Abstract

Purpose

To identify and describe homogenous classes of male college students based on their weight-related behaviors (e.g., eating habits, physical activity, and unhealthy weight control) and to examine differences by sexual orientation.

Design

Study design was a cross-sectional sample of 2- and 4-year college students.

Setting

Study setting was forty-six 2- and 4-year colleges in Minnesota.

Subjects

Study subjects comprised 10,406 college males.

Measures

Measures were five categories of sexual orientation derived from self-reported sexual identity and behavior (heterosexual, discordant heterosexual [identifies as heterosexual and engages in same-sex sexual behavior], gay, bisexual, and unsure) and nine weight-related behaviors (including measures for eating habits, physical activity, and unhealthy weight control).

Analysis

Latent class models were fit for each of the five sexual orientation groups, using the nine weight-related behaviors.

Results

Overall, four classes were identified: “healthier eating habits” (prevalence range, 39.4%–77.3%), “moderate eating habits” (12.0%–30.2%), “unhealthy weight control” (2.6%–30.4%), and “healthier eating habits, more physically active” (35.8%). Heterosexual males exhibited all four patterns, gay and unsure males exhibited four patterns that included variations on the overall classes identified, discordant heterosexual males exhibited two patterns (“healthier eating habits” and “unhealthy weight control”), and bisexual males exhibited three patterns (“healthier eating habits,” “moderate eating habits,” and “unhealthy weight control”).

Conclusion

Findings highlight the need for multibehavioral interventions for discordant heterosexual, gay, bisexual, and unsure college males, particularly around encouraging physical activity and reducing unhealthy weight control behaviors.

Keywords: Sexual Orientation Disparities, College Males, Young Adults, Physical Activity, Unhealthy Weight Control, Dietary Intake, Prevention Research

INTRODUCTION

Background

A recent Institute of Medicine report on lesbian, gay, and bisexual health highlighted several limitations of existing weight-related research for these sexual orientation groups, particularly among men.1 Existing evidence suggests that gay and bisexual adult men may be at lower risk of obesity and higher risk of disordered eating than heterosexual men.2–17 Other research suggests that there may not be differences in the frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption between gay, bisexual, and heterosexual men,3,18 but research on disparities in other aspects of nutrition and eating patterns by sexual orientation is lacking. There is slightly more research on physical activity, and findings are generally mixed, in part because of differences in measurement of physical activity. Some evidence suggests lower levels of physical activity among gay or bisexual men compared with straight men,3,19,20 whereas one other study found more physical activity, particularly strengthening physical activity, among gay or bisexual men.18

A substantial proportion of college students are overweight or obese. For example, findings from the 2007–2008 College Student Health Survey, including self-reported data from more than 16,000 college students at 27 postsecondary campuses in Minnesota, indicated that 45% of college students have a body mass index (BMI) classified as overweight or obese, with particularly high rates among male students (52%).21 Estimates of over-weight and obesity from the College Student Health Survey are similar to national estimates from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System for young adults ages 18 to 24 years, based on self-reported data (41.7%).22 Further, our previous work on weight-related disparities among college males found that compared with heterosexual college men, bisexual men were significantly more likely to have a BMI ≥35 kg/m2, whereas gay men were significantly less likely to have a BMI ≥25 kg/m2.16 Interestingly, gay college males were at particularly high risk for poor weight-related behaviors, including frequent eating away from home, insufficient physical activity, unhealthy weight control behaviors, and binge eating. Moreover, compared with heterosexual college males, gay, bisexual, and unsure males were less likely to engage in sufficient strenuous physical activity.16 These findings underscore the importance of sexual orientation disparities during the college years, which is also a time when engagement in healthful weight-related behaviors tends to decline23–33 and when many people explore aspects related to sexuality.34–37 Additionally, nearly half of adults ages 18 to 24 years attend college, representing a critical mass of this age group and accessible population in which to design and deliver weight-related behavioral interventions that address sexual orientation–related health disparities.38

In exploring sexual orientation disparities for weight-related health, there are some important considerations. First, it is important to examine males and females separately because existing evidence suggests differences in weight-related health across both sexual orientation and gender. For example, although gay men are less likely to be overweight or obese than heterosexual men, gay or lesbian women are more likely to obese than heterosexual women.2–5,39,40 An area of weight-related health that is of particular concern among gay and bisexual men is related to disordered eating. Although findings for women have been mixed with regard to disordered eating (potentially due in part to differences in sampling),8,41 evidence suggests more disordered eating among gay men than heterosexual men.7–15,17,42–44 Second, it is also important to examine sexual orientation groups separately, rather than treating these groups as homogenous. For example, although gay men are less likely to be obese compared with heterosexual men, the evidence is not as consistent for bisexual men. Combining gay and bisexual men into a single group could attenuate effects for obesity. Finally, existing evidence has explored disparities across sexual orientation for specific behaviors (e.g., fruit and vegetable consumption and strengthening physical activity). Across gender and sexual orientation, how these behaviors co-occur with each other may differ, given known differences between men and women in weight-related health across sexual orientation. Because multiple weight-related behaviors contribute to one’s overall weight, being able to identify relevant subgroups with similar weight-related behaviors allows for intervention tailoring.

Purpose

The purpose of this study, therefore, was to identify and describe homogenous classes of male college students based on their weight-related behaviors (e.g., eating habits, physical activity, unhealthy weight control behaviors), and to examine differences across five sexual orientation groups. We hypothesized that there are distinct classes of weight-related behaviors that share common patterns across sexual orientation groups. In addition, we hypothesized that differences in the proportion of individuals in specific classes of weight-related behaviors exist across sexual orientation groups, with greater proportions of gay or bisexual men in unhealthy classes and exhibiting unhealthy patterns compared with heterosexual men.

METHODS

Design and Sample

Data were from the 2009–2013 College Student Health Survey (CSHS), an ongoing statewide surveillance system of 2- and 4-year colleges and universities across Minnesota. Between 2009 and 2013, 46 institutions participated in CSHS (26 were 2-year institutions and 20 were 4-year institutions). For most schools participating in the CSHS, students were randomly selected through a registrar’s enrollment list furnished by participating educational institutions. For smaller schools, all students were invited to participate in order to have sufficient sample sizes for reports generated for each school, whereas at larger schools only a proportion of students were invited (total sampling range, 12.5%–100%, dependent on school size). Eligible participants were sent multiple invitations, including postcards and e-mails, to anonymously complete an online survey. Participants who completed the survey were entered into a raffle to win prizes such as iPods, iPads, and gift cards. The overall response rate was 33.2%. Additional details, including surveys and reports, are available on-line (http://www.bhs.umn.edu/surveys/index.htm) and in our previously published works.16,21

A total of 30 of the 46 colleges participated in the CSHS in more than 1 year between 2009 and 2013. In order to minimize the possibility that participants were included in the data set more than once and to maximize sample size, a college’s second year of data was included only when the possibility of overlap in participants was expected to be negligible (i.e., less than 2%, calculated from percent of student body sampled, and graduation and retention rates), as has been done previously.16,45,46 Six schools had a negligible estimated percentage of overlap in the first and second samples (range, 0.45%–1.57%). Thus, an additional year of data was included for these schools (nstudents = 6912). This yielded a final merged 2009–2013 CSHS data set consisting of 29,118 students (nmales= 10,423).

Measures

Sexual orientation was assessed by self-report for both identity and behavior on the CSHS. Consistent with previous research using the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS)46 and CSHS16 data, we created the following categories for sexual orientation: “heterosexual” (identified as heterosexual and did not report engaging in any same-sex sexual behavior in the past year), “discordant heterosexual” (identified as heterosexual and reported engaging in same-sex sexual behavior in the past year), “gay/lesbian” (identified as gay or lesbian, regardless of sexual behavior), “bisexual” (identified as bisexual, regardless of sexual behavior), and “unsure” (identified as unsure about their sexual orientation, regardless of sexual behavior).

Behavioral measures covered four areas of weight-related behaviors: eating habits, physical activity, screen time, and unhealthy weight control behaviors. All variables were dichotomized based on existing public health recommendations, which have practical significance in that they serve as a meaningful threshold for health. Dichotomization also facilitated interpretation of results and accounted for the nonnormality of data. Additionally, these behaviors had a low but statistically significant correlation with BMI in this sample of male college students (R range, −.03 to −.14; p < .001 for all described behaviors except regular soda consumption, which had no significant correlation).

Aspects of eating habits assessed included fruit and vegetable, soda, diet soda, breakfast, fast food, and restaurant food consumption, which have been linked with weight status and other important health outcomes as well as having been highlighted as key health behaviors in leading recommendations for health, such as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.47–52 These items were assessed using standard questions adapted from the YRBS.53 Frequency response options ranged from, “I did not eat or drink this,” to “4 or more times per day.” Participants met recommendations if they reported consuming fruits and vegetables ≥5 times per day. For soda and diet soda, responses were dichotomized for each item as consuming <1 per day or >1 per day.21,54 Participants reported the number of days that they ate breakfast using the question, “how many days per week did you eat breakfast?”55 Breakfast consumption was dichotomized as ≥5 d/wk or <5 d/wk. The frequency of eating (1) fast food meals and (2) at non–fast food restaurants was also assessed. Response options ranged from “never” to “several times per day.” Consistent with previous literature, both fast food and restaurant food consumption were dichotomized as ≥several times per week vs. <several times per week.45,56,57

Three types of physical activity were assessed: strenuous, moderate, and strengthening. Examples were provided for each type of activity. Response options ranged from “None” to “6½+ hours.” Moderate and strenuous physical activities were combined into a single “moderate-to-vigorous physical activity” indicator. Meeting recommendations was ≥5 h/wk of moderate and vigorous physical activity combined or ≥4.5 h/wk of either moderate or vigorous physical activity (guided by recommendations for weight maintenance, which include ≥1 hour on most days of the week).58 Consistent with previous research using CSHS data, strengthening physical activity was categorized as ≥2.5 h/wk or ≤2 h/wk.59

Time spent watching television or using a computer (for things besides school or work) on an average day was used to assess screen time. Response options ranged from, “None” to “5+ hours.” Categories of ≥14 h/wk vs. <14 h/wk were created for screen time, in line with recommendations for young people of <2 h/d.60

Using a standard assessment of unhealthy weight control behaviors, participants indicated the frequency of four behaviors in the past 12 months: using laxatives to control weight, taking diet pills, binge eating, and inducing vomiting to control weight.21,55,61,62 This is similar to items that have been used extensively in other research, most notably the YRBS.17,43,63 Using laxatives, taking diet pills, and inducing vomiting were combined into a single unhealthy weight control behaviors variable (any vs. none), whereas binge eating, which is conceptually different from the other behaviors, was examined separately.16

Analysis

Latent class analysis (LCA) is a technique designed to identify a small number of homogenous subgroups within a larger heterogeneous group, based on responses to select indicators.64,65 LCA models with classes ranging from one to eight were fit, and the final model was selected using several available tools that aid in model selection including multiple fit criteria, such as information criteria (Akaike information criteria [AIC]; Bayesian information criteria [BIC]; adjusted BIC), and likelihood ratio tests (bootstrap likelihood ratio test [BLRT]). Solution interpretability, distribution of classes, and classification quality (e.g., entropy and class separation) are also used in model selection.64,66

After assessing initial LCA models, fruit and vegetable consumption and sedentary behavior were dropped as indicators because of similarities in responses across classes, thus not helping to differentiate classes. Nine indicators were included in final LCA models: soda, diet soda, fast food, restaurant food, and breakfast consumption; moderate-to-vigorous and strengthening physical activity; unhealthy weight control behaviors; and binge eating.

We fit LCA models to the whole sample of males and identified a best-fitting solution. To test for measurement invariance with regard to sexual orientation, the LCA solution was regressed on sexual orientation. Results were significant (p < .001), indicating differences across sexual orientation in the latent classes and that models should be stratified by sexual orientation. Upon examination of the final latent classes for each sexual orientation group, we determined that a multigroup LCA (allowing us to quantitatively examine differences between sexual orientation groups) would not be an appropriate strategy given the differing number of final classes. The final LCA models were selected based on fit and interpretability, with independent models for each sexual orientation group. Comparisons across sexual orientation groups are qualitative in nature, given the fitting of separate models rather than within a single multigroup model.

For these analyses, we excluded participants with missing data for sexual orientation (n = 17). This yielded a final analytic sample of 10,406 male college students. All data management and analyses were performed using SAS (SAS version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). These analyses were considered secondary analysis of anonymous data and therefore deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board review. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approved all CSHS data collection.

RESULTS

Overall, most of our analytic sample was heterosexual (92.8%), 0.7% were discordant heterosexual, 3.2% were gay, 1.5% were bisexual, and 1.7% were unsure of their sexuality. Most of the sample attended a 4-year school (65.0%), most were white (79.8%), and the median age was 22 years.

Prevalence of weight-related behaviors by sexual orientation is presented in Table 1. Overall, most males, regardless of sexual orientation, reported healthy levels of soda, diet soda, fast food, and restaurant food consumption, but few met recommendations for fruit and vegetable consumption. Across all sexual orientation groups, less than half ate breakfast at least 5 d/wk and 18% to 31% met recommendations for moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Heterosexual males had the highest proportion of participants engaging in ≥2.5 h/wk of strengthening physical activity (35.2%), whereas less than 30% of males in other sexual orientation groups met recommendations. About half of males met recommendations for screen time. Most male students did not engage in unhealthy weight control behaviors or binge eating (85.5%–95.6% reported no unhealthy weight control, 74.8%–88.6% reported no binge eating).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Weight-Related Behaviors by Sexual Orientation Among Males, College Student Health Survey 2009–2013

| Heterosexual, % (n = 9659) |

Discordant Heterosexual, % (n = 70) |

Gay, % (n = 337) |

Bisexual, % (n = 161) |

Unsure, % (n = 178) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit and vegetable consumption (≥5 per d) | 15.6 | 10.1 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 20.3 |

| Regular soda consumption (<1 per d) | 79.5 | 82.9 | 85.2 | 78.9 | 79.2 |

| Diet soda consumption (<1 per d) | 90.6 | 82.9 | 85.5 | 86.3 | 88.2 |

| Fast food consumption (<several times per wk) | 80.7 | 88.4 | 82.5 | 83.2 | 89.3 |

| Restaurant food consumption (<several times per wk) | 88.5 | 92.8 | 77.5 | 83.2 | 89.3 |

| Breakfast consumption (≥5 d/wk) | 40.3 | 39.1 | 44.2 | 37.4 | 38.8 |

| Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (≥5 h/wk of moderate and vigorous physical activity combined or ≥4.5 h/wk of either moderate or vigorous physical activity) |

35.2 | 30.0 | 24.0 | 23.0 | 25.8 |

| Strengthening physical activity (≥2.5 h/wk) | 27.7 | 18.6 | 17.8 | 14.3 | 19.9 |

| Screen time (<14 h/wk) | 48.1 | 51.4 | 53.7 | 49.7 | 54.5 |

| Unhealthy weight control behaviors (none)* | 95.6 | 85.5 | 89.0 | 93.2 | 88.2 |

| Binge eating (none) | 88.6 | 82.6 | 78.3 | 74.8 | 87.5 |

Includes taking diet pills, laxatives, or vomiting.

Fit statistics for LCA models for each individual sexual orientation group are presented in Table 2. In addition to examining fit statistics, we considered the interpretability of solutions in selecting final models. For heterosexual males, fit statistics continued to improve with increasing number of classes. However, the additional gains in information criteria (i.e., AIC, BIC, and adjusted BIC) were much lower after the four-class solution. The five-class solution did not yield a new substantive class over the four-class solution, whereas the four-class solution identified a unique subgroup over the three-class solution. Therefore, the four-class solution appeared to be an optimal solution for heterosexual males. For discordant heterosexual males, AIC and adjusted BIC suggested a three-class solution, whereas BIC and BLRT results suggested a one-class solution. The three-class solution identified classes with few members (n < 10). Compared with the one-class solution, there was a unique class identified in the two-class solution and the prevalence was adequate; therefore, a two-class solution was retained. Among gay males, fit statistics suggested varying solutions. We examined the three-, four-, and five-class solutions and found the four-class solution to be the most interpretable. For bisexual males, the AIC, adjusted BIC, and BLRT results suggest a three-class solution. This was also supported by the interpretability of the solution. Finally, for unsure participants, the four-class solution was retained based on interpretability of the solution compared with the three- and five-class solutions.

Table 2.

Fit Statistics for Unconditional Independent Latent Class Analysis Models Across Sexual Orientation†

| Likelihood | AIC | BIC | Adjusted BIC | Entropy R2 | BLRT* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual (n = 9659) | ||||||

| 1 class | −39714.80 | 3693.61 | 3758.19 | 3729.59 | 1.00 | |

| 2 classes | −38903.75 | 2091.52 | 2227.86 | 2167.48 | 0.48 | 0.01 |

| 3 classes | −38495.72 | 1295.46 | 1503.55 | 1411.39 | 0.54 | 0.01 |

| 4 classes | −38361.22 | 1046.45 | 1326.30 | 1202.36 | 0.62 | 0.01 |

| 5 classes | −38272.63 | 889.27 | 1240.88 | 1085.16 | 0.62 | 0.01 |

| 6 classes | −38215.68 | 795.36 | 1218.73 | 1031.23 | 0.58 | 0.01 |

| Discordant heterosexual (n = 70) | ||||||

| 1 class | −289.81 | 146.02 | 166.25 | 137.91 | 1.00 | |

| 2 classes | −279.19 | 144.78 | 187.51 | 127.66 | 0.66 | 0.11 |

| 3 classes | −267.40 | 141.20 | 206.40 | 115.06 | 0.85 | 0.01 |

| 4 classes | −259.12 | 144.65 | 232.34 | 109.50 | 0.90 | 0.09 |

| 5 classes | −254.42 | 155.25 | 265.43 | 111.09 | 0.88 | 0.61 |

| 6 classes | −249.48 | 165.36 | 298.02 | 112.18 | 0.89 | 0.27 |

| Gay (n = 337) | ||||||

| 1 class | −1485.22 | 345.62 | 380.00 | 351.45 | 1.00 | |

| 2 classes | −1460.02 | 315.22 | 387.80 | 327.53 | 0.70 | 0.01 |

| 3 classes | −1443.52 | 302.22 | 413.00 | 321.01 | 0.75 | 0.02 |

| 4 classes | −1426.31 | 287.81 | 436.79 | 313.08 | 0.76 | 0.01 |

| 5 classes | −1413.13 | 281.44 | 468.62 | 313.19 | 0.73 | 0.03 |

| 6 classes | −1401.87 | 278.93 | 504.31 | 317.16 | 0.72 | 0.03 |

| Bisexual (n = 161) | ||||||

| 1 class | −681.31 | 239.41 | 267.14 | 238.65 | 1.00 | |

| 2 classes | −658.32 | 213.43 | 271.97 | 211.83 | 0.92 | 0.01 |

| 3 classes | −638.26 | 193.30 | 282.66 | 190.85 | 0.73 | 0.01 |

| 4 classes | −630.06 | 196.90 | 317.07 | 193.61 | 0.71 | 0.33 |

| 5 classes | −622.57 | 201.94 | 352.92 | 197.80 | 0.75 | 0.46 |

| 6 classes | −616.34 | 209.46 | 391.26 | 204.49 | 0.77 | 0.47 |

| Unsure (n = 178) | ||||||

| 1 class | −715.74 | 272.79 | 301.42 | 272.92 | 1.00 | |

| 2 classes | −692.78 | 246.86 | 307.32 | 247.15 | 0.67 | 0.01 |

| 3 classes | −677.04 | 235.38 | 327.65 | 235.81 | 0.78 | 0.01 |

| 4 classes | −664.93 | 231.16 | 355.25 | 231.74 | 0.80 | 0.08 |

| 5 classes | −654.71 | 230.73 | 386.64 | 231.46 | 0.80 | 0.09 |

| 6 classes | −647.01 | 235.33 | 423.06 | 236.21 | 0.77 | 0.21 |

AIC indicates Akaike information criteria; BIC, Bayesian information criteria; and BLRT, bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

Bolded classes indicate final selected models.

p value represents test for a (k + 1)-class solution vs. a k-class solution (e.g., 3-class compared with 2-class, 4-class compared with 3-class).

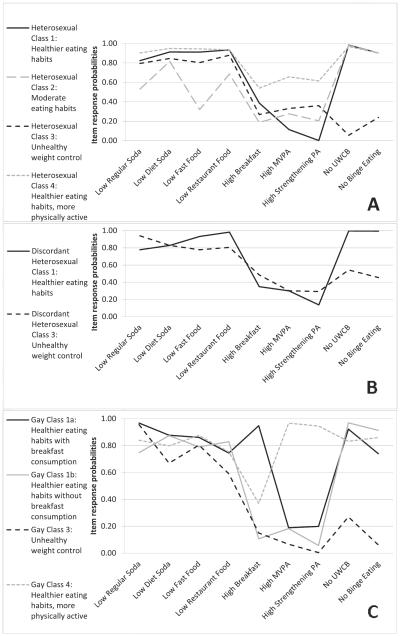

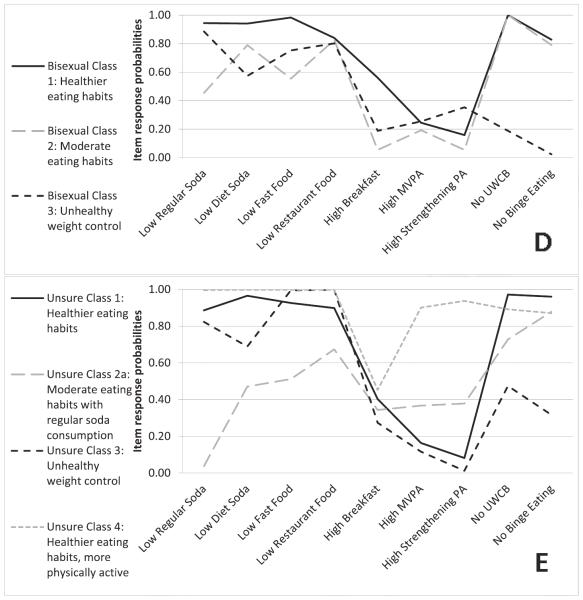

Item-response probabilities and patterning of classes are presented in the Figure. Item-response probabilities closer to one represent a high probability of engaging in healthy weight-related behaviors, whereas probabilities closer to zero indicate less favorable engagement in weight-related behaviors. A total of four general classes were identified across the five LCA models, and they can be broadly characterized as “healthier eating habits,” “moderate eating habits,” “unhealthy weight control,” and “healthier eating habits, more physically active.” As noted below, however, some deviations exist in these classes across sexual orientation groups, and not all classes were identified in all sexual orientation groups.

Class 1 (“healthier eating habits”) was characterized by a high probability of healthful levels of regular soda (<1 per day), diet soda (<1 per day), fast food (<several times per week), and restaurant food (<several times per week) consumption among all sexual orientation groups (heterosexual, .82–.93; discordant heterosexual, .78–.98; gay, .74–.97; bisexual, .84–.98; unsure, .89–.97); a low probability of meeting physical activity recommendations (range across all sexual orientation groups: moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, .11–.30; strengthening physical activity, 0–.20); and high probabilities of engaging in no unhealthy weight control behaviors or binge eating (no unhealthy weight control, .92–1.00; no binge eating, .74–.99). A deviation existed for breakfast consumption among gay males. For the “healthier eating habits” class identified among heterosexual, discordant heterosexual, bisexual, and unsure males, probabilities for meeting breakfast consumption ranged from .35 to .56. For gay men, two patterns were identified that were consistent with the “healthier eating habits” pattern for all indicators except for breakfast consumption. Class 1a (“healthier eating habits with breakfast consumption”) had a very high probability of meeting breakfast recommendations (.95), whereas class 1b (“healthier eating habits without breakfast consumption”) had a very low probability of meeting breakfast recommendations (.11).

Class 2 (“moderate eating habits”) had patterning similar to class 1 on physical activity measures, unhealthy weight control behaviors, and binge eating. However, this class was characterized by lower probabilities of healthful levels of fast food consumption (<1 per day; .32–.55), restaurant food consumption (<1 per day; .67–.83), and eating breakfast (≥5 d/wk; .05–.34). Among heterosexual and bisexual males in the “moderate eating habits” class, probabilities ranged from .45 to .53 for regular soda consumption. Among unsure males, a class 2a (“moderate eating habits with regular soda consumption”) was identified as a slight variation on the general “moderate habits” pattern. The probability of regular soda consumption among unsure males in this class was .04, suggesting very frequent consumption of regular soda among these males. A “moderate eating habits” pattern was not identified for discordant heterosexual and gay males.

Class 3 (“unhealthy weight control”) also had patterning similar to class 1; however, similarities were only for eating habits and physical activity. Class 3 was characterized by a lower probability of meeting recommendations for unhealthy weight control behaviors (range for heterosexual, gay, bisexual, and unsure, .05–.54) and binge eating (.02–.45). A class 3 pattern was identified for all sexual orientation groups. However, among discordant heterosexual males the probabilities were slightly higher than for other groups (unhealthy weight control behaviors, .54; binge eating, .45).

Class 4 (“healthier eating habits, more physically active”) was observed for heterosexual, gay, and unsure men. Class 4 had similarly high probabilities for all indicators, except for physical activity, to class 1. Class 4 was distinguishable by having the highest probabilities on meeting recommendations for physical activity compared with other classes (moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, .58–.97; strengthening physical activity, .62–.95). Heterosexual males had slightly lower probabilities than both gay and unsure males (moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, .58; strengthening physical activity, .62).

In addition to examining patterning, it is also important to assess the prevalence of each class (Table 3). The prevalence of class 1 (“healthier eating habits”), including class 1a and class 1b, ranged from 37.0% to 69.1%, and class 2 (“moderate eating habits”), including class 2a, ranged from 11.5% to 30.7%. Class 3 (“unhealthy weight control”) generally had lower prevalence, which ranged from 2.3% to 30.9%. Class 4 (“healthier eating habits, physically active”) accounted for more than one third of heterosexual men and about one tenth of gay and unsure men. Overall, there was a significant association (p < .001) between the four classes identified and BMI, with lower BMI levels in the classes with healthier behavior patterns, as expected (mean BMI: class 1, 25.9 kg/m2; class 2, 26.2 kg/m2; class 3, 27.0 kg/m2; class 4, 25.4 kg/m2).

Table 3.

Probability of Latent Class Membership*

| No. | Class 1: Healthier Eating Habits, % |

Class 1a: Healthier Eating Habits With Breakfast Consumption, % |

Class 1b: Healthier Eating Habits Without Breakfast Consumption |

Class 2: Moderate Eating Habits |

Class 2a: Moderate Eating Habits With Regular Soda Consumption |

Class 3: Unhealthy Weight Control |

Class 4: Healthier Eating Habits More Physically Active |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual | 9659 | 41.0 | 19.6 | 2.3 | 37.2 | |||

| Discordant heterosexual | 70 | 69.1 | 30.9 | |||||

| Gay | 337 | 37.0 | 47.7 | 7.2 | 8.1 | |||

| Bisexual | 161 | 61.1 | 30.7 | 8.2 | ||||

| Unsure | 178 | 67.6 | 11.5 | 10.6 | 10.2 |

Empty cells indicate class not identified.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that among male college students four general classes exist across all sexual orientation groups: class 1 (“healthier eating habits”), class 2 (“moderate eating habits”), class 3 (“unhealthy weight control”), and class 4 (“healthier eating habits, more physically active”). Variations on these classes include class 1a (“healthier eating habits with breakfast consumption”) and class 1b (“healthier eating habits without breakfast consumption”) among gay males, as well as class 2a (“moderate eating habits with regular soda consumption”) among unsure males. All sexual orientation groups exhibited an “unhealthy weight control” pattern and some variation of a “healthier eating habits” pattern.

One major area of concern high-lighted by our findings was that between 4 and 15 times the proportion of discordant heterosexual, gay, bisexual, and unsure males exhibited the “unhealthy weight control” pattern compared with heterosexual males. These findings were consistent with previous research.6–15 Further, unhealthy weight control co-occurred with low physical activity, suggesting the need for interventions addressing issues around physical activity and unhealthy weight control that are tailored specifically for nonheterosexual and discordant heterosexual college males. There has been a limited amount of work that has explored unhealthy weight control among males67–71; the focus of such work has been predominantly on females.72–79 Our study highlights the need for interventions related to unhealthy weight control among a subset of males who are disproportionately impacted by these behaviors. Interventions could include greater resources on college campuses, such as increased screening and treating of unhealthy weight control behaviors among males at campus clinics.

A second major area of concern highlighted by these findings was that a much larger proportion of heterosexual males exhibited a “healthier eating habits, more physically active” pattern than other sexual orientation groups. Most notably, no profile with high physical activity was identified for discordant heterosexual and bisexual men. Although this profile was identified for both gay and unsure men (with higher probabilities for physical activity than heterosexual men: .90–.97 vs. .61–.66), the proportion of gay and unsure men who exhibited this profile was strikingly small compared with heterosexual men (8.1% and 10.2% vs. 37.2%). This finding was consistent with previous research suggesting lower physical activity among gay and bisexual men3,19,20 and highlights the need for a physical activity promotion intervention that is targeted specifically to college males who are not exclusively heterosexual.

Sexual orientation disparities in weight-related behavior profiles, specifically with regard to physical activity and unhealthy weight control behaviors, suggest a need for interventions that are designed specifically to address some of the psychosocial factors and unique contexts related to sexual orientation. Consistent with a robust body of work and national and international guidelines on social determinants of health as a strategy for addressing health disparities as well as weight-related behaviors (especially physical activity), a multilevel approach with a focus on social conditions is most likely needed in order to address disparities.1,80–83 For example, research among college students has found that general individual-level barriers to physical activity included negative gym experiences, bad weather, and lack of time, motivation, and social support.84 To address some of these individual barriers, structural barriers may need to be addressed. For example, facilities such as college recreation centers need to be safe, supportive spaces in order to help address issues related to negative gym experiences that may prohibit physical activity for some students. However, more research is needed in order to determine the most effective interventions on college campuses to address sexual orientation disparities in weight-related behaviors.

Further, there were unique patterns that emerged in the form of two minor deviations in patterning of class 1, specifically around breakfast consumption. For most of the college male population, breakfast consumption was an area that needs to be addressed in order to improve overall eating habits in this population. Only one pattern, exhibited by nearly 37.0% of gay males (class 1a: “healthier eating habits with breakfast consumption”), had high probabilities of breakfast consumption compared with other patterns and other sexual orientation groups, thus representing an area in which a subset of gay males are doing very well with regard to guidelines for healthy eating. Overall, breakfast interventions are needed at the college level (i.e., across sexual orientation groups). Breakfast intervention efforts have focused on primary and secondary school children through initiatives such as the School Breakfast Program,85 and have included measures such as offering breakfast before school, breakfast in the class-room, and Grab n’ Go breakfast options.85–87 Future work should explore breakfast intervention options for different college settings (such as 2- year vs. 4-year schools) in order to improve dietary habits among all students.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use LCA to examine disparities in weight-related behaviors across sexual orientation among males. A strength of this study includes the large sample of gay, bisexual, and unsure participants (which allowed separate sexual orientation groups rather than treating all nonheterosexual participants as a homogenous group), who have been shown in previous research to be at increased risk in comparison with their consistently heterosexual peers.16,46,88,89 The sample size allowed for a more robust and fine-grain examination of sexual orientation disparities. However, for discordant heterosexual males in particular, it may not have been sufficient to identify additional salient classes, such as a “healthier eating habits, more physically active” profile. Future studies with large samples for these groups are needed to confirm our findings. Further, future work should explore the intersection of weight status and sexual orientation in the creation of weight-related profiles. Because of the differing number of classes identified (indicating differences in latent class structure) by sexual orientation group as well as the discrepancies in the breakfast, regular soda, and diet soda indicators among gay and unsure males, we were not able to quantitatively assess differences using significance testing. However, the findings of this study still highlight important differences across sexual orientation that are useful for future intervention development. Further, some questions used in the survey may not have been specific or clear enough to the respondent (e.g., fast food consumption) and could have resulted in some error. Finally, because this was a population-based sample of college students in Minnesota, the results are not generalizable to college students in other geographic areas or to young adults not attending a postsecondary institution.

Overall, these findings highlight unique patterning of weight-related behaviors across sexual orientation groups among college males. Among all college males, interventions are needed to address physical activity and unhealthy weight control behaviors, although a focus is needed for discordant heterosexual, gay, bisexual, and unsure males, for whom these behaviors are more prevalent. Future research should examine patterning using other large data sets across diverse sexual orientation groups. Future intervention work can benefit from these findings by tailoring intervention components and targeting recruitment to specific patterns of weight-related behaviors as well as to specific sexual orientation groups.

SO WHAT? Implications for Health Promotion Practitioners and Researchers

What is already known on this topic?

Existing research suggests that gay men may be more likely to engage in unhealthy weight control behaviors and potentially less likely to engage in physical activity.

What does this article add?

This article examines patterns of weight-related behaviors and differences across sexual orientation. Only among heterosexual males was a subgroup characterized by healthier eating and engagement in physical activity, suggesting the need for physical activity and healthier eating interventions, particularly for discordant heterosexual, gay, bisexual, and unsure college males.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Intervention strategies should incorporate multiple weight-related behaviors in order to more effectively address weight-related health. Further, interventions should be targeted to specific sexual orientation groups in order to address some of the unique disparities experienced by certain groups. Additionally, more research is needed in order to understand the unique contexts of weight-related behavioral disparities across sexual orientation in order to better develop interventions that address these disparities.

Figure. Item-Response Probabilities* Across Sexual Orientation Groups (A: Heterosexual, B: Discordant Heterosexual, C: Gay, D: Bisexual, and E: Unsure).

* Item-response probabilities of 0.0 reflect unhealthy weight-related behaviors in a class and probabilities of 1.0 reflect healthy weight-related behaviors in a class. MVPA indicates moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA, physical activity; and UWCB, unhealthy weight control behaviors.

Acknowledgments

At the time of this study, N.A.V. was a graduate school trainee with the Division of Epidemiology and Community Health at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health. The study was supported primarily by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award no. R21HD073120 (PI: M.N.L.). Further support on this project was also provided by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases award no. T32 DK083250. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Nicole A. VanKim, Institute for Behavioral and Community Health, San Diego State University, San Diego, California.

Darin J. Erickson, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Marla E. Eisenberg, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Katherine Lust, Boynton Health Service, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

B. R. Simon Rosser, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Melissa N. Laska, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1953–1960. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dilley JA, Simmons KW, Boysun MJ, et al. Demonstrating the importance of feasibility of including sexual orientation in public health surveys: health disparities in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deputy NP, Boehmer U. Weight status and sexual orientation: differences by age and within racial and ethnic subgroups. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:103–109. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deputy NP, Boehmer U. Determinants of body weight among men of different sexual orientations. Prev Med. 2010;51:129–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakkis J, Ricciardelli LA, Williams RJ. Role of sexual orientation and gender-related traits in disordered eating. Sex Roles. 1999;41:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell CJ, Keel PK. Homosexuality as a specific risk factor for eating disorders in men. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:300–306. doi: 10.1002/eat.10036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman MB, Meyer IH. Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:218–226. doi: 10.1002/eat.20360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlat DJ, Camargo CA, Herzog DB. Eating disorders in males: a report on 135 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1127–1132. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen AE. Eating disorders in gay males. Psychiatr Ann. 1999;29:206–212. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brand PA, Rothblum ED, Soloman LJ. A comparison of lesbians, gay men, and heterosexuals on weight and restrained women. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;11:253–259. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey JA, Robinson JD. Eating disordersal in men: current considerations. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2003;10:297–306. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strong SM, Williamson DA, Netemeyer RG, Geer JH. Eating disorder symptoms and concerns about body differ as a function of gender and sexual orientation. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2000;19:240–255. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yelland C, Tiggemann M. Muscularity and the gay ideal: body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in homosexual men. Eat Behav. 2003;4:107–116. doi: 10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hospers HJ, Jansen A. Why homosexuality is a risk factor for eating disorders in males. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2005;24:1188–1201. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laska MN, VanKim NA, Erickson DJ, et al. Disparities in weight and weight behaviors by sexual orientation in college students. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:111–121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin SB, Ziyadeh NJ, Corliss HL, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in purging and binge eating from early to late adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehmer U, Miao X, Linkletter C, Clark MA. Adult health behaviors over the life course by sexual orientation. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:292–300. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosario M, Corliss HL, Everett BG, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in cancer-related risk behaviors of tobacco, alcohol, sexual behaviors, and diet and phyiscal activity: pooled Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:245–254. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calzo JP, Roberts AL, Corliss HL, et al. Physical activity disparities in heterosexual and sexual minority youth ages 12-22 years old: roles of childhood gender nonconformity and athletic self-esteem. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laska MN, Pasch KE, Lust K, et al. The differential prevalence of obesity and related behaviors in two- vs. four-year colleges. Obesity. 2011;19:453–456. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention BRFSS prevalence data – age grouping. Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/age.asp?cat=OB&yr=2013&qkey=8261&state=UB. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- 23.Harris KM, Gordon-Larsen P, Chantala K, Udry JR. Longitudinal trends in race/ ethnic disparities in leading health indicators from adolescence to young adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:74–81. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson MC, Story M, Larson NI, et al. Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: an overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity. 2008;16:2205–2211. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park MJ, Mulye TP, Adams SH, et al. The health status of young adults in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon-Larsen P, The NS, Adair LS. Longitudinal trends in obesity in the United States from adolescence to the third decade of life. Obesity. 2010;18:1801–1804. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M. Trends in adolescent fruit and vegetable consumption, 1999–2004: project EAT. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popkin BM. Patterns of beverage use across the lifecycle. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, et al. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Popkin BM. Longitudinal physical activity and sedentary behavior trends: adolescence to adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson MC, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, et al. Longitudinal and secular trends in physical activity and sedentary behavior during adolescence. Pediatrics. 2006;118:E1627–E1634. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caspersen CJ, Pereira MA, Curran KM. Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age. Med Sci Sport Med. 2000;32:1601–1609. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:875–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36:385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Igartua K, Thombs BD, Burgos G, Montoro R. Concordance and discrepancy in sexual identity, attraction, and behavior among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Braun L. Sexual identity development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: consistency and change over time. J Sex Res. 2006;43:46–58. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Center for Education Statistics Enrollment rates of 18- to 24-year-olds in degree-granting institutions, by level of institution and sex and race/ethnicity of student: 1967 through 2012. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_302.60.asp. Accessed June 24, 2014.

- 39.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, et al. Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: results from a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1802–1809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boehmer U, Bowen DJ, Bauer GR. Overweight and obesity in sexual-minority women: evidence from population-based data. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1134–1140. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowen DJ, Balsam KF, Ender SR. A review of obesity issues in sexual minority women. Obesity. 2008;16:221–228. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.French SA, Story M, Remafedi G, et al. Sexual orientation and prevalence of body dissatisfaction and eating disordered behaviors: a population-based study of adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19:119–126. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199603)19:2<119::AID-EAT2>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9–12 – Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, Selected Sites, United States, 2001–2009. MMWR. 2011;60:1–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Austin SB, Nelson LA, Birkett MA, et al. Eating disorder symptoms and obesity at the intersections of gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation in US high school students. Am J Public Health. 2012;103:16–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.VanKim NA, Erickson DJ, Eisenberg ME, et al. Weight disparities for transgender college students. Health Behav Policy Rev. 2014;1:161–171. doi: 10.14485/HBPR.1.2.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corliss HL, Goodenow CS, Nichols L, Austin SB. High burden of homelessness among sexual-minority adolescents: findings from a representative Massachusetts high school sample. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1683–1689. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.US Dept of Health and Human Services. US Dept of Agriculture . Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ledoux TA, Hingle MD, Baranowski T. Relationship of fruit and vegetable intake with adiposity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e143–e150. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timlin MT, Pereira MA. Breakfast frequency and quality in the etiology of adult obesity and chronic diseases. Nutr Rev. 2007;65(6):268–281. doi: 10.1301/nr.2007.jun.268-281. pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ebbeling CB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2014;25:1–7. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nago ES, Lachat CK, Dossa RA, Kolsteren PW. Association of out-of-home eating with anthropometric changes: a systematic review of prospective studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54(9):1103–1116. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.627095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lachat CK, Nago ES, Verstraeten R, et al. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev. 2012;13:329–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm Accessed January 23, 2006.

- 54.Nelson MC, Lytle LA. Development and evaluation of a brief screener to estimate fast food and beverage consumption among adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:730–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nelson MC, Lust K, Story M, Ehlinger E. Credit card debt, stress and key health risk behaviors among college students. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22:400–407. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.6.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young LR, Nestle M. The contribution of expanding portion sizes to the US obesity epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:246–249. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diliberti N, Bordi PL, Conklin MT, et al. Increased portion size leads to increased energy intake in a restaurant meal. Obes Res. 2004;12:562–568. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.US Dept of Health and Human Services. US Dept of Agriculture . Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6th US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 59.VanKim NA, Laska MN, Ehlinger E, et al. Understanding young adult physical activity, alcohol and tobacco use in community colleges and 4-year post-secondary institutions: a cross-sectional analysis of epidemiological surveillance data. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.American Academy of Pediatrics Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107:423–426. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laska MN, Pasch KE, Lust K, et al. Latent class analysis of lifestyle characteristics and health risk behaviors among college youth. Prev Sci. 2009;10:376–386. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0140-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nelson MC, Lust K, Story M, Ehlinger E. Alcohol use, eating patterns, and weight behaviors in a university population. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33:227–237. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Austin SB, Ziyadeh NJ, Kahn JA, et al. Sexual orientation, weight concerns, and eating-disordered behaviors in adolescent girls and boys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1115–1123. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000131139.93862.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. John Wiley & Sons Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCutcheon AL. Latent Class Analysis. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berlin KS, Williams NA, Parra GR. An introduction to latent varibale mixture modeling (part 1): overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013:1–14. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: relationship to gender and ethnicity. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:166–175. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van den Berg PA, Mond J, Eisenberg ME, et al. The link between body dissatisfaction and self-esteem in adolescents: similarities across gender, age, weight status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing the broad spectrum of weight-related problems: working with parents to help teens achieve a healthy weight and a positive body image. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2005;37(suppl 2):S133–S140. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C. The role of social norms and friends’ influences on unhealthy weight-control behaviors among adolescent girls. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1165–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall MM, Story M, Perry CL. Correlates of unhealthy weight-control behaviors among adolescents: implications for prevention programs. Health Psychol. 2003;22:88–98. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stice E, Orjada K, Tristan J. Trial of psychoeducational eating disturbance intervention for college women: a replication and extention. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39:233–239. doi: 10.1002/eat.20252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodgers R, Chabrol H. Parental attitudes, body image disturbance and disordered eating amongst adolescents and young adults: a review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2009;17:137–151. doi: 10.1002/erv.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stice E, Shaw HE. Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:985–993. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stice E, Whitenton K. Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: a longitudinal investigation. Dev Psychol. 2002;38(5):669–678. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stice E, Hayward C, Cameron RP, et al. Body image and eating disturbances predict onset of depression among female adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Paikoff RL, Warren MP. Prediction of eating problems: an 8-year study of adolescent girls. Dev Psychol. 1994;30:823–834. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zipfel S, Lowe B, Reas DL, Deter HC, Herzog W. Long-term prognosis in anorexia nervosa: lessons from a 21-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2000;355:721–722. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vogeltanz-Holmm ND, Wonderlich SA, Lewis BA, et al. Longitudinal predictors of binge eating, intense dieting, and weight concerns in a national sample of women. Behav Ther. 2000;31:221–235. [Google Scholar]

- 80.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Summary: workshop on predictors of obesity, weight gain, diet, and physical activity, 2004. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/meetings/workshops/predictors/summary.htm. Accessed October 15, 2012.

- 81.Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Dzewaltowski DA, Owen N. Toward a better understanding of the influences on physical activity: the role of determinants, correlates, causal variables, mediators, moderators, and confounders. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(suppl 2):5–14. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1793–1812. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nelson MC, Kocos R, Lytle LA, Perry CL. Understanding the perceived determinants of weight-related behaviors in late adolescence: a qualitative analysis among college youth. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.US Dept of Agriculture School Breakfast Program. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sbp/school-breakfast-program. Accessed June 8, 2014.

- 86.Basch CE. Breakfast and the achievement gap among urban minority youth. J Sch Health. 2011;81:635–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kothe EJ, Mullan B. Increasing the frequency of breakfast consumption. Br Food J. 2011;113:784–796. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Physical health complaints among lesbians, gay men, and bisexual and homosexually experienced heterosexual individuals: results from the California Quality of Life Survey. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2048–2055. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Burden of psychiatric morbidity among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in the California Quality of Life Survey. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:647–658. doi: 10.1037/a0016501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]