Abstract

Standardized methodologies for the molecular detection of invasive aspergillosis (IA) have been established by the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative for the testing of whole blood, serum, and plasma. While some comparison of the performance of Aspergillus PCR when testing these different sample types has been performed, no single study has evaluated all three using the recommended protocols. Standardized Aspergillus PCR was performed on 423 whole-blood pellets (WBP), 583 plasma samples, and 419 serum samples obtained from hematology patients according to the recommendations. This analysis formed a bicenter retrospective anonymous case-control study, with diagnosis according to the revised European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) consensus definitions (11 probable cases and 36 controls). Values for clinical performance using individual and combined samples were calculated. For all samples, PCR positivity was significantly associated with cases of IA (for plasma, P = 0.0019; for serum, P = 0.0049; and for WBP, P = 0.0089). Plasma PCR generated the highest sensitivity (91%); the sensitivities for serum and WBP PCR were 80% and 55%, respectively. The highest specificity was achieved when testing WBP (96%), which was significantly superior to the specificities achieved when testing serum (69%, P = 0.0238) and plasma (53%, P = 0.0002). No cases were PCR negative in all specimen types, and no controls were PCR positive in all specimens. This study confirms that Aspergillus PCR testing of plasma provides robust performance while utilizing commercial automated DNA extraction processes. Combining PCR testing of different blood fractions allows IA to be both confidently diagnosed and excluded. A requirement for multiple PCR-positive plasma samples provides similar diagnostic utility and is technically less demanding. Time to diagnosis may be enhanced by testing multiple contemporaneously obtained sample types.

INTRODUCTION

Standardized methodologies for the molecular detection of invasive aspergillosis (IA) when testing whole blood (WB), serum, and plasma have been established by the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative (EAPCRI), but direct comparisons of performance for methods compliant with the recommendations are limited (1–8). The published evidence from the data generated is contradictory. Serum was shown to be superior to the cell pellet in one study, only for another to recommend the use of WB over plasma (4, 5). A recent study showed no significant difference in PCR performance when testing serum or WB (6). Differences between the methodologies used in the studies, particularly sample volumes and DNA extraction protocols, make comparisons difficult, and if suboptimal methods were used for one particular sample type, the assay performance and conclusions could be biased (1, 2).

It is important to compare the different specimen types using optimal methodology and to consider both performance and benefits and drawbacks. From a technical perspective, the use of serum/plasma is convenient, since it permits the use of commercially available manual or automated extraction processes, reduces the time to results, and is in line with generic molecular methods. It also allows a single sample to be drawn for galactomannan (GM) enzyme immunoassay (EIA), β-d-glucan testing, and PCR testing. The testing of WB potentially allows a wider range of DNA sources to be targeted. Comparison of methods compliant with EAPCRI recommendations showed a trend toward increased sensitivity when testing WB, which was usually the first PCR-positive specimen. However, the testing was more technical and time consuming than for serum or plasma (3). Since clot formation may remove IA biomarkers from serum, the use of plasma could avoid this and improve PCR performance, as demonstrated in analytical PCR studies and for galactomannan EIA (8–10). A clinical evaluation showed improved sensitivity when testing plasma compared to the results for serum, while maintaining the methodological simplicity that is essential for widespread acceptance (7, 8). While these studies provide strong evidence for the choice of certain specimen types, no single study compares all three sample types.

This report describes the evaluation of Aspergillus PCR when testing DNA extracted from serum, plasma, and EDTA WB using optimized methods compliant with EAPCRI recommendations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient population.

EDTA WB and serum samples were sent to Public Health Wales, Microbiology Cardiff (PHW), and the University of Würzburg (UKW) for routine Aspergillus PCR and GM EIA diagnostic investigations as part of local screening strategies for hematology patients at risk of IA. On completion of routine testing, excess WB pellet (WBP; EDTA WB minus 1 ml of plasma), plasma, and serum samples were stored at −80°C. Retrospective testing on samples collected over a 6-month period (1 January to 30 June 2013) at PHW and an 11-month period (February to December 2013) at UKW was performed as an anonymous case-control study to assess the performance of Aspergillus PCR assays in different specimen types. All serum and WBP samples were tested by UKW, whereas all plasma samples were tested by PHW. Only samples with sufficient volume according to the EAPCRI recommendations (≥3 ml WB and ≥0.5 ml serum/plasma) were included. Patients with less than three screening sample types were excluded from the final population.

Clinical information was gathered as part of routine diagnostic care, and no further information specific to this study was required. The study was approved by local ethical and research and development boards.

Invasive aspergillosis was defined using revised European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC-MSG) definitions (11). The PCR result was not used to define disease. Probable cases were defined by specific radiology (nodule/halo/cavity on high-resolution computed tomography) plus a positive GM EIA (serum or bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL] fluid) as the mycological criterion. Possible cases were defined by specific radiology alone. Due to diagnostic ambiguity, possible cases were only included as cases for secondary analysis. Basic patient demographics are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of patients with EORTC-MSG diagnosis of IA

| Characteristica | Value(s) for patients withb: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Probable IA (n = 11) | Possible IA (n = 6) | NEF (n = 36) | |

| Male/female | 5/6 | 4/2 | 16/20 |

| Mean age (range) (yr) at: | |||

| UKW | 53 (45–60) | 59 (57–62) | 50 (24–62) |

| PHW | 56 (25–73) | 58 | 56 (21–77) |

| No. of patients with underlying condition | |||

| AML/MDS | 8 | 4 | 19 |

| Lymphoma | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| ALL | 1 | 5 | |

| Myeloma | 3 | ||

| AA | 1 | ||

| CML/CLL | 3 | ||

| Other | 3 | ||

| Median no. of samples per patient | |||

| Plasma | 18 | 11 | 7 |

| Serum | 11 | 9 | 4 |

| WBP | 12 | 8 | 4 |

UKW, University of Würzburg; PHW, Public Health Wales, Microbiology Cardiff; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; lymphoma, Hodgkins, non-Hodgkins, and diffuse large B cell lymphomas; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AA, aplastic anemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphoblastic leukemia; WBP, whole-blood pellet.

IA, invasive aspergillosis; NEF, no evidence of fungal disease (control population).

Galactomannan EIA.

Both centers performed their own GM EIA testing on serum samples using the Platelia Aspergillus EIA kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and all runs were required to meet the designated validity criteria. The GM EIA was considered positive when the optical density index was ≥0.5 on at least one occasion.

DNA extraction.

All manual DNA extraction steps were performed in a class 2 laminar flow cabinet and were compliant with EAPCRI recommendations (1, 2, 8). When testing plasma at PHW, DNA was extracted from 0.5 ml of undiluted plasma using the commercially available DSP virus kit on the Qiagen EZ1 XL Advance automated extractor, following the manufacturer's instructions, and DNA was eluted in a 60-μl volume. At UKW, DNA was extracted from 1.0 ml of 306 undiluted serum samples and 0.5 to <1.0 ml of 114 undiluted serum samples using the commercially available Qiagen UltraSens virus kit, following the manufacturer's instructions with the following modifications: (i) no carrier RNA was used, (ii) lysate centrifugation was adjusted to 3,000 × g, and (iii) the elution buffer volume was increased to 70 μl and incubated on the column at room temperature for 2 min before tubes were centrifuged for 2 min (3). At UKW, the WBP was extracted using standardized methods as described previously (1, 12). Briefly, red and white cells from 3 ml of EDTA blood were lysed and centrifuged. The pellet was bead beaten to lyse fungal cells. DNA was isolated by using a commercially available kit (High Pure PCR template preparation kit; Roche). The elution volume was 70 μl. In each extraction procedure, at least one negative control was included. At PHW, extractions included a positive control (plasma spiked with 20 genomes of A. fumigatus DNA) and a negative control (plasma from a healthy donor). At UKW, negative controls were included to monitor for contamination.

PCR amplification.

The PCR methods followed EAPCRI recommendations, including using an internal control PCR to monitor inhibition (1, 2).

At UKW, an Aspergillus-specific real-time PCR assay targeting the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1)–5.8S rRNA gene region was used as previously described (13). The final reaction mixture volume was 21 μl, containing 0.3 μM forward primer, 0.3 μM reverse primer, 0.15 μM hydrolysis probe, 10 μl TaqMan gene expression master mix (Applied Biosystems), and 10 μl template DNA. Amplification was performed using a StepOnePlus machine (Applied Biosystems) with the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min and 60 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 54°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 1 s. Negative and positive PCR controls and internal control PCRs were included for every run (13).

At PHW, the Aspergillus real-time PCR test was performed for 50 cycles as a single-round assay using a Rotorgene Q HRM instrument (Qiagen, United Kingdom) targeting the 28S rRNA gene as previously described (14). The final reaction mixture volume was 50 μl, containing 0.75 μM primers, 0.4 μM hydrolysis probe, 4 mM MgCl2, 5 μl Roche LightCycler hybridization master mix (Roche, United Kingdom), 9 μl molecular-grade water, and 15 μl template DNA. PCR controls in the form of cloned PCR products (300, 30, and 3 input copies) and no-template molecular-grade water were included to monitor PCR performance.

Both centers tested each sample in duplicate. The analytical threshold was defined by at least one replicate generating a positive signal at any cycle during the PCR.

Despite utilizing different DNA extraction kits and PCR methods, the levels of performance at UKW and PHW were equivalent when participating in EAPCRI studies (1–3, 7).

Statistical analysis.

Patients with EORTC/MSG-defined proven and probable IA were classified as cases, and patients with no evidence of fungal disease were categorized as controls (11). Possible cases were included in a secondary analysis as additional cases to provide comparative performance with GM EIA while minimizing incorporation bias by representing false-negative GM EIA cases. The validity of positive PCR results was determined by comparing the rate of positivity in samples originating from cases to the rate of false positives in control samples. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) were generated for each proportionate value, and where required, P values (Fisher's exact test, P = 0.05) were used to determine significance (15). The clinical performance, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR−, respectively), and diagnostic odds ratio of the PCR assays when testing each specimen type were calculated using 2-by-2 tables, using single and multiple (≥2) positives as significant. For each patient, multiple positive samples across the duration of sampling (median, 74 days; range, 7 to 178) were considered. Data were analyzed in two ways, as follows: first, using all specimens collected for each patient, where the total number of samples may have varied between specimen types, and second, including only sample sets where all three specimen types were contemporaneously available (i.e., blood drawn in the same collection). Classification and regression tree analysis (CART) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis were performed to determine the probability of IA being in accordance with PCR positivity in various specimen types. For cases of IA, the first sample to become positive was identified, and the timing of PCR positivity was compared to the IA EORTC/MSG probable diagnosis.

RESULTS

Totals of 586 GM and 583 plasma PCR tests were performed on samples from 11 cases of probable IA (GM, 194 samples, and plasma PCR, 194 samples), 6 cases of possible IA (GM, 62 samples, and plasma PCR, 62 samples), and 36 patients with no evidence of fungal disease (NEF) (GM, 330 samples, and plasma PCR, 327 samples). Four hundred twenty-three WBP PCR tests were performed on samples from 11 cases of probable IA (n = 147 samples), 6 cases of possible IA (n = 61 samples), and 25 NEF patients (n = 215 samples). Four hundred nineteen serum PCR tests were performed on samples from 10 cases of probable IA (n = 125 samples), 6 cases of possible IA (n = 60 samples), and 26 patients with NEF (n = 234 samples). There were no cases of proven IA. Three hundred seventy-six sample sets (probable IA, 117 sets; possible IA, 60 sets; and NEF, 199 sets) where serum, plasma, and WBP were contemporaneously drawn from 10 cases of probable IA, 6 cases of possible IA, and 24 patients with NEF were tested. The overall incidence of probable IA in the selected case-control cohort was 20.8% (11/53).

Sample positivity rates.

The true-positive rates for plasma, serum, and WBP PCR are shown in Table 2. When testing all samples, the true-positive rate for plasma PCR was significantly higher than that for WBP PCR (P = 0.0141), while there was a trend toward a higher true-positive rate for serum PCR than for WBP PCR (P = 0.0906) but there was no significant difference between the true-positive rates for serum and plasma PCR (P = 0.6242). The false-positive rates for all specimen types were significantly lower than the corresponding true-positive rates (for plasma, P = 0.0019; for serum, P = 0.0049; and for WBP, P = 0.0089). There was no difference in positivity rates between all samples and samples drawn contemporaneously (Table 2). Again, the false-positive rates for contemporaneously drawn samples were significantly lower than the true-positive rates (for plasma, P = 0.0045; for serum, P = 0.0229; and for WBP, P = 0.0145).

TABLE 2.

Aspergillus PCR positivity rates when testing DNA extracted from plasma, serum, and whole-blood pellet

| Populationa | Value(s) [no. of positive samples/total no. of samples, % (95% CI)] obtained usingb: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma PCR | Serum PCR | WBP PCR | |

| All samples | |||

| Probable IA | 29/194, 15.0 (10.6–20.6) | 16/126, 12.7 (8.0–19.6) | 9/147, 6.1 (3.3–11.2) |

| NEF | 21/327, 6.4 (4.2–9.6) | 10/234, 4.3 (2.3–7.7) | 2/215 (0.9 (0.3–3.2) |

| Contemporaneously taken samples | |||

| Probable IA | 18/117, 15.4 (10.0–23.0) | 14/117, 12.0 (7.3–19.1) | 7/117, 6.0 (2.9–11.8) |

| NEF | 11/199, 5.5 (3.1–9.6) | 9/199, 4.5 (2.4–8.4) | 2/199, 1.0 (0.2–3.6) |

IA, invasive aspergillosis; NEF, no evidence of fungal disease.

CI, confidence interval; WBP, whole-blood pellet.

Clinical performance.

Clinical performance is summarized in Tables 3 and 4. When all available samples were included (Table 3), plasma PCR generated the highest sensitivity, although not significantly greater than that of serum PCR (P = 1.00) or WBP PCR (P = 0.1486). The highest specificity was achieved when testing WBP and was significantly superior to the specificities achieved when testing serum (P = 0.0238) and plasma (P = 0.0002) and using a single positive PCR result as significant. The specificity of serum PCR was not significantly greater than that of plasma PCR (P = 0.2941). When using a threshold requiring two or more samples to be PCR positive, the sensitivity of plasma PCR remained highest but did not achieve statistical significance over the sensitivities of serum and WBP PCR, although the specificities of both the serum and plasma PCR assays increased, becoming comparable to that of WBP PCR. WBP PCR showed no improvement when using the more stringent threshold (Table 3). If a threshold requiring positive PCR results in consecutive samples was utilized, the sensitivity and specificity of plasma PCR were 54.5% and 97.2%, while the specificity of serum and WBP PCR was 100%, although the sensitivities were <18%. Optimal performance as determined by the diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) was obtained when using plasma PCR with the requirement of multiple positive samples to be significant. The same pattern emerged when analyzing results from contemporaneously drawn samples, where plasma PCR had the highest sensitivity/LR− and WBP PCR provided the greatest specificity/LR+ (Table 4). The optimal performance (DOR, 23.0) was generated by plasma PCR when using a multiple-positive threshold and by WBP PCR when using a single-positive threshold. If possible cases were included, the sensitivities of plasma, serum, and WBP PCR when testing contemporaneously drawn samples were 81.3% (13/16), 68.8% (11/16), and 50% (8/16), respectively.

TABLE 3.

Clinical performance of Aspergillus PCR when testing all plasma, serum, and whole-blood pellet samples

| Parametera | Value(s) [% (95% CI) or indicated ratio] for indicated sample type and positivity threshold (single or multiple positive PCRs)b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum (10 cases and 26 controls) |

Plasma (11 cases and 36 controls) |

Whole-blood pellet (11 cases and 25 controls) |

||||

| Single | Multiple | Single | Multiple | Single | Multiple | |

| Sensitivity | 80.0 (49.0–94.3) | 60.0 (31.3–83.2) | 90.9 (48.7–99.7) | 81.8 (40.3–97.7) | 54.5 (19.9–85.6) | 27.3 (5.5–67.2) |

| Specificity | 69.2 (50.0–83.6) | 92.3 (75.8–97.9) | 52.8 (32.0–72.7) | 91.7 (71.5–98.4) | 96.0 (80.5–99.3) | 96.0 (80.5–99.3) |

| LR+ | 2.6 | 7.80 | 1.93 | 9.86 | 13.63 | 6.82 |

| LR− | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.47 | 0.76 |

| DOR | 8.96 | 18.14 | 11.35 | 54.78 | 29.00 | 8.97 |

LR+ and LR−, positive and negative likelihood ratios; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio.

The multiple positivity threshold requires ≥2 positive PCRs. Values showing optimal performance are in boldface. CI, confidence interval.

TABLE 4.

Clinical performance of Aspergillus PCR when testing contemporaneously drawn plasma, serum, and whole-blood pellet samples from probable IA and NEF patients

| Parametera | Value(s) [% (95% CI) or indicated ratio] for indicated sample type and positivity threshold (single or multiple positive PCRs)b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum |

Plasma |

Whole-blood pellet |

||||

| Single | Multiple | Single | Multiple | Single | Multiple | |

| Sensitivity | 80.0 (36.9–97.5) | 50.0 (16.0–84.0) | 90.0 (45.6–99.7) | 50.0 (16.0–84.0) | 50.0 (16.0–84.0) | 20.0 (2.5–63.1) |

| Specificity | 70.8 (43.5–88.9) | 91.7 (65.3–99.0) | 58.3 (32.4–80.6) | 95.8 (70.5–99.9) | 95.8 (70.5–99.9) | 95.8 (70.5–99.9) |

| LR+ | 2.74 | 6.0 | 2.16 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 4.80 |

| LR− | 0.28 | 0.55 | 0.17 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.84 |

| DOR | 9.71 | 11.00 | 12.60 | 23.00 | 23.00 | 5.75 |

LR+ and LR−, positive and negative likelihood ratios; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio.

The multiple positivity threshold requires ≥2 positive PCRs. Patients included 10 cases of probable IA and 24 patients with no evidence of fungal disease (NEF). Values showing optimal performance are in boldface. CI, confidence interval.

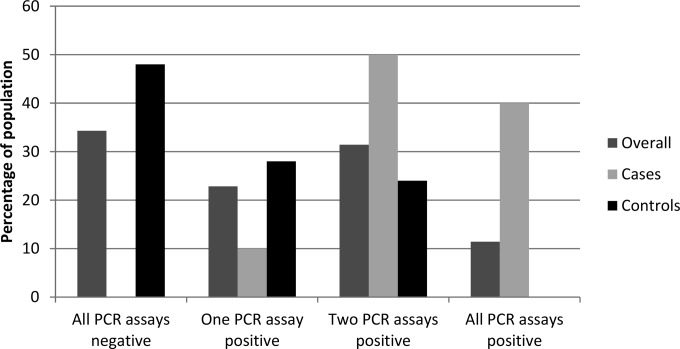

The percentages of the overall population, cases, and controls and the distribution of the numbers of specimen types (serum, plasma, and WBP) that were PCR positive when considering all available specimens are shown in Fig. 1. All cases of probable IA were positive by at least one of the three PCR assays. Consequently, if a patient was negative by all three assays, the sensitivity was 100% and the LR− was <0.002 (Table 5). Conversely, no NEF patients were positive by all three tests or by plasma and WBP PCR, generating a specificity of 100%. Ninety percent of cases of probable IA were positive by two PCR tests, compared to 6/25 NEF patients (difference of 66.0%; P = 0.0006). Using a threshold of ≥2 positive assays generated sensitivity and specificity of 90.0% and 76.0%, respectively, and an LR− of 0.13 (Table 5).

FIG 1.

Percentages of positive PCR assays in the overall hematology population (n = 35), cases of probable IA (n = 10), and patients with no evidence of fungal disease (n = 25). Data for patients that did not have PCR performed on all three specimen types were excluded (n = 12).

TABLE 5.

Combined performance of the plasma, serum, and WBP PCR tests using different positivity thresholdsa

| Parametera | Value(s)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any one assay | Two of three assays | All three assays | |

| Sensitivity | 10/10, 100 (72.3–100) | 9/10, 90.0 (59.6–98.2) | 4/10, 40.0 (16.8–68.7) |

| Specificity | 12/25, 48.0 (30.0–66.5) | 19/25, 76.0 (56.6–88.5) | 25/25, 100 (86.7–100) |

| LR+ | 1.92 | 3.75 | >400c |

| LR− | <0.002c | 0.13 | 0.60 |

| DOR | >960c | 28.8 | >666.7c |

LR+ and LR−, positive and negative likelihood ratios; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio.

Values for sensitivity and specificity are number of positive samples/total number of samples, followed by percentage (95% CI), observed when the indicated number of PCR assays was positive. Patients that did not have PCR performed on all three specimen types were excluded (n = 12). Values showing optimum performance are in boldface.

In order to provide a value in place of ∞, the ratio was calculated using a value of 99.9% instead of 100%.

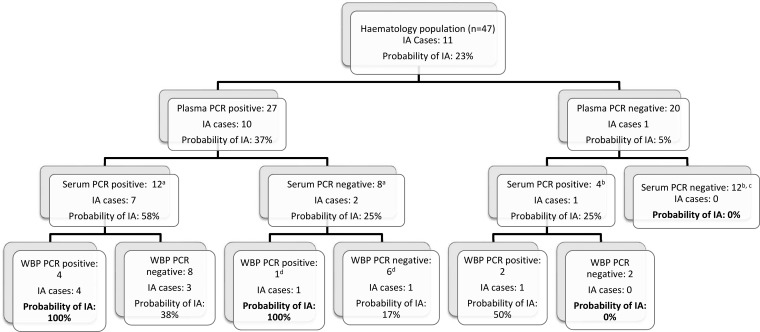

The PCR positivities when combining different specimen types and the resulting probability of IA are shown in Fig. 2. As plasma PCR had the greatest sensitivity, this was used as the primary screen, followed by serum and WBP PCR. If a patient was plasma PCR positive, the probability of IA increased from a pretest probability of 23% to 37%, whereas if the patient was plasma PCR negative, it was reduced to 5%. If the patient was PCR positive in further specimen types, the probabilities increased to 58% and 100% for positive serum PCR and positive WBP PCR, respectively. Conversely, if a patient was PCR negative in plasma and serum or WBP, the probability of IA was 0% (Fig. 2). ROC analysis of this algorithm generated an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.71 to 1.00).

FIG 2.

Probabilities of invasive aspergillosis (IA) according to various degrees of PCR positivity. a 1 case and 6 controls had no serum PCR performed; b 4 controls had no serum PCR performed; c all 12 controls were also whole-blood-pellet (WBP) PCR negative; d 1 control had no WBP PCR performed.

Comparison of PCR with serum GM EIA.

To minimize the effects of incorporation bias associated with GM EIA testing, both probable (radiology plus GM EIA) and possible IA (radiology only) cases (n = 17) were included, along with NEF patients (n = 36). The true-positive rates from cases of IA for serum GM EIA, plasma PCR, serum PCR, and WBP PCR were 9.0% (23/256; 95% CI, 6.1 to 13.1), 13.7% (35/256; 95% CI, 10.0 to 18.4), 10.8% (20/186; 95% CI, 7.1 to 16.0), and 6.7% (14/208; 95% CI, 4.1 to 11.0), respectively. The false-positive rate from NEF patients for serum GM EIA was 3.3% (11/330; 95% CI, 1.9 to 5.9), comparable to the rates for plasma and serum PCR reported above. The sensitivities of serum GM EIA, plasma PCR, serum PCR, and WBP PCR when testing all samples from probable/possible IA cases were 47.1% (95% CI, 19.9 to 75.9), 82.4% (95% CI, 49.1 to 96.5), 68.8% (95% CI, 44.4 to 85.8), and 52.9% (95% CI, 24.1 to 80.1), respectively. The specificity of GM EIA was 86.1% (95% CI, 64.8 to 95.8) (for PCR specificities, see Table 3).

Time to assay positivity.

Of the 10 cases of probable IA tested by all tests, four were first PCR positive in plasma, three patients had positive plasma PCRs simultaneously with serum GM EIA (n = 2) or serum PCR (n = 1), and in three patients, serum GM EIA was the earliest positive test. The median times to assay positivity with reference to the date of diagnosis of EORTC/MSG-defined probable IA were −8.5 days (range, −98 to +28 days), −2 days (range, −61 to +31 days), +1.5 days (range, −10 to +70 days), and −1 day (range, −32 to +5 days) for plasma PCR, serum PCR, WBP PCR, and serum GM EIA, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Various sample types have been used for Aspergillus PCR testing (16). Given the relatively low incidence of disease (5 to 15% in high-risk populations) and the reliance on often unnecessary empirical therapy, it makes sense to exclude disease using tests with a high sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) (17). As Aspergillus conidia are inhaled daily, there is a continuous window for the initiation of infection, and thus, frequent testing is required for screening to facilitate early diagnosis and avoid delayed therapy and the associated morbidity. This excludes the use of invasive biopsies or bronchoalveolar lavage fluids, which are better suited to confirmation of clinically suspected IA. The testing of blood allows high-frequency screening, but different fractions contain different Aspergillus targets, requiring specific protocols for efficient DNA extraction (1, 2). Until recently, these processes lacked methodological standardization, and comparisons of the performance of PCR when testing the different fractions often predated methodological recommendations or did not evaluate all available sample types (3–7).

The current study is the first to compare the performance of PCR when testing DNA extracted from serum, plasma, and WBP using internationally standardized methods (1, 2, 8). It showed that the PCR positivity was significantly associated with cases of IA irrespective of the specimen type and that PCR positivity in multiple sample types had diagnostic utility (Fig. 2). The highest sensitivity was achieved when testing plasma, supporting the recent analytical and clinical evaluations of the EAPCRI, where plasma PCR was preferred over serum PCR (7, 8). In the previous clinical evaluation, the quantification cycle (Cq) values were significantly lower for PCR-positive plasma samples from cases of IA than for controls, whereas the Cq values for true and false positives when testing serum samples were indistinguishable (7). In the current study, there were no differences in true- and false-positive Cq values for either serum or WBP PCR (results not shown). When testing plasma, PCR positives from cases of IA generated Cq values (40.9 cycles) that were significantly lower (P = 0.0189) than those associated with control samples (42.5 cycles), confirming the previous research.

In the laboratory setting, PCR testing of all three specimen types would not be cost effective. However, the extraction of serum and plasma samples is identical, and it is feasible to combine serum/plasma and WBP extraction in a single efficient process (18). With sensitivity paramount in screening protocols, it is proposed that plasma PCR should be utilized as the primary screen (Fig. 2). In this retrospective study, the incidence of IA was 23% (possible IA excluded); at more typical incidences of 10% and 5%, the posttest probabilities of IA associated with a negative plasma PCR result would be 2.5% and 1.3%, respectively. If the WBP or serum was also PCR negative, then the posttest probability of IA was 0% (Fig. 2). The area under the ROC curve for this predictive model (AUC, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.00) compares favorably with those of similar models for the diagnosis of invasive candidal disease (AUC, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.81) and IA when combining PCR and antigen detection (AUC, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87 to 0.95) (19, 20).

The highest specificity for a single PCR was associated with testing WBP (96%), but sensitivity was compromised (55%). For serum and plasma, the specificity was improved by requiring multiple PCR-positive samples, which increased the specificity of plasma PCR to 92% with only a slight reduction in sensitivity (82%) (Table 3). This positivity threshold provided the greatest overall diagnostic performance (DOR, 55) and is in keeping with the findings of a meta-analysis of Aspergillus PCR testing of blood samples (21). Performing PCR on all three sample types permitted IA to be both excluded if all were negative and confidently diagnosed if all were positive, but a confident diagnosis was also possible if both WBP and plasma PCR were positive, which is convenient given that the extraction processes for these sample types can be combined (Fig. 2 and Table 4) (18). Using a threshold of 2/3 sample types being PCR positive generated overall performance that was similar to that of plasma PCR. The probability of IA when the patient was PCR positive in two sample types was 53% (range, 50% serum and WBP PCR positive to 100% plasma and WBP PCR positive), compared to 75% if the patient had multiple plasma samples that were PCR positive. One drawback of requiring multiple plasma samples to be PCR positive over testing multiple contemporaneous specimen types is the delay incurred in testing additional samples at later time points.

Interestingly, the performance of WBP PCR was significantly inferior to the results from previous studies testing WB, possibly a result of prolonged storage and the fact that 1 ml of plasma had been removed from the EDTA WB sample for initial processing (3, 14, 16, 22). Although the EAPCRI recommendations for processing WB were followed, they were designed to target fungal cells in the circulation, whether phagocytosed, inert, or actively invading blood vessels. Storage of samples at −80°C could lyse fungal cells, providing an extracellular source of fungal DNA. Standardized WB protocols are not optimized for extraction from these sources, as the erythrocyte lysis steps may remove extracellular DNA (1). Alternative methods that target both free and cell-associated fungal DNA may have overcome this issue (18).

This study confirms that Aspergillus PCR testing of plasma provides robust performance while requiring simple, possibly automated DNA extraction processes. Aspergillus PCR testing of plasma appears to be the optimal approach. However, repeat or combination confirmatory testing is required for diagnostic accuracy. Although the performance with combined sample types is not superior to testing plasma alone, time to diagnosis may be improved by testing multiple contemporaneously drawn sample types. It is not yet clear whether confirmatory testing should be in the form of a secondary molecular test or through antigen testing. Recent clinical trials, prospective diagnostic testing, and meta-analysis favor a combined molecular-antigen approach (20, 23–25). However, methodological differences, including the various sample types used for PCR, and the potential incorporation bias associated with antigen testing need to be considered before finalizing a strategy. Further clinical evaluation and systematic review comparing Aspergillus PCR testing of the different blood fractions are required before a final answer on the optimal specimen type or types is achieved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by a Pfizer Europe ASPIRE grant (project number WS2263001).

We also acknowledge the efforts of the EAPCRI in providing recommendations for optimal sample processing and maximizing the potential of this study.

J.S. declares no conflicts of interest. P.L.W. is a founding member of the EAPCRI, received project funding from Myconostica, Luminex, and Renishaw diagnostics, was sponsored by Myconostica, MSD, and Gilead Sciences to attend international meetings, was on a speaker's bureau for Gilead Sciences, and provided consultancy for Renishaw Diagnostics Limited. S.H. declares no conflicts of interest. D.M. declares no conflicts of interest. R.A.B. is a founding member of the EAPCRI, received an educational grant and scientific fellowship award from Gilead Sciences and Pfizer, is a member of the advisory board and speaker bureau for Gilead Sciences, MSD, Astellas, and Pfizer, and was sponsored by Gilead Sciences and Pfizer to attend international meetings. H.E. declares no conflicts of interest. J.L. is a founding member of the EAPCRI, received an educational grant and scientific fellowship award from Pfizer, and was sponsored by Astellas to attend international meetings.

REFERENCES

- 1.White PL, Bretagne S, Klingspor L, Melchers WJG, McCulloch E, Schulz B, Finnstrom N, Mengoli C, Barnes RA, Donnelly JP, Loeffler J, European Aspergillus PCR Initiative . 2010. Aspergillus PCR: one step closer to standardization. J Clin Microbiol 48:1231–1240. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01767-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White PL, Mengoli C, Bretagne S, Cuenca-Estrella M, Finnstrom N, Klingspor L, Melchers WJ, McCulloch E, Barnes RA, Donnelly JP, Loeffler J, European Aspergillus PCR Initiative (EAPCRI) . 2011. Evaluation of Aspergillus PCR protocols for testing serum specimens. J Clin Microbiol: 49:3842–3848. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05316-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Springer J, Morton CO, Perry M, Heinz WJ, Paholcsek M, Alzheimer M, Rogers TR, Barnes RA, Einsele H, Loeffler J, White PL. 2013. Multicenter comparison of serum and whole-blood specimens for detection of Aspergillus DNA in high-risk hematological patients. J Clin Microbiol 51:1445–1450. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03322-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeffler J, Hebart H, Brauchle U, Schumacher U, Einsele H. 2000. Comparison between plasma and whole blood specimens for detection of Aspergillus DNA by PCR. J Clin Microbiol 38:3830–3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa C, Costa JM, Desterke C, Botterel F, Cordonnier C, Bretagne S. 2002. Real-time PCR coupled with automated DNA extraction and detection of galactomannan antigen in serum by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 40:2224–2227. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2224-2227.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernal-Martínez L, Gago S, Buitrago MJ, Gomez-Lopez A, Rodríguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M. 2011. Analysis of performance of a PCR-based assay to detect DNA of Aspergillus fumigatus in whole blood and serum: a comparative study with clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol 49:3596–3599. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00647-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White PL, Barnes RA, Springer J, Klingspor L, Cuenca-Estrella M, Morton CO, Lagrou K, Bretagne S, Melchers WJ, Mengoli C, Donnelly JP, Heinz WJ, Loeffler J. 2015. Clinical performance of Aspergillus PCR for testing serum and plasma: a study by the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. J Clin Microbiol 53:2832–2837. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00905-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loeffler J, Mengoli C, Springer J, Bretagne S, Cuenca-Estrella M, Klingspor L, Lagrou K, Melchers WJ, Morton CO, Barnes RA, Donnelly JP, White PL. 2015. Analytical comparison of in vitro-spiked human serum and plasma for PCR-based detection of Aspergillus fumigatus DNA: a study by the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. J Clin Microbiol 53:2838–2845. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00906-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White PL, Jones T, Whittle K, Watkins J, Barnes RA. 2013. Comparison of galactomannan enzyme immunoassay performance levels when testing serum and plasma samples. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:636–638. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00730-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCulloch E, Ramage G, Jones B, Warn P, Kirkpatrick WR, Patterson TF, Williams C. 2009. Don't throw your blood clots away: use of blood clot may improve sensitivity of PCR diagnosis in invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Pathol 62:539–541. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.063321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Muñoz P, Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, JEBennett; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group . 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 46:1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Springer J, Loeffler J, Heinz W, Schlossnagel H, Lehmann M, Morton O, Rogers TR, Schmitt C, Frosch M, Einsele H, Kurzai O. 2011. Pathogen-specific DNA enrichment does not increase sensitivity of PCR for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic patients. J Clin Microbiol 49:1267–1273. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01679-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Springer J, Lackner M, Nachbaur D, Girschikofsky M, Risslegger B, Mutschlechner W, Fritz J, Heinz WJ, Einsele H, Ullmann AJ, Löffler J, Lass-Flörl C. 20 September 2015. Prospective multicentre PCR-based Aspergillus DNA screening in high-risk patients with and without primary antifungal mould prophylaxis. Clin Microbiol Infect. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White PL, Linton CJ, Perry MD, Johnson EM, Barnes RA. 2006. The evolution and evaluation of a whole blood polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of invasive aspergillosis in hematology patients in a routine clinical setting. Clin Infect Dis 42:479–486. doi: 10.1086/499949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcombe RG. 1998. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: comparison of eleven methods. Stat Med 17:873–890. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White PL, Barnes RA. 2009. Aspergillus PCR, p 373–390. In Latge J-P, Steinbach WJ (ed), Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnelly JP, Maertens J. 2013. The end of the road for empirical antifungal treatment? Lancet Infect Dis 13:470–472. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Springer J, Schloßnagel H, Heinz W, Doedt T, Soeller R, Einsele H, Loeffler J. 2012. A novel extraction method combining plasma with a whole-blood fraction shows excellent sensitivity and reproducibility for patients at high risk for invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 50:2585–2591. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00523-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.León C, Ruiz-Santana S, Saavedra P, Castro C, Ubeda A, Loza A, Martín-Mazuelos E, Blanco A, Jerez V, Ballús J, Alvarez-Rocha L, Utande-Vázquez A, Fariñas O. 2012. Value of β-d-glucan and Candida albicans germ tube antibody for discriminating between Candida colonization and invasive candidiasis in patients with severe abdominal conditions. Intensive Care Med 38:1315–1325. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2616-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes RA, Stocking K, Bowden S, Poynton MH, White PL. 2013. Prevention and diagnosis of invasive fungal disease in high-risk patients within an integrative care pathway. J Infect 67:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mengoli C, Cruciani M, Barnes RA, Loeffler J, Donnelly JP. 2009. Use of PCR for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: systematic review of and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 9:89–96. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loeffler J, Henke N, Hebart H, Schmidt D, Hagmeyer L, Schumacher U, Einsele H. 2000. Quantification of fungal DNA by using fluorescence resonance energy transfer and the Light Cycler system. J Clin Microbiol 38:586–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrissey CO, Chen SC, Sorrell TC, Milliken S, Bardy PG, Bradstock KF, Szer J, Halliday CL, Gilroy NM, Moore J, Shcwarer AP, Guy S, Bajel A, Tramontana AR, Spelman T, Slavin MA, Australasian Leukaemia Lymphoma Group, the Australia and New Zealand Mycology Interest Group . 2013. Galactomannan and PCR versus culture and histology for directing use of antifungal treatment for invasive aspergillosis in high-risk haematology patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 13:519–528. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguado JM, Vázquez L, Fernández-Ruiz M, Fernandez-Ruiz M, Villaescusa T, Ruiz-Camps I, Barba P, Silva JT, Batlle M, Solano C, Gallardo D, Heras I, Polo M, Varela R, Vallejo C, Olave T, Lopez-Jimenez J, Rovira M, Parody R, Cuenca-Estrella M, PCRAGA Study group, Spanish Stem Cell Transplantation Group, Study Group of Medical Mycology of the Spanish Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases . 2015. Serum galactomannan versus a combination of galactomannan and PCR-based Aspergillus DNA detection for early therapy of invasive aspergillosis in high-risk hematological patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 60:405–414. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arvanitis M, Anagnostou T, Mylonakis E. 2015. Galactomannan and polymerase chain reaction-based screening for invasive aspergillosis among high-risk hematology patients: a diagnostic meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 61:1263–1272. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]