Abstract

Hypertension in pregnancy is a risk factor for future hypertension and cardiovascular disease. This may reflect an underlying familial predisposition or persistent damage caused by the hypertensive pregnancy. We sought to isolate the effect of hypertension in pregnancy by comparing the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease in women who had hypertension in pregnancy and their sisters who did not using the dataset from the Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy study, which examined the genetics of hypertension in white, black, and Hispanic siblings. This analysis included all sibships with at least one parous woman and at least one other sibling. After gathering demographic and pregnancy data, BP and serum analytes were measured. Disease-free survival was examined using Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards regression. Compared with their sisters who did not have hypertension in pregnancy, women who had hypertension in pregnancy were more likely to develop new onset hypertension later in life, after adjusting for body mass index and diabetes (hazard ratio 1.75, 95% confidence interval 1.27–2.42). A sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy was also associated with an increased risk of hypertension in brothers and unaffected sisters, whereas an increased risk of cardiovascular events was observed in brothers only. These results suggest familial factors contribute to the increased risk of future hypertension in women who had hypertension in pregnancy. Further studies are needed to clarify the potential role of nonfamilial factors. Furthermore, a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy may be a novel familial risk factor for future hypertension.

Keywords: hypertension, cardiovascular disease, pregnancy hypertension, stroke, familial predisposition

The American Heart Association recently recognized hypertension in pregnancy as a risk factor for coronary heart disease and stroke in women.1–3 Hypertension in pregnancy includes gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, and chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia. These conditions affect 8% of pregnancies.4 Women who have had hypertension in pregnancy are 1.5–2 times more likely to develop hypertension and cardiovascular disease later in life, compared with women who have had normotensive pregnancies.5,6 Cardiovascular event risk is further increased in women who have had more severe forms, including early onset, recurrent or superimposed preeclampsia.6,7 The mechanisms regulating this effect are an area of intense investigation. One possibility is that women who develop hypertension in pregnancy may have a familial predisposition to cardiovascular disease, which is unmasked by the physiologic stress of pregnancy.1 Of note, women who have had preeclampsia are more likely to have a family history of cardiovascular disease and hypertension.8 Alternatively, hypertension in pregnancy may cause lasting damage that ultimately leads to cardiovascular disease. Women with preeclampsia have cardiac impairment9 and vascular dysfunction,10,11 which persist post-partum.12,13 It is also possible that both factors may contribute. Women who develop hypertension in pregnancy may have an underlying familial predisposition to cardiovascular disease. The damage caused by hypertension in pregnancy could be the second hit that triggers cardiovascular events.

These hypotheses have important clinical implications for disease prevention in women who have had hypertension in pregnancy and their siblings. If the elevated disease risk is due to lasting damage caused by the hypertensive pregnancy, then clinicians may have a very small window of opportunity in which to prevent or reverse this damage. Screening tests would be needed to identify women at risk for persistent damage. Treatment goals for hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors in women with hypertension in pregnancy may need to be adjusted. If the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease is increased in siblings of women who have had hypertension in pregnancy, suggesting familial aggregation, then these men and women may benefit from early monitoring and prevention programs.

Sibling studies can provide valuable insights into these two potential mechanisms, as siblings share genetic and some environmental factors that affect cardiovascular risk. If hypertension in pregnancy causes lasting damage that increases long-term disease risk, then risk should be elevated in women who have had hypertension in pregnancy, but not in their sisters who had normotensive pregnancies. Alternatively, if hypertension in pregnancy identifies women with a familial predisposition to future disease, then disease risk should be elevated in both women who have had hypertension in pregnancy and in their unaffected sisters. A third possibility is that disease risk will be highest in women who have had hypertension in pregnancy, intermediate in unaffected sisters, and lowest in women from families in which no parous sister has had hypertension in pregnancy. This finding could suggest that both mechanisms contribute to the increased risk of future disease, or that women who develop hypertension in pregnancy have a stronger genetic predisposition to future disease or other risk factors, compared with their sisters who had normotensive pregnancies.

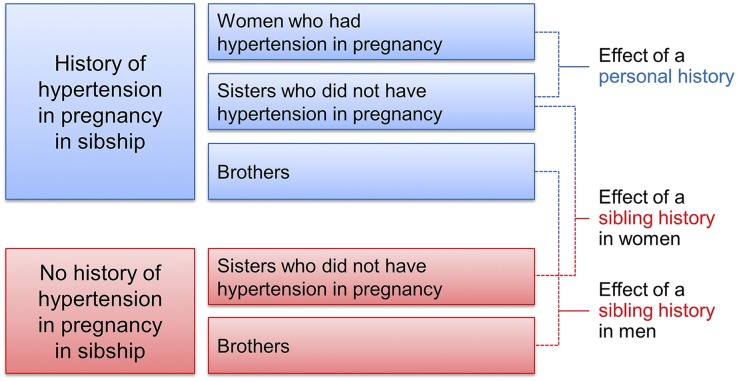

This study examined the effects of a personal and sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy on the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease using data from the Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) study. GENOA enrolled siblings from families with a high prevalence of hypertension or diabetes. We hypothesized that women who had hypertension in pregnancy would be more likely to develop hypertension and cardiovascular disease than their unaffected sisters (within-family comparison, Figure 1). We further posited that a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy would be a risk factor for hypertension and cardiovascular disease in brothers and unaffected sisters (comparison across families).

Figure 1.

Study Design. The effect of a personal history of hypertension in pregnancy was assessed by comparing event-free survival in women who had hypertension in pregnancy and their sister(s) who did not have hypertension in pregnancy. This within-family comparison was conducted by analyzing sibships as strata. The effect of a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy was examined by comparing event-free survival across families.

Results

Effect of a Personal History of Hypertension in Pregnancy

Characteristics of Women who had Hypertension in Pregnancy and their Sisters

Race, age, education, the proportion of women who had ever smoked, and the prevalence of hyperlipidemia did not differ between women who had hypertension in pregnancy and their sisters. Women who had hypertension in pregnancy had significantly greater body mass indexes (BMIs) and were more likely to have diabetes than their sisters who were either nulliparous or had normotensive pregnancies (Table 1). The present study only included genetically confirmed full siblings; yet sisters in 21% of families disagreed about their family history of hypertension. Women who had hypertension in pregnancy were more likely to report a family history of hypertension than their sisters who were nulliparous or had normotensive pregnancies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women who had hypertension in pregnancy and their sisters

| Characteristic | Women who had hypertension in pregnancy (n=252) | Sisters of women who had hypertension in pregnancy (n=353) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 0.94 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 63 (25%) | 91 (26%) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 102 (40%) | 145 (41%) | |

| Hispanic | 87 (35%) | 117 (33%) | |

| Age (years) | 56±11 | 56±11 | 0.88 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 34.4±7.0 | 32.5±7.0 | 0.001 |

| Education | 0.40 | ||

| Less than high school (≤8 years) | 53 (21%) | 82 (23%) | |

| Some high school (9–11 years) | 39 (15%) | 39 (11%) | |

| High school graduate/GED (12 years) | 71 (28%) | 97 (28%) | |

| Post high school (>12 years) | 89 (35%) | 135 (38%) | |

| Ever smoked | 60 (24%) | 95 (27%) | 0.39 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 159 (64%) | 223 (64%) | 0.98 |

| Diabetes | 97 (38%) | 107 (30%) | 0.04 |

| Family history of hypertensiona | 211 (84%) | 270 (77%) | 0.03 |

| Family history of CHD | 140 (56%) | 181 (51%) | 0.30 |

| Family history of stroke | 92 (36%) | 117 (33%) | 0.39 |

| Family history of CHD/stroke | 180 (71%) | 235 (67%) | 0.21 |

| Parity (% nulliparous) | 0 (0%) | 42 (12%) | <0.001 |

Values are mean±SD, or n (% of total). Sisters of women who had hypertension in pregnancy were nulliparous or had normotensive pregnancies. CHD, coronary heart disease.

In 21.6% of the 208 families, women disagreed about whether they had a family history of hypertension.

Risk of Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease Events in Women who had Hypertension in Pregnancy and their Unaffected Sisters

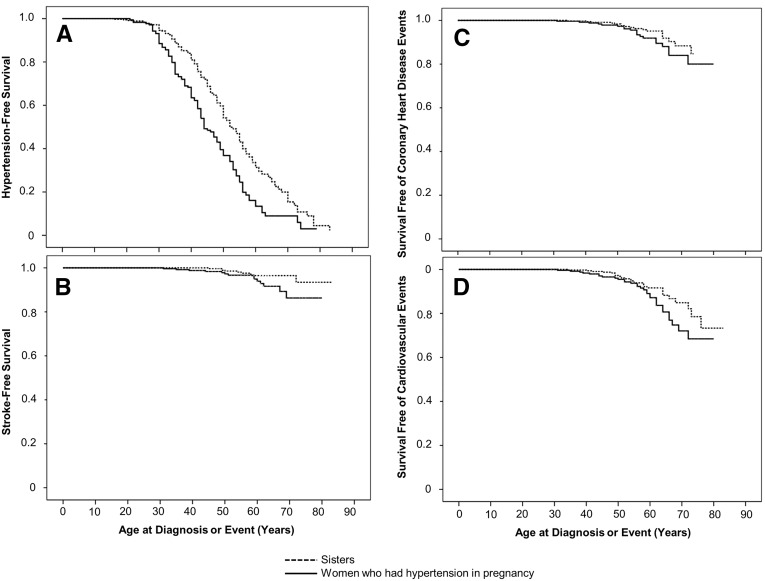

To examine the risk of hypertension that developed after pregnancy, we excluded 78 women who were first diagnosed with hypertension prior to or during the year of their first hypertensive pregnancy. Women who had hypertension in pregnancy developed hypertension at an earlier age than their unaffected sisters (median age 44 versus 52 years; P<0.001). Hypertension-free survival was lower among women who had hypertension in pregnancy than in their unaffected sisters (hazard ratio (HR) 1.72, 95% confidence interval (95% CI), 1.34–2.15, P<0.001, Figure 2A). This effect persisted after adjustment for BMI and diabetes (adjusted HR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.27–2.42, Table 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of a personal history of hypertension in pregnancy on event-free survival. Kaplan–Meier curves show survival free of hypertension (A), stroke (B), coronary heart disease events (C), and cardiovascular events (D; coronary heart disease event and/or stroke) in women who had hypertension in pregnancy (solid line) and their sisters who did not have hypertension in pregnancy (dashed line). Panel A excludes 78 women who developed hypertension prior to or during the year of their first hypertensive pregnancy and their sisters. All women are included in panels B–D.

Table 2.

Effect of a personal history of hypertension in pregnancy on disease risk compared with sisters with no personal history of hypertension in pregnancy

| Outcome | Women who had hypertension in pregnancy (n=252) | Sisters of women who had hypertension in pregnancy (n=353) | HRa (95% CI) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted prevalence | Adjusted prevalencea | Unadjusted prevalence | Adjusted prevalencea | |||

| Hypertensionb | 182 (72.3%) | 71.5% | 218 (61.9%) | 62.3% | 1.75 (1.27–2.42) | 0.001 |

| CHDc or stroke | 31 (12.4%) | 11.6% | 28 (7.9%) | 8.5% | 1.18 (0.64–2.16) | 0.60 |

| CHDc | 20 (8.0%) | 7.4% | 18 (5.1%) | 5.5% | 1.26 (0.60–2.64) | 0.54 |

| Stroke | 15 (6.0%) | 5.7% | 10 (2.8%) | 3.0% | 1.73 (0.66–4.53) | 0.27 |

Sisters of women who had hypertension in pregnancy were nulliparous or had normotensive pregnancies. Results were not different when nulliparous sisters were excluded (data not shown). CHD, coronary heart disease.

Adjusted for BMI and diabetes; sibships were analyzed as strata.

Seventy-eight women who were diagnosed with hypertension prior to or during the year of their first hypertensive pregnancy were excluded from the analysis.

CHD defined as myocardial infarction, angioplasty, bypass, stent, or balloon angioplasty.

Women who developed chronic hypertension before or during their first hypertensive pregnancy were included in analyses for coronary heart disease, stroke and the composite outcome of cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease and/or stroke). We observed trends toward a reduced stroke-free survival (HR, 2.28; 95% CI, 0.99–5.26, Figure 2B) and cardiovascular disease events (HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 0.96–2.68, P=0.07, Figure 2D) in women who had hypertension in pregnancy, compared with their sisters. Women who had hypertension in pregnancy developed stroke at a younger age than their sisters (mean age 77 versus 82 years, log-rank P=0.05). There was also a trend suggesting that women who had hypertension in pregnancy may have experienced cardiovascular disease events at a younger age than their sisters (mean age 74 versus 78 years, log-rank P=0.07). Unlike hypertension, these effects on the risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease events were no longer significant after adjustment for BMI and diabetes (Table 2). Survival free of coronary heart disease events was not significantly different in women who had hypertension in pregnancy, compared with their sisters (Figure 2C). Excluding nulliparous sisters had no effect on the conclusions for any outcome (data not shown).

Effect of a Sibling History of Hypertension in Pregnancy in Men and Women

Participant Characteristics

Race, education, the proportion of nulliparous women, and the prevalence of diabetes and hyperlipidemia did not differ between women whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy and women from families in which no sister had hypertension in pregnancy (Table 3). When compared with women from families in which no sister had hypertension in pregnancy, women whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy were significantly younger, had larger BMIs, and were less likely to have smoked and more likely to report a family history of hypertension. Race, education, BMI, the proportion of lifetime nonsmokers, and the prevalence of hyperlipidemia and diabetes did not differ between men whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy, and men from families in which no sister had hypertension in pregnancy. Compared with men from families in which no sister had hypertension in pregnancy, men whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy were younger and more likely to report a family history of hypertension.

Table 3.

Characteristics of siblings of women who had hypertension in pregnancy, and men and women from families in which no sister had hypertension in pregnancy

| Characteristic | Women whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy (n=353) | Women whose sister(s) did not have hypertension in pregnancy (n=1070) | P Value | Men whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy (n=235) | Men whose sister(s) did not have hypertension in pregnancy (n=684) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 0.21 | 0.25 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 91 (26%) | 326 (31%) | 79 (34%) | 258 (38%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 145 (41%) | 397 (37%) | 72 (31%) | 173 (25%) | ||

| Hispanic | 117 (33%) | 347 (32%) | 84 (36%) | 253 (37%) | ||

| Age (years) | 56±11 | 61±10 | <0.001 | 56±10 | 61±10 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.5±7.0 | 31.4±6.7 | 0.01 | 30.5±5.6 | 30.1±5.3 | 0.35 |

| Education | 0.37 | 0.40 | ||||

| Less than high school (≤8 years) | 82 (23%) | 274 (26%) | 69 (29%) | 213 (31%) | ||

| Some high school (9–11 years) | 39 (11%) | 117 (11%) | 38 (16%) | 81 (12%) | ||

| High school graduate/GED (12 years) | 97 (28%) | 323 (30%) | 54 (23%) | 167 (24%) | ||

| Post high school (>12 years) | 135 (38%) | 356 (33%) | 74 (31%) | 223 (33%) | ||

| Ever smoked | 95 (27%) | 357 (33%) | 0.02 | 164 (70%) | 469 (69%) | 0.75 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 223 (64%) | 718 (68%) | 0.16 | 142 (61%) | 442 (65%) | 0.26 |

| Diabetes | 107 (30%) | 345 (32%) | 0.50 | 65 (28%) | 230 (34%) | 0.09 |

| Family history of hypertension | 270 (77%) | 754 (70%) | 0.03 | 176 (75%) | 410 (60%) | <0.001 |

| Family history of CHD | 181 (51%) | 452 (42%) | 0.01 | 106 (45%) | 310 (45%) | 0.95 |

| Family history of stroke | 117 (33%) | 336 (31%) | 0.54 | 69 (29%) | 192 (28%) | 0.71 |

| Family history of CHD/stroke | 235 (67%) | 626 (59%) | 0.01 | 140 (60%) | 402 (58%) | 0.83 |

| Parity (% nulliparous) | 42 (12%) | 101 (9%) | 0.22 | NA | NA |

Values are mean±SD, or n (% of total). Women who had hypertension in pregnancy were not included in statistical comparisons. The first column includes all women who were nulliparous or had normotensive pregnancies, and came from a family in which at least one sister had hypertension in pregnancy. The second column includes all nulliparous and parous women from families in which no sister had hypertension in pregnancy. The fourth column includes all men from families in which at least one sister had hypertension in pregnancy. The fifth column includes all men from families in which there was at least one parous sister, and no sister had hypertension in pregnancy. CHD, coronary heart disease; GED, general educational development.

Risk of Hypertension and Cardiovascular Events in Men and Women whose Sister(s) had Hypertension in Pregnancy

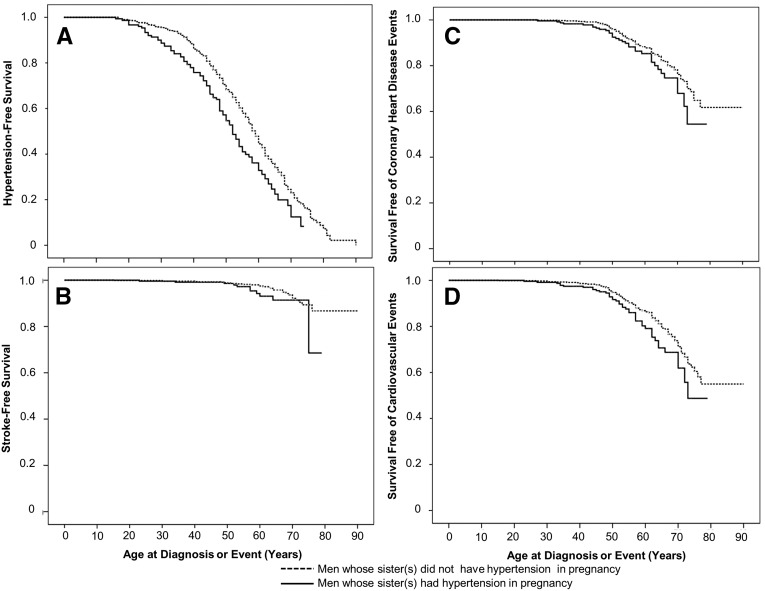

A sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy was associated with a shorter duration of hypertension-free survival in both women and men. Compared with women from families in which no sister had hypertension in pregnancy, women whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy were more likely to develop hypertension after adjustment for smoking, BMI, family history of hypertension and the number of parous sisters (adjusted HR 1.15, 95% CI, 1.04–1.26, Table 4). Results were not different when nulliparous women were excluded (data not shown). Men whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy were also more likely to develop hypertension (Figure 3A), and this effect persisted after adjustment for family history of hypertension and the number of parous sisters (adjusted HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.11–1.40, Table 5). A sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease events in men (Figure 3), but not in women. Compared with men from families in which no sister had hypertension in pregnancy, men whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy were more likely to experience cardiovascular disease events (adjusted HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.02–1.47, Table 5). There was also a trend toward an increased risk of coronary heart disease events in men whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy (adjusted HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.99–1.48). A sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy was not associated with differences in stroke-free survival in either men or women. Results of all models presented in Tables 4 and 5 were similar in a sensitivity analysis, in which all siblings in the family were considered to have a family history of the outcome if any sibling reported a maternal or paternal history.

Table 4.

Effect of a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy on disease risk in women who were nulliparous or had normotensive pregnancies

| Outcome | Women whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy (n=353) | Women whose sister(s) did not have hypertension in pregnancy (n=1070) | HRb (95% CI) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted prevalence | Adjusted prevalencea | Unadjusted prevalence | Adjusted prevalencea | |||

| Hypertensionc | 129 (62.9%) | 68.6% | 707 (66.1%) | 65.7% | 1.15 (1.04–1.26) | 0.01 |

| CHDd or stroke | 28 (7.9%) | 10.1% | 109 (10.2%) | 9.4% | 1.09 (0.88–1.35) | 0.44 |

| CHDd | 18 (5.1%) | 6.4% | 82 (7.7%) | 7.2% | 0.96 (0.76–1.30) | 0.96 |

| Stroke | 10 (2.8%) | 3.7% | 36 (3.4%) | 3.1% | 1.12 (0.77–1.63) | 0.56 |

Values are n/total (%). Specific inclusion criteria for each group of women are listed in the footnote to Table 3. Results were not different when nulliparous women were excluded, and when analyses were adjusted for intrafamilial correlation of outcomes (data not shown). CHD, coronary heart disease.

Adjusted for age, BMI, smoking, family history of the outcome and total number of parous full sisters in the family.

Adjusted for BMI, smoking, family history of the outcome and total number of parous full sisters in the family.

One hundred and forty-seven women whose sister(s) were diagnosed with hypertension prior to or during the year of their first hypertensive pregnancy were excluded from the analysis.

CHD defined as myocardial infarction, angioplasty, bypass, stent, or balloon angioplasty.

Figure 3.

Effect of a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy on event-free survival in men. Kaplan–Meier curves show survival free of hypertension (A), stroke (B), coronary heart disease events (C), and cardiovascular events (D; coronary heart disease event and/or stroke) in men from families in which at least one sister had hypertension in pregnancy (solid line) and families in which there was at least one parous sister and no sister had hypertension in pregnancy (dashed line).

Table 5.

Effect of a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy on disease risk in men

| Outcome | Men whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy (n=235) | Men whose sister(s) did not have hypertension in pregnancy (n=684) | HRb (95% CI) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted prevalence | Adjusted prevalencea | Unadjusted prevalence | Adjusted prevalencea | |||

| Hypertensionc | 92 (61.3%) | 67.1% | 444 (64.9%) | 63.7% | 1.24 (1.11–1.40) | <0.001 |

| CHDd or stroke | 43 (18.3%) | 21.6% | 126 (18.5%) | 17.3% | 1.22 (1.02–1.47) | 0.03 |

| CHDd | 35 (14.9%) | 17.7% | 107 (15.7%) | 14.7% | 1.21 (0.99–1.48) | 0.06 |

| Stroke | 11 (4.7%) | 5.9% | 31 (4.6%) | 4.1% | 1.34 (0.93–1.92) | 0.12 |

Values are n/total (%). Specific inclusion criteria for each group of men are listed in the footnote to Table 3. Results were not different when analyses were adjusted for intrafamilial correlation of outcomes (data not shown). CHD, coronary heart disease.

Adjusted for age, family history of the outcome and total number of parous full sisters in the family.

Adjusted for family history of the outcome and total number of parous full sisters in the family.

Eighty-one men whose sister(s) were diagnosed with hypertension prior to or during the year of their first hypertensive pregnancy were excluded from the analysis.

CHD defined as myocardial infarction, angioplasty, bypass, stent, or balloon angioplasty.

Discussion

This study examined the effects of a personal and sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy on the risk of hypertension, coronary heart disease and stroke among siblings from families with a high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. The results reveal several important findings. Women who had hypertension in pregnancy were more likely to develop hypertension later in life than their unaffected sisters. This is consistent with the hypothesis that nonfamilial factors, such as lasting damage caused by the hypertensive pregnancy, may contribute to the increased risk of future hypertension in women who have had hypertension in pregnancy. However, similar results could also be observed if women who had hypertension in pregnancy had a stronger genetic predisposition to hypertension or other risk factors, compared with their siblings who remained normotensive. The risk of hypertension was also increased among brothers and sisters of women who had hypertension in pregnancy; supporting the hypothesis that familial predisposition also likely contributes to the increased risk of hypertension in women who have had hypertension in pregnancy. Current guidelines identify a personal history of hypertension in pregnancy as a risk factor for future disease. The present study suggests that researchers should examine whether a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy may also identify men and women at increased risk for chronic diseases. The present study focused on families with strong family histories for hypertension or diabetes, and the contribution of familial factors may be higher in these individuals than among men and women from low-risk families. Population-based studies are needed to determine whether these results apply to the general population.

In contrast to hypertension, the risk of coronary heart disease events did not differ between women who had hypertension in pregnancy and their unaffected sisters after adjusting for BMI and diabetes. Larger studies are needed, as the absence of a significant effect may have been due to the small sample size and limited number of events. A sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy was a risk factor for cardiovascular disease events among men, but not among women who did not have hypertension in pregnancy. This apparent sex difference could be explained by lower statistical power in women, as women had fewer cardiovascular disease events than men (137 versus 169). Larger studies are needed to determine whether a sex difference is present. If confirmed, this sex difference could suggest that while a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy may provide information about future disease risk in men, a women’s own pregnancy history is more informative than that of her sisters when predicting future disease risk. We did not collect data regarding outcomes of the pregnancies that men had fathered; hence we were unable to examine paternal effects. However, the paternal contribution to hypertension in pregnancy is believed to be small. Data from the Swedish national registries suggest that the maternal genetic contribution to preeclampsia is 35%, whereas the couple contribution is 13%.14 The fetal contribution of 19% consists of relatively equal maternal and paternal components.14 A personal or sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy did not significantly affect the risk of stroke. This could also have been due to low power, as only 3.6% of women and 4.6% of men had experienced a stroke.

Epidemiology studies report that the increased risk of cardiovascular disease among women who have had preeclampsia and other forms of hypertension in pregnancy remains significant after adjusting for known confounders, including family history.5 However, this cross-sectional approach has significant limitations. Self-reported family history may be inaccurate. The present study only included genetically confirmed full siblings; yet sisters in 21% of families disagreed about their family history of hypertension. Our results suggest the potential for recall bias, as women who had hypertension in pregnancy were more likely to report a family history of hypertension than their unaffected sisters (Table 1). This effect appeared to be limited to hypertension, as women who had hypertension in pregnancy were not significantly more likely to report a family history of stroke or coronary heart disease. Finally, statistical models collapse complex family history information, including maternal and paternal history and the severity and age of onset of events, into a single dichotomous variable. If women who have had hypertension in pregnancy have a stronger family history, then cross-sectional studies would overestimate the effect of hypertension in pregnancy and underestimate the effect of family history. Sibling studies allow researchers to isolate the effect of a personal history of hypertension in pregnancy by comparing sisters who share the same family history.

Despite these advantages, sibling studies have rarely been used to investigate the mechanisms linking hypertension in pregnancy with future disease. A population-based Norwegian study suggested that the increased risk of end stage renal disease was due to renal damage caused by preeclampsia, rather than to familial factors.15 The risk of end stage renal disease was increased in women who had preeclampsia, but not in their brothers and sisters.15 Cardiovascular outcomes were not evaluated. A 1961 study reported that siblings of women who had preeclampsia had higher BPs at 30–50 years of age than siblings of women who did not have preeclampsia.16 However, brothers and sisters were pooled.16 The present study addresses several limitations of this previous study by assessing older individuals, including cardiovascular endpoints and examining men and women separately. Additional strengths include genetic confirmation of sibling relationships and the use of a racially and ethnically diverse cohort.

Limitations

All forms of hypertension in pregnancy were assessed together, as the sample size was too small to examine the effects of preeclampsia alone. However, for analyses of hypertension, we attempted to minimize the potential effects of chronic hypertension in pregnancy by excluding women who reported receiving a diagnosis of hypertension prior to or during the year of their first hypertensive pregnancy and their siblings. The study targeted sibships with a high prevalence of hypertension or diabetes; therefore the results may not apply to the general population. While clinicians and researchers use family history as a proxy for genetic predisposition, sisters share only 50% of their genome. Women who develop preeclampsia could have a stronger genetic predisposition to future disease, or other behavioral or environmental risk factors, compared with their sisters who have had normotensive pregnancies. However, the familial predisposition for future disease will still be more similar in sisters than in women who are not related. This cross-sectional study evaluated older men and women; hence survival bias may have affected the results. Pregnancy history, coronary heart disease events and stroke were determined by self-report. The pregnancy history questionnaire had a 80% sensitivity and 90% specificity for the determination of preeclampsia among women in Rochester, Minnesota.17 Population-based studies are needed to resolve these limitations.

Longitudinal studies with preconception measurements would be needed to identify conclusively the mechanisms underlying cardiovascular disease risk in women who have hypertension in pregnancy. However, these studies would be prohibitively expensive. They would require preconception cardiovascular risk assessments, very large sample sizes and long follow-up periods. In contrast, a sibling-based approach is feasible and can be completed quickly using existing data. The results provide insight into the general mechanisms underlying the future disease risk. They will also guide future research to identify specific mechanisms, and to develop interventions to prevent hypertension and cardiovascular disease.

Women who have had hypertension in pregnancy were more likely to develop hypertension later in life, compared with their sisters who had normotensive pregnancies. This study also identifies a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy as a novel familial risk factor for hypertension. In addition, a sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events among men, but not among women who did not have hypertension in pregnancy. These findings should be interpreted with caution, as this small study examined siblings from families with a high prevalence of hypertension or diabetes. Population-based studies are needed to determine whether similar effects are seen in the general population.

Concise Methods

Subjects

This analysis includes 919 men and 1477 women from 954 sibships who participated in GENOA,18 a multicenter study investigating the genetics of hypertension in white, black and Hispanic individuals. The sites enrolling black and white participants recruited sibships in which at least two siblings developed hypertension before age 60 years. The site that enrolled Hispanic individuals recruited sibships in which at least two siblings had diabetes to avoid potential confounding due to the high prevalence of diabetes among Mexican Americans. The protocol was approved by each site’s institutional review board. All subjects provided written informed consent before participating.

Full details of the design, participants, questionnaires and physical examination have been published previously.5,18,19 Detailed methods for the present study are available online (Supplemental material). This analysis focuses on phase 2, which included a validated pregnancy history questionnaire for women.17 All participants completed questionnaires regarding personal and family medical history. Height, weight, BP and fasting serum lipids were measured using standard protocols.

Definitions

Hypertension was defined as a self-reported physician diagnosis of hypertension and prescription antihypertensive medication use, or average BPs ≥140 mmHg systolic and/or ≥90 mmHg diastolic at the study examination. Coronary heart disease was defined as self-reported myocardial infarction, coronary angioplasty, coronary bypass surgery, balloon dilatation or stent placement. Cardiovascular disease was defined as a stroke or any coronary heart disease event. Stroke was determined by self-report. Hyperlipidemia was defined as one or more abnormal lipid measurements at the examination (total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dl, triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl, or HDL ≤40 mg/dl) or the use of lipid-lowering drugs. ‘Ever’ smoking was defined as a lifetime history of having smoked ≥100 cigarettes. Diabetes was defined as self-reported treatment with insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents, or a fasting serum glucose concentration of at least 126 mg/dl.

Women who reported experiencing hypertension in any pregnancy were classified as having had hypertension in pregnancy. Sibling relationships were confirmed by genetic testing. Only full siblings were considered when determining whether men and women had a sister who experienced hypertension in pregnancy. Unaffected sister(s) of women who had hypertension in pregnancy included all nulliparous women, or parous women who did not have hypertension in pregnancy, from families in which at least one sister had hypertension in pregnancy. Women whose sister(s) did not have hypertension in pregnancy included all women from sibships with at least two sisters (at least one of whom was parous), in which no woman had hypertension in pregnancy. Men whose sister(s) had hypertension in pregnancy included all men with at least one sister who had hypertension in pregnancy. Men whose sister(s) did not have hypertension in pregnancy included all men from sibships in which there was at least one parous sister, and no sister had hypertension in pregnancy.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SD or n (%). Unadjusted and adjusted prevalences for coronary heart disease events, stroke, cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease event or stroke) and hypertension are shown. Cox proportional hazard models were conducted with age as the time scale (see Online Methods). The effects of a personal and sibling history of hypertension in pregnancy on disease risk in men and women were determined using HRs presented with 95% CIs after adjusting for potential confounders. Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test were used to examine differences in event-free survival. Analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (21.0; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GENOA was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Institutes of Health (NIH) (U01-HL054481, U01-HL054471, U01-HL054512, and U01-HL054498).

This secondary analysis was supported by award number P-50 AG44170 (V.D. Garovic) from the National Institute on Aging.

T.L.W. was supported by the Office of Women’s Health Research (Building Interdisciplinary Careers in Women’s Health award K12-HD065987).

This publication was made possible by CTSA grant number UL1-TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the NIH.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit it for publication were solely the authors’ responsibilities.

This work has previously been published as an abstract (Reproductive Sciences, 21(3S):381A, 2014).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015010086/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Catalano PM, Williams MA, Wise PH, Bianchi DW, Saade G: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Scientific Vision Workshop on Pregnancy and Pregnancy Outcome. NICHD, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, Chireau MV, Fedder WN, Furie KL, Howard VJ, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Piña IL, Reeves MJ, Rexrode KM, Saposnik G, Singh V, Towfighi A, Vaccarino V, Walters MR, American Heart Association Stroke Council. Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Council on Clinical Cardiology. Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Council for High Blood Pressure Research : Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45: 1545–1588, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, Newby LK, Piña IL, Roger VL, Shaw LJ, Zhao D, Beckie TM, Bushnell C, D’Armiento J, Kris-Etherton PM, Fang J, Ganiats TG, Gomes AS, Gracia CR, Haan CK, Jackson EA, Judelson DR, Kelepouris E, Lavie CJ, Moore A, Nussmeier NA, Ofili E, Oparil S, Ouyang P, Pinn VW, Sherif K, Smith SC, Jr, Sopko G, Chandra-Strobos N, Urbina EM, Vaccarino V, Wenger NK, American Heart Association : Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women—2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 1404–1423, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy : Am J Obstet Gynecol 183: S1–S22, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garovic VD, Bailey KR, Boerwinkle E, Hunt SC, Weder AB, Curb D, Mosley TH, Jr, Wiste HJ, Turner ST: Hypertension in pregnancy as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease later in life. J Hypertens 28: 826–833, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Männistö T, Mendola P, Vääräsmäki M, Järvelin MR, Hartikainen AL, Pouta A, Suvanto E: Elevated blood pressure in pregnancy and subsequent chronic disease risk. Circulation 127: 681–690, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lykke JA, Langhoff-Roos J, Sibai BM, Funai EF, Triche EW, Paidas MJ: Hypertensive pregnancy disorders and subsequent cardiovascular morbidity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the mother. Hypertension 53: 944–951, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.North RA, McCowan LM, Dekker GA, Poston L, Chan EH, Stewart AW, Black MA, Taylor RS, Walker JJ, Baker PN, Kenny LC: Clinical risk prediction for pre-eclampsia in nulliparous women: development of model in international prospective cohort. BMJ 342: d1875, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melchiorre K, Sutherland GR, Watt-Coote I, Liberati M, Thilaganathan B: Severe myocardial impairment and chamber dysfunction in preterm preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy 31: 454–471, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamad RR, Eriksson MJ, Berg E, Larsson A, Bremme K: Impaired endothelial function and elevated levels of pentraxin 3 in early-onset preeclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 91: 50–56, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guimarães MF, Brandão AH, Rezende CA, Cabral AC, Brum AP, Leite HV, Capuruço CA: Assessment of endothelial function in pregnant women with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus by flow-mediated dilation of brachial artery. Arch Gynecol Obstet 290: 441–447, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambers JC, Fusi L, Malik IS, Haskard DO, De Swiet M, Kooner JS: Association of maternal endothelial dysfunction with preeclampsia. JAMA 285: 1607–1612, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melchiorre K, Sutherland GR, Liberati M, Thilaganathan B: Preeclampsia is associated with persistent postpartum cardiovascular impairment. Hypertension 58: 709–715, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cnattingius S, Reilly M, Pawitan Y, Lichtenstein P: Maternal and fetal genetic factors account for most of familial aggregation of preeclampsia: a population-based Swedish cohort study. Am J Med Genet A 130A: 365–371, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vikse BE, Irgens LM, Karumanchi SA, Thadhani R, Reisæter AV, Skjærven R: Familial factors in the association between preeclampsia and later ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1819–1826, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams EM, Finlayson A: Familial aspects of pre-eclampsia and hypertension in pregnancy. Lancet 2: 1375–1378, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diehl CL, Brost BC, Hogan MC, Elesber AA, Offord KP, Turner ST, Garovic VD: Preeclampsia as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease later in life: validation of a preeclampsia questionnaire. Am J Obstet Gynecol 198: e11–e13, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.FBPP Investigators : Multi-center genetic study of hypertension: The Family Blood Pressure Program (FBPP). Hypertension 39: 3–9, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weissgerber TL, Turner ST, Bailey KR, Mosley TH, Jr, Kardia SL, Wiste HJ, Miller VM, Kullo IJ, Garovic VD: Hypertension in pregnancy is a risk factor for peripheral arterial disease decades after pregnancy. Atherosclerosis 229: 212–216, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.