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1146484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson T, Lin H. The biogenesis and function of PIWI proteins and piRNAs: progress and prospect. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:355–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brennecke J, et al. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;128:1089–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Saxe JP, Tanaka T, Chuma S, Lin H. Mili interacts with tudor domain-containing protein 1 in regulating spermatogenesis. Curr Biol. 2009;19:640–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen C, et al. Mouse Piwi interactome identifies binding mechanism of Tdrkh Tudor domain to arginine methylated Miwi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20336–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911640106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vagin VV, et al. Proteomic analysis of murine Piwi proteins reveals a role for arginine methylation in specifying interaction with Tudor family members. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1749–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.1814809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu L, Qi H, Wang J, Lin H. PAPI, a novel TUDOR-domain protein, complexes with AGO3, ME31B and TRAL in the nuage to silence transposition. Development. 2011;138:1863–73. doi: 10.1242/dev.059287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margueron R, et al. Role of the polycomb protein EED in the propagation of repressive histone marks. Nature. 2009;461:762–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin H, et al. Reassessment of Piwi Binding to the Genome and Piwi Impact on RNA Polymerase II Distribution. Dev Cell. 2015;32:772–4. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang XA, et al. A Major Epigenetic Programming Mechanism Guided by piRNAs. Dev Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin H, Lin H. An epigenetic activation role of Piwi and a Piwi-associated piRNA in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2007;450:304–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valouev A, et al. Genome-wide analysis of transcription factor binding sites based on ChIP-Seq data. Nat Methods. 2008;5:829–34. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Thomas PD. PANTHER in 2013: modeling the evolution of gene function, and other gene attributes, in the context of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D377–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brower-Toland B, et al. Drosophila PIWI associates with chromatin and interacts directly with HP1a. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2300–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.1564307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin H, Yin H. A novel epigenetic mechanism in Drosophila somatic cells mediated by Piwi and piRNAs. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:273–81. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cox DN, Chao A, Lin H. piwi encodes a nucleoplasmic factor whose activity modulates the number and division rate of germline stem cells. Development. 2000;127:503–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan D, et al. A regulatory network of Drosophila germline stem cell self-renewal. Dev Cell. 2014;28:459–73. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marinov GK, et al. Pitfalls of Mapping High-Throughput Sequencing Data to Repetitive Sequences: Piwi’s Genomic Targets Still Not Identified. Dev Cell. 2015;32:765–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Billi AC, et al. A conserved upstream motif orchestrates autonomous, germline-enriched expression of Caenorhabditis elegans piRNAs. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sytnikova YA, Rahman R, Chirn GW, Clark JP, Lau NC. Transposable element dynamics and PIWI regulation impacts lncRNA and gene expression diversity in Drosophila ovarian cell cultures. Genome Res. 2014 doi: 10.1101/gr.178129.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe T, Cheng EC, Zhong M, Lin H. Retrotransposons and pseudogenes regulate mRNAs and lncRNAs via the piRNA pathway in the germline. Genome Res. 2015;25:368–80. doi: 10.1101/gr.180802.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grant CE, Bailey TL, Noble WS. FIMO: scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1017–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–45. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.