Abstract

A novel cell-based biosensing platform (Large-scale Homogeneous Nanoelectrode Arryas, LHONA) is developed using a combination of sequential laser interference lithography and electrochemical deposition methods. This enables the sensitive discrimination of dopaminergic cells from other types of neural cells in a completely non-destructive manner owing to its enhanced biocompatibility and excellent electrochemical properties. As such, this platform/detection strategy holds great potential as an effective non-invasive in situ monitoring tool that can be used to determine stem cell fate for various regenerative applications.

Keywords: nanoelectrode arrays, large-scale nanopatterning, dopaminergic differentiation, neural stem cells, electrochemical detection

Over the last decade, stem cell-based therapy has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy with significant implications for regenerative medicine due to the intrinsic ability of stem cells to differentiate into practically any given cell type.[1] For instance, human neural stem cells (hNSCs) are multipotent and have the ability to differentiate into both neurons and glial cells (e.g., oligodendrocytes, astrocytes and microglia).[2] As such, they hold immense potential for the treatment of neurological diseases/disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease and spinal cord injury.[3] In the case of PD, stem cell-based research has typically focused on the transplantation of stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons as PD is primarily caused by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) of the mid brain.[4] To identify and characterize these differentiated cells, which is critical to achieve prior to transplantation, fluorescence-based methods (e.g., immunostaining and FACS) and biomolecular analysis of the expression of biomarkers (DNAs/RNAs/proteins) are currently widely used. These techniques are highly sensitive and, as a result, can be used to precisely determine the biological characteristics of differentiated cells; however, they tend to be laborious, time-consuming and most importantly, involve destructive steps such as cell fixation or cell lysis, which prevents the subsequent use of these characterized cells for clinical applications. As such, to realize the full potential of stem cell-based therapies, there is an urgent need for techniques that can not only effectively identify stem cell fate but also do so in non-destructive and quantitative manner.

Addressing these challenges, we report a novel cell-based sensing platform (Large-scale Homogeneous Nanocup-electrode Arrays, LHONA) that is capable of achieving real-time and highly sensitive electrochemical detection of neurotransmitters that are produced from dopaminergic cells. As such, it can discriminate dopaminergic neurons from other types of cells in a completely non-invasive and label-free manner (Figure 1). In particular, LHONA is composed of distinct periodic cup-like nanostructures that were generated on an indium tin oxide electrode (ITO, 1.5cm × 1.5cm) via sequential laser interference lithography (LIL) and electrochemical deposition (ECD) methods. Owing to its unique nano-scale structure, LHONA has a number of advantages over other cell-based biosensors. First, recent studies have reported that nanostructured arrays can enhance cell functions via the spatiotemporal and dynamic rearrangement of focal adhesions and the cellular cytoskeleton.[5] As such, LHONA overcomes one of the major challenges faced by current cell-based biosensors- specifically, their dependence on cell adhesive molecules to promote cell anchoring to the electrode, which can adversely decrease the achievable sensitivity.[6] On the other hand, the three-dimensional nanostructures of LHONA are also highly preferred for detecting electrochemical signals owing to their capability to improve the selectivity, sensitivity and spatial resolution. Hence, by combining these aforementioned advantages, we demonstrated that LHONA can serve as an outstanding platform for the sensitive detection of both dopamine (DA) exocytosed from a model dopaminergic cell line (PC12) and dopaminergic neurons derived from hNSCs via the direct attachment/culturing of cells on the surface of LHONA in a biocompatible and non-destructive manner (Figure 1a). This enabled the sensitive discrimination of dopamine-producing neurons from other cell types including progenitor cells (hNSCs, neurospheres and premature neurons), non-dopaminergic neurons and other cell types (astrocytes and human dermal fibroblasts) (Figure 1b).

FIGURE 1.

(a) Schematic diagram representing superiority of large-scale homogeneous nanocup electrode arrays (LHONA) as a conductive cell culture platform which enhances major cell functions, as well as electrochemical sensitivity toward dopamine detection, both are extremely important for cell-based sensors. Picture is cell-based chip used for the detection of dopamine released from dopaminergic cells that is composed of ITO electrode, LHONA and the chamber for cell culture. Image above is the structural of LHONA characterized by scanning electron microscopy. (b) Detection strategy for the discrimination of dopaminergic neurons from other types of their progenitor cells using L-DOPA pretreatment and LHONA as the cell culture platform (working electrode) based on electrochemical method. Only cells capable of converting L-DOPA to dopamine can give distinct redox peaks which could be used as an indicator of the presence of dopaminergic neurons.

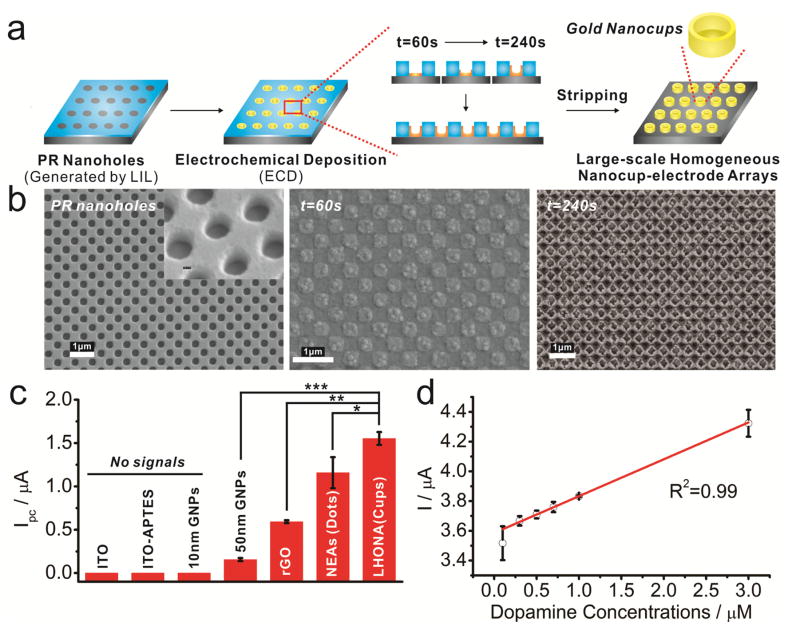

Figure 2a illustrates the experimental steps that were used to obtain the periodic metal nanostructures. Briefly, homogenous photoresist (PR) grid nanopatterns were first fabricated on the surface of ITO using LIL with different sizes and shapes (Figure 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1). Thereafter, the PR nanoholes were utilized as a template to deposit gold using the electrochemical deposition (ECD) method. By carefully adjusting the solution composition (e.g. concentration of gold chloride and type of surfactant) and the electrochemical parameters (e.g. voltage applied and time), which are related to the growth rate parallel or perpendicular to the direction of the current,[7] distinct cup-like or dot-like nanostructures were successfully generated on the entire ITO electrode (Figure 2b, Supplementary Fig. 2b). Besides the concentration of gold ions, deposition time was also a key parameter in controlling the geometry of the nanotopographic features. Patterns were formed as a thin film-like structure within a short period of time (t = 60s, Figure 2b) and finally, cup-like structures were generated when deposition time reached 240s, which was the best platform in terms of both its topographical characteristic (Figure 2b) and its electrochemical sensitivity toward DA detection (Supplementary Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

(a) Schematic diagram showing sequential steps to generate LHONA on ITO electrode via laser interference lithography (LIL) and electrochemical deposition method. (b) SEM images of (i) polymer nanohole template generated by LIL and electrochemically deposited gold nanostructures with different deposition time. (c) Intensities of cathodic peaks of dopamine obtained from cyclic voltammetry using different types of substrates and (Student’s t-test, N=3, *p<0.05, *p<0.01, *p<0.001). (d) The linear correlations between concentrations of dopamine and signal intensities at reduction potential of cyclic voltammetry.

Next, we compared the electrochemical performance of LHONA with other types of electrodes that use ITO as a supporting substrate in terms of sensitivity toward DA detection. As an initial proof-of-concept, we used a cell-free configuration where DA was detected in situ. At a concentration of 10 μM DA, the cathodic peak current (Ipc) were not detectable on bare ITO electrodes and ITO modified with 10 nm AuNPs (gold nanoparticles), while ITO-50nm AuNPs showed a very weak reduction peak (Ipc = 0.155 μA). On the other hand, ITO modified with reduced graphene oxide (rGO), which has previously been reported as an outstanding material for the detection of DA,[8] showed better performance (Ipc = 0.592μA). However, interestingly, LHONA substrates exhibited the most distinct redox peaks (Ipc = 2.25μA), which was 13.5 and 2.8 times higher than ITO-50nm Au NPs and ITO-rGO substrates (Figure 2c, Supplementary Fig. 4a). Remarkably, the reduction current of LHONA (nanocups) was even higher (59.6%) than homogeneous nanoelectrode arrays [NEAs (dot-like structure)] (Supplementary Fig. 2b, ii) generated using the same ECD method (Ipc = 1.41 μA), which is speculated to be due in part to the increased surface area, proving its excellent sensitivity for the electrochemical detection of DA. The redox peaks were constant and increased with increasing scan rates (20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 mV/s), proving that the cathodic peaks originated from DA and not from noise or other contaminants (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). Moreover, LHONA showed good linearity at both low (0.3–3μM, R2=0.99) and high concentrations (0–50μM, R2=0.986) of DA, with a limit of detection (LOD) of 100 nM (Figure 2d, supplementary Fig. 4b, supplementary Fig. 5c, d). Since the fabricated substrate (LHONA) showed excellent performance in terms of DA detection, which is superior to other transparent electrodes (GNP- and rGO-modified ITOs, homogeneous gold nanodot arrays), it is highly likely that LHONA will be the suitable material for effective in situ electrochemical detection of DA synthesized from dopaminergic cells in sensitive and non-invasive manner, which is at the ultimate goal of this study.

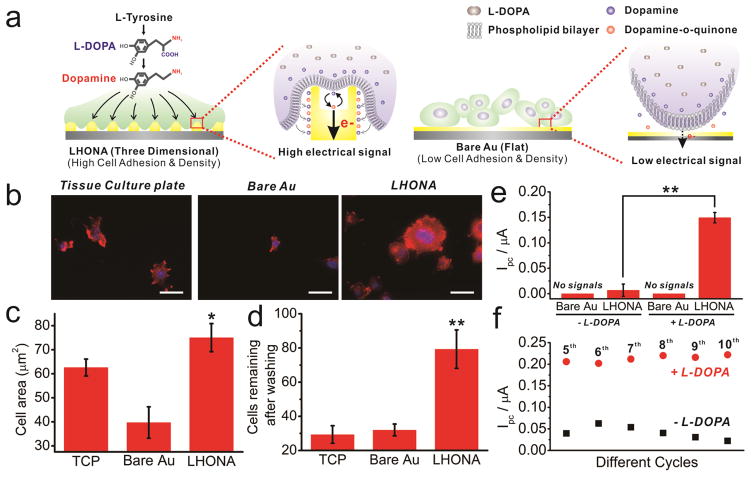

It is important to note that unlike typical biosensors, the electrode of cell-based biosensors must be highly biocompatible in order to promote cell attachment, growth, and subsequent secretion of the biomolecule of interest, which in this case is DA.[6a, 9] As such, we next investigated whether LHONA could act as an effective substrate for culturing neural cells. In particular, it was our hypothesis that the nanoscale topographic characteristics of LHONA (periodic and homogeneous) would contribute to the enhancement of cell adhesion, spreading and growth of the model dopaminergic cells (PC12) (Figure 3a).[5a, 5b, 10] Since PC12 cells are highly sensitive to the adhesion materials, as expected, cell spreading on bare gold and normal tissue culture plates (TCPs) was found to be highly restricted (Figure 3b). In contrast, interestingly, PC12 cells spread well on bare LHONA [without extracellular matrix (ECM) materials], where they exhibited a well-spread morphology throughout the entire surface that was similar to the cells on Matrigel-coated TCPs (Figure 3b, Supplementary Fig. 6). Remarkably, the total surface area of the cells spread on the LHONA was found to be 12.4% and 88.9% higher than that on TCPs and bare gold substrates (Figure 3c, Supplementary Fig. 7), respectively, and the number of cells remaining on the LHONA after washing was 270% higher than both TCP and bare gold substrates due to the enhanced cell adhesion (Figure 3d, Supplementary Fig. 7). Moreover, cell proliferation was found to be increased on LHONA substrate compared to bare gold substrates (Supplementary Fig. 8), proving that LHONA is an excellent platform for culturing and enhancing major functions of model dopaminergic neurons which will be suitable for electrochemical study over other types of substrates. These effects of nanostructured arrays on the cell functions became completely negligible after the modification of thick Matrigel layer on LHONA, proving that the enhancement of cell functions solely originated from the distinct nanotopographical features of LHONA (Supplementary Fig. 9).

FIGURE 3.

(a) Schematic diagram showing the interaction between cell membrane and the surface of electrodes that result in the increase of electrical signals of model dopaminergic cells on LHONA due to the enhanced cell spreading, adhesion and proliferation compared to flat (two dimensional) surface. (b) F-actin-stained fluorescence images of PC12 cells (Scale bar = 40μm), (c) analysis of cell surface area (cell spreading) and (d) cells remaining on the surface after washing for cell fixation which were calculated from F-actin-stained images of PC12 cells on three different substrates (Student’s t-test, N=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). (e) Ipc values of cyclic voltammogram achieved from PC12 cells on Bare Au and LHONA substrates. PC12 cells treated with L-DOPA prior to the electrochemical analysis indicated as “+ L-DOPA” while cells without L-DOPA indicated as “−L-DOPA”. (f) Ipc values calculated from cyclic voltammetric curves with different cycle numbers, which were obtained from PC12 cells on LHONA-M.

After confirming the superior characteristics of the LHONA in terms of biocompatibility, cyclic voltammetry (CV) was applied to detect DA released from PC12 cells attached to electrode. For this purpose, L-DOPA, a precursor which can be converted to DA by dopa decarboxylase (DDC), was added prior to the detection of DA to increase the amount of DA synthesized by the dopaminergic PC12 cells[6a, 9]. As expected, bare gold electrodes showed no redox signals regardless of treatment with L-DOPA (Figure 3e). This was hypothesized to be mainly due to the limited number of cells attached to the bare gold substrate, cell aggregation (less spreading), and limited growth, all of which indicated that the major functions of the PC12 cells were highly compromised (Figure 3b–d, supplementary Fig. 6–8). After modification with Matrigel, the morphology of the cells and their growth were significantly improved (Supplementary Fig. 9); however, no reduction and oxidation peaks appeared on the voltammogram owing to Matrigel blocking electron transfer to the surface of the electrode. We next attempted to use a reduced amount of Matrigel (4 times more diluted than normal concentration) to enhance the electron transfer from cells to the electrode; however, the diluted Matrigel modified on the gold substrate was found to be insufficient to improve cell spreading and proliferation. In contrast, interestingly, cells on LHONA showed clear reduction and oxidation peaks at −33 mV and 125 mV, respectively, proving its outstanding potential to be applied for in situ monitoring of DA released from dopaminergic cells (Figure 3e, supplementary Fig. 10). Remarkably, PC12 cells on diluted Matrigel-modified LHONA (LHONA-M) also showed strong redox signals of DA slightly higher than LHONA, which was clearly different from bare gold substrate (Supplementary Fig. 10). The peak-to-peak separation (Epa – Epc) was 158 mV, which was slightly higher than that of chemical DA (58mV), probably due to the cell membrane binding to the electrode that resulted in the increase of resistance. Next, to confirm the stability of electrochemical signals of DA released from PC12 cells, the signals from PC12 cells with or without L-DOPA pretreatment were compared based on the Ipc values of cyclic voltammogram with different cycle numbers. As shown in Figure 3e, the cathodic peaks from both groups were continuously appeared at around 0.21 μA and 0.04 μA for L-DOPA pretreated and non-treated PC12 cells, respectively, with increasing cycle numbers up to 10. The cathodic peak from L-DOPA pretreated PC12 cells (Ipc=0.222 μA) was 10 times higher than L-DOPA non-treated PC12 cells (Ipc=0.022 μA) at 10th cycle due to the increased amount of DA produced from cells via conversion of L-DOPA to DA, proving that the signals are highly stable and reliable which could be important for the determination of DA production capability of dopaminergic neurons (Supplementary Fig. 11). The electrochemical signals achieved from PC12 cells were also found to increase as the increase of cell numbers, indicating that LHONA is reliable platform capable of detecting dopamine produced from cells in quantitative manner (Supplementary Fig. 12). Finally, the DC amperometric method, a conventional tool that is useful for the simultaneous monitoring of changes in currents when applying a specific voltage,[9] was further utilized to validate electrochemical DA signals of dopaminergic cells that were measured using CV. As expected, a clear spike-like currents appeared on the i-t graph following addition of KCl (120mM) to trigger DA release while applying a cathodic voltage on PC12 cells, proving the presence of DA in PC12 cells which can be sensitively detected by LHONA substrate (Supplementary Fig. 13). Hence, it can be concluded that the fabricated large-scale homogeneous nanocup electrode arrays (LHONA) is a suitable material for the in situ monitoring of cellular signals, especially for the detection of DA from cells, mainly due to its outstanding electrochemical properties as well as its excellent biocompatibility.

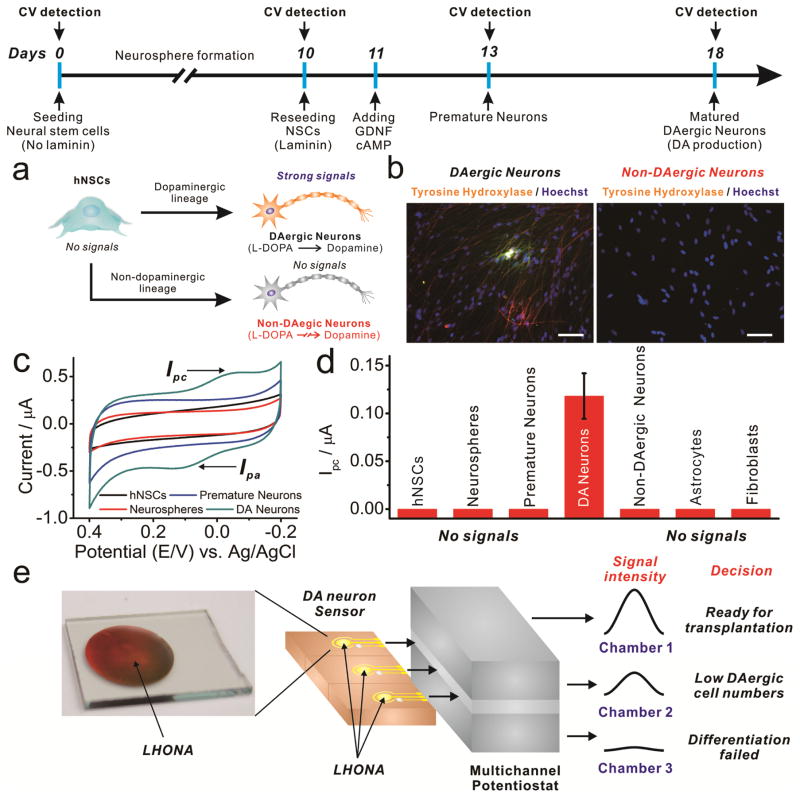

Next, we attempted to detect DA signals from hNSC-derived dopaminergic neurons since the hNSC-derived dopaminergic neurons are the actual source of transplantation which could be utilized for the treatment of DA-related psychiatric diseases/disorders.[4b, 11] The hNSCs can be converted into dopamine-producing neurons through neurosphere generation, which are clusters of NSCs that still retain multipotency capable of differentiating into different types of neural cells. Since the dopaminergic neurons are only specific cell lines which express DOPA decarboxylase (DDC) that enables conversion of L-DOPA to DA, by detecting electrochemical signals of DA synthesized from L-DOPA, we can obtain some clues that prove the presence of DA-producing neurons derived from NSCs simply, easily and precisely in completely non-invasive/non-destructive way.

To this end, hNSCs were differentiated into two different neurons- dopaminergic neuron and non-dopaminergic neuron and their electrochemical signals were compared with that of undifferentiated hNSCs, neurospheres and premature neurons (Figure 4a). ReNcell VM cell lines was chosen as a model stem cell line since it has been proven to be highly effective for the generation of dopaminergic neurons.[12] Similar to the PC12 cells, dopaminergic neurons derived from hNSCs spread well on the surface of LHONA as shown in Supplementary Fig. 14. To confirm the dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic differentiation of hNSCs, respectively, cells were stained with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), which is a representative marker of dopaminergic neurons.[13] As shown in Figure 4b, only cells that have undergone dopaminergic differentiation showed TH expression while non-dopaminergic cells failed to show any significant TH expression. A transcriptional activator for TH, Nurr 1, was also found to be highly expressed in the differentiated dopaminergic neurons when analyzed by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 15). After the validation of dopaminergic differentiation of hNSCs, cells were detached and re-seeded on the LHONA to confirm the difference between dopaminergic cells with other types of cells when analyzed by cyclic voltammetry. Remarkably, as hypothesized, only hNSC-derived dopaminergic neurons showed distinct redox peaks in voltammogram while its progenitor cells including hNSCs, neurospheres and even premature neurons failed to show any reduction/oxidation peaks (Figure 4c, Supplementary Fig. 16). Ipc values could only be calculated from dopaminergic neurons and was found to be approximately 0.13 uA, indicating that only dopaminergic neurons produced DA from externally added DA precursor (L-DOPA) via DDC (Figure 4d). To support these electrochemical results showing the ability of LHONA to detect dopamine and to distinguish dopaminergic neurons from other types of progenitor cells, the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed to confirm the dopamine release from L-DOPA pretreated dopaminergic neurons. We tested several different conditions: i) dopamine dissolved in medium, ii) medium collected from L-DOPA pretreated hNSCs, iii) L-DOPA non-treated dopaminergic neurons derived from hNSCs, and iv) L-DOPA pretreated dopaminergic neurons. As shown in Supplemetary Fig. 17, only dopaminergic neurons pretreated with L-DOPA showed a clear dopamine peak (iv) while other groups failed to show the same peak, which were consistent with the electrochemical results.

FIGURE 4.

(a) Schematic diagram showing the conversion of hNSCs into dopaminergic (DAergic) and non-DAergic neurons. (b) Fluorescence images of cells stained with tyrosine hydroxylase to identify DAergic and non-DAergic neurons derived from hNSCs. Scale bar = 100 μm. (c) Cyclic voltammogram achieved from cells undergoing differentiation into DAergic neurons (DA Neurons). Only completely matured DAergic neurons are showing distinct redox peaks as opposed to their progenitor cells (hNSCs, neurospheres and premature neurons). (d) Ipc values calculated from (c) and other types of cells (astrocytes and fibroblasts). ‘No signals’ means that Ipc values cannot be calculated due to the absence of cathodic peaks. (e) Possible strategy to use LHONA platform to confirm successful differentiation of NSCs into DAergic neurons and their DA production ability which could be critical for making decision on the transplantation of DAergic neurons generated ex vivo.

Thereafter, to confirm that only functional dopaminergic neurons can produce DA from L-DOPA, cells were intentionally damaged by incubation with DPBS for different periods of time (30 min, 60 min and 3 days) prior to the electrochemical detection. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18, the electrochemical signals were clearly detectable from the slightly-damaged or non-damaged cells (30 min) while cells incubated with DPBS for longer period of time (60 min) showed decreased reduction peaks that were 28.6% lower than that of 30 minutes at same reduction potential (Epc = −33mV). Finally, the voltammetric signals became completely negligible from the damaged dopaminergic neurons (cultured in DPBS for 3 days), proving that redox signals are only detectable from the viable/functional dopaminergic neurons, which will be highly useful to determine DA production ability of differentiated neurons prior to the clinical transplantation of them for replacing damaged/abnormal dopaminergic neurons that are responsible for many different types of neuronal diseases/disorders. Additionally, we also successfully confirmed that this distinct stable redox signals are not achievable from other type of similar neurons (non-dopaminergic neurons), glial cells (astrocytes) and completely different cells (human dermal fibroblasts) with same conditions (L-DOPA pretreatment), indicating that redox peaks are only specific to functional dopaminergic neurons (Figure 4d and Supplementary Fig. 19).

In conclusion, we have developed large-scale homogeneous nanocup electrode arrays (LHONA) for the effective detection of dopamine production from dopaminergic cell lines, as well as the monitoring of differentiation of hNSCs into dopaminergic neurons. LHONA bearing distinct cup-like nanostructures were successfully generated on transparent ITO electrode via two-step sequential process- laser interference lithography (LIL) and electrochemical deposition (ECD) method. The LHONA platform showed excellent performance in the detection of chemical DA at both low range of concentrations (0.3–3μM, R2=0.99) and high concentrations (0–50μM, R2=0.986), with the limit of detection (LOD) of 100nM, which was even higher than and other types of ITO-gold nanoparticle substrates, as well as the ITO modified with reduced graphene oxide (rGO). DA produced by model dopaminergic cells was found to be sensitively monitored on the LHONA due in part to its nanoscale pattern sizes and nanotopographical characteristics, which are large-scale periodic and homogeneous, that resulted in the enhancement of major functions of dopaminergic cells such as cell spreading, adhesion and proliferations, as well as the enhanced sensitivity toward DA detection. Furthermore, due to the excellent biocompatibility and electrochemical performance of LHONA, the differentiation of hNSCs into dopaminergic neurons was successfully monitored, which showed distinct redox peaks that were clearly distinguished from its progenitor cells (e.g. hNSCs, neurospheres and premature neurons), as well as the other cell types (e.g. non-dopaminergic neurons, astrocytes and fibroblasts). Since the destructive process such as cell lysis and fixation are totally excluded for detecting DA production and monitoring dopaminergic differentiation of hNSCs, the developed periodic nanostructured platform (LHONA) and the electrochemical detection strategy introduced here can hold huge potential for pre-clinical testing of newly-achieved dopaminergic neurons. Specifically, the LHONA platform can be useful for the assessment of the DA secretion from dopaminergic neurons derived from ESCs/iPSCs/NSCs/MSCs prior to the clinical usage, as well as for the optimization of protocols to generate more dopaminergic neurons from pluripotent/multipotent stem cells in easy, simple but precise way (Figure 4e). Hence, it can be concluded that this work advances cell-based biosensors as an effective non-destructive in situ monitoring tool for stem cell differentiation which can lead to more effective stem cell-based therapies for incurable diseases/disorders.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1. (a) Schematic diagram representing the set-up of laser interference lithography (LIL) to generate homogeneous photoresist nanostructures. (b) FE-SEM images of homogeneous nanoholes with size of (i) 150nm, (ii) 200nm, (iii) 500m, respectively, and nanolines with size of (iv) 200nm, (v) 300nm, respectively.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 2. (a) Schematic diagram representing two different deposition methods used in this study to fabricate large-scale homogeneous metal nanostructures. (b) SEM images of homogeneous nanostructures of gold nanodots with size of (i) 500nm and (ii) 350nm, respectively, and (iii) gold nanocups with size of 350nm. Structure (i) was fabricated by E-beam evaporation method while structure (ii) and (iii) were fabricated by electrochemical deposition method. Indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode was utilized as a supporting material for all substrates.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 3. (a) I-t curve used for the electrochemical deposition of gold through PR nanoholes with varying deposition time. (b) Voltammogram achieved from LHONA with different deposition time in the presence of 5μM DA. Arrows indicate that reduction (Epc) and oxidation peaks (Epa) are increasing with increase of the deposition time. (c) Current values obtained from (b) showing increase of peak currents at V (vs. Ag/AgCl) = 130mV. Student’s t-test was used for evaluating significance (*p<0.01, N=3), compared to the current values of 5μM DA achieved from LHONA with 120s deposition of gold.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 4. Voltammetric signals of dopamine achieved from (a) different types of substrates and (b) with different concentrations of dopamine (0.1 – 3 μM)

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 5. (a) Cyclic voltammeric curves with varying the scan rate and (b) its corresponding current values at reduction and oxidation potential showing linear correlations between scan rate and electrochemical signals. (c) Voltammogram achieved from LHONA (240s deposition) with varying DA concentrations from 0 to 50 μM and (d) linear correlations between the concentrations of DA and currents values at Epc.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 6. Fluorescence images of F-actin-stained PC12 cells on (a) Bare gold and (b) LHONA substrates without modification of ECM proteins. (c) F-actin-stained PC12 cells that show the difference of cell spreading and proliferation between ITO electrode and LHONA-generated ITO electrode.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 7. Fluorescence images of F-actin-stained PC12 cells on tissue culture plates (TCPs), bare gold and LHONA without modification of Matrigel which were used for the calculation of cell spreading and cell numbers remaining on the substrate after fixation.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 8. Optical images of PC12 cells grown on Bare Au, LHONA with or without Matrigel. Pictures were taken every day for 3 days of culture.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 9. (a) F-actin-stained images of PC12 cells showing (b) cell proliferation and (c) spreading on Matrigel-coated TCP, Bare gold and LHONA. Difference of cell morphology was disappeared due to the modification of Matrigel on each substrate that eliminated the effects of nanotopography on cell behaviors. (‘NS’ means that there are no statistical difference between each group (ANOVA test, N=3).

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 10. Cyclic voltammogram of different substrates with (a) DPBS, (b) PC12 without L-DOPA treatment and (c) PC12 with L-DOPA treatment. (d) Ipc values of DA calculated from (b) and (c).

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 11. Cyclic voltammogram of PC12 on LHONA-M without L-DOPA treatment with different cycles (a) 1st – 5th, (b) 6th – 9th and (c) 10th. Cyclic voltammogram of PC12 on LHONA-M with L-DOPA treatment with different cycles (d) 1st – 5th, (e) 6th – 9th and (f) 10th.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 12. Model dopaminergic cells (PC12) on the LHONA with different cell density to confirm cell density-dependent electrochemical signals of dopamine. Cyclic voltammetry was utilized to check the reduction (Ipc) and oxidation peaks (Ipa) with the scan rate of 50mV/s using DPBS (pH 7.4) as a electrolyte.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGSURE 13. Ampeometric detection of DA release from PC12 cells which was triggered by high concentration (120mM) of potassium chloride. Arrows indicate the time of adding KCl.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 14. Pseudocolored image of dopaminergic neurons derived from hNSCs (ReNcell VM) that were grown on the LHONA.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 15. The expression level of one of the representative marker of dopaminergic neurons, Nurr 1. (*non-paired student t-test.)

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 16. Phase contrast images of hNSCs, Neurospheres, Premature neurons and Neurons which were attached on the surface of LHONA for electrochemical analysis. Scale bar = 100μm

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 17. HPLC results obtained from i) the dopamine dissolved in the medium, ii) the medium collected from human neural stem cells (hNSCs) with L-DOPA pre-treatment, iii) the medium collected from dopaminergic cells derived from hNSCs without L-DOPA pre-treatment and iv) the medium collected from dopaminergic cells derived from hNSCs with L-DOPA pre-treatment.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 18. CV signals of dopaminergic neurons treated with DPBS for (a) 30min, (b) 60min, (c) 3days and (d) its corresponding cathodic peaks. Student’s t-test was used for evaluating significance (*p<0.01, N=3), compared to the cathodic current of cells treated with DPBS for 3 days.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 19. CV signals of other types of cells (Non-dopaminergic neurons, Astrocytes, Human dermal fibroblasts).

Acknowledgments

J.-W.C. acknowledges financial support from Leading Foreign Research Institute Recruitment Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (MSIP) (2013K1A4A3055268). K.-B.L. acknowledges financial support from the NIH R21 grant [1R21NS085569–01].

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Tae-Hyung Kim, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854 (USA)

Dr. Cheol-Heon Yea, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854 (USA). Department of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering, Sogang University, Seoul 121-742 (Republic of Korea)

Sy-Tsong Dean Chueng, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854 (USA).

Perry To-Tien Yin, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854 (USA).

Brian Conley, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854 (USA).

Kholud Dardir, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854 (USA).

Yusin Pak, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Gwangju, 500-712 (Republic of Korea).

Prof. Gun Young Jung, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Gwangju, 500-712 (Republic of Korea)

Prof. Jeong-Woo Choi, Email: jwchoi@sogang.ac.kr, Department of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering, Sogang University, Seoul 121-742 (Republic of Korea), Fax: (+82) 2-3273-0331

Prof. Ki-Bum Lee, Email: kblee@rutgers.edu, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854 (USA), Fax: (+1) 732-445-5312, http://kblee.rutgers.edu/. Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854 (USA)

References

- 1.a) Guvendiren M, Burdick JA. Nat Commun. 2012;3:792. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Weissman IL. Science. 2000;287:1442. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Maroof AM, Keros S, Tyson JA, Ying SW, Ganat YM, Merkle FT, Liu B, Goulburn A, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG, Widmer HR, Eggan K, Goldstein PA, Anderson SA, Studer L. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:559. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kim T-H, Shah S, Yang L, Yin PT, Hossain MK, Conley B, Choi J-W, Lee K-B. ACS Nano. 2015 doi: 10.1021/nn5066028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Guilak F, Cohen DM, Estes BT, Gimble JM, Liedtke W, Chen CS. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:17. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Cell. 2006;126:677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Castiglioni V, Onorati M, Rochon C, Cattaneo E. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:30. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Yin PT, Shah S, Chhowalla M, Lee K-B. Chem Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1021/cr500537t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Shah S, Yin PT, Uehara TM, Chueng STD, Yang LT, Lee KB. Adv Mater. 2014;26:3673. doi: 10.1002/adma.201400523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nikkhah M, Edalat F, Manoucheri S, Khademhosseini A. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5230. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Han DW, Tapia N, Hermann A, Hemmer K, Hoing S, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Zaehres H, Wu GM, Frank S, Moritz S, Greber B, Yang JH, Lee HT, Schwamborn JC, Storch A, Scholer HR. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:465. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Bellin M, Marchetto MC, Gage FH, Mummery CL. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:713. doi: 10.1038/nrm3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiang L, Fujita R, Abeliovich A. Neuron. 2013;78:957. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Wernig M, Zhao JP, Pruszak J, Hedlund E, Fu DD, Soldner F, Broccoli V, Constantine-Paton M, Isacson O, Jaenisch R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801677105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lindvall O, Kokaia Z, Martinez-Serrano A. Nat Med. 2004;10:S42. doi: 10.1038/nm1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kim JH, Auerbach JM, Rodriguez-Gomez JA, Velasco I, Gavin D, Lumelsky N, Lee SH, Nguyen J, Sanchez-Pernaute R, Bankiewicz K, McKay R. Nature. 2002;418:50. doi: 10.1038/nature00900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Biggs MJP, Richards RG, Gadegaard N, Wilkinson CDW, Oreffo ROC, Dalby MJ. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5094. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Milner KR, Siedlecki CA. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82:80. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) McMurray RJ, Gadegaard N, Tsimbouri PM, Burgess KV, McNamara LE, Tare R, Murawski K, Kingham E, Oreffo ROC, Dalby MJ. Nat Mater. 2011;10:637. doi: 10.1038/nmat3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kulangara K, Yang Y, Yang J, Leong KW. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4998. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Kim DH, Provenzano PP, Smith CL, Levchenko A. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:351. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Dalby MJ, Gadegaard N, Oreffo ROC. Nat Mater. 2014;13:558. doi: 10.1038/nmat3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Chen WQ, Villa-Diaz LG, Sun YB, Weng SN, Kim JK, Lam RHW, Han L, Fan R, Krebsbach PH, Fu JP. ACS Nano. 2012;6:4094. doi: 10.1021/nn3004923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Cui HF, Ye JS, Chen Y, Chong SC, Liu X, Lim TM, Sheu FS. Sens Actuator B-Chem. 2006;115:634. [Google Scholar]; b) Amato L, Heiskanen A, Caviglia C, Shah F, Zor K, Skolimowski M, Madou M, Gammelgaard L, Hansen R, Seiz EG, Ramos M, Moreno TR, Martinez-Serrano A, Keller SS, Emneus J. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:7042. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hariri MB, Dolati A, Moakhar RS. J Electrochem Soc. 2013;160:D279. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Zhou M, Zhai YM, Dong SJ. Anal Chem. 2009;81:5603. doi: 10.1021/ac900136z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tang LH, Wang Y, Li YM, Feng HB, Lu J, Li JH. Adv Funct Mater. 2009;19:2782. [Google Scholar]; c) Alwarappan S, Erdem A, Liu C, Li CZ. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:8853. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui HF, Ye JS, Chen Y, Chong SC, Sheu FS. Anal Chem. 2006;78:6347. doi: 10.1021/ac060018d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kafi MA, El-Said WA, Kim TH, Choi JW. Biomaterials. 2012;33:731. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petit GH, Olsson TT, Brundin P. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2014;40:60. doi: 10.1111/nan.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Pai S, Verrier F, Sun HY, Hu HB, Ferrie AM, Eshraghi A, Fang Y. J Biomol Screen. 2012;17:1180. doi: 10.1177/1087057112455059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Donato R, Miljan EA, Hines SJ, Aouabdi S, Pollock K, Patel S, Edwards FA, Sinden JD. BMC Neurosci. 2007:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chaudhry ZL, Ahmed BY. Neurol Res. 2013;35:435. doi: 10.1179/1743132812Y.0000000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caiazzo M, Dell’Anno MT, Dvoretskova E, Lazarevic D, Taverna S, Leo D, Sotnikova TD, Menegon A, Roncaglia P, Colciago G, Russo G, Carninci P, Pezzoli G, Gainetdinov RR, Gustincich S, Dityatev A, Broccoli V. Nature. 2011;476:224. doi: 10.1038/nature10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1. (a) Schematic diagram representing the set-up of laser interference lithography (LIL) to generate homogeneous photoresist nanostructures. (b) FE-SEM images of homogeneous nanoholes with size of (i) 150nm, (ii) 200nm, (iii) 500m, respectively, and nanolines with size of (iv) 200nm, (v) 300nm, respectively.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 2. (a) Schematic diagram representing two different deposition methods used in this study to fabricate large-scale homogeneous metal nanostructures. (b) SEM images of homogeneous nanostructures of gold nanodots with size of (i) 500nm and (ii) 350nm, respectively, and (iii) gold nanocups with size of 350nm. Structure (i) was fabricated by E-beam evaporation method while structure (ii) and (iii) were fabricated by electrochemical deposition method. Indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode was utilized as a supporting material for all substrates.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 3. (a) I-t curve used for the electrochemical deposition of gold through PR nanoholes with varying deposition time. (b) Voltammogram achieved from LHONA with different deposition time in the presence of 5μM DA. Arrows indicate that reduction (Epc) and oxidation peaks (Epa) are increasing with increase of the deposition time. (c) Current values obtained from (b) showing increase of peak currents at V (vs. Ag/AgCl) = 130mV. Student’s t-test was used for evaluating significance (*p<0.01, N=3), compared to the current values of 5μM DA achieved from LHONA with 120s deposition of gold.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 4. Voltammetric signals of dopamine achieved from (a) different types of substrates and (b) with different concentrations of dopamine (0.1 – 3 μM)

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 5. (a) Cyclic voltammeric curves with varying the scan rate and (b) its corresponding current values at reduction and oxidation potential showing linear correlations between scan rate and electrochemical signals. (c) Voltammogram achieved from LHONA (240s deposition) with varying DA concentrations from 0 to 50 μM and (d) linear correlations between the concentrations of DA and currents values at Epc.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 6. Fluorescence images of F-actin-stained PC12 cells on (a) Bare gold and (b) LHONA substrates without modification of ECM proteins. (c) F-actin-stained PC12 cells that show the difference of cell spreading and proliferation between ITO electrode and LHONA-generated ITO electrode.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 7. Fluorescence images of F-actin-stained PC12 cells on tissue culture plates (TCPs), bare gold and LHONA without modification of Matrigel which were used for the calculation of cell spreading and cell numbers remaining on the substrate after fixation.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 8. Optical images of PC12 cells grown on Bare Au, LHONA with or without Matrigel. Pictures were taken every day for 3 days of culture.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 9. (a) F-actin-stained images of PC12 cells showing (b) cell proliferation and (c) spreading on Matrigel-coated TCP, Bare gold and LHONA. Difference of cell morphology was disappeared due to the modification of Matrigel on each substrate that eliminated the effects of nanotopography on cell behaviors. (‘NS’ means that there are no statistical difference between each group (ANOVA test, N=3).

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 10. Cyclic voltammogram of different substrates with (a) DPBS, (b) PC12 without L-DOPA treatment and (c) PC12 with L-DOPA treatment. (d) Ipc values of DA calculated from (b) and (c).

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 11. Cyclic voltammogram of PC12 on LHONA-M without L-DOPA treatment with different cycles (a) 1st – 5th, (b) 6th – 9th and (c) 10th. Cyclic voltammogram of PC12 on LHONA-M with L-DOPA treatment with different cycles (d) 1st – 5th, (e) 6th – 9th and (f) 10th.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 12. Model dopaminergic cells (PC12) on the LHONA with different cell density to confirm cell density-dependent electrochemical signals of dopamine. Cyclic voltammetry was utilized to check the reduction (Ipc) and oxidation peaks (Ipa) with the scan rate of 50mV/s using DPBS (pH 7.4) as a electrolyte.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGSURE 13. Ampeometric detection of DA release from PC12 cells which was triggered by high concentration (120mM) of potassium chloride. Arrows indicate the time of adding KCl.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 14. Pseudocolored image of dopaminergic neurons derived from hNSCs (ReNcell VM) that were grown on the LHONA.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 15. The expression level of one of the representative marker of dopaminergic neurons, Nurr 1. (*non-paired student t-test.)

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 16. Phase contrast images of hNSCs, Neurospheres, Premature neurons and Neurons which were attached on the surface of LHONA for electrochemical analysis. Scale bar = 100μm

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 17. HPLC results obtained from i) the dopamine dissolved in the medium, ii) the medium collected from human neural stem cells (hNSCs) with L-DOPA pre-treatment, iii) the medium collected from dopaminergic cells derived from hNSCs without L-DOPA pre-treatment and iv) the medium collected from dopaminergic cells derived from hNSCs with L-DOPA pre-treatment.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 18. CV signals of dopaminergic neurons treated with DPBS for (a) 30min, (b) 60min, (c) 3days and (d) its corresponding cathodic peaks. Student’s t-test was used for evaluating significance (*p<0.01, N=3), compared to the cathodic current of cells treated with DPBS for 3 days.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 19. CV signals of other types of cells (Non-dopaminergic neurons, Astrocytes, Human dermal fibroblasts).