Abstract

The aim of the present study was to identify potential therapeutic targets for lung cancer and explore underlying molecular mechanisms of its development and progression. The gene expression profile datasets no. GSE3268 and GSE19804, which included five and 60 pairs of tumor and normal lung tissue specimens, respectively, were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between lung cancer and normal tissues were identified, and gene ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis of the DEGs was performed. Furthermore, protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks and a transcription factor (TF) regulatory network were constructed and key target genes were screened. A total of 466 DEGs were identified, and the PPI network indicated that IL-6 and MMP9 had key roles in lung cancer. A PPI module containing 34 nodes and 547 edges was obtained, including PTTG1. The TF regulatory network indicated that TFs of FOSB and LMO2 had a key role. Furthermore, MMP9 was indicated to be the target of FOSB, while PTTG1 was the target of LMO2. In conclusion, the bioinformatics analysis of the present study indicated that IL-6, MMP9 and PTTG1 may have key roles in the progression and development of lung cancer and may potentially be used as biomarkers or specific therapeutic targets for lung cancer.

Keywords: lung cancer, protein-protein interaction network, differentially expressed gene

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies and has a significant socioeconomic impact on patients and their families (1). In western countries, the mortality rate of lung cancer is 15% and the worldwide mortality rate for patients with lung cancer is 86% (2). The high mortality of lung cancer is mainly attributable to the lack of effective therapeutic methods and the difficulty of obtaining an early diagnosis. Thus, the development of effective therapeutic targets is urgently required.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) have been reported to have important roles in lung cancer, and their identification may aid in the elucidation of its underlying molecular mechanisms as well as the discovery of novel biomarkers and treatments (3). Numerous genes, including p53 (3,4), EGFR (5,6), kRAS (7), PIK3CA (8) and EML4 (9), are known to be associated with lung cancer, while others have remained elusive. Futhermore, SEMA5A and -6A were identified as potential therapeutic targets for lung cancer (10–12). Although tremendous efforts have been made to discover novel targets for lung cancer treatments, the current knowledge is insufficient and requires expansion.

In the present study, DEGs between lung cancer and normal lung tissues were identified. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) and transcription factor (TF) regulatory networks were constructed and key target genes were screened. Through the identification of key genes, the possible underlying molecular mechanisms as well as potential candidate biomarkers and treatment targets for lung cancer were explored.

Materials and methods

Affymetrix microarray data

The gene expression profile dataset no. GSE3268 deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) by Wachi et al (13) based on the GPL96 platform (HG-U133A; Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array), was subjected to bioinformatics analysis in the present study. The dataset contained a total of 10 chips, including five squamous cell lung cancer tissues and five paired adjacent normal lung tissues obtained from patients with squamous cell lung cancer.

Furthermore, the gene expression profile dataset GSE19804 based on the platform GPL570 (HG-U133_Plus_2; Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array), which was deposited in the GEO database by Lu et al (14), was used. The dataset contained 120 chips, including 60 samples of non-small cell lung cancer tissues and 60 samples of paired normal lung tissues from female Taiwanese patients.

Identification of DEGs

The raw data were pre-processed using the Affy package (15) in R language. DEGs of GSE3268 (DEG1) and GSE19804 (DEG2) between normal groups and disease groups were respectively analyzed using the limma package in R (16). Fold changes (FCs) in the expression of individual genes were calculated and DEGs with P<0.05 and |log FC| >1 were considered to be significant. DEG1 and DEG2 were then combined and the pooled dataset was referred to as the overlapping DEGs in the present study.

Gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs

GO analysis is a commonly used approach for functional studies of large-scale transcriptomic data (17). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database (18) contains information on networks of molecules or genes. The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (19) was used to systematically extract biological information from the large number of genes. GO functions and KEGG pathways of the overlapping DEGs were analyzed using DAVID 6.7 with P<0.05.

Construction of PPI network and screening of modules

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) (20) database was used to retrieve the predicted interactions for the DEGs; version 9.1 of STRING covers 1,133 completely sequenced species. All associations obtained in STRING are provided with a confidence score, which represents a rough estimate of the likelihood of a given association to describe a functional linkage between two proteins (21). The overlapping DEGs with a confidence score >0.4 were selected to construct the PPI network using Cytoscape software (version 3.0; http://cytoscape.org/) (22). Cytoscape allows for the visualization of complex networks and their integration to any type of attribute data. The MCODE (23) plugin in Cytoscape was used to divide the PPI into modules. GO functional analysis of genes in the modules was performed using the BinGo 2.44 plugin in Cytoscape (24) with a threshold of P<0.05 using the hypergeometric test.

Transcriptional regulatory network construction

The University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSC) database (http://genome.ucsc.edu) contains information on TF binding sites and the regulated genes (25). Using information collected from the UCSC database, DEGs were matched with their associated TFs. The TF regulatory network then was constructed using Cytoscape software (26).

Results

GO and pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs

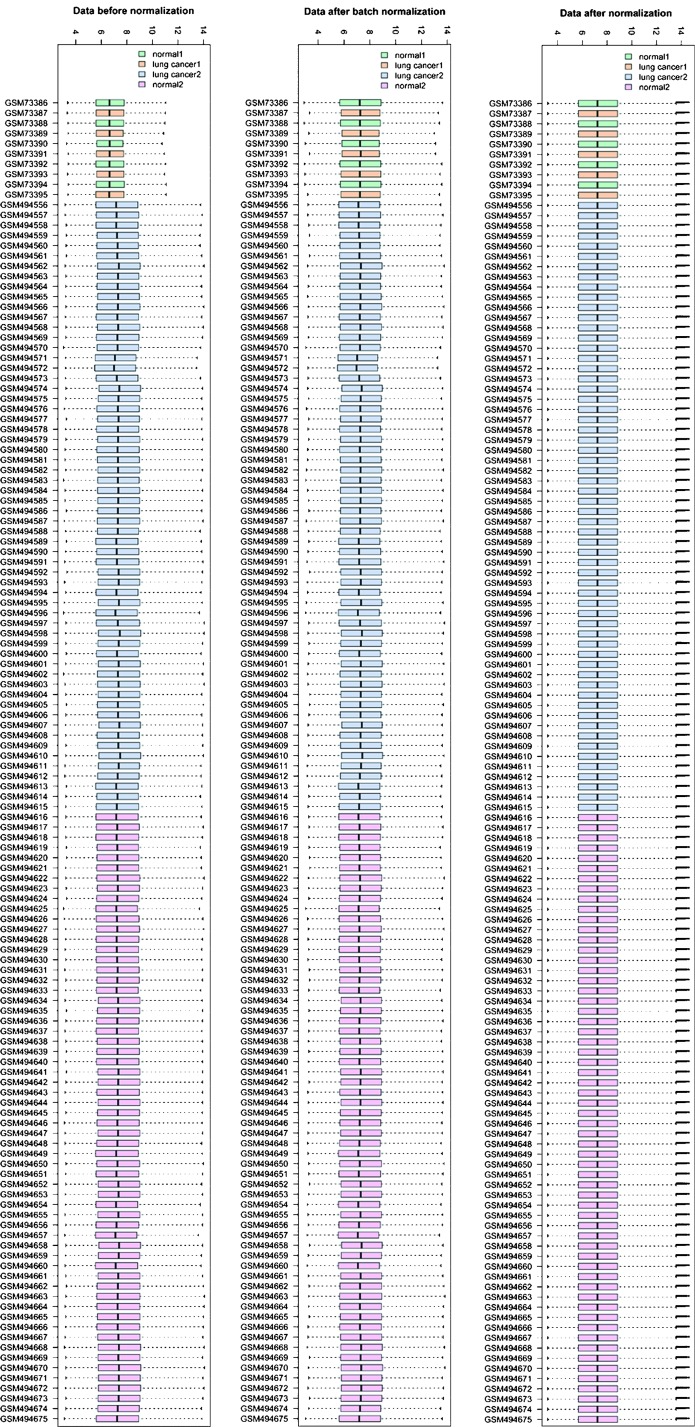

From the GEO datasets, information on the expression of 8,172 genes was obtained. The normalized results showed that the expression median after normalization was in a straight line (Fig. 1). A total of 466 DEGs, including 156 upregulated and 310 downregulated genes, were selected.

Figure 1.

Boxplot of normalized expression values for the datasets. The dotted lines in the middle of each box represent the median of each sample, and its distribution among samples indicates the level of normalization of the data, with a nearly straight line indicating a fair normalization level. Gene expression omnibus datasets: 1, GSE3268; 2, GSE19804.

Results of GO analysis showed that the upregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in biological processes, including collagen metabolic processes, multicellular organismal macromolecule metabolic processes and nuclear division (Table I); the downregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in biological processes, including response to wounding, immune response, defense response and inflammatory response (Table I).

Table I.

GO and pathway analysis of the differentially expressed genes.

| Expression | Category | Term/gene and function | Count | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04110 - Cell cycle | 12 | 6.94×10−7 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04512 - ECM-receptor interaction | 10 | 1.50×10−6 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04510 - Focal adhesion | 10 | 1.42×10−3 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04115 - p53 signaling pathway | 6 | 2.14×10−3 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa00240 - Pyrimidine metabolism | 5 | 3.93×10−2 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0032963 - Collagen metabolic process | 9 | 2.10×10−10 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0044259 - Multicellular organismal macromolecule metabolic process | 9 | 5.19×10−10 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0000280 - Nuclear division | 17 | 5.79×10−10 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0007067 - Mitosis | 17 | 5.79×10−10 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0000278 - Mitotic cell cycle | 21 | 7.04×10−10 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0000087 - M phase of mitotic cell cycle | 17 | 7.55×10−10 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005576 - Extracellular region | 53 | 1.41×10−10 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005578 - Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | 19 | 7.80×10−9 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0031012 - Extracellular matrix | 19 | 2.50×10−8 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0044421 - Extracellular region part | 30 | 2.27×10−7 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005819 - Spindle | 12 | 4.55×10−7 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0004222 - Metalloendopeptidase activity | 9 | 9.37×10−6 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0048407 - Platelet-derived growth factor binding | 4 | 1.53×10−4 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0004175 - Endopeptidase activity | 13 | 3.80×10−4 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0004857 - Enzyme inhibitor activity | 11 | 3.81×10−4 | |

| Downregulated | KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04060 - Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 20 | 6.99×10−5 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04610 - Complement and coagulation cascades | 8 | 2.47×10−3 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04062 - Chemokine signaling pathway | 13 | 4.53×10−3 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04650 - Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 10 | 9.69×10−3 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04614 - Renin-angiotensin system | 4 | 1.01×10−2 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0009611 - Response to wounding | 48 | 2.23×10−17 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0006952 - Defense response | 46 | 1.66×10−13 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0006954 - Inflammatory response | 33 | 2.92×10−13 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0006955 - Immune response | 43 | 4.20×10−10 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0048545 - Response to steroid hormone stimulus | 21 | 3.81×10−9 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005615 - Extracellular space | 55 | 2.36×10−18 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0044421 - Extracellular region part | 64 | 2.03×10−17 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005576 - Extracellular region | 93 | 3.37×10−15 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005886 - Plasma membrane | 131 | 2.25×10−12 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005887 - Integral to plasma membrane | 61 | 1.99×10−11 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0019838 - Growth factor binding | 16 | 2.01×10−9 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0030246 - Carbohydrate binding | 27 | 7.86×10−9 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0019955 - Cytokine binding | 13 | 1.54×10−6 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005509 - Calcium ion binding | 39 | 1.04×10−5 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0030247 - Polysaccharide binding | 14 | 1.11×10−5 |

BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function; Count, numbers of differentially expressed genes; ECM, extracellular matrix; GO, gene ontology; hsa, Homo sapiens; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; FAT, functional annotation tool.

Pathway analysis showed that the upregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in cell cycle, extracellular matrix - receptor interaction and the p53 signaling pathway (Table I); the downregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in cytokine receptor interaction, complement and coagulation cascades as well as chemokine signaling pathways (Table I).

Construction of PPI network and screening of module

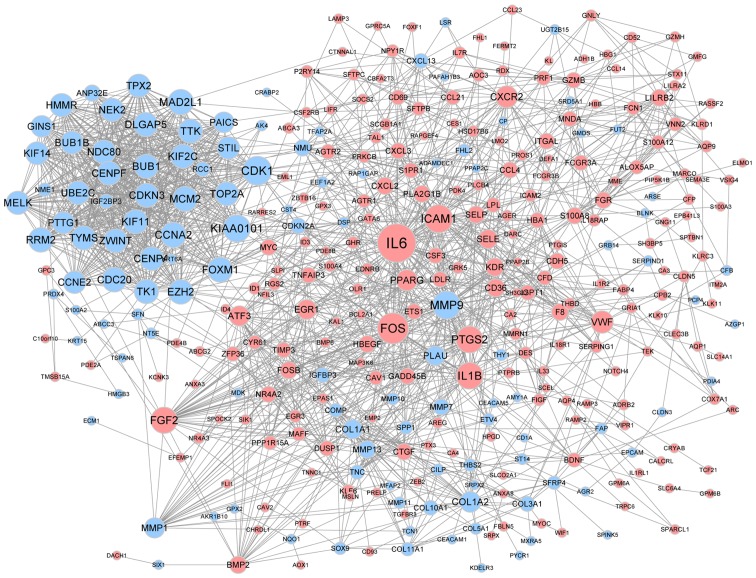

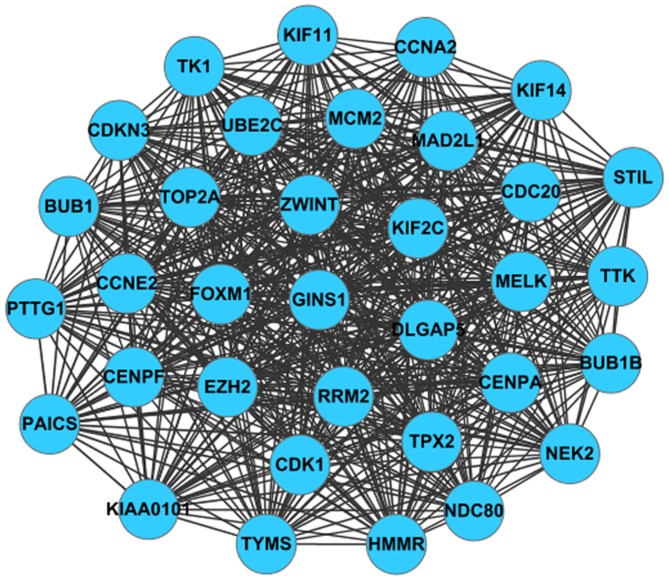

The PPI network was constructed based on the predicted interactions of the identified DEGs (Fig. 2). Genes of IL-6, FOSB, CDK1, MMP9 and ICAM1 were found to have a high degree of interaction in lung cancer. A sub-network containing 34 nodes and 547 edges was screened from the PPI network, such as PTTG1 (Fig. 3). The DEGs in the sub-net were significantly enriched in biological processes, such as the cell cycle, and pathway analysis showed that they were significantly enriched in cell cycle and oocyte meiosis (Table II).

Figure 2.

Protein-protein interaction network of the DEGs. Blue nodes represent products of upregulated DEGs and pink nodes represent products of down-regulated DEGs. The size of each node is proportional to the degree of nodes. DEG, differentially expressed gene.

Figure 3.

Sub-network screened from protein-protein interaction network. Nodes refer to the products of upregulated differentially expressed genes.

Table II.

GO and pathway analysis of genes in sub-network.

| Category | Term/gene and function | Count | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04110 - Cell cycle | 10 | 1.09×10−11 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04114- Oocyte meiosis | 6 | 1.09×10−5 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04914 - Progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation | 4 | 1.83×10−3 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04115 - p53 signaling pathway | 3 | 1.65×10−3 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa00240 - Pyrimidine metabolism | 3 | 3.10×10−2 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0000278 - Mitotic cell cycle | 19 | 7.13×10−21 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0007049 - Cell cycle | 22 | 1.65×10−19 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0000280 - Nuclear division | 16 | 2.14×10−19 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0007067 - Mitosis | 16 | 2.14×10−19 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0000087 - M phase of mitotic cell cycle | 16 | 2.82×10−19 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005819 - Spindle | 12 | 9.20×10−15 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0000777 - Condensed chromosome kinetochore | 8 | 3.94×10−11 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0015630 - Microtubule cytoskeleton | 14 | 5.31×10−11 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0000779 - Condensed chromosome, centromeric region | 8 | 1.01×10−10 |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0000922 - Spindle pole | 7 | 1.01×10−10 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005524 - Adenosine triphosphate binding | 15 | 4.89×10−7 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0032559 - Adenyl ribonucleotide binding | 15 | 5.78×10−7 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0030554 - Adenyl nucleotide binding | 15 | 1.10×10−6 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0001883 - Purine nucleoside binding | 15 | 1.32×10−6 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0001882 - Nucleoside binding | 15 | 1.44×10−6 |

BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function; Count, numbers of DEGs; GO, gene ontology; hsa, Homo sapiens; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; FAT, functional annotation tool.

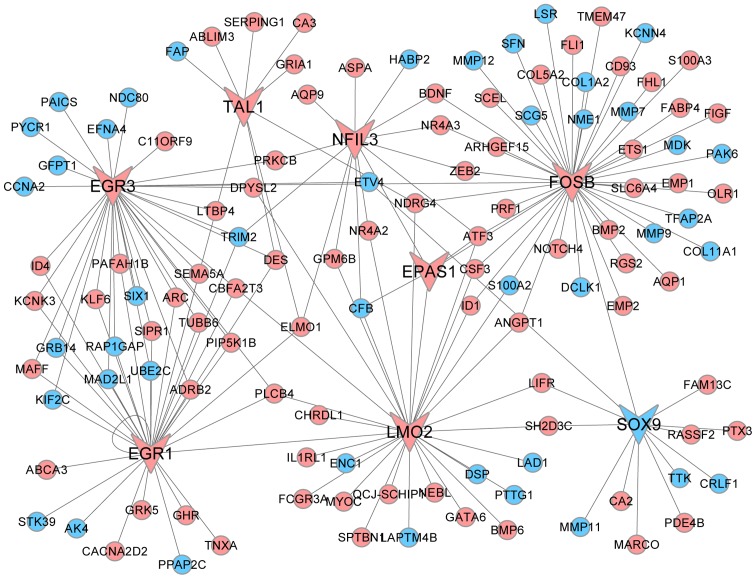

TF-target gene regulatory network analysis

Associations between 44 TFs and their 47 target DEGs were collected from the TF regulatory network (Fig. 4). TFs of FOSB and LMO2, which exhibited a high degree of interaction, were selected from this network. Furthermore, the results also showed that MMP9 was the target of FOSB and PTTG1 was the target of LMO2.

Figure 4.

Transcriptional regulatory network analysis. Blue nodes represent products of upregulated DEGs and pink nodes represent products of downregu-lated DEGs. Triangle arrowheads indicate transcription factors and circles indicate target genes. DEG, differentially expressed gene.

Discussion

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-associated mortality; however, the underlying molecular mechanisms of its development and progression have remained to be fully elucidated (1). The present study used a bioinformatics approach to predict the potential therapeutic targets and explore the possible molecular mechanisms for lung cancer. A total of 466 DEGs between tumorous and normal tissues was identified, among which 310 genes were downregulated and 156 were upregulated. By constructing a PPI network and a TF regulatory network, key genes, including IL6, MMP9 and PTTG1, were identified.

IL-6 is a multifunctional cytokine that was characterized as a regulator of immune and inflammatory responses (27,28). It is involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, survival and metabolism, and IL-6 signaling has an important role in tumorigenesis (29). Chung et al (30) found that IL-6 activated PI3K, which promoted apoptosis in human prostate cancer cell lines. Furthermore, studies have shown that IL-6 inhibited the growth of numerous types of cancer, including lung (31), breast (32) and prostate cancer (33). In the present study, IL-6 was shown to be downregulated in squamous cell and non-small cell lung cancer, and GO analysis showed that IL-6 was significantly enriched in biological processes, including defense response, inflammatory response, immune response and regulation of cell proliferation, which was consistent with a previous study (29). Combined with the above studies, it is indicated that IL-6 may be a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target in lung cancer.

MMP9 has a key role in cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis, apoptosis and host defense (34). Dysregulatoin of MMPs has been implicated in numerous diseases, including chronic ulcers and cancer (35–37). Downregulation of MMPs has been shown to inhibit metastasis, while upregulation of MMPs led to enhanced cancer cell invasion (37). In the present study, MMP9 was overexpressed and regulated by FOSB in lung cancer tissues. Kim et al (38) found that FOSB was downregulated in pancreatic cancer and promoted tumor progression. Kataoka et al (39) found that FOSB gene expression in cancer stroma is a independent prognostic indicator for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer receiving standard therapy. Combined with the above studies, the present study indicated that MMP9 may have important roles in the progression of lung cancer, and that it may be utilized as a therapeutic target.

PTTG1 has tumorigenic activity and is highly expressed in various tumor types (40). Studies have shown that PTTG1 was overexpressed in esophageal cancer and associated with endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer (41,42). Yoon et al (40) showed that the PTTG1 oncogene promoted tumor malignancy via epithelial-to-mesenchymal expansion of the cancer stem cell population. Hamid et al (43) found that PTTG1 promoted tumorigenesis in human embryonic kidney cells. A study by Li et al (44) indicated that PTTG1 promoted migration and invasion of human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Panguluri et al (45) showed that PTTG1 was an important target gene for ovarian cancer therapy. In the present study, PTTG1 was found to be overexpressed in lung cancer tissues and regulated by LMO2. LMO2 is an important regulator in determining cell fate and controlling cell growth and differentiation (46). Nakata et al (47) found that LMO2 was a novel predictive biomarker with the potential to enhance the accuracy of prognoses for pancreatic cancer. Yamada et al (48) showed that LMO2 is a key regulator of tumour angiogenesis. Combined with the above studies, the present study indicated that PTTG1 may have important roles in the progression of lung cancer and that it may represent a therapeutic target.

In conclusion, the bioinformatics analysis of the present study indicated that IL-6, MMP9 and PTTG1 may have key roles in the progression and development of lung cancer. They may be used as prognostic biomarkers as well as specific therapeutic targets for the treatment of lung cancer. However, molecular biology experiments are required to confirm these findings.

References

- 1.Nugent M, Edney B, Hammerness PG, Dain BJ, Maurer LH, Rigas JR. Non-small cell lung cancer at the extremes of age: Impact on diagnosis and treatment. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:193–197. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(96)00745-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang SP, Luh KT, Kuo SH, Lin CC. Chronological observation of epidemiological characteristics of lung cancer in Taiwan with etiological consideration-a 30-year consecutive study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1984;14:7–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andriani F, Roz E, Caserini R, Conte D, Pastorino U, Sozzi G, Roz L. Inactivation of both FHIT and p53 cooperate in deregulating proliferation-related pathways in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:631–642. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318244aed0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toyooka S, Tsuda T, Gazdar AF. The TP53 gene, tobacco exposure and lung cancer. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:229–239. doi: 10.1002/humu.10177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, Nomura M, Suzuki M, Wistuba II, Fong KM, Lee H, Toyooka S, Shimizu N, et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:339–346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin P, Kelly CM, Carney D. Epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted agents for lung cancer. Cancer Control. 2006;13:129–140. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, Goddard AD, Heldens SL, Herbst RS, Ince WL, Jänne PA, Januario T, Johnson DH, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5900–5909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto H, Shigematsu H, Nomura M, Lockwood WW, Sato M, Okumura N, Soh J, Suzuki M, Wistuba II, Fong KM, et al. PIK3CA mutations and copy number gains in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6913–6921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong DW, Leung EL, So KK, Tam IY, Sihoe AD, Cheng LC, Ho KK, Au JS, Chung LP, Pik Wong M, et al. The EML4-ALK fusion gene is involved in various histologic types of lung cancers from nonsmokers with wild-type EGFR and KRAS. Cancer. 2009;115:1723–1733. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro-Rivera E, Ran S, Thorpe P, Minna JD. Semaphorin 3B (SEMA3B) induces apoptosis in lung and breast cancer, whereas VEGF165 antagonizes this effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11432–11437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403969101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomizawa Y, Sekido Y, Kondo M, Gao B, Yokota J, Roche J, Drabkin H, Lerman MI, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, et al. Inhibition of lung cancer cell growth and induction of apoptosis after reex-pression of 3p21. 3 candidate tumor suppressor gene SEMA3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13954–13959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231490898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brambilla E, Constantin B, Drabkin H, Roche J. Semaphorin SEMA3F localization in malignant human lung and cell lines: A suggested role in cell adhesion and cell migration. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:939–950. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64962-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wachi S, Yoneda K, Wu R. Interactome-transcriptome analysis reveals the high centrality of genes differentially expressed in lung cancer tissues. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4205–4208. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu TP, Tsai MH, Lee JM, Hsu CP, Chen PC, Lin CW, Shih JY, Yang PC, Hsiao CK, Lai LC, et al. Identification of a novel biomarker, SEMA5A, for non-small cell lung carcinoma in nonsmoking women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2590–2597. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA. Affy-analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hulsegge I, Kommadath A, Smits MA. Globaltest and GOEAST: Two different approaches for Gene Ontology analysis. BMC Proc. 2009;3(Suppl 4):S10. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-s4-s10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogata H, Goto S, Sato K, Fujibuchi W, Bono H, Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:29–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: Database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-5-p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Lin J, Minguez P, Bork P, von Mering C, et al. STRING v9.1: Protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D808–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, Doerks T, Stark M, Muller J, Bork P, et al. The STRING database in 2011: Functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohl M, Wiese S, Warscheid B. Cytoscape: Software for visualization and analysis of biological networks. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;696:291–303. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-987-1_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maere S, Heymans K, Kuiper M. BiNGO: A cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wingender E, Dietze P, Karas H, Knüppel R. TRANSFAC: A database on transcription factors and their DNA binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:238–241. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schafer ZT, Brugge JS. IL-6 involvement in epithelial cancers. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3660–3663. doi: 10.1172/JCI34237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kishimoto T. Interleukin-6: From basic science to medicine-40 years in immunology. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hodge DR, Hurt EM, Farrar WL. The role of IL-6 and STAT3 in inflammation and cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2502–2512. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung TD, Yu JJ, Kong TA, Spiotto MT, Lin JM. Interleukin-6 activates phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase, which inhibits apoptosis in human prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate. 2000;42:1–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(20000101)42:1<1::AID-PROS1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takizawa H, Ohtoshi T, Ohta K, Yamashita N, Hirohata S, Hirai K, Hiramatsu K, Ito K. Growth inhibition of human lung cancer cell lines by interleukin 6 in vitro: A possible role in tumor growth via an autocrine mechanism. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4175–4181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knüpfer H, Preiss R. Significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6) in breast cancer (review) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giri D, Ozen M, Ittmann M. Interleukin-6 is an autocrine growth factor in human prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:2159–2165. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sica A, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Cancer related inflammation: The macrophage connection. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benveniste EN. Role of macrophages/microglia in multiple sclerosis and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Mol Med (Berl) 1997;75:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s001090050101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coussens LM, Fingleton B, Matrisian LM. Matrix metal-loproteinase inhibitors and cancer: Trials and tribulations. Science. 2002;295:2387–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JH, Lee JY, Lee KT, Lee JK, Lee KH, Jang KT, Heo JS, Choi SH, Rhee JC. RGS16 and FosB underexpressed in pancreatic cancer with lymph node metastasis promote tumor progression. Tumor Biol. 2010;31:541–548. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kataoka F, Tsuda H, Arao T, Nishimura S, Tanaka H, Nomura H, Chiyoda T, Hirasawa A, Akahane T, Nishio H, et al. EGRI and FOSB gene expressions in cancer stroma are independent prognostic indicators for epithelial ovarian cancer receiving standard therapy. Gene Chromosome Cancer. 2012;51:300–312. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoon CH, Kim MJ, Lee H, Kim RK, Lim EJ, Yoo KC, Lee GH, Cui YH, Oh YS, Gye MC, et al. PTTG1 oncogene promotes tumor malignancy via epithelial to mesenchymal transition and expansion of cancer stem cell population. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19516–19527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.337428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibata Y, Haruki N, Kuwabara Y, Nishiwaki T, Kato J, Shinoda N, Sato A, Kimura M, Koyama H, Toyama T, et al. Expression of PTTG (pituitary tumor transforming gene) in esophageal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002;32:233–237. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyf058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghayad SE, Vendrell JA, Bieche I, Spyratos F, Dumontet C, Treilleux I, Lidereau R, Cohen PA. Identification of TACC1, NOV and PTTG1 as new candidate genes associated with endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer. J Mol Endocrinol. 2009;42:87–103. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamid T, Malik MT, Kakar SS. Ectopic expression of PTTG1/securin promotes tumorigenesis in human embryonic kidney cells. Mol Cancer. 2005;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Yin C, Zhang B, Sun Y, Shi L, Liu N, Liang S, Lu S, Liu Y, Zhang J, et al. PTTG1 promotes migration and invasion of human non-small cell lung cancer cells and is modulated by miR-186. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2145–2155. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panguluri SK, Yeakel C, Kakar SS. PTTG: An important target gene for ovarian cancer therapy. J Ovarian Res. 2008;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma S, Guan XY, Beh PS, Wong KY, Chan YP, Yuen HF, Vielkind J, Chan KW. The significance of LMO2 expression in the progression of prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2007;211:278–285. doi: 10.1002/path.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakata K, Ohuchida K, Nagai E, Hayashi A, Miyasaka Y, Kayashima T, Yu J, Aishima S, Oda Y, Mizumoto K, et al. LMO2 is a novel predictive marker for a better prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Neoplasia. 2009;11:712–719. doi: 10.1593/neo.09418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamada Y, Pannell R, Forster A, Rabbitts TH. The LIM-domain protein Lmo2 is a key regulator of tumour angiogenesis: A new anti-angiogenesis drug target. Oncogene. 2002;21:1309–1315. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]