Abstract

Pituitary-specific transcription factor PROP1, a factor important for pituitary organogenesis, appears on rat embryonic day 11.5 (E11.5) in SOX2-expressing stem/progenitor cells and always coexists with SOX2 throughout life. PROP1-positive cells at one point occupy all cells in Rathke’s pouch, followed by a rapid decrease in their number. Their regulatory factors, except for RBP-J, have not yet been clarified. This study aimed to use the 3 kb upstream region and 1st intron of mouse prop1 to pinpoint a group of factors selected on the basis of expression in the early pituitary gland for expression of Prop1. Reporter assays for SOX2 and RBP-J showed that the stem/progenitor marker SOX2 has cell type-dependent inhibitory and activating functions through the proximal and distal upstream regions of Prop1, respectively, while RBP-J had small regulatory activity in some cell lines. Reporter assays for another 39 factors using the 3 kb upstream regions in CHO cells ultimately revealed that 8 factors, MSX2, PAX6, PIT1, PITX1, PITX2, RPF1, SOX8 and SOX11, but not RBP-J, regulate Prop1 expression. Furthermore, a synergy effect with SOX2 was observed for an additional 10 factors, FOXJ1, HES1, HEY1, HEY2, KLF6, MSX1, RUNX1, TEAD2, YBX2 and ZFP36Ll, which did not show substantial independent action. Thus, we demonstrated 19 candidates, including SOX2, to be regulatory factors of Prop1 expression.

Keywords: Pituitary, PROP1, SOX2, Stem/progenitor cell, Transcription factor

The pituitary gland is a major endocrine organ that plays important roles in the growth, metabolism, reproduction, stress response and homeostasis of all vertebrates. The adenohypophysis (anterior and intermediate lobes of the pituitary gland) develops by invagination of the oral ectoderm and acquires the ability to synthesize and secrete many hormones by differentiation into the respective hormone-producing cells under spatiotemporal regulation of various transcription factors. Among them, Prop1, Prophet of PIT1, is specifically expressed in the adenohypophysis and plays a crucial role in the differentiation of hormone-producing cells [1]. A single nucleotide replacement in Prop1 of the Ames dwarf mouse results in abnormal pituitary expansion caused by a defect in migration of the progenitor cells from Rathke’s pouch into the developing anterior lobe and in failure of the hormone-producing cells to differentiate [1, 2]. Persistent expression of Prop1 interferes with anterior pituitary cell differentiation and increases the susceptibility to pituitary tumors [3]. In addition, PROP1 is likely important for dorsal-ventral patterning but not for cell proliferation and cell survival [4].

Recently, several investigators successively reported the relation between PROP1 and pituitary stem/progenitor cells by analyses of stem cell fractions separated by fluorescence activated cell sorting and pointed out the presence of a pituitary stem/progenitor niche [5,6,7]. On the other hand, we demonstrated that PROP1 starts its expression in SOX2-positive pituitary stem/progenitor cells and that SOX2 is consistently present in PROP1-positive cells [8]. In addition, PROP1-positive cells form a stem/progenitor cell niche in the parenchyma of the rat adult anterior lobe [9], as was elaborated on by further characterizations in subsequent reports [10,11,12,13,14]. PROP1 emerges in SOX2-positive cells early in the rat at embryonic day 11.5 (E11.5) and, after 2 days, occupies all cells in the pituitary primordium of Rathke’s pouch [8]. Thereafter, PROP1 quickly fades away in the process of differentiating into committed cells before SOX2 disappearance and hormone appearance in PIT1-positive cells [8], indicating the presence of potent and prompt regulation mechanisms for Prop1 expression. Much less is known about the regulatory mechanism, despite a study by Ward et al. [15] to determine the tissue-specific mechanism of Prop1 expression using comparative genomics. They intensively analyzed three highly conserved regions and found orientation-specific enhancer activity but not a pituitary-specific element. Knockout of Rbp-J, a primary mediator of Notch signaling, revealed a decrease of Prop1 expression [16], but information regarding transcription factors for Prop1 expression is still limited.

In the present study, we attempted to discover potential regulatory factors and to examine whether SOX2 participates in Prop1 expression by reporter assay. Ultimately, the present study demonstrated that the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of Prop1 show cell type-dependent transcriptional activity and that SOX2 can modulate Prop1 expression. In addition, it was revealed that 18 other transcription factors, many of which are involved in early pituitary organogenesis, participate in modulation through the 5’-upstream region of Prop1.

Materials and Methods

Construction of reporter vectors and expression vectors

To obtain serial truncated fragments of the 5’-upstream region and the 1st intron of the mouse Prop1 gene (Accession number: NM_008936.1), specific primer sets for PCR were designed and synthesized (Table 1). The resulting products were ligated to the upstream site of the secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) gene in the pSEAP2-Basic vector or pSEAP2-Promoter vector (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA), respectively. This resulted in the following reporter vectors: Prop1 (–2993/+21), Prop1 (–1840/+21), Prop1 (–1270/+21), Prop1 (–771/+21), Prop1 (–443/+21), Prop1 (–154/+21), Prop1 (+338/+519), Prop1 (+338/+790), Prop1 (+338/+1112) and Prop1 (+338/+1383).

Table 1. List of primers used for construction of fragments of the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of Prop1.

| 5’-upstream region | ||

| Forward primer | –2993 | 5’-aataacgcgtCTAAGATTCAGAGCCAAGCTAG-3’ |

| –1840 | 5’-aatacgcgtTCTGAGGAACAAGGAGAGTAAAG-3’ | |

| –1270 | 5’-aatacgcgtGGAGATCAGGTTGTCCTATGGT-3’ | |

| –771 | 5’-aatacgcgtAATCAGAGTGTACTCGGAACTC-3’ | |

| –443 | 5’-aatacgcgtATGTCCTCCTCTCCACTCGC-3’ | |

| –154 | 5’-aatacgcgtTAAAGGAGAAAGAAAGGCAGC-3’ | |

| Reverse primer | +21 | 5’-aatactcgagGCTAGATACCTGTTTTCTCACAG-3’ |

| 1st intron | ||

| Forward primer | +338 | 5’-aatacgcgtGTGAGTGAATCCCCAGGATG-3’ |

| Reverse primer | +519 | 5’-aatactcgagTTCTCAACCTGTAAAGCGAA-3’ |

| +790 | 5’-aatactcgagAGACACCTGGGAAGGTGGGT-3’ | |

| +1112 | 5’-aatactcgagGTCTATCAATGACGTCTCTGGC-3’ | |

| +1383 | 5’-aatactcgagCTATGGAGGGAGAAAAACGGA-3’ | |

Uppercase letters indicate sequences of the gene to be amplified. Lowercase letters indicate adaptors containing recognition sequences for restriction enzymes Mlu I (acgcgt) in forward primers and Xho I (ctcgag) in reverse primers.

For construction of expression vectors, a full-length open reading frame encoding a number of transcription factors, listed in Supplementary Table 1 (online only), was obtained by PCR amplification using a rat pituitary cDNA library or cDNA clones from the FANTOM DNABook of mouse transcription factors (DNAFORM, Yokohama, Japan) and cDNA clones obtained by distribution and was cloned in frame into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1Zeo+ (pcDNA3.1, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). In the case of non-mouse clones, the amino acid sequence similarity between species was confirmed to be more than 92%.

Cell culture

CHO, GH3, AtT20, LβT2 and Tpit/F1 cells were used for transient transfection assay. CHO (established from Chinese hamster ovaries) [17], GH3 (a pituitary tumor-derived cell line expressing Gh and Prl) [18] and AtT20 (a pituitary tumor-derived cell line expressing proopiomelanocortin) [19] were obtained from the RIKEN Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan). LβT2 cells, which express gonadotropin genes of αGSU, LHβ and FSHβ [20, 21], were provided to us by Dr. P. L. Mellon (University of California, San Diego, CA, USA). Tpit/F1 cells, which were established from a mouse pituitary tumor and do not express any pituitary hormone [22], were provided to us by Dr. K. Inoue (Saitama University, Japan).

The conditions for cell culture, transfection procedures and reporter assays performed by measurement of the secreted alkaline phosphatase activity of the reporter gene products in the culture media were described in a previous paper [23]. Cell maintenance was performed in monolayer cultures in F-12 medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) and Antibiotic Antimycotic Solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for CHO cells, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Gibco) and antibiotics for LβT2 cells or DMEM/F-12 (1:1) medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) horse serum (SAFC Biosciences, St. Louis, MO, USA), 2.5% (v/v) FBS (SAFC Biosciences) and Antibiotic Antimycotic Solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for AtT20, GH3 and Tpit/F1 cells. All cell lines were cultured in humidified 5% CO2–95% air at 37 C, except for Tpit/F1 cells, which were cultured at 33 C, since this cell line was established from transgenic mouse cells immortalized with a temperature-sensitive mutant T-antigen active at 33 C [24].

Transfection and reporter assay

For transient transfection, cells were plated onto a 96-well plate (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 1–2 × 104 cells/100 μl/well. Transfection was performed 24 h after seeding using a mixture of 2.5–4 μl of DNA (10–30 ng reporter vectors and 10 ng expression vectors by adjusting the total DNA to 50–80 ng with empty pcDNA3.1) and FuGENE 6 (0.3 μl; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) or Lipofectamine 2000 (0.2 μl; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) per well. The cell number per well, transfectant, amount of DNA and medium are listed in Table 2. After incubation for 24–72 h, an aliquot (5 μl) of cultured medium was assayed for SEAP activity using the Phospha-Light Reporter Gene Assay System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with a MiniLumat LB 9506 luminometer (Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany).

Table 2. List of conditions for cell cultures using a 96-well plate/100 μl medium.

| Cell line | Cells/well | Transfectant | Reporter vector (ng/well) |

Expression vector (ng/well) |

Total DNA amount * (ng/well) |

Medium |

| CHO | 1.0 × 104 | FuGENE 6 | 10 | 10 | 50 | F12 |

| AtT20 | 1.0 × 104 | LF2000** | 30 | 10 | 70 | DMEM/F12 |

| LβT2 | 2.0 × 104 | FuGENE 6 | 30 | 10 | 60 | DMEM |

| GH3 | 1.0 × 104 | FuGENE 6 | 10 | 10 | 50 | DMEM/F12 |

| Tpit/F1 | 1.5 × 104 | FuGENE 6 | 30 | 10 | 70 | DMEM/F12 |

* The total DNA amount was adjusted by addition of empty pcDNA3.1 to the reporter and expression vectors. ** Lipofectamine 2000.

All values are expressed as means ± SD from quadruplicate transfections of two to three independent experiments. The statistical significance between the activity of each reporter vector and that of the control was determined by Student’s t-test with the F-test. A value of P < 0.01 was considered significant.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

In situ hybridization was performed according to a previous report [25]. The full-length DNA of rat Rpf1 (Pou6f2) was amplified by PCR with a primer set (5’-ATGATAGCTGGACAAGTCAGTAAGCCC-3’ and 5’-TGCTTCCTTCTGATCTATGAACGGTGTG-3’), and cRNA probes for it were prepared by labeling it with digoxigenin (DIG) using a Roche DIG RNA Labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany). Cryosections (7 μm thickness) from the sagittal plane were hybridized with DIG-labeled cRNA probes at 55 C for 16 h and visualized with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody (Roche Diagnostics) using 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP; Roche Diagnostics). Immunohistochemistry was performed according to our previous report [8] with a primary antibody for guinea pig antiserum against rat PROP1 (1:1,000 dilution) produced in our laboratory.

Results

Basal transcriptional activity of the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of Prop1

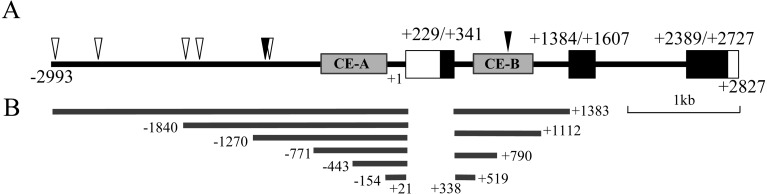

Mouse Prop1 is composed of three exons and two introns and has three regions with high conservation between several mammals [15]: CE-A in the 5’-upstream –733/–155 base (b), CE-B in the 1st intron +593/+1073 b and CE-C in the 3’-downstream +2927/+5123 b. In Fig. 1A, except for the 3’-downstream region, the diagram indicates the structure of mouse Prop1 with putative binding sites for SOX2 (open arrowheads, WCAAWG; W = A or T) [26, 27] and RBP-J (closed arrowheads, GTGGGAA/CACCCTT) [28], which regulates Prop1 expression [16].

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the structure of mouse Prop1. A. Coding and untranslated regions are indicated with closed and open boxes, respectively. Solid lines indicate the 5’-upstream region and introns. Nucleotide numbers from the transcription start site (+1) are indicated below the diagram, and those of coding regions are indicated above the closed boxes. Putative binding sequence of SOX2 (WCAAWG; W = A or T) and RBP-J (GTGGGAA/CACCCTT) are indicated by open and closed inverted triangles, respectively. Shaded boxes (CE-A and CE-B) represent regions evolutionally conserved among the human, chimpanzee, pig, dog, cattle, mouse and rat [15]. B. Truncated constructs of the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron are shown with the nucleotide number. A scale bar (1 kb) is shown below the diagram.

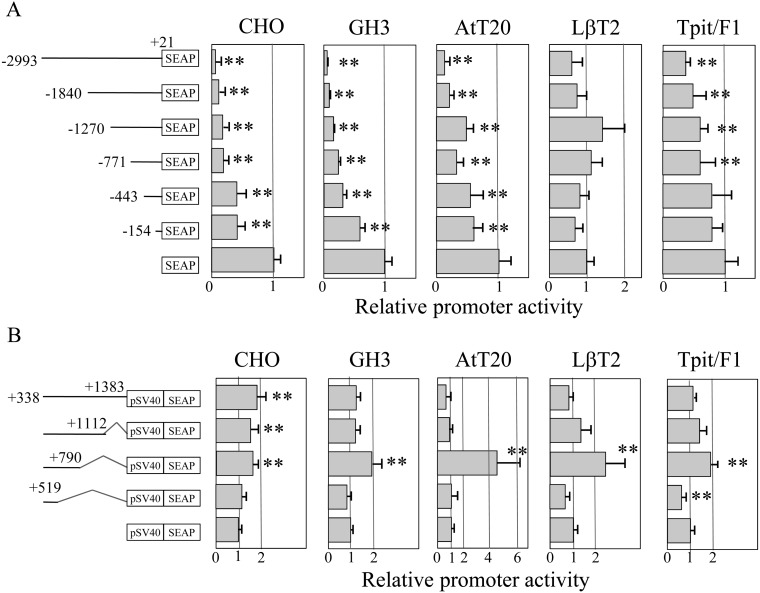

To examine transcriptional activity of the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of Prop1, we constructed deletion mutants of both regions as indicted in Fig. 1B, followed by transfection in CHO, GH3, AtT20, LβT2 and Tpit/F1 cells. Basal transcriptional activity of the truncated upstream region showed low SEAP activity in comparison with that of pSEAP2-Basic vector in CHO, GH3, AtT20 and Tpit/F1 cells, except for LβT2 cells (Fig. 2A). Decreased activity along with an increased length of the upstream region indicated that the upstream –2993/+21 b of Prop1 itself has the ability to suppress its leaky expression, while LβT2 cells did not show a remarkable change. On the other hand, deletion of +791/+1112 b in the 1st intron increased the transcriptional activity in GH3, AtT20 and LβT2 cells (Fig. 2B). Notably, the increase was reduced by deletion of +520/+790 b, indicating the presence of a positive regulatory element in the +520/+790 b and a negative one in some cell types in the +791/+1112 b.

Fig. 2.

Basal transcriptional activity of the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of the mouse Prop1. Diagrams of truncated regions of the 5’-upstream region fused with the pSEAP2-Basic vector (A) and the 1st intron fused with the pSEAP2-Promoter vector containing an SV40 promoter (pSV40) (B) are indicated in the left panels. Kinked lines in the 1st intron (B) indicate deleted regions. Transfection assays were performed, as described in Materials and methods, in CHO, GH3, AtT20, LβT2 and Tpit/F1 cells with quadruplicated transfections in two to three independent experiments, and a representative result (means ± SD) is shown as the relative activity against that of an empty vector. The statistical significance between the activity of each reporter vector was determined by Student’s t-test. ** P < 0.01.

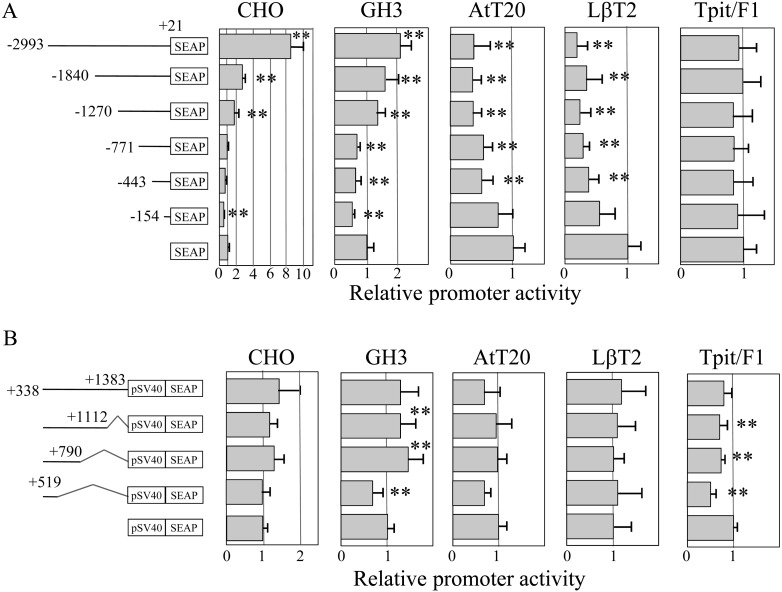

Regulation of transcriptional activity of the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of Prop1 by SOX2

Based on the basal transcriptional activity, we examined whether SOX2 modulates Prop1 expression by co-transfection of a Sox2 expression vector. While Tpit/F1 cells did not have an apparent effect on SEAP activity, SOX2 modulated the transcriptional activities in four cell types (Fig. 3A). SOX2 decreased the activity in AtT20 and LβT2 cells continuously along with increasing the length of the upstream region by 0.5-fold and 0.2-fold, respectively. It acted repressively within –154/+21 in both CHO and GH3 cells but also stimulated the expression of Prop1 (–2993/+21), Prop1 (–1840/+21) and Prop1 (–1270/+21) in both CHO and GH3 cells. Of note, the –2993/–1841 b region showed a remarkable increase of expression in CHO cells.

Fig. 3.

Effect of SOX2 on the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of mouse Prop1. The diagrams shown in the left panel are the same as described in Fig. 2. Transfection assays with expression vector of SOX2 were performed with the same conditions as described in Fig. 2, with quadruplicated transfections in two to three independent experiments. A representative result (means ± SD) is shown, and statistical significance was determined as described in Fig. 2. ** P < 0.01.

A reporter assay for the 1st intron of Prop1 with a SOX2 expression vector was also examined. As shown in Fig. 3B, although there were some effects of SOX2 on the transcriptional activity of each construct in CHO, GH3, AtT20 and Tpit/F1cells, no remarkable influence of SOX2 was present.

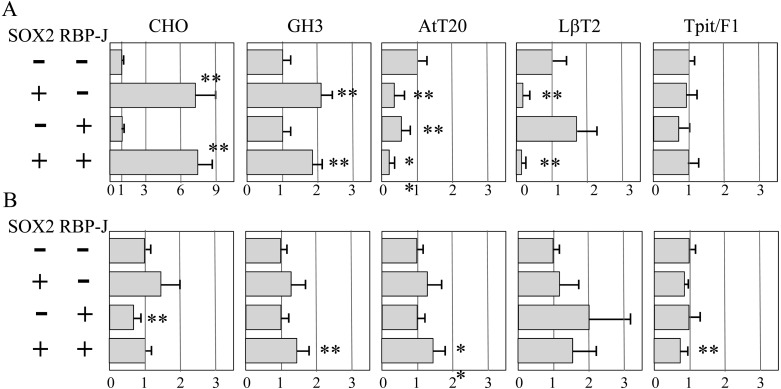

Regulation of transcriptional activity of the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of Prop1 by SOX2 and RBP-J

RBP-J is the only factor known to regulate Prop1 expression [16]. Hence, we sought to find the effect RBP-J has on the transcriptional activity of the 5’-upstream region constructed in the pSEAP2-Basic vector and the 1st intron of Prop1 constructed in the pSEAP2-Promoter vector in the absence or presence of SOX2. RBP-J alone had 0.6- and 0.7-fold repressive effects about in AtT20 and Tpit/F1 cells, respectively, and stimulated the 5’-upstream region by about 1.7-fold in LβT2 cells (Fig. 4A). For the 1st intron, RBP-J had a repressive effect only in CHO cells (about 0.6-fold; Fig. 4B). As a whole, the involvement of RBP-J is likely to be small. Double transfection of SOX2 and RBP-J expression vectors revealed that RBP-J does not have a notable effect on the modulation of SOX2 in both the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of Prop1 in CHO cells.

Fig. 4.

Effect of SOX2 and RBP-J on the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron of mouse Prop1. Transfection assays for 5’-upstream region –2993/+21 (A) and 1st intron (B) in CHO cells were performed with quadruplicated transfections in two to three independent experiments in the absence (–) and/or presence (+) of SOX2- and RBP-J-expression vectors, as indicated in the left panel. A representative result (means ± SD) is shown, and statistical significance was determined as described in Fig. 2. ** P < 0.01.

Regulation of transcriptional activity of the 5’-upstream region of Prop1 by SOX2 and other pituitary transcription factors

The results described above indicate that the 5’-upstream region of Prop1 contains a responsive region(s) for SOX2. As pituitary organogenesis progressed by temporospatial expression of various transcription factors, we focused on 39 additional factors, most of which were assumed to be expressed in the early developmental period based on investigating of microarray data for rat embryonic pituitary cDNA libraries at E14.5 and E15.5 (data not shown). We then examined the factors for their effects on the transcriptional activity of Prop1.

Reporter assays using CHO cells were performed for Prop1 (–2993/+21) by co-transfection of expression vectors without or with a SOX2 expression vector, and their results are summarized in Table 3. Since the assays were performed in different experiments because of a large number of samples, the value of a single effect of SOX2 differed in each experiment (6.6- to 9.9-fold; Table 3, column A). Single transfection of expression vectors showed that 31 factors had little effect (only 0.7- to 1.4-fold), but 8 factors (MSX2, PAX6, PIT1, PITX1, PITX2, RPF1, SOX8 and SOX11) singly modulated the Prop1 expression (Table 3, column B). Notably, only SOX8 repressed Prop1 expression. Next, co-transfection together with a SOX2 expression vector was performed (Table 3, column C), and expression values were normalized by that of SOX2 alone (Table 3, column D). Although 21 out of 31 factors that were ineffective alone did not affect SOX2 activity on the Prop1 expression, the other 10 factors modulated SOX2 activity. Four factors, FOXJ1, HES1, HEY1 and HEY2, stimulated SOX2 activity and 6 factors, KLF6, MSX1, RUNX1, TEAD2, YBX2 and ZFP36L1, repressed them. In each group, HES1, HEY1 and HEY2 increased the SOX2 effect remarkably by 2.2- to 3.8-fold, and RUNX1, TEAD2, YBX2 and ZFP36L1 repressed it by 0.2- to 0.4-fold. On the other hand, 8 factors that each had an effect on Prop1 expression showed almost no effect (MSX2, PAX6, SOX8 and SOX11; 0.8- to 1.1-fold) and/or a weak effect (PIT1, PITX1, PITX2 and RPF1; 1.4- to 1.7-fold) on SOX2 activity. Accordingly, in CHO cells, the reporter assay showed that 19 factors, including SOX2, are potentially able to modulate Prop1 expression.

Table 3. Reporter assay of transcription factors for Prop1 (–2993/+21).

| A | B | C | D | Function | Ref. | ||

| SOX2 only | Factor only | SOX2+Factor | C/A | ||||

| SOX2-dependent stimulation | |||||||

| FOXJ1 | 9.9 ± 1.6** | 0.7 ± 0.0** | 15.6 ± 1.3** | 1.6 | Ependymal cell/astrocyte differentiation | [40] | |

| HES1 | 9.0 ± 1.2** | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 21.3 ± 1.9** | 2.4 | Maintain stemness of the stem cell | [41, 42] | |

| HEY1 | 7.3 ± 1.0** | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 28.0 ± 2.9** | 3.8 | Maintain stemness of the stem cell | [41, 42] | |

| HEY2 | 7.3 ± 1.0** | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 15.7 ± 1.1** | 2.2 | Maintain stemness of the stem cell | [41, 42] | |

| SOX2-dependent suppression | |||||||

| KLF6 | 9.9 ± 1.6** | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 7.3 ± 1.3 | 0.7 | Regulator of Prrx2 in the pituitary | [43] | |

| MSX1 | 8.2 ± 0.9** | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.6** | 0.5 | Pituitary organogenesis | [44] | |

| RUNX1 | 7.3 ± 1.0** | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.4** | 0.4 | Hematopoietic/hair follicle stem cells | [45, 46] | |

| TEAD2 | 9.9 ± 1.6** | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.2** | 0.3 | Vessel/neural tube/heart organogenesis | [47] | |

| YBX2 | 7.6 ± 0.5** | 1.4 ± 0.2** | 2.8 ± 0.5** | 0.4 | Stability of germ cell mRNAs | [48] | |

| ZFP36L1 | 7.3 ± 1.0** | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1** | 0.2 | Vessel/neural tube/heart organogenesis | [49] | |

| SOX2-independent regulation | |||||||

| MSX2 | 6.6 ± 1.1** | 7.7 ± 1.0** | 7.5 ± 2.0 | 1.1 | Cell survival/apoptosis | [50, 51] | |

| PAX6 | 7.3 ± 1.0** | 5.8 ± 0.1** | 7.9 ± 1.2 | 1.1 | Early embryonic pituitary factor | [52] | |

| PIT1 | 9.5 ± 1.9** | 4.8 ± 0.5** | 13.8 ± 1.7 | 1.5 | Generate GH-, PRL- and TSH- cells | [53] | |

| PITX1 | 8.3 ± 0.8** | 9.6 ± 2.7** | 13.0 ± 0.6** | 1.6 | Pan-pituitary activator | [54] | |

| PITX2 | 8.3 ± 0.8** | 16.6 ± 4.3** | 14.4 ± 1.5** | 1.7 | Pituitary formation/cell specification | [55] | |

| RPF1 | 9.9 ± 0.6** | 3.6 ± 0.3** | 13.5 ± 1.8** | 1.4 | Retina/pituitary transcription factor | [13, 56] | |

| SOX8 | 7.6 ± 0.5** | 0.4 ± 0.1** | 6.3 ± 1.1 | 0.8 | Organogenesis | [57] | |

| SOX11 | 9.3 ± 0.4** | 9.2 ± 0.9** | 7.2 ± 1.2 | 0.8 | Neurogenesis and targets TEAD2 | [58, 59] | |

All values are expressed as means ± SD of quadruplicate transfections from two to three independent experiments with reproducible data. Representative data are shown. Statistical analyses for Table 3 were performed as follows. Column A: significance between the values with and without SOX2. Column B: significance between the values with and without factors. Column C: significance between the values with SOX2 + factor and with SOX2 only. ** P < 0.01.

Regulation of transcriptional activity of the 5’-upstream region of Prop1 by singly effective factors

Our results showed the presence of responsive regions for SOX2 in the upstream region of Prop1 (Fig. 3A, Table 4). Similarly, we examined responsive regions for 8 factors, which were each singly effective, by transient transfection of truncated reporter vectors in CHO cells (Table 4). Stimulation was observed in the –2993/–155 b region for MSX2 and PITX2, –2993/–772 b region for PITX1 and PAX6 and –2993/–1271 b region for PIT1 and RPF1, while SOX11 showed stimulation in the –2993/–1841 b and –443/–155 b regions. On the other hand, inhibition was observed in the –154/+21 b region for RPF1 and SOX11, –1270/–772 b region for PIT1 and –1270/–444 b and –2993/–1841 b region for SOX8. Notably, the –2993/–1841 b region showed a remarkable increase in response in comparison with the –1840/–1271 b region. SOX8 did not stimulate any regions, indicating a different role in terms of inhibitory action in comparison with cognate SOX2 and SOX11.

Table 4. Reporter assay of transcription factors for serially truncated reporter vectors of the Prop1 5’-upstream region.

| Reporter vector | Prop1 | Prop1 | Prop1 | Prop1 | Prop1 | Prop1 | Basic |

| (–2993/+21) | (–1840/+21) | (–1270/+21) | (–771/+21) | (–443/+21) | (–154/+21) | vectorb) | |

| SOX2 | 9.4 ± 1.4** | 2.8 ± 0.3** | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1** | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| MSX2 | 7.3 ± 0.7** | 3.2 ± 0.5** | 3.1 ± 0.3** | 2.3 ± 0.3** | 1.8 ± 0.3** | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| PAX6 | 6.1 ± 0.8** | 3.4 ± 0.4** | 2.7 ± 0.2** | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| PIT1 | 3.0 ± 0.3** | 1.6 ± 0.2** | 0.8 ± 0.1** | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.0 |

| PITX1 | 6.9 ± 2.2 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.2** | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| PITX2 | 17.9 ± 3.7** | 6.7 ± 3.0 | 5.6 ± 0.9** | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.4** | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| RPF1 | 2.9 ± 0.3** | 1.5 ± 0.1** | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1** | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| SOX8 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1** | 0.5 ± 0.0** | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| SOX11 | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2** | 0.6 ± 0.1** | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| Controla) | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

All values are expressed in means ± SD of quadruplicate reporter assay using the CHO cell line in two to three independent experiments with reproducible data. Representative data are shown. The statistical significance between the values with and without factors was determined by Student’s t-test. ** P < 0.01. a) The control was assayed with the pcDNA3.1 vector. b) The basic vector was pSEAP2-Basic.

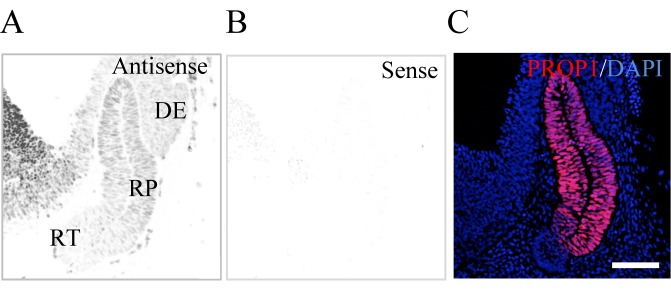

Based on the results of the promoter assay, we were interested in RPF1, which was previously demonstrated to be a novel pituitary transcription factor expressed in Rathke’s pouch with a decrease in expression level toward the birth before, and we previously reported that it is a new pituitary transcription factor in the pituitary gland [13]. Hence, we investigated whether RPF1 and PROP1 coexisted in the early pituitary primordium with in situ hybridization for Rpf1 and immunohistochemistry for PROP1. As expected, Rpf1 transcripts were localized in the rat pituitary primordium (Rathke’s pouch) at E13.5 with a definite low-level signal at the rostral tip (Fig. 5A). Low signals were also localized in the diencephalon (the prospective posterior lobe), and strong signals were present in the cells of the primordium of the hypothalamus (Fig. 5A). PROP1 signals were limited to Rathke’s pouch and overlapped with Rpf1 expression (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

In situ hybridization of Rpf1 and immunohistochemistry for PROP1. In situ hybridization with DIG-labeled anti-sense (A) and sense (B) probes for Rpf1 was performed using the cephalic part at E13.5. A merged image of immunohistochemistry for PROP1 (red) and nuclear staining with 4, 6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, blue; Molecular Probes, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) is shown (C). RP, Rathke’s pouch; DE, diencephalon; RT, rostral tip; HT, hypothalamus. Bar 100 µm.

Discussion

PROP1 is a pituitary-specific transcription factor and plays important roles in pituitary organogenesis and differentiation of hormone-producing cells. However, the regulatory mechanism of Prop1 expression is still poorly understood. In the present study, we examined the transcriptional activity of the 5’-upstream region up to 3 kb and the 1st intron of Prop1 using several cell lines and examined the effects of pituitary transcription factors on Prop1 expression. Finally, this study demonstrated for the first time that SOX2, which is always present in PROP1-positive cells [8], is able to modulate Prop1 expression, and that various transcription factors might participate in the regulation of Prop1 expression in a SOX2-dependent or SOX2-independent manner. These results help us understand the function of regulatory molecules and the mechanism behind the regulation of Prop1 expression during pituitary organogenesis.

We previously demonstrated that expression of Prop1 starts in SOX2-positive cells in the rat pituitary primordium at E11.5 and that PROP1/SOX2 double-positive cells account for all cells in the pituitary primordium of Rathke’s pouch at E13.5 [8]. Thereafter, PROP1-positive cells decrease in number by the postnatal period but retain their Sox2 expression [9]. We also demonstrated that PROP1 promptly faded away in PIT1-positive committed cells [8] before their terminal differentiation into ACTH-positive cells [29], suggesting that Prop1 expression is regulated by SOX2 in rapid stimulation and/or repression by interacting with plural regulatory factors, especially by temporally coexisting with SOX2. Indeed, five putative SOX2-binding sites are present in three 5’-upstream regions of mouse Prop1, –2993/–1841 b, –1840/–1271 b and –1270/–771 b. A promoter assay for SOX2 using CHO cells found responsiveness in these three regions and in an additional region, –154/+21 b. Although the most distal region (–2993/–1841 b) containing two putative binding sites showed remarkable stimulation, the most proximal region (–154/+21 b) showed a repressive effect despite the absence of a putative SOX2 binding site. This regulatory activity of SOX2 on Prop1 expression indicated that some interacting partners of SOX2 exist in CHO cells. Notably, it is known that SOX2 alone does not have transcriptional activity but requires a transcription factor to recognize a particular DNA structure [30] and to create transcriptional activity [31]. Nevertheless, this study demonstrated for the first time that Prop1 expression might function under the modulation of SOX2, providing us with important knowledge for understanding the regulation of Prop1 expression in pituitary stem/progenitor cells and for understanding pituitary organogenesis.

It is interesting to discover regulatory factors for Prop1 expression other than RBP-J, which is the only factor known as a regulator [16]. In the present study, we observed a small effect of RBP-J in four pituitary-derived cell lines and CHO cells. The discrepancy between our data and those of Zhu et al. is probably due to cell type-dependent milieus. In the present study, we performed reporter assays using CHO cells for 39 factors and revealed that 18 factors in addition to SOX2 may participate in the regulation of Prop1 expression in the milieus of CHO cells. These factors are known to be involved in the maintenance of stem/progenitor cells, progress of pituitary organogenesis, cell and tissue specification and differentiation (Table 3). In the present study, they were classified into three groups: Group 1, consisting of FOXJ1, HES1, HEY1 and HEY2, which showed SOX2-dependent stimulation of Prop1 expression; Group 2, consisting of KLF6, MSX1, RUNX1, TEAD2, YBX2 and ZFP36L1, which showed SOX2-dependent suppression; and Group 3, consisting of MSX2, PAX6, PIT1, PITX1, PITX2, RPF1, SOX8 and SOX11, which were singly effective and/or cooperative with SOX2. Since factors classified in Groups 1 and 2 did not have a remarkable effect on Prop1 expression by themselves, they might require interaction with SOX2, which would act as a regulator. SOX2 is known to interact with many transcription factors [32, 33], and its DNA binding ability is remarkably enhanced by interaction with other transcription factors that have a binding site close to the SOX2 binding site [27]. Indeed, we found putative binding sites for some factors examined in this study within 50-base length regions of the SOX2 binding site (Table 5). Additionally, SOX2 is reported to recognize the highly characteristic structure of the four-way DNA junction [30], but the presence of the junction has not been confirmed in mouse Prop1.

Table 5. Putative binding site for transcription factors present within 50-base regions of the five putative SOX2-binding sites in the 5’-upstream region of Prop1.

| SOX2-binding site |

Binding site within 50-base regions of the SOX2-binding sites |

Others1) | ||||

| Region |

Sequence |

SOX2 dependent |

SOX2 independent |

|||

| Stimulation | Repression | Stimulation | Repression | |||

| –2950/–2945 | TCAAAG | HES1, HEY1, HEY2 | ||||

| –2548/–2543 | CTTTGT | PITX1 2), PITX2 2) | MSX1 | PITX1 2), PITX2 2) | MSX2, SOX11 | OTX2 |

| –1874/–1869 | ACAATG | KLF6 | ||||

| –1784/–1779 | CATTGA | HES1, HEY1, HEY2 | ||||

| –1137/–1132 | TCAAAG | RBP-J | ||||

* The putative binding site for transcription factors was analyzed with TRANSFAC (BIOBASE, Waltham, MA, USA). 1) These factors did not show any effect on Prop1 expression in CHO cells. 2) Each of these factors alone stimulated Prop1 expression and further stimulated SOX2 activity.

Zhu et al. reported that HES1 has no effect on Prop1 expression using Hes1-/- mice [16]. However, it has been pointed out that HES1 and HEY1/HEY2 exhibit compensatory action [34] and Raetzman et al. observed high expression levels of Hey1 in the mouse pituitary primordium on E11.5-14.5 [35]. The present study showed that HES1, HEY1 and HEY2 have similar effects on Prop1 expression. Thus, we assume that the HES and HEY families compensate for HES defects in Hes1-/- mice.

Factors in Group 3 showed unique SOX2-independent regulation. Reporter assays for the responsive region of Group 3 revealed that these factors regulate Prop1 expression through the most distal region, –2993/–1841 b, possessing two SOX2-binding sites. Notably, we demonstrated that RPF1, which was recently characterized in the pituitary [13], plays a role in PROP1-positive cells in the early pituitary primordium. On the other hand, PITX2 and SOX11 show unique responses in the –1270/–772 b and –443/–155 b regions, respectively. It is interesting that RPF1 and SOX11, similar to SOX2, repressed transcriptional activity through the proximal –154/+21 b region. The present study suggests that plural spatiotemporally expressing factors comprehensively regulate Prop1 expression to support the progress of early pituitary organogenesis.

Ward et al. conducted a challenge to elucidate the tissue-specific control region in Prop1 using comparative genomics [15]. They focused on the highly conserved regions in the 5’-upstream region and 1st intron (CE-A and CE-B, respectively, shown in Fig. 1) and revealed their enhancer activity and specification of dorsal expression by CE-B, but not their tissue-specific expression [15]. CE-B encompasses a responsive element for RBP-J, a primary mediator of Notch signaling, and is reported to be important for the maintenance of Prop1 expression [16, 36]. We observed that deletion of +791/+112 b remarkably increased Prop1 expression, but further deletion of +520/+790 b eliminated this increased activity (Fig. 2B), indicating the presence of an enhancer element in the +791/+112 b region. However, we observed weak RBP-J-dependent modulation through the 1st intron and the 5’-upstream region, which contain a putative RBP-J binding sequence at –1174/–1168 b (5’-GTGGGAAA-3’).

Thus, the present study suggests for the first time that SOX2, which consistently coexists in PROP1-positive cells, acts as a transcription factor for Prop1 expression with or without interaction with various factors. Additionally, many transcription factors involved in early pituitary organogenesis might participate in the modulation of Prop1 expression. Since Notch signaling is required for Prop1 expression, [16, 36], the present data demonstrating that downstream factors of Notch, HES1, HEY1 and HEY2 [37,38,39], show SOX2-dependent regulation provided us with valuable information concerning the regulation of Prop1 through Notch signaling. At the least, we have confirmed that Rpf1, which was identified as a candidate regulator for Prop1 expression, is expressed in the PROP1-positive cells in the developing pituitary primordium. Further study of the actions of SOX2 and those of other transcription factors on the control of Prop1 might provide us with clues to elucidating transition mechanisms for differentiation during pituitary organogenesis.

Supplementary

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Nos. 21380184 (to YK) and 24580435 (to TK) and by a research grant (A) to YK from the Institute of Science and Technology, Meiji University. It was also supported by the Meiji University International Institute for BioResource Research (MUIIR) and by the Research Funding for Computational Software Support Program of Meiji University. We thanks the following individuals for providing us with cDNA clones: by Dr J Drouin at the Institute de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal (mouse PITX1 cDNA), Dr JC Murray at the University of Iowa (human PITX2 cDNA), Dr J Nathans at Johns Hopkins University (human RPF1 cDNA) and Dr R Tjian at the University of California (human SP1 cDNA).

References

- 1.Sornson MW, Wu W, Dasen JS, Flynn SE, Norman DJ, O’Connell SM, Gukovsky I, Carrière C, Ryan AK, Miller AP, Zuo L, Gleiberman AS, Andersen B, Beamer WG, Rosenfeld MG. Pituitary lineage determination by the Prophet of Pit-1 homeodomain factor defective in Ames dwarfism. Nature 1996; 384: 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward RD, Raetzman LT, Suh H, Stone BM, Nasonkin IO, Camper SA. Role of PROP1 in pituitary gland growth. Mol Endocrinol 2005; 19: 698–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cushman LJ, Watkins-Chow DE, Brinkmeier ML, Raetzman LT, Radak AL, Lloyd RV, Camper SA. Persistent Prop1 expression delays gonadotrope differentiation and enhances pituitary tumor susceptibility. Hum Mol Genet 2001; 10: 1141–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raetzman LT, Ward R, Camper SA. Lhx4 and Prop1 are required for cell survival and expansion of the pituitary primordia. Development 2002; 129: 4229–4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Hersmus N, Van Duppen V, Caesens P, Denef C, Vankelecom H. The adult pituitary contains a cell population displaying stem/progenitor cell and early embryonic characteristics. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 3985–3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gremeaux L, Fu Q, Chen J, Vankelecom H. Activated phenotype of the pituitary stem/progenitor cell compartment during the early-postnatal maturation phase of the gland. Stem Cells Dev 2012; 21: 801–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vankelecom H. Stem cells in the postnatal pituitary? Neuroendocrinology 2007; 85: 110–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshida S, Kato T, Susa T, Cai L-Y, Nakayama M, Kato Y. PROP1 coexists with SOX2 and induces PIT1-commitment cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009; 385: 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida S, Kato T, Yako H, Susa T, Cai L-Y, Osuna M, Inoue K, Kato Y. Significant quantitative and qualitative transition in pituitary stem / progenitor cells occurs during the postnatal development of the rat anterior pituitary. J Neuroendocrinol 2011; 23: 933–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen M, Kato T, Higuchi M, Yoshida S, Yako H, Kanno N, Kato Y. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor-positive cells compose the putative stem/progenitor cell niches in the marginal cell layer and parenchyma of the rat anterior pituitary. Cell Tissue Res 2013; 354: 823–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higuchi M, Yoshida S, Ueharu H, Chen M, Kato T, Kato Y. PRRX1 and PRRX2 distinctively participate in pituitary organogenesis and a cell-supply system. Cell Tissue Res 2014; 357: 323–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yako H, Kato T, Yoshida S, Higuchi M, Chen M, Kanno N, Ueharu H, Kato Y. Three-dimensional studies of Prop1-expressing cells in the rat pituitary just before birth. Cell Tissue Res 2013; 354: 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida S, Ueharu H, Higuchi M, Horiguchi K, Nishimura N, Shibuya S, Mitsuishi H, Kato T, Kato Y. Molecular cloning of rat and porcine retina-derived POU domain factor 1 (POU6F2) from a pituitary cDNA library. J Reprod Dev 2014; 60: 288–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida S, Kato T, Higuchi M, Chen M, Ueharu H, Nishimura N, Kato Y. Localization of juxtacrine factor ephrin-B2 in pituitary stem/progenitor cell niches throughout life. Cell Tissue Res 2015; 359: 755–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward RD, Davis SW, Cho M, Esposito C, Lyons RH, Cheng JF, Rubin EM, Rhodes SJ, Raetzman LT, Smith TP, Camper SA. Comparative genomics reveals functional transcriptional control sequences in the Prop1 gene. Mamm Genome 2007; 18: 521–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu X, Zhang J, Tollkuhn J, Ohsawa R, Bresnick EH, Guillemot F, Kageyama R, Rosenfeld MG. Sustained Notch signaling in progenitors is required for sequential emergence of distinct cell lineages during organogenesis. Genes Dev 2006; 20: 2739–2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puck TT, Cieciura SJ, Robinson A. Genetics of somatic mammalian cells. III. Long-term cultivation of euploid cells from human and animal subjects. J Exp Med 1958; 108: 945–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bancroft FC, Levine L, Tashjian AH., Jr Control of growth hormone production by a clonal strain of rat pituitary cells. Stimulation by hydrocortisone. J Cell Biol 1969; 43: 432–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes SD, Quaade C, Milburn JL, Cassidy L, Newgard CB. Expression of normal and novel glucokinase mRNAs in anterior pituitary and islet cells. J Biol Chem 1991; 266: 4521–4530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas P, Mellon PL, Turgeon J, Waring DW. The L beta T2 clonal gonadotrope: a model for single cell studies of endocrine cell secretion. Endocrinology 1996; 137: 2979–2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pernasetti F, Vasilyev VV, Rosenberg SB, Bailey JS, Huang HJ, Miller WL, Mellon PL. Cell-specific transcriptional regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone-beta by activin and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the LbetaT2 pituitary gonadotrope cell model. Endocrinology 2001; 142: 2284–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, Maruyama D, Sugiyama M, Sakai T, Mogi C, Kato M, Kurotani R, Shirasawa N, Takaki A, Renner U, Kato Y, Inoue K. Cytological characterization of a pituitary folliculo-stellate-like cell line, Tpit/F1, with special reference to adenosine triphosphate-mediated neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide secretion. Endocrinology 2000; 141: 3603–3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Susa T, Kato T, Kato Y. Reproducible transfection in the presence of carrier DNA using FuGENE6 and Lipofectamine2000. Mol Biol Rep 2008; 35: 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mogi C, Miyai S, Nishimura Y, Fukuro H, Yokoyama K, Takaki A, Inoue K. Differentiation of skeletal muscle from pituitary folliculo-stellate cells and endocrine progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res 2004; 292: 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujiwara K, Maekawa F, Kikuchi M, Takigami S, Yada T, Yashiro T. Expression of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH)2 and RALDH3 but not RALDH1 in the developing anterior pituitary glands of rats. Cell Tissue Res 2007; 328: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harley VR, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PN. Definition of a consensus DNA binding site for SRY. Nucleic Acids Res 1994; 22: 1500–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamachi Y, Cheah KS, Kondoh H. Mechanism of regulatory target selection by the SOX high-mobility-group domain proteins as revealed by comparison of SOX1/2/3 and SOX9. Mol Cell Biol 1999; 19: 107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang Y, Chang J, Lynch SJ, Lukac DM, Ganem D. The lytic switch protein of KSHV activates gene expression via functional interaction with RBP-Jkappa (CSL), the target of the Notch signaling pathway. Genes Dev 2002; 16: 1977–1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yako H, Kato T, Yoshida S, Inoue K, Kato Y. Three-dimensional studies of Prop1-expressing cells in the rat pituitary primordium of Rathke’s pouch. Cell Tissue Res 2011; 346: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.P-ohler JRG, Norman DG, Bramham J, Bianchi ME, Lilley DM. HMG box proteins bind to four-way DNA junctions in their open conformation. EMBO J 1998; 17: 817–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamachi Y, Kondoh H. Sox proteins: regulators of cell fate specification and differentiation. Development 2013; 140: 4129–4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang X, Yoon JG, Li L, Tsai YS, Zheng S, Hood L, Goodlett DR, Foltz G, Lin B. Landscape of the SOX2 protein-protein interactome. Proteomics 2011; 11: 921–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reményi A, Lins K, Nissen LJ, Reinbold R, Schöler HR, Wilmanns M. Crystal structure of a POU/HMG/DNA ternary complex suggests differential assembly of Oct4 and Sox2 on two enhancers. Genes Dev 2003; 17: 2048–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imayoshi I, Sakamoto M, Yamaguchi M, Mori K, Kageyama R. Essential roles of Notch signaling in maintenance of neural stem cells in developing and adult brains. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 3489–3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raetzman LT, Wheeler BS, Ross SA, Thomas PQ, Camper SA. Persistent expression of Notch2 delays gonadotrope differentiation. Mol Endocrinol 2006; 20: 2898–2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raetzman LT, Cai JX, Camper SA. Hes1 is required for pituitary growth and melanotrope specification. Dev Biol 2007; 304: 455–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maier MM, Gessler M. Comparative analysis of the human and mouse Hey1 promoter: Hey genes are new Notch target genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 275: 652–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischer A, Schumacher N, Maier M, Sendtner M, Gessler M. The Notch target genes Hey1 and Hey2 are required for embryonic vascular development. Genes Dev 2004; 18: 901–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furukawa T, Mukherjee S, Bao ZZ, Morrow EM, Cepko CL. rax, Hes1, and notch1 promote the formation of Müller glia by postnatal retinal progenitor cells. Neuron 2000; 26: 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacquet BV, Salinas-Mondragon R, Liang H, Therit B, Buie JD, Dykstra M, Campbell K, Ostrowski LE, Brody SL, Ghashghaei HT. FoxJ1-dependent gene expression is required for differentiation of radial glia into ependymal cells and a subset of astrocytes in the postnatal brain. Development 2009; 136: 4021–4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakamoto M, Hirata H, Ohtsuka T, Bessho Y, Kageyama R. The basic helix-loop-helix genes Hesr1/Hey1 and Hesr2/Hey2 regulate maintenance of neural precursor cells in the brain. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 44808–44815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kita A, Imayoshi I, Hojo M, Kitagawa M, Kokubu H, Ohsawa R, Ohtsuka T, Kageyama R, Hashimoto N. Hes1 and Hes5 control the progenitor pool, intermediate lobe specification, and posterior lobe formation in the pituitary development. Mol Endocrinol 2007; 21: 1458–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ueharu H, Higuchi M, Nishimura N, Yoshida S, Shibuya S, Sensui K, Kato T, Kato Y. Expression of Krüppel-like factor 6, KLF6, in rat pituitary stem/progenitor cells and its regulation of the PRRX2 gene. J Reprod Dev 2014; 60: 304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brinkmeier ML, Gordon DF, Dowding JM, Saunders TL, Kendall SK, Sarapura VD, Wood WM, Ridgway EC, Camper SA. Cell-specific expression of the mouse glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit gene requires multiple interacting DNA elements in transgenic mice and cultured cells. Mol Endocrinol 1998; 12: 622–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okuda T, van Deursen J, Hiebert SW, Grosveld G, Downing JR. AML1, the target of multiple chromosomal translocations in human leukemia, is essential for normal fetal liver hematopoiesis. Cell 1996; 84: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoi CS, Lee SE, Lu SY, McDermitt DJ, Osorio KM, Piskun CM, Peters RM, Paus R, Tumbar T. Runx1 directly promotes proliferation of hair follicle stem cells and epithelial tumor formation in mouse skin. Mol Cell Biol 2010; 30: 2518–2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaneko KJ, Kohn MJ, Liu C, DePamphilis ML. Transcription factor TEAD2 is involved in neural tube closure. Genesis 2007; 45: 577–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Medvedev S, Pan H, Schultz RM. Absence of MSY2 in mouse oocytes perturbs oocyte growth and maturation, RNA stability, and the transcriptome. Biol Reprod 2011; 85: 575–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bell SE, Sanchez MJ, Spasic-Boskovic O, Santalucia T, Gambardella L, Burton GJ, Murphy JJ, Norton JD, Clark AR, Turner M. The RNA binding protein Zfp36l1 is required for normal vascularisation and post-transcriptionally regulates VEGF expression. Dev Dyn 2006; 235: 3144–3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davidson D. The function and evolution of Msx genes: pointers and paradoxes. Trends Genet 1995; 11: 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Satoh K, Ginsburg E, Vonderhaar BK. Msx-1 and Msx-2 in mammary gland development. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2004; 9: 195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kioussi C, Carrière C, Rosenfeld MG. A model for the development of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis: transcribing the hypophysis. Mech Dev 1999; 81: 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li S, Crenshaw EB, 3rd, Rawson EJ, Simmons DM, Swanson LW, Rosenfeld MG. Dwarf locus mutants lacking three pituitary cell types result from mutations in the POU-domain gene pit-1. Nature 1990; 347: 528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tremblay JJ, Lanctôt C, Drouin J. The pan-pituitary activator of transcription, Ptx1 (pituitary homeobox 1), acts in synergy with SF-1 and Pit1 and is an upstream regulator of the Lim-homeodomain gene Lim3/Lhx3. Mol Endocrinol 1998; 12: 428–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suh H, Gage PJ, Drouin J, Camper SA. Pitx2 is required at multiple stages of pituitary organogenesis: pituitary primordium formation and cell specification. Development 2002; 129: 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou H, Yoshioka T, Nathans J. Retina-derived POU-domain factor-1: a complex POU-domain gene implicated in the development of retinal ganglion and amacrine cells. J Neurosci 1996; 16: 2261–2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmidt K, Schinke T, Haberland M, Priemel M, Schilling AF, Mueldner C, Rueger JM, Sock E, Wegner M, Amling M. The high mobility group transcription factor Sox8 is a negative regulator of osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Biol 2005; 168: 899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haslinger A, Schwarz TJ, Covic M, Lie DC. Expression of Sox11 in adult neurogenic niches suggests a stage-specific role in adult neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci 2009; 29: 2103–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhattaram P, Penzo-Méndez A, Sock E, Colmenares C, Kaneko KJ, Vassilev A, Depamphilis ML, Wegner M, Lefebvre V. Organogenesis relies on SoxC transcription factors for the survival of neural and mesenchymal progenitors. Nat Commun 2010; 1: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.