Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effects of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) infiltration in patients with lateral epicondylitis of the elbow, through analysis of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) and Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE) questionnaires.

Methods

Sixty patients with lateral epicondylitis of the elbow were prospectively randomized and evaluated after receiving infiltration of three milliliters of PRP, or 0.5% neocaine, or dexamethasone. For the scoring process, the patients were asked to fill out the DASH and PRTEE questionnaires on three occasions: on the day of infiltration and 90 and 180 days afterwards.

Results

Around 81.7% of the patients who underwent the treatment presented some improvement of the symptoms. The statistical tests showed that there was evidence that the cure rate was unrelated to the substance applied (p = 0.62). There was also intersection between the confidence intervals of each group, thus demonstrating that the proportions of patients whose symptoms improved were similar in all the groups.

Conclusion

At a significance level of 5%, there was no evidence that one treatment was more effective than another, when assessed using the DASH and PRTEE questionnaires.

Keywords: Platelet-rich plasma, Tendinopathy, Tennis elbow

Resumo

Objetivo

Avaliar os efeitos da infiltração do plasma rico em plaquetas (PRP) em pacientes com epicondilite lateral do cotovelo (ELC) pela análise dos questionários Deficiência do Braço, Ombro e Mão (Dash) e Avaliação do Paciente Portador do Cotovelo de Tenista (PRTEE).

Métodos

Foram randomizados e avaliados prospectivamente 60 pacientes, após receberem infiltrações de três mililitros de PRP, ou neocaína 0,5%, ou dexametasona. Para o processo de pontuação, os pacientes foram convidados a preencher os questionários Dash e PRTEE em três ocasiões: no dia da infiltração, 90 e 180 dias após.

Resultados

Dos pacientes submetidos ao tratamento, 81,7% apresentaram melhoria dos sintomas. Os testes estatísticos demonstraram que há evidências de que a taxa de cura não está relacionada com a substância aplicada (p = 0,62). Houve também interseção dos intervalos de confiança de cada grupo, com demonstração de que as proporções de pacientes cujos sintomas melhoraram foram semelhantes em todos os grupos.

Conclusão

Em um nível de significância de 5%, não houve evidência de que um tratamento foi mais eficaz do que a outro, quando avaliados pelos questionários Dash e PRTEE.

Palavras-chave: Plasma rico em plaquetas, Tendinopatia, Cotovelo do tenista

Introduction

Lateral epicondylitis of the elbow is a disease that mainly affects individuals who make repetitive movements with their wrists and/or fingers.1 The name “tennis elbow” does not correspond to the reality. Although around 40–50% of tennis players present this disease, especially those who have been practicing this sport for longer times,2 this group accounts for only 5% of the total number of individuals affected.3, 4 Although the term “lateral epicondylitis of the elbow” may also be inappropriate, given that this pathological condition does not involve a truly inflammatory process, but rather, a degenerative process,5, 6, 7, 8 it will be used in this study because it has been widely disseminated in the literature.

This injury predominantly involves the origin of the short radial extensor muscle of the carpus, in which microtears develop as a result of excessive and abnormal use, with formation of immature repair tissue.5

The symptoms of lateral epicondylitis of the elbow are generally self-limited and may vary in duration from a few weeks to months. However, in some cases, there is no spontaneous resolution of the symptoms, and this invariably leads to a chronic condition.9, 10 It also has to be borne in mind that lateral epicondylitis of the elbow is associated with long periods off work, which gives rise to high social security costs and substantial loss of professional productivity.11, 12, 13, 14

There is relatively little evidence based on good-quality clinical studies to support the various forms of treatment for lateral epicondylitis of the elbow that have been described in the literature. The treatment options range from relative rest in association with immobilization, physiotherapy, application of botulinum toxin, acupuncture, shockwave therapy, use of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroid injections and, most recently, use of platelet-rich plasma.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Surgical procedures are only recommended when the symptoms last for more than six months and/or if other non-surgical treatment options have failed.5, 17, 20

Given the high incidence of this disease, the expenditure that results from its treatment and, especially, the lack of consensus in the different databases available and in particular the Brazilian orthopedic databases, we proposed the present study. Its aim was to prospectively compare the results from three different options for treating lateral epicondylitis of the elbow, using the DASH and PRTEE questionnaires, which have recently been translated and validated for use in Portuguese.

Material and methods

Participants and study design

The protocol for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Beings, under no. 453/12. All the patients or their guardians agreed to participate in the study through signing a free and informed consent statement, after having been given detailed information about the content and form of the study.

The sample size was determined before starting the study. The α and β risks (respectively 5% and 20%) and the variability of the variables (p1 = 0.2 and p2 = 0.63) were taken into account, and a minimum number of 20 participants per group was thus determined.

Between February 2012 and February 2014, 72 consecutive patients with lateral epicondylitis of the elbow were selected for the study. The inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 18 years and positive findings from two of the following clinical tests: Cozen, Mill, Gardner and Maudsley. The following patients were excluded: those who had undergone some form of previous treatment in the elbow region; those who presented other diseases in the upper limbs (such as posterior interosseous nerve syndrome and/or carpal tunnel syndrome): patients with systemic diseases (such as diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism and/or rheumatoid arthritis); pregnant patients; and lastly, patients using contraceptive drugs.10, 11 Ultrasound examinations were performed only to document the cases and form an image database. Through applying the criteria, 60 patients were included in this study.

Instruments

The instruments most used for measuring the functionality and degree of impairment of patients’ elbow region are the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire and the Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE). Both of these instruments have been validated for use in Portuguese. The DASH questionnaire measures the incapacity of the upper limb as a single unit, always from the patient's perspective.12, 14, 15 On the other hand, the PRTEE was developed solely to evaluate lateral epicondylitis of the elbow.

Both questionnaires were applied to all the patients at three different times: on the day of infiltration (DASH-0 and PRTEE-0), 90 days afterwards (DASH-90 and PRTEE-90) and 180 days afterwards (DASH-180 and PRTEE-180).

Blinding and randomization process

With the aim of ensuring greater reliability for the results and greater investigative power for the study, it was decided to institute a process of triple blinding.

The randomization process consisted of the method of sealed opaque envelopes.21, 22 The allocation group was stated inside each envelope: group A (n = 20; 5% neocaine), group B (n = 20; dexamethasone) and group C (n = 20; PRP).

Preparation and application of platelet-rich plasma

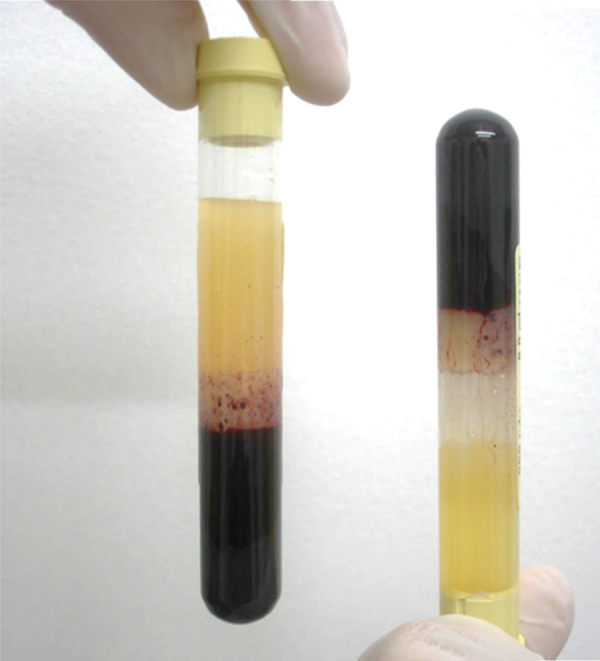

The PRP used in this study was obtained as recommended by Vendramin et al.23 60 ml of blood that had previously been taken from each patient was divided between six 10 ml tubes that contained sodium citrate. These tubes were then subjected to two cycles of centrifugation, under forces of 400 g and 800 g, for 10 min.

Two thirds of the original volume (platelet-poor plasma) was discarded in this method. Only one third of the original blood sample consisted of PRP (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Preparation of the platelet-rich plasma.

Finger pressure was applied locally to the patients so that they could identify the region of greatest pain (Fig. 2). Before placement of sterile ocular fields, asepsis and antisepsis procedures were performed using chlorhexidine. The patients in group A then underwent local infiltration of 3 ml of 0.5% neocaine; group B received infiltration of 3 ml of dexamethasone acetate; and group C received infiltration of 3 ml of platelet-rich plasma. All the syringes were covered with a double layer of aluminum foil, for the infiltration procedure, by a person who was unconnected to the study.

Fig. 2.

Identification of the infiltration site (circled) and the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN).

Statistical analysis

To perform the statistical calculations, the software used comprised SigmaStat® 3.5 (Systat Software Inc., 2006) and Minitab® version 15 (Minitab Inc., 2007), The significance level was taken to be 5% (p < 0.05).

The variables were analyzed by means of descriptive, parametric and nonparametric statistical tests in a fully randomized model. The parametric option was used when the variable presented Gaussian behavior (Student's t test and ANOVA). If the distribution was non-Gaussian, the nonparametric option was indicated (Mann–Whitney U test and Fisher's exact test). The mean values, standard deviations, medians, frequencies, percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated (α = 5%).

Results

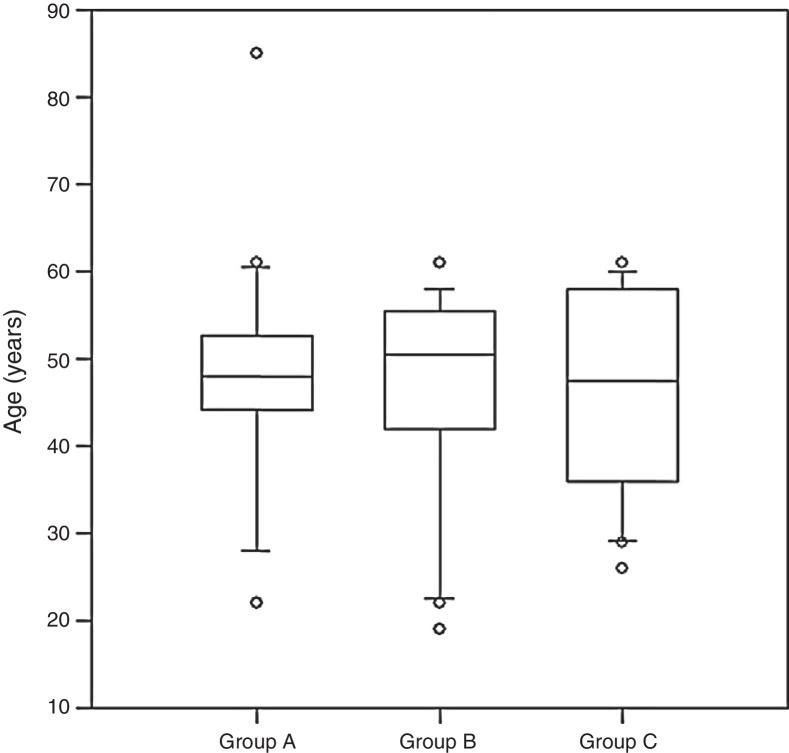

The ages in group A ranged from 22 to 85 years (mean: 47.9; 95% CI: 42.2–53.6 years); in group B the range was from 19 to 61 years (mean: 46.2; 95% CI: 41–51.5 years); and in group C it was from 26 to 61 years (mean: 46.6; 95% CI: 41.6–51.6 years) (Kruskal–Wallis; p = 0.99) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Ages of the patients in the groups (Kruskal–Wallis; p = 0.99).

In all three groups, the score in the DASH-90 questionnaire was lower than the score in DASH-0, although the maximum values found in DASH-90 were greater than those in DASH-0. This discrepancy can be explained by the scores attributed to a single patient, which reached 75.8 and 80.8 points in the DASH-0 and DASH-90 questionnaires, respectively. Furthermore, another participant had a lower score in DASH-0 (34.2) than in DASH-90 (37.5). For the same reasons, slightly higher standard error values can be seen in DASH-90 than in DASH-0 (Table 1, Table 2). The values from the DASH-180 questionnaires were taken to be zero in all three groups.

Table 1.

Scores from the DASH-0 questionnaires in the three groups.

| Group | Minimum score | Maximum score | Median | Mean | Standard error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 25.0 | 73.3 | 49.2 | 49.7 | 3.0 |

| B | 15.0 | 75.8 | 40.4 | 44.3 | 4.4 |

| C | 22.5 | 82.5 | 40.8 | 45.7 | 3.8 |

Table 2.

Scores from the DASH-90 questionnaires in the three groups.

| Group | Minimum score | Maximum score | Median | Mean | Standard error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.8 | 71.7 | 10.2 | 16.6 | 3.8 |

| B | 0.0 | 80.8 | 12.1 | 19.8 | 4.9 |

| C | 1.7 | 79.2 | 5.0 | 10.7 | 4.0 |

In relation to the PRTEE questionnaire, it was noted that in all three groups, the scores relating to PRTEE-90 were lower than those of PRTEE-0. However, the maximum scores in groups B and C were higher in PRTEE-90 than in PRTEE-0. This discrepancy can be explained by the scores of a single participant who reached 65.5 points (PRTEE-0) and 85.0 points (PRTEE-90), both in group B; and another patient who reached scores of 83.0 (PRTEE-0) and 91.5 (PRTEE-90), both in group C. It is also important to note that another five individuals presented higher scores in PRTEE-90 (two in group A, two in group B and one in group C) (Table 3, Table 4). The values from the PRTEE-180 questionnaires were taken to be zero in all three groups.

Table 3.

Scores from the PRTEE-0 questionnaires in the three groups.

| Group | Minimum score | Maximum score | Median | Mean | Standard error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 18.0 | 82.5 | 52.5 | 51.7 | 4.4 |

| B | 17.0 | 83.5 | 35.8 | 42.9 | 4.3 |

| C | 24.5 | 88.5 | 37.0 | 47.1 | 4.9 |

Table 4.

Scores from the PRTEE-90 questionnaires in the three groups.

| Group | Minimum score | Maximum score | Median | Mean | Standard error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.5 | 80.0 | 9.5 | 15.5 | 3.9 |

| B | 0.0 | 85.0 | 12.8 | 21.8 | 5.5 |

| C | 0.5 | 91.5 | 6.5 | 13.0 | 4.7 |

Table 5 shows the absolute quantity (n) and proportion (%) of the patients who reported achieving some improvement in symptoms, as demonstrated by a difference greater than or equal to 15 points (binomial distribution) between the DASH-0 and DASH-90 questionnaires. The values from the PRTEE-180 questionnaires were taken to be zero in all three groups.

Table 5.

Difference between the DASH-0 and DASH-90 questionnaires (scores ≥ 15).

| Group | n | % | Standard error | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 20 | 90.0 | 6.8 | [68.3–98.8] |

| B | 20 | 65.0 | 10.9 | [40.8–94.6] |

| C | 20 | 90.0 | 6.8 | [68.3–98.8] |

Overall, 81.7% of the patients had some improvement in their symptoms. In groups A and C, there were reports of improvement in 90% of the cases and in group B the proportion was 65% (p = 0.62). IN other words, there was evidence that the proportion of care was unrelated to the substance used, at the significance level of 5%. Moreover, the confidence intervals correlated between the groups, which shows that the proportion of improvement of symptoms was the same in the three groups.

In order to confirm the results from the DASH questionnaires, the proportions of improvement were matches and compared using Student's t test. For the pairings A/B and B/C, the proportions were statistically the same (p = 0.56), and also in the pairing A/C (p = 0.41).

Improvement of the symptoms in the PRTEE questionnaire was defined as a difference in scores between the questionnaires greater than or equal to 7 points. In this study, 90% of the participants in groups A and C reported achieving improvements, as did 85% in group B. The test of independence between the groups did not present statistical significance (p = 0.85) (Table 6). In the same way as in the DASH questionnaire, there was evidence that the proportion that achieved a cure did not depend on the substance used, at the significance level of 5%.

Table 6.

Difference between the PRTEE-0 and PRTEE-90 questionnaires (scores ≥ 7).

| Group | n | % | Standard error | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 20 | 90.0 | 6.8 | [68.3–98.8] |

| B | 20 | 85.0 | 8.2 | [62.1–96.8] |

| C | 20 | 90.0 | 6.9 | [68.3–98.8] |

Once again, in order to confirm the results from the PRTEE questionnaires, the proportions of improvement were matched and compared using Student's t test. In relation to the pairings A/B, B/C and A/C, the proportions were statistically the same (p = 0.66).

Table 7 shows the results from the kappa test, for interobserver agreement relating to the questionnaires that were applied. It could be seen that there was substantial agreement between the two questionnaires (p = 0.6). In relation to the internal concordance of the questionnaires, Cronbach's alpha test showed that there was consistency between the questionnaires (p = 0.8).

Table 7.

Kappa test for intraobserver analysis on improvement of symptoms (DASH and PRTEE).

| PRTEE |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without improvement | With improvement | Total | |

| Dash | |||

| Without improvement | 10.0 | 8.3 | 18.3 |

| With improvement | 1.7 | 80.0 | 81.7 |

| Total | 11.7 | 88.3 | 100 |

Discussion

Visual analogue scales (VAS) for assessing pain are the most commonly used method for measuring painful conditions because they are quickly and easily applied. However, using VAS presents practical limitations within clinical scenarios, given that most patients report that they have difficulty in translating the physical intensity of their pain into a scale in millimeters.20

Several mechanisms of action for PRP have been described in the literature. In principle, these explain the clinical improvement of the participants in this study: the local hemostatic action of the substance during the postoperative period, along with its influence on osteogenesis and soft-tissue healing, especially muscle healing.11 There is also the hypothesis that autologous blood injections have a direct influence on the cascade of inflammation and cause an early start to recovery of the degenerated tissue.10

Local infiltration of corticosteroids, which is considered by many surgeons to be the best option for treating lateral epicondylitis of the elbow, has been questioned. Some authors have suggested that the improvement observed in these patients only has partial and temporary efficacy.16

Although some authors12 have reported that application of PRP is the most promising method for treating lateral epicondylitis of the elbow, the present study produced discouraging results from prospective analysis on two different validated assessment scales, in relation to the increasingly fashionable use of PRP. There was no statistically significant difference between the forms of treatment over the 180 days of follow-up of the patients (Table 5, Table 6). Moreover, the improvement in symptoms seen over the course of the study period was shown to be statistically the same for the three substances (Table 7).

However, it is important to emphasize that when more than two peritendinous infiltrations are applied, some undesirable side effects such as local necrosis, tissue atrophy and tendon tearing may occur.1, 8, 13 These may be the real reason why medical professionals prefer to apply PRP, rather than corticosteroids.

Conclusion

This study did not supply any statistical evidence that PRP might provide better results than treatment with corticosteroids or local anesthetic, in treating lateral epicondylitis of the elbow.

On the other hand, there was statistical agreement between the DASH and PRTEE scales. The Portuguese-language versions of both questionnaires were shown to be effective for evaluating the evolution of the disease.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Research Support Foundation of the State of São Paulo (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, FAPESP), through procedural nos. 2012/19254-0 and 2012/19291-2, for its support in developing this study.

Footnotes

Work developed in the Department of Orthopedics, Traumatology and Sports and Exercise Medicine, Faculdade de Medicina de Marília (FAMEMA), Marília, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Mishra A., Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1774–1778. doi: 10.1177/0363546506288850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gruchow H.W., Pelletier D. An epidemiologic study of tennis elbow: incidence, recurrence, and effectiveness of prevention strategies. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7(4):234–238. doi: 10.1177/036354657900700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assendelft W.J.J., Hay E.M., Adshead R., Bouter L.M. Corticosteroid injections for lateral epicondylitis: a systematic overview. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46(405):209–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lech O., Piluski P.C.F., Severo A.L. Epicondilite lateral do cotovelo. Rev Bras Ortop. 2003;38(8):421–436. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nirschl R.P., Pettrone F.A. Tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61(6):832–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regan W., Wold L.E., Coonrad R., Morrey B.F. Microscopic histopathology of chronic refractory lateral epicondyliitis. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20(6):746–749. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geoffroy P., Yaffe M.J., Rohan I. Diagnosing and treating lateral epicondylitis. Can Fam Physician. 1994;40:73–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fredberg U., Stengaard-Pedersen K. Chronic tendinopathy tissue pathology, pain mechanisms, and etiology with a special focus on inflammation. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18(1):3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiri R., Viikari-Juntura E. Lateral and medial epicondylitis: role of occupational factors. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(1):43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thanasas C., Papadimitriou G., Charalambidis C., Paraskevopoulos I., Papanikolaou A. Platelet rich plasma versus autologous whole blood for the treatment of chronic lateral elbow epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2130–2134. doi: 10.1177/0363546511417113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker-Bone K., Palmer K.T., Reading I.C., Coggon D., Cooper C. Occupation and epicondylitis: a population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxf) 2012;51(2):305–310. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchbinder R., Richards B.L. Is lateral epicondylitis a new indication for botulinum toxin? Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182(8):749–750. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rempel D.M., Harrison R.J., Barnhart S. Disorders of the upper extremity. J Am Med Assoc. 1992;267(6):838–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverstein B., Adams D. SHARP Program, Washington State Department of Labor and Industries; Olympia, Washington: 2007. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, back, and upper extremity in Washington State, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson G.W., Cadwallader K., Scheffel S.B., Epperly T.D. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Am Fam Phys. 2007;76(6):843–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smidt N., van der Windt D.A., Assendelft W.J., Devillé W.L., Korthals-de Bos I.B., Bouter L.M. Corticosteroid injection, physiotherapy, or wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9307):657–662. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strujis P.A.A., Bos I.B.C.K., van Tulder M.W., van Dijk C.N., Bouter L.M., Assendelft W.J.J. Cost effectiveness of brace, physiotherapy, or both for treatment of tennis elbow. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(7):637–643. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.026187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olaussen M., Holmedal Ø., Lindbaek M., Brage S. Physiotherapy alone or in combination with corticosteroid injection for acute lateral epicondylitis in general practice: a protocol for a randomised, placebo-controlled-study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galvin R., Callaghan C., Chan W.S., Dimitrov B.D., Fahey T. Injection of botulinum toxin for treatment of chronic lateral epicondylitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Athritis Rheum. 2011;40(6):585–587. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong S.M., Hui A.C.F., Tong P., Yu E., Wong L.K.S. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with botulinum toxin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(11):793–797. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-11-200512060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doig G.S., Simpson F. Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researches. J Crit Care. 2005;20(2):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altman D.G., Schulz K.F. Statistics notes: concealing treatment allocation in randomised trials. BMJ. 2001;323(7310):446–447. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7310.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vendramin F.S., Franco D., Franco T.R. Método de obtenção do gel de plasma rico em plaquetas autólogo. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2009;24(2):212–218. [Google Scholar]