Abstract

The natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) receptor and its ligands are important mediators of immune responses to tumors. NKG2D ligands are overexpressed in several malignant tumor types; however, the prognostic value of these ligands is unclear. Here, we aimed to elucidate the role of NKG2D ligands in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EHCC). We therefore investigated the expression of the NKG2D receptor and its ligands MHC class I chain‐related proteins A and B (MICA/B), unique long 16 binding protein (ULBP) 1, and ULBP2/5/6 in resected specimens from 82 patients with EHCC. All NKG2D ligands were highly expressed in EHCC. High expression of MICA/B or ULBP2/5/6 correlated with overall and disease‐free survival. In contrast, high expression of ULBP1 was significantly associated with improved overall survival, but not disease‐free survival. Concurrent high expression of multiple NKG2D ligands revealed significantly better overall and disease‐free survival than that observed with the overexpression of any one NKG2D ligand. Co‐expression of multiple NKG2D ligands was an independent prognostic indicator of improved survival. Furthermore, co‐overexpression of multiple NKG2D ligands was significantly correlated with high expression of the NKG2D receptor. Inhibiting interactions between multiple NKG2D ligands and the NKG2D receptor might be a promising approach for controlling cancer progression and improving patient prognosis in EHCC.

Keywords: Cholangiocarcinoma, immunohistochemistry, MHC class I chain‐related proteins A and B, natural killer group 2 member D, unique long 16 binding protein

Cholangiocarcinoma is a malignant cancer that originates from epithelial cells in bile ducts.1, 2 It is classified as intrahepatic or extrahepatic, and EHCC is subcategorized into perihilar and distal forms.3, 4 Although EHCC is relatively uncommon in North America and Europe, its incidence and mortality rates continue to rise worldwide.5, 6 This is especially true in Japan, where the annual mortality due to EHCC was approximately 12 000 in 2013.7 There is no curative treatment for cholangiocarcinoma except surgical resection and, despite recent advances in surgical techniques, recurrence occurs in most patients even after resection. Regrettably, post‐resection 5‐year survival rates are only 20–30%.8 Therefore, the identification of new therapeutic targets and biomarkers is critical for improving outcomes in patients with cholangiocarcinoma.

We previously reported that epithelial–mesenchymal transition‐related factors, such as epithelial/neural‐cadherin and forkhead box protein C2, were correlated with the prognosis and progression of EHCC.9, 10 Due to recent advancements in cancer immunotherapeutics, the editors of Science named cancer immunotherapy as the Breakthrough of the Year in 2013.11 In particular, the immune checkpoint blockade approach involving the use of the anti‐cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen 4 antibody and the anti‐PD‐1 antibody were significant recent developments. The US FDA has approved ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, and nivolumab for the treatment of metastatic melanoma, and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency in Japan has approved nivolumab as well. Here we focused on cancer immunity techniques to identify additional targets and biomarkers for the treatment of EHCC.

Recently, overexpression of programmed death ligand 1, which is an immunomodulated ligand expressed in tumor cells, was shown to be correlated with poor prognosis for several types of tumors.12 In this study, we focused on immunomodulated ligands expressed in tumors, especially the NKG2D ligands in EHCC. The ligands for the human NKG2D receptor are MICA and MICB and ULBP1–6.13, 14, 15 NKG2D ligands are frequently expressed in many cancer cells and virally infected cells, but are rarely expressed in normal cells.16 The expression of NKG2D ligands is elevated in several malignant tumors including breast, colorectal, hepatocellular, ovarian, and pancreatic carcinomas.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 However, the association between NKG2D ligand expression in cancer cells and cancer prognosis is controversial.23

The NKG2D receptor is an activating receptor that is expressed on all NK cells, most NK T cells, a subset of γδ T cells, and all human CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.14, 15 Although overexpression of NKG2D ligands has been reported in several cancers, the corresponding expression of NKG2D receptors has not been investigated in cancer specimens.

In the present study, we investigated the expression of multiple NKG2D ligands in EHCC tissues to evaluate their prognostic significance and association with clinicopathological factors. Moreover, we investigated the expression of the NKG2D receptor and examined the relationship between this receptor and its ligands.

Materials and Methods

Patients and samples

Eighty‐two patients with EHCC, who underwent surgical treatment at the Department of General Surgical Science, Gunma University Hospital (Maebashi, Japan) or Saiseikai Maebashi Hospital (Maebashi, Japan) between 1995 and 2011, were included in this study. No patients received chemotherapy or irradiation prior to surgery. In 82 patients, the following surgical procedures were carried out: eight patients received extended right or left hepatectomy plus bile duct resection, six patients received left hepatectomy plus bile duct resection, three patients received hepatopancreatoduodenectomy, 59 patients received pancreatoduodenectomy, and six patients received bile duct resection. In total, complete tumor removal (R0, resection) was achieved in 67 patients. In 15 cases, there was microscopic tumor at the cutting margin (R1, resection). Forty‐seven (57.3%) patients received adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection: 10 patients received gemcitabine (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA), 22 patients received S‐1 (TS‐1; Taiho Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), three patients received gemcitabine plus S‐1, and 12 patients received tegafur–uracil (Taiho Pharmaceutical). All clinical samples were used in accordance with institutional guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki after obtaining written informed consent from all participants. Tumor stages were classified according to the seventh TNM classification of the Union for International Cancer Control and the sixth Classification of Biliary Tract Carcinoma of the Japanese Society of Hepato‐Biliary‐Pancreatic Surgery. Clinicopathological findings discussed in this study were based on clinical records and pathology reports.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining was carried out by standard streptavidin–biotin–peroxidase complex methods. Three‐micron‐thick sections were cut from paraffin blocks of EHCC samples and mounted on glass slides. All sections were deparaffinized and incubated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in 100% methanol for 30 min at RT to block endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were then heated in boiling water and Immunosaver (Nisshin EM, Tokyo, Japan) at 98°C for 45 min. Non‐specific binding sites were blocked by incubation with Protein Block Serum‐Free (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) for 40 min. Next, the sections were incubated with primary mouse anti‐MICA/B mAbs (sc‐137242; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), a rabbit anti‐ULBP1 polyclonal Ab (A42608; Atlas Antibodies, Stockholm, Sweden), or goat anti‐ULBP2/5/6 polyclonal Abs (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at 1:800 dilutions, a goat anti‐NKG2D polyclonal Ab (sc‐9621; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:100 dilution, or a rabbit anti‐IFN‐γ Ab (ab9657; Abcam, Tokyo, Japan) at a 1:300 dilution in Can Get Signal Immunostain (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed in PBS and incubated with biotinylated rabbit anti‐mouse secondary Abs (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) against MICA/B, biotinylated goat anti‐rabbit secondary Abs (Nichirei) against ULBP1 and IFN‐γ, or biotinylated rabbit anti‐goat secondary Abs (Nichirei) against ULBP2/5/6 and NKG2D for 30 min at RT. Sections were then incubated with a streptavidin–peroxidase solution for 30 min at RT.

The chromogen 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride was applied as a 0.02% solution containing 0.005% H2O2 in 50 nM ammonium acetate–citrate acid buffer (pH 6.0). The sections were lightly counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin and mounted. Negative controls were carried out by omitting the primary antibody and observing a lack of detectable staining.

Evaluation of immunostaining

Immunohistochemical slides were scanned and subjected to unbiased, blind evaluation by two observers. As tumor staining was relatively homogenous, NKG2D ligand expression was evaluated according to staining intensity and scored as follows: 0, negative, no staining in cancer cells; 1, weak expression, staining of cancer cells was the same as or weaker than that in the cancer stroma; and 2, strong expression, staining of cancer cells was stronger than that in the cancer stroma. Cases with scores of 0 and 1 were classified in the low‐expression group, and cases with a score of 2 were classified in the high‐expression group. In addition, NKG2D receptor expression was evaluated within the cancer stroma. NKG2D‐positive cells were counted in five random fields at 400× magnification and classified further into two groups: high‐expression, staining of cells in more than two fields; and low‐expression, no staining or staining of cells in only one field. Expression of IFN‐γ was evaluated within the cancer stroma and classified as either absent or present.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Student's t‐tests for continuous variables and χ2‐tests for categorical variables. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The differences between survival curves were analyzed with log–rank tests. Prognostic factors were examined by univariate and multivariate analyses using Cox's proportional hazard model. Results were considered statistically significant when the relevant P‐value was less than 0.05, and all statistical analyses were undertaken with JMP 11 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographic characteristics of patients

The clinicopathological characteristics of the 82 patients are shown in Table 1. The median age at the time of surgery was 68 years (range, 36–94 years). There were 58 men (70.7%) and 24 women (29.3%) enrolled. The median duration of follow‐up was 16.5 months.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics and expression of natural killer group 2 member D ligands in patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

| Factors | MICA/B expression | ULBP1 expression | ULBP2/5/6 expression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | P‐value | Low | High | P‐value | Low | High | P‐value | |

| (n = 15) | (n = 67) | (n = 40) | (n = 42) | (n = 32) | (n = 50) | ||||

| Age, years | 0.3154 | 0.6090 | 0.3247 | ||||||

| <65 | 4 | 27 | 14 | 17 | 10 | 21 | |||

| ≥65 | 11 | 40 | 26 | 25 | 22 | 29 | |||

| Gender | 0.3230 | 0.5301 | 0.7529 | ||||||

| Male | 9 | 49 | 27 | 31 | 22 | 36 | |||

| Female | 6 | 18 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 14 | |||

| Histology type | 0.4582 | 0.0149a | 0.0135a | ||||||

| Well/moderately differentiated | 10 | 51 | 25 | 36 | 19 | 42 | |||

| Poorly differentiated | 5 | 16 | 15 | 6 | 13 | 8 | |||

| T factor (UICC) | 0.7751 | 0.3765 | 0.6506 | ||||||

| T1, 2 | 8 | 33 | 18 | 23 | 15 | 26 | |||

| T3, 4 | 7 | 34 | 22 | 19 | 17 | 24 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.9830 | 0.3911 | 0.3282 | ||||||

| Absent | 9 | 40 | 22 | 27 | 17 | 32 | |||

| Present | 6 | 27 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 18 | |||

| Lymphatic invasion (JHBPS) | 0.0407a | 0.0132a | 0.1231 | ||||||

| 0, 1 | 6 | 46 | 20 | 32 | 17 | 35 | |||

| 2, 3 | 9 | 21 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 15 | |||

| Venous invasion (JHBPS) | 0.1786 | 0.0024a | 0.6786 | ||||||

| 0, 1 | 8 | 48 | 21 | 35 | 21 | 35 | |||

| 2, 3 | 7 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 11 | 15 | |||

| Perineural invasion (JHBPS) | 0.2962 | 0.2422 | 0.0003a | ||||||

| 0, 1 | 1 | 11 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 12 | |||

| 2, 3 | 14 | 56 | 36 | 34 | 32 | 38 | |||

| TNM stage (UICC) | 0.1124 | 0.0010a | 0.3111 | ||||||

| I, II | 12 | 63 | 33 | 42 | 28 | 47 | |||

| III, IV | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 3 | |||

| Recurrence | 0.1565 | 0.3539 | 0.0914 | ||||||

| Absent | 4 | 31 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 25 | |||

| Present | 11 | 36 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 25 | |||

JHBPS, Japanese Society of Hepato‐Biliary‐Pancreatic Surgery; MICA/B, MHC class I chain‐related proteins A and B; UICC, International Union Against Cancer staging system; ULBP, unique long 16 binding protein.

P < 0.05.

Expression of NKG2D ligands in clinical EHCC samples

The 82 EHCC specimens were analyzed for NKG2D ligand expression by immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 1). NKG2D ligand expression was observed in tumor cells, but not in normal ductal cells. The NKG2D ligands were expressed extensively in EHCC tissue samples; MICA/B was expressed in 96.3% of all specimens. Among MICA/B‐positive tumors, 3.7% (3/82), 14.6% (12/82), and 81.7% (67/82) were scored as 0, 1, and 2, respectively. Unique long 16 binding protein 1 was expressed in all samples, with scores of 1 and 2 found in 48.8% (40/82) and 51.2% (42/82) of tumors, respectively. Unique long 16 binding protein 2/5/6 was expressed in 76.8% of the specimens, with scores of 0, 1, and 2 in 23.2% (19/82), 15.9% (13/82), and 60.9% (50/82) of tumors, respectively. There was a significant correlation between MICA/B and ULBP1 expression (P = 0.0060), and ULBP1 and ULBP2/5/6 expression (P = 0.0035), but there was no correlation between MICA/B and ULBP2/5/6 expression (P = 0.5052) (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) ligands in human extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma tissues. Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of specimens are shown. Resected extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma specimens were stained using standard streptavidin–biotin–peroxidase complex methods and 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. The expression of NKG2D ligands was evaluated according to the staining intensity observed and scored as follows: 0, negative; 1, weak expression; and 2, strong expression. Cases with scores of 0 and 1 were defined as the low‐expression group, and cases with scores of 2 were defined as the high‐expression group. MHC class I chain‐related proteins A and B (MICA/B) (a), unique long 16 binding protein 1 (ULBP1) (b), and ULBP2/5/6 (c) low/high expression.

Association between the expression of NKG2D ligands and clinicopathological characteristics

The relationships between clinicopathological parameters and the expression of each NKG2D ligand are presented in Table 1. High expression of MICA/B was significantly correlated with low lymphatic invasion (P = 0.0407). In contrast, high ULBP1 expression was significantly correlated with “well/moderately” differentiated (P = 0.0149), low lymphatic invasion (P = 0.0132), low venous invasion (P = 0.0024), and early TNM stage (P = 0.0010). High ULBP2/5/6 expression significantly correlated with well/moderately differentiated histology type (P = 0.0135). All patients with low expression of ULBP2/5/6 showed a high grade of perineural invasion (P = 0.0003). We examined three invasion factors in detail and discovered an association between tumor invasion and NKG2D ligand expression (Fig. S1). No statistically significant associations were observed between NKG2D ligand expression and age, gender, T factor, lymph node metastasis, or recurrence.

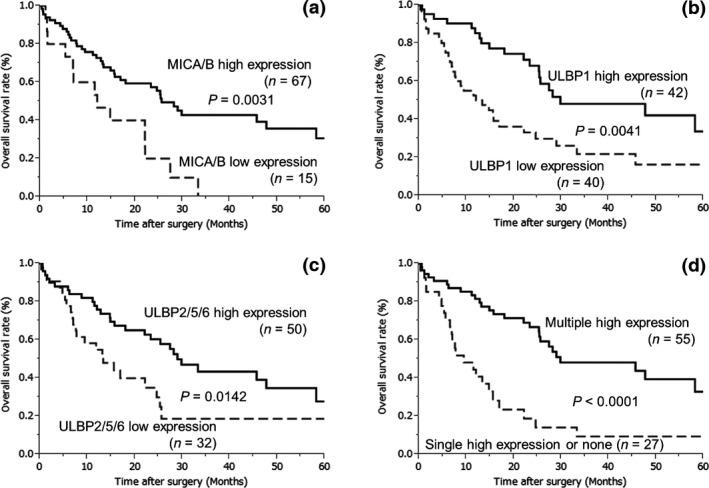

Association between expression of NKG2D ligands and prognosis

The prognostic significance of NKG2D ligand expression is shown in Figure 2. High MICA/B expression was significantly associated with overall and disease‐free survival (P = 0.0031 and P = 0.0012, respectively), as shown in Figures 2(a) and S2(a). Patients with high ULBP1 expression had significantly better overall survival compared to patients with low ULBP1 expression (P = 0.0041; Fig. 2b); however, there was no significant difference in disease‐free survival (P = 0.0582; Fig. S2b). In contrast, ULBP2/5/6 overexpression was significantly associated with overall and disease‐free survival (P = 0.0142 and P = 0.0220, respectively; Figs 2c and S2c).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots showing overall survival in patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma tumors expressing MHC class I chain‐related proteins A and B (MICA/B) (a), unique long 16 binding protein 1 (ULBP1) (b), ULBP2/5/6 (c), and natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) ligand (d). (a) MICA/B overexpression was significantly associated with overall survival (P = 0.0031). (b) High expression of ULBP1 was significantly associated with improved overall survival (P = 0.0041). (c) ULBP2/5/6 overexpression was significantly associated with overall survival (P = 0.0142). (d) High expression of multiple NKG2D ligands was significantly associated with overall survival when compared to high expression of a single ligand or of no ligands (P < 0.0001).

To examine whether studying the expression of multiple NKG2D ligands could enable prognosis, new variables were defined: multiple high expression, in which more than two NKG2D ligands were overexpressed; single high expression, where only one NKG2D ligand was overexpressed; or none, in which no NKG2D ligand was overexpressed. Interestingly, high expression of multiple NKG2D ligands was significantly associated with overall and disease‐free survival (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0006, respectively; Figs 2d and S2d).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of clinicopathological factors associated with overall survival in patients with EHCC

Univariate analysis of 82 EHCC patients revealed that lymphatic invasion (P = 0.0010), venous invasion (P = 0.0004), perineural invasion (P = 0.0035), and NKG2D ligand expression (P = 0.0002) were significantly associated with overall survival. Multivariate analysis revealed that high expression of multiple NKG2D ligands was the only independent, good prognostic indicator (Table 2). Analysis of individual NKG2D ligands is presented in Table S1. Univariate analysis showed that MICA/B expression (P = 0.0080), ULBP1 expression (P = 0.0047), and ULBP2/5/6 expression (P = 0.0181) were significantly associated with overall survival. However, expression of these ligands individually did not show statistical significance by multivariate analysis.

Table 2.

Cox univariate/multivariate regression analysis of variables in relation to overall survival in patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

| Clinicopathological variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | P‐value | RR | 95% CI | P‐value | |

| Age, years (<65 vs ≥65) | 0.78 | 0.45–1.38 | 0.3903 | – | – | – |

| Gender (male vs female) | 0.87 | 0.47–1.56 | 0.6562 | – | – | – |

| Histology type (well or moderately vs poorly differentiated) | 1.88 | 0.99–3.42 | 0.0534 | – | – | – |

| T factor (UICC) (1, 2 vs 3, 4) | 1.60 | 0.92–2.82 | 0.0958 | – | – | – |

| Lymph node metastasis (absent vs present) | 1.72 | 0.96–3.06 | 0.0661 | – | – | – |

| Lymphatic invasion (JHBPS) (0, 1 vs 2, 3) | 2.82 | 1.53–5.20 | 0.0010a | 1.70 | 0.83–3.47 | 0.1456 |

| Venous invasion (JHBPS) (0, 1 vs 2, 3) | 3.05 | 1.66–5.59 | 0.0004a | 1.77 | 0.87–3.60 | 0.1172 |

| Perineural invasion (JHBPS) (0, 1 vs 2, 3) | 3.61 | 1.46–12.01 | 0.0035a | 2.30 | 0.88–7.87 | 0.0927 |

| NKG2D ligands high expression (single or none vs multiple) | 0.32 | 0.18–0.57 | 0.0002a | 0.40 | 0.22–0.74 | 0.0035a |

–, CI, confidence interval; JHBPS, Japanese Society of Hepato‐Biliary‐Pancreatic Surgery; RR, relative risk; UICC, International Union Against Cancer staging system.

P < 0.05.

To investigate the role of NKG2D ligand expression in patients with EHCC before the occurrence of lymph node metastasis, we analyzed 49 patients without lymph node metastases (Table S2). Univariate analysis revealed that lymphatic invasion (P = 0.0380), perineural invasion (P = 0.0142), MICA/B expression (P = 0.0060), and ULBP1 expression (P = 0.0110) were significantly associated with overall survival. Of these factors, ULBP1 expression was the only independent prognostic factor identified by multivariate analysis. In addition, high expression of multiple NKG2D ligands was an independent prognostic factor, as determined by multivariate analysis (Table S3).

Association between NKG2D ligand expression and IFN‐γ secretion

To investigate whether the secretion of cytokines, such as IFN‐γ, influences the overexpression of NKG2D ligands, we evaluated IFN‐γ‐secreting cells in the EHCC specimens. Although IFN‐γ‐secreting cells were present in 36 patients, no association was found between IFN‐γ secretion and NKG2D ligand expression (P = 0.5878; data not shown).

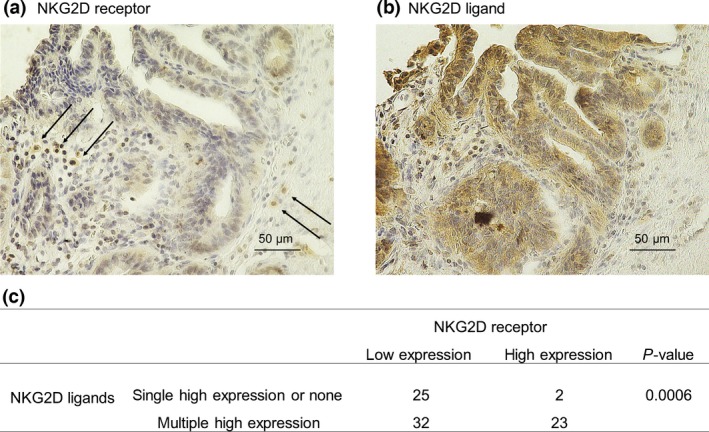

Correlation of expression of NKG2D ligands on tumor cells and expression of NKG2D receptor on stromal cells

To investigate the relationship between NKG2D ligands and the NKG2D receptor, we evaluated the expression of the NKG2D receptor in EHCC specimens by immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 3a). Of the 82 EHCC specimens, 31.3% (25/82) showed high expression of the NKG2D receptor. No significant difference in overall and disease‐free survival was observed between the high and low NKG2D expression groups (P = 0.6091, P = 0.8017, respectively; Fig. S3). Conversely, there was a significant correlation between high expression of multiple NKG2D ligands and high expression of the NKG2D receptor (P = 0.0006; Fig. 3b,c). Among the tumors with high expression of the NKG2D receptor, 92% (23/25) also showed high expression of multiple NKG2D ligands.

Figure 3.

Expression of the natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) receptor in human extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma tissues. Immunohistochemical staining of the NKG2D receptor (a) and the NKG2D ligand, unique long 16 binding protein 1 (b), from the same patient. NKG2D receptor‐stained slides were examined for the presence of NKG2D within the cancer stroma. (c) Correlation between NKG2D ligands and NKG2D receptor expression. Co‐overexpression of multiple NKG2D ligands was significantly correlated with high expression of the NKG2D receptor (P = 0.0006).

Discussion

In this study, we showed that high expression of NKG2D ligands was significantly associated with good prognosis and served as an independent prognostic factor in EHCC. We also showed that high expression levels of ULBP1 and multiple NKG2D ligands were independent prognostic factors in patients with EHCC without lymph node metastases. Thus, co‐expression of multiple NKG2D ligands may be a useful prognostic marker in EHCC, and the expression level of ULBP1 may be a useful prognostic marker for early‐stage EHCC. Moreover, there was a significant correlation between the expression of the NKG2D receptor and the expression of multiple NKG2D ligands, suggesting that the NKG2D receptor–NKG2D ligand interaction may be an important target for controlling cancer progression in EHCC.

The expression of NKG2D ligands is an indicator of cellular stress and can be induced by viral infection or malignant transformation. In normal cells, NKG2D ligands are expressed at low to undetectable levels, avoiding autoimmunity.14, 15, 24 NKG2D ligands can be upregulated in several types of cancer cells. Indeed, high expression of NKG2D ligands is correlated with good a prognosis in colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma,17, 18, 19, 20 but with a poor prognosis in ovarian cancer.21, 25 In our present study, high expression of MICA/B or ULBP2/5/6, individually, showed significant correlation with good overall and disease‐free survival in EHCC. In contrast, high expression of ULBP1 alone significantly correlated with good overall survival.

The majority of previous investigations have been designed to examine the association between single NKG2D ligand expression and prognosis; however, the prognostic values of these results are controversial. To address this shortcoming, we examined the concurrent expression of several NKG2D ligands. Our data showed that the co‐expression of multiple NKG2D ligands was significantly associated with overall survival and acted an independent prognostic factor in EHCC. Thus, we suggest that the co‐expression of multiple NKG2D ligands may be useful as a prognostic marker for EHCC. Furthermore, we investigated the role of NKG2D ligand expression in patients without lymphatic metastasis. The expression of multiple NKG2D ligands and the individual expression of ULBP1 were independent prognostic factors in patients with EHCC. Thus, observation of the co‐expression of multiple NKG2D ligands and the expression of ULBP1 alone may improve prognoses in early‐stage EHCC and may facilitate decision‐making regarding the necessity for adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery.

It has been shown that NKG2D ligands trigger antitumor immunity through the activation of immune cells expressing NKG2D.15, 26 Recent studies have shown that tumors expressing NKG2D ligands are eliminated by NK cells expressing NKG2D in vivo.14, 27, 28 In the present study, we showed a significant correlation between high expression of the NKG2D receptor and the co‐overexpression of multiple NKG2D ligands. Thus, the interaction between multiple NKG2D ligands and the NKG2D receptor may be important for regulating tumor progression.

Several mechanisms, including heat shock, oxidative stress, and DNA damage occurring in response to various agents, have been shown to induce the expression of NKG2D ligands, but their regulatory mechanisms are not fully understood.24, 29, 30, 31 Recent results have shown that programmed death ligand 1 expression can be induced through oncogenic signaling pathways,32 or in response to the production of immune‐stimulating cytokines by tumor‐infiltrating CD8 T cells.33, 34 The latter process has been termed “adaptive immune resistance”35 and represents a mechanism by which tumor cells attempt to protect themselves from immune cell‐mediated killing.36 Currently, little is known of the relationship between cytokines and the expression of NKG2D ligands. In our present study, there was no association between the secretion of IFN‐γ in tumor stroma and the expression of NKG2D ligands in the tumor cells. The role of cytokines in the expression of NKG2D ligands remains elusive and will require careful characterization in future studies.

In conclusion, we showed that high co‐expression of multiple NKG2D ligands correlated with a good prognosis in EHCC. In addition, we confirmed a significant association between the expression of multiple NKG2D ligands and the NKG2D receptor. Our results suggested that the expression of multiple NKG2D ligands might be a useful prognostic marker in EHCC and that therapeutic treatment encouraging the interaction between NKG2D ligands and their receptor may be effective for patients with EHCC.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- EHCC

extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- IFN‐γ

interferon‐γ

- MICA/B

MHC class I chain‐related proteins A and B

- NK

natural killer

- NKG2D

natural killer group 2 member D

- PD‐1

programmed death 1

- RT

room temperature

- ULBP

unique long 16 binding protein

Supporting information

Fig. S1. The expression of NKG2D ligands and invasion factors.

Fig. S2. Kaplan–Meier plots showing disease‐free survival as a function of NKG2D ligand expression.

Fig. S3. Overall and disease‐free survival (Kaplan–Meier) plots as a function of NKG2D receptor expression.

Table S1. Cox univariate/multivariate regression analysis of variables with respect to overall survival.

Table S2. Cox univariate/multivariate regression analysis of variables with respect to overall survival in 49 patients with EHCC, but without lymph node metastases.

Table S3. Cox univariate/multivariate regression analysis of variables in relation to overall survival in 49 patients with EHCC, but without lymph node metastases.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Kenji Kashiwabara for providing valuable cooperation and excellent assistance.

Cancer Sci 107 (2016) 116–122

Funding Information

Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS); grant numbers 26461969, 15K10129 and 15K10085. The work was supported in part by Uehara Zaidan, Medical Research Encouragement Prize of The Japan Medical Association, Promotion Plan for the Platform of Human Resource Development for Cancer and New Paradigms ‐ Establishing Centers for Fostering Medical Researchers of the Future programs by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and Gunma University Initiative for Advanced Research (GIAR).

References

- 1. de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM. Biliary tract cancers. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1368–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA et al Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg 1996; 224: 463–73; discussion 473–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khan SA, Davidson BR, Goldin RD et al Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: an update. Gut 2012; 61: 1657–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nakeeb A, Lipsett PA, Lillemoe KD et al Biliary carcinoembryonic antigen levels are a marker for cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg 1996; 171: 147–52; discussion 152–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khan SA, Emadossadaty S, Ladep NG et al Rising trends in cholangiocarcinoma: is the ICD classification system misleading us? J Hepatol 2012; 56: 848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patel T. Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies. BMC Cancer 2002; 2: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vital Statistics of Japan . Vital, Health and Social Statistics Division, Statistics and Information Department, Minister's Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2013.

- 8. Aljiffry M, Abdulelah A, Walsh M, Peltekian K, Alwayn I, Molinari M. Evidence‐based approach to cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review of the current literature. J Am Coll Surg 2009; 208: 134–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watanabe A, Suzuki H, Yokobori T et al Forkhead box protein C2 contributes to invasion and metastasis of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, resulting in a poor prognosis. Cancer Sci 2013; 104: 1427–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Araki K, Shimura T, Suzuki H et al E/N‐cadherin switch mediates cancer progression via TGF‐β‐induced epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 2011; 105: 1885–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Couzin‐Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science 2013; 342: 1432–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ohaegbulam KC, Assal A, Lazar‐Molnar E, Yao Y, Zang X. Human cancer immunotherapy with antibodies to the PD‐1 and PD‐L1 pathway. Trends Mol Med 2015; 21: 24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cosman D, Mullberg J, Sutherland CL et al ULBPs, novel MHC class I‐related molecules, bind to CMV glycoprotein UL16 and stimulate NK cytotoxicity through the NKG2D receptor. Immunity 2001; 14: 123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Champsaur M, Lanier LL. Effect of NKG2D ligand expression on host immune responses. Immunol Rev 2010; 235: 267–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J et al Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress‐inducible MICA. Science 1999; 285: 727–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, Bauer S, Grabstein KH, Spies T. Broad tumor‐associated expression and recognition by tumor‐derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96: 6879–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Kruijf EM, Sajet A, van Nes JG et al NKG2D ligand tumor expression and association with clinical outcome in early breast cancer patients: an observational study. BMC Cancer 2012; 12: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Watson NF, Spendlove I, Madjd Z et al Expression of the stress‐related MHC class I chain‐related protein MICA is an indicator of good prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 1445–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McGilvray RW, Eagle RA, Watson NF et al NKG2D ligand expression in human colorectal cancer reveals associations with prognosis and evidence for immunoediting. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 6993–7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kamimura H, Yamagiwa S, Tsuchiya A et al Reduced NKG2D ligand expression in hepatocellular carcinoma correlates with early recurrence. J Hepatol 2012; 56: 381–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li K, Mandai M, Hamanishi J et al Clinical significance of the NKG2D ligands, MICA/B and ULBP2 in ovarian cancer: high expression of ULBP2 is an indicator of poor prognosis. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2009; 58: 641–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shi P, Yin T, Zhou F, Cui P, Gou S, Wang C. Valproic acid sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to natural killer cell‐mediated lysis by upregulating MICA and MICB via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benitez AC, Dai Z, Mann HH et al Expression, signaling proficiency, and stimulatory function of the NKG2D lymphocyte receptor in human cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108: 4081–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huergo‐Zapico L, Acebes‐Huerta A, Lopez‐Soto A, Villa‐Alvarez M, Gonzalez‐Rodriguez AP, Gonzalez S. Molecular bases for the regulation of NKG2D ligands in cancer. Front Immunol 2014; 5: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGilvray RW, Eagle RA, Rolland P, Jafferji I, Trowsdale J, Durrant LG. ULBP2 and RAET1E NKG2D ligands are independent predictors of poor prognosis in ovarian cancer patients. Int J Cancer 2010; 127: 1412–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nausch N, Cerwenka A. NKG2D ligands in tumor immunity. Oncogene 2008; 27: 5944–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Diefenbach A, Jensen ER, Jamieson AM, Raulet DH. Rae1 and H60 ligands of the NKG2D receptor stimulate tumour immunity. Nature 2001; 413: 165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cerwenka A, Baron JL, Lanier LL. Ectopic expression of retinoic acid early inducible‐1 gene (RAE‐1) permits natural killer cell‐mediated rejection of a MHC class I‐bearing tumor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98: 11521–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mincheva‐Nilsson L, Baranov V. Cancer exosomes and NKG2D receptor–ligand interactions: impairing NKG2D‐mediated cytotoxicity and anti‐tumor immune surveillance. Semin Cancer Biol 2014; 28C: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raulet DH. Roles of the NKG2D immunoreceptor and its ligands. Nat Rev Immunol 2003; 3: 781–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raulet DH, Gasser S, Gowen BG, Deng W, Jung H. Regulation of ligands for the NKG2D activating receptor. Ann Rev Immunol 2013; 31: 413–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Atefi M, Avramis E, Lassen A et al Effects of MAPK and PI3K pathways on PD‐L1 expression in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 3446–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spranger S, Spaapen RM, Zha Y et al Up‐regulation of PD‐L1, IDO, and T(regs) in the melanoma tumor microenvironment is driven by CD8(+) T cells. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5: 200ra116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bald T, Landsberg J, Lopez‐Ramos D et al Immune cell‐poor melanomas benefit from PD‐1 blockade after targeted type I IFN activation. Cancer Discov 2014; 4: 674–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pardoll DM. The Blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12: 252–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH et al PD‐1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014; 515: 568–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. The expression of NKG2D ligands and invasion factors.

Fig. S2. Kaplan–Meier plots showing disease‐free survival as a function of NKG2D ligand expression.

Fig. S3. Overall and disease‐free survival (Kaplan–Meier) plots as a function of NKG2D receptor expression.

Table S1. Cox univariate/multivariate regression analysis of variables with respect to overall survival.

Table S2. Cox univariate/multivariate regression analysis of variables with respect to overall survival in 49 patients with EHCC, but without lymph node metastases.

Table S3. Cox univariate/multivariate regression analysis of variables in relation to overall survival in 49 patients with EHCC, but without lymph node metastases.