Abstract

Actinomyces species are uncommon but important causes of invasive infections. The ability of our regional clinical microbiology laboratory to report species-level identification of Actinomyces relied on molecular identification by partial sequencing of the 16S ribosomal gene prior to the implementation of the Vitek MS (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry [MALDI-TOF MS]) system. We compared the use of the Vitek MS to that of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for reliable species-level identification of invasive infections caused by Actinomyces spp. because limited data had been published for this important genera. A total of 115 cases of Actinomyces spp., either alone or as part of a polymicrobial infection, were diagnosed between 2011 and 2014. Actinomyces spp. were considered the principal pathogen in bloodstream infections (n = 17, 15%), in skin and soft tissue abscesses (n = 25, 22%), and in pulmonary (n = 26, 23%), bone (n = 27, 23%), intraabdominal (n = 16, 14%), and central nervous system (n = 4, 3%) infections. Compared to sequencing and identification from the SmartGene Integrated Database Network System (IDNS), Vitek MS identified 47/115 (41%) isolates to the correct species and 10 (9%) isolates to the correct genus. However, the Vitek MS was unable to provide identification for 43 (37%) isolates while 15 (13%) had discordant results. Phylogenetic analyses of the 16S rRNA sequences demonstrate high diversity in recovered Actinomyces spp. and provide additional information to compare/confirm discordant identifications between MALDI-TOF and 16S rRNA gene sequences. This study highlights the diversity of clinically relevant Actinomyces spp. and provides an important typing comparison. Based on our analysis, 16S rRNA gene sequencing should be used to rapidly identify Actinomyces spp. until MALDI-TOF databases are optimized.

INTRODUCTION

Actinomyces species are uncommon human bacterial pathogens that can cause a wide variety of invasive infections (1). The Actinomyces genus is part of the family Actinomycetaceae, of which there are currently 47 published species, but several novel Actinomyces taxa have recently been described by molecular analyses targeting the ribosomal 16S rRNA gene (2). For example, the Human Oral Microbiome Database (www.homd.org) currently reports many species-level Actinomyces taxa that have not yet been named (3). The pathogenic role of known and novel Actinomyces spp. in contributing alone or as part of polymicrobial flora to human invasive infections is underappreciated because many clinical microbiology laboratories continue to rely on phenotypic methods for identification (4–7). Because Actinomyces spp. grow best under anaerobic conditions and are notoriously fastidious, slow-growing organisms, they may be missed as important pathogens by routine aerobic culture techniques and incubation periods (2, 8).

Upon microscopic examination, Actinomyces isolates typically appear as Gram-positive bacilli that may be coryneform-like with palisading or branching structures and have a positive catalase reaction. Commercial biochemical identification panels for aerobic and anaerobic Gram-positive bacilli include the API Coryne (bioMérieux) and the Vitek ANC cards (bioMérieux) and have less than optimal performance for accurately identifying many clinically relevant Actinomyces spp. (9, 10). Although matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) is widely being adopted into clinical laboratory practice, there have been limited reports comparing the performance of MALDI-TOF MS to that of molecular methods for the identification of Actinomyces spp. (11–15).

Our laboratory routinely uses fast partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (V1 to V3 region) to identify a wide variety of Gram-positive bacilli that are important primary pathogens or that are clinically relevant as part of polymicrobial invasive infections when isolated from clinical specimens (16). More than one hundred cases of invasive Actinomyces spp. infections have been diagnosed by our laboratory in recent years by 16S rRNA sequencing. We were therefore interested in evaluating the ability of the Vitek MS (MALDI-TOF) to identify the diverse array of Actinomyces spp. recovered and in comparing its performance to the gold standard of 16S rRNA sequencing. Phylogenetic analysis of all available 16S rRNA sequence data was also used to determine if any Actinomyces spp. were associated with specific types of infection and to provide additional confirmation/clarity of discordant identifications between the two typing methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Laboratory setting.

Calgary Laboratory Services (CLS) is a large centralized regional clinical laboratory performing most diagnostic infectious diseases testing for a health care region that services ∼1.5 million people in urban and rural centers.

Samples.

Actinomyces spp. isolates described in this study were recovered from clinical specimens tested by CLS over a 4-year period (2011 to 2014). All isolates were anaerobic or aerotolerant Gram-positive bacilli that were catalase positive. Molecular identification was done by fast partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (523 bp) with MicroSeq 500 kits and an ABI Prism 3130 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using standard methods (16). A BLAST search against the SmartGene Integrated Database Network System (IDNS) for bacteria indicated the most closely related species, and the overall identity score for all isolates was ≥99.9% with 0 to 2 mismatches (17, 18). Some isolates had also been tested using the Vitek ANC card (bioMérieux), but few could be definitively identified using phenotypic tests (data not shown). All isolates were also identified using a commercial mass spectrometry system (Vitek MS, ACQ Software R2 version 1.4.2b; bioMérieux) using Myla version 3.2.0-4 in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Ethanol-formic acid extraction was performed on all isolates using the protocol provided by the manufacturer. A quantity of 1 μl of the extracted supernatant was placed on the steel target plate, dried, and overlaid with 1 μl of matrix. The target plate was then loaded into the Vitek MS instrument for analysis. Samples were repeated if the result gave low discrimination or no identification (ID).

Phylogenetic analysis.

The clinical sequences (n = 115) and reference sequences (n = 15) from the SILVA database (19, 20) were aligned with MAFFT (version 7.123b) (21) and were visualized in AliView (version 1.18) (22). The multiple-sequence alignment columns containing over 20% gaps were trimmed with trimAL (version 1.2), which resulted in a 432-bp alignment length (23). A neighbor-joining tree was inferred with 100 bootstrap replicates, and evolutionary distances were computed using the Jukes-Cantor method in MEGA5 (24). Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in <50% of bootstrap replicates were collapsed. The tree was manually rooted on a taxonomic outlier (Trueperella pyogenes; GenBank accession number JN578112) using FigTree (25), with additional color coding of the tree done with the Ape and Picante packages in R (26, 27).

Data analysis.

All data pertaining to individual isolate identification, the 16S rRNA sequence, and the site/source data were entered into Microsoft Excel, and the data were analyzed using standard methods. Data were sorted and filtered to determine the distribution of individual Actinomyces spp. recovered from particular types of invasive infections. The performances of MALDI-TOF and 16S rRNA sequencing for identification of Actinomyces spp. to the genus and species levels in addition to incorrect or absent identification by Vitek MS were compared using a Pivot table.

Ethics.

The conjoint health ethics board at the University of Calgary approved this study (Ethics ID number 23985).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All sequences were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers KJ937784 to KJ937885 and KP192309 to KP192321.

RESULTS

Patient demographics.

A total of 115 individual patients with invasive Actinomyces spp. infections were enrolled during the study period. Most of them were adults (n = 104, 90.5%), and the remainder were children of ≤14 years of age (n = 11, 9.5%). Among the pediatric cases, there was an equal prevalence of disease between girls (n = 5, 46%) and boys (n = 6, 54%), and their ages were similar; girls were aged 7.0 years ± 4.1 standard deviation (SD) (range, 3 to 13 years) while boys were aged 5.6 years ± 4.1 SD (range, 2 to 11 years). Among the adult cases, more disease occurred in males (n = 57, 55%) than in females (n = 47, 45%), but their ages were comparable; females were aged 51.5 years ± 20.3 SD (range, 20 to 96 years), and males were aged 56 years ± 17.2 SD (range, 22 to 91 years).

Epidemiology.

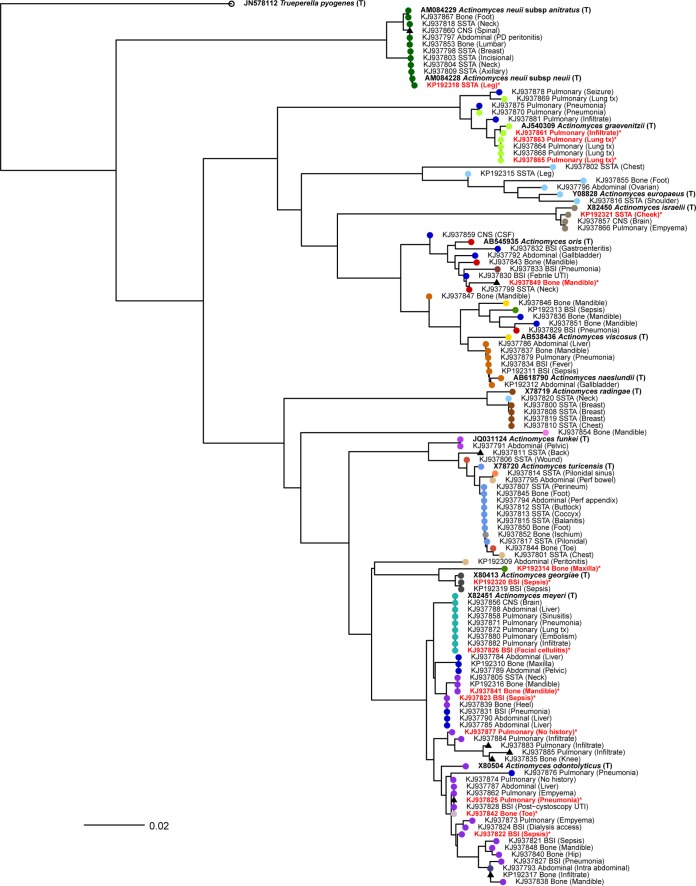

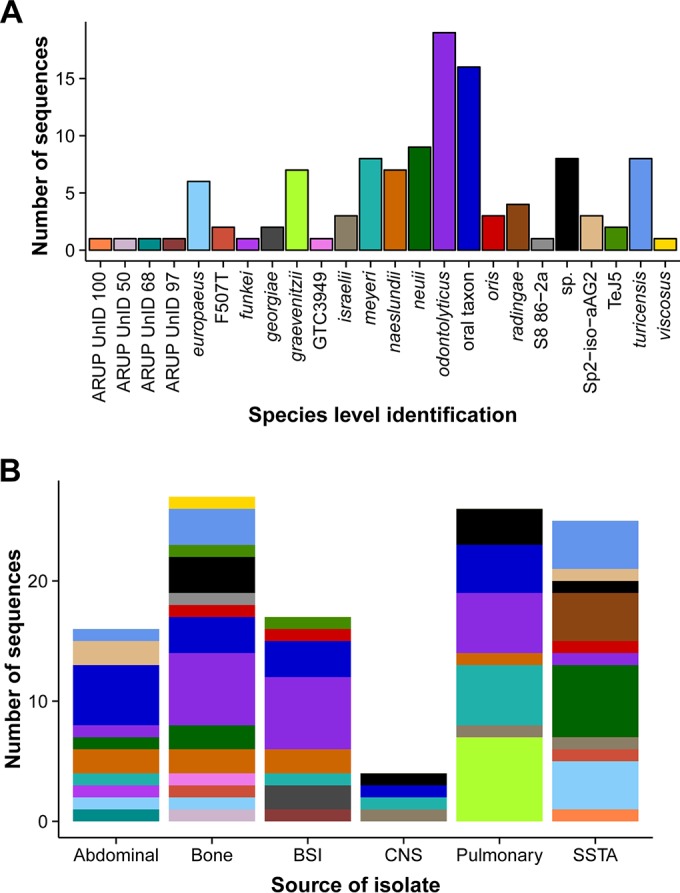

The species and source distributions of invasive infections primarily caused by Actinomyces spp. are outlined in Fig. 1A and B, respectively. The anatomical source category and basic clinical information from the reports are displayed as the tip labels in Fig. 2 alongside GenBank accession numbers. Anatomical sources included abdominal (n = 16, 14%), bone (n = 27, 23%), and bloodstream infections (BSIs) (n = 17, 15%) as well as central nervous system (CNS) (n = 4, 3%) and pulmonary sources (n = 26, 23%) and skin and soft tissue abscesses (SSTA) (n = 25, 22%). The SSTA infections were localized to the head or neck (6, 24%), the thoracic region (9, 36%), and the abdomen or lower body (10, 40%). All A. radingae infections (n = 4/4, 100%) occurred as SSTA infections of the thoracic region, and most A. neuii or A. neuii subsp. anitratus (6/9, 67%) presented as SSTA infections. Pulmonary infections included pneumonia, pulmonary infiltrates, pleural effusion, and empyema. A. graevenitzii was solely recovered from lung fluids or tissues and was not isolated from any other body site/source. Several yet to be named Actinomyces spp. (n = 7, 18%) were also isolated from pulmonary fluids. Osteomyelitis due to Actinomyces spp. most commonly occurred in one of the jaw bones (mandible and maxilla) (n = 14, 56%) or in the lower leg/foot (n = 11, 44%). Most bone infections were due to yet to be named Actinomyces spp. belonging to the oral taxons (n = 10, 40%) or A. odontolyticus (n = 6, 24%). Abdominal infections included intraabdominal abscesses, liver abscesses, and necrotizing fasciitis of the peritoneum. Only one isolate of A. funkei was recovered from an intraabdominal pelvic abscess. Central nervous system infections were caused by A. israelii (n = 1), A. meyeri (n = 2), and an unusual as yet to be named Actinomyces sp. (n = 2) isolated from brain and spinal abscesses.

FIG 1.

Distribution of Actinomyces by species and source. There were 115 Actinomyces isolates recovered from clinical samples between 2011 and 2014. All samples were identified using 16S rRNA sequencing. (A) The number of sequences identified from each species and the color legend for Fig. 1B and 2. (B) The distribution of species within each categorical source of infection, including abdominal, bone, bloodstream infection (BSI), central nervous system (CNS), pulmonary, and skin and soft tissue abscess (SSTA).

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Actinomyces 16S rRNA partial sequences. A neighbor-joining tree illustrates the phylogenetic relatedness of the sequences. The tips are color coded according to species as defined in Fig. 1A and are labeled by source with additional anatomical/clinical information in brackets. The tips displaying complete taxonomic identification and accession numbers in bold are type strain sequences (T) from the SILVA public database included for comparison. Discordant results from MALDI-TOF MS are labeled with red font and marked with an asterisk (*).The scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Seventeen patients primarily presented with a bloodstream infection (BSI) due to Actinomyces spp., of which 7 (44%) were children. The clinical diagnoses in children with BSIs included pneumonia (n = 2, 29%), SSTA (n = 3, 43%), severe tonsillitis (n = 1, 14%), and abdominal infection (n = 1, 14%). BSIs caused by Actinomyces spp. in adults mainly occurred due to either pneumonia or abdominal infections. Most BSIs were due to either A. odontolyticus or unusual as yet to be named Actinomyces spp. most closely related to oral taxon sequences.

Performance of MALDI-TOF MS for identification.

As shown in Table 1, MALDI-TOF MS identified 10/115 (9%) isolates to the genus, Actinomyces, and 47 (41%) to the correct species. Within these 47 correct species identifications, 12 provided correct species where the 16S identification was at the genus level only (n = 5) or the IDNS database identification provided a specific strain name and not a taxonomic species such as TeJ5 (n = 7). The 12 Vitek MS identifications included A. odontolyticus (n = 6), A. turicensis (n = 3), A. viscosus (n = 2), and A. neuii (n = 1). These were considered to be more accurate based on phylogenetic placement relative to the typed sequences (Fig. 2). In 43 (37%) cases, Vitek MS was unable to provide any identification despite being listed at the species level in the organism database. Vitek MS misidentified isolates in 15 (13%) of the total cases, with a reported excellent ID at a probability of 99%. These discordant identifications included Clostridium perfringens, Escherichia coli, Kocuria kristinae, Kytococcus sedentarius, Arcanobacterium haemolyticum, Streptococcus mitis, Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius, Paracoccus yeei, Staphylococcus warneri, and Cedecea neteri.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Actinomyces spp. identification using the expanded Vitek MS MALDI-TOF database and using 16S rRNA gene sequence identification

| 16S sequence identification | No. (%) correct to genus | No. (%) correct to species | No. (%) with discordant results | No. (%) with no result/ID | Total no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID to a specific sequencea | 4 (15) | 7 (23) | 2 (7) | 16 (55) | 29 (25) |

| Actinomyces sp. | 1 (12) | 5 (63) | 2 (25) | 8 (7) | |

| Actinomyces europaeus | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 6 (5) | ||

| Actinomyces funkei | 1 (100) | 1 (1) | |||

| Actinomyces georgiae | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (2) | ||

| Actinomyces graevenitzii | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | 7 (6) | ||

| Actinomyces israelii | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 3 (2) | ||

| Actinomyces meyeri | 4 (50) | 1 (12) | 3 (38) | 8 (7) | |

| Actinomyces naeslundii | 3 (43) | 1 (14) | 3 (43) | 7 (6) | |

| Actinomyces neuii | 6 (67) | 1 (1) | 2 (22) | 9 (7) | |

| Actinomyces odontolyticus | 1 (5) | 8 (42) | 4 (21) | 6 (32) | 19 (17) |

| Actinomyces oris | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 3 (2) | |

| Actinomyces radingae | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 4 (3) | ||

| Actinomyces turicensis | 8 (100) | 8 (7) | |||

| Actinomyces viscosus | 1 (100) | 1 (1) | |||

| Total | 10 (9) | 47 (41) | 15 (13) | 43 (37) | 115 |

Includes the following species according to 16S sequencing: Actinomyces F507T (2), Actinomyces ARUP UnID 100, 97, 68, and 50 (4), Actinomyces 606220/2008 (1), Actinomyces GTC3949 (1), Actinomyces oral taxon 169, 170, 171, 172, 175, 180, and A50 (15), Actinomyces S8 86-2a (1), Actinomyces sp2-iso-aAG2 (3), and Actinomyces TeJ5 (2).

Phylogenetic analysis of invasive Actinomyces spp.

Figure 2 illustrates the phylogenetic tree of all Actinomyces spp. isolated from our laboratory during the study period and additional publically available type strain sequences. Partial 16S rRNA sequences are displayed as circles and are color coded according to the species-level identification given by the SmartGene IDNS database. Sequences only identified to the genus level are shown as black triangles. Phylogenetic tree tips are labeled with GenBank accession number, source of infection, and clinical detail from the CLS database, while the reference strains are labeled in bold with accession number, genus, and species. The 15 discordant Vitek MS results are highlighted with red font and asterisk (*) symbols. Our phylogenetic results confirm the species identification by the IDNS database; the majority of species identifications match well to publically available type strain sequences. There are some clusters of mixed species, such as those sharing recent common ancestry with A. oris and A. viscosus, supporting previous reports of heterogeneity within these species (28–30). Interestingly, our data also illustrate how diverse the oral taxons are, as shown by the dark blue circles dispersed throughout the tree. In addition to the oral taxon classifications, there are other sequences that are not taxonomically named but that are considered species identifications in the database (i.e., F507T, GTC3949, SP2-iso-aAG2, and S8 86-2a) due to the growing number of molecular-based identification protocols and microbiome studies (31, 32).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study that documents the important role that a wide range of Actinomyces spp. plays in invasive infections on a population basis in a large health care region. In all cases, diagnosis of invasive infection was based on clinical and microbiological data from the site/source of infection, and the majority of isolates (110/115, 96%) were identified to the species level using 16S sequencing and identification with the IDNS SmartGene database. Although this study describes the recent clinical experience of a single health care region with a centralized regional microbiology laboratory, similar rates of invasive infections due to Actinomyces spp. would be expected to occur in other jurisdictions because actinomycosis is an endogenous infection. These organisms are part of the normal commensal flora on human mucosal surfaces, and opportunistic invasive infection only occurs when Actinomyces spp., either alone or as part of a polymicrobial process, invade into deeper tissues attributed with disruption of the host's mucosa (1, 2, 8). Usual inciting events for the development of actinomycosis include mechanical mucosal trauma due to injury, surgery, or placement of a foreign device.

A recent review on human Actinomyces infections by Könönen and Wade provides a thorough summary of the natural distribution of Actinomyces spp. in or on the body and Actinomyces spp. that have a predilection for causing invasive infections at specific body sites (2). Our study confirmed previous reports of the association of A. graevenitzii with pulmonary infections (33, 34) and of A. radingae with SSTA infections of the upper body associated with chest or breast abscesses (35). In our study, we found that A. odontolyticus was the most common and diverse cause of invasive actinomycosis, including intraabdominal abscesses, osteomyelitis, pulmonary infections, and sepsis.

Interestingly, isolates with 16S rRNA sequences most closely related to those identified in public databases as oral taxons from microbiome studies accounted for the second most abundant type of species. This group occurred in patients with diverse sources of infection. These isolates were not closely related as shown by the distribution of oral taxon sequences throughout the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). Further work to characterize these oral taxon isolates and their genomes will no doubt provide valuable information about this group and will likely lead to the identification of new species.

A growing number of case reports and literature reviews on actinomycosis have been published, suggesting greater attention is needed for invasive infections caused by Actinomyces spp. (2, 12, 36–38). Furthermore, large clinical and epidemiological studies using molecular identification methods for recovered Actinomyces spp. are clearly required to delineate the precise role of these commensal organisms as opportunistic human pathogens.

Our study shows that 16S rRNA sequencing remains the current gold standard method for definitive species-level identification. The Vitek MS system accurately identified approximately one-half of the isolates to the genus or species level. In a previous study by Garner et al. (15), Actinomyces isolates were correctly identified to the species level in 20/27 (74%) isolates. However, this study included only 3 species of Actinomyces. In our study, 18/36 (50%) of the same three species were correctly identified to the species level, but due to the small numbers, it is difficult to draw statistically significant conclusions. In addition, our study solely focuses on Actinomyces, including a more diverse sample population with half of the Actinomyces spp. that can only be identified to the genus level by 16S RNA sequencing.

In the other cases, an inaccurate identification or no result was provided by Myla version 3.1. Although MALDI-TOF MS may be used initially if validated for the identification of common species (e.g., A. europaeus, A. meyeri, A. neuii, A. odontolyticus, A. turicensis, and A. viscosus), other Gram-positive branching bacilli isolated as the sole or predominant pathogen from clinical samples from invasive tissues, sterile fluids, or blood cultures should be tested with molecular methods for a definitive identification if required. As a minimum, Actinomyces isolates recovered from suspected cases of actinomycosis (based on clinical and/or histological results) should be saved so that further microbiological characterization can be performed and the databases updated to improve accuracy for future testing.

In conclusion, this work demonstrates that a diverse number of Actinomyces spp. are recovered from sterile sites, and that half of these cannot be identified using our current MS platform. Accurate identification of invasive Actinomyces spp. may have clinical importance, as there is clustering of certain species within particular sites of infection. We also identify that serious infections are caused by a growing number of new and unusual Actinomyces spp. that have been identified primarily by molecular detection methods requiring future work to further characterize these species.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the microbiology laboratory technicians that perform all of the molecular and MALDI-TOF MS testing at Calgary Laboratory Services for all of their hard work and diligence.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wong VK, Turmezei TD, Weston VC. 2011. Actinomycosis. BMJ 343:d6099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Könönen E, Wade WG. 2015. Actinomyces and related organisms in human infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:419–442. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00100-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen T, Yu WH, Izard J, Baranova OV, Lakshmanan A, Dewhirst FE. 2010. The Human Oral Microbiome Database: a web accessible resource for investigating oral microbe taxonomic and genomic information. Database (Oxford). 2010:baq013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson H, Rybalka A, Moazzez R, Dewhirst FE, Wade WG. 25 September 2015. In-vitro culture of previously uncultured oral bacterial phylotypes. Appl Environ Microbiol doi: 10.1128/AEM.02156-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bose M, Ghosh R, Mukherjee K, Ghoshal L. 2014. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res 8:YD03–YD05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grice GC, Hafiz S. 1983. Actinomyces in the female genital tract. A preliminary report. Br J Vener Dis 59:317–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagiya H, Otsuka F. 2014. Actinomyces meyeri meningitis: the need for anaerobic cerebrospinal fluid cultures. Intern Med 53:67–71. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall V. 2008. Actinomyces—gathering evidence of human colonization and infection. Anaerobe 14:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EH, Degener JE, Welling GW, Veloo AC. 2011. Evaluation of the Vitek 2 ANC card for identification of clinical isolates of anaerobic bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 49:1745–1749. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02166-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller PH, Wiggs LS, Miller JM. 1995. Evaluation of API An-IDENT and RapID ANA II systems for identification of Actinomyces species from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 33:329–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stingu CS, Borgmann T, Rodloff AC, Vielkind P, Jentsch H, Schellenberger W, Eschrich K. 2015. Rapid identification of oral Actinomyces species cultivated from subgingival biofilm by MALDI-TOF-MS. J Oral Microbiol 7:26110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubourg G, Delord M, Gouriet F, Fournier PE, Drancourt M. 2015. Actinomyces gerencseriae hip prosthesis infection: a case report. J Med Case Rep 9:223. doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0704-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen HL. 2015. First report of Actinomyces europaeus bacteraemia result from a breast abscess in a 53-year-old man. New Microbes New Infect 7:21–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Hoecke F, Beuckelaers E, Lissens P, Boudewijns M. 2013. Actinomyces urogenitalis bacteremia and tubo-ovarian abscess after an in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedure. J Clin Microbiol 51:4252–4254. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02142-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garner O, Mochon A, Branda J, Burnham CA, Bythrow M, Ferraro M, Ginocchio C, Jennemann R, Manji R, Procop GW, Richter S, Rychert J, Sercia L, Westblade L, Lewinski M. 2014. Multi-centre evaluation of mass spectrometric identification of anaerobic bacteria using the Vitek MS system. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:335–339. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Interpretive criteria for identification of bacteria and fungi by DNA target sequencing; approved guideline. CLSI document MM18-A Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmon KE, Mirrett S, Reller LB, Petti CA. 2008. Genotypic diversity of anaerobic isolates from bloodstream infections. J Clin Microbiol 46:1596–1601. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02469-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simmon KE, Croft AC, Petti CA. 2006. Application of SmartGene IDNS software to partial 16S rRNA gene sequences for a diverse group of bacteria in a clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol 44:4400–4406. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01364-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glockner FO. 2013. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yilmaz P, Parfrey LW, Yarza P, Gerken J, Pruesse E, Quast C, Schweer T, Peplies J, Ludwig W, Glockner FO. 2014. The SILVA and “All-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D643–D648. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2014. MAFFT: iterative refinement and additional methods. Methods Mol Biol 1079:131–146. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-646-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson A. 2014. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 30:3276–3278. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T. 2009. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rambaut A. 2008. FigTree v1.3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. 2004. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20:289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kembel SW, Cowan PD, Helmus MR, Cornwell WK, Morlon H, Ackerly DD, Blomberg SP, Webb CO. 2010. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 26:1463–1464. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henssge U, Do T, Radford DR, Gilbert SC, Clark D, Beighton D. 2009. Emended description of Actinomyces naeslundii and descriptions of Actinomyces oris sp. nov. and Actinomyces johnsonii sp. nov., previously identified as Actinomyces naeslundii genospecies 1, 2 and WVA 963. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 59:509–516. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000950-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JL, Moore LV, Kaneko B, Moore WE. 1990. Actinomyces georgiae sp. nov., Actinomyces gerencseriae sp. nov., designation of two genospecies of Actinomyces naeslundii, and inclusion of A. naeslundii serotypes II and III and Actinomyces viscosus serotype II in A. naeslundii genospecies 2. Int J Syst Bacteriol 40:273–286. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-3-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henssge U, Do T, Gilbert SC, Cox S, Clark D, Wickstrom C, Ligtenberg AJ, Radford DR, Beighton D. 2011. Application of MLST and pilus gene sequence comparisons to investigate the population structures of Actinomyces naeslundii and Actinomyces oris. PLoS One 6:e21430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guss AM, Roeselers G, Newton IL, Young CR, Klepac-Ceraj V, Lory S, Cavanaugh CM. 2011. Phylogenetic and metabolic diversity of bacteria associated with cystic fibrosis. ISME J 5:20–29. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, Paster BJ, Tanner AC, Yu WH, Lakshmanan A, Wade WG. 2010. The human oral microbiome. J Bacteriol 192:5002–5017. doi: 10.1128/JB.00542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujita Y, Iikura M, Horio Y, Ohkusu K, Kobayashi N. 2012. Pulmonary Actinomyces graevenitzii infection presenting as organizing pneumonia diagnosed by PCR analysis. J Med Microbiol 61:1156–1158. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.040394-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gliga S, Devaux M, Gosset Woimant M, Mompoint D, Perronne C, Davido B. 2014. Actinomyces graevenitzii pulmonary abscess mimicking tuberculosis in a healthy young man. Can Respir J 21:e75–e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Attar KH, Waghorn D, Lyons M, Cunnick G. 2007. Rare species of Actinomyces as causative pathogens in breast abscess. Breast J 13:501–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyanova L, Kolarov R, Mateva L, Markovska R, Mitov I. 2015. Actinomycosis: a frequently forgotten disease. Future Microbiol 10:613–628. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bing AU, Loh SF, Morris T, Hughes H, Dixon JM, Helgason KO. 2015. Actinomyces species isolated from breast infections. J Clin Microbiol 53:3247–3255. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01030-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clancy U, Ronayne A, Prentice MB, Jackson A. 13 April 2015. Actinomyces meyeri brain abscess following dental extraction. BMJ Case Rep doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]