Abstract

Variants in the APOL1 gene are associated with kidney disease in blacks. We examined associations of APOL1 with incident albuminuria and kidney function decline among 3030 young adults with preserved GFR in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. eGFR by cystatin C (eGFRcys) and albumin-to-creatinine ratio were measured at scheduled examinations. Participants were white (n=1700), high-risk black (two APOL1 risk alleles, n=176), and low-risk black (zero/one risk allele, n=1154). Mean age was 35 years, mean eGFRcys was 107 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and 13.2% of blacks had two APOL1 alleles. The incidence rate per 1000 person-years (95% confidence interval) for albuminuria over 15 years was 15.6 (10.6–22.1) for high-risk blacks, 7.8 (6.4–9.4) for low-risk blacks, and 3.9 (3.1–4.8) for whites. Compared with whites, the odds ratio (95% confidence interval) for incident albuminuria was 5.71 (3.64–8.94) for high-risk blacks and 2.32 (1.73–3.13) for low-risk blacks. Adjustment for risk factors attenuated the difference between low-risk blacks and whites (odds ratio 1.21, 95% confidence interval 0.86–1.71). After adjustment, high-risk blacks had a 0.45% faster yearly eGFRcys decline over 9.3 years compared with whites. Low-risk blacks also had a faster yearly eGFRcys decline compared with whites, but this difference was attenuated after adjustment for risk factors and socioeconomic position. In conclusion, blacks with two APOL1 risk alleles had the highest risk for albuminuria and eGFRcys decline in young adulthood, whereas disparities between low-risk blacks and whites were related to differences in traditional risk factors.

Keywords: apol1, kidney function decline, albumin to creatinine ratio, socioeconomic position (SEP), APOL1, incident albuminuria

Progression from CKD to ESRD affects black Americans disproportionately.1,2 In addition, black persons in the United States experience faster rates of kidney function decline at early stages of disease, compared with white persons.3–5 The reasons for these observations remain unclear. Two variants in the gene encoding apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) (termed G1 and G2), which are common among individuals with African ancestry, but very rare in Caucasian persons, are linked to ESRD and CKD.6–10 The presence of two of these APOL1 variants was significantly associated with increased progression of CKD in studies that included black persons selected for established disease.11 In one recent report, the association of APOL1 with incident CKD in middle-aged black persons appeared to be weaker than that reported for advanced disease.12 The association of APOL1 variants with the incidence of albuminuria and trajectories of kidney function decline among young black persons with preserved eGFR in a population-based cohort has not been examined.

Furthermore, whether high-risk APOL1 variants explain previously observed black versus white differences in the risk of albuminuria and early kidney function loss is not well understood. In one recent study among persons with established CKD, black participants without APOL1 genetic variants remained at somewhat higher risk for disease progression, compared with white participants.11 The degree to which differences in traditional risk factors and lifetime socioeconomic position (SEP) may also play a role in explaining race differences in albuminuria and early kidney function decline among black persons with and without the APOL1 variants is not well established.

We have designed this study to evaluate the incidence of albuminuria and trajectories of kidney function decline among young black individuals with two APOL1 risk alleles (high-risk black), black persons with zero or one APOL1 variant (low-risk black) and white participants with preserved kidney function. We also sought to investigate the degree to which traditional kidney disease risk factors and markers of lifetime SEP may explain observed differences between the groups.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

The sample size for these analyses was 3030, after we excluded 81 black persons without adequate genotyping results, 29 persons with eGFR by cystatin C (eGFRcys) <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at baseline, and 37 persons with missing covariate data. Among these participants, mean age was 35±4 years at baseline (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study year 10). A total of 176 (13.2%) black participants had two APOL1 risk alleles (high-risk black). There were 424 black participants who had APOL1 genotyping but lacked samples at follow-up years 15 and 20 who were not included in the trajectories ancillary study. Of these, 47 (11%) had two high-risk alleles.

Overall, as previously reported, black participants were more likely to have lower incomes and lower levels of education. At baseline, high-risk black individuals had the highest prevalence of albuminuria (14%), followed by low-risk black individuals (6%), compared with white participants (3%). The eGFRcys at baseline was slightly higher for black compared with white participants (Table 1). There were no significant differences between high-risk and low-risk black participants in income, education, access to care indicators, body mass index (BMI), smoking, diabetes or BP levels at baseline (all P values >0.1) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of CARDIA participants by race and APOL1 status at baseline

| Characteristics | High-risk Black (n=176) | Low-risk Black (n=1154) | White (n=1700) | P Value Blacks Versus Whites | P Value High Versus Low-risk Blacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 34±4 | 35±4 | 36±3 | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Male | 79 (45%) | 503 (44%) | 817 (48%) | 0.06 | 0.75 |

| Income | <0.001 | 0.41 | |||

| <25k | 52 (30%) | 337 (29%) | 177 (10%) | ||

| 25k–49k | 74 (42%) | 460 (40%) | 543 (32%) | ||

| 50k-74k | 37 (21%) | 223 (19%) | 444 (26%) | ||

| ≥75k | 13 (7%) | 134 (12%) | 537 (32%) | ||

| Education | <0.001 | 0.65 | |||

| Less than HS | 8 (5%) | 73 (6%) | 38 (2%) | ||

| HS completed | 47 (27%) | 297 (26%) | 225 (13%) | ||

| College or more | 121 (69%) | 784 (68%) | 1438 (85%) | ||

| Wealth indicatora | 64 (39%) | 419 (39%) | 905 (55%) | <0.001 | 0.88 |

| Life hardship | <0.001 | 0.92 | |||

| Very hard/hard | 16 (9%) | 110 (10%) | 103 (6%) | ||

| Somewhat hard | 36 (20%) | 246 (21%) | 219 (13%) | ||

| Not hard | 124 (70%) | 792 (67%) | 1377 (81%) | ||

| Caretaker education | <0.001 | 0.85 | |||

| Less than HS | 33 (19%) | 221 (19%) | 153 (9%) | ||

| HS completed | 72 (41%) | 493 (43%) | 621 (37%) | ||

| College or more | 71 (40%) | 440 (38%) | 927 (55%) | ||

| Employment status | <0.001 | 0.04 | |||

| Employed | 139 (81%) | 970 (90%) | 1481 (88%) | ||

| Unemployed | 31 (18%) | 132 (12%) | 106 (6%) | ||

| Homemaker | 2 (1%) | 27 (2%) | 102 (6%) | ||

| Hardship obtaining regular care | <0.001 | 0.53 | |||

| Hard | 25 (14%) | 149 (13%) | 132 (8%) | ||

| Not hard | 151 (86%) | 992 (86%) | 1560 (92%) | ||

| Don’t know | 0 (0%) | 7 (0.6%) | 6 (0.3%) | ||

| Hardship paying for care | <0.001 | 0.56 | |||

| Hard | 44 (25%) | 311 (27%) | 339 (20%) | ||

| Not hard | 132 (75%) | 832 (72%) | 1356 (80%) | ||

| Don’t know | 0 (0%) | 5 (0.4%) | 3 (0.2%) | ||

| Smoking | 53 (30%) | 341 (30%) | 324 (19%) | <0.00 | 0.88 |

| Diabetes | 11 (6%) | 91 (8%) | 85 (5%) | 0.01 | 0.44 |

| Body mass index | 28.82±7.21 | 29.11±6.93 | 25.98±5.30 | 0.00 | 0.60 |

| Systolic BP | 113.81±14.70 | 112.61±13.30 | 107.31±11.16 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| Diastolic BP | 75.18±11.71 | 74.82±10.28 | 70.47±9.25 | <0.001 | 0.17 |

| eGFRcys ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 111±15 | 113±12 | 109±12 | <0.001 | 0.04 |

| ACR ≥30 mg/g | 22 (14%) | 57 (6%) | 41 (3%) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ACR mg/gb | 4.52 (31.5–10.66) | 3.95 (2.72–7.06) | 3.98 (2.79–6.11) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive use | 12 (7%) | 55 (5%) | 19 (1%) | <0.001 | 0.25 |

All values are mean±SD, except where otherwise noted. HS, high school.

Wealth indicator was measured by whether a participant reported owning a house or not.

Median (interquartile range).

Incidence of Albuminuria by APOL1 Risk Status and Race

For analyses of incident albuminuria, we additionally excluded 120 persons with an albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) ≥30 mg/g at year 10, as well as an additional 18 with missing genotyping or follow-up albuminuria information, for a total sample size of 2893. Albuminuria was measured at years 10, 15, 20, and 25 in CARDIA. A total of 233 persons developed incident albuminuria over the 15-year follow-up period. Approximately 78% of incident albuminuria cases among black participants occurred in the APOL1 low-risk group. The incidence rate in high-risk black individuals was 15.6 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 10.6–22.2) per 1000 person years, compared with 7.8 (6.4–9.4) for low-risk black, and 3.9 (3.1–4.8) for white individuals. The cumulative prevalence of albuminuria by year 25 (including persons with albuminuria at year 10) was 30% for high-risk black, 15% for low-risk black, and 8% for white persons.

Compared with low-risk black participants, the age and sex adjusted odds ratio (OR) for incident albuminuria was 2.46 (1.59–3.81) for high-risk black persons. Differences were not attenuated by adjustment for clinical characteristics or SEP (Table 2). When we compared low-risk black persons with one risk allele to those with zero, there were no differences in incident albuminuria (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.82–1.86, P=0.31).

Table 2.

Incident albuminuria by race and APOL1 risk genotype

| Group | N | Incidence Rate per 1000 PY | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |||||

| Comparison within blacks | |||||

| Low-risk black | 1090 | 7.8 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| High-risk black | 152 | 15.6 | 2.46a (1.59–3.81) | 2.93a (1.86–4.62) | 2.88a (1.81–4.59) |

| Comparison between whites and blacks | |||||

| White | 1651 | 3.9 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Low-risk black | 1090 | 7.8 | 2.32a (1.73–3.13) | 1.33 (0.96–1.84) | 1.21 (0.86–1.71) |

| High-risk black | 152 | 15.6 | 5.71a (3.64–8.94) | 3.89a (2.43–6.22) | 3.50a (2.14–5.71) |

Multivariate analyses include young black and white adults with no albuminuria at baseline. Model 1 incorporated demographic variables (age, sex), global ancestry; model 2 incorporated demographic and pathophysiologic variables (smoking, BMI, systolic BP, use of antihypertensive medications and diabetes); and model 3 incorporated demographic, pathophysiologic and socioeconomic variables (participant income, participant education, caretaker education, employment status and access to care indicators). PY, person years.

P values <0.05.

In comparison with white persons, high-risk black persons had a 5.7-fold increased odds of incident albuminuria, and associations were robust after full adjustment. Low-risk black persons had over 2-fold increased odds of incident albuminuria, compared with white participants. Accounting for clinical characteristics attenuated the differences, and these became nonstatistically significant. Further addition of SEP variables attenuated the estimates further, but there were no statistically significant differences between the models (P=0.27) (Table 2). The population attributable fraction, i.e., the increase in the incidence of albuminuria that can be explained by the APOL1 high-risk genotype among black persons, was 10.8% in fully adjusted models.

We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, we considered only persistent albuminuria, and findings were not materially different. For example, in adjusted models, OR (95% CI) were 3.44 (1.28–9.28) for high-risk and 1.60 (0.80–3.21) for low-risk black persons, compared with white individuals. Next, we evaluated the associations among persons with available data on participant wealth, and findings were not materially different. For example, in fully adjusted models, OR for incident albuminuria was 1.13 (95% CI, 0.79–1.61) for low-risk black compared with white persons.

eGFRcys Decline by Race and APOL1 Risk Status

The mean follow-up time was 8.92 years for high-risk black, 9.15 for low-risk black, and 9.48 for white participants in this study. The mean (SD) eGFRcys decline for the CARDIA population was 0.86% (95% CI, 0.81–0.91) ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year over the follow-up period. At 5 years of follow-up (CARDIA examination 15), the mean (SD) eGFRcys was 108±19 ml/min per 1.73 m2 among high-risk black persons, 110±14 for low-risk black, and 107±13 among white participants. At CARDIA examination 20, these were 101±18, 103±15, and 101±14 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively.

We estimated differences in eGFRcys decline between high and low-risk black persons, and each group to white persons, separately. Among black participants, high-risk APOL1 was associated with 0.38% ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year (95% CI, 0.13–0.63) faster eGFRcys decline compared with low-risk black persons. These differences were not attenuated after adjustment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in eGFRcys decline by race and APOL1 genotype

| Group | N | eGFRcys decline ml/min per 1.73 m2 (% per year) | β coefficient (95%CI) eGFRcys (% ml/min per 1.73m2 per year) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| Comparison within blacks | |||||

| Low-risk black | 1154 | 0.82 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| High-risk black | 176 | 1.19 | 0.38a (0.13–0.63) | 0.38a (0.14–0.62) | 0.40a (0.17–0.64) |

| Comparison between whites and blacks | |||||

| White | 1700 | 0.56 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Low-risk black | 1154 | 0.82 | 0.26a (0.14–0.38) | 0.10 (–0.01–0.22) | 0.04 (–0.08–0.16) |

| High-risk black | 176 | 1.19 | 0.64a (0.39–0.88) | 0.48a (0.24–0.72) | 0.45a (0.21–0.68) |

Model 1 incorporated demographic variables (age, sex, visit, global ancestry); model 2 incorporated demographic and pathophysiologic variables (smoking, BMI, systolic BP, use of antihypertensive medications, and diabetes); model 3 incorporated demographic, pathophysiologic and socioeconomic variables (participant income, participant education, caretaker education, employment status, access to care indicators).

The beta coefficients indicate the direction and magnitude of GFR decline: positive β coefficients can be interpreted as % ml/min per 1.73 m2 faster decline. For example, compared with low-risk black persons, high-risk black persons declined by 0.40% ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year faster. eGFRcys, estimated GFR by cystatin C.

P values <0.05.

Compared with white persons, high-risk black persons had 0.64% ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year (0.39–0.88) faster eGFRcys decline, and differences remained significant after adjustment. Low-risk black persons also had faster rates of eGFRcys decline compared with white persons, but adjustment for clinical risk factors attenuated the differences, and these became nonstatistically significant. The addition of SEP variables to the models including clinical risk factors further reduced differences between the groups (P<0.001 for added variables) (Table 3).

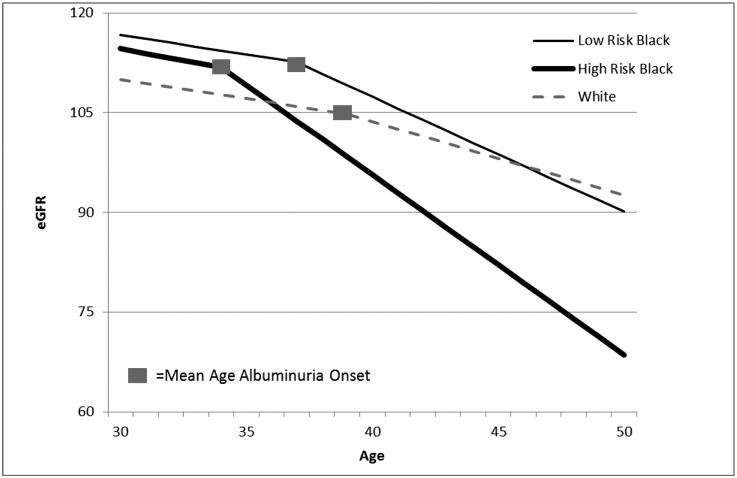

Finally, we were interested in comparing rates of eGFRcys decline accounting for the onset of albuminuria within each group (Figure 1). High-risk black persons had the earliest onset of albuminuria (mean age 34 years), compared with ages 37 for low-risk black and 39 for white individuals (P<0.01). Average eGFRcys decline among persons who had not yet developed albuminuria did not differ across groups. Specifically, in fully adjusted models, the average eGFRcys decline among high-risk black individuals was 0.68% (0.39–0.96) ml/min per 1.73 m2, compared with 0.59 (0.40–0.77) for low-risk black and 0.58 (0.40–0.76) for white persons. However, there were statistically significant accelerations in the rate of eGFRcys decline after the development of albuminuria within each group (Figure 1). After the development of albuminuria, the fastest adjusted rate of decline was observed among high-risk black persons, 2.71 (2.07–3.34) ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year, followed by low-risk black, 1.73 (1.32–2.14) and white persons, 1.11 (0.66–1.56).

Figure 1.

eGFRcys decline before and after onset of albuminuria by race and APOL1 status.

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort of young black and white adults with initially preserved kidney function, we found that 13.2% of black participants carried two APOL1 gene variants. These individuals were significantly more likely to manifest early signs of kidney disease, albuminuria and accelerated eGFRcys decline, compared with white participants and black persons without the APOL1 genotype. We also showed that black participants without the high-risk APOL1 genotype remained at higher risk for albuminuria and eGFRcys decline compared with white persons, and these racial differences were attenuated after adjustment for traditional risk factors. Taken together, our data fit a model in which the onset and progression of APOL1-associated kidney disease is characterized by albuminuria and reduced eGFR, in a manner similar to the onset and progression of diabetic nephropathy. Our findings also highlight that black persons without this genetic variant remain at higher risk for albuminuria and kidney function loss compared with white persons, and that these disparities were largely related to differences in traditional risk factors.

Our findings are consistent with prior reports showing the strong association of G1 and G2 APOL1 risk alleles with CKD, ESRD and progression of established disease in samples selected for kidney disease.7–10 In a prior community-based sample of middle-aged black persons (mean age 53 years), the presence of two APOL1 risk alleles was associated with prevalent albuminuria and incident CKD.12 Our study expands current knowledge and extends findings to a young, unselected, community-based population with preserved eGFR. Our finding that the rate of kidney function loss significantly accelerated after albuminuria onset among high-risk black persons suggests that albuminuria may be an early marker of disease, and that it can distinguish those persons with two APOL1 gene variants who are at the highest risk for kidney function loss. It is noteworthy that a recent report showed that, among persons with and without proteinuria, APOL1 high-risk variants still conferred an increased risk for CKD progression in persons with established disease.11 In contrast to these studies, our population is limited to young persons with preserved eGFR. Moreover, as ACR was not measured in the prior studies, whether some participants in those studies without elevated protein to creatinine ratios had low levels of albuminuria is not known. Our data also support the current models of HIV-associated nephropathy and FSGS, which suggest that the pathogenic role of APOL1 may involve disruption of podocyte7 and vascular architecture.13 Our findings that the eGFRcys slope did not significantly differ by APOL1 status prior to the onset of albuminuria among black persons suggest that the benefits of screening for APOL1 among young black adults with preserved eGFR should consider determination of albuminuria first to identify the persons at highest risk for kidney function loss, as screening for microalbuminuria may be cost effective in black populations.14 As the momentum for genetically informed medicine grows, further studies are required to determine the benefits of APOL1 determination coupled with periodic albuminuria screening among black persons.

Our observations that black persons without the APOL1 risk alleles remain at higher risk for albuminuria and kidney function loss compared with white individuals is also important, and consistent with a prior report.6 While high-risk APOL1 may explain about 10% of the excess incidence of albuminuria among black participants, incident albuminuria among low-risk black persons accounted for the highest proportion of albuminuria cases among black persons. We showed that race differences between low-risk black and white participants were mostly explained by adjustment for traditional risk factors such as obesity, smoking, diabetes and BP levels. Among these black persons without two APOL1 variants, research is necessary in order to determine whether kidney disease risk may be modifiable with current therapies.

To our knowledge, this is the first report evaluating the importance of genetic risk, traditional risk factors and SEP in explaining black-white differences in the development of albuminuria and eGFR loss in young adults with preserved kidney function. We were able to examine trajectories because we used cystatin C measured at the same laboratory, at the same time, from frozen samples. We were able to account for markers of SEP and BP levels throughout young adulthood. We must note several important limitations. We did not have direct measures of GFR. However, this is impractical in large epidemiologic studies. We could not investigate each individual’s eGFRcys trajectory. Rather, our analyses using repeated measures over time (up to three per individual) allow the trajectories to be interpretable as typical patterns for CARDIA participants. The eGFR and albuminuria data are available for just two follow-up visits 5 years apart, and the eGFR decline slopes are composites based on these values. We cannot specifically account for the exact temporal association of the development of albuminuria and the start of eGFR loss within each individual, as the data are insufficiently granular. We are unable to make inferences related to the importance of APOL1 in middle age or more advanced kidney disease. Future studies with larger sample sizes and availability of kidney biopsy tissue are required to elucidate pathologic mechanisms of APOL1-associated disease.

Black individuals with two APOL1 risk alleles had the highest risk for albuminuria and eGFRcys decline in young adulthood, compared with low-risk black and white persons. Disparities between low-risk black and with white persons were related to differences in traditional risk factors.

Concise Methods

Study Participants

We used data from 3030 participants in the kidney function trajectories ancillary study within the CARDIA study. We have previously described the development of this cohort, which was designed to examine factors associated with early kidney function loss among young black and white adults.5 Briefly, the parent CARDIA study was designed to study early determinants of cardiovascular disease. CARDIA recruited 5115 black and white persons age 18–30 years between 1985 and 1986 from four sites in the United States (Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; and Oakland, CA).15 Serum cystatin C and urinary albumin and creatinine were measured at years 10, 15 and 20 visits (corresponding to calendar years 1995–1996, 2000–2001 and 2005–2006), and an additional albuminuria measure is also available at CARDIA year 25. Persons who had a visit at year 10 or later (15 or 20) and with at least two consecutive cystatin C measures are included in the kidney function trajectories study.5 All participants gave informed consent, and the appropriate institutional review boards approved this study.

Measurement of Urinary Albumin and Kidney Function

Urinary albumin and creatinine were measured at years 10, 15, 20, and 25 and the urine ACR was expressed in mg/g. Kidney function was assessed by serum cystatin C. Cystatin C was measured at visits 10, 15 and 20 from frozen samples by nephelometer using the N Latex cystatin C kit (Dade Behring, now Siemens, Munich, Germany). All cystatin C measurements were performed simultaneously at the University of Minnesota and were calibrated for drift as previously described.5 We estimated the eGFR using the most recent CKD Epi cystatin C (eGFRcys) equation: eGFRcys=133*(min(cysC/0.8, 1)**(–0.499))*(max(cysC/0.8, 1)**(–1.328))*(0.996**age)*(0.932**if female).16 As previously described,5 we specifically chose to use cystatin C to estimate GFR trajectories in this population because it is less biased by race and because measures performed at the same time, in the same laboratory, from frozen samples, are better suited for estimation of trajectories.

Our main outcomes of interest were incident albuminuria and annualized changes in eGFRcys (in percentages). We defined incident albuminuria as having an ACR ≥30 mg/g at years 15, 20, or 25 among persons with ACR <30 mg/g at year 10. In a sensitivity analysis, we considered only persons with persistent albuminuria, in which persons who had one ACR ≥30 and a subsequent ACR <30 mg/g were coded as noncases.

Genotyping

In CARDIA, the APOL1 G1 and G2 variant alleles were genotyped in black participants using samples collected at year 0 by TaqMan assays (ABI, Foster City, CA). The G1 haplotype is defined by rs73885319, which is in near-absolute linkage disequilbrium (d'=1) with the second G1 allele rs60910145, and the G2 is a six base pair deletion (rs71785313). Based on the previously described recessive model for APOL1 and kidney disease, high-risk APOL1 genotype status was based on the carriage of two risk variants, which includes homozygosity at G1 or G2 or compound heterozygosity (G1/G2).7,11,12 Persons of European ancestry are known to have extremely low frequencies of these variants.17,18 Global ancestry was estimated using the software Eigenstrat.19

Covariates

Age, sex and race were ascertained by self-report using standardized questionnaires. At each visit, BP measurements were taken by trained staff using sphygmomanometry, and use of antihypertensive medication was recorded. Blood was collected at each study visit and stored at –70°C until measurements were performed. Diabetes was defined as fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL or use of insulin and/or oral hypoglycemic agents.

Lifetime SEP was evaluated by using several metrics previously shown to be associated with poor health in CARDIA.20 As a marker for childhood SEP, we used the highest level of parental education. As markers of adult SEP, we used participant income, employment status (working, unemployed, housemaker) and highest level of education by self-report up to year 10. Participants also reported whether they had a usual place for medical care, and the level of hardship in obtaining or paying for medical care (access to care). In sensitivity analyses, we also considered participant wealth, defined as whether the participant owned their home. Level of life hardship was obtained by self-report at CARDIA year 5. Wealth and lifetime hardship are included as sensitivity analyses due to missing observations or reported at earlier visits from baseline for this study.

Statistical Analyses

We first compared characteristics of high-risk black, low-risk black and white participants at baseline (CARDIA year 10). We then estimated the incidence of albuminuria over the 15-year follow-up period within each group. We evaluated differences between high-risk and low-risk black persons, and each group to white persons, using generalized estimating equation pooled logistic models. In order to investigate the importance of traditional risk factors and SEP in explaining observed differences, we built sequential models. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, global ancestry and study visit. Model 2 added smoking, BMI, and systolic BP and the use of antihypertensive medication as time-updated covariates, and diabetes. Model 3 added caretaker education, participant income and education, employment status and access to care (regular place for medical care and hardship paying for medical care). We evaluated differences between each subsequent model using the Wald test. We estimated the population attributable fraction for high-risk APOL1 on the incidence of albuminuria among black participants, using imputation-based causal inference methods.21 The population attributable fraction can be interpreted as the increase in the incidence of albuminuria that can be explained by the APOL1 high-risk genotype among black persons.

Next, we compared kidney function trajectories over 10 years among high-risk black, low-risk black and white persons. We have previously reported on methods for eGFRcys trajectory evaluation in CARDIA.5 For these analyses, we used log-transformed eGFRcys to reduce the influence of large changes at the high eGFR range observed in this population, and to reduce skewness.22,23 To estimate and compare overall annualized percentage changes in kidney function among the groups, we used linear mixed models with random intercepts and slopes to account for within-subject correlation of repeated measures. We present annualized percentage changes in eGFRcys, obtained by nonlinear back transformation of the regression coefficients. Models were adjusted sequentially as above.

Finally, we were interested in comparing kidney function trajectories before and after the onset of albuminuria among black persons with and without the APOL1 renal risk variants and whites, separately. Consistent with the reported peak onset age for APOL1-associated focal segmental sclerosis9 and with hypothesized mechanisms,7,13 we tested whether there was a significant acceleration in eGFRcys decline after the onset of albuminuria in each group. As above, we tested for differences in eGFRcys decline between groups, among persons who had not/had already developed albuminuria. For these analyses, albuminuria was considered as a time-dependent covariate, with time of onset imputed 2.5 years prior to the CARDIA visit at which albuminuria was first noted (midpoint of the interval since the previous visit). We used linear splines to model annualized percentage changes in eGFRcys, allowing for changes in slope at the imputed time of onset of albuminuria. All models were adjusted as above. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

C.P. is funded by grant 5R03-DK095877-03 from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and the Robert Wood Johnson Harold Amos Program.

K.B.D. was funded by R01-DK078124, P60006902 and K24-DK103992.

J.B.K. was supported by the NIDDK Intramural Research Program.

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under contract HHSN26120080001E.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201300025C and HHSN268201300026C), Northwestern University (HHSN268201300027C), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201300028C), Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201300029C), and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (HHSN268200900041C). CARDIA is also partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and an intra-agency agreement between NIA and NHLBI (AG0005). This manuscript has been reviewed by CARDIA for scientific content.

Dr. Peralta and Dr. Vittinghoff had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The sponsors did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu CY, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG: Racial differences in the progression from chronic renal insufficiency to end-stage renal disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2902–2907, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muntner P, Newsome B, Kramer H, Peralta CA, Kim Y, Jacobs DR, Jr, Kiefe CI, Lewis CE: Racial differences in the incidence of chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 101–107, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peralta CA, Katz R, DeBoer I, Ix J, Sarnak M, Kramer H, Siscovick D, Shea S, Szklo M, Shlipak M: Racial and ethnic differences in kidney function decline among persons without chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1327–1334, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peralta CA, Vittinghoff E, Bansal N, Jacobs D Jr, Muntner P, Kestenbaum B, Lewis C, Siscovick D, Kramer H, Shlipak M, Bibbins-Domingo K: Trajectories of kidney function decline in young black and white adults with preserved GFR: results from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases: The Official Journal of the National Kidney Foundation 62: 261–266, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DJ, Kozlitina J, Genovese G, Jog P, Pollak MR: Population-based risk assessment of APOL1 on renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2098–2105, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Langefeld CD, Oleksyk TK, Uscinski Knob AL, Bernhardy AJ, Hicks PJ, Nelson GW, Vanhollebeke B, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, Pays E, Pollak MR: Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 329: 841–845, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipkowitz MS, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Comeau ME, Bowden DW, Kao WH, Astor BC, Bottinger EP, Iyengar SK, Klotman PE, Freedman RG, Zhang W, Parekh RS, Choi MJ, Nelson GW, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, SK Investigators : Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with hypertension-attributed nephropathy and the rate of kidney function decline in African Americans. Kidney Int 83: 114–120, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, Johnson RC, Genovese G, An P, Friedman D, Briggs W, Dart R, Korbet S, Mokrzycki MH, Kimmel PL, Limou S, Ahuja TS, Berns JS, Fryc J, Simon EE, Smith MC, Trachtman H, Michel DM, Schelling JR, Vlahov D, Pollak M, Winkler CA: APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2129–2137, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tzur S, Rosset S, Shemer R, Yudkovsky G, Selig S, Tarekegn A, Bekele E, Bradman N, Wasser WG, Behar DM, Skorecki K: Missense mutations in the APOL1 gene are highly associated with end stage kidney disease risk previously attributed to the MYH9 gene. Hum Genet 128: 345–350, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, Astor BC, Li M, Hsu CY, Feldman HI, Parekh RS, Kusek JW, Greene TH, Fink JC, Anderson AH, Choi MJ, Wright JT, Jr, Lash JP, Freedman BI, Ojo A, Winkler CA, Raj DS, Kopp JB, He J, Jensvold NG, Tao K, Lipkowitz MS, Appel LJ, AASK Study Investigators. CRIC Study Investigators : APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 369: 2183–2196, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, Astor BC, Grams M, Franceschini N, Boerwinkle E, Parekh RS, Kao WH: APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1484–1491, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madhavan SM, O’Toole JF, Konieczkowski M, Ganesan S, Bruggeman LA, Sedor JR: APOL1 localization in normal kidney and nondiabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2119–2128, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoerger TJ, Wittenborn JS, Zhuo X, Pavkov ME, Burrows NR, Eggers P, Jordan R, Saydah S, Williams DE: Cost-effectiveness of screening for microalbuminuria among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 2035–2041, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR, Jr, Liu K, Savage PJ: CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol 41: 1105–1116, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Kusek JW, Manzi J, Van Lente F, Zhang YL, Coresh J, Levey AS, CKD-EPI Investigators : Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med 367: 20–29, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Seaghdha CM, Parekh RS, Hwang SJ, Li M, Köttgen A, Coresh J, Yang Q, Fox CS, Kao WH: The MYH9/APOL1 region and chronic kidney disease in European-Americans. Hum Mol Genet 20: 2450–2456, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Limou S, Nelson GW, Kopp JB, Winkler CA: APOL1 kidney risk alleles: population genetics and disease associations. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 21: 426–433, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D: Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet 2: e190, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudson DL, Puterman E, Bibbins-Domingo K, Matthews KA, Adler NE: Race, life course socioeconomic position, racial discrimination, depressive symptoms and self-rated health. Soc Sci Med 97: 7–14, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahern J, Hubbard A, Galea S: Estimating the effects of potential public health interventions on population disease burden: a step-by-step illustration of causal inference methods. Am J Epidemiol 169: 1140–1147, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perkins BA, Ficociello LH, Ostrander BE, Silva KH, Weinberg J, Warram JH, Krolewski AS: Microalbuminuria and the risk for early progressive renal function decline in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1353–1361, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu CY, Chertow GM, Curhan GC: Methodological issues in studying the epidemiology of mild to moderate chronic renal insufficiency. Kidney Int 61: 1567–1576, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]