Abstract

We report here the comparison of five classes of unnatural amino acid building blocks for their ability to be accommodated into an α-helix in a protein tertiary fold context. High-resolution structural characterization and analysis of folding thermodynamics yield new insights into the relationship between backbone composition and folding energetics in α-helix mimetics and suggest refined design rules for engineering the backbones of natural sequences.

Foldamers,1 unnatural oligomers capable of adopting discrete folded structures reminiscent of those seen in nature, have found utility in a variety of applications.2 In a body of research spanning more than 20 years, a wealth of secondary structures, including helices, turns, and sheets, have been shown to be accessible by backbones of diverse chemical compositions. A frontier challenge in the field is determining how to combine these secondary structures into more complex tertiary and quaternary folding topologies, either biologically inspired3 or abiotic in design.4 The significance of this as an objective stems from the prospect of expanding the range of functions accessible when diverse natural folding patterns are achievable by such agents.

While many foldamer structures have been developed through de novo design, backbone engineering of biological sequences has been shown as a viable strategy for recreating a variety of natural folds and functions.5 In this approach, a portion of the α-amino acid residues in a designated mimetic target are replaced by analogues with an altered backbone, and modifications are made in a way that retains as many of the original side-chain functional groups as possible. The result is a “heterogeneous-backbone” oligomer consisting of a mixture of α-residues and unnatural counterparts that collectively display a native-like sequence of side chains (e.g., an α/β-peptide that blends α- and β-amino acid residues6). If modifications are made carefully, such analogues can show similar folding behaviour and biological function as the prototype natural sequence but improved stability to enzymatic degradation in vitro7 and in vivo.8

Sequence-guided backbone engineering has found wide use in mimicry of helix6a,8 and sheet3a,9,10 secondary structures. We recently showed that this modification strategy is also capable of generating more complex tertiary folding patterns.11 This goal was realized through the simultaneous modification of helix, loop, sheet, and turn secondary structures in a small bacterial protein with several unnatural residue classes. Examination of the effect of individual modifications revealed that changes to the α-helix were the most detrimental to tertiary fold stability. The prevalence of α-helices in proteins makes this an important limitation and reversing the destabilization resulting from helix backbone modification an important goal if backbone engineering is to prove a general method for developing foldamer analogues of a wider array of target tertiary folds.

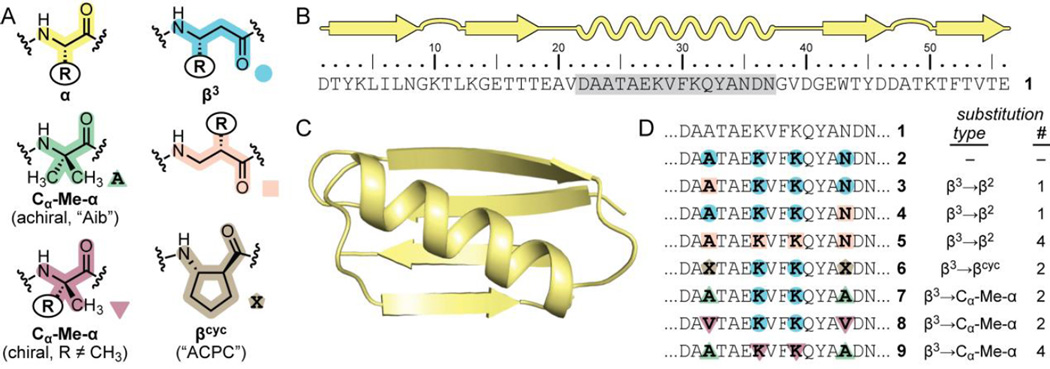

Here, we compare five classes of unnatural-backbone units (Fig. 1A) for the ability to be accommodated into α-helical secondary structure in a protein context: β3-residues, β2-residues, the βcyc-residue ACPC, the achiral Cα-Me-α-residue Aib, and chiral Cα-Me-α-residues (Fig. 1A). While each of these classes is known, no prior effort has compared them side-by-side for the ability to stabilize helical folds in a heterogeneous backbone. High-resolution structural characterization and biophysical analysis of folding thermodynamics in a series of variants of a common protein scaffold provide a robust picture of the relationship between backbone composition and folding propensity of α-helix mimetic foldamers.

Fig. 1.

(A) Structures of a natural α-residue and five classes of unnatural replacements compared herein. (B, C) Sequence and crystal structure (PDB 2QMT) of Streptococcal protein GB1 (1), the host sequence for helix modification; the crystal structure differs from the wild-type sequence at the N-terminus (MQ in crystal structure vs. DT in 1). (D) Sequences for variants of protein 1 bearing heterogeneous-backbone helices; note, 1–9 are all 56-residue oligomers, but only the helical segment (gray shading in A) is shown. For β3, β2, and chiral Cα-Me-α-residues, the R group in the building block is that of the corresponding natural α-amino acid denoted by the single letter code in the sequence.

The host sequence in the present work is protein GB1 (1, Fig. 1B,C), and our first-generation design for helix modification, previously reported,11 makes use of β3-residues in an α→β3 substitution scheme that conserves the parent side chain at each site (2, Fig. 1D). Making one substitution in each turn of the GB1 helix resulted in an identical folded structure but destabilized the folded state considerably.12 Protein 2 will serve as the benchmark for comparison of strategies for helix backbone modification examined herein.

The first variable we investigated in the relationship between backbone composition and helix stability was the placement of β-residue side chains. β3-residues, in which the side chain is attached adjacent to the amide nitrogen, are common foldamer building blocks due to their commercial availability. The regioisomeric β2-residues, where the side chain is adjacent to the carbonyl, are less utilized; however, they have been studied in contexts including pure β-peptide helices13 and mixed-backbone α/β-peptide sheets.10a,10b We were motivated to examine β3→β2 substitution in the helix of GB1 by two factors. First, results from a prior computational study suggest β2-residues may be more predisposed than β3 counterparts to support the backbone conformation adopted in heterogeneous-backbone α/β-peptide helices.14 Second, the side chain movement from β3→β2 substitution restores a local orbital interaction involving an Asn side chain that may be important to folded stability (vide infra).

We designed proteins 3–5 (Fig. 1D) to ascertain the effect of β-residue side-chain placement on folded stability of helix-modified GB1 variants. Derivatives of β2-Ala and β2-Lys suitable for use in solid-phase synthesis were prepared by reported routes,15 and a new protected form of β2-Asn was prepared by adaptation of known methods (Scheme S1).16 We synthesized proteins 3–5 by standard Fmoc solid phase methods and purified each by HPLC and ion exchange chromatography (Fig. S1, Table S1). Proteins were assayed by coupled thermal and chemical denaturation monitored by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to probe folding thermodynamics (Fig. S4).12,17 Each protein was also subjected to crystallization trials by hanging drop vapour diffusion, leading to single crystals of 3 and 4 that were analysed by X-ray diffraction and solved to 1.95 Å and 1.80 Å, respectively (Table S2).

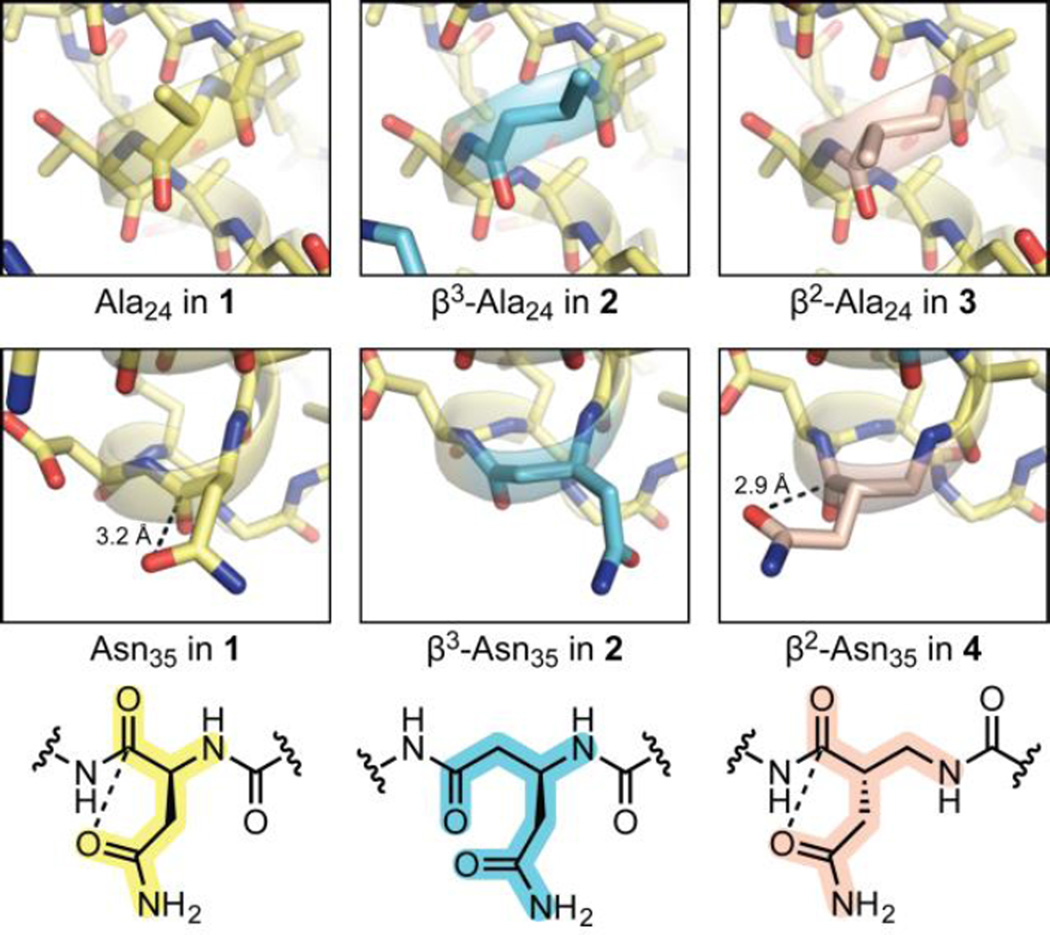

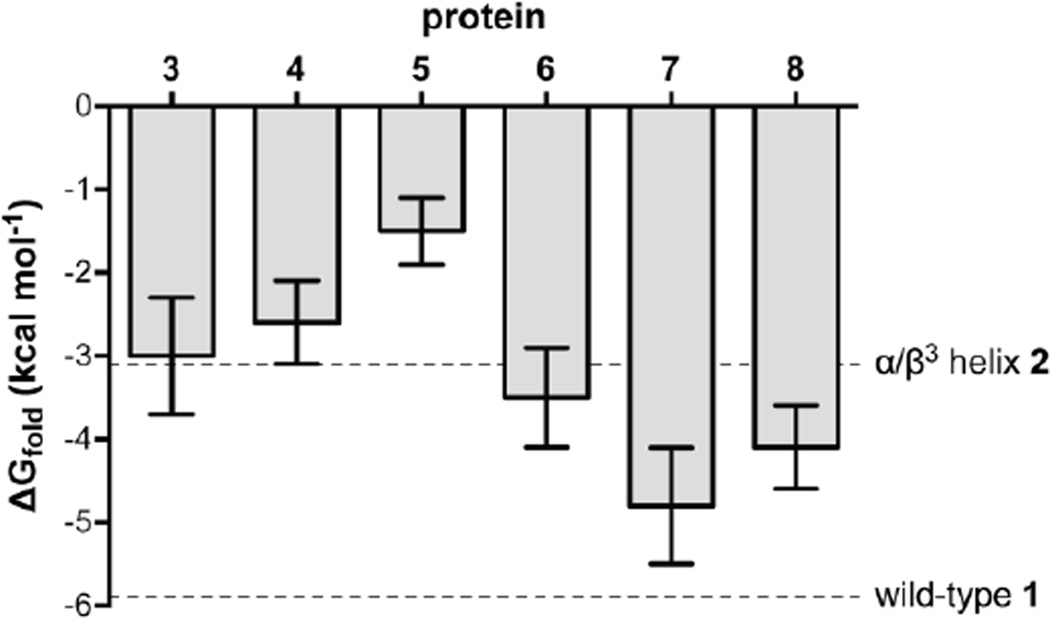

Aside from the expected side-chain displacements, analogues 3 and 4 exhibit essentially identical tertiary folds as both natural backbone 1 and analogue 2 bearing an α/β3 helix (Fig. 2). Analysis of folding thermodynamics revealed individual β3→β2 replacement was neutral to slightly destabilizing (Fig. 3), although magnitudes of the differences were small and similar within experimental uncertainty. The unfavourable effect on folding free energy is made up of an enthalpic stabilization that is more than overcome by an entropic penalty (Table S3). Though the exact origin of the entropy enthalpy compensation is not clear, changes in the sensitivity of the folded state to chemical denaturant and the heat capacity difference between the folded and unfolded states (Table S3) suggest a more compact denatured ensemble in β2-residue containing variants vs. β3 counterparts.12

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the corresponding α-, β3-, and β2-residues at two sites in the crystal structures of 1–4 (PDB 2QMT, 4KGR, 5HFY, and 5HG2). For position Asn35, chemical structures and distances for putative side-chain to backbone n→π* interactions are shown. In the structure for 1, the side chain carboxamide of Asn35 is flipped relative to the reported structure (PDB 2QMT).

Fig. 3.

Folding free energy at 298 K for proteins 1–8. Error bars show parameter uncertainty from the fits (Fig S4, Table S3).

Recent published findings highlight the importance of local orbital interactions in protein folding energetics.18 One example is an intramolecular n→π* overlap in Asn involving partial donation of a carboxamide lone pair into an antibonding orbital from the backbone carbonyl.19 Based on the observed distance from side-chain C=O to backbone C=O,19 evidence for this interaction is seen at α-Asn35 in wild-type 1 (PDB 2QMT20) and β2-Asn35 in 4 (two of four chains in the asymmetric unit); however, the β3-residue connectivity does not allow the necessary side-chain orientation at β3-Asn35 in 2 (Fig. 2). The n→π* interaction has been suggested to be worth up to 1.2 kcal mol−1 in folding enthalpy.19 An enthalpic stabilization of 0.4 kcal mol−1 was observed upon β3→β2-Asn substitution in 4 vs. 2; however, the change was comparable to that from β3→β2-Ala replacement in 3 vs. 2, where no functional side chain was involved. Collectively, the above data support the hypothesis that β2 residues are superior to β3 analogues in their ability to recapitulate side-chain to backbone orbital interactions; however, this difference does not appear to contribute significantly to folding energetics in this specific system.

Global β3→β2 residue replacement in 2 to produce analogue 5 was significantly destabilizing, and the energetic penalty was almost entirely enthalpic in origin. This result was somewhat surprising given the enthalpic stabilization observed in variants 3 and 4. Based on the data obtained for 2–4, part of the ~1.6 kcal mol−1 difference in folding free energy between 2 and 5 can be attributed to the substitution of β3→β2-Ala (0.1 kcal mol−1) and β3→β2-Asn (0.5 kcal mol−1). The remaining 1.0 kcal mol−1 penalty comes from the β3→β2-Lys replacements, and we suspect the dominant contribution arises from altered interactions involving Lys31, as detailed below.

In wild-type protein 1, Lys31 forms van der Waals contacts with Trp43 in the hydrophobic core and a salt bridge with Glu27. In variants 2–4, the same tertiary contacts are observed (Fig. S5). Crystallization attempts with 5 were not fruitful; however, movement of the side chain at Lys31 after β3→β2 substitution should abolish these tertiary contacts (Fig. S5) and destabilize the fold. Supporting this hypothesis, removal of the side chain in question by Lys31→Ala mutation on the natural backbone results in a comparable degree of destabilization of 0.9 kcal mol−1 (Fig. S6, Table S3) as calculated for the remaining difference for 5 vs. 2 (vide supra).

From a design standpoint, the above results suggest that β3- and β2-residues are comparable in terms of fundamental folding propensity as components of heterogeneous-backbone α/β-peptide helices. Selection of the optimal regioisomer is context dependent and must take into account side-chain contacts important to folding and/or function. While the above examples show how β3→β2 substitution can be detrimental, it stands to reason that an identical adjustment of side-chain placement could be beneficial in other systems. Thus, while the commercial availability of protected β3 building blocks make them a good choice for backbone modification, the more synthetically challenging β2 analogues are likely to be valuable in certain cases.

In situations where side chains make no important contacts related to folding or function, incorporation of βcyc-residues like ACPC in place of acylic β3-residues can improve helix folded stability.21 Protein 6 is a previously reported variant of 2 in which rigidified βcyc residues replace two β3-residues.12 In the GB1 tertiary fold, β3→βcyc substitution was structurally well accommodated but led to only a modest increase in folded stability. βcyc-Residues limit energetically accessible backbone conformational space by incorporating an otherwise freely rotatable bond into a ring. Thus, cyclization of β-residues can be thought of in similar terms as another known strategy for helix stabilization: methylation of Cα in α-residues. Cα-Me-α-residues are strong helix promoters,22 and the achiral variant Aib has previously been examined in protein contexts.23 The achiral nature of Aib leads to no inherent preference for a left- vs. right-handed helix; however, the biological arrangement can be favoured with chiral Cα-Me-α-residues.24

The above precedents led us to investigate which is a superior means of stabilizing a helical fold through backbone rigidification: chiral Cα-Me-α-, achiral Cα-Me-α-, or βcyc-residues. In order to probe this question experimentally, we prepared and characterized proteins 7–8, following the methods described above (Fig. S2, Table S1). Protein 7 is a variant of 6 in which the two outer β3-residues in the helix are replaced by Aib. In protein 8, these two sites incorporate the chiral Cα-methylated analogue of Val. Collectively, the series 6–8 enable the quantification of the relative benefit to folded stability from helix rigidification by the βcyc-residue ACPC, the achiral Cα-Me-α-residue Aib, and the chiral Cα-Me-α analogue of Val.

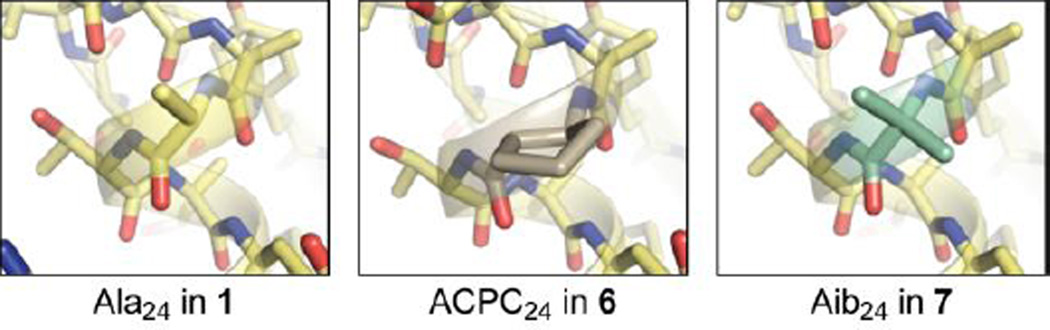

A crystal structure of 7 solved to 2.15 Å resolution showed that, as expected, Cα-Me-α-residues are well accommodated in a helix that also contains β3-residues (Fig. 4). β3→Aib replacement stabilized the folded state considerably (Fig. 3), enhancing folding free energy by 1.7 kcal mol−1 in 7 vs. 2. The stabilization was entirely enthalpic and partially offset by a surprisingly large unfavourable impact on folding entropy. Replacement of the Aib residues in 7 with the chiral Cα-Me-Val reduced the entropic penalty, suggesting it may be tied to the accessibility of left-handed helical dihedrals in the former leading to a greater number of conformational states in the unfolded ensemble. Unexpectedly, Aib→Cα-Me-Val replacement was also accompanied by an unfavourable impact on folding enthalpy, the origin of which is not clear. The net effect was a diminished overall folding free energy from β3→Cα-Me-Val vs. β3→Aib substitution. The improved enthalphic stability of both Cα-Me-α variants 7–8 over all β-residue variants 2–6 suggests a more native-like helix geometry as an explanation for the improved folding stability. Comparing the folding free energy among 6–8 suggests that the relative ability to stabilize a helical fold in a protein context follows the trend Aib > Cα-Me-Val > ACPC.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the corresponding α-, βcyc-, and Cα-Me-α-residues at position 24 in the crystal structures of 1, 6, and 7 (PDB 2QMT, 4OZB, and 5HI1).

Encouraged by the results for proteins 7 and 8, we next replaced all four sites in the helix with Cα-Me-α-residues. Ala24 and Asn35 were replaced with Aib, while Lys28 and Lys31 were replaced with Cα-Me-Lys to produce GB1 analogue 9 (Fig. 1D). The synthesis and purification of 9 proved challenging, and the yield of purified material insufficient for full analysis of folding thermodynamics. A simple CD melt, however, showed 9 to be the most thermally stable among the mutants examined here (Fig. S7); its melting temperature (Tm) was only 2.5 °C lower than all-natural backbone 1. The slightly lower Tm of 9 relative to 1 may result from a steric clash of the Lys31 Cα-Me group with Trp43. Overall, these results further confirm chiral Cα-Me-α-residues are superior to β-residues (β3, β2, or βcyc) as components of mixed-backbone helices; however, the synthetic challenge in their preparation and incorporation by solid-phase synthesis mitigates this utility somewhat.

In summary, we have reported here the comparative effect on folded structure and thermodynamics of five residue types as components of heterogeneous-backbone helix mimetics in a tertiary fold context. No significant difference was seen in helix folding propensity between β3 vs. β2 residues; however, the choice between them is important when a particular side chain is involved in tertiary contacts. In cases where side-chain functional groups are not critical, the Cα-Me-α-residue Aib was superior to Cα-Me-α-Val and the βcyc-residue ACPC as a helix rigidifier. In all cases, Cα-Me-α-residues (chiral or achiral) proved better than β-residues in helix stabilization. The refined design rules reported here for α-helix modification, taken with recent efforts involving β-sheets, represent a significant advance toward the application of backbone engineering to the design of protein mimetics with both native-like tertiary folded structure and thermodynamic stability. The results are also interesting to consider in relation to the diversity of non-canonical amino acids isolated from meteorites and experiments that mimic prebiotic environments.25

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM107161 to W.S.H.). We thank Timothy Cunningham and Sunil Saxena for plasmids used in the expression of wild-type GB1 and the K31A mutant.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Figures S1–S7, Tables S1–S3, Scheme S1, and methods. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Gellman SH. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Bautista AD, Craig CJ, Harker EA, Schepartz A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goodman CM, Choi S, Shandler S, DeGrado WF. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nchembio876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guichard G, Huc I. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:5933–5941. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Horne WS. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2011;6:1247–1262. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.632002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Martinek TA, Fulop F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:687–702. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15097a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Sun J, Zuckermann RN. ACS Nano. 2013;7:4715–4732. doi: 10.1021/nn4015714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Hegedüs Z, Wéber E, Kriston-Pál É, Makra I, Czibula Á, Monostori É, Martinek TA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16578–16584. doi: 10.1021/ja408054f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang PSP, Nguyen JB, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:6810–6813. doi: 10.1021/ja5013849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Checco JW, Kreitler DF, Thomas NC, Belair DG, Rettko NJ, Murphy WL, Forest KT, Gellman SH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:4552–4557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420380112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Mannige RV, Haxton TK, Proulx C, Robertson EJ, Battigelli A, Butterfoss GL, Zuckermann RN, Whitelam S. Nature. 2015;526:415–420. doi: 10.1038/nature15363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chandramouli N, Ferrand Y, Lautrette G, Kauffmann B, Mackereth CD, Laguerre M, Dubreuil D, Huc I. Nature Chem. 2015;7:334–341. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Collie GW, Pulka-Ziach K, Lombardo CM, Fremaux J, Rosu F, Decossas M, Mauran L, Lambert O, Gabelica V, Mackereth CD, Guichard G. Nature Chem. 2015;7:871–878. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinert ZE, Horne WS. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:8796–8802. doi: 10.1039/c4ob01769b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Johnson LM, Gellman SH. Methods Enzymol. 2013;523:407–429. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394292-0.00019-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Werner HM, Horne WS. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015;28:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner HM, Cabalteja CC, Horne WS. Chem Bio Chem. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheloha RW, Maeda A, Dean T, Gardella TJ, Gellman SH. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:653–655. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pham JD, Spencer RK, Chen KH, Nowick JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12682–12690. doi: 10.1021/ja505713y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Lengyel GA, Frank RC, Horne WS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4246–4249. doi: 10.1021/ja2002346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lengyel GA, Horne WS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:15906–15913. doi: 10.1021/ja306311r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lengyel GA, Eddinger GA, Horne WS. Org. Lett. 2013;15:944–947. doi: 10.1021/ol4001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lengyel GA, Reinert ZE, Griffith BD, Horne WS. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:5375–5381. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00886c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reinert ZE, Lengyel GA, Horne WS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12528–12531. doi: 10.1021/ja405422v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinert ZE, Horne WS. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:3325–3330. doi: 10.1039/C4SC01094A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seebach D, Abele S, Gademann K, Guichard G, Hintermann T, Jaun B, Matthews JL, Schreiber JV, Oberer L, Hommel U, Widmer H. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1998;81:932–982. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Möhle K, Günther R, Thormann M, Sewald N, Hofmann H-J. Biopolymers. 1999;50:167–184. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199908)50:2<167::AID-BIP6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi Y, English EP, Pomerantz WC, Horne WS, Joyce LA, Alexander LR, Fleming WS, Hopkins EA, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6050–6055. doi: 10.1021/ja070063i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Carpino LA, Chao HG, Ghassemi S, Mansour EME, Riemer C, Warrass R, Sadat-Aalaee D, Truran GA, Imazumi H, Wenschuh H, Beyermann M, Bienert M, Shroff H, Albericio F, Triolo SA, Sole NA, Kates SA. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:7718–7719. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mazzini C, Lebreton J, Alphand V, Furstoss R. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:5215–5218. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ok T, Jeon A, Lee J, Lim JH, Hong CS, Lee H-S. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:7390–7393. doi: 10.1021/jo0709605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhlman B, Raleigh DP. Protein Sci. 1998;7:2405–2412. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560071118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartlett GJ, Choudhary A, Raines RT, Woolfson DN. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:615–620. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartlett GJ, Newberry RW, VanVeller B, Raines RT, Woolfson DN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:18682–18688. doi: 10.1021/ja4106122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frericks Schmidt HL, Sperling LJ, Gao YG, Wylie BJ, Boettcher JM, Wilson SR, Rienstra CM. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:14362–14369. doi: 10.1021/jp075531p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horne WS, Price JL, Gellman SH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9151–9156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Karle IL, Balaram P. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6747–6756. doi: 10.1021/bi00481a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Marshall GR, Hodgkin EE, Langs DA, Smith GD, Zabrocki J, Leplawy MT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:487–491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) O'Neil KT, DeGrado WF. Science. 1990;250:646–651. doi: 10.1126/science.2237415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) De Filippis V, De Antoni F, Frigo M, Polverino de Laureto P, Fontana A. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1686–1696. doi: 10.1021/bi971937o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Torbeev VY, Raghuraman H, Hamelberg D, Tonelli M, Westler WM, Perozo E, Kent SBH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:20982–20987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111202108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crisma M, Toniolo C. Pept. Sci. 2015;104:46–64. doi: 10.1002/bip.22581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Burton AS, Stern JC, Elsila JE, Glavin DP, Dworkin JP. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:5459–5472. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35109a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bada JL. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:2186–2196. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35433d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.