Abstract

Objective

To determine the reliability of Internet-based information on community-based weight-loss programs and grade their degree of concordance with 2013 American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society weight management guidelines.

Methods

We conducted an online search for weight-loss programs in the Maryland-Washington, DC-Virginia corridor. We performed content analysis to abstract program components from their websites, and then randomly selected 80 programs for a telephone survey to verify this information. We determined reliability of Internet information in comparison with telephone interview responses.

Results

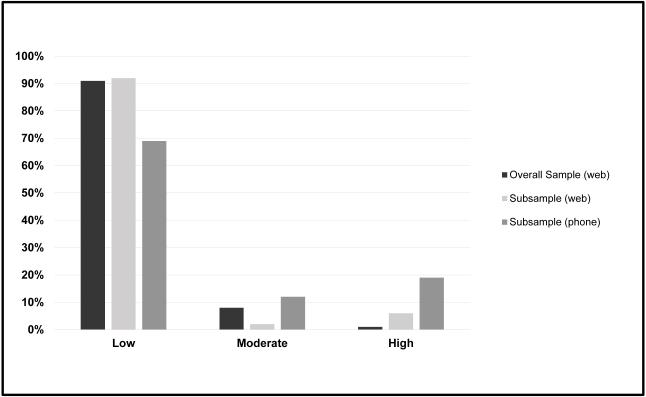

Of the 191 programs, we graded 1% as high, 8% as moderate, and 91% as low with respect to guideline concordance based on website content. Fifty-two programs participated in the telephone survey (65% response rate). Program intensity, diet, physical activity, and use of behavioral strategies were underreported on websites as compared to description of these activities during phone interview. Within our subsample, we graded 6% of programs as high based on website information, whereas we graded 19% as high after telephone interview.

Conclusions

Most weight-loss programs in an urban, mid-Atlantic region do not currently offer guideline-concordant practices and fail to disclose key information online, which may make clinician referrals challenging.

Keywords: weight loss, Internet information

Introduction

Two-thirds of U.S. adults are overweight or obese (1), and excess body weight increases the risk of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus among many other comorbidities (2). Studies have demonstrated that losing weight can prevent the development of these conditions including hypertension and diabetes (3-4), and a 3 to 5% weight loss has been recommended (5). Obesity and its related conditions have been estimated to cost $147 billion annually (6).

Despite U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations for primary care providers (PCPs) to counsel their obese patients to lose weight, patients have not reported increased receipt of weight-loss counseling (7). PCPs have cited a number of barriers to this counseling including lack of time, inadequate training, and pessimism regarding weight loss (8). Recent guidelines on weight management published by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society (AHA/ACC/TOS) recommended that clinicians refer obese patients to high intensity, comprehensive lifestyle interventions by a trained interventionist (5). These programs should include: 1) a moderately reduced calorie diet; 2) increased physical activity; and 3) use of behavioral strategies to facilitate adherence to recommendations. However, it is unclear how many weight-loss programs currently available in the community meet these evidence-based guidelines.

To identify guideline-concordant weight-loss programs, physicians and patients may turn to the Internet. Surveys indicate that both physicians and U.S. adults increasingly use the Internet for gathering health and medical information. Physician Internet use for medical information gathering has increased from 2.8 to 4 hours per week between 2009 and 2013 (9). In 2014, 87% of U.S. adults were identified as “Internet users;” 72% of whom had searched online for health information within the previous year (10). However, a prior study found that the quality of general weight-loss information online was suboptimal (11).

Our goal was to evaluate whether web-based information provided by community-based weight-loss centers reported their practices on key areas identified in the 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS weight management guidelines. We then compared this web-based information to information obtained through phone interview within a randomly selected sub-sample of programs.

Methods

Identification of community-based weight-loss programs

In June 2014, we conducted a systematic online search to identify community-based weight-loss programs that were located within a 10-mile radius of a large practice network of 17 primary care clinics in the Maryland-Washington, DC-Virginia corridor (Maryland: Baltimore City, Baltimore County, Anne Arundel County, Howard County, Prince George’s County, Montgomery County. Washington D.C. Virginia: Arlington County, Fairfax County, Alexandria). We searched Yellowpages.com and Yellowbook.com using the terms “overweight OR obesity OR weight management OR weight loss OR weight loss services” to identify centers located within 10 miles of each primary care clinic. We also searched Google Maps using the same search terms and identified centers located within the same zip code of each primary care clinic (distance search unavailable). We recorded the name, address, phone and website address (if available) for all identified centers. We then verified that the identified centers offered weight-loss services by reviewing their websites. We only included centers with valid website addresses that were currently offering a weight management program in the Maryland-Washington, DC-Virginia corridor in the final sample.

The Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB reviewed and exempted this study protocol as non-Human subjects research.

Data abstraction and grading of guideline concordance of programs’ websites

To determine the information available from all included programs’ websites, we performed a content analysis. Prior studies have used content analysis to examine visual portrayals of overweight and obesity in the U.S. media focusing on images associated with news articles and television series (12-14), and we adapted these strategies for this study. We captured all pages available from each program’s website between June 6 and June 11, 2014. We developed a coding scheme based upon 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS weight management guidelines (5) and prior reviews on efficacy of prescription medications and supplements for weight loss (15-16) to identify relevant content (Supporting Information S1). We considered supplements to include dietary supplements, nutraceuticals, or other products that are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the treatment of obesity (e.g., vitamins, minerals, herbal, botanicals, amino acids, enzymes, hormones, etc). Efficacy and safety of supplements vary (17). Two investigators independently (BB, AM) reviewed the pages from these websites to abstract this information from text and images. Discrepancies between the two coders were resolved through consensus adjudication by the third investigator (KG).

Using the information abstracted from their websites during content analysis, we evaluated each program based on five key components (Table 1) and then graded them on their degree of guideline concordance. We graded a program as “high” if the program met all five criteria; as “moderate” if the program did not report use of supplements and met at least two of the other four criteria; and as “low” if the program reported using supplements or met less than two of the other criteria. We report the frequencies of abstracted data elements and guideline concordance assessments for the overall sample.

Table 1.

Key Components in Assessing Guideline Concordance of Community-based Weight Loss Programs

| Component | Criteria for Guideline Concordance |

|---|---|

| Program Intensity | Reports offering a high intensity intervention (≥14 sessions in 6 months) |

| Dietary change | Reports recommending a moderate calorie deficit, using an evidence- based named dieta), and/or providing meal replacements |

| Physical activity | Reports encouraging increased physical activity of any type or duration |

| Behavior modification | Reports recommending regular self-monitoring of weight, meal planning, food tracking, and/or exercise tracking |

| Supplement use | Does not report dispensing or recommending supplementsb) |

Evidence-based named diets include those listed in 2013 weight management guidelines (8): European Association for the Study of Diabetes Guidelines, Higher protein, Higher Protein Zone ™, Lacto-ovo-vegetarian, Low calorie, Low carbohydrate, Low fat, Low fat vegan, Low glycemic load, Lower Fat, Macronutrient-targeted diets, Mediterranean style, Moderate protein, AHA-style 1 Step 1 diet.

Supplements include dietary supplements, nutraceuticals, or other products that are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the treatment of obesity (e.g., vitamins, minerals, herbal, botanicals, amino acids, enzymes, hormones, etc).

Validation subsample for telephone survey

We examined the reliability of information abstracted from the programs’ websites compared with information obtained during a telephone query. Using a computer program, we randomly selected 80 programs to participate in the telephone survey for this validation subsample. We created a survey instrument to capture the same elements contained in our content analysis abstraction form (Supporting Information S2). We called each randomized program to describe the study purpose and perform the interview with a staff representative if the program was willing to participate. We made at least 5 calls to a program before labeling them as a non-responder. Fifty-two programs completed the telephone survey (65% response rate with 6 refusals and 22 non-responders).

We compared the data obtained from the websites to the information gathered during the telephone interview using cross-tabulations in STATA (College Station, TX). We examined the reliability (reliable, misrepresentation, lacking representation) and calculated the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of program intensity, dietary change, physical activity, behavior modification, and supplement use. We considered information as “reliable” if information gathered from the website was the same as reported in the telephone interview; as “misrepresentation” if the program reported practices on the website that were not endorsed in the telephone interview; and “lacking representation” if the program endorsed practices in the telephone interview that were not reported on the website. We also compared the grading of guideline concordance using the website data to the grading of guideline concordance using the telephone data.

Results

We identified 191 community-based weight-loss programs that were operating and had active websites in our catchment area (Figure S1). In our sample, 29% of programs were physician supervised, 6% were affiliates of nationally available commercial weight-loss programs (e.g., Weight Watchers, Jenny Craig), and 5% were associated with a bariatric surgery practice. Nearly all programs were delivered in-person (96%).

Table 2 displays the frequency of reported elements on program websites. Only 59% of programs described their intensity, and only 17% overall could be identified as high-intensity programs that advised more than 14 sessions in a 6-month period. The majority of programs (75%) described dietary change as a part of their weight-loss program; however, the type of dietary change was often not specified. Most programs (57%) described increased physical activity as a part of their weight-loss program, but only 3% reported advising the recommended goal of 150 minutes or more of moderate physical activity per week. Only 53% of programs described using any behavioral strategies (e.g., self-monitoring of weight, tracking of food intake and/or exercise). Few programs reported prescribing FDA-approved medications (15%), yet 34% endorsed the use of supplements and 29% offered other alternative therapies (e.g., body wraps, infrared therapy, liposuction, etc.) for weight loss.

Table 2.

Frequency of Reported Elements on Community-based Weight Loss Program Websites as Obtained from Content Analysis

| Overall Sample (n=191) |

|

|---|---|

| Stipulated any program intensity | 59% |

| • Self-directed program | 31% |

| • High-intensity programa) | 17% |

| Recommended any dietary change | 75% |

| • Moderate calorie deficit | 10% |

| • Evidence-based named dietb) | 14% |

| • Meal replacements | 24% |

| Recommended any physical activity | 57% |

| • Advises ≥150 minutes activity per week | 3% |

| Used any behavior modification strategy | 53% |

| • Self-monitoring of weight | 15% |

| • Tracking food intake or meal planning | 45% |

| Prescribes FDA-approved weight loss medication(s) | 15% |

| • Phentermine | 3% |

| • Otherc) | 0 |

| Recommends/dispenses supplementsd) | 34% |

| • B12 injections | 17% |

| • hCG | 7% |

| • Green tea products | 3% |

| • “Fat burners” | 9% |

| Other alternative therapiese) | 29% |

Abbreviations: FDA – Food and Drug Administration; hCG – human chorionic gonadatropin.

High intensity program advises more than 14 sessions in 6 months.

Named diets as listed in footnote of Table 1.

At time of abstraction, other FDA-approved medications included Phentermine/Topiramate, Lorcaserin, and Orlistat.

Supplements include dietary supplements, nutraceuticals, or other products that are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the treatment of obesity (e.g., vitamins, minerals, herbal, botanicals, amino acids, enzymes, hormones, etc).

Alternative therapies include body wraps, infrared therapy, liposuction, body sculpting, acupuncture, and hypnosis.

With respect to guideline concordance within our overall sample, we graded 1% of programs as highly concordant, 8% as moderate, and 91% as low based on website content (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Grading of Guideline Concordance among Overall Sample and Subsample.

The overall sample includes website information from 191 programs. The subsample includes 52 programs that participated in a telephone interview, and information is reported by data source (website or phone). We assessed each program for 5 key elements as recommended in recent guidelines (5): high program intensity, use of evidence-based dietary strategy, recommendation for physical activity, use of any behavioral strategy, and avoidance of supplements. We graded a program as “high,” if the program met all five criteria; as “moderate,” if the program did not report use of supplements and met at least two of the other four criteria; and as “low,” if the program reported using supplements or met less than two of the other criteria.

Comparison of web-based information to telephone interviews

Out of the 80 programs randomly selected for inclusion in the subsample, representatives from 52 programs agreed to be interviewed (average length of employment of interviewee: 7 years, range 5 months to 23 years). In this subsample, 35% of programs were physician supervised, 12% were affiliates of nationally available commercial weight-loss programs, and 10% were associated with a bariatric surgery practice. Nearly all programs were delivered in-person (96%).

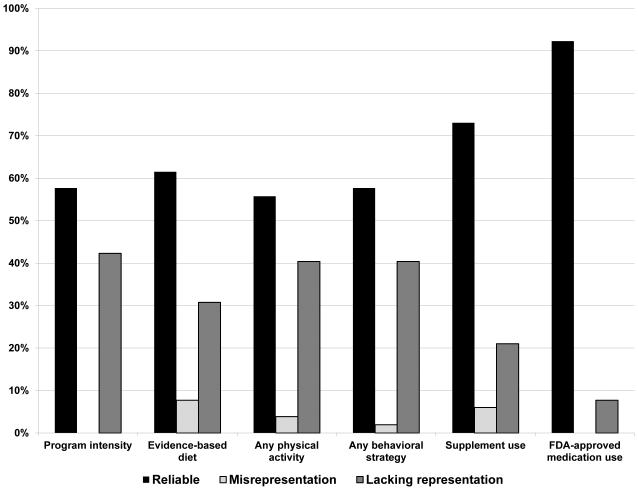

We compared the information provided on program websites to that obtained during telephone interviews to determine reliability of web-based information (Figure 2). Key elements including program intensity, physical activity, and use of behavioral strategies were reported reliably on less than 60% of programs’ websites. Program intensity, dietary change, physical activity and use of behavioral strategies were often not reported or were inadequately described on websites, although program contacts endorsed these activities and provided detailed descriptions during phone interview (lacking representation). In contrast, reported use of FDA-approved medications had a high degree of reliability (92%). Reported use of supplements also had a high degree of reliability, although 21% of program contacts endorsed use of these products during phone interview when the website did not mention their use (lacking representation). Table S1 contains calculations of sensitivity, specificity and predictive values for each key element.

Figure 2. Comparison of Elements Reported on Website with Information from Telephone Interview among Subsample.

A total of 52 programs agreed to participate in the telephone interview. We compared information from the website with that from the telephone interview. We labeled the information from each key element as reliable, if the information from website and telephone were the same. We labeled the information as misrepresentation, if the website reported the use of an element that was not endorsed via phone. We labeled the information as lacking representation, if the website failed to mention a practice that was endorsed during phone interview.

Within our subsample, we graded 6% of programs as high, 2% as moderate, and 92% as low with respect to guideline concordance based on website information (Figure 1). In contrast, we graded 19% of programs as high, 12% as moderate, and 69% as low guideline concordance based on information from telephone interviews.

Discussion

This is the first study to capture the breadth and quality of services offered by community-based weight-loss programs. Given that surveys have reported 29% to 48% of Americans are actively trying to lose weight (18-19) and recent guidelines promote referral to high-intensity, multi-component programs (5), our results suggest that few guideline-concordant weight-loss programs may currently be available in the urban, mid-Atlantic region (Internet: 1% rated as highly concordant within total sample; Phone: 19% rated as highly concordant within subsample). Our findings indicate that patients and clinicians in this area may have difficulties identifying community-based programs concordant with recent recommendations if they rely on information from the Internet. Most programs failed to represent key elements of program structure and content on their website such as program intensity, physical activity and use of behavioral strategies, which are essential in determining guideline concordance. We were able to obtain additional details regarding the services provided during phone interview. Therefore, clinicians planning to refer a patient to weight-loss services may need to consider calling to verify program details and assess guideline concordance prior to patient referral, although this practice may be difficult to implement during the typical primary care visit.

Website information was reliable with respect to use of FDA-approved weight-loss medication and use of supplements. Clinicians and patients can feel relatively confidant that if a website reports that a program uses FDA-approved medications that this is likely to be a part of their practice. Reported use of supplements on a website is also likely to represent that these products are a part of their practice; however, clinicians should remain somewhat cautious given that 21% of programs in the subsample endorsed using these products when this practice was not advertised online. Therefore, clinicians may consider discussing the overall evidence of benefits and risks of supplements for weight loss with their patients prior to referral to any community-based weight-loss program. Our definition of supplements included dietary supplements, nutraceuticals, or other products that are not approved by the FDA for obesity treatment; however, heterogeneity exists among the included products with respect to efficacy and safety. For example, ephedra may aid weight loss but has potentially harmful cardiovascular effects, while chitosan has no demonstrated weight loss effect (17). If a program uses supplements, clinicians may need to closely examine and verify which products are used given the variability in efficacy and safety.

Few studies have previously examined the validity of weight-loss information available on the Internet. However, our findings are consistent with one such study that concluded that most webpage content likely to be accessed by layperson Internet-users seeking weight-loss information was of suboptimal quality (11). Our findings also indicate that within the weight-loss services industry, detailed information regarding services offered is also limited.

In general, consumer protection laws are designed “to ensure that products or services are described truthfully online and that consumers understand what they are paying for” (20). The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regulates these practices in the U.S. The FTC has already created guidelines with respect to advertising claims by the weight-loss and supplement industries (21). Expanding this resource to also encourage or require weight-loss programs to disclose their practices online regarding key guideline-concordant elements may improve awareness of what services consumers are paying for, and thus enhance consumer protection practices. This may be particularly relevant to programs’ online content, given that patients and clinicians alike rely on the Internet for health information (9-10). Improved disclosure online would make it easier for clinicians to identify programs using the Internet alone, as we suspect that many will not have time available during appointments to call programs to verify their practices. Encouraging the disclosure of these key elements would help patients and clinicians to easily identify highly guideline concordant programs, as well as highlighting and possibly increasing referral to the 19% of such programs that we identified through phone verification. Additional oversight from regulatory agencies or perhaps guidelines from medical associations like The Obesity Society may be a potential mechanism to promote the adoption of better disclosure practices by community-based weight loss programs.

Our study has limitations. First, we only examined programs within the Maryland-Washington, DC-Virginia corridor, which may limit the generalizability of our results. It is unknown whether our findings might apply in rural settings or to other U.S. regions. Factors that vary with geographic location, such as travel distance or parking fees, might influence whether community-based programs can realistically expect participants to engage as frequently as recommended by the guidelines. Our strategy identified in-person programs within the community; therefore, we cannot comment whether our results apply to weight-loss programs delivered remotely by phone or Internet. In addition, our subsample included a higher percentage of programs that were physician-supervised (35% vs 29%), affiliates of nationally available commercial weight-loss programs (12% vs 6%), or associated with a bariatric surgery practice (10% vs 5%) as compared to the overall sample. These types of programs might have been more inclined to participate in the telephone survey and their practices may not represent the weight-loss community as a whole. For example, we rated 6% of the subsample as highly concordant based on their website information, where only 1% of the overall sample was graded as high. These differences between the subsample and overall sample may contribute to bias within the subsample. Second, we considered the information obtained by phone within our subsample to be a more accurate representation of program practices than information available online. The quality of this information may vary based on the degree of expertise of the individual being interviewed, although the average duration of employment for these individuals was 7 years. In addition, interviewee phone responses may be subject to social desirability bias. Third, we used an arbitration strategy with a third reviewer in our abstraction process, and therefore, we were unable to conduct an inter-rater reliability analysis. Future studies could consider examining inter-rater reliability to better validate the abstraction process. Finally, we did not capture information regarding program costs or insurance coverage, which may be important factors that patients and clinicians might desire from online information when making an informed decision regarding program referral.

Conclusion

In an urban, mid-Atlantic region, the majority of community-based weight-loss programs do not currently offer practices concordant with the 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guidelines and the failure to disclose key information online may make clinician referral to guideline concordant programs challenging. Given that only 19% of programs were rated as highly guideline-concordant based on information obtained during phone interviews, clinicians should be aware that few weight management programs might exist that meet the criteria recommended for consideration of patient referral. Our findings highlight the need for regulatory agencies to promote more complete and accurate disclosure of weight-loss program practices online. Until such disclosures are common, clinicians should consider calling weight-loss programs to verify what services are offered.

Supplementary Material

Study Importance Questions.

1. What is already known about this subject?

Guidelines recommend that clinicians refer obese patients to high intensity, comprehensive lifestyle interventions by a trained interventionist; however, it is unclear how such programs are currently available in the community.

Clinicians use the Internet for medical information gathering; however, the quality of general weight-loss information online is suboptimal.

2. What does your study add?

Our results suggest that few guideline-concordant weight-loss programs may currently be available within an urban area in the mid-Atlantic region.

Our findings might suggest that patients and clinicians could have difficulties identifying community-based programs concordant with recent recommendations if they rely on information from the Internet.

Highlights the need for regulatory agencies to promote more complete and accurate disclosure of weight-loss program practices online.

Acknowledgements

We thank the medical librarian, Victoria Riese, for her help with devising the search strategy to identify community-based weight-loss centers.

Funding

BB was supported by the Medical Student Research Program in Diabetes at Johns Hopkins University-University of Maryland Diabetes Research Center from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (P30DK079637). KAG was supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL116601).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Cause-specific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2007;298:2028–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, Elmer PJ, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2083–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study Lancet. 2009;374:1677–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, et al. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer and service specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w822–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felix H, West DS, Bursac Z. Impact of USPSTF practice guidelines on provider weight loss counseling as reported by obese patients. Prev Med. 2008;47:394–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. Do physician beliefs about causes of obesity translate into actionable issues on which physicians counsel their patients? Prev Med. 2013:326–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salinas GD. Trends In Physician Preferences for Use and Sources of Medical Information in Response to Questions Arising at the Point of Care: 2009-2013. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2014;34:S11–S16. doi: 10.1002/chp.21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pew Research Center. Pew Internet: health fact sheet 2015. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/health-fact-sheet. Accessed on 2/24/15.

- 11.Modave F, Shokar NK, Peñaranda E, Nguyen N. Analysis of the accuracy of weight loss information search engine results on the Internet. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1971–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gollust SE, Eboh I, Barry CL. Picturing Obesity: Analyzing the social epidemiology of obesity conveyed through US news media images. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74:1544–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heuer CA, McClure KJ, Puhl RM. Obesity Stigma in Online News: A Visual Content Analysis. Journal of Health Communication: International Perspectives. 2011;16(9):976–87. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.561915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg BS, Brownell KD, et al. Portrayals of Overweight and Obese Individuals on Commercial Television. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:342–1348. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term Drug Treatment for Obesity: A systematic and Clinical Review. JAMA. 2014;311:74–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poddar K, Cheskin LJ, et al. Nutraceutical Supplements for Weight Loss: A Systematic Review. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2011;26:539–52. doi: 10.1177/0884533611419859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Common dietary supplements for weight loss. American Family Physician. 2004;70:1731–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saad L. To lose weight, Americans rely more on dieting than exercise. Gallup Poll Social Series: Health and Healthcare; 2011. Accessed at www.gallup.com/poll/150986/Lose-Weight-Americans -Rely-Dieting-Exercise.aspx on 27 September 2014.

- 19.Yaemsiri S, Slining MM, Agarwal SK. Perceived weight status, overweight diagnosis, and weight control among US adults: the NHANES 2003-2008 study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:1063–70. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Federal Trade Commission .com disclosures: how to make effective disclosures in digital advertising. March 2013. Accessed at https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/press-releases/ftc-staff-revises-online-advertising-disclosure-guidelines/130312dotcomdisclosures.pdf on 15 September 2015.

- 21.Cleland RL, Gross WC, Koss LD, Daynard M, Muoio KM. Weight-loss advertising: an analysis of current trends. Federal Trade Commission Staff Report, September 2002. Accessed at https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/weight-loss-advertisingan-analysis-current-trends/weightloss_0.pdf on 27 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.