Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to characterize the effects of food on single-dose pharmacokinetics (PK) of the investigational Aurora A kinase inhibitor alisertib (MLN8237) in patients with advanced solid tumors.

Methods

Following overnight fasting for 10 h, a single 50 mg enteric-coated tablet (ECT) of alisertib was administered under either fasted (alisertib with 240 mL of water) or fed (high-fat meal consumed 30 min before receiving alisertib with 240 mL of water) conditions using a two-cycle, two-way crossover design. Patients on both arms were not allowed food for 4 h post-dose. Water was allowed as desired, except for 1 h before and after alisertib administration.

Results

Twenty-four patients were enrolled and 14 patients were PK-evaluable (ten patients were not PK-evaluable due to insufficient data). Following a single oral dose of alisertib, median tmax was 6 h and 3 h under fed and fasted conditions, respectively. The geometric mean ratio of AUCinf (fed- vs. fasted-state dosing) was 0.94 [90 % confidence interval (CI) 0.68–1.32]. The geometric mean Cmax under fed conditions was 84 % of that under fasted conditions (90 % CI 66–106). Alisertib was generally well-tolerated; most common drug-related grade 3/4 adverse events included neutropenia (50 %), leukopenia (38 %), and thrombocytopenia (21 %).

Conclusions

Systemic exposures achieved following a single 50 mg dose of alisertib administered as an ECT formulation after a high-fat meal are similar to those observed in the fasted state. Alisertib 50 mg ECT can be administered without regard for food.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

Key Points

| There was no readily apparent effect of food on the total systemic exposure of alisertib (MLN8237) following single-dose administration of a 50 mg enteric-coated tablet (ECT) formulation. The geometric mean ratio of the area under the curve from time zero to infinity (AUCinf) (fed vs. fasted) was 0.94 (90 % confidence interval 0.68–1.32). |

| A small (16 %) decrease in the geometric mean maximum observed plasma concentration (C max) was observed when alisertib was administered following a high-fat meal compared with under fasted conditions, and the median time to reach C max (t max) was delayed from 3 to 6 h. |

| Administration of alisertib ECT in the postprandial state is associated with a reduction in the rate of oral absorption without an effect on the extent of oral absorption. The results of this study support a recommendation that alisertib ECT may be administered without regard for food in future clinical studies unless otherwise specified in the protocols. |

Introduction

Aurora A kinase (AAK) belongs to a highly conserved family of serine/threonine protein kinases and has a critical role in the formation and function of the mitotic spindle [1]. The AAK gene is amplified and/or the protein is overexpressed in multiple types of cancer, including bladder, breast, colorectal, upper gastrointestinal (GI), head and neck, lung, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer [2–10]. Ectopic expression of AAK leads to centrosome amplification, aneuploidy, and chromosome instability [11–13], suggesting that AAK dysfunction may have the potential to drive cancer progression. Overexpression of AAK has been shown to transform normal cells, indicating oncogenic potential [3, 13].

Alisertib (MLN8237) is an investigational, oral, selective AAK inhibitor that is in development for the treatment of advanced malignancies. Phase I clinical trials of alisertib demonstrated that alisertib is generally well-tolerated, with common toxicities, including myelosuppression, fatigue, and stomatitis [14–16]. Preliminary antitumor activity has been observed in a range of solid tumors in phase I and II trials [17]. Based on these early clinical studies, the recommended phase II dose of alisertib for patients with solid tumors was determined to be 50 mg twice daily for 7 days on a 21-day cycle [14, 15].

As alisertib is administered orally, the potential impact of food intake on oral bioavailability is an important consideration. The solubility of alisertib molecules is low in acidic pH; hence, the drug was originally developed as a buffered powder-in-capsule (PIC) formulation for initial phase I clinical studies [15]. Subsequently, the enteric-coated tablet (ECT) formulation was developed and is being evaluated in multiple studies. Alisertib demonstrated linear pharmacokinetics (PK) over the dose range of 5–200 mg/day, and in clinical trials was administered on an empty stomach prior to this food-effect assessment. The effect of food intake on PK may vary with the composition of the food consumed and with potential interactions with intestinal transport mechanisms and enzymes [18, 19]. The maximum effect of food on GI physiology is likely to be observed with a high-fat, high-calorie meal [20]. Food may delay gastric emptying, change GI pH, and increase splanchnic blood flow [20, 21]. Food can also alter the bioavailability of a drug by physically or chemically interacting with that drug [20]. This study investigated the effect of a high-fat meal on the single-dose PK of alisertib administered as a 50 mg ECT formulation, and the safety and activity of alisertib 40 to 50 mg twice daily (days 1–7, 21-day cycles) in patients with advanced solid tumors.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

This study was one part of an open-label, multicenter, phase I trial to characterize the effects of food on the single-dose PK of alisertib 50 mg ECT in patients with advanced solid tumors. The study used a two-cycle, two-way crossover design. Patients were randomized, in an approximate 1:1 ratio, to receive a single 50 mg dose of alisertib following or without a standard high-fat breakfast on day 1 of cycle 1, with the respective alternate food intake condition (fasted to fed, or fed to fasted) on day 1 in cycle 2 (Fig. 1). In the fed state, patients received a standard high-fat meal approximately 30 min before dosing [54 g fat, 46 g protein, 72 g carbohydrate, 1036 calories (two fried or scrambled eggs; two strips of bacon; two slices of toasted bread with two pats of butter; 60–120 g hash brown; 24–280 mL whole milk; and one cup of coffee or tea)]. Patients were to consume at least 75 % of the meal within 30 min, including the milk). In the fasted state, patients were required to fast overnight (approximately 10 h) before receiving the single alisertib dose on day 1 of cycle 1 and day 1 of cycle 2. In both fed and fasted conditions, no (additional) food was permitted for 4 h post-dosing.

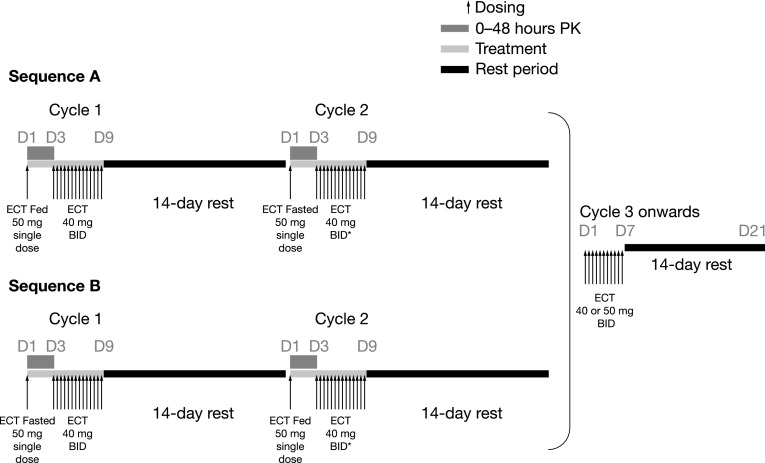

Fig. 1.

Study design. *Dose escalation to 50 mg twice daily was allowed at any point after cycle 1 based on tolerability and objective safety findings in the previous cycles (for example, no dose-limiting toxicity or grade 4 toxicity of any duration). Twenty-four patients were randomized (sequence A, n = 1 2; sequence B, n = 12). BID twice daily, D day, ECT enteric-coated tablet, PK pharmacokinetics

During the remainder of cycle 1, alisertib ECT was administered at a dose of 40 mg twice daily from day 3 to the morning dose on day 9, followed by a 14-day rest period (i.e. a total of 14 unit doses in a 23-day cycle). A dose of 40 mg twice daily (80 % of the maximum recommended dose of 50 mg twice daily [14, 15]) was used in cycle 1 to reduce the risk of potential toxicities that might prevent patients from continuing to cycle 2. Cycle 2 had the same structure as cycle 1, but the dose of alisertib on days 3–9 could be escalated to 50 mg twice daily based on tolerance of the 40 mg twice daily regimen in cycle 1. After cycle 2, alisertib (40 or 50 mg, based on the tolerance in cycle 1) twice daily was administered on days 1–7 in 21-day cycles, with the last dose on the evening of day 7, followed by a 14-day rest period.

Patients were enrolled to the study at three centers in the US. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles founded in the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The Institutional Review Board at each participating center reviewed and approved the study protocol and all authors provided written informed consent.

Patients

Key inclusion criteria included age ≥18 years; histologically or cytologically confirmed advanced solid tumor for which no effective standard treatment was available; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1; and measurable disease according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 [22]. Patients had to have recovered (to grade ≤1 or to baseline status) from the reversible effects of any previous antineoplastic therapy [graded according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI–CTCAE) version 3.0]. Patients required adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function, defined, respectively, as absolute neutrophil count ≥1500/μL and platelet count ≥100,000/μL; total bilirubin <1.5× the upper limit of normal (ULN), alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase ≤2.5× ULN (up to 5× ULN allowed if attributable to the presence of liver metastases), and albumin greater than the lower limit of normal; and creatinine clearance ≥40 mL/min (calculated as per the Cockcroft–Gault equation).

Key exclusion criteria were symptomatic brain metastases; major surgery within 14 days, or radiotherapy or antineoplastic therapy within 21 days (6 weeks for nitrosoureas or mitomycin-C); autologous stem cell transplant within 3 months or any previous allogeneic stem cell transplant; treatment with clinically significant enzyme inducers such as enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs or St John’s wort within 14 days; recurrent nausea or vomiting within 14 days; any medical condition that required use of pancreatic enzymes [daily, chronic, or regular use of protein pump inhibitor or histamine (H2) receptor antagonists]; any known GI abnormality or procedure that could interfere with or modify the oral absorption or tolerance of alisertib; an uncontrolled cardiovascular condition; any active infection requiring systemic therapy or other serious infection within 30 days; and lactose intolerance that may preclude the ability to consume the glass of whole milk, which was required to be part of the high-fat meal.

Assessments

Blood samples for PK assessment were taken in cycles 1 and 2, immediately before the day 1 single dose of alisertib, and at 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 24, and 48 h after dosing, with the 48 h post-dose sample taken before dosing on day 3. Alisertib plasma concentrations were measured using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, as described by Dees et al. [15].

Tumor response was assessed based on RECIST version 1.1 [22] at baseline, at the end of cycles 2, 4, and 6, and thereafter every 3 cycles (9 weeks) until disease progression. Regular safety assessments included hematology, clinical chemistry, vital signs, and ECOG performance status. Adverse events (AEs) were monitored throughout the study and graded using NCI–CTCAE version 3.0.

Statistical Methods

The PK-evaluable population included patients who received the single 50 mg doses of alisertib in cycles 1 and 2 and completed all the necessary PK evaluations following each day 1 dose. Patients who vomited within 6 h of taking the day 1 dose of alisertib, and patients who have taken medication that could compromise the PK assessments, were excluded from the PK-evaluable population. A sample size of 14 patients completing the protocol-specified PK evaluations was needed (evaluable patients were to consume at least 75 % of the meal, including the milk), based on the expected precision in estimating the ratio of geometric mean area under the concentration curve (AUC) and maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax) of alisertib in the fed versus fasted states. PK parameters were calculated by non-compartmental analysis using WinNonlin Enterprise version 5.3. Statistical analysis of PK parameters was performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics for plasma concentrations and PK parameters, including Cmax, time to Cmax (tmax), area under the curve from time zero to last determined concentration-time (AUCtlast), and area under the curve from time zero to infinity (AUCinf) were tabulated by fed or fasted condition. To estimate the effect of food on alisertib PK, the geometric mean ratios for fed versus fasted conditions of AUCtlast, AUCinf, and Cmax, as well as associated two-sided 90 % confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated based on the within-patient variance using analysis of variance (ANOVA) on log-transformed AUC and Cmax data, with food effect, sequence, and period as fixed effects, and patient as random effect.

Results

In total, 24 patients were enrolled. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 57.5 years (range 39–72), and most patients were heavily pretreated, with 75 % of patients having received three or more previous lines of systemic therapy.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| N = 24 | |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 57.5 (39–72) |

| Male/female sex [n (%)] | 8/16 (33/67) |

| Race [n (%)] | |

| Caucasian | 23 (96) |

| Black or African American | 1 (4) |

| ECOG performance status [n (%)] | |

| 0 | 7 (29) |

| 1 | 17 (71) |

| Mean weight, kg (SD) | 69.5 (18.9) |

| Weight range, kg | 43–101 |

| Mean BSA, m2 (SD) | 1.8 (0.3) |

| BSA range, m2 | 1.4–2.2 |

| Cancer type [n (%)] | |

| Colorectal | 6 (25) |

| Cervical | 4 (17) |

| Melanoma | 2 (8) |

| NSCLC | 2 (8) |

| Ovarian | 2 (8) |

| Pancreatic | 2 (8) |

| Othera | 6 (25) |

| ≥3 prior lines of therapy [n (%)] | 18 (75) |

| Most frequent prior systemic therapies [n (%)] | |

| Carboplatin | 10 (42) |

| Paclitaxel | 10 (42) |

| Bevacizumab | 9 (38) |

BSA body surface area, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology group, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, SD standard deviation

aAdrenal, breast, prostate, leiomyosarcoma, small cell lung cancer, and peritoneal carcinoma (n = 1 each)

Patients received a median of three cycles of alisertib (range 1–11). Twenty-three (96 %) patients completed at least two cycles of alisertib, and seven patients (29 %) received six or more cycles. At data cut-off (28 December 2011) treatment was ongoing in six patients (25 %), and 18 patients (75 %) had discontinued treatment because of disease progression (n = 14), symptomatic deterioration (n = 3), or withdrawal of consent (n = 1).

Among the 24 enrolled patients (fed/fasted, n =12; fasted/fed, n = 12), 14 patients (fed/fasted, n = 8; fasted/fed, n = 6) completed the protocol-specified dosing and PK assessments in both periods of the study necessary for the two-cycle crossover food-effect analysis (the terminal phase of alisertib plasma concentration–time profile was not sufficiently defined in three patients; AUCinf parameters are presented for n = 11).

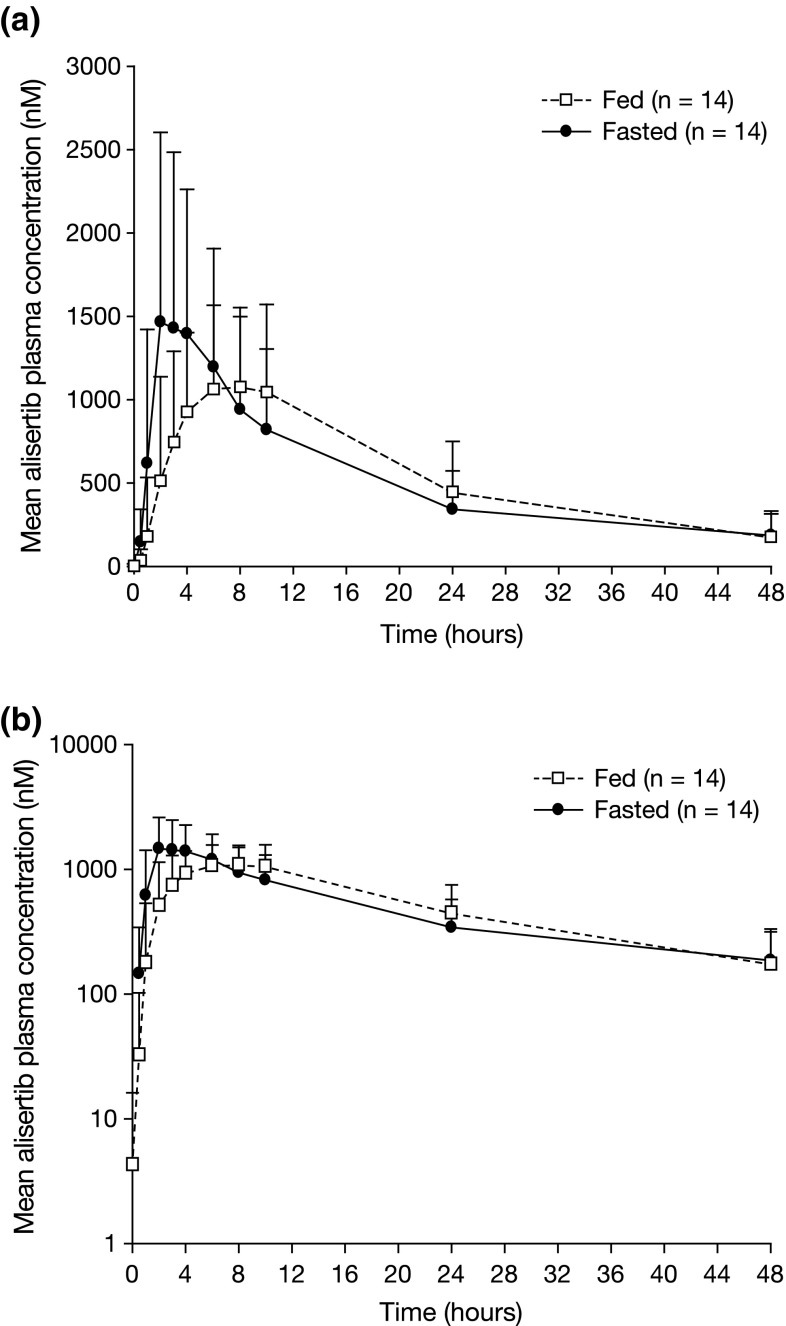

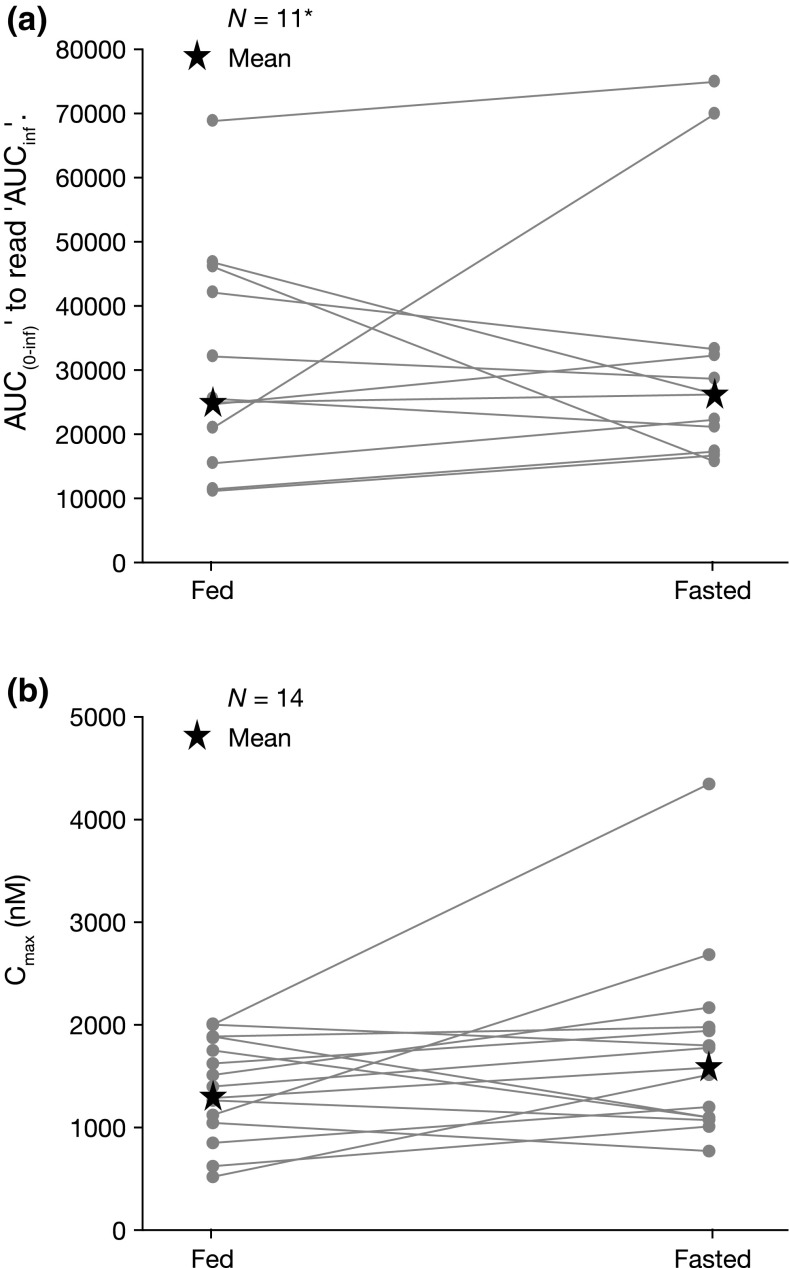

Following oral dosing of alisertib under the fed state, a delay in absorption was observed, with a median tmax of approximately 6 h following dosing in the postprandial state, compared with 3 h following dosing in the fasted state (Fig. 2; Table 2). The geometric mean Cmax under fed conditions was 84 % of that under fasted conditions (90 % CI 66–106 %) (Table 2). The geometric mean AUCinf following single-dose alisertib under fed conditions was 94 % of that under fasted conditions (90 % CI 68–132 %) (Table 2). Cmax and AUCinf individual patient values under fed and fasted conditions are shown in Fig. 3. The mean terminal half-life (t½) of alisertib was similar under fed and fasted conditions (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean alisertib plasma concentration–time profiles following single-dose administration of alisertib ECT 50 mg in the fed (n = 14) or fasted state (n = 14) on a a linear scale and b a semi-logarithmic scale. ECT enteric-coated tablet

Table 2.

Summary of key alisertib pharmacokinetic parameters in the fed and fasted states

| Parameter | Alisertib 50 mg | Geometric mean ratio, fed versus fasted (90 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fed state (n = 14) | Fasted state (n = 14) | ||

| Median t max, h (range) | 6.0 (1.9–9.0) | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) | – |

| Mean t ½, h (SD) | 14.9 (4.8) | 16.7 (4.4)a | – |

| Geometric mean C max, nM (CV %) | 1299.9 (36) | 1583.8 (53) | 0.84 (0.66–1.06) |

| Geometric mean AUCtlast, nM*h (CV %) | 21,673.93 (49) | 21,183.04 (60) | 1.04 (0.80–1.34) |

| Geometric mean AUCinf, nM*h (CV %) | 24,934.1 (55) | 26,190.8 (69)a | 0.94 (0.68–1.32) |

AUC tlast/AUC inf area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to last determined concentration-time point/infinity, C max maximum plasma concentration, CI confidence interval, CV coefficient of variation, SD standard deviation, t ½ terminal half-life, t max time to C max

a n = 11

Fig. 3.

Alisertib a AUCinf and b C max in individual patients following single-dose administration of alisertib ECT 50 mg under fed or fasted conditions. *The terminal phase of the alisertib plasma concentration–time profile was not sufficiently defined in three patients. AUC inf area under the plasma concentration–time profile from time zero to infinity, C max maximum plasma concentration, ECT enteric-coated tablet

All 24 patients received at least one dose of alisertib and were included in the safety analysis. Twenty-three patients (96 %) reported at least one drug-related AE, and drug-related grade 3 or higher AEs were reported in 16 patients (67 %) (Table 3). Most drug-related AEs were reported during the first two cycles of treatment. No patient discontinued treatment due to AEs. The most commonly reported drug-related non-hematologic AEs were alopecia (50 %), diarrhea (25 %), fatigue (21 %), and nausea (21 %). Non-hematologic toxicity was typically mild or moderate in severity (grade 1/2), and no grade 3/4 non-hematologic AEs were reported in more than one patient. Drug-related hematologic toxicity was common (Table 3). Grade 3/4 neutropenia was observed in 12 patients (50 %) and grade 3/4 leukopenia was observed in nine patients (38 %).

Table 3.

Most frequent drug-related AEs across all alisertib treatments: events of any grade reported in ≥10 % of patients and/or of grade ≥3 severity reported in ≥5 % of patients

| AE [n (%)]a | N = 24 | |

|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade ≥3 | |

| Non-hematologic | ||

| Alopecia | 12 (50) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 6 (25) | 1 (4) |

| Fatigue | 5 (21) | 1 (4) |

| Nausea | 5 (21) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 4 (17) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 4 (17) | 0 |

| AST increased | 3 (13) | 0 |

| Hematologic | ||

| Neutropenia | 17 (71) | 12 (50) |

| Leukopenia | 13 (54) | 9 (38) |

| Anemia | 7 (29) | 3 (13) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 7 (29) | 5 (21) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (8) | 2 (8) |

Criteria for Adverse Events

AE adverse event, AST aspartate aminotransferase, NCI–CTCAE National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity

aGraded according to the NCI–CTCAE version 3.0

Three patients (13 %) experienced AEs that were considered serious and related to alisertib, including grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia (n = 2) and grade 3 neutropenia (n = 1), each of which occurred during the first two cycles. One patient died during the study: a 39-year-old White female, initially diagnosed with colorectal cancer stage IIIC and who had an extensive treatment history and pulmonary metastases, died 27 days after the last dose of alisertib (administered on cycle 2, day 9). The death was considered to be due to pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer and not related to the study drug.

All 24 patients were evaluable for response. Twelve patients (50 %) had a best response of stable disease, of whom seven had stable disease lasting more than 3 months.

Discussion

Food consumption can alter oral drug bioavailability by affecting drug solubility and GI physiology [20, 23]. Studies to assess the effects of food on the rate and extent of drug absorption of oral kinase inhibitors have demonstrated that these effects may vary considerably. For example, the systemic exposures of gefitinib [24] and imatinib [25] are unaffected by food, whereas erlotinib systemic exposure approximately doubled following administration under fed conditions when compared with fasted conditions (single-dose crossover study) [26]. Lapatinib systemic exposure increased substantially when administered with food. Lapatinib AUC values were approximately three- and fourfold higher when administered with a low- or high-fat meal, respectively [27]. In contrast, the effects of food on PK may also be modest, such as with dasatinib; a 100 mg dose of dasatinib following consumption of a high-fat meal (30 min) resulted in a 14 % increase in the mean AUC of dasatinib, which was not considered to be clinically relevant [28].

Alisertib is a small molecule drug with reduced solubility in acidic solution, and the ECT formulation was developed to bypass the stomach to delay dissolution until delivery to the upper small bowel. No readily apparent or consistent effect of food was observed on the total systemic exposure of alisertib. The geometric mean ratio of AUCinf (fed- vs. fasted-state dosing) was 0.94 (90 % CI 0.68–1.32). A small (16 %) decrease in geometric mean Cmax was observed when alisertib was administered following a high-fat meal, and the median tmax was delayed from 3 to 6 h. These observations suggest that administration of alisertib ECT in the postprandial state is associated with a reduction in the rate of oral absorption without an effect on the extent of oral absorption, thereby translating to similar systemic exposures of alisertib when administered in the fed or fasted states. Food intake had no effect on alisertib AUCinf in this study. The small reduction in alisertib Cmax when administered in the fed state is not expected to be of clinical significance because the relative decrease of 16 % was well below the 36–53 % coefficient of variation in Cmax. The pharmacodynamics of alisertib, and consequently its efficacy, are thought to be related to total systemic exposure (AUC) rather than peak concentrations based on clinical exposure–pharmacodynamic relationships [14, 15], as well as non-clinical exposure–efficacy relationships [29, 30]. These data indicate that there is not a clinically meaningful effect of food intake on the PK of alisertib ECT.

Of note, this study has a few limitations. The sampling schedule was not optimal for this newly introduced ECT tablet strength (50 mg), therefore the terminal phase of alisertib concentration–time profiles for several patients was ill-characterized, and thus precluding it from reliably estimating PK parameters such as AUCinf for these patients. In addition, 10 of the 24 enrolled patients were not evaluable for food-effect assessments—eight patients were non-evaluable as a result of insufficient data for AUC calculation due to atypical absorption profiles (e.g. substantial delay in tmax) or missing key PK samples at either cycle 1, day 1, or cycle 2, day 1; one patient did not consume a protocol-specified sufficient amount of the high-fat meal, and one patient discontinued the study due to progressive disease after cycle 1. Furthermore, three patients were excluded from the analysis of AUCinf in fasted versus fed states because the terminal phases of their alisertib PK was not sufficiently defined. However, AUCt was provided for all evaluable patients, including these three patients. Thus, as shown in Table 2, AUCtlast was based on n = 14, AUCinf was based on n = 11, and the 90 % CI for AUCinf was slightly wider than that of AUCtlast. Taking these limitations into consideration, the conclusion for this food-effect study was not changed.

Alisertib was generally well tolerated, with no unexpected toxicities. The reported hematologic toxicities were consistent with what has been observed in other studies with this agent [14, 15, 17]. The predominant toxicities that were observed reflect the effects of alisertib in highly proliferative normal tissue, including the bone marrow, GI epithelium, and hair follicles. The clinical experience to date in multiple studies of alisertib has demonstrated that major toxicities can typically be managed sufficiently to permit continued treatment over an extended period of time, including up to 24 months [15].

Conclusions

The results of this study support a recommendation that alisertib may be administered without regard to the timing of meals in future clinical studies with the ECT formulation. The efficacy and safety of alisertib continue to be evaluated in a variety of solid and hematologic malignancies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in these studies, their supportive families, and the caring staff at all investigational sites. They would also like to acknowledge Catherine Crookes and Nadia Korfali of FireKite (an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc) for writing assistance in the development of this manuscript, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 RR024148, the Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) P30CA054174 to the Cancer Therapy and Research Center, University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, and the NIH CCSG award CA016672 to the MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

This research was supported by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Conflicts of interest

Gerald S. Falchook has received research funding and travel reimbursements from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Razelle Kurzrock has received research funding from Genentech, Merck Serono, Foundation Medicine, Pfizer, Guardant and Sequenom, as well as consultant fees from Sequenom, and has ownership interest in RScueRX, Inc. Lee S. Rosen has received research support from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Xiaofei Zhou, Karthik Venkatakrishnan, JungAh Jung, and Catherine Milch are employees of Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Devalingam Mahalingam, Jonathan W. Goldman, and John Sarantopoulos have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

G. S. Falchook and X. Zhou contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Barr AR, Gergely F. Aurora-A: the maker and breaker of spindle poles. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2987–2996. doi: 10.1242/jcs.013136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bar-Shira A, Pinthus JH, Rozovsky U, Goldstein M, Sellers WR, Yaron Y, et al. Multiple genes in human 20q13 chromosomal region are involved in an advanced prostate cancer xenograft. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6803–6807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff JR, Anderson L, Zhu Y, Mossie K, Ng L, Souza B, et al. A homologue of Drosophila aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J. 1998;17:3052–3065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dar AA, Zaika A, Piazuelo MB, Correa P, Koyama T, Belkhiri A, et al. Frequent overexpression of Aurora Kinase A in upper gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas correlates with potent antiapoptotic functions. Cancer. 2008;112:1688–1698. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gritsko TM, Coppola D, Paciga JE, Yang L, Sun M, Shelley SA, et al. Activation and overexpression of centrosome kinase BTAK/Aurora-A in human ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1420–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo IM, Monica V, Saviozzi S, Ceppi P, Bracco E, Papotti M, et al. Aurora kinase A expression is associated with lung cancer histological-subtypes and with tumor de-differentiation. J Transl Med. 2011;9:100. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park HS, Park WS, Bondaruk J, Tanaka N, Katayama H, Lee S, et al. Quantitation of Aurora kinase A gene copy number in urine sediments and bladder cancer detection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1401–1411. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiter R, Gais P, Jutting U, Steuer-Vogt MK, Pickhard A, Bink K, et al. Aurora kinase A messenger RNA overexpression is correlated with tumor progression and shortened survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5136–5141. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rojanala S, Han H, Munoz RM, Browne W, Nagle R, Von Hoff DD, et al. The mitotic serine threonine kinase, Aurora-2, is a potential target for drug development in human pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka T, Kimura M, Matsunaga K, Fukada D, Mori H, Okano Y. Centrosomal kinase AIK1 is overexpressed in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2041–2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand S, Penrhyn-Lowe S, Venkitaraman AR. AURORA-A amplification overrides the mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint, inducing resistance to Taxol. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:51–62. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meraldi P, Honda R, Nigg EA. Aurora-A overexpression reveals tetraploidization as a major route to centrosome amplification in p53−/− cells. EMBO J. 2002;21:483–492. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou H, Kuang J, Zhong L, Kuo WL, Gray JW, Sahin A, et al. Tumour amplified kinase STK15/BTAK induces centrosome amplification, aneuploidy and transformation. Nat Genet. 1998;20:189–193. doi: 10.1038/2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cervantes A, Elez E, Roda D, Ecsedy J, Macarulla T, Venkatakrishnan K, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study of MLN8237, an investigational, oral, selective aurora a kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4764–4774. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dees EC, Cohen RB, von Mehren M, Stinchcombe TE, Liu H, Venkatakrishnan K, et al. Phase I study of aurora A kinase inhibitor MLN8237 in advanced solid tumors: safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and bioavailability of two oral formulations. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4775–4784. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falchook G, Kurzrock R, Gouw L, Hong D, McGregor KA, Zhou X, et al. Investigational Aurora A kinase inhibitor MLN8237 (alisertib) as an enteric-coated tablet formulation in non-hematologic malignancies: phase 1 dose-escalation study. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32:1181–1187. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0121-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee P, Alvarez RH, Melichar B, Adenis A, Bennouna J, Schusterbauer C, et al. Phase I/II study of the investigational aurora A kinase (AAK) inhibitor MLN8237 (alisertib) in patients (pts) with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), small cell lung cancer (SCLC), breast cancer (BrC), head/neck cancer (H&N), and gastroesophageal (GE) adenocarcinoma: preliminary phase II results [abstract no. 3010]. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2012;30.

- 18.Charman WN, Porter CJ, Mithani S, Dressman JB. Physiochemical and physiological mechanisms for the effects of food on drug absorption: the role of lipids and pH. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86:269–282. doi: 10.1021/js960085v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Custodio JM, Wu CY, Benet LZ. Predicting drug disposition, absorption/elimination/transporter interplay and the role of food on drug absorption. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:717–733. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services, FDA and CDER. Guidance for industry: food-effect bioavailability and fed bioequivalence studies. December 2002. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/guidances/ucm126833.pdf. Accessed 26 Sept 2014.

- 21.Harris RZ, Jang GR, Tsunoda S. Dietary effects on drug metabolism and transport. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:1071–1088. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342130-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh BN, Malhotra BK. Effects of food on the clinical pharmacokinetics of anticancer agents: underlying mechanisms and implications for oral chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:1127–1156. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swaisland HC, Smith RP, Laight A, Kerr DJ, Ranson M, Wilder-Smith CH, et al. Single-dose clinical pharmacokinetic studies of gefitinib. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:1165–1177. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gleevec (imatinib mesylate) label – access data FDA. 2012. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/021588s035lbl.pdf. Accessed 26 Sept 2014.

- 26.Ling J, Fettner S, Lum BL, Riek M, Rakhit A. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of erlotinib, an orally active epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, in healthy individuals. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19:209–216. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3282f2d8e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tykerb (lapatinib) tablets—access data FDA. 2007. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022059s007lbl.pdf. Accessed 26 Sept 2014.

- 28.Sprycel (dasatinib) tablets label—access data FDA. 2010. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021986s7s8lbl.pdf. Accessed 26 Sept 2014.

- 29.Manfredi MG, Ecsedy JA, Chakravarty A, Silverman L, Zhang M, Hoar KM, et al. Characterization of Alisertib (MLN8237), an investigational small-molecule inhibitor of aurora A kinase using novel in vivo pharmacodynamic assays. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7614–7624. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang JJ, Li Y, Chakravarty A, Lu C, Xia CQ, Chen S, et al. Preclinical drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics, and prediction of human pharmacokinetics and efficacious dose of the investigational aurora A kinase inhibitor alisertib (MLN8237) Drug Metab Lett. 2014;7:96–104. doi: 10.2174/1872312807666131229122359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]