Abstract

Background

Remifentanil is known to cause bradycardia and hypotension. We aimed to characterize the haemodynamic profile of remifentanil during sevoflurane anaesthesia in children with or without atropine.

Methods

Forty children who required elective surgery received inhalational induction of anaesthesia using 8% sevoflurane. They were allocated randomly to receive either atropine, 20 mg kg−1 (atropine group) or Ringer’s lactate (control group) after 10 min of steady-state 1 MAC sevoflurane anaesthesia (baseline). Three minutes later (T0), all children received remifentanil 1 mg kg−1 injected over a 60 s period, followed by an infusion of 0.25 mg kg−1 min−1 for 10 min then 0.5 mg kg−1 min−1 for 10 min. Haemodynamic variables and echocardiographic data were determined at baseline, T0, T5, T10, T15 and T20 min.

Results

Remifentanil caused a significant decrease in heart rate compared with the T0 value, which was greater at T20 than T10 in the two groups: however, the values at T10 and T20 were not significantly different from baseline in the atropine group. In comparison with T0, there was a significant fall in blood pressure in the two groups. Remifentanil caused a significant decrease in the cardiac index with or without atropine. Remifentanil did not cause variation in stroke volume (SV). In both groups, a significant increase in systemic vascular resistance occurred after administration of remifentanil. Contractility decreased significantly in the two groups, but this decrease remained moderate (between −2 and +2 SD).

Conclusion

Remifentanil produced a fall in blood pressure and cardiac index, mainly as a result of a fall in heart rate. Although atropine was able to reduce the fall in heart rate, it did not completely prevent the reduction in cardiac index.

Keywords: Adjuvants, Anesthesia; Adolescent; Depression, Chemical; Echocardiography, Doppler; Female; Heart Rate; Hemodynami; Anesthetics, Combined; Anesthetics, Inhalation; Anesthetics, Intravenous; Atropine; Blood Pressure; Cardiac Output; Child; Child, Preschool

Remifentanil hydrochloride is a short-acting opioid of the phenylpiperidine class which is widely used in adult general anaesthesia1 and has been used in paediatric anaesthesia.2 3 A preliminary pharmacokinetic study in children aged 0–18 yr suggested a pharmacokinetic profile similar to that of adults: a small volume of distribution, a rapid distribution phase, a half-life with mean of 3.4–5.7 min and extremely rapid elimination.3

Remifentanil is known to cause bradycardia and hypotension3–5 but the mechanisms are unclear. The potential for inducing these side-effects has been one of the reasons for the relatively infrequent use of remifentanil in children.

The aim of this study was to characterize the haemodynamic profile of remifentanil using non-invasive echocardiographic data6 7 during sevoflurane anaesthesia in children with and without atropine.

Materials and methods

Forty children aged 0.8–13 yr, classified as ASA physical status I or II and who required elective surgery, were studied prospectively after approval of the protocol by our Institutional Human Studies Committee. Informed written parental consent was obtained. Patients with cardiac and neurological disease were excluded. The children were not allowed to eat or drink for 6 h before the operation and were premedicated 30 min before induction of anaesthesia with rectal midazolam 0.3 mg kg−1.

Anaesthesia was induced by inhalation of sevoflurane 8% in oxygen 100% through an open circuit in all patients. After placement of an i.v. line, the trachea was intubated and the lungs were ventilated to maintain normocapnia. Sevoflurane was then reduced to 1 MAC corrected for age for at least 10 min to achieve steady state. At this point (baseline), children were assigned randomly to receive i.v. (in 4 ml) either atropine 20 μg kg−1 (atropine group) or Ringer’s lactate (control group). Three minutes later (T0), all children received a bolus of remifentanil 1 μg kg−1 injected over a 60 s period followed by an infusion of remifentanil 0.25 μg kg−1 min−1 for 10 min then 0.5 μg kg−1 min−1 for 10 min. At the end of the 20 min the study was finished and surgery could start. No neuromuscular blocking agents were administered.

During the study the heart rate, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) and end-tidal carbon dioxide ( ) were monitored continuously. Non-invasive blood pressure (mm Hg) was measured every minute using an automated blood pressure cuff with an appropriate cuff size in relation to the size of the child’s arm. Bradycardia was defined as greater than 20% decrease in heart rate. The following haemodynamic variables were recorded at baseline, T0, T5, T10, T15 and T20 min: heart rate, mean blood pressure (MBP), continuous Doppler, and 2D transthoracic echocardiographic data (Sonos 1000; Hewlett-Packard, Andover, MA, SA). The echocardiographic data obtained in each patient included aortic diameter and shortening fraction (SF). In the long-axis view of the left ventricular outflow tract (using the 2D mode), the end-systolic internal aortic diameter (Dao) was measured, at the annulus, and the aortic sectional area (SaAo) was calculated as (SaAo=π(Dao)2/4). The SF was measured by M mode from the parasternal long-axis view of the left ventricle at the junction of mitral valve leaflets and the papillary muscle. The left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVDD) was measured at the point of maximum diameter, and the left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVSD) was measured at the point of peak upward deflection of the posterior wall. The posterior wall thickness (Pwes) was measured at end-systole. The SF was calculated as (LVDD–LVSD)/LVDD and expressed as a percentage. The rate-corrected velocity of circumferential fibre shortening (VCFc) was calculated using the formula VCFc=SF/rate-corrected ejection time. The rate-corrected ejection time was ejection time divided by the square root of the R–R interval (to correct to a heart rate of 60 beats min−1). The left ventricular end-systolic wall stress (ESWS) was calculated using the formula: ESWS=(1.35×MBP×LVSD)/[(1+Pwes/LVSD)×(Pwes)×4].8

Continuous Doppler readings were used to measure the flow in the ascending aorta from the suprasternal view of the heart. The audio signal intensity was used to confirm positioning for maximal aortic blood flow velocities. Because the angle between the estimated direction of blood flow and the Doppler beam was ≤15° or less, no angle correction of the Doppler signal was made. The mean aortic flow velocity (Vao) was calculated using the software of the ultrasound system as average velocity multiplied by flow period. The average of three consecutive flow velocity integrals was taken. The cardiac index (CI) was calculated from the volumetric equation: CI (ml kg−1 min−1)=Vao (cm/s)×SaAo (cm2)×60/body weight (kg). The systemic vascular resistance (SVR) was evaluated as the quotient of the mean blood pressure and CI without measurement of right atrial pressure.

The VCFc–ESWS relation or SF–ESWS relation can be used to determine contractility independently of loading conditions. However, SF, VCFc and ESWS were age- and body surface area-dependent. As described by Colan and colleagues, the Z score rather than the absolute value was used to normalize these calculations, with age- and growth-related means taken from values established for healthy children or infants.9 The stress–velocity index for each child was determined relative to the distribution of this index in children at the steady state with sevoflurane without remifentanil and calculated as a normal deviate (Z score). The stress velocity index was calculated as (X1–M)/SD, where X1 is the measured VCFc, M is mean VCFc calculated for the measured ESWS, and SD is the standard deviation of the regression group stress–velocity index. The stress–shortening index (SSI) was correspondingly quantified as the normal deviate of fractional shortening for the given ESWS, obtained in a manner analogous to that described for the stress–velocity index. The normal value of the Z score was between −2 and +2.

All echo measurements were obtained by the same observer, who was not aware of the study hypothesis or the design details.

Statistical analysis was done using non-parametric tests. The analysis of the overall evolution of the variables between the two groups was carried out with Friedman’s test. Comparisons between groups were made with the Mann–Whitney test and comparisons within groups with the Wilcoxon matched test. A probability value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Values are expressed as median (range).

Results

The clinical characteristics of the children are shown in Table 1. The groups were similar with regard to age, weight, sex, heart rate, mean blood pressure and echographic haemodynamic data at baseline (Table 1, Figs 1–3).

Table 1.

Children’s clinical characteristics in groups receiving either Ringer lactate (control) or atropine (AT) just before infusion of remifentanil. MBP=mean blood pressure; E′SEVO=end-tidal sevoflurane concentration

| Age (months) Median (range) |

Weight (kg) Median (range) |

Sex | MBP (mm Hg) Median (range) |

E′SEVO (%) Median (range) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atropine | 50 (8–162) | 16.5 (7.7–49) | M=14 F=6 |

60.5 (50–75) | 2.6 (2.3–2.9) |

| Control | 51 (11–134) | 17 (8.3–33) | M=14 F=6 |

61 (53–80) | 2.5 (2.3–2.8) |

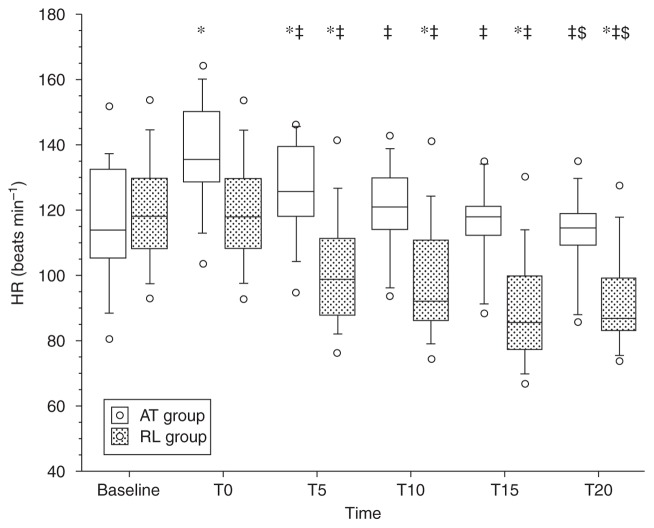

Fig. 1.

Heart rate (beats min−1) values under remifentanil compared with 1 MAC sevoflurane steady-state values (baseline). T0=time after injection of atropine (AT) or Ringer (RL); time (min) 5 and 10 under remifentanil at 0.25 μg kg−1 min−1; time 15 and 20 under remifentanil at 0.5 μg kg−1 min−1. Vs baseline, *P<0.05; vs T0, ‡P<0.05; vs T10, $P<0.05. Open circles correspond to minimum and maximum values.

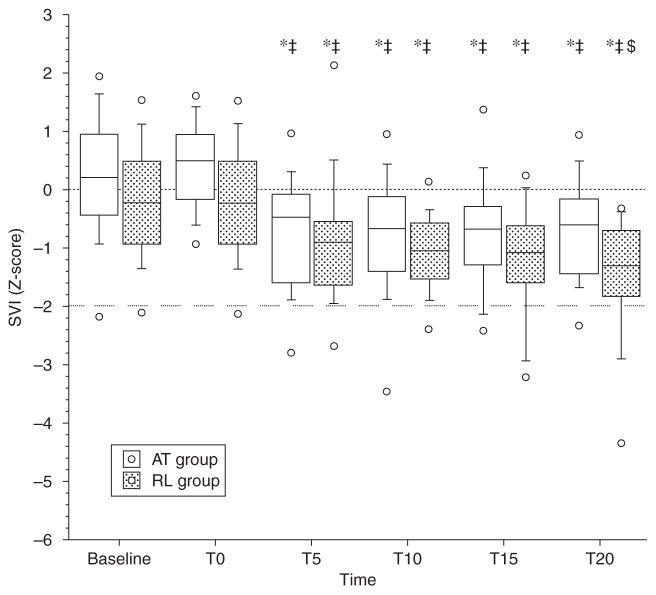

Fig. 3.

Contractility values (stress–velocity index, SVI) under remifentanil compared with 1 MAC sevoflurane steady-state values (baseline). T0=time after injection of atropine (AT) or Ringer (RL); time (min) 5 and 10 under remifentanil at 0.25 μg kg−1 min−1; time 15 and 20 under remifentanil at 0.5 μg kg−1 min−1. Vs baseline, *P<0.05; vs T0, ‡P<0.05; vs T10, $P<0.05. Open circles correspond to minimum and maximum values.

In comparison with baseline, remifentanil caused a significant decrease in heart rate in the control group at T10 and T20 (Fig. 1). In comparison with baseline, in the atropine group remifentanil did not cause a decrease in heart rate at T10 and T20, and heart rate returned to the baseline value at T20. In comparison with T0 (after pretreatment), remifentanil caused a significant decrease in heart rate in all patients with or without atropine. These decreases were greater at T20 than T10 (Fig. 1). There were significantly more children in the control group than in the atropine group who experienced a fall of 20% in the heart rate at T10 (45 vs 0% respectively) and T20 (75 vs 5%). Administration of remifentanil was associated with a significant reduction in MBP compared with baseline and after pretreatment (T0) in the two groups at T10 and T20 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage changes (Δ) in haemodynamic values in comparison with baseline value at 1 MAC end-tidal sevoflurane steady-state. Vs baseline

| Δ (%) groups | T0

|

T10

|

T20

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | |

| Δ HR | ||||||

| Atropine | +20* | (−2, 43) | +7 | (−16, 32) | 0‡ | (−23, 31) |

| Control | 0 | (−1, 2) | 0* | (−32, −8) | −26*‡ | (−31, −13) |

| Δ MBP | ||||||

| Atropine | +16 | (−9, 21) | −8* | (−38, 9) | −11* | (−31, 26) |

| Control | 0 | (−4, 3) | −12* | (−29, 7) | −15*‡ | (−38, 2) |

| Δ SVR | ||||||

| Atropine | +2 | (−22, 33) | 0 | (−21, 15) | +8*‡ | (−14, 50) |

| Control | −1 | (−6, 7) | +12* | (−7, 44) | +15*‡ | (−14, 52) |

| Δ SV | ||||||

| Atropine | −13* | (−28, 1) | −11* | (−30, −3) | −18* | (−29, 0) |

| Control | 0 | (−3, 5) | −4 | (−24, 19) | 3 | (−27, 18) |

P<0.05; vs T10,

P<0.05.

SV=stroke volume; SVR=systemic vascular resistance; HR=heart rate; MBP=mean blood pressure. T0=after pretreatment, before remifentanil; T10=0.25 μg kg−1 min−1; T20=0.5 μg kg−1 min−1

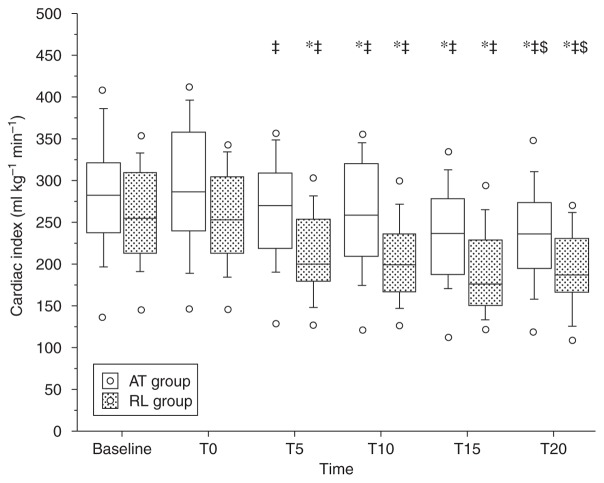

The CI decreased significantly in the two groups after administration of remifentanil, but this decrease was less in the atropine group than in the control group (Fig. 2). The reduction in CI was greater at T20 than T10 in both groups. There were significantly more children in the control group than in the atropine group who experienced a fall of 20% in CI at T10 (50 vs 10% respectively) and T20 (70 vs 25%). In the atropine group, the stroke volume (SV) decreased soon after the atropine was injected and before the start of the remifentanil infusion (Table 2). This fall in SV persisted throughout the study period. There was no significant variation in SV in both groups at all times compared with T0. The SVR increased significantly compared with baseline and T0 after infusion of remifentanil in the control group, but an increase was apparent in the atropine group only at T20 (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Cardiac index values under remifentanil compared with 1 MAC sevoflurane steady-state values (baseline). T0=time after injection of atropine (AT) or Ringer (RL); time (min) 5 and 10 under remifentanil at 0.25 μg kg−1 min−1; time 15 and 20 under remifentanil at 0.5 μg kg−1 min−1. Vs baseline, *P<0.05; vs T0, ‡P<0.05; vs T10, $P<0.05. Open circles correspond to minimum and maximum values.

Administration of atropine did not change the stress–velocity index or the SSI. However, after administration of remifentanil the stress–velocity index and the SSI decreased significantly in both groups compared with baseline and T0, with no significant difference between the two groups: this decrease remained, however, between −2 and +2 SD of the baseline values (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The decrease in blood pressure induced by remifentanil in children during sevoflurane anaesthesia was mainly dependent on a fall in CI. Although atropine prevented a fall in heart rate compared with baseline, this reduced, but did not prevent, the fall in CI and had minimal effect on the fall in mean blood pressure.

Many authors have shown that remifentanil can induce a decrease in heart rate in adult as well as in paediatric patients.5 10–17 Indeed, Klemola and colleagues reported a significant fall of 6–9% in heart rate when remifentanil was administered at induction of anaesthesia to children who had been pretreated with atropine before induction.14 The cardiovascular side-effects of remifentanil appear to be similar to those of other opioids (such as fentanyl and alfentanil), although the degree of bradycardia with remifentanil seems greater than with the other opioids. In our study, remifentanil caused a progressive decrease in heart rate during the first level of infusion (0.25 μg kg−1 min−1) and then a further reduction during the second level of infusion (0.5 μg kg−1 min−1), suggesting a dose-dependent effect of remifentanil on heart rate. In a similar way, Wee and colleagues found a higher incidence of bradycardia and hypotension when remifentanil was given to infants with a 1 μg kg−1 min−1 loading dose compared with an initial infusion of 0.25 μg kg−1 min−1.10 These results could explain the high proportion of children with bradycardia in our study who had not received atropine pretreatment.

Ross and colleagues showed a 17% incidence of remifentanil-related hypotension in a paediatric study in which atropine was given at the discretion of the anaesthetist.3 Similarly, Klemola and colleagues reported a decrease in MBP of 11–13% after anaesthetic induction with remifentanil.14 Our results are consistent with these.

In our study, the fall in MBP resulted from a dose-dependent fall in CI. Although the fall in CI was greater in the control group, this was offset by a greater increase in SVR compared with the atropine group, so that the fall in MBP was similar in the two groups. In the control group, and in contrast to studies in adults,11 12 remifentanil had no effect on the stroke volume, while the reduction in SV in the atropine group was apparent before the administration of remifentanil. In the control patients, therefore, the reduction in heart rate can largely explain the reduced CI caused by remifentanil. Administration of atropine had no significant effect on CI before remifentanil was given because the increased heart rate was offset by a fall in SV. The addition of remifentanil reversed the tachycardia but had no effect on the SV, thereby reducing the CI. Thus, irrespective of pretreatment with atropine, remifentanil reduces the CI below baseline values by causing a reduction in the absolute (rather than relative to baseline) value of the heart rate.

We have not been able to find any previous reports of atropine causing a reduction in SV in children. The reduction in SV could be due to a loading defect secondary to tachycardia. However, at T20 in the atropine group the SV remained impaired, whereas the heart rate had returned to baseline. As atropine did not significantly change the SVR at T0 in the atropine group, the effect of atropine on SV could be attributed to a preload decrease, i.e. a vasodilator effect. This finding could explain the smaller increase in SVR in the atropine group during the remifentanil infusion.

Myocardial contractility is difficult to quantify in clinical practice. Using echocardiographic measurements, Colan and colleagues reported the possibility of determining an estimate of myocardial contractility in a non-invasive manner and independently of loading conditions in children as well as in adults.9 This method has already been used successfully in paediatric anaesthesia to compare the effects of different anaesthetics.18–20 In the present study, the myocardial contractility index represented by SSI and the stress–velocity index appeared to be moderately reduced in the two groups, remaining between −2 and +2 SD. This allows us to establish that the effect of remifentanil on myocardial contractility is probably moderate in healthy children.

No severe adverse effects occurred in our study with remifentanil. We intentionally used high infusion rates of remifentanil to allow us to analyse the haemodynamic effects and safety of remifentanil in children. The same infusion doses have already been used safely in adults.21 Taking into account the doses of remifentanil used, only half of the children in the control group experienced a 20% drop of CI, compared with 10% in the atropine group. All episodes of hypotension (decrease from baseline >20%) and bradycardia resolved spontaneously without pharmacological intervention when the rate of remifentanil infusion was decreased.

Thus, during sevoflurane anaesthesia in children, remifentanil decreased mean blood pressure and CI mainly because of a decrease in heart rate. Although pretreatment with atropine was able to limit the effect of remifentanil on heart rate, its potential beneficial effects on blood pressure and CI appeared to be less. The specific effect of atropine on SV in children during sevoflurane anaesthesia requires further investigation.

References

- 1.Egan TD, Lemmens HJ, Fiset P, et al. Remifentanil versus alfentanil: comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in healthy adult male volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:821–33. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prys-Roberts C, Lerman J, Murat I, et al. Comparison of remifentanil versus regional anaesthesia in children anaesthetised with isoflurane/nitrous oxide. International Remifentanil Paediatric Anaesthesia Study group. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:870–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross AK, Davis PJ, Dear Gd GL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of remifentanil in anesthetized pediatric patients undergoing elective surgery or diagnostic procedures. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1393–401. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogue CW, Jr, Bowdle TA, O’Leary C, et al. A multicenter evaluation of total intravenous anesthesia with remifentanil and propofol for elective inpatient surgery. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:279–85. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199608000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeSouza G, Lewis MC, TerRiet MF. Severe bradycardia after remifentanil. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1019–20. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardin JM, Dabestani A, Matin K, Allfie A, Russell D. Reproducibility of Doppler aortic blood flow measurements: studies on intraobserver, interobserver and day-to-day variability in normal subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:1092–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(84)80150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanseus K, Bjorkhem G, Lundstrom NR. Cardiac function in healthy infants and children: Doppler echocardiographic evaluation. Pediatr Cardiol. 1994;15:211–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00795729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowland DG, Gutgesell HP. Use of mean arterial pressure for noninvasive determination of left ventricular end-systolic wall stress in infants and children. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:98–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colan SD, Parness IA, Spevak PJ, Sanders SP. Developmental modulation of myocardial mechanics: age- and growth-related alterations in afterload and contractility. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:619–29. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wee LH, Moriarty A, Cranston A, Bagshaw O. Remifentanil infusion for major abdominal surgery in small infants. Paediatr Anaesth. 1999;9:415–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1999.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott P, O’Hare R, Bill KM, Phillips AS, Gibson FM, Mirakhur RK. Severe cardiovascular depression with remifentanil. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:58–61. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kazmaier S, Hanekop GG, Buhre W, et al. Myocardial consequences of remifentanil in patients with coronary artery disease. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:578–83. doi: 10.1093/bja/84.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens JB, Wheatley L. Tracheal intubation in ambulatory surgery patients: using remifentanil and propofol without muscle relaxants. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:45–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199801000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klemola UM, Hiller A. Tracheal intubation after induction of anesthesia in children with propofol–remifentanil or propofol–rocuronium. Can J Anaesth. 2000;47:854–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03019664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friesen RH, Veit AS, Archibald DJ, Campanini RS. A comparison of remifentanil and fentanyl for fast track paediatric cardiac anaesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:122–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis PJ, Lerman J, Suresh S, et al. A randomized multicenter study of remifentanil compared with alfentanil, isoflurane, or propofol in anesthetized pediatric patients undergoing elective strabismus surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:982–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199705000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roulleau P, Gall O, Desjeux L, Dagher C, Murat I. Remifentanil infusion for cleft palate surgery in young infants. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:701–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holzman RS, Van der Velde ME, Kaus SJ, et al. Sevoflurane depresses myocardial contractility less than halothane during induction of anesthesia in children. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:1260–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wodey E, Pladys P, Copin C, et al. Comparative hemodynamic depression of sevoflurane versus halothane in infants: an echocardiographic study. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:795–800. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wodey E, Chonow L, Beneux X, Azzis O, Bansard JY, Ecoffey C. Haemodynamic effects of propofol vs thiopental in infants: an echocardiographic study. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:516–20. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dershwitz M, Randel GI, Rosow CE, et al. Initial clinical experience with remifentanil, a new opioid metabolized by esterases. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:619–23. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199509000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]