Abstract

To date, the exact targets and mechanism of action of curcumin, a natural product with anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties, remain elusive. Here we synthesized a cell permeable curcumin probe (Cur-P) with an alkyne moiety, which can be tagged with biotin for affinity enrichment, or with a fluorescent dye for visualization of the direct-binding protein targets of curcumin in situ. iTRAQTM quantitative proteomics approach was applied to distinguish the specific binding targets from the non-specific ones. In total, 197 proteins were confidently identified as curcumin binding targets from HCT116 colon cancer cell line. Gene Ontology analysis showed that the targets are broadly distributed and enriched in the nucleus, mitochondria and plasma membrane, and they are involved in various biological functions including metabolic process, regulation, response to stimulus and cellular process. Ingenuity Pathway AnalysisTM (IPA) suggested that curcumin may exert its anticancer effects over multiple critical biological pathways including the EIF2, eIF4/p70S6K, mTOR signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction pathways. Functional validations confirmed that curcumin downregulates cellular protein synthesis, and induces autophagy, lysosomal activation and increased ROS production, thus leading to cell death.

The study of naturally-derived compounds holds great potential for therapeutic and medicinal applications. One example is that of the polyphenolic compound curcumin, an active component of turmeric (Curcuma longa) which has long been a staple of Asian cuisines as well as a traditional remedy to a wide range of illnesses1. It is now understood that curcumin exhibits highly pleiotropic effects including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory and anti-infective properties2. Given its dietary role, it is also well-tolerated and safe to humans at dosages of up to 12 grams per day1,3. These characteristics have led to recent attention on the potential of curcumin as a novel anti-cancer therapy, with over 20 ongoing clinical trials for various cancers1,4. The pleiotropic nature of curcumin can be attributed to its ability to interact with a large number of cellular targets involved in multiple pathways2. It is therefore of great interest to identify the binding targets of curcumin in cancer cells. While reports have been made regarding potential targets of curcumin, the approaches have generally been restricted in scope or otherwise limited in terms of their applicability to living cells5. Recently, clickable small molecule probes have been used in identifying the targets of many bio-active natural products or drugs6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. In this study, we comprehensively identified in situ the specific and direct protein binding targets of curcumin in a colon cancer cell line (HCT116), via the synthesis of a cell-permeable clickable curcumin probe (Cur-P) combined with quantitative chemical proteomics methods (Fig. 1a)11,12. Functional validations were subsequently carried out for key pathways identified as targets of curcumin, confirming the role of curcumin in downregulation of cellular protein synthesis, as well as the induction of autophagy, lysosomal activation and increased ROS production.

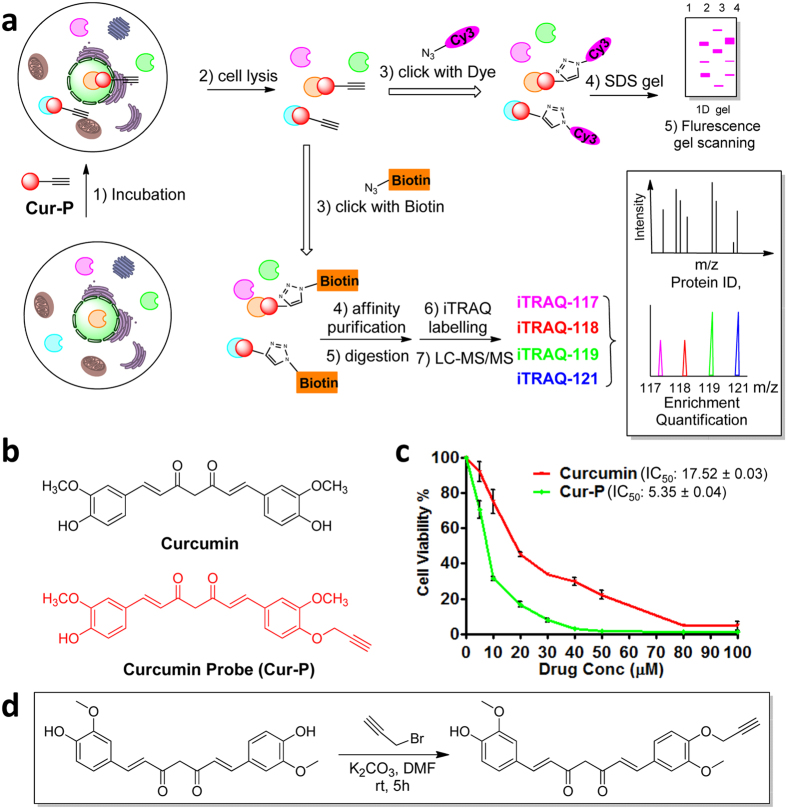

Figure 1. Overview of quantitative chemical proteomics approach for identifying the targets of curcumin.

(a) Overall workflow for in situ profiling of potential curcumin targets in live cells. (b) The structure of curcumin and curcumin-based probe (Cur-P). (c) Dose-dependent inhibition of HCT116 cell proliferation by curcumin and Cur-P. (d) Synthetic scheme of Cur-P. Error bars represent s.d. in three independent replicates in (c).

Results

Chemical synthesis of curcumin-based activity probe (Cur-P)

Ideally, the design of the curcumin based probe must retain the active moiety of this natural product. Previous studies showed that the α, β-unsaturated ketone group of curcumin is critical for its biological activity3,4. Structure-activity relationship studies suggested that the derivative of curcumin at the hydroxyl group did not affect the active moiety of the drug1,14. To profile and identify the direct targets of curcumin, we introduced an alkyne group at the hydroxyl group position of curcumin to synthesize an activity-based probe, which enables the subsequent linking with a fluorescent dye or biotin (Fig. 1b,d, for synthesis, see supplementary information). Briefly, the curcumin probe (Cur-P) was readily synthesized by mono-alkylation of curcumin by propargyl bromide and its structure was verified by H-NMR, C-NMR and high resolution mass spectrometry. We have confirmed that the probe still retains the anti-cancer activities and Cur-P is even more potent than curcumin in HCT 116 colon cancer cells using the crystal violet assay (Fig. 1c). This is consistent with previous study which showed that the alkylation of ortho-phenolic OH group in curcumin and its derivatives can increase its anti-cancer activity14. However, all the OH modified derivatives share the same pharmacophore (α, β-unsaturated ketone group) which imply they have same mode of action15,16. To further confirm that Cur-P possesses similar biological activity as the parent compound, , the cells were treated with curcumin or Cur-P in parallel (vide infra) in the aftermentioned functional assays (ROS, Lysotracker staining and autophagy flux assay). No significant differences were observed between the drug and the probe (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fluorescence labelling profiling of curcumin binding proteins

To visualize the native cellular protein targets of curcumin, the labeling concentration of Cur-P was firstly optimized. Live HCT 116 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Cur-P for 4 h before lysis. The lysate was then reacted with Rhodamine B-azide through click chemistry followed by SDS-PAGE and fluorescence scanning. The results showed a dose-dependent increase in fluorescence labeling and a satisfactory level of Cur-P labeling can be achieved with 30 μM of Cur-P (Supplementary Fig. S2), which was chosen for subsequent in situ gel-based fluorescence labeling (Fig. 2a) and pull-down experiments. To examine whether the Cur-P binds to similar protein targets in HCT 116 cell lines, we have also pre-treated the cell lysate with curcumin and then treated it with Cur-P. Curcumin pre-treatment essentially attenuated the probe labeling fluorescence signals, suggesting that Cur-P largely targets the same proteins as curcumin (Supplementary Fig. S3).

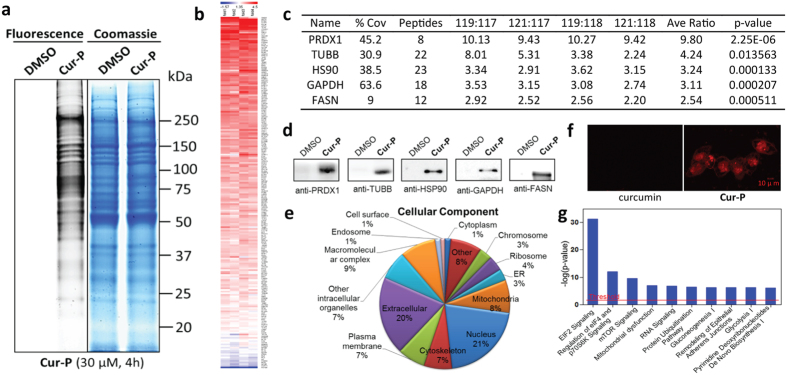

Figure 2. Quantitative chemical proteomics reveals curcumin-specific target proteins and involved pathways.

(a) Left, fluorescence images of SDS-PAGE gel lanes of Cur-P (30 μM) – labeled HCT116 cells as well as the control cells treated with DMSO; Right, the same lanes stained with coomassie blue. (b) Heat map of the enrichment ratios of potential curcumin targets fulfilled the statistical requirement. An enlarged figure is shown in Supplementary Fig. S4 (c) The representative proteins identified by Cur-P in HCT116 cells (Sorted by average enrichment ratios). (d) Western-blotting validation of the selected Cur-P targets. (e) GO analysis of cellular localization of the Cur-P targets. (f) Cellular imaging of HCT116 cells incubated with 2 μM Cur-P. Cells were treated with Cur-P (2 μM) for 12 h, and then fixed and permeabilized for the click chemistry reaction. The fluorescence images were acquired with confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. (g) Top canonical pathways that the curcumin protein targets are significantly over-represented.

Identification of curcumin targets by quantitative chemical proteomics

Next, iTRAQ-based quantitative chemical proteomics was performed to identify the targets of curcumin using Cur-P. To cope with the biological and experimental variations, two curcumin probes- and two DMSO-treated samples were analyzed as biological replicates. HCT116 cells were incubated with 30 μM Cur-P or DMSO (negative control) for 4 h before lysis. The lysate was then reacted with the biotin azide tag, followed by affinity enrichment using avidin beads. The beads were thoroughly washed and on-beads trypsin digestion was conducted. The derived peptides were reacted with iTRAQ reagents (control samples were labeled with 117 or 118; Cur-P treated samples were labeled with 119 or 121). The labeled samples were then pooled together and analyzed by LC-MS/MS to identify and quantify the target proteins. For specific protein targets, the iTRAQ reporter ions 119 and 121 have significantly higher intensities than 117 and 118, whereas for the non-specific binding and endogenously biotinylated proteins, the reporter intensities are similar (Fig. 1a). In our study, a total of 370 proteins were successfully identified and quantified using iTRAQ-based quantification coupled with activity-based proteome profiling (ABPP) (Supplementary Table 1). iTRAQ ratios of each identified protein were subjected to statistical test and only proteins identified with at least two peptides and have p- values less than 0.05 were considered statistically reliable hits, which resulted in a list of 212 proteins (Supplementary Table 2). The distribution of the enrichment ratios of these proteins is presented as a colored heat map in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. S4. To differentiate specific binding targets from non-specific ones, we then applied a highly stringent cut-off threshold (iTRAQ ratio ≥2.5) to minimize potential false-positive targets. Consequently, we have identified 197 proteins as the specific targets of curcumin (Supplementary Table 3).

To further validate the identified proteins as the direct binding targets of curcumin, five representative proteins with enrichment ratios from 2.5 to 10 in our list were subjected to pull-down experiments with Cur-P, followed by immunoblotting with their respective antibodies (Fig. 2c,d). Results unequivocally confirmed the direct interaction between Cur-P and the protein targets.

Pathway analysis of targets of curcumin

Subsequently, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the curcumin targets. It was shown that the targets are broadly distributed in different parts of the cell, and especially enriched in the nucleus, mitochondria and plasma membrane (Fig. 2e). To confirm this, Cur-P-treated cells were examined with confocal microscopy to visualize the cellular distribution of curcumin targets (Fig. 2f). HCT116 cells were treated with Cur-P, fixed by paraformaldehyde and permeabilized by Triton X-100, and then conjugated with Rhodamine B-azide by click chemistry before confocal fluorescence imaging. Cur-P-treated cells showed high levels of fluorescence in the cell membrane and nucleus, whereas no fluorescence signal was observed in the control cells treated with DMSO (Fig. 2f). Thus, our imaging results are consistent with the GO analysis of our curcumin targets.

GO analysis also showed that the curcumin targets are involved in various biological functions including metabolic process, regulation, response to stimulus and cellular process, etc. (Supplementary Fig. S5). Ingenuity Pathway AnalysisTM (IPA) suggested that curcumin may exert its anticancer effects over multiple critical biological pathways including the EIF2, eIF4/p70S6K, mTOR signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction pathways (Fig. 2g). Other IPA analysis results were shown in Supplementary Fig. S6.

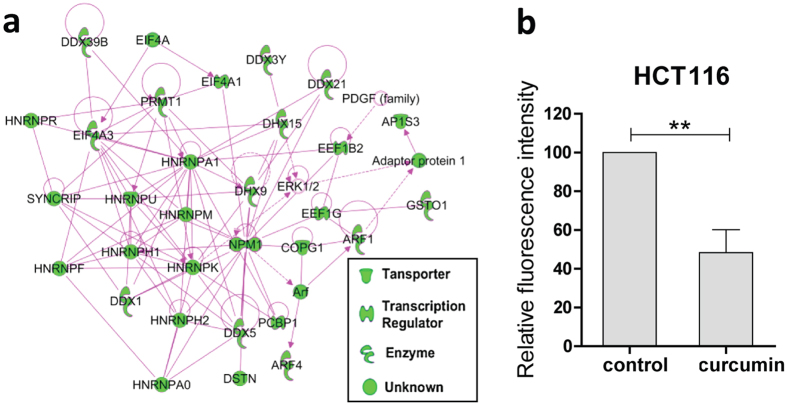

Inhibition of de novo protein synthesis by curcumin

Our pathway analysis highlighted elF2 signaling, regulation of elF4 and p70S6K signaling as well as mTOR signaling as the top three canonical pathways that the curcumin targets are involved in, suggesting that the cellular protein synthesis may be affected by curcumin (Figs 2g and 3a). Therefore, we first examined the changes of the protein synthesis levels of HCT116 cells upon curcumin treatment. We used azidohomoalanine (AHA), an artificial amino acid that can be incorporated into the newly synthesized proteins to monitor the level of protein synthesis17. The incorporated AHAs were then labeled with a fluorescence tag via click chemistry and the fluorescence intensity of the cells was measured by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 3b, curcumin (5 μM) treatment for 16 h caused a 50% reduction of the AHA signal intensity in HCT116 cells, indicating that curcumin can potently inhibit de novo protein synthesis.

Figure 3. Curcumin inhibited de novo protein synthesis.

(a) Network of curcumin target proteins (green nodes) affecting protein synthesis, revealed by Ingenuity Pathway AnalysisTM (IPA). (b) Curcumin treatment (5 μM, 16 h) significantly reduced the level of newly synthesized proteins in HCT116 cells. Data shown are mean ± SD from three independent experiments; **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

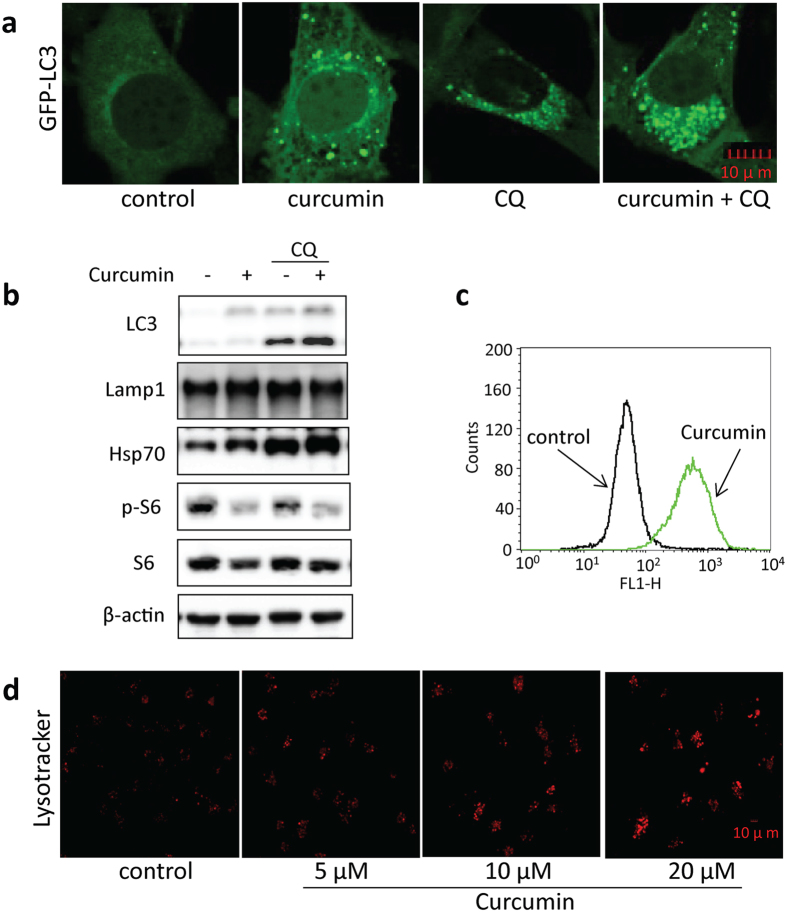

Induction of autophagy by curcumin

As reflected in our pathway analysis, mTOR pathway was involved in curcumin-treated cells. mTOR (Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin) is a serine/threonine protein kinase that regulates multiple biological processes including cell growth, cell proliferation, cell motility, cell survival, and protein synthesis, etc18,19,20. Inhibition of protein synthesis by curcumin implies that mTOR signaling pathway may be inhibited. This is in agreement with previous studies showing that curcumin can inhibit phosphorylation of mTOR and its downstream effectors phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), and disrupt the mTOR complex21,22,23,24. mTOR has been well known to negatively regulate autophagy via suppressing the ULK1 (the mammalian homolog of yeast Atg1) complex, which consists of ULK1, FIP200, ATG13 and ATG10125,26. Therefore, we hypothesized that curcumin treatment may enhance autophagy of the cells. To verify this hypothesis, the changes in mTOR activity and autophagy markers were examined by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 4a,b, curcumin treatment increased autophagy flux level in HCT116 and MEF cells, consistent with previous reports27,28,29. Western blot detection of increased autophagy marker LC3 level further confirmed curcumin as an autophagy inducer. In addition, the inhibitory effect of curcumin on mTOR activity was also verified by the suppression of S6 phosphorylation (Ser235/236), a downstream protein substrate of mTOR (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Curcumin induced autophagy and activated lysosomal function in cells.

(a) Curcumin increased GFP-LC3 puncta in MEF cells. MEF cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 were treated with 20 μM curcumin for 12 h with or without 25 μM chloroquine. The GFP-LC3 distribution pattern was revealed with a confocal microscope. Scale bars, 10 μm. (b) HCT116 cells were treated with 20 μM curcumin with or without 25 μM chloroquine, followed by western-blot analyses of the cell lysates. β-actin was used as the loading control. (c) Curcumin increases ROS levels in HCT116 cells. Cells were treated with 20 μM curcumin for 12 h and then stained with DCFH-DA. The fluorescence signals were monitored with flow cytometry. (d) Dose-dependent increase of lysosomal acidification in HCT116 cells upon curcumin treatment. HCT116 cells were treated with curcumin (5, 10 or 20 μM) for 12 h followed by staining with LysoTracker Red DND-99 (50 nM) for 15 min. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Our pathway analysis also highlighted the mitochondrial dysfunction which usually accompanied by the change of the ROS level. Given the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in autophagosome development and autolysosomal degradation, we further measured changes in ROS production following curcumin treatment. As indicated by Fig. 4c, curcumin increased ROS levels in HCT116 cells, consistent with previous reports by Lee et al.30 and suggesting that effects on ROS production could contribute to autophagic induction by curcumin.

At the late stage of autophagy, autophagosomes are fused with lysosome to form autolysosome for degradation. Under starvation condition or upon mTOR inhibition, lysosome is activated31. mTOR inhibition in curcumin-treated cells has been previously reported21,22,23,24, and confirmed by our pathway analysis and de novo protein synthesis inhibition assay. Here, we also determined changes in HCT116 cells at lysosomal level. As shown in Fig. 4d, LysoTracker staining showed a significant increase of cellular fluorescence intensity in HCT116 cells treated with different concentrations of curcumin, indicating enhanced acidification and lysosomal activation. In addition, we also showed that curcumin increased lysosomal membrane protein expression in HCT116 cells, such as Lamp132 and Hsp7033 (Fig. 4b). Taken together, these results suggested that curcumin also acts by lysosomal activation to induce autophagy.

Discussion

The mechanism of action (MOA) of curcumin has been widely studied. It has been reported to target multiple proteins such as transcription factors, kinases and cytokines, and affect multiple pathways/biological processes such as inhibition of protein synthesis, induction of autophagy and apoptosis, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant processes, etc.1,4,34,35. However, most of the prior reports focused on the study of individual pathway/process, thus would not provide a full picture of the MOA of curcumin. Comparative proteomics profiling approaches have been applied to examine the curcumin treated samples versus the controls and multiple proteins with abundance changes were identified. Although these studies provided a comprehensive overview of curcumin induced cellular changes, they could not distinguish primary alterations from the secondary effects36,37,38,39. Identification of direct binding targets of curcumin, on the other hand, provides clues on the initial and most important changes that are caused by the compound. Previously, curcumin has be tagged with biotin, or immobilized to a solid phase and then reacted with cell/tissue lysates5. The protein targets were then affinity purified, followed by gel-based separation and mass spectrometric identification. However, such in vitro studies may not truly reflect the actual drug-target interaction in vivo. Also, gel-based approaches were restricted by a limited dynamic range, thus only the most abundant protein targets were identified. Therefore, the results obtained were not comprehensive enough and no pathway and functional validation were conducted in those studies. In this context, we introduced a tiny alkyne group to curcumin to create an activity-based probe. Unlike the bulky biotin tag, the small alkyne group does not affect the compound’s ability to penetrate the plasma membrane thus the probe can be used to target the proteins in vivo. After cell lysis, a biotin tag was then conjugated to the protein targets using click chemistry, which facilitates affinity purification of the targets. LC-MS was used for the protein target identification, which has wider dynamic range compared to gel-based approaches, leading to a dramatic increase of the total number of curcumin targets identified. In addition, iTRAQ quantitative proteomics approach was applied to filter out the non-specific binding proteins and endogenously biotinylated proteins. This enhanced the reliability of the curcumin targets that we identified. In total, 197 proteins were confidently identified as curcumin binding targets in our study. Several pathways that the curcumin targets are involved in were validated, including protein synthesis inhibition, autophagy and ROS induction. These cellular changes upon curcumin treatment are consistent with previous literature, confirming the reliability of our curcumin target dataset. Our results thus provided a comprehensive overview into the MOA of curcumin for its anti-cancer therapeutic effects, which will be beneficial for its future clinical application. The stringent experimental conditions we set up in this study identified curcumin targets with high confidence, but excluded the possibility of identifying any potential non-covalent binding targets. To overcome this limitation, we are developing a new curcumin probe with a photo cross-linking group which can be used to capture the transient curcumin-protein interaction. It will also be interesting to determine the roles of individual covalent binding target in curcumin-mediated cancer cell killing in future. Our current approach can also be applied to study the curcumin targets in normal cell lines in parallel with the cancer cells and compared with quantitative proteomics, so that we can further fish out most critical targets for curcumin’s anti-cancer property. The studies can also be extended to animal models in future. Nevertheless, as our results showed that curcumin can covalently bind to hundreds of protein targets, further investigation would be required before seriously considering it as a potential drug candidate.

Methods

In Situ fluorescence labeling experiments

HCT116 cells were cultured in six-well plates until 80 – 90% confluence was reached. Then the cells were washed thrice with PBS. Cur-P (5–60 μM) in 2 ml of medium with a final DMSO concentration of 1% was added, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 4 h. Control treatment was done with the same volume of medium containing 1% DMSO. After treatment, the cells were washed with PBS and trypsinized to detach from the plate. The cells were pelleted, resuspended in PBS, washed, and subjected to sonication in 100 μl of PBS to lyse the cells. Centrifugation (10,000 rpm; 45 min) was applied to remove the insoluble fraction from the cell lysate. Bradford assay was used to determine the protein concentrations of the supernatants. Equal amounts (50 μg) of the extracted proteins were then subjected to fluorescence labeling. The click reaction was done by adding Rhodamine B -azide (10 μM), TCEP (1 mM), TBTA (100 μM), and CuSO4 (1 mM) to the lysate, followed by 2 h-incubation at room temperature. The labeled proteins were then acetone-precipitated and air-dried. The samples were then solubilized with 100 μl of 1× SDS loading buffer. Fifty microliter of sample was separated with 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel. Typhoon 9410 laser scanner (GE Healthcare) was used to obtain the gel images, which were analyzed by Image Quant software.

Curcumin target identification using quantitative chemical proteomics

In the subsequent target identification, two biological duplicates of Cur-P-treated samples and two control samples treated with DMSO were affinity-enriched and parallel digested and then labeled with iTRAQ reagents (119, 121, 117 and 118 respectively), followed by LC-MS/MS to identify and quantify the protein targets.

Briefly, the HCT116 cells were cultured in 150 mm culture dish until 80% confluence was reached. After removal of culture medium and washing twice with PBS, Cur-P (30 μM) in 20 ml of medium with a final DMSO concentration of 1% was added to the cells, followed by incubation for 4 h. Control treatments were performed with culture medium containing 1% DMSO. The media were discarded after treatment, and then the cells were subjected to PBS wash and trypsinization to detach from the plate. The cells were pelleted, washed with PBS, and sonicated to lyse in PBS. The insoluble fraction was removed by centrifugation (10,000 rpm; 45 min), and then the protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by Bradford assay. Equal amounts (4 mg) of the extracted proteins (two Cur-P-treated and two DMSO-treated samples) were conjugated with the biotin tags separately via click chemistry, by adding biotin-azide (10 μM), TCEP (1 mM), TBTA (100 μM) and CuSO4 (1 mM) followed by 4 h shaking. The reacted proteins were then acetone-precipitated and air-dried. The pellet was re-solubilized with 1 ml of PBS containing 0.1% SDS and then added 40 μl of Streptavidin beads, followed by 2 h-incubation at room temperature with gentle mixing.

On-beads tryptic digestion

After washing three-time each with 1% SDS, 6M urea and PBS, 150 μL 20 mM Triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) and 2 μL TCEP (100 mM stock solution) were added to re-suspend the beads, followed by incubation at 60 °C for 50 min. After addition of 1 μL MMTS (200 mM stock solution), the samples were kept at room temperature for 20 min. Trypsin (10 ng/μL) was then added and the samples were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h.

iTRAQ labeling of the tryptic peptides

Labeling was performed using iTRAQ Reagent-8Plex reagent (SCIEX; Foster City, CA). The two negative controls and the two Cur-P pull-down samples were labeled with reagent 117, 118, 119 and 121 respectively. Briefly, after drying and reconstituting with 30 μL 0.5 M TEAB, the digested peptides were reacted with respective iTRAQ reagents for 3 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the labeled samples were pooled together and subjected to strong cation exchange and desalting. After desalting, the iTRAQ labeled peptide sample was dried and re-dissolved in 80 μl of 2% acetonitrile (ACN) containing 0.05% formic acid (FA).

Nano LC−ESI-MS

For LC-MS/MS procedures, an Eksigent nanoLC Ultra and ChiPLC-nanoflex (Eksigent, Dublin, CA) system was used to separate iTRAQ labeled peptides with Trap-Elute configuration. Four microliter of the sample from the above section was injected into the system. The sizes of the trap and analytical columns are 200 μm × 0.5 mm and 75 μm × 150 mm respectively, and both were packed with ChromXP C18-CL, 3 μm (Eksigent, Germany). Mobile phase A was composed of 2% ACN and 0.1% FA, and mobile phase B was composed of 98% ACN and 0.1% FA. The flow rate was 300 nL/min. The following gradients were applied for the peptide separation: 5–12% B in 20 min followed by 12–30% B in 90 min, and then 30–90% B in 2 min. The columns were regenerated with 90% B for 5 min and 90–5% B for 3 min, and equilibrated with 5% B for 13 min40.

A TripleTOF 5600 system (SCIEX) was used to acquire the MS and MS/MS spectra. High resolution mode (>30000) was used to acquire the MS spectra at 400–1250 m/z range and the signals were accumulated for 250 ms for each spectrum. High sensitivity mode (resolution >15000) was used to acquire the MS/MS spectra. The “adjust CE when using iTRAQ Reagent” function was turned on. For each duty cycle, up to 20 precursors were chosen from the MS spectrum for MS/MS analysis/and the signals were accumulated for a minimum of 100 ms per spectrum. The dynamic exclusion time was set at 15 s.

Protein identification and quantification

ProteinPilot™ 4.5 (SCIEX) was applied to protein identification and iTRAQ quantification, using SwissProt (2013_09, total 540958 sequences) as the database. The search parameter settings were: Cysteine alkylation with MMTS; Trypsin Digestion; TripleTOF 5600; Biological modifications. The identified proteins were grouped using the ProGroup algorithm to eliminate the redundancy. A decoy database search strategy was applied to determine the false discovery rate (FDR). Unused score >1.3 (corresponding to a protein confidence interval >95%) was applied as the cutoff threshold for protein identification, with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.33%.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, J. et al. In situ Proteomic Profiling of Curcumin Targets in HCT116 Colon Cancer Cell Line. Sci. Rep. 6, 22146; doi: 10.1038/srep22146 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.Z. is supported by NUS research scholarship. We thank Dr. Liqian Gao and Dr. Siewli Lai for critical review of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.W. designed and performed the experiments, wrote the manuscript. J.Z. performed the functional experiments and wrote the manuscript. C.J.Z. assisted the design of the probe. Y.K.W. assisted the data analysis. T.K.L. assisted the proteomics experiments. Z.C.H. assisted the pathway analysis and supported this project. B.L. assisted the probe design and supported this project. S.R.S. supported and supervised this project. H.M.S supported and supervised this project. Q.L. supported, supervised this project and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Salem M., Rohani S. & Gillies E. R. Curcumin, a promising anti-cancer therapeutic: a review of its chemical properties, bioactivity and approaches to cancer cell delivery. RSC Adv. 4, 10815–10829 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. C. et al. Multitargeting by curcumin as revealed by molecular interaction studies. Nat. Prod. Rep. 28, 1937–1955 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. C., Kismali G. & Aggarwal B. B. Curcumin, a component of turmeric: From farm to pharmacy. BioFactors 39, 2–13 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basnet P. & Skalko-Basnet N. Curcumin: An anti-inflammatory molecule from a curry spice on the path to cancer treatment. Molecules 16, 4567–4598 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo L. S. et al. Binding partners for curcumin in human schwannoma cells: Biologic Implications. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 21, 932–939 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Target identification of natural and traditional medicines with quantitative chemical proteomics approaches. Pharmacol. Ther. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.01.010 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalesh K. a., Clulow J. a. & Tate E. W. Target profiling of zerumbone using a novel cell-permeable clickable probe and quantitative chemical proteomics. Chem. Commun. 51, 5497–5500 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Li L., Uttamchandani M. & Yao S. Q. A tuned affinity-based staurosporine probe for in situ profiling of protein kinases. Chem. Commun. 50, 2851–2853 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Cheng X., Sze S. K. & Yao S. Q. Proteome profiling reveals potential cellular targets of staurosporine using a clickable cell-permeable probe. Chem. Commun. 47, 11306 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P.-Y., Wang M., He C. Y. & Yao S. Q. Proteomic profiling and potential cellular target identification of K11777, a clinical cysteine protease inhibitor, in Trypanosoma brucei. Chem. Commun. 48, 835 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. A Quantitative Chemical Proteomics Approach to Profile the Specific Cellular Targets of Andrographolide, a Promising Anticancer Agent That Suppresses Tumor Metastasis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 876–886 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Mapping sites of aspirin-induced acetylations in live cells by quantitative acid-cleavable activity-based protein profiling (QA-ABPP). Sci. Rep. 5, 7896 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Haem-activated Promiscuous Targeting of Artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Commun. 6, 10111 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciochina R., Savella C., Cote B., Chang D. & Rao D. Synthesis and characterization of new curcumin derivatives as potential chemotherapeutic and antioxidant agents. Drug Dev. Res. 75, 88–96 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W. et al. Synthesis of monofunctional curcumin derivatives, clicked curcumin dimer, and a PAMAM dendrimer curcumin conjugate for therapeutic applications. Org. Lett. 9, 5461–5464 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Droumaguet B. et al. Versatile and efficient targeting using a single nanoparticulate platform: Application to cancer and alzheimer’s disease. ACS Nano 6, 5866–5879 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Wang J., Ng S., Lin Q. & Shen H. M. Development of a novel method for quantification of autophagic protein degradation by AHA labeling. Autophagy 10, 901–912 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoncu R., Efeyan A. & Sabatini D. M. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 21–35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K. & Guan K.-L. Complexity of the TOR signaling network. Trends Cell Biol. 16, 206–212 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., Peterson T. R. & Sabatini D. M. Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Mol. Cell 40, 310–322 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers C. S. et al. Curcumin disrupts the mammalian target of rapamycin-raptor complex. Cancer Res. 69, 1000–1008 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. M. et al. Curcumin inhibits proliferation of colorectal carcinoma by modulating Akt/mTOR signaling. Anticancer Res. 29, 3185–3190 (2009). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. et al. Curcumin Dually Inhibits Both Mammalian Target of Rapamycin and Nuclear Factor- B Pathways through a Crossed Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt/I B Kinase Complex Signaling Axis in Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 106–118 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Shen G., Khor T. O., Kim J.-H. & Kong A.-N. T. Curcumin inhibits Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling through protein phosphatase-dependent mechanism. Mol. Cancer Ther. 7, 2609–2620 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 132–139 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa N. et al. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 Association with the ULK1 – Atg13 – FIP200 Complex Required for Autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 20, 1981–1991 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J. et al. Curcumin induces autophagy to protect vascular endothelial cell survival from oxidative stress damage. Autophagy 8, 812–825 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao K. et al. Curcumin induces autophagy via activating the AMPK signaling pathway in lung adenocarcinoma cells. J Pharmacol Sci 123, 102–109 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi Y., Izumi Y., Asakura K., Hayashi Y. & Nomori H. Curcumin induces autophagy in ACC-MESO-1 cells. Phyther. Res. 26, 1779–1783 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. J., Kim N. Y., Suh Y. A. & Lee C. Involvement of ROS in curcumin-induced autophagic cell death. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 15, 1–7 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C. et al. A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. EMBO J. 31, 1095–1108 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbacher N., Bastholm L., Kirkegaard-Sorensen T., Rafn B., Bottzauw T., Nielsen C., Weber E., Shirasawa S. & Kallunki T. J. M. Sensitization to the lysosomal cell death pathway by oncogene-induced down-regulation of lysosome-associated membrane proteins 1 and 2. Cancer Res 68, 6223–6233 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylandsted J. et al. Heat shock protein 70 promotes cell survival by inhibiting lysosomal membrane permeabilization. J. Exp. Med. 200, 425–435 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel A., Kunnumakkara A. B. & Aggarwal B. B. Curcumin as ‘Curecumin’: From kitchen to clinic. Biochem. Pharmacol. 75, 787–809 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam M. et al. The Multifaceted Role of Curcumin in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Molecules 20, 2728–2769 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden K. et al. Proteomics-based approach to elucidate the mechanism of antitumor effect of curcumin in cervical cancer. Prostaglandins. Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 80, 9–18 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firouzi Z. et al. Proteomics screening of molecular targets of curcumin in mouse brain. Life Sci. 98, 12–17 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D.-J. et al. Proteomic analysis identifies proteins associated with curcumin-enhancing efficacy of irinotecan-induced apoptosis of colorectal cancer LOVO cell. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 7, 1–15 (2014). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.-E., Lu D.-Z., Lin T.-Q., Wang Y.-L. & Wo X.-D. The Effects of Curcumin on the Proteome of L02 Cells. Biomed. Eng. Biotechnol. (iCBEB), 2012 Int. Conf. 593–596 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Dramatic improvement of proteomic analysis of zebrafish liver tumor by effective protein extraction with sodium deoxycholate and heat denaturation. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2015, 763969 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.