Abstract

The role of cells expressing stem cell markers deltaNp63 and CD44v has not yet been elucidated in peripheral‐type lung squamous cell carcinoma (pLSCC) carcinogenesis. Female A/J mice were painted topically with N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea (NTCU) for induction of pLSCC, and the histopathological and molecular characteristics of NTCU‐induced lung lesions were examined. Histopathologically, we found atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia, squamous dysplasia, and pLSCCs in the treated mice. Furthermore, we identified deltaNp63pos CD44vpos CK5/6pos CC10pos clara cells as key constituents of early precancerous atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia. In addition, deltaNp63pos CD44vpos cells existed throughout the atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias, squamous metaplasias, squamous dysplasias, and pLSCCs. Overall, our findings suggest that NTCU induces pLSCC through an atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia–metaplasia–dysplasia–SCC sequence in mouse lung bronchioles. Notably, Ki67‐positive deltaNp63pos CD44vpos cancer cells, cancer cells overexpressing phosphorylated epidermal growth factor receptor and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, and tumor‐associated macrophages were all present in far greater numbers in the peripheral area of the pLSCCs compared with the central area. These findings suggest that deltaNp63pos CD44vpos clara cells in mouse lung bronchioles might be the origin of the NTCU‐induced pLSCCs. Our findings also suggest that tumor‐associated macrophages may contribute to creating a tumor microenvironment in the peripheral area of pLSCCs that allows deltaNp63pos CD44vpos cancer cell expansion through activation of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling, and that exerts an immunosuppressive effect through activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling.

Keywords: CD44(v9), deltaNp63, mice, N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea, squamous cell carcinoma

Non‐small‐cell lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death.1 In humans, SCC is currently the second most frequent histologic subtype of lung cancer and is the leading subtype of lung cancer in developing countries. It accounted for approximately 40 000 deaths in the USA in 2013. The 5‐year survival rate for SCC is only 16%.2

The most common type of lung cancer is lung adenocarcinoma. The discovery of recurrent genetic alterations in EGFR kinase, as well as fusions involving ALK, has led to a marked change in the treatment of patients with this type of cancer.3, 4, 5, 6 In addition, more recent data have suggested that targeting mutations in BRAF, AKT1, ERBB2, and PIK3CA, and fusions that involve ROS1 and RET, may also be successful.7, 8 Unfortunately, activating mutations in EGFR and ALK fusions are typically not present in lung SCC9 and targeted agents developed for lung adenocarcinoma are largely ineffective against lung SCC.

DeltaNp63 is the predominant p63 isoform expressed in stem cells and in proliferating basal cells of stratified epithelia. DeltaNp63 antibody is markedly superior to the standard p63 antibody in the diagnosis of lung SCC.10 Keyes et al. established that deltaNp63 is an oncogene.11 CD44 is expressed predominantly in hematopoietic cells and normal epithelial cell subsets, whereas variant isoforms (CD44v) with insertions in the membrane‐proximal extracellular region are abundant in epithelial‐type carcinomas. Ishimoto et al. showed that CD44v interacts with xCT and blocks ROS‐induced stress signaling that results in growth arrest, cell differentiation, and senescence.12 Therefore, deltaNp63 and CD44v confer oncogenic activity and resistance to ROS‐induced stress, respectively.11, 12

The tumor microenvironment is increasingly recognized as a key factor in multiple stages of carcinogenesis and metastasis.13 Recently, studies using the gene‐engineered mouse model of lung SCC showed that tumor‐associated inflammatory cells and their expressed chemokines have an important role in cancer initiation and progression.14, 15

A few lung SCC models have been developed for defining SCC cancer biology and detection of novel chemopreventive agents and therapeutics. N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea is a well‐known carcinogen capable of inducing SCCs in the mouse lung through a squamous metaplasia–squamous dysplasia–SCC sequence.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Recently, we have established an NTCU‐induced medium‐term SCC model in mice.24 The purpose of the present study was to determine the histopathological and molecular characteristics of NTCU‐induced mouse lung carcinogenesis, determine the cellular origin of SCCs in this model, and investigate the relationship between the tumor microenvironment and cancer progression in NTCU‐induced SCC.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea (90% purity) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Canada).

Animals and experimental design

The animal experiment protocols were approved by The Laboratory Animal Center of Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine (Osaka, Japan), which is accredited by the Center for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and Use, Japan Health Sciences Foundation.

Female A/J mice were purchased at 5 weeks of age from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed in an animal room with a targeted temperature of 22 ± 3°C, relative humidity of 55 ± 5%, and a 12:12 h light : dark cycle. They were acclimated for 7 days before the start of treatment. Basal diet (MF pellet; Oriental Yeast Co., Tokyo, Japan) and drinking water were available ad libitum during the study. Female mice were used in the present study because female A/J mice have higher sensitivity to lung chemical carcinogenesis than male mice.25 The backs of the mice were shaved 48 h before the initial treatment. Mice at 6 weeks of age were randomized into two groups (each group was randomized into three subgroups) and were treated topically with 75 μL of 0.013 M NTCU dissolved in acetone or acetone alone on the dorsal skin twice a week (with a 3‐day interval) for 16 or 20 weeks. At the end of experimental weeks 16, 20, and 24 (4 weeks after the last treatment), mice were killed under deep anesthesia, and the lungs were excised. After recording all suspected neoplastic lesions for their size and location, lungs were fixed in 10% buffered formalin. After 2 days of fixation, two or three slices were cut from each lobe of the lung and processed for paraffin embedding, sectioned, and stained with H&E for histological examination.

Histopathological analysis

Serial tissue sections were cut from paraffin‐embedded lung specimens, and the first section (2‐μm thick) was stained with H&E for histological examination and the remaining sections (2‐μm thick) were used for immunohistochemical analysis. The lesions, including squamous metaplasia, squamous dysplasia, and SCC were scored from the H&E stained sections of each lung. In bronchiolar squamous metaplasia, the normal columnar epithelium is replaced by flattened squamous epithelium with increased keratin production. In squamous dysplasia, focal to full replacement of the epithelium by atypical cells showing irregular shape and increased nucleus/cytoplasm ratio occurs, but the basement membrane remains intact. The SCCs were characterized by keratin pearls, multiple nuclei, increasing mitotic index, and disrupted architecture of the lung. Localization of SCC was categorized into central and peripheral types according to the criteria of Brooks et al.26 with modification for the mouse. The central type of SCC was defined as tumor localization limited to the bronchus and the peripheral type as tumor localization limited to the bronchiole. The SCCs were also divided into well, moderately, and poorly differentiated subtypes, depending on the degree of squamous differentiation according to the WHO classification.27 Intercellular bridges and keratin pearls are most marked in well‐differentiated SCCs. Those SCCs showing single cell keratinization and nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity were classified as moderately differentiated unless definite keratin pearls and intercellular bridges could be identified. Those SCCs showing marked cellular dyscohesion with extensive infiltration by inflammatory cells were classified as poorly differentiated unless definite keratinization and intercellular bridges could be identified. Alveolar hyperplasia and adenoma were observed in all experimental groups at a low frequency, but not included in the analyses. Histopathological analysis was quantitated and classified blindly by two pathologists.

Immunohistochemical studies

Briefly, lung tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene, hydrated through a graded ethanol series and, for immunohistochemical staining, incubated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were then incubated with 10% normal serum at room temperature for 30 min to block background staining, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with first antibodies. For immunohistochemical staining, sections were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the respective biotinylated secondary antibodies, and immunoreactivity was detected by a 0.02% diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride solution containing 0.05% hydrogen peroxide (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA); nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. For immunofluorochemical staining, immunoreactivity was detected by Alexa Fluor 350‐, 488‐, or 594‐conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). In sections that were not triple‐stained, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). All images were captured using an Olympus BX51 microscope with a DP72 digital camera and cellSens Entry image capture software (version 1.3; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

The antibodies used in the present study were: the clara cell marker CC10 (sc‐9772; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) diluted 1:2000; squamous differentiation markers CK5/6 (MAB1620; Millipore, Billerica, USA) diluted 1:200; dltaNp63 (sc‐8609; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1:1000; CD44v9 (kindly provided by Prof. Saya, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan) diluted 1:10 000; TAM markers CD163L1 (ab126756; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted 1:100, CD68 (ab3163; Abcam) diluted 1:200, and CD204 (bs‐6763R; Bioss, MA, USA) diluted 1:200; EGFR (#1114‐1; Epitomics, Burlingame, CA) diluted 1:15; phospho‐EGFR (pY1068, #1727‐1; Epitomics) diluted 1:100; phospho‐STAT3 (Tyr705, #9145) diluted 1:100; PI3K (#4249) diluted 1:200; phospho‐mTOR (Ser2448, #5536) diluted 1:100; phospho‐PDK1 (Ser241, #3438) diluted 1:100; phospho‐4EBP1 (Thr37/46, #9459) diluted 1:200; phospho‐p70S6K (Thr421/Ser424, #9204; all Cell Signaling Technology, Tokyo, Japan) diluted 1:200; HIF‐1α (NB100‐105; Novus, Cambridge, UK) diluted 1:200; Nrf2 (ab137550; Abcam) diluted 1:200; CDKN2A/p16 INK4A (LS‐B1347/22048; LSBio, Seattle, USA) diluted 1:200; p38α (#8690; Cell Signaling Technology) diluted 1:200; phospho‐p38α (Thy180/Tyr182, #4511; Cell Signaling Technology) diluted 1:200; LSH (#ABD41, Millipore) diluted 1:200; and Trim29 (17542‐1‐AP, ProteinTech, Chicago, USA) diluted 1:200.

Statistical analysis

All mean values are reported as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were carried out using the GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Homogeneity of variance was tested by the F test. Differences in mean values between the control and NTCU groups were evaluated by the two‐tailed Student's t‐test when the variance was homogeneous and the two‐tailed Welch's t‐test when the variance was heterogeneous. Differences in incidences between the control and NTCU treatment groups were evaluated by Fisher's exact test. P‐values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea predominantly induced moderately differentiated peripheral‐type SCCs in bronchioles of mouse lung

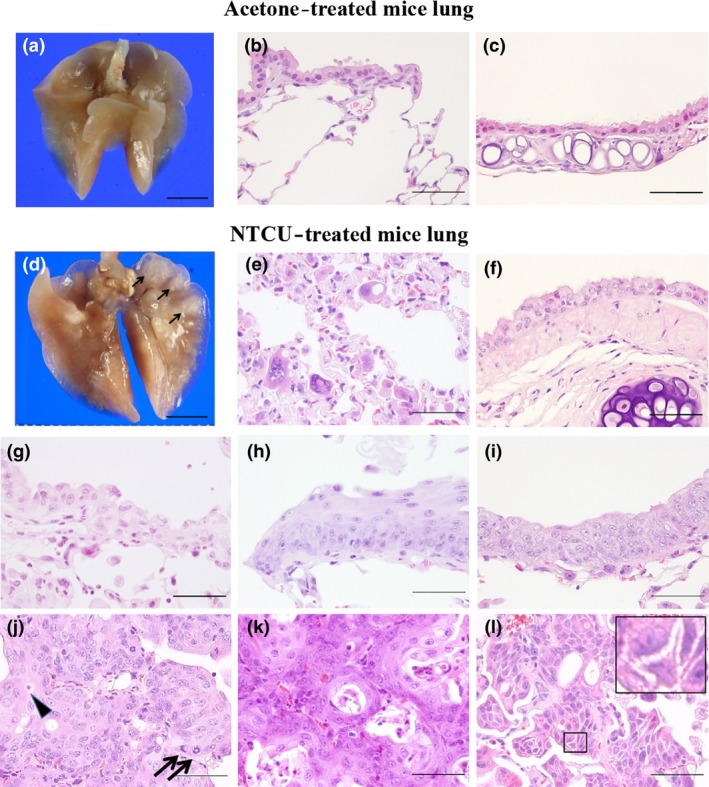

Macroscopically, multiple white‐colored lesions were observed in the periphery of the lungs of NTCU‐treated mice (Fig. 1), but not in the control mice (Fig. 1a). Microscopically, karyomegaly of typeIIpneumocytes in the alveoli (Fig. 1e) and mild degeneration of ciliated cells in the bronchus (Fig. 1f) were observed in all NTCU‐treated mice, but not in the controls (Fig. 1b,c). Atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia characterized by multiple layers of atypical clara‐like cells in bronchioles were observed in all NTCU‐treated mice as early as week 16 (Fig. 1g). These atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias are likely to be presquamous lesions, as discussed below. Squamous metaplasia (Fig. 1h), squamous dysplasia in the bronchioles (Fig. 1i), and SCC (Fig. 1j–l) were also observed in NTCU‐treated mice. As summarized in Table 1, the incidence of squamous metaplasia, squamous dysplasia, and SCC increased in a time‐dependent manner in NTCU‐treated mice; no lesions were observed in the control mice. The incidence and average number of SCC at week 24 were significantly increased compared to the control group. Importantly, the finding that the incidence of squamous metaplasia and squamous dysplasia were increased at the week 24 (4 weeks after cessation of NTCU treatment) compared with week 20 suggests that most, if not all, of the NTCU‐induced squamous epithelial lesions were not reversible. The average numbers of squamous metaplasia, squamous dysplasia, and SCC per mouse were 1.5 ± 1.4, 1.8 ± 3.1, and 0.5 ± 1.2 at week 16; 2.1 ± 2.0, 3.9 ± 3.3, and 2.8 ± 4.5 at week 20; and 2.3 ± 1.5, 7.5 ± 3.9, and 6.8 ± 4.4 at week 24, respectively. The average number of squamous metaplasia and squamous dysplasia at week 20, and squamous metaplasia, squamous dysplasia, and SCC at week 24 were significantly increased compared with their age‐matched control groups. We could not ascertain the exact number of atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias in the present study as these lesions were determined by expression of deltaNp63, CD44v, CK5/6, and CC10 by immunohistochemistry as described below, and some lesions observed in the H&E examinations did not appear in the following immunohistochemical analysis, possibly due to the their small size.

Figure 1.

Representative photographs of acetone‐treated (a–c) and N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea (NTCU)‐treated (d–i) mouse lungs. Macroscopic view (a), normal bronchiole and alveoli (b), and normal bronchus (c) of an acetone‐treated mouse lung. (d) Macroscopic view of NTCU‐treated mouse lung (arrows indicate white lesions in the peripheral portion of the lung). Type II pneumocytes with karyomegaly (e), atypical ciliated cells with cytoplasmic enlargement in NTCU‐treated mouse lung alveoli (f) and atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia in the terminal bronchioles of NTCU‐treated mouse lung (g). (h,i) Squamous metaplasia and squamous dysplasia in the terminal bronchioles of NTCU‐treated mouse lung. (j) Single cell keratinization (arrowhead) and mitotic figures (arrows) are frequently observed in moderately differentiated peripheral‐type lung squamous cell carcinoma. (k, l) Keratin pearls and intracellular bridges are present in well differentiated peripheral‐type lung squamous cell carcinoma. (a, d) Bar = 5 mm. (b, c, e–l) Bar = 100 μm.

Table 1.

Histopathological findings in mouse lung treated with acetone or N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea (NTCU)

| Group | No. of mice | Pre‐neoplastic lesions in bronchiole | SCC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence (%) | Incidence (%) | Total no. of SCC (no./mice) | Localization (%) | Differentiation (%) | |||||||

| Atypical hyperplasia in bronchiole | Squamous metaplasia | Squamous dysplasia | Peripheral type | Central type | Well | Moderate | Poor | ||||

| NTCU 16w | 6 | 6/6 (100)* | 4/6 (67) | 3/6 (50) | 1/6 (17) | 3 (0.5 ± 1.2) | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 (0) | 0/3 (0) | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 (0) |

| NTCU 20w | 9 | 9/9 (100)** | 7/9 (78)* | 7/9 (78)* | 4/9 (44) | 21 (2.8 ± 4.5) | 21/22 (95) | 1/22 (5) | 1/22 (5) | 21/22 (95) | 0/22 (0) |

| NTCU 20w → 4w cessation | 6 | 6/6 (100)** | 6/6 (100)** | 6/6 (100)** | 6/6 (100)** | 41 (6.8 ± 4.4)* | 41/41 (100) | 0/0 (0) | 4/41 (10) | 37/41 (90) | 0/41 (0) |

| Acetone 16w | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Acetone 20w | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Acetone 20w → 4w cessation | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

*P < 0.05 versus age‐matched control; **P < 0.01 versus age‐matched control. SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; w, weeks.

Additionally, SCCs were classified into a peripheral type that arose from the bronchioles and a central type that arose from the bronchus. The incidence of peripheral‐ and central‐type SCCs were 100% and 0% at week 16, 95% and 5% at week 20, and 100% and 0% at week 24, respectively. The incidence of well and moderately differentiated SCCs were 0% and 100% at week 16, 5% and 95% at week 20, and 10% and 90% at week 24. No poorly differentiated SCCs, invasion into intratumoral blood or lymph vessels, or metastasis were noted in any of the groups. These data indicate that NTCU treatment predominantly induced moderately differentiated pLSCCs through an atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia–metaplasia–dysplasia–SCC sequence.

DeltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells in bronchioles might be the origin of squamous lesions in the NTCU‐induced pLSCC mouse model

First, we determined the expression of the clara cell‐specific marker CC10, the squamous cell markers CK5/6 and deltaNp63, and the lung cancer stem/initiating cell marker CD44v in the lungs of control mice and in squamous dysplasias and pLSCCs in NTCU‐treated mice.28, 29, 30 CC10, a secretory protein of clara cells, was expressed in normal bronchiolar cells but was rarely detected in squamous dysplasias or pLSCCs (Fig. S1a). Cells positive for CK5/6 and deltaNp63 were not observed in bronchioles or alveoli in the control mice, but were diffusely present in squamous dysplasias and pLSCCs in NTCU‐treated mice (Fig. S1b,c). A few normal bronchiolar epitheliums were positive for CD44v (Fig. S1d). In contrast, a number of CD44v‐postive cells were observed in the basal cell layers of squamous dysplasias and pLSCCs (Fig. S1d). These data indicate that a histopathologically distinct subpopulation of basal layer cells in squamous dysplasias and pLSCCs expressed squamous differentiation markers CK5/6 and deltaNp63 and stem cell marker CD44v, but not CC10 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of immunohistopathological analysis in mouse lung mouse lung treated with N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea

| Clara cell | Coexpression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CC10 | DeltaNp63pos | DeltaNp63pos | |

| CD44vppos | CD44vpos | ||

| CK5/6pos | CK5/6pos | ||

| CC10pos | CC10neg | ||

| Epithelium of alveoli | − | − | − |

| Bronchiolar epithelium | + | − | − |

| Atypical hyperplasia in bronchiole | + | + | + |

| Squamous metaplasia | − | − | + |

| Squamous dysplasia | − | − | + |

| SCC | − | − | + |

−, Negative; +, positive; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

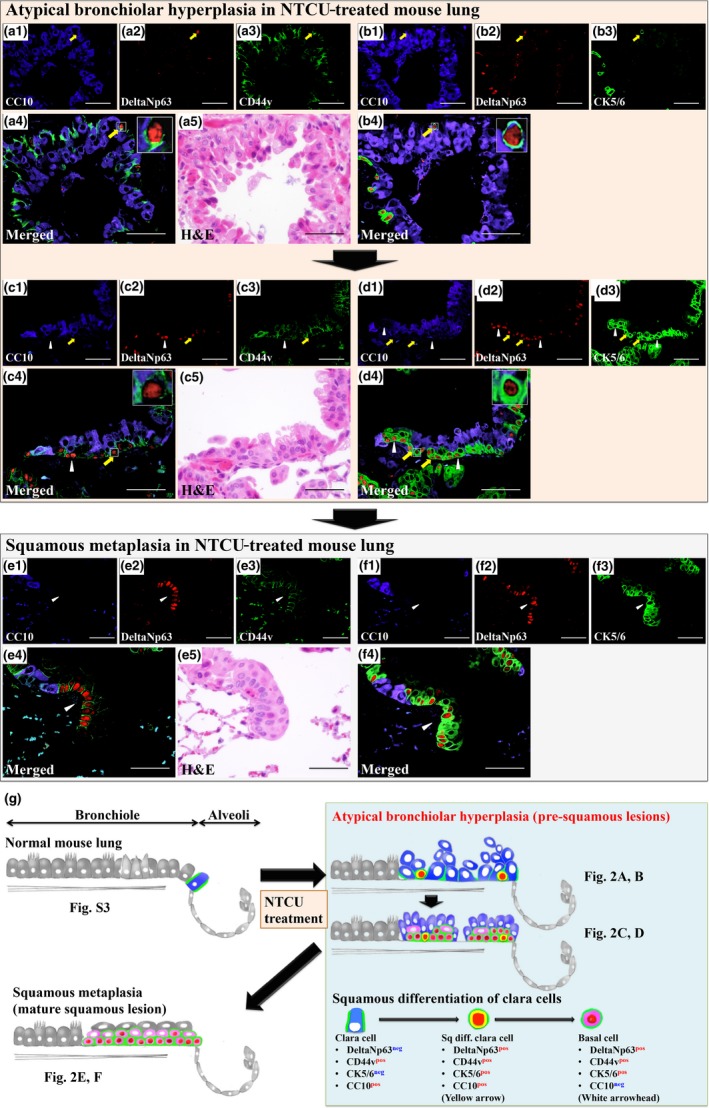

To determine whether clara cells are the origin of squamous lesions in this model, we determined the colocalization of CC10, deltaNp63, CD44v, and CK5/6 in normal lung, atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia, and squamous metaplasia by triple immunohistochemical staining of these markers. Normal lung did not contain deltaNp63posCC10posCD44vpos or deltaNp63posCC10posCK5/6pos cells (Fig. S2). In contrast, atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias did contain deltaNp63posCC10posCD44vpos and deltaNp63posCC10posCK5/6pos cells (Fig. 2a,b). Colocalization of deltaNp63posCC10posCD44vpos and deltaNp63posCC10posCK5/6pos cells in these atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias (Fig. 2a–d, arrows) indicates that these cells were deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells. Some atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias contained only a few deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells, but others contained several deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells and also deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10neg cells (Fig. 2c,d, arrowhead), especially in the basal layer (Fig. 2c,d). It is reasonable to presume that atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias with numerous deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos and deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10neg cells developed from hyperplasias with fewer deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos cells (Fig. 2a–d). The basal layer of mature squamous metaplasias was composed of deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10neg basal cells (Fig. 2e,f, arrowheads), suggesting that these squamous metaplasias were derived from the deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos, deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10neg atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias (Fig. 2c–f). It should be noted that deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells were only observed in atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia but not in mature squamous metaplasia (Fig. 2e–f) or the lungs of control mice (Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Colocalization of CC10, deltaNp63, and CD44v or CK5/6 proteins in atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia and squamous metaplasia of N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea (NTCU)‐treated mouse lung and a schematic summary of the generation of these lesions. (a, b) Triple immunohistological staining using serial sections for CC10, deltaNp63, and CD44v or CK5/6 in atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias (a, b and c, d are serial sections). CC10‐deltaNp63‐CD44v triple‐positive cells (a, yellow arrow) and CC10‐deltaNp63‐CK5/6 triple‐positive cells (b, yellow arrow) were only detected in atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias. DeltaNp63‐CD44v double‐positive, CC10 negative cells (c, white arrowhead) and deltaNp63‐CK5/6 double‐positive, CC10 negative cells (d, white arrowheads) were detected surrounding CC10‐deltaNp63‐CD44v triple‐positive cells (c, yellow arrow) and CC10‐deltaNp63‐CK5/6 triple‐positive cells (d, yellow arrows) in atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias. (e, f) Triple immunohistological staining using serial sections for CC10, deltaNp63, and CD44v or CK5/6 in mature squamous metaplasia (e, f are serial sections). DeltaNp63‐CD44v double‐positive, CC10 negative cells (e, white arrowheads) and deltaNp63‐CK5/6 double‐positive, CC10 negative cells (f, white arrowheads) colocalize, indicating that these cells are deltaNp63, CD44v, and CD5/6 triple‐positive and ‐negative for CC10 (deltaNp63pos CD44vpos CK5/6pos CC10neg cells). The base layer of mature squamous metaplasia is composed of deltaNp63pos CD44vpos CK5/6pos CC10neg cells. (g) Schematic summary of these immunohistochemical analyses and the early process of N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea‐induced squamous differentiation. Sq diff., squamous differentiated. Bar = 100 μm.

Role of deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cells in progression of pLSCCs

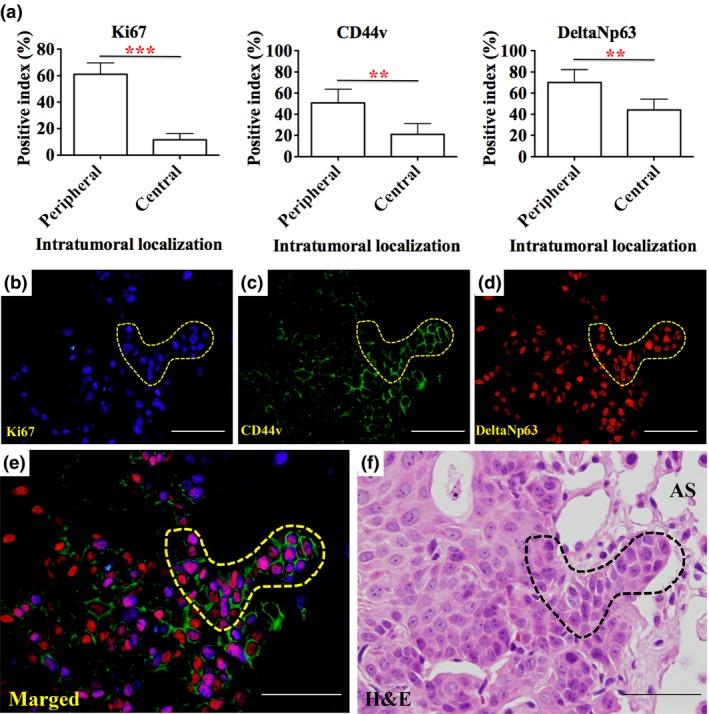

To clarify the role of deltaNp63posCD44vpos cells in the progression of pLSCCs, we examined Ki67, CD44v, and deltaNp63 expression in NTCU‐induced pLSCCs at week 24 (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the positive index of all markers was significantly increased in the peripheral area of the pLSCCs compared with the central area (Fig. 3a). Triple staining of Ki67, CD44v, and deltaNp63 revealed that deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cells in the peripheral area of the pLSCCs had high cell proliferation activity. Furthermore, cancer cells expanding into the alveolar space were generally deltaNp63posCD44vpos cells (Fig. 3b–f, dotted line). In contrast, Ki‐67 expression was seldom detected in CD44vpos or deltaNp63pos cells in precancerous lesions – atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias, squamous metaplasias, or squamous dysplasias – or in CD44vpos or deltaNp63pos cells in the alveoli or bronchi of NTCU‐treated mice (Fig. S3). Importantly, CD44v downstream molecules p38α and phospho‐p38α were observed in CD44vpos cancer cells, and deltaNp63 downstream molecules LSH and Trim29 were observed in deltaNp63pos cancer cells (Fig. S4). These findings indicated that deltaNp63 and CD44v were functionally active in the deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cells.

Figure 3.

Colocalization of Ki67, CD44v, and deltaNp63 in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and CD44vposdeltaNp63pos cancer cell expansion in the invasive front intruding into the surrounding alveoli. (a) Ki67, CD44v and deltaNp63 positive indexes were significantly higher in the peripheral area of SCCs compared with the central area (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (b–f) High magnification of the peripheral area of an SCC. Ki67 is highly expressed in CD44vposdeltaNp63pos cancer cells in the invasive front (dotted line). AS, Alveolar Space,. (b–f) Bar = 100 μm.

The Cancer Genome Atlas study of human lung SCCs shows frequent alterations in the CDKN2A/RB1, NFE2L2/KEAP1/CUL3, PI3K/AKT, and SOX2/TP63/NOTCH1 pathways, suggesting abnormalities in cell cycle control, response to oxidative stress, apoptotic signaling, and squamous cell differentiation. We examined the expression patterns of key factors in the above pathways in pLSCCs at week 24: the PI3K/mTOR signaling molecules PI3K, phospho‐PDK1 (Ser241), phospho‐mTOR (Ser2448), phospho‐4EBP1 (Thr37/46), phospho‐p70S6K (Thr421/Ser424), and HIF‐1α; the NFE2L2/KEAP1/CUL3 signaling molecule Nrf2; and the CDKN2A/RB1 signaling molecule CDKN2A/p16 INK4A. As shown in Figure S5, while all the molecules were overexpressed in lung pLSCCs, the overexpression was not deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cell‐specific or area‐specific. These findings indicate that while dysregulation of PI3K mTOR, NFE2L2/KEAP1/CUL3, and CDKN2A/RB1 signaling pathways might be involved in NTCU‐induced pLSCCs, these pathways do not specifically contribute to deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cell proliferation.

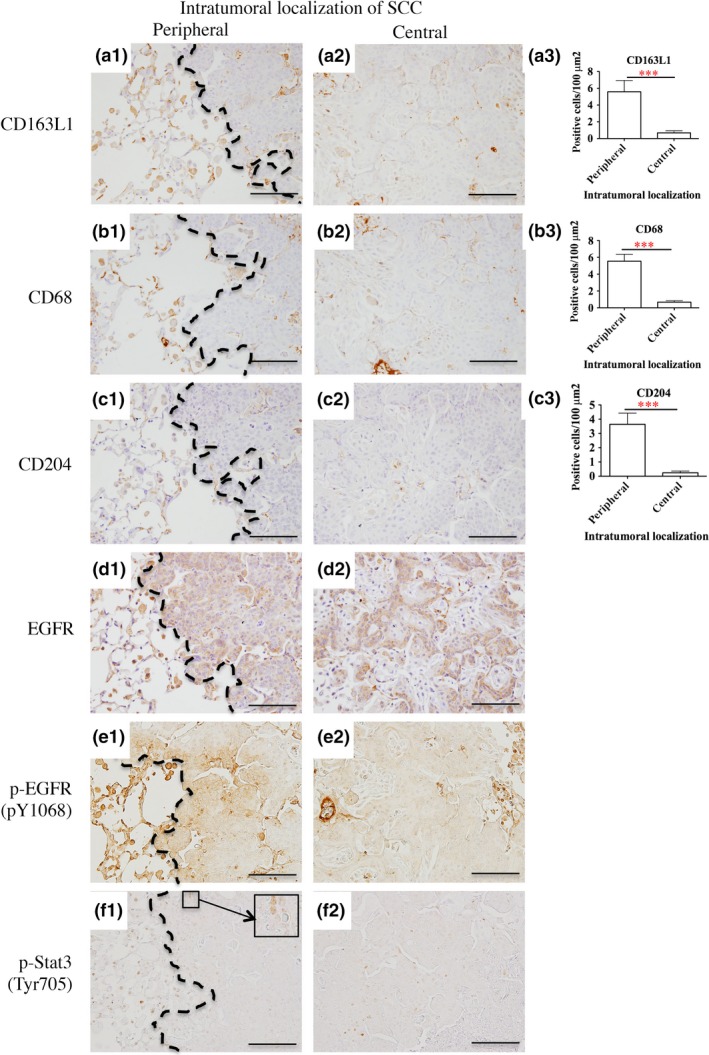

Existence of TAMs in pLSCCs

There is a strong association between poor survival and increased macrophage density in thyroid, lung, and hepatocellular cancers.31 We determined the existence of TAMs in pLSCCs at week 24 using TAM markers CD163L1 (Fig. 4a1–3), CD68 (Fig. 4b1–3), and CD204 (Fig. 4c1–3). Positive TAMs were significantly increased in the peripheral area of pLSCCs compared with the central area. Epidermal growth factor expressed by macrophages and CSF‐1 expressed by tumor cells set up the well‐known EGF/CSF‐1 paracrine loop that promotes tumor initiation, progression, and malignancy by TAMs. The EGFR‐ and CSF‐1‐mediated activation of STAT3 in tumor cells and tumor‐associated immune cells is one of the key mechanisms by which TAMs provide support to tumors.32 Although expression of EGFR in the peripheral area of the pLSCCs was not different compared with the central area, phospho‐EGFR (pY1068) and phospho‐STAT3 (Tyr705) expression in the peripheral area of pLSCCs were higher than in the central area (Fig. 4d–f). In contrast, TAMs and phospho‐EGFR were seldom detected in precancerous lesions (atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias, squamous metaplasias, and squamous dysplasias) and phospho‐STAT3 was not detected in these lesions (Fig. S6). These data suggest that TAMs contribute to the high proliferation activity of deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cells in the peripheral area of pLSCCs through the activation of EGFR/Ras/MAPK and phospho‐STAT3 signaling pathways in cancer cells.

Figure 4.

Tumor‐associated macrophage (TAM) infiltration and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling pathways. (a–c) TAM markers CD163L1 (a), CD68 (b) and CD204 (c) were counted in the peripheral and central areas of peripheral‐type lung squamous cell carcinoma (pLSCCs). The number of positive cells per 100 μm2 was significantly higher in the peripheral area compared with the central area (***P < 0.001). (d–f) Pan‐EGFR (d), phospho‐EGFR (e), and phospho‐STAT3 (f) staining in the peripheral and central areas of pLSCCs. Bar = 100 μm. Although expression of EGFR in the peripheral area of pLSCCs was not different compared with the central area, phospho‐EGFR (pY1068) and phospho‐STAT3 (Tyr705) expression in the peripheral area was higher than in the central area. Dotted lines show the boundary between the tumor and surrounding tissues.

Discussion

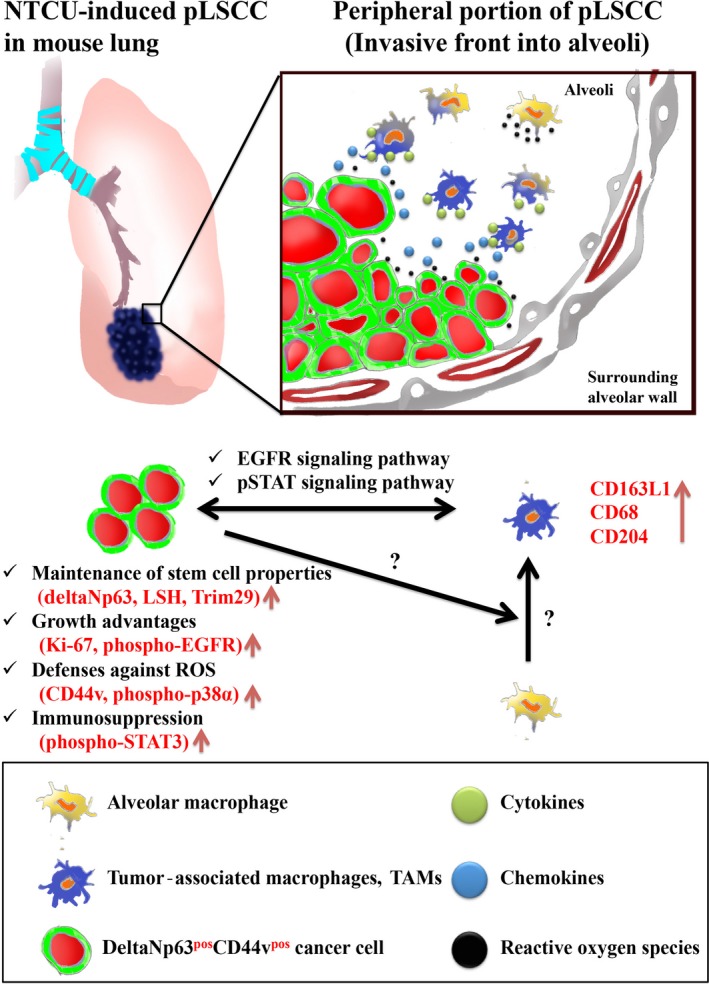

Our previous study showed that NTCU is a strong lung carcinogen capable of inducing SCCs in mice and that this NTCU‐induced mouse SCC model is useful for analysis of the carcinogenic mechanism of lung SCC.24 In this study, we showed that NTCU‐induced lung SCCs in mice were predominantly peripheral and resembled the characteristics of human pLSCC including histopathological location, differentiation grade, and growth pattern. In the present study, we identified deltaNp63posCD44vpos cells as having important roles in the initiation, promotion, and progression stages of the development of pLSCCs in the NTCU‐induced lung carcinogenesis mouse model (summarized in Fig. 2g). In addition, we found that TAMs are important components in the inflammatory microenvironment and are also involved in the progression of pLSCCs (summarized in Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Working model of peripheral‐type lung squamous cell carcinoma (pLSCC) development in the N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea (NTCU)‐mouse model. Tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) that express CD163L1 and/or CD68 and/or CD204 might facilitate deltaNp63pos CD44vpos cancer cell expansion, invasion into surrounding alveoli, and immunosuppression through epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathways in the peripheral portion of pLSCCs. Vertical arrows (red) indicate upregulation. LSH, Lymphoid‐specific helicase, ROS, reactive oxygen species.

In humans, SCC is currently the second most frequent histologic subtype of lung cancer and is the leading subtype of lung cancer in developing countries. Lung SCCs can be classified into central and peripheral types according to the location of the primary site. The central type of lung SCC in humans is generally thought to arise from the bronchial metaplastic epithelium through a metaplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma sequence, which is a well‐known carcinogenic process similar to that observed in uterine cervical neoplasia. Exposure to cigarette smoke can cause central lung SCC, especially in patients who smoked cigarettes with high tar The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) ratings26

Peripheral‐type lung SCCs are mainly classified as moderately differentiated. Based on the histologic growth pattern, pLSCCs are classified under three subgroups: the alveolar space‐filling type, the expanding type, and the combined type. It is reported that the alveolar space‐filling type showed neither lymph node metastasis nor lymphatic vessel invasion and had a good prognosis compared to the other types of pLSCCs.33 Funai et al. reported that pLSCCs are now on the increase and comprise approximately 50% of all lung SCCs in Japan.33 However, the carcinogenic process of the development of pLSCCs has not yet been elucidated.

We characterized atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia, squamous metaplasias, squamous dysplasias, and pLSCCs that developed in NTCU‐treated mice by immunohistochemical analyses of expression of makers for pulmonary epithelial cells, squamous differentiation, and lung stem cells. We found that deltaNp63posCD44vpos cells existed throughout atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias, squamous metaplasias, squamous dysplasias, and pLSCCs. In one type of atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia only deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells were present, whereas in a second type of atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia both deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos and deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10neg cells were present. Notably, the first type of hyperplasia had fewer deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos cells than the second type. These results suggest that the first type of hyperplastic lesion gave rise to the second type of hyperplastic lesion. Importantly, the squamous metaplasias, squamous dysplasias, and pLSCCs contained deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10neg but not deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos cells, suggesting that the second type of hyperplastic lesion gave rise to these squamous lesions. Overall, we propose that clara cells gave rise to NTCU‐induced pLSCCs through an atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia–metaplasia–dysplasia–SCC sequence (summarized in Fig. 2g).

In the distal bronchiolar region of the mouse lung, variant clara cells (CC10posCyp2f2neg cells adjacent to the calcitonin gene‐related peptide‐positive neuroendocrine body) and bronchioalveolar stem cells (CC10posSPCpos cells) have already been reported as stem cell candidates.34, 35, 36 However, cytochrome P450 isozyme 2 F2 but not surfactant protein‐C was expressed in the cytoplasm of deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells in the atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias (data not shown). Moreover, calcitonin gene‐related peptide‐positive neuroendocrine bodies were not detected in the atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias or any squamous lesions (data not shown). These results suggest that neither CC10posCyp2f2neg variant clara cells nor bronchioalveolar stem cells were the cell type that gave rise to pLSCC in NTCU‐exposed mice. Recent studies showed that de‐differentiation of clara cells to basal cells occurred in the basal cell depletion model and the bleomycin‐ and influenza‐based lung injury models in vivo.37, 38 These data support the possibility that deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells are cancer stem cell candidates of pLSCCs in the mouse NTCU model. Further studies are needed to clarify the origin of deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells.

Keyes et al. established that deltaNp63 is an oncogene that bypasses Ras‐induced senescence to drive tumorigenesis and suggested that Lsh‐mediated chromatin‐remodeling events are critical to this process.11 Ishimoto et al. showed that CD44v and its association with xCT block the ROS‐induced stress signaling that results in growth arrest, cell differentiation, and senescence.12 Therefore, the stem cell markers deltaNp63 and CD44v function in differentiation, intracellular ROS control, and senescence suggesting the possibility that these two molecules may play important roles in the development of pLSCCs in NTCU‐exposed mice. Interestingly, we found that deltaNp63posCD44vpos cells were mostly observed in the peripheral area of pLSCCs, where cells showed higher cell proliferation activity compared with cells in the central area of pLSCCs. This finding is reasonable as cancer cells in the peripheral area of a tumor should be resistant to ROS as they frequently encounter a large number of inflammatory cells that produce ROS. Furthermore, we found that deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cells expressed Trim29 and LSH (Fig. S4); these two proteins have been implicated in inhibition of p53 activity and bypass of oncogene‐induced senescence. These findings suggest that there is a specific niche in the peripheral area of pLSCCs where deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cells expand.

Originally, it was proposed that macrophages were involved in antitumor immunity, however, there is substantial clinical and experimental evidence that, in the majority of cases, TAMs also enhance tumor progression to malignancy.39 Hirayama et al. reported that TAMs were an independent prognostic factor in lung SCC.40 It has been suggested that an EGF/CSF‐1 paracrine loop and constitutive activation of STAT3 in TAMs and tumor cells are the key mechanisms by which TAMs provide trophic support to tumors.39, 41, 42, 43 In the present study, colocalization of proliferative cancer cells and TAMs was predominantly observed in the peripheral portion of pLSCCs but not in the central portion. Furthermore, pEGFR was expressed in tumor cell plasma membranes and pSTAT3 was expressed in both tumor cell and TAM nuclei in the peripheral portion of pLSCCs. These findings support the premise that TAMs might play an important role in deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cell expansion, invasion into surrounding alveoli, and the formation of the tumor microenvironment in the peripheral portion of pLSCCs through activation of EGFR signaling and immunosuppression by activation of STAT3. Further studies, however, are needed to ascertain the origin of these TAMs in the NTCU‐induced pLSCC mouse model.

In summary, we showed that NTCU‐induced lung cancers in mice are predominantly pLSCCs that are similar to human pLSCC. We also showed that NTCU induced pLSCCs through an atypical bronchiolar hyperplasia–metaplasia–dysplasia–SCC sequence. We identified deltaNp63posCD44vposCK5/6posCC10pos clara cells in atypical bronchiolar hyperplasias as a probable origin of pLSCCs in this model. Finally, a tumor microenvironment constructed with TAMs and deltaNp63posCD44vpos cancer cells in the peripheral area of pLSCCs is likely to be important for cancer progression in NTCU‐exposed mice.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- ALK

anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- CDKN2A

cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor 2A

- CSF‐1

colony‐stimulating factor‐1

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- 4EBP1

eIF4E‐binding protein 1

- HIF‐1α

hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α

- INK4A

cyclin‐dependent kinase 4 inhibitor A

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- Nrf2

nuclear respiratory factor‐2

- NTCU

N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea

- PDK1

phosphoinositide‐dependent protein kinase‐1

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase

- pLSCC

peripheral‐type lung squamous cell carcinoma

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TAM

tumor‐associated macrophage

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Clara cell, squamous differentiation, and pulmonary stem cell markers in normal bronchioles and alveoli in Acetone‐treated mice and in squamous dysplasia and SCC in NTCU‐treated mice.

Fig. S2. Co‐localization of CC10, deltaNp63, and CD44v or CK5/6 proteins in acetone‐treated mouse lung bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli.

Fig. S3. Co‐localization of ki‐67 and CD44v or deltaNp63 in precancerous lesions, normal alveoli and bronchi, and esophagus in NTCU‐treated mouse lung.

Fig. S4. p38α and phospho‐p38α expression in CD44v positive cancer cells, and LSH and Trim29 expression in deltaNp63 positive cancer cells.

Fig. S5. Expression of human lung squamous cell carcinoma progression markers in deltaNp63 positive cancer cells.

Fig. S6. Examination of TAMs, phospho‐EGFR, and phospho‐STAT3 expression in precancerous lesions in NTCU‐treated mice lung.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Kakenhi Grant No. 25861248), and Smoking Research Foundation. We are grateful to Kaori Nakakubo, Rie Onodera, Azusa Inagaki, Keiko Sakata, Yuko Hisabayashi, and Yukiko Iura for their technical assistance.

Cancer Sci 107 (2016) 123–132

Funding Information

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Smoking Research Foundation

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA 2015; 65: 5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA 2013; 63: 11–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M et al Identification of the transforming EML4‐ALK fusion gene in non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Nature 2007; 448: 561–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC et al EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science 2004; 304: 1497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R et al Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non‐small‐cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2129–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M et al EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 13306–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Felip E, Gridelli C, Baas P, Rosell R, Stahel R. Metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer: consensus on pathology and molecular tests, first‐line, second‐line, and third‐line therapy: 1st ESMO Consensus Conference in Lung Cancer; Lugano 2010. Ann Oncol 2011; 22: 1507–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ju YS, Lee WC, Shin JY et al A transforming KIF5B and RET gene fusion in lung adenocarcinoma revealed from whole‐genome and transcriptome sequencing. Genome Res 2012; 22: 436–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rekhtman N, Paik PK, Arcila ME et al Clarifying the spectrum of driver oncogene mutations in biomarker‐verified squamous carcinoma of lung: lack of EGFR/KRAS and presence of PIK3CA/AKT1 mutations. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 1167–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bishop JA, Teruya‐Feldstein J, Westra WH, Pelosi G, Travis WD, Rekhtman N. p40 (DeltaNp63) is superior to p63 for the diagnosis of pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2012; 25: 405–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keyes WM, Pecoraro M, Aranda V et al DeltaNp63alpha is an oncogene that targets chromatin remodeler Lsh to drive skin stem cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2011; 8: 164–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ishimoto T, Nagano O, Yae T et al CD44 variant regulates redox status in cancer cells by stabilizing the xCT subunit of system xc(‐) and thereby promotes tumor growth. Cancer Cell 2011; 19: 387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen F, Zhuang X, Lin L et al New horizons in tumor microenvironment biology: challenges and opportunities. BMC Med 2015; 13: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xiao Z, Jiang Q, Willette‐Brown J et al The pivotal role of IKKalpha in the development of spontaneous lung squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Cell 2013; 23: 527–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu C, Fillmore CM, Koyama S et al Loss of Lkb1 and Pten leads to lung squamous cell carcinoma with elevated PD‐L1 expression. Cancer Cell 2014; 25: 590–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rehm S, Lijinsky W, Singh G, Katyal SL. Mouse bronchiolar cell carcinogenesis. Histologic characterization and expression of Clara cell antigen in lesions induced by N‐nitrosobis‐(2‐chloroethyl) ureas. Am J Pathol 1991; 139: 413–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Y, Zhang Z, Yan Y et al A chemically induced model for squamous cell carcinoma of the lung in mice: histopathology and strain susceptibility. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 1647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ambrosini V, Nanni C, Pettinato C et al Assessment of a chemically induced model of lung squamous cell carcinoma in mice by 18F‐FDG small‐animal PET. Nucl Med Commun 2007; 28: 647–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khan N, Afaq F, Kweon MH, Kim K, Mukhtar H. Oral consumption of pomegranate fruit extract inhibits growth and progression of primary lung tumors in mice. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 3475–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hudish TM, Opincariu LI, Mozer AB et al N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea induces premalignant squamous dysplasia in mice. Cancer Prev Res 2012; 5: 283–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pan J, Zhang Q, Li K, Liu Q, Wang Y, You M. Chemoprevention of lung squamous cell carcinoma by ginseng. Cancer Prev Res 2013; 6: 530–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang ZX, Cheng ZD, Li CR, Ke AJ, Chen JL, Chen YG. Effects of acupuncture on distribution taxis of paclitaxel in mice with lung cancer. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2014; 34: 1208–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ghosh M, Dwyer‐Nield LD, Kwon JB et al Tracheal dysplasia precedes bronchial dysplasia in mouse model of N‐nitroso trischloroethylurea induced squamous cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0122823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tago Y, Yamano S, Wei M et al Novel medium‐term carcinogenesis model for lung squamous cell carcinoma induced by N‐nitroso‐tris‐chloroethylurea in mice. Cancer Sci 2013; 104: 1560–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singh SV, Benson PJ, Hu X et al Gender‐related differences in susceptibility of A/J mouse to benzo[a]pyrene‐induced pulmonary and forestomach tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett 1998; 128: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brooks DR, Austin JH, Heelan RT et al Influence of type of cigarette on peripheral versus central lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 2005; 14: 576–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart, 4th edn Albany, NY12210, USA: World Health Organization, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Asselin‐Labat ML, Filby CE. Adult lung stem cells and their contribution to lung tumourigenesis. Open Biol 2012; 2: 120094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rawlins EL, Hogan BL. Epithelial stem cells of the lung: privileged few or opportunities for many? Development 2006; 133: 2455–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shimada Y, Ishii G, Nagai K et al Expression of podoplanin, CD44, and p63 in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Cancer Sci 2009; 100: 2054–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang QW, Liu L, Gong CY et al Prognostic significance of tumor‐associated macrophages in solid tumor: a meta‐analysis of the literature. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e50946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kennedy BC, Showers CR, Anderson DE et al Tumor‐associated macrophages in glioma: friend or foe? J Oncol 2013; 2013: 486912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Funai K, Yokose T, Ishii G et al Clinicopathologic characteristics of peripheral squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27: 978–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kotton DN, Morrisey EE. Lung regeneration: mechanisms, applications and emerging stem cell populations. Nat Med 2014; 20: 822–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rawlins EL, Okubo T, Xue Y et al The role of Scgb1a1 + Clara cells in the long‐term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell 2009; 4: 525–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim CF, Jackson EL, Woolfenden AE et al Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell 2005; 121: 823–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tata PR, Mou H, Pardo‐Saganta A et al Dedifferentiation of committed epithelial cells into stem cells in vivo. Nature 2013; 503: 218–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zheng D, Yin L, Chen J. Evidence for Scgb1a1(+) cells in the generation of p63(+) cells in the damaged lung parenchyma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014; 50: 595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell 2010; 141: 39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hirayama S, Ishii G, Nagai K et al Prognostic impact of CD204‐positive macrophages in lung squamous cell carcinoma: possible contribution of Cd204‐positive macrophages to the tumor‐promoting microenvironment. J Thorac Oncol 2012; 7: 1790–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol 2007; 7: 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang D, Muller S, Amin AR et al The Pivotal Role of Integrin beta1 in Metastasis of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 4589–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee H, Pal SK, Reckamp K, Figlin RA, Yu H. STAT3: a target to enhance antitumor immune response. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2011; 344: 41–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Clara cell, squamous differentiation, and pulmonary stem cell markers in normal bronchioles and alveoli in Acetone‐treated mice and in squamous dysplasia and SCC in NTCU‐treated mice.

Fig. S2. Co‐localization of CC10, deltaNp63, and CD44v or CK5/6 proteins in acetone‐treated mouse lung bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli.

Fig. S3. Co‐localization of ki‐67 and CD44v or deltaNp63 in precancerous lesions, normal alveoli and bronchi, and esophagus in NTCU‐treated mouse lung.

Fig. S4. p38α and phospho‐p38α expression in CD44v positive cancer cells, and LSH and Trim29 expression in deltaNp63 positive cancer cells.

Fig. S5. Expression of human lung squamous cell carcinoma progression markers in deltaNp63 positive cancer cells.

Fig. S6. Examination of TAMs, phospho‐EGFR, and phospho‐STAT3 expression in precancerous lesions in NTCU‐treated mice lung.